THE BOY WHO WAS

PROLOGUE: THE FEAST OF CORPUS CHRISTI

HESE

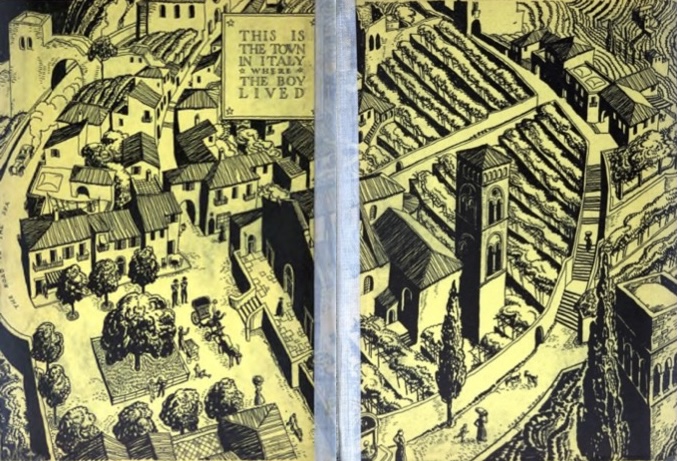

stories are about that part of Italy which sticks its tongue out at a little island in the blue-green sea. The island is Capri and the tongue is called the peninsula of Sorrento.

HESE

stories are about that part of Italy which sticks its tongue out at a little island in the blue-green sea. The island is Capri and the tongue is called the peninsula of Sorrento.

On the first Thursday after Trinity Sunday in the year of our Lord, 1927, the people of the peninsula were celebrating the Feast of Corpus Christi. Early on that morning an artist had gone climbing up to Ravello from the little town of Amalfi which sits like a bather on the shore of the Mediterranean dabbling her white feet in the transparent water. The path up which he climbed through the Valley of the Dragons was a staircase of stones. In the town the staircase was dark, for white, red-roofed houses rising one above the other leaned out over it as if they were trying to peer down the street. A baby giant, with one push, could tumble them all into the sea. Further on, the steps were cut in the solid rock, and on either side were vineyards staggering up the terraced slopes. Girls and women were working in the vineyards. Their red and orange kerchiefs twinkled over the lettuces and broccoli and beans and tomatoes and peppers and little green onions which were planted among the grape vines.

Lemon trees hung with pale yellow fruit and tiny waxen flowers grew in the sunny corners of the terraces. Cutting through their sleepy scent came the piercing sweetness of the blossoming grape. In the terrace walls grew maiden-hair fern and starry rock flowers and tufts of gray-green sage.

Far up the rocky gorge the staircase cut in the limestone reached a landing. This landing is really a flat place on the top of a high cliff, and on it long ago people had built a little town which today is called Ravello. In the center of the town square is an ancient fountain over which a winged lion and a winged bull stand on guard. The artist was thirsty after his long climb and he stopped for a drink from the lion's mouth.

The procession in honor of the Feast of Corpus Christi had just left the cathedral of San Pantaleone which had stood facing its own small platform-like square for over six hundred years. The priests and altar boys in their bright-colored vestments flowed down the narrow, high-walled streets like a mountain brook dyed with the green and red and blue and white of all the flowers which had ever bloomed on its banks. High above the crowds through which the procession made its way, the figure of the crucified Christ was lifted, and before and after came the altar boys in their long white gowns and tasseled shoulder capes and huge incongruous black boots, carrying tall flambeaux and banners.

The artist entered the church to examine the magnificent mosaic pulpit and the chapels which the Rufolos and the Frezzes and the La Marras and the other merchant princes of Ravello had built long ago for their salvation. But what his eye lit on first was a little scene which looked as if it might have fallen to the floor from one of the stained glass windows. An old woman, apple-cheeked, in a blue and white print dress covered with a voluminous white apron, and with a black shawl over her head and shoulders, was "making" the stations of the cross. At each station she knelt and a boy standing by her side read out the prayers from a little book. The boy was dressed in a goat-skin, and on his feet were sandals bound to his ankles with thongs of leather, an unusual sight in the crowd of townspeople gathered there. In the dim light of the church the artist could not be sure, but it seemed to him that the boy's skin was the color of honey, of the texture and tint that is sometimes found in old marbles which have lain a long time in the earth.

The artist followed the old woman and the boy when they left the church, and spoke to them as they stood on the terrace before the great bronze doors. The old woman started at the sound of his voice and the artist saw that she was blind.

"Pardon," said the artist to the boy, "will you allow me to make a picture of you?"

The boy gave him a charming smile and his black eyes twinkled. "But certainly, Signor," he said. "I am Nino. I live up in the mountains with my goats. If the Signor will wait while I guide old Lucia home, I will take him to my cabin. I must not leave my goats too long."

"I will wait," said the artist eagerly.

"Si, Signor," said the boy. He helped the old woman carefully down the steps of the terrace and guided her across the square with one hand under the crook of her elbow.

While he waited the artist idly examined the little bronze pictures set in the great doors. They had seen many things, those doors, since they were cast back in 1179, he thought.

A voice spoke at his elbow, "Yes, Signor, they have seen many things. Shall we go?"

The artist turned with a start. It was Nino. The boy looked, at that moment, as if he had played with the sirens and talked to the gods of Greece and Rome. He might be a little step-son of Pan, one of those half-gods, who once sat with mortals on their doorsteps and drank milk and ate bread and honey and talked celestial gossip of the gods on Olympus.

Nino piloted the artist through the streets. The black shirts of the Fascisti were everywhere adding shadows to the bright-hued festival crowds. On the street corners were the booths of the macaroni sellers, about which ragged street gamins loitered, and with the tail of their eyes on the black shirts, begged plaintively. "Mister, gimme a soldo for macaroni. Oh, I'm dying of hunger." It was fascinating to watch them eat the macaroni, quite worth the price of a soldo, thought the artist. With their fingers they picked up long sticky masses of it from the plates on which it was served, and swallowed them as neatly as a robin swallows a worm. Other groups hovered about the charcoal braziers from which the toasty smell of roasting chestnuts curled up to make the mouth water.

Little mouse-colored donkeys trotted along, piled high with fagots of wood from Scala, or with long narrow casks of wine, or wicker baskets. Here and there an itinerant street vendor carried a whole hardware store about with him. You could hear him coming half the town away. Pretty, soft-eyed girls bore casks of wine, or graceful earthenware amphorae of water on their heads. One child with her right hand held a basket with a baby in it on her head, and with her left, she led a little pig harnessed with a bit of string.

Firecrackers flung by shouting boys popped everywhere, under the hoofs of the patient donkeys, in the doorways of the fruit and bread shops, under the very feet of the passersby. The natives smiled their soft, wide-eyed smiles and shrugged when an indignant tourist became mixed up with a firecracker. It was a feast day, and why should the boys not make the noises and the smells they adored since they were doing it "to the glory of God."

The artist felt like a ripple slipping along in the wake of a dolphin, so smoothly did the goat boy clear a way for him through all the noise and confusion. Before long the town was left behind and the two were climbing a steep path over which a tangle of glossy-leaved myrtle and pale yellow coronilla hung. The broom was in flower and the bushes looked as if they were hung with clouds of tiny golden butterflies.

Suddenly the boy swung off from the main path. What they followed now was the merest ribbon of a trail through locust and chestnut trees. Sometimes the ribbon looped up over a boulder which blocked the way, or curled down into a little green dell where gay flowers–pink cyclamen and bluebells lit on slender stalks and tiny flame-colored gladioli and pink and red snapdragons–bloomed in the short wiry grass.

And now the path edged around a high cliff from which the artist could see the island of Capri kneeling like a two-humped camel in a desert of blue. Rounding the cliff the artist gasped with surprise. He had stepped out on a broad natural platform on which a small cottage stood. Ivy grew over the walls and the tiled roof was green with moss. From an enclosure at the back, penned in with a hedge of close-set brush, came the bleating and the stamping of goats.

"My little house," said Nino proudly. He led the way to the door and flung it open. The tall artist had to stoop to enter the doorway. It was rather dark inside after the glare of the sunlight on the sea, but he could see that it was very neat and clean. Pots of flowers were set in the windows and there were shelves all about the room covered with lace paper of various colors.

A shrine was set in the wall at the left. In this stood a little plaster Madonna with a rosy scalloped shell of holy water at her feet and a yellow palm branch over her head. She held her little boy in her arms.

Opposite the door was a huge fireplace and next to it a pipeless tile stove. Nino was very proud of this stove. He went to stand by it so that the Signor would notice it. The holes in the top were full of charcoal and over them hung copper pots suspended from a beam in the ceiling. Other things hung from the ceiling too–bunches of red peppers and garlic, strings of chestnuts and dried mushrooms, a whole ham, and wicker baskets of cheeses and bread.

A ladder led through a hole in the ceiling. "I sleep up there," said Nino, following the artist's glance. "Would you like to see my bedroom?"

"No," said the artist laughing. The ladder looked tottery to him and the hole in the ceiling very small. Then he saw some little carved wooden figures lying on the rough handmade table. "What are these?" he asked, picking up one and turning it over idly in his fingers.

Nino reddened. Without replying he asked, "May I pose for the Signor on the mountain. I must drive my goats to pasture now."

"Of course," said the artist. "I will help you."

"That is not necessary, Signor," said Nino smiling. He went to the door and whistled. A great black dog rose from the spot where he had been dozing in the sun. He yawned widely and then came trotting to his master's side. Nino went out and opened the pens. The goats came streaming past the doorway where the artist stood, led by a very old patriarch whose silky black beard was parted by the wind. The dog brought up the rear nipping at the heels of the laggards.

Nino ran into the cottage and caught up a wallet into which he thrust some bread and cheese. He hesitated and then swept in the little figures as well, looking at the artist slily as he did so to see if he had noticed. "Come Signor," he said.

The goats picked their way delicately over the narrow ledge of rock along the face of the cliff. Nino encouraged them and the artist as well by blowing a merry tune on his pipes. Beyond the cliff they struck into a path which led to the tip-top of Mount Cetara.

When they reached the bare poll of the mountain top, the man threw himself down on the warm rock. Nino sat composedly beside him and watched the goats wander off in search of the tender green shoots of sage brush.

In the bright sunlight the artist saw that without doubt the boy's skin was the color of honey. Now one kind of honey is clear pale yellow and that is clover honey. The other kind is a clear tawny yellow and that is buckwheat honey. This boy's skin was like buckwheat honey. He looked as if he had always been sitting there, and as if he would sit there forever and ever.

You remember those old witches who by one turn of the head could summon a storm, by another calm? Each turn of this boy's head was an enchantment too. When he turned his head the man turned his. He couldn't help it. Nino looked to the right and there was Naples by the fire-blue sea, held safe in the crook of one arm of the shore. He looked to the left and there was Salerno, held safe in the crook of the other arm of the shore. He looked behind and there were mountains and hills and valleys shutting off the wide world of which it is best not to know too much. Straight ahead, and thousands of feet below, were the islands, Capri and the Galli, flowers dropped from the mouth of the mainland. A good mainland it must have been in the old days to have been given the power to drop flowers from its mouth and not toads. These were the "Siren Isles" where the sirens, Parthenope and her sister, dwelt and sang to the men of the sea in the days when the world was young.

As Nino looked down the painter opened his sketch box. "Stay just as you are," he said. "You look as if you were listening to the sirens sing."

Nino smiled.

For half an hour he sketched. Then he threw down his pencil and stretched his arms over his head. "Aren't you tired?" he asked.

"No," said Nino, "but I'm hungry. I had only a piece of bread for breakfast. Will you share my lunch?”

"Yes," said the artist. "I'm hungry too."

Nino opened his wallet and drew out a loaf of black bread, a large piece of cheese and a flask of milk. As he did so, the little wooden figures fell sprawling from the open wallet to the ground.

"You must tell me what these are," said the artist pointing to the tumbled pile. "If it's a secret, I promise to keep it."

"Yes, I meant to tell you from the beginning," said Nino gravely. "You are an artist and you can help me. A silversmith's apprentice taught me how to carve wood and I made the figures, but I haven't any colors. I should like to have them colored," he said wistfully. He took out a sharp knife and carefully divided the bread and cheese into two equal parts.

"We'll have to drink out of the flask turn about," he said. "Do you mind?"

"No," said the artist, reaching for his share of the bread and cheese. "But what about the puppets?"

"You see, it's dull here now," said Nino. "Nothing much happens and I like to think about all the people who once made this coast an exciting place to be. So I carved their pictures in wood. Will you color them for me?"

"Yes," said the artist as he picked up the figures. "Let's make a pageant."

"Oh, yes," said Nino eagerly, "that's what I do. I'll help you. See, the sirens go first. They should have pale green faces and blue hair." He set the sirens on the rock above a little puddle of rainwater. "This can be the sea," said Nino, pointing to the water. He launched a little wooden ship on the sea. Peering over the bulwarks were several fierce-looking faces. "This is a ship of the Phoenicians," he said. "I have made a sail of scarlet cloth for it, but the sides should be painted and the men's faces should be brown." The little ship floated gaily on the water toward the siren rock.

"Odysseus comes next," said Nino. "His ship has a purple sail and Odysseus is tied to the mast so that the sirens cannot lure him into the sea with their songs. He must have black hair and a blue cloak."

"This must be the god of the sea," said the artist fishing up a puppet which held a trident in one hand and a conch shell in the other.

"Yes, that is Poseidon," said Nino. "He should be green all over except for a black beard and black hair. The Greeks called him the god of the dark locks. He comes next. We'll put him on the seashore." Poseidon was planted at the brink of the puddle.

"Who in the world is this?" asked the artist, holding up a rather lumpish-looking figure.

"Oh, that is Tiberius, the Roman emperor who lived on Capri. The people over there call him Timberio now and tell horrible tales of him. They say he used to throw prisoners over the cliffs and that the sailors stationed below beat the life out of any who were still breathing when they hit the rocks. But it isn't true. The Roman nobles hated Tiberius and made up all sorts of stories about him. He should have a purple toga to show that he was a Roman emperor." Nino set Tiberius on the rock overlooking the puddle and he really looked quite magnificent standing there with his arms folded.

"This is a little Jewish slave girl," said Nino, holding up. small figure. "She once lived in Pompeii." Nino looked at the figure lovingly. "Her shift must be green and her hair black, and see I have carved a little wreath of flowers in her hair." He looked at the Signor to see if he were laughing at him, but the artist's face was grave.

"And this is a Byzantine soldier," said Nino. "I hope you have some silver paint, for his armor must be all shiny." He looked at the artist anxiously.

"Oh, I imagine we can find some silver paint somewhere," said the artist. "Perhaps tin-foil will do. Who is this magnificent creature?" He held up a tall puppet with broad shoulders.

"He's a Goth," said Nino. "Isn't he splendid? He fought in the army of the Goths against the Byzantines. He must have a red tunic and his hair is yellow and his eyes blue."

"Here's another soldier," said the artist.

"Yes, that is Robert the Wise," said Nino. "He's a Norman, you know. When he and his brothers conquered this coast he was as full of tricks as a fox. He must have a yellow beard and a ruddy face. And these are Saracens." He picked up two fierce-looking puppets. "Saracens are brown." Nino lined up the soldiers as if they were on parade and set the Saracens behind them.

Then he picked up a small puppet gently. "This is a little boy crusader. His hair is to be buttercup yellow and his eyes periwinkle blue, and you must paint a red cross on his shoulder."

"I will," promised the artist.

"This is the Emperor Frederick the Second of the House of Hohenstaufen," said Nino. "He went on a crusade too, but he didn't like it in the Holy Land. When he came back he said, 'If God had seen my beautiful Sicily, He would not have chosen that beggarly Palestine for His Kingdom.' The Pope didn't like the Hohenstaufen. He called them a brood of vipers, and when Frederick died he sent the French to drive them out of the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily."

"You know your history, don't you?" said the artist.

"Yes," said Nino simply. "This is Charles of Anjou. He has a crown on his head. It must be gold and he must have purple clothes, for he is the French knight who drove out the Hohenstaufen and became King of Naples and Sicily. The people around here didn't like the French much. See, this is Lord John of Procida who loved the Hohenstaufen and plotted against the French. I have carved him in the dress of a monk, for he was always going about in disguise. The monk's frock should be gray."

"Who is the pirate with the long beard?" asked the artist as he set Lord John of Procida beside the Emperor Frederick whom he loved.

"Oh, that is Barbarossa, the Turk. You must make his beard very red. He was wicked; he tried to sack Amalfi."

"And these are bandits, I know," said the artist. "You have managed to make them look very fierce."

"Yes, they are bandits," said Nino. "They are to have red sashes and green breeches and black hats. I am carving one more figure now," he went on, taking out his knife and a piece of soft wood. "It is to be Garibaldi. He fought the French and Austrians near here, and helped to make Italy free."

The artist took out his paint-box. "I may as well start in," he said. "Shall I begin with the sirens?"

"Of course," said Nino, lifting his face from his carving. "It all began with the sirens."

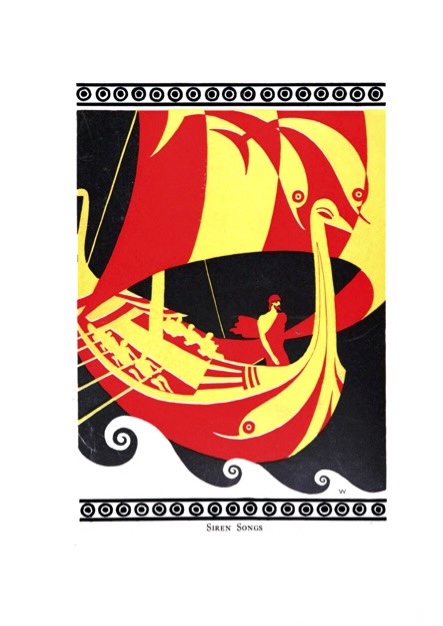

SIREN SONGS

SIREN SONGS

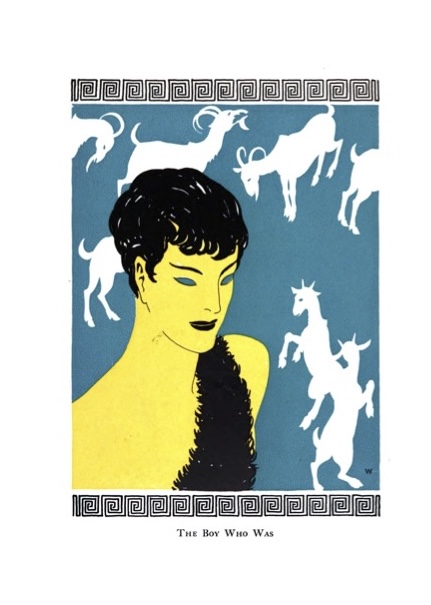

BOUT 3,000 years ago, more or less, a boy with black hair and black eyes and a face the color of buckwheat honey sat on a rock by the seashore. He had gathered together a little store of bright-colored pebbles and shells and was throwing them, one by one, out toward some islands clumped in the blue-green watery meadows of the sea.

BOUT 3,000 years ago, more or less, a boy with black hair and black eyes and a face the color of buckwheat honey sat on a rock by the seashore. He had gathered together a little store of bright-colored pebbles and shells and was throwing them, one by one, out toward some islands clumped in the blue-green watery meadows of the sea.

"Wake up, wake up, lazy one," he called as he threw the pebbles. "Wake up, Parthenope, and sing me a song."

A head lifted above the top of the island. The face of it was pale green. It was the sort of face of which one doesn't say, "the nose was thus and so, and the mouth was so and thus." It was the sort of face that is remembered but never talked about. The hair above it was blue. It was exactly the right color for the face.

"Ho, Parthenope," called the boy, "sing me a song."

"You are a bold boy," said the siren and rubbed her eyes as if she were only half awake. "What shall I sing about?" she called.

"Sing me a song about the ships that go where the sun drops over the edge of the sea. What do the brown men in the ships want at the end of the world?" The boy pointed to the West.

"The Phoenicians? Why, they go to find the gray stuff for their spear-heads. The people of the island where they buy it call it by a quick little name,"–she put a finger to her forehead–"tin."

"Sing about it," demanded the boy.

"Very well," said the siren, "but don't blame me for what happens."

The siren began to sing, and as she sang she combed her long blue hair with a comb of red coral. Had the boy been able to see her, he would have liked to watch the red sliding down through the blue, but when she sang he saw only the pictures of her song, moving across the sky like colored clouds at sunset.

SONG OF THE PHOENICIANS

A ship came beating up from where the sun rises and went sailing into the sea where the sun disappears. This was not so strange. Often and often the boy had seen other ships like this, with their carved sides and scarlet sails. Many and many a one he had watched until some interfering headland or mist of the sea had blotted it out of sight. How he had longed to be on one of those ships sailing into the unknown, monster-haunted land of the dying sun.

But this time the ship did not disappear. It sailed on and on. It passed between two rocky pillars out into a gray and angry sea. At last white cliffs rose up to meet it. The sailors on the boat deck pointed to the shore and brandished their weapons. The clash of cymbals floated out over the water. Close in to a curve of the shore swerved the ship and the sail came flapping down.

Now the boy saw a road, a long road dipping and rising like a white band over the dry turf of the chalkland. On the road were strange, blue-painted men with big moustaches who rode astride of shaggy little ponies. Some ponies were loaded with heavy lumpish-looking sacks.

The scene changed again to a cove where the ship lay drawn up on the beach. A band of the blue men came riding down to the shore. They unloaded their sacks and the brown men of the ship crowded around them, holding out rings and necklaces of orange metal. The blue men shook their heads. They sat their ponies and flung their spears into the air. The spears were fastened to their wrists with long straps and on each one a rattle was tied. When a man flung his spear and jerked it back by the strap the rattle made a fearful noise. The brown men flung down their trinkets and made a rush toward the sacks, but the blue men rode into the thick of them. The ponies stood stock still until their riders jumped off. Then the little fighting horses rushed at the brown men and knocked them sprawling on the seashore.

The Phoenicians picked themselves up and ran back to the ship. They returned with more gold which they threw down with fierce gestures. The blue men seemed to be satisfied at last. One by one they mounted their ponies and rode off, their arms and necks encircled with raw gold.

The men of the ship dumped the sacks into the hold. They filled painted jars with water from a reed-fringed stream, and then pushed the ship off into the sea. Now the ship was coming back, back toward the country of the rising sun. It wallowed deep in the water for its belly was full of rocks. On and on came the ship. Suddenly an island sprang up out of the sea in front of it. In the center was a meadow starred with flowers, but it was not the sight of the flowers that made the boy rise from the rock on which he was sitting and move like a sleep-walker toward the sea. It was the circle of cruel jagged rocks that ringed the lovely meadow. The high curved ship with its scarlet sail moved dreamlike toward the rocky island. Closer and closer it sailed. The lord of the ship must be asleep; the men must be asleep. Surely they could not see the jagged rocks below the flowery meadow, for the ship sailed head on toward the island. Closer, closer came the ship–

And then a scream rang out from the seashore: "The ship! the ship! It will dash its head against the island!" screamed the boy. By now he was knee-deep in the sea. On came the ship. "Stop! Stop!" shouted the boy, and now he was shoulder-deep in the waves.

A laugh came skipping over the water as a flat stone skips. It reached the boy and he stood still. A foolish grin spread over his face. The picture was gone; there was no ship. The pale green face of the siren clouded over with blue hair peeped over the top of the rock. "You asked me to sing," she said. "I told you not to blame me for anything that happened. You know that I always play tricks with my songs. But I always stop in time in the songs I sing for you. I must have someone to play with."

"Must you?" said a voice behind her.

Parthenope turned quickly. "Oh, it's you, sister," she said. The two sirens seen together were as like as two peas. And yet the face of Parthenope's sister seemed different. It was more cruel, perhaps. At least it did not look as if its owner would play games with little boys.

"Sister," said the newcomer, "it is time to go to the meadow." The sirens disappeared from the top of the island. The boy waded in to shore and climbed up on a rock.

Lucky for him he was only a boy. Lucky for him it was all a game, a game played by a siren with blue hair and a boy with a face the color of buckwheat honey. Often and often the boy heard the sirens singing. Little whiffs of their songs drifted past his ears as he hunted for birds' nests in the rocks, or fished with his hands in the sea. But unless the song was for him, his very own song, he never tried to reach the pictures which the songs made.

From his perch on the rock, the boy saw a little wind sniffing over the water as if it were on the track of some strange sea-monster hurrying to cover in the grottoes of Capri. And then far in the distance he saw a ship. It was a real ship this time, for the sirens were silent. It rode high in the water and a purple sail caught the wind and forced it, willy nilly, to push the ship along. As it drew nearer the boy noticed the curved beaks of the sea birds which finished off the lofty stern and the lofty prow.

Suddenly the wind ceased. That mighty huntsman, the lord of the wind, had cracked his whip and bade it go back to its kennel, Back it went, its tail between its legs, and the purple sail slacked down against the mast. Now there was a great scurrying about on the ship. It was plain to be seen that the chief of the crew was a king, or at the very least the son of a king. Tall and strong-limbed, with black hair that curled up like the tips of the hyacinth flower, he stood on the raised prow-deck and gave orders. Men leaped to the sail and drew it in and stowed it somewhere below. The calm violet of the sea about the ship was feathered white with the stroke of oar blades.

The chief, sitting in the prow was busy with a great circle of wax which he held between his knees. He cut it into small pieces with a bright sword and kneaded the bits of wax in his strong hands. Then starting with the men in the prow he passed through the length of the ship filling the ears of all the company with the soft wax. As for himself, two men bound him to the mast.

And now the ship was close to the shore, so close that the boy could shout to the man at the mast-head. He made a trumpet of his hands and called: "Who are you, O lord of the ship?" The sailors let their oars trail in the water and leaned over the bulwarks to see who it was who had hailed their chief.

The man at the mast-head called back, "I am Odysseus, son of Laertes, of the seed of Zeus, homeward bound from the Trojan war."

"Ho, Odysseus, why do you fill the ears of your men with wax?"

"That they may not hear the songs of the sirens."

"And why, O lord of the ship, do you let yourself be bound to the mast like an unruly slave?"

"That I may hear the song of the sirens and live. For I am told that the sirens with their songs lure seafarers out of their ships into the sea, and that the meadow where they sit singing is piled high with the bones of drowned men."

"Ho, I'm not afraid of the sirens," jeered the boy.

Odysseus did not answer this taunt. He made a sign to the rowers and once more the oar blades were dipped down into the sea. The ship leaped forward and rounded the Siren Isles. And then the sirens began to sing. Honey sweet was the song and although the boy could see the pictures that it made, it was not for him. No, it was for the king struggling with his cords at the mast.

SONG OF ODYSSEUS

HE first picture was that of a walled city set on a plain near the sea. The city was on fire. Smoke and flame pancaking out above the walls made patches of rosy light on the water. The harbor was crowded with ships, and on all of them men were raising anchors and setting the sails.

HE first picture was that of a walled city set on a plain near the sea. The city was on fire. Smoke and flame pancaking out above the walls made patches of rosy light on the water. The harbor was crowded with ships, and on all of them men were raising anchors and setting the sails.

The picture changed and the boy saw a fleet of twelve small ships struggling in a terrible tempest. The sky was covered with clouds and the sea was black. The ships were driven headlong and a mighty wind tore the sails to shreds.

After that the pictures followed one another swiftly. They were like scenes in a nightmare. In all of them moved the man who had named himself Odysseus. He and his men seemed always to be in trouble. In one picture they were sitting by a fire in a dark cave. And then a giant appeared at the entrance. He had only one eye set in the middle of his forehead. The red light of the fire made it glow like a live coal. The giant caught up two of the men in his great hands. He dashed them to the earth.

The fire died down and the cave was dark. When the flames shot up again the boy saw the giant sleeping on the floor of the cave. Odysseus was heating a wooden stake in the hot ashes of the fire. He drew it out and its sharp point glowed terribly. He and two other men seized the stake and poised it above the closed eye of the sleeping giant. The boy turned his head away. He could not bear to see what was about to happen.

When he looked up again he saw the blinded giant standing near the door of his cave. Below lay the sea and a ship was being rowed swiftly away from the shore. Odysseus stood in the prow shouting at the giant. Suddenly the giant reached out his hand and broke off the peak of a nearby hill. He flung it into the sea. The water heaved with the fall of the rock and almost swamped the ship.

In another picture twelve ships were moored in a harbor. Suddenly Odysseus and his men appeared, fleeing down the hill to the shore as if in terror of their lives. After them raced a host of giants. Odysseus sprang into his ship and cut the hawsers. His company rowed the ship hastily out of the harbor. But the other men were not so lucky. Before they could win through the harbor's mouth, the giants smashed their ships with rocks flung down from the cliffs above.

The scene changed again, and the boy saw a great hall hung with purple and cloth of gold. About the hall, on chairs like thrones, sat men eating and drinking. Then a woman entered. Her face was beautiful, but white and still, and her eyes were like twin gray stones. She waved a wand and the men wallowed down from the thrones. They had become swine. The woman drove them from the hall. Odysseus entered carrying in one hand a little milk-white flower, in the other a sharp sword. He sprang upon the witch woman, but she slipped away from him and fell to her knees.

All these pictures, and many more, were mirrored on the sky as the sirens sang. The pictures moved swiftly, much more swiftly than it takes to describe them, just as a nightmare happens more swiftly than one can possibly tell about it.

But at last the nightmare shadows vanished and the boy saw the sort of picture that one sees in a beautiful dream. On the sky was painted a meadow set in the heart of a little island. In the grass of the meadow lay the two sirens covered with garlands of rosy asphodel. Their faces were pale green and frosty like mint seen under running water. They held out their arms to the ship of Odysseus which was being rowed rapidly past their island. Floating out over the water came the words of a song:

"Come hither, king, and stay your barque,

The ocean's ways are strange and dark,

And strange and dark the way and long

From windy Troy to siren song.

And strange your home and dark the floor

Where murder sits beside the door.

And strange your son and dark your wife

With thoughts of death against your life.

We have no house to lay a guest,

But in our meadow you may rest.

We have no food that you may eat,

But O, our songs are honey sweet,

And lost to hunger, hurt and pain

Is he who listens to us twain.

Come hither, king, we know your story,

All your sorrow, all your glory.

All things we know, all death, all birth,

All that has been upon the earth.

Yea, and we know all things to be

On fruitful earth and barren sea.

Come hither, king, and stay your barque,

The ocean's ways are strange and dark,

And dark and strange the way and long

To Ithaca from siren song."

The song ended. The picture of the meadow faded from the sky, and the boy, looking out over the water was glad to see the ship of Odysseus dwindling to a tiny purple bubble in the distance. The sirens had failed. The face of Parthenope appeared above the circle of rocks which ringed her island. She was weeping.

"Ho, Parthenope," called the boy, "why are you crying?"

"I weep because we have failed, my sister and I. We have never failed before."

"You never fail with me," said the boy. "Sing me another song," he begged, "just a little one. I don't mind your tricks."

"Yes," said Parthenope, "I will sing you a song, my very last song. I promise not to trick you either. I shall give you a present instead. It has been fun playing with you. You are the only one I ever had to play with." She pushed her hair back from her face and began to sing. This time the song did not make pictures.

"All things I know, all death all birth,

All that has been upon the earth;

Yea and I know all things to be

On fruitful earth and barren sea.

"Who can make a boy's song

Of sunshine the day long,

Of pebbles and sea-shells,

Of butterflies and bluebells,

Of stories on the sea beach,

Of moon and stars out of reach?

Who can make a boy's song?

A boy can, the day long.

"I have heard a boy's song

Nearby, the day long,

Singing louder, singing bolder

As the little boy grew older.

Now I can no longer hold him

Close enough to tease and scold him,

So I ask the sea to love him

And the hills to watch above him.

"Let this boy forever be

Ward of hills and singing sea.

Let this boy, forever young,

Ancient warders be among.

Never let this boy grow old,

Feed his hunger, warm his cold,

Never grudge him salt and bread,

Never grudge him fire and bed.

"Let him watch the ships go by,

And cities rise and cities die,

And let his salt and let his bread

Wake visions of the storied dead.

All this I will to him who hears

A siren singing through her tears.

So take your song, my little brother,

Never shall you have another."

When the song ended the boy saw the other siren standing with her sister on the rocks. They were weeping in each other's arms. Then they turned and threw themselves into the sea.

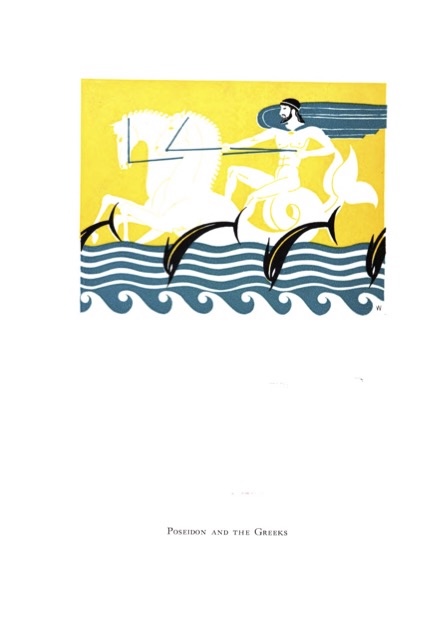

POSEIDON AND THE GREEKS

POSEIDON AND THE GREEKS

BOY stood on the last slope of a mountain leading down into a vast and flowery plain. About him milled a flock of lean-shanked goats. They moved their jaws listlessly as if they were chewing a meager and joyless cud.

BOY stood on the last slope of a mountain leading down into a vast and flowery plain. About him milled a flock of lean-shanked goats. They moved their jaws listlessly as if they were chewing a meager and joyless cud.

The boy shaded his eyes against the sun. It was early but already the air was glassy with the heat, and through it the grass down below and a river flowing slowly across the plain and the walls of a city in the distance looked blurred and wavy.

The goats lifted their heads suddenly and sniffed. They had winded the tender green herbage. O hé, down there was something worth setting the teeth to, something to make a cud worth chewing! The elders waggled their beards and stamped their feet. The boy drew a long two-reeded pipe from a pouch in his goat skin. He raised it to his lips but the goats seemed to think they had waited for permission too long. The first thin quaver of the pipe caught them half way down the slope and at the last they were knee-deep in the succulent grass.

The boy followed slowly. A fierce-looking dog kept at his heels. "Ho, Red-eyes," said the boy, "you'd think your little brothers of the mountain were after them."

The boy found a tiny brook flowing through the grass. It was no wider than his hand. He scooped up water to wash his face and drank with his mouth to the stream. From his pouch he drew a piece of black bread. Half of it he flung to the dog. Then with a sigh of content he leaned back against a rock and ate. About him the tiny forest of grass blades and flowers shook in the wake of hurrying green lizards. Grasshoppers and locusts filled the air with a thin monotonous humming. The boy nodded and half asleep fell over sideways into the grass.

He was awakened by the barking of the dog. He sat up and rubbed his eyes. At some little distance away he saw a strange young man fending off the furious dog with a long hunting spear. The young man saw the boy peering at him over the tall grass.

"Ho, boy," he called, "is this your wolf? Call him off, will you? Gods of Olympus, how he hates me!"

The boy called the dog. "Here, Red-eyes, here wolf-cub, down you! Come here." The dog came to him reluctantly turning at every step to bare his teeth at the young man who was now leaning on the spear. "Good dog," said the boy under his breath when the animal was near enough for him to touch. "Good dog, lie down."

The stranger came closer, paying no attention to the snarls of the dog. The boy saw that he was dressed in a short white linen tunic and on his feet were sandals bound to his ankles by leather thongs.

"What are you doing here, boy?" he asked sternly. "Don't you know that the pastures of Poseidonia are for the cattle of Poseidonia and not for a flock of half-starved mountain goats?" He waved his hand at the goats nibbling ecstatically at the lush sweet grass.

"It is because they are half starved that I brought them down," said the boy. "The pasture is dry and scarce on the mountains. What harm will it do to the cattle of Poseidonia to let them have their bellies' full for once? I mean to lead them back tonight."

"If they will go," murmured the young man. He was looking at the goats intently. "You have many black ones, I see."

"Yes," said the boy, "about half."

"If you drive your goats into the market-place, I'll warrant you a good price for the black ones," said the young man.

The boy stared at him. "They're half starved, as you said yourself, just now," he replied. "Who in the proud city of Poseidonia would give me a good price for a flock of thin-shanked goats?"

"Do you doubt my word, boy?" The stranger took a step forward. The dog lifted himself on his haunches and growled.

"No," said the boy. "Your word is good. I ask only the name of the customer."

"The customer," repeated the young man with. laugh. "Here," he tossed a gold coin to the boy. "That's your customer." The boy turned the coin over and over in his fingers. On the face was stamped an effigy of Poseidon, the gcd of the sea.

"You mean, Poseidon wants my goats?" asked the boy in an awestruck voice.

"He wants a sacrifice," said the young man impatiently. "All summer he has frowned on us. He has wrecked our fishing fleets in storms at sea. He has shaken the earth beneath the city walls. He has sent cloud-bursts to swamp our pasture lands and our fields of wheat and barley. Yesterday the men of Poseidonia gathered in the assembly place and appointed a sacrifice to appease the god. They sent me out to find the victims."

The boy turned the coin over. "But see," he said pointing to the picture of a bull stamped on the reverse, "the sacred animal of Poseidon is a black bull. Will the sacrifice of a parcel of half-starved goats appease him?"

"I don't know," said the young man with a shrug, "but we can try it. We have no cattle to spare for a sacrifice. Your people, the men of the mountains, drove them off in a raid this summer, except for a few cows and a bull that by good luck were grazing near the city walls."

"I have no people," said the boy.

An escaped slave, thought the young man, running his eyes over the slender stripling. "Well, you see how it is," he said aloud. "Our old men say that we cannot sacrifice our only bull to the god."

The boy looked troubled. "But I know Poseidon," he said. "He is not one to be cheated of his just and lawful due."

"We all know Poseidon," said the young man. "We have reason to know the heaviness of his hand. Well, at least we can try the goats. The smell of burning flesh is about the same, be it bull or goat," he said with a grin. "Perhaps the old one is shaking the earth somewhere else, and will never be able to tell the difference when he sniffs the sacrifice."

The earth rumbled. The boy looked up at the sky but it was clear and blue. He was troubled. But what could he do. He was on alien soil. The young men of the city could take his goats by force if he refused to part with them. He looked longingly at his beloved mountains. Under his breath he muttered, "Hail, Poseidon, god of the dark hair, this which I do, I do against my will."

"Well," said the young man impatiently.

"Take the goats," said the boy.

"But you must drive them," said the young man. "I am no goat-herd."

The boy and the dog ran among the goats cutting out the black ones and bunching them in one place. When the work was finished the boy whispered in the dog's ear. "On guard, Red-eyes."

"I am ready," he said to the young man. The dog looked wistfully after his master. But he could not follow. He must guard the remainder of the flock. The boy and the young man walked slowly across the plain driving the black goats before them. It was not easy to keep the hungry flock on the move for every grass blade and every flower was a sweet-scented invitation to dine. But the boy did it with the help of his pipe and his lusty shout and the flat of his hand smacked against truant shanks. The young man, now that he had won his point, shouted with laughter at the diabolic manoeuvers of the goats. Holding his sides, he headed them off when they stampeded in the wrong direction. Sweat poured from the honey-colored face of the goat boy. His black hair was matted in wet ringlets on his forehead. His black eyes snapped with anger.

"Never mind," said the young man, "you shall be well paid for this."

"I don't want your gold," muttered the boy.

"Poseidon will pay you then," said the young man teasingly. "He is one to pay his accounts, good for good, ill for ill."

"True," said the boy. Another rumble shook the earth. The young man did not seem to hear it. He was picking flowers–crimson snapdragons, and pale yellow mallows and lavender gilly flowers and pink and white asphodel and roses. He wove them into wreaths as he walked and when each one was finished he hung it around the neck of a goat. "Decked for sacrifice," he said, well pleased with himself. "We'll get old Xanthias, the goldsmith, to gild their horns and Poseidon, even if he looks on, cannot help but be satisfied."

The boy shook his head. They had almost reached the massive limestone walls of the city. The walls were very old and tufts of fern and acanthus grew in the masonry. "We will enter by the Golden Gate," said the young man. "It is nearest to the market-place."

At the gate they were halted by the guard. "Hail, Dion," cried the guard. "You have succeeded?"

"As you see," said the young man gaily, waving toward the goats. "Drive them to the market-place boy," he directed. "Straight down the street past the temple of Demeter. I go to find my father." The young man hurried off and the boy marshalled his goats into the narrow street. He had plenty of help. It seemed as if every boy in town had gathered during the short halt. Now they shooed the bewildered goats before them heading them off from the alleys which opened between the squat flat-roofed houses of sun-dried brick. The boy took time to look about him. It wasn't his fault if a gang of boys scattered his goats through the city. Let them answer to Dion if one was missing.

The houses lay close to the street line with narrow alleys between. Their white-washed walls were blank except for the street doors and a few slits in the upper stories to let in light and air. On the flat roofs the boy could see women and girls peering down from under their white veils at the mob of yelling boys and panic-stricken goats. A little way down the street the boy passed the temple of Demeter.

Coming from between the rows of white-washed secretive houses it was a relief to see the frank splendor of its pure and lovely colors and delicate tapering columns. Across the front stretched the sacrificial altar as long as the temple itself. The altar was piled high with barley and wheat ears and scarlet poppies in honor of Demeter, the goddess of the harvest.

And now the deep shouts of men underlay the shrill soprano of the boy's yells. The goats must have reached the market-place. The boy started to run. As he shot down the narrow street he ran full tilt into Dion and an old man who were just leaving a house door.

"Hold up, boy," said Dion catching him. "Where are the goats?" The boy shrugged. The goats it seemed were everywhere. They had been taken out of his hands. But from the shouting he thought they were in the market-place. "Well for you if they are," said Dion. The three hurried down the street. At the entrance to the spacious market-place it was evident that the goats were indeed there. The square was seething with them, and to each one clung at least three boys. The men had taken refuge on benches, behind statues or in the booths of the merchants. Some had even climbed trees. Dion roared with laughter. "Gods of the mountain, get them in order, boy," he commanded. The boy drew out his pipe and blew the goat call. At the familiar sound the goats rushed toward him. He was their master even if he had led them out of green pastures to this torment of noise and dust. Standing among his goats the boy's eyes filled with tears. "Hail, Poseidon, girdler of the earth," he whispered. "What I do, I do against my will."

Dion's father wrapped in a wine-red mantle had mounted the speaker's platform. "Men of Poseidonia," he began, "we have voted to sacrifice to our patron god, Poseidon the earth-shaker, for whom our city was named and who holds it under his special protection. That he is angry with us we have the proofs. And now, behold the sacrifice!" He pointed to the goats. "True, they are not the animals best pleasing to Poseidon but they are black, the chosen color of the god of the dark hair. They are without blemish, though somewhat thin. Let us gild their horns with gold that the god may be glad of our fair offering and let us conduct the sacrifice in the manner of our forefathers. So may the wrath of Poseidon be appeased."

"Hail, Poseidon, girdler of the earth, god of the dark hair," chanted the men and boys.

The old man left the platform and moved across the market-place to the street which ran south. After him crowded the men and boys. The men were wearing mantles of red and blue and purple and green which fluttered back now and then to show the white linen chitons beneath. The boys and youths were dressed in white tunics belted at the waist. There were hundreds in the company and they flooded the narrow street from house front to house front. Of women and girls there were none. Even the house roofs were empty.

Last of all came the boy driving the goats. Dion and an old man walked beside him. The old man wore a coarse gray woolen mantle with no chiton beneath. He carried a basket in which were anvil and hammer and pincers, tools of the goldsmith's trade.

Dion turned to the boy. "What is your name?" he asked.

"The men of the mountains call me Nino," said the boy.

"Nino, driver of the goats, son of no one, to Xanthias, the goldsmith, son of Nicanor and my father's slave," said Dion performing the introduction with ceremony. "Xanthias will gild the horns of the goats for the sacrifice," he explained.

"Who gives the gold?" asked Xanthias.

"The men of Poseidonia," said Dion proudly. "We may not have black bulls but we do not grudge our gold. And that reminds me. Here boy," he held out to Nino a little bag which clinked.

"No," said Nino drawing back. "I have said that I do not want gold."

"We'll give it to Poseidon, then," said Dion. He tossed the bag into the goldsmith's basket.

"Look, Nino," he went on, "we are passing the temple of Zeus." He pointed to the right at a temple much larger and more magnificent than that to Demeter. Facing the sea stood a gold and ivory statue of the king of the gods. All three raised their hands in salutation as they passed. "Hail aegis-bearing Zeus, the cloud-gatherer, hurler of the thunderbolt," they chanted.

Close to the temple opened the Gate of Justice. The men and boys had formed into a procession and were moving down through the gate to the seashore.

It was more difficult to keep the goats in order on the wide shore than in the narrow city street. Nino circled about them shouting and blowing on his pipe. He wished for Red-eyes. On the sea beach some of the boys formed a ring to pen in the goats. Others gathered driftwood and kindled several large fires.

Xanthias squatted on the sand and Dion's father heaped before him a pile of thin gold bars. The smith hammered out the soft gold on his anvil and skilfully gilded the horns of the goats. Then Dion stepped forward holding in one hand a beautifully carved basin of silver filled with water, in the other a basket of barley meal. Nearby stood other young men with axes ready to slaughter the goats.

Dion's father washed his hands in the basin. Then he tossed a handful of the meal into the air. This was the beginning of the sacrifice. A young man cut a lock of hair from the head of the finest goat and handed it to the old man who threw it in the fire. And then he began the prayer:

"Hear me Poseidon, girdler of the earth and grudge not the fulfillment of this request in answer to our prayer. To our city and to its sons give glory on the earth and recompense for this splendid sacrifice. Give increase to the cattle, the fruits, the grass, the vines and the plantations and bring them to a prosperous issue. Keep also in safety the shepherds and their flocks and give good health and vigor to us and to our households."

Now as the old man prayed, Nino saw, from the corner of his eye, a stranger standing close to the fire. He was tall and vigorous although he seemed to lean for support on a staff the point of which was buried in the sand. The front of his green mantle was covered almost to the waist by a long black beard.

"Poseidon comes himself to fulfill the prayer," murmured Nino. He was relieved, although now and then he heard faint rumbles in the earth.

After the prayer the young man slaughtered the goats and cut slices from the thighs. They wrapped the flesh in what little fat they could find and the old man poured red wine over the small bundles and burned them in the fire on a cleft stake. The men and boys stood near him holding in their hands five-pronged forks. When the sacrifice was consumed they cut the rest of the flesh up into small pieces and spitted and roasted it over the fires. Then they drew the meat from the forks and sat down and fell to feasting. There was plenty of wine in gaily painted earthenware bottles and gold cups from which to drink it.

No one paid especial attention to the stranger and Nino was puzzled until he remembered that the gods when they visit mortals take on the likeness of men known to the folk whom they honor. He himself would not have known him as Poseidon had he not seen that the staff was a trident and that in his beard tiny shells and bits of seaweed were entangled.

"They think him a fisherman," thought Nino.

It grew late. The sun went down and at the point where it fell into the sea a brilliant green spark flared up for an instant and went out. The sky directly above was downy with pink clouds, but about the horizon great black cumuli rolled up. Nino looked at them anxiously and even the crowd became uneasy. "Can it be," they muttered to each other, "that Poseidon is not appeased with the sacrifice?"

Nino felt a hand on his arm. "Come, boy," said Dion kindly. "You sleep in my house tonight. Red-eyes will guard your goats."

"No," said Nino, "I thank you, Dion, but I must go." His eyes followed the man with the black beard. He was steadily moving away from the crowd toward a headland overlooking the harbor. The men and boys straggled back to the city and entered the walls, some by the Gate of Justice to the south, others by the Gate of the Sea to the west.

"Farewell, O Nino, son of no one," said Dion.

"Farewell, O Dion, son of a chief," said Nino.

They raised their hands in salutation to each other. Then Dion followed his father to the Gate of Justice, and Nino hurried after the man in the green mantle.

On the headland the boy found the stranger. He approached cautiously. "Hail, Poseidon, shaker of the earth, god of the dark hair," he called softly.

The stranger turned. "Oh, it's you, boy," he said.

Nino walked to the edge of the headland and looked over. On the sea beach he saw a shell-incrusted chariot half in and half out of the water. Yoked to it were four golden-maned horses who were pawing the sand impatiently. The boy turned and faced the god.

"Poseidon, girdler of the earth, are you still angry with the men of Poseidonia?"

"I am still angry," said Poseidon.

"Did the sacrifice not please you? Do you demand their only bull to appease your wrath?"

"The sacrifice pleased me," said Poseidon. "Were it not for that–" He paused.

"O Poseidon, god of the dark hair, why are you still angry?"

"Sit down, boy," said Poseidon, "and do not be so formal. After all you are almost one of us. I will tell you why I am angry. You passed today through the city of Poseidonia. What temples did you see?"

"I saw the temple to Demeter, goddess of the harvest, and the temple to Zeus, the cloud-gatherer."

"Think boy, saw you no temple to Poseidon?"

"No, O god of the dark hair."

"That is why I am angry. The city was named for me. It bears on its coins my trident and my sacred animal, the bull, yet what have the people done to pay for my protection? For two hundred years I have been patient. When the first colonists from the city of Sybaris across the peninsula sailed up this coast I smoothed the sea for them. I tied my golden-maned sea-horses in their cavern stalls, and what happened? Lashing out with their brazen hoofs they kicked my new aquamarine chariot to bits.

"I sent a shoal of dolphins before the ships to guide the mariners to this flowery plain, well-watered, and lying betwixt indigo mountains and the violet sea. And what have they done to honor me except to sacrifice now and then?

I have kept a careful watch on them you may be sure, although I am very busy. I watched them build the temple to Zeus. That was right and proper for he is the king of gods and men. I watched them build the temple to Demeter. That was not so well, but I can understand that men who live by bread must honor the grain-giver.

"But I have watched in vain for the building of my temple. These people, I said to myself, are stupid. I will bring them to their senses. So I wrecked their fleets and flooded their fields and shook their walls. And they think I wanted a paltry sacrifice. Ho, ho. Yet for that sacrifice I will deal gently with them. Now harken, boy. You must be my messenger. Go to the house of Dion whose father is the chief of the city. Say to the chief that in a dream Poseidon revealed to you the true reason for his wrath. Tell him that Poseidon will not be appeased until his house stands in the city of Poseidonia. And this will be a sign that what you say is true. You will tell him that tonight Poseidon will smite the earth with his trident and the harbor and the guardian islands will sink into the sea."

The boy looked down at the deep wide mouth of the river and the fishing boats anchored in the shadow of the headlands. Beyond, a breakwater of islands held back the rush of the sea.

"Must you do this, god of the dark hair?" asked the boy.

"Boy, the men of Poseidonia may count themselves fortunate that I do not sink their city beneath the sea. Odysseus, son of Laertes, of the seed of Zeus who now wanders in the Elysian fields, could tell you what happens to those mortals who offend the earth-shaker."

The boy stood up, "I go, O Poseidon, god of the dark hair, girdler of the earth. Farewell."

"Farewell, O boy of the siren's song, ward of the sea and hills."

The boy went back to the city to the house of Dion. At first his story was not believed. But in the night the earth shook and the thunder rolled back and forth across the sky. In the morning the headlands above the harbor of Poseidonia had disappeared and the mouth of the river was choked with sand so that the water spread out over the fields. The little islands that broke the force of the sea were gone. The men of the city gathered on the seashore and wept.

Dion's father, the chief of the city raised his hand for silence. "Hear me, O Poseidon, the earth-shaker," he began, "and grudge not the fulfillment of this favor in answer to our prayer. Spare our city, in recompense for the splendid temple which this day the men of Poseidonia pledge to be a house and a resting place within the city walls for the god of the sea."

A low rumble answered the prayer. "He has heard," shouted the men and boys.

The chief of the city turned to Nino who had come to the seashore with Dion. "As for you, boy," he said kindly, "for your true prophecy I give you freedom of the city and leave to pasture your goats in the plains of Poseidonia for as long as you will." Nino was glad. Now he could watch the building of the temple while Red-eyes kept faithful guard over his flock.

That day the men of Poseidonia began work on the temple, and for many moons they labored in the quarries with horses and oxen and a thousand slaves. Of limestone formed by the deposits of water they built it and embedded in the stone were the tiny spiral shells and reeds dear to the heart of the sea god. They coated the stone with stucco and painted it green and blue and violet, the colors of the Tyrrhenian sea.

In the cella, the room of the god, they placed the statue of Poseidon, sitting in his chariot and holding in one hand his trident, in the other hand the great conch shell with which he summons the herds of the sea. They enclosed the colla with the peristyle, a range of columns where the god might walk in the cool of the evening. The cella had two entrances, one to the east and one to the west, so that the god might pass in either direction from his sanctuary through the sunny peristyle down to his chariot on the sea beach.

Poseidon when he came secretly to inspect his house after the ceremony of dedication was delighted with its arrangement. The boy watched him from behind one of the columns in the cella.

"Hail, O Poseidon, god of the dark hair, girdler of the earth," he called softly. "How do you like your house?"

"O, it is you, boy," said Poseidon. He touched a column with his trident. "It will last, boy," he said. "When the city of Poseidonia is forgotten and the men of Poseidonia are dust it will endure to be a house for the god of the sea."

THE ROMANS AND THE VOLCANO

THE ROMANS AND THE VOLCANO

T

was the night of the 23rd of August in the year of Rome 832. (79 A. D.). Titus, "the darling and delight of mankind," and the conqueror of

Jerusalem wore the purple toga which signified that he was emperor of the far-flung empire of Rome. In the city of Pompeii on the shore of the bay of Neapolis, Marcus Lucretius Publio was giving supper to two of his friends. The table was set in the triclinum, or dining-room, which opened into the peristyle, a spacious garden enclosed by colonnades. Soft wings of light from the oil-burning floor-lamps about the table fluttered over the chubby Cupids and Psyches painted on the walls. From the garden came the sound of water splashing in the fountains.

T

was the night of the 23rd of August in the year of Rome 832. (79 A. D.). Titus, "the darling and delight of mankind," and the conqueror of

Jerusalem wore the purple toga which signified that he was emperor of the far-flung empire of Rome. In the city of Pompeii on the shore of the bay of Neapolis, Marcus Lucretius Publio was giving supper to two of his friends. The table was set in the triclinum, or dining-room, which opened into the peristyle, a spacious garden enclosed by colonnades. Soft wings of light from the oil-burning floor-lamps about the table fluttered over the chubby Cupids and Psyches painted on the walls. From the garden came the sound of water splashing in the fountains.

The three men lying on couches about the table were talking earnestly. They seemed hardly to touch the food which barefooted slave girls running back and forth across the garden from the kitchen, presented to them.

"I don't like it," said Marcus, an oldish man whose bald head glistened above the wreath of roses which encircled his forehead. "It was like this sixteen years ago, and you know what happened then, Claudius?" He spoke to a man of about his own age reclining on a couch at his right. "Half the buildings in Pompeii were destroyed, and we're just now beginning to rebuild the temple of Jupiter in the forum."

"I know," said Claudius. "Rumblings in the earth and strange flashes of lightning out of a clear sky for days beforehand and then that frightful earthquake." He shuddered.

"It seems to me you are always having earthquakes around here," said a younger man with a shrug. "Why I've been here a week and the earth has rumbled three times. There was a small earthquake yesterday, but no one paid much attention to it. A statue fell down in the Forum and killed a slave, but what of it?"

"Therein lies the danger, Quintus," said Marcus. "The people are so used to slight shocks that they shrug their shoulders and, like you, ask, what of it? They think no more of it than a circus rider thinks of the bucking of his horse. They have forgotten the terrible earthquake of sixteen years ago which destroyed half the city. If I had my way I'd order the whole population to pack up and move before it is too late."

Quintus laughed. "You couldn't very well do that," he said. "Can you imagine what would happen if you stood at the door of the baths through which sooner or later everyone passes during the day, and warned each person to leave the city because at some time known only to the gods the earth will open and swallow Pompeii at one gulp? What, for example, would the owners of the vineyards on Mount Vesuvius say to you if you asked them to leave their vines just now when the grapes are beginning to ripen?"

"That's another thing," said Marcus. "Haven't you seen the little cloud that hovers over Vesuvius like a warning hand? Sometimes at night the underside drips red."

"Perhaps the mountain is a volcano," said Quintus lazily. "Old Vulcan, the blacksmith of the gods, may be tired of his furnace on Mount Etna and is setting one up here in Vesuvius."

A rumble like thunder came from the direction of the mountain. "There, what did I tell you?" he said gaily. "That was Vulcan hammering on his anvil.”

"Thunder on the left, out of clear sky," murmured Marcus. "A bad sign. Claudius, I've just thought of something. Tomorrow the priest of Jupiter takes the auspices to see whether the gods consent to the coming election. If it should happen that the liver of the sacrificial animal shows that some terrible event is soon to take place perhaps that will rouse the people."

"Well I hope that this time they choose an animal who will go willingly to the altar," said Claudius. "The last time they took the auspices the sacrificial pig turned tail and ran squealing through the crowd. The whole ceremony had to be postponed until the priests had trained a victim to walk gladly to the slaughter. It is too bad that the whole ceremony depends on the willingness of the victim. No one can tell what an animal will do.”

"True," said Marcus, "but there is reason in the custom. If the animal shows the smallest resistance it means, of course, that the sacrifice is not pleasing to the god. But have no fear, I myself have promised to supply the victim. He is the right age and color and very tame." He clapped his hands. "Ho, Miriam," he called.

A young girl came running across the court. She carried wreaths of roses and violets over her arm, for she thought that her master wanted fresh flowers for his guests. She wore a sleeveless green tunic and her legs and feet were bare. Her black curly hair was bound back with a twisted rope of laurel and rosemary. She tilted her sweet oval face inquiringly toward her master and held out the wreaths as if waiting for the order to crown the men with fresh flowers.

"Never mind the wreaths, Miriam," said Marcus, "where is Nick?"

"I locked him up master," said Miriam. "I was afraid that he might trip up the serving maids. He's always getting underfoot."

"Bring him here."

"Yes, master."

"That's a pretty girl, Marcus," said Quintus following her across the court with his eyes. "Where did you buy her?"

"She was one of the captives brought to Rome by Titus after the fall of Jerusalem nine years ago. I bought her and her mother when they were put on sale in the slave market after they had walked in chains in the triumph given to Titus. The mother died two years ago. I have had Miriam trained to arrange flowers. She does it very well." He waved his hand toward the centerpiece of maiden-hair fern and pale amethyst bell-like flowers arranged in a porcelain vase.

At that moment Miriam returned. A young goat walked at her heels with a dainty mincing step. He had the air of owning the world. His little budding horns and his hoofs were polished. His hair was smooth and very white. About his neck hung a wreath of roses and eglantine at which he nibbled tentatively.

Quintus murmured, "I didn't know a goat could be so clean."

The goat trotted toward Quintus who drew back from the edge of the couch.

"He smells the cakes," said Miriam.

"Give him one Quintus," said Marcus, "he won't bite you."

Quintus held out a little honey cake in the palm of his hand. The goat sniffed at it and then picked it up with his lips delicately without touching the outstretched hand.

"You see, Quintus, how tame he is," said Marcus. "He will go willingly to the slaughter, especially if the priest holds a sweet in his hand.”

"The slaughter!” cried Miriam, her black eyes opening wide.

"Yes, Miriam," said Marcus kindly. "Tomorrow the priest of Jupiter takes the auspices and I have promised to supply a willing victim."

"But master," said Miriam, "he is my goat. Nino gave him to me when he was only a tiny kid."

"Miriam," said Marcus, "a slave can have no possessions. But see, I am kind. Tomorrow I will give you gold enough to buy ten goats."

"I don't want ten goats," sobbed Miriam. "I want Nick." She fell on her knees and buried her face in the silk pillows on the couch of Marcus.

Claudius and Quintus raised their eyebrows.

"Yes," said Marcus, stroking her hair. "She is spoiled, but she is a good child. Miriam," he said turning up her face with a finger held under her chin, "I would not take your pet were it not necessary. Strange things are happening and the people must know what the gods devise. If there is danger they must be warned at once. We can take no chance of having the auspices delayed for lack of a willing victim."

Mariam looked at him steadily. "Master," she said, "your people are not my people and your god is not my god. Your people killed one million of my people. You destroyed my city and the temple of Jerusalem. You carried through the streets of Rome the trumpets and the table of the shewbread and the seven-branched golden candlestick that belong to Jehovah the lord of hosts. Behind the chariot wheels of Titus your people led the chosen people in chains and afterward sold them into slavery." She laughed wildly. "And now I must give my pet to be slaughtered for your people to appease your god.”

Marcus raised himself on the couch. "Miriam," he said, "you forget yourself. Go!"

Miriam ran sobbing across the court with the goat pattering at her heels.

"Will you order her flogged, Marcus?" asked Quintus reaching for a bunch of white grapes.

"No," said Marcus shortly.

On the morning of the 24th of August, before dawn, Miriam rose softly from the flat hard pallet spread on the floor of the tiny cell in which she slept. The cell had no window but its doorless entrance faced the narrow balcony overlooking the peristyle. The goat was sleeping in a bed of straw at her feet. But the slight noise she made in putting on her tunic wakened him. He wobbled to his feet with a faint bleat. Miriam put her hand gently on his muzzle. "Be still, Nick," she whispered. The goat munched the cake which she had held to his mouth.

Miriam poked her head out of the door and listened. All was silent except for the heavy breathing of the women slaves sleeping in the other cells along the balcony. In the darkness, Miriam tiptoed down the passage with her arm about the neck of the goat. She half carried him down the short flight of stairs into the peristyle. She glanced at the sky and saw that the stars were growing dim. She must hasten.

Groping her way along the tiled path she came at last to the atrium, the front room of the house. Here a wick was burning in a shallow silver dish filled with olive oil. The faint light flickered on the water in a pool sunk in the floor. Above the pool was a square opening for the rain to enter. Doorways opened on all sides of the atrium, but Miriam walked straight ahead, her bare feet making no sound on the mosaic pavement. The goat followed her obediently. Miriam prayed silently that no one would hear the patter of his hoofs. She left the atrium by a narrow hallway at the end of which a heavy oaken door opened on the street. Chained in the hallway was a great black dog. He was sleeping with his head between his paws. Miriam leaned over and patted his head. "It is Miriam, Niger," she whispered in his ear. The dog knew her voice. He lifted his head and opened his jaws in a wide yawn. Then he curled up and went back to sleep.

Miriam slipped back the well-oiled bolts of the door and stepped into the street. She stopped to let the goat trot ahead, then she turned and shut the door.

No one was astir in the chambers opening on the street which her master had rented to merchants and metal-workers. But as she walked down the raised sidewalk she heard a door bang. Dawn was not far off.

It was very hot and still. Not a breath of air stirred. Miriam crossed the street on high stepping stones which had been placed there for the use of foot passengers. The street was very narrow and paved with blocks of lava. The heavy produce carts and the chariots of the Romans had worn deep ruts in the pavement. On the blank house walls facing the street notices about the coming election were painted. Someone had scribbled "Sodoma, Gomora" on one of the walls.

Dawn came at last, a pink glow at the end of the street. House doors were flung open and slave girls with water jars on their shoulders gathered at the corner fountains, laughing and gossiping. Through the open door of a bakehouse came the smell of fresh-baked bread. It made Miriam hungry. But she hurried on swiftly. If she was questioned she meant to say that she was going to the mountains for wild flowers to decorate her master's house. She had done this often. The street slowly filled with a steady stream of traffic going in her direction. Farmers drove ox-carts piled high with lettuce, spinach, lentils, onions, garlic, oranges, lemons and black figs. Up from the sea came fishermen carrying great baskets of mullets, herrings and lobsters.

Slaves struggled along under the weight of baskets of bread, huge yellow cheeses, and casks of wine and olive oil. They were all making for the forum where the household slaves of Pompeii were sent to do the morning marketing.

At the entrance to the forum, slave gangs under the whip of their overseers were rebuilding the temple of Jupiter and their shouts and the clash of metal on metal and the clink of chisels on the stone helped swell the din. Miriam and her goat, passing between the temple and the meat market, crossed the forum to a small shop on the south side. She ran in at the open door. It was dark inside and the earthen floor felt damp to her bare feet. A strong smell of cheese scented the room. On a cask of olive oil near the door sat a wrinkled old woman.

"Rebecca," whispered Miriam catching her by the arm, "where is Peter?"

"Miriam," said the old woman peering up at her, "what are you doing here at this hour?"

"Oh, Rebecca," wailed Miriam, "where is Peter. Quick, tell me."

"It is not good for a slave to run away from these Romans," said the old woman, unmoved. "Better to wait till you can buy your freedom or have it willed to you by a kind master. You know Peter and I have saved to buy your freedom ever since our master's will set us free. Do you want to spoil everything by running away? You cannot escape you know. Romans, they have eyes everywhere."

"I don't want to escape," said Miriam. "I want to take Nick where he'll be safe. My master wants to sacrifice him to the king god of the Romans."

"Ai, ai, disobedience and running away," said the old woman. "It means the scourge as well as the branding iron."

"Rebecca, will you tell me where Peter is?" Miriam stamped her foot.

"He has gone down to the harbor," said Rebecca grudgingly. "If the sea looks calm he means to run down the coast toward Capreas to buy up goat cheeses."

Without a word Miriam turned and ran out of the door, the goat behind her. "If only I'm in time," she muttered. She dodged in and out of the crowd which filled the forum until she came to the temple of Apollo, the god of the sun. Turning down a side street which opened between the temple and the low court she came at last to the Gate of the Sea. It was a gate in name only, however, for the city wall facing the sea had been torn down to make room for more houses.

The sea was very calm. Not a ripple stirred its pale glassy surface. The orange-colored sails of the fishing boats far out at sea were stationary as if they had been painted on the sky. In the harbor mouth a forest of gaily colored masts sprouted from the fishing boats and pleasure galleys anchored there. Everything in sight seemed to be holding its breath as if it were waiting for something to happen. The cloud hovering above Vesuvius had grown larger and blacker and the under side was an ominous red.

Miriam wrung her hands. She did not know where to look for Peter's boat. And then she saw the man himself coming toward her. A blue woolen tunic reached from his shoulders to his knees. The lower part of his face was covered with a curly black beard. He was a huge ungainly man and he lumbered along like a water-logged ship.

Miriam ran toward him. "Oh, Peter," she cried, "are you going to Capreas? Will you take Nick and me?"

Peter stopped. He was a man of few words. "Yes," he said. "That is my boat yonder." He pointed to a small boat drawn up on the beach. "Wait for me there. I am going back for Rebecca."

"Rebecca!" said Miriam in astonishment. "But who will look after the shop?"

"The shop will look after itself," he said. "I don't like the look of things."

When Peter had gone Miriam lifted Nick over the gunwale of the boat and crawled in after him. She made a little tent of sailcloth and crouched under it with her arm about Nick's neck. After what seemed a long time she heard voices, the shrill scolding cackle of Rebecca's and the calm slow rumble of Peter's.

"You must be crazy," protested Rebecca, "leaving the shop like that to every impudent Roman boy who fancies a bit of cheese."

"Better to lose a few hundred-weight of cheese than our lives, Rebecca. I didn't live ten years on Sicilia under the shadow of Mount Etna for nothing. Now where is Miriam?"

"Here I am," said Miriam poking her head out from under the sailcloth.

"Hiding," snorted Rebecca. "She's running away, Peter. Ai, ai, nothing can save her now from the scourge and the branding iron."

"No one is going to think of runaway slaves for a long time in the city of Pompeii," said Peter with an anxious look at Mount Vesuvius.