1

All the Marvells except Heather were packing. She sat three-quarters of the way up the stairs and whoever went up or came down had to step over her.

"With the whole house to choose from," her mother said to her, "why do you have to settle down where you're in everybody's way?"

The Marvells were going to Virginia to visit the children's grandmother. They were leaving early the next morning and there was so much to be done still that Mrs. Marvell, who had been going up and down stairs all afternoon, was almost beside herself. Heather leaned against the wall, so her mother could get past. Later she had to lean again, when her mother came down, but she didn't give up an inch of room. Heather was eight, and the stairs was the place she came to when she had something on her mind.

There were only a few banks of snow left outside. The country was beginning to have a faint greenness. Two deer stepped across the road, fifty feet from the farmhouse. Roger Marvell looked out of the window and saw them go down into the deep woods. His heart stopped beating for a second, but he didn't say anything to the others about what he had seen. Roger was eleven and he wore long brown corduroy pants that whistled as he walked through the house gathering up his baseball glove, his parchesi set, his Chinese checkers, and the materials he needed for making model airplanes.

Tom and Tim were sitting on the floor in the parlor cutting pictures out of old Sears catalogues. Nobody expected them to do any packing. Tom and Tim were only five. When the telephone rang, two long and five short, Mrs. Marvell came in from the kitchen with an armful of shirts which she had just finished ironing and said, "Was that our ring?"

"It was the Hickathiers'," Tim said.

Mrs. Marvell put the shirts on a chair and took the receiver off the hook. She stood listening for a long time and finally she said, "I use brown sugar and a cup of raisins and a cup of sour cream . . . Yes . . . That's right, Mae . . . You're welcome, I'm sure." Then she put the receiver back on the hook, picked up the shirts, and said, "Heather dear, are your clothes in your little straw suitcase?" When Heather shook her head Mrs. Marvell said, "Well please get them ready. Don't let me have to speak to you again about it," and went on up to Roger's room.

"For pity sakes," she exclaimed. "You've filled your suitcase so full of toys there isn't room for anything else, Roger."

"But I need them all," Roger said.

"You need shirts and underwear too," Mrs. Marvell said, "and you certainly can get along without the World Almanac. Empty your suitcase out on the bed and let's start all over again."

The twins got tired of cutting out stoves and refrigerators, and ran off to play, but Heather lingered all by herself on the stairs, until a voice called her. It was her father's voice, the only one in the family that Heather always heard, no matter where her mind was.

"I was just going to," she said.

When she didn't move, Mr. Marvell said, coaxing, "We could feed the goslings together."

Heather got up reluctantly and came down the stairs.

"Papa, when I grow up," she said, "I want to come here and I want everything to be the way it is now. I don't want anything to change."

"I don't either," Mr. Marvell said. "Change is worse than a toothache. I don't even like the weather to change but it does, every day. Everything is bound to change, it seems like. Even you children. When you grow up you won't be a little girl any more and that's a big change."

"The more I change," Heather said thoughtfully, "the more I'm like me."

"Well," Mr. Marvell said, "when you come home, the house will be here where it is now, and the barn will be right across the road. The fields may have different things growing in them but they'll still be the same fields, and the trout stream will always be running through the marsh, so you'll know your way around, Heather, even if you've been away a long time. And besides, every once in a while a little change is a good thing, especially for people who don't like change." His arm rested on her shoulder for a moment and then he said, "Put your coat on and we'll go tend to your goslings."

After they had fed the goslings they paid a visit to the barn, then to the pump house, where Mr. Marvell let the gasoline engine run until water from the stream spilled over the top of the tank half way up the hill. Then they walked slowly across the lawn to the edge of the alfalfa field. Roger joined them there, and a few minutes later, Tom and Tim managed to slip outdoors when their mother wasn't looking.

It was almost dark. The trees were still bare, although it was the middle of April, and the frost was not entirely out of the ground. Down in the marsh one old bullfrog and a chorus of peepers announced the coming of spring. The children leaned against the horse-and-rider fence with their faces lifted to the sky.

Mr. Marvell lit his pipe and said, "It's not growing weather but it's a fine night for stars."

The farm was like a big house to him, with the sky for a roof. He was just as comfortable outdoors as he was in. He worked all day in the fields, like his neighbors, and he looked like the other farmers in the neighborhood when he stood around with them at church suppers, discussing the weather and the crops, but he was not like them. So far as the other farmers were concerned, there was only one good way of doing things and that was the way they had always been done, as far back as anybody could remember. Mr. Marvell was always discovering something new, always trying something out. He would read a book about how to raise vegetables chemically in water and before long one whole room in the basement would be full of glass tanks with hairy-rooted plants in them that produced big green leaves and eventually turned out to be beets or carrots or tomato vines. Or he would decide that he wanted to know more about cloud formations and would use words like cirro-cumulus and cumulo-nimbus and alto-stratus at the dinner table until Mrs. Marvell begged him to talk English. Recently he had become absorbed in the study of the stars, and on this night there were so many thousands of them that the children had trouble locating even the constellations they knew, like the Big Dipper and Cassiopeia's Chair. For a game they tried to find some star that their father didn't know the name of.

"What's that big red one?" Roger asked, pointing.

"That's Aldebaran, Roger. Aldebaran is part of the Bull, and the Bull is one of the constellations of the zodiac."

"That's Aldebaran, Roger. Aldebaran is part of the Bull, and the Bull is one of the constellations of the zodiac."

"What's a zodiac?" Tim asked.

"Heather," Mr. Marvell said, "tell Tim what the zodiac is."

"I don't think I really know," Heather said.

"I know," Roger said, "but I just can't say it."

"The zodiac is a beautiful broad region in the sky," Mr. Marvell said,

"a pathway that the sun travels in the daytime and the moon and the planets at night. The pathway is divided into twelve sections called the 'signs' of the zodiac, and each 'sign' has a cluster of stars in it. A long time ago shepherds minding their flocks at night and sailors standing the nightwatch on the deck of their ships began to notice that the heavens were filled with gods and heroes, huntsmen, ploughmen, and archers. The longer they looked at the sky, the more they discovered — birds, bears, farm animals and implements, every kind of monster you can think of. See the two stars that are the tips of the Bull's horns? And almost overhead is the Lion. Over there are the Twins."

"a pathway that the sun travels in the daytime and the moon and the planets at night. The pathway is divided into twelve sections called the 'signs' of the zodiac, and each 'sign' has a cluster of stars in it. A long time ago shepherds minding their flocks at night and sailors standing the nightwatch on the deck of their ships began to notice that the heavens were filled with gods and heroes, huntsmen, ploughmen, and archers. The longer they looked at the sky, the more they discovered — birds, bears, farm animals and implements, every kind of monster you can think of. See the two stars that are the tips of the Bull's horns? And almost overhead is the Lion. Over there are the Twins."

"What are their names?" Tom asked.

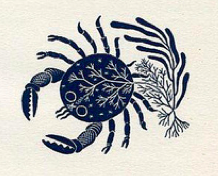

"Castor and Pollux," Mr. Marvell said. "And there's a crab, Roger, like the crab you caught when we were at the seashore."

"I remember," Tim said.

"You were too small," Heather said. "You were only a baby."

"I remember it," Tim insisted. "I remember it perfectly."

"He doesn't remember the crab Roger caught when he was only a baby, does he, Papa?"

"Why not?" Mr. Marvell said. "To people who lived in ancient times that cluster of stars to the east of it looked like a little girl. Virgo, it's called. The Bull, the Twins, the Crab, the Lion, and the Little Girl all lie in the pathway of the zodiac, and if you stayed up all night —"

"Mother won't let us," Heather said. "I've asked her to, lots of times."

"I know," Mr. Marvell said, "but if she did allow you to stay up all night tonight, you'd see more of the pathway. You'd see the Scales, and then the Scorpion, and then the Archer, and along about daylight you'd see the Goat. There are three more — the Water Carrier, the Fish, and the Ram — but you can't see them at this time of year. As the earth turns, the constellations of the zodiac rise and move westward across the sky and set. And every night of our lives they are a little west of where they were the night before at the same hour, so the sky is always changing with changing seasons."

"I think I see the Crab," Roger exclaimed.

"Where?" Heather demanded. "Where do you see any crab?" She couldn't bear to have Roger get ahead of her.

"Right there," he said, pointing.

"Yes," Mr. Marvell said. "That's the Crab all right. Big fellow, isn't he?"

"How big?" Tom asked. "Big as our barn?"

"Bigger," Mr. Marvell said.

"I see it," Heather said at last.

"And I see your mother coming," Mr. Marvell said.

In order to make the last suitcase close, Mrs. Marvell had had to sit down on the lid. Now, with a shawl over her head, she had come outdoors to be with the others. Mrs. Marvell had no luck with the stars. She couldn't even find the Big Dipper. Tom and Tim pointed it out to her, night after night, but she never had any idea where to look for it the next time. This didn't worry her because she could find a four-leaf clover whenever she wanted to. All she had to do was kneel down and run her fingers through the grass.

"Isn't it about time — " she began.

Roger, Heather, Tom and Tim groaned.

"Very well," Mrs. Marvell said, and let them hunt through the woods and fields of heaven a few minutes longer before she herded them indoors to bed.

The downstairs lights went out in the farmhouse, and shortly afterwards the lights upstairs, as Mrs. Marvell made her way from room to room, tucking the covers about her children and leaving them in darkness. Tom and Tim were already asleep and dreaming of refrigerators when she bent over them. She left the door of their room open so she could hear if they wakened and called to her in the night. She took Roger's book away from him and put an extra cover on the foot of Heather's bed and said, "Sleep well." She and her husband talked for a little while in their big old-fashioned walnut bed, and then they, too, abandoned whatever hopes and plans they had had for this April day and surrendered themselves to sleep.

In the barn the cattle slept in their stalls with their legs tucked under them, and the two work horses slept standing. The geese and the hens had long since found a place for the night, on roost or rafter, and the dog dozed in his house, with his head on his front paws and one eye open. Two miles away the lights of Briggsville began to go out. And then the lights in cities and towns, which to people in airplanes flying over them looked like circles and crosses and strings of beautiful colored jewels, also went out, leaving a large part of the earth's surface all dark and still.

The clock in the Marvells' kitchen went tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock, as the picture book of the stars shifted gradually from East to West, according to the great clock of the universe. The night winds blew, the air grew colder. The Bull, the Twins, the Crab, the Lion, and the Little Girl sank, each one in turn, below the horizon, and their places were taken by the Scales, the Scorpion, the Archer, and the Goat.

Then the Marvells' rooster stretched his neck and crowed, and the constellations faded slowly until the sky was once more a clear, empty, light blue.

When Mrs. Marvell got up and went downstairs to the kitchen, there was no crackling sound in the cookstove. She lifted a stove lid suspiciously and found the ashes of the fire from the night before. At the same moment Mr. Marvell walked into the barn and saw that the cows had not been milked.

August, the Marvells' hired man, was supposed to come up to the house the first thing every morning and build a fire in the cookstove. Then he usually went out to the barn, pitched down some hay for the horses, and started milking. August was a good man with animals and he could also do carpentry, but much of the time he was ailing. If it wasn't his sciatica it was his rheumatism, or his shoulder would be bothering him, or sometimes his knee. There was no telling what he was laid up with now. He lived on the other side of the marsh in a little shack he had built for himself and his wife. He had no telephone and the only way to reach him was to go after him. This morning there wasn't time before they left for the train.

Roger helped his father with the milking and Heather set the table for her mother. She remembered everything but salt and pepper, napkins, butter, and spoons. After breakfast the Marvells sat around with their hats and coats on and waited for August. The kitchen clock ticked louder and louder. Mr. Marvell took the railway tickets out of one pocket and put them for safekeeping back in another. Mrs. Marvell remembered about the kittens shut up in the woodshed and sent Roger out with a saucer of milk for them. In a moment he came running back.

"I see him," Roger cried. "It's August. He isn't sick after all. He's coming across the marsh."

Mr. Marvell went halfway down the hill to a place where he could look off between the limbs of the oak trees, and from there he saw a small figure plodding along through the dead grasses. He waved and the figure waved back. Mr. Marvell turned then and came up the hill, certain that August realized they were leaving, and would attend to everything.

But Mr. Marvell should have waited a little longer. The figure crossing the marsh reached a fork in the path, and, instead of coming straight on toward the Marvells' farm, turned right. It was not August, after all, but Jim Hickathier, who had been out since daybreak looking for a calf that had strayed.

By that time, though, the Marvells were piling into their station wagon. Mr. Marvell locked all four doors so none of the children could fall out, and then he put his foot on the starter. As the car drove off, Mrs. Marvell had a moment's uneasiness and looked back. She seldom left the place, even to drive in to town for groceries, without wondering if everything was all right and if the house would be there when she got back. This time it didn't occur to her that they might be leaving the house, the farm, and all the animals for three whole weeks without anybody to look after them.

2

When the Marvells got off the train in Virginia it was warm, the grass was bright green, and there was a haze of new leaves over all the trees.

Grandmother Marvell lived out in the country also, in a big white house with a lawn and two tall holly trees in front of it. There was a white fence around the lawn and beyond the fence were fields and pastures. The twins left their shoes and socks on the front doorstep and ran out into the pasture. Heather could not decide whether to pick violets or make a clover chain. In the end she went out to the apple orchard and climbed into a cloud of pink blossoms. Roger built a dam across the brook.

After supper the air was so still that Grandmother Marvell could walk across the lawn with a lighted candle in her hand. She unlatched the door of the smokehouse and held the candle high so the children could see the smoked hams hanging from the rafters, and the big slabs of bacon. When she blew the candle out they ran after lightning bugs and put them in a glass jar. Then they followed each other through the winding box hedges and played hide-and-go-seek round and round the house until they saw their father coming across the lawn with a telescope.

Each of the children had a corner of their grandmother's attic where his toys were kept. Year after year when they arrived in Virginia they could go up to the attic and find all their favorite playthings just where they had left them. There was also a corner full of games and toys that Mr. Marvell had played with when he was a boy, and the telescope belonged in that corner. The children had seen it there often when they went up to the attic for their own things, but this was the first chance they had ever had to use it. While the twins fought over the tripod, Mr. Marvell carried the telescope across the lawn and out into the pasture, where the whippoorwill was. In the pasture they could see the whole sky, but it was too early, and only a few faint stars were visible. Mr. Marvell set the telescope on its tripod and said, "While we're waiting for it to get dark, I'll tell you a story."

The children made themselves comfortable, Tom with his head in Heather's lap, and Tim and Roger leaning against their father. Then Mr. Marvell began:

"Once upon a time there was a man who borrowed a ladder from his next-door neighbor to clean his well. He stayed down the well a long time and when he came up he was very thoughtful. The next morning he went down again and stayed all day. 'What do you find to do down there all that time?' his wife asked him that night at supper. 'Oh I don't know exactly,' the man said. 'Lots of things.' 'You'll catch your death of cold,' his wife said. Actually what the man did when he reached the bottom of the well was to settle himself comfortably on one of the rungs of the ladder and look up. From the bottom of the well the sky was no longer light but a deep blue in which the stars shone faintly. He knew that in the wintertime he would find Orion over the parlor chimney at nine o'clock and over the kitchen chimney toward morning, but this was the first time he realized that there were stars in the sky in the daytime also. There was so much going on in the sky during the daytime that the man kept going back down the well, and that way he discovered that the sun's journey across the sky was never exactly the same. It was attended by one cluster of stars for a while, and then by another. He went down the well every day for months, and by the end of that time his wife was nearly frantic. She was sure he had discovered gold down there, or else that he was making a tunnel which would come out half a mile away on their neighbor's property and get them into trouble. She knew there was no use saying anything though, and so she waited until one day the man said, 'I'm going into town. I'll be back before dark.' No sooner had the front gate closed behind him than she slipped out behind the house and started to climb down the well. When she got to the bottom she saw that there was no gold and no tunnel, either — nothing except the moss-covered bricks her husband should have been cleaning all this time, and hadn't touched. While she was scrubbing away at the bricks with a wire brush, the neighbor came for his ladder because it was time to prune his apple trees. He looked around the place and nobody seemed to be home. He saw the end of the ladder sticking out of the well so he pulled it up. The woman had been standing with her feet braced on two stones. When she saw the ladder disappearing, she cried out, but the neighbor was deaf as a post and he balanced the ladder on his shoulder and went home with it. The woman's husband had gone to town to talk to the village schoolmaster about what he had seen down in the well. The schoolmaster said yes, there were stars in the sky in the daytime as well as at night, only people couldn't see them because the sunshine was so much brighter. Late that afternoon, just as it was beginning to get dark, the man came home with a large book the schoolmaster had given him. He opened the front door and called to his wife; no answer. He went out to the kitchen; she wasn't there and the stove had gone out. He went all through the house calling her name and there was still no answer. The man didn't know what to make of it. He had never come home and not found her there waiting for him. The house seemed very strange and empty without her. Along about bedtime he went outside for a last look at the sky and heard a sound no louder than a cricket. Somebody else might have thought it was a cricket, but he could tell his wife's voice anywhere, even down a well. He ran right away and got a rope and hauled her out. The poor woman's teeth were chattering so, she could hardly talk. She went to bed with five or six comforters and two hot water bottles and stayed there for a week trying to get warm. In the evening when the man had done the chores and cooked his own supper he would sit by his wife's bed and read to her from the schoolmaster's book. It was about the movements of stars and their names and about their influence on the earth, and especially about the constellations of the zodiac. The book said they were star clusters that look like people and animals. When the man came to this part, he put the book down and he said, 'But they are people and animals. I saw them. 'Saw who?' his wife asked, because she hadn't been listening very carefully. 'I saw all of the constellations of the zodiac — the Ram, the Bull, the Twins, the Crab, the Lion, the Little Girl, the

|

|

Scales, the Scorpion, the Archer, the Goat, the Water Carrier, and the Fish. I saw every last one of them, I give you my word.' 'Mercy!' said his wife, 'Where on earth did you see all this?' 'They weren't on earth, they were in the sky. I saw them when I went down the well.' 'Don't talk to me about wells,' the woman said, and so he went on reading. The book told how, thousands of years ago, certain men became so interested in the stars that they devoted their lives to the study. They were called astrologers and their neighbors never did anything without consulting them. When the moon was passing through the sign of the Goat, the astrologers told people to plant potatoes and radishes. When it was passing through the Water Carrier, the astrologers said for the farmers to go out and kill the mice and rats that were eating up the grain. When the moon was passing through the Fish, the astrologers advised everybody to plant flowers."

"Did it work out better that way?" Roger asked.

"The book seemed to think it did," Mr. Marvell said. "But that was a long time ago."

"How long?" Heather asked.

"I don't know how many thousand years," her father answered.

"Then the Little Girl must be quite an old woman by now," Heather said.

"The Little Girl is still a little girl, and the Twins are no bigger than Tom and Tim," Mr. Marvell said. "In the sky things must not be the way they are on earth. Some people believe that what a person is like depends on the position of the stars at the time of his birth. And maybe that's right. Who knows? Take Roger, for instance. Roger was born in December when the sun is going through Sagittarius, — that's another name for Archer. Well, Roger is a very good shot with a bow and arrow."

"Where was the sun when I was born?" Tim asked.

"Gemini," Mr. Marvell said. "That means the Twins."

"Do you hear, Tom?" Heather asked, poking her little brother gently. Then she turned to her father. "Do you suppose the zodiac people are like us?"

"I'd put it the other way round," Mr. Marvell said. "Do you think we could be anything like them?"

"What happened to that woman?" Roger asked. "Did she get over her cold?"

"After weeks and weeks," Mr. Marvell said. "And the first thing she did after she was up and around was to have the well filled with dirt clear to the top. Then she planted flowers in it.

"What kind of flowers?" Heather asked.

"Stars of Bethlehem," Mr. Marvell said. "By that time, though, her husband knew everything that was in the book, so it didn't matter that the well was full of dirt and he couldn't go down it any more to look at the constellations in the daytime."

It was quite dark now. Mr. Marvell got up and polished the lens of the telescope with his pocket handkerchief.

"The first person ever to watch the stars through a telescope," he said, "was a man named Galileo. He lived about three hundred years ago and he had a lot of new ideas. I wish I could of known him. Galileo's telescope was probably no larger than this one. He saw that the Milky Way was not a river, like everybody thought, but a cloud of little tiny stars. Now there are telescopes that are — why I saw a picture of one in the Milwaukee Journal that was bigger than our house at home, and astronomers can see millions of stars that Galileo never knew existed,"

Mr. Marvell bent down and peered through the telescope for several seconds. "Why!" he exclaimed finally. "That's the queerest thing I ever heard of!"

"What's the queerest thing you ever heard of?" the children asked.

"I can't find the Crab," Mr. Marvell said solemnly. "It just isn't there."

3

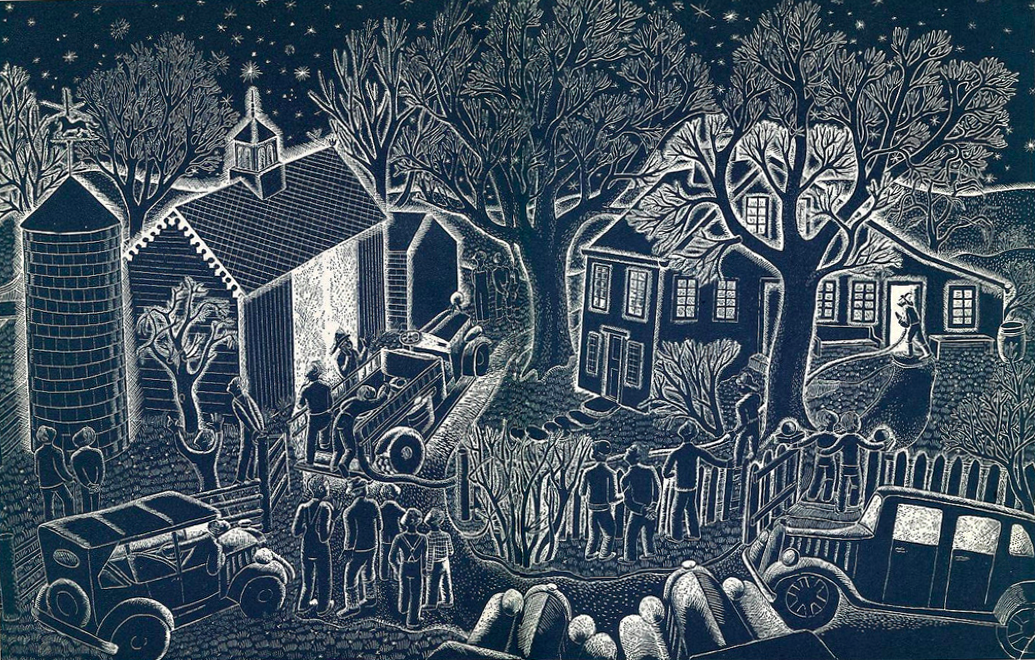

In Wisconsin that same night, Jim Hickathier was wakened by a light shining in at his bedroom window. It was so bright that he thought his barn was on fire. He jumped out of bed and rushed to the window. The barn was safe. Standing at the window, with his nightshirt flapping around his bare legs, he could see that the light, whatever it was, came from somewhere beyond the edge of his farm.

"Must be Marvells' place," he said to his wife, who was also awake by this time.

He drew his trousers on over his nightshirt, and went into the next room and woke up his son. Leaving the womenfolk wide awake and bewildered, the two of them clumped down the stairs and outside, where the Model T was parked under an oak tree. Jim sat at the steering wheel and young Jim, who was fifteen and very strong for his age, cranked. After ten minutes the engine turned over, wheezed, sputtered, and finally settled down to a steady cough. By that time young Jim had taken off his sweater and coat and was perspiring freely.

His grandmother, with her white hair in two braids, leaned out of an upstairs window and said "Boy!"

"Yes, Gramma?" young Jim said.

"Put your wraps on," Grandma Hickathier said severely. "You'll catch cold."

"Yes, Gramma," young Jim said, and leaving both his coat and sweater on the ground, he got in beside his father. As they drove off, they heard the old woman shouting at them but the car made so much noise they couldn't hear what she said.

There was no need to turn the car lights on. They could see every rut in the road, and the fences and fields on either side. At the corner where the mailboxes were, young Jim read the sign: "Briggsville 2 mi" without any trouble. The closer they came to the Marvells' farm the brighter everything got. The light was not white like daylight, nor red like firelight. It was like an unusually clear starlit night only ever so much brighter.

The road past the Marvells' was lined with autos. All the cars in the neighborhood were there. The Wilsons' old Dodge and the Cornishes' old Buick, the Ferrises' Oldsmobile, and the Hubbers' old Chevrolet. There were cars from Briggsville and from Big Spring and Endeavor. There were even cars from as far away as Oxford. None of them had bothered to put their parking lights on, with so much brightness all around.

Jim Hickathier pulled the Model T over to the side of the road. He and young Jim got out and pushed their way into the crowd. They met George Wilson, whose farm was on the other side of the Marvells'.

"Quite a turnout," he said, and spat a very bright wad of tobacco juice on the road, some distance away.

"What's goin' on?" Jim Hickathier asked.

"Marvells're away," George Wilson said.

"Know they are," Jim Hickathier said. "Gone to Virginia."

"Well," George Wilson said, "house is shinin', that's all. So's the barn and the corncrib. People don't know what to make of it."

From far up the road came the sound of a siren moaning,

and a brass bell clanging for all the countryside to hear. The volunteer fire department from Montello came in sight. Even before the fire truck stopped, the firemen jumped off in their new red helmets and rubber raincoats and began unwinding the hose. The man at the wheel stood up and asked if anybody had been up to the house to see who was there. Nobody had and nobody was anxious to go.

Two of the firemen started for the kitchen door. They had only taken a few steps when everybody began to smell burning rubber. The two firemen came running back and pulled their boots off as fast as they could.

There was no place where the firemen could attach their hose after they got it unwound, so they wound it up again. Since the light didn't change but stayed a pure constant bluish silver, people got tired of making the same remarks about it and began to yawn. One car after another slipped away. The fire truck started back to Montello with the bell ringing faintly and the firemen clinging to the sides. By daylight there was only one car left, the Hickathiers' Model T. Jim sat at the steering wheel and young Jim cranked. The sun came up before they got started.

The next night the cars were there again before dark to see if the light would come on, and it did gradually, from every board, every windowpane, every shingle, brick, and stone. The light was reflected in the faces of people looking at the Marvells' place, and for the first time some of them remembered about August.

"Where's August?" they said to each other.

"Is August lookin' after things?"

"Wonder what's happened to August?"

All during the next day cars drew up before August's little shack on the other side of the marsh and came to a stop. The people in the cars sat and waited until August's wife came out, wiping her hands on her kitchen apron.

"August is feeling poorly," she said each time. "I didn't have nobody to send word to Mr. Marvell by, but I figured when August didn't show up, he'd make some other arrangement . . . Yes, August is real poorly."

As the car drove away, the curtain behind which August had been peeping fell back into place. He was not in bed but sitting up in a rocking chair. It was his hip that was bothering him, this time. Whenever he sat down he couldn't get up again, so he just stayed in the rocking chair by the front window and waited for cars to drive by.

The day after that, one of Art Anaker's geese was found dead right in the barnyard. There was so much talk about what kind of an animal had killed it — whether it was a fox or maybe a mink or a wild dog or just an extra large weasel — that the farmers stopped paying much attention to the light in the sky. It was still there, though, and helpful to do chores by. They didn't have to carry a lantern around with them, no matter how late at night it was, or how early in the morning.

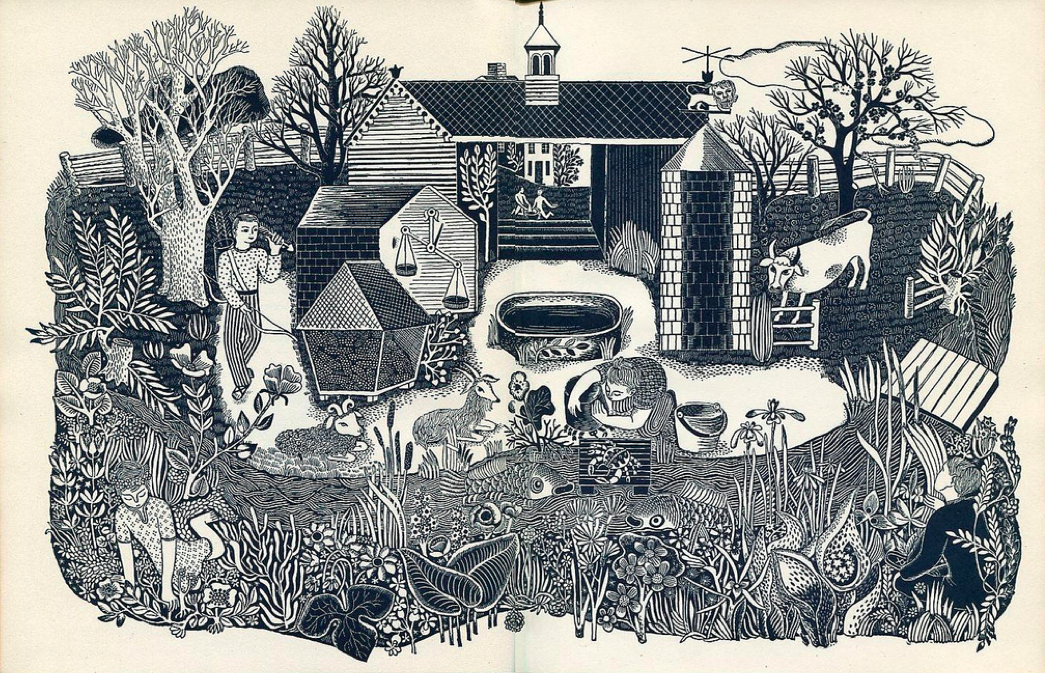

After two weeks August's hip still bothered him, but he grew tired of sitting in a rocking chair, and wondered who was looking after the Marvells' house and animals. Curiosity finally drove him out of doors.

It was such a spring day as comes only once a year, and only in the month of May. The air was damp and sweet, and what had been new buds on the trees the day before were now tiny leaves. The sun felt warm and kind, through August's ragged blue coat. Red-winged blackbirds were singing all around him, and there was one old crow that went "Caw, caw, caw" with happiness.

August meant to go only far enough into the marsh so that he could see the Marvells' barns and anybody who might be moving about there, but he saw something shining above the silo and couldn't figure out what it was. He went a little closer and then a little closer until finally he was standing on the bank of the trout stream that divided the Marvells' hill from the marshland.

From there he could see that the object on top of the silo was a new weather vane in the shape of a golden lion. The old weather vane was a trotting horse, green and rusty with age. Someone must have taken it down and put up this new glittering one that now turned round and round in the spring wind.

August meant to go only far enough into the marsh so that he could see the Marvells' barns and anybody who might be moving about there, but he saw something shining above the silo and couldn't figure out what it was. He went a little closer and then a little closer until finally he was standing on the bank of the trout stream that divided the Marvells' hill from the marshland.

From there he could see that the object on top of the silo was a new weather vane in the shape of a golden lion. The old weather vane was a trotting horse, green and rusty with age. Someone must have taken it down and put up this new glittering one that now turned round and round in the spring wind.

August was about to go limping back across the marsh when he saw two of the largest fish he had ever dreamed of. They were bigger than a man, and they moved easily, serenely, up the steam, in and out of the water weeds. August's mouth dropped open. He forgot all about his hip.

August was about to go limping back across the marsh when he saw two of the largest fish he had ever dreamed of. They were bigger than a man, and they moved easily, serenely, up the steam, in and out of the water weeds. August's mouth dropped open. He forgot all about his hip.

The sunlight, filtering down through the water, shone on the glittering scales of the two fish, on their mild eyes and soft silver mouths. While August was standing there, wondering whether to go home for his fishing rod or jump into the creek, clothes and all, and try to catch the fish with his bare hands, something whizzed by him. It could have been an insect but it was more like the sound an arrow might make. He looked all around and couldn't see anything.

The fish were hugging the opposite bank, and as he stepped on the bridge to cross over, the same thing happened that had happened before. This time August saw the arrow. It came quite close to his face and he had a queer feeling that if the person who shot it had really wanted to, he could have sent the arrow much closer still.

The fish were hugging the opposite bank, and as he stepped on the bridge to cross over, the same thing happened that had happened before. This time August saw the arrow. It came quite close to his face and he had a queer feeling that if the person who shot it had really wanted to, he could have sent the arrow much closer still.

August squatted down in the marsh grass and the wild rice and waited. In a moment he saw, coming down the stream from the other side, a boy who walked proudly but with such a light step that he made no sound. The boy had a silver bow in his left hand and a quiver of arrows slung over one shoulder. He looked like Roger Marvell, from a distance, but as he came closer, August saw that it wasn't Roger after all. This boy was taller than Roger, and broader in the shoulders.

"Humph," he said. "Like to put somebody's eye out if he ain't careful."

The archer crossed the bridge and went off into the marsh without once looking in August's direction, but August knew that the archer knew that he was there. From his hiding place he could see all that went on up at the Marvells'. Apparently whoever Mr. Marvell got to look after the place had brought some animals of their own. In the pasture was a milk-white bull. August had gone to farm auctions all his life and never had seen a bull that could compare to this one. There was also a ram untethered and free to wander over the hillside. And out by the trash pile, munching delicately on whatever he found there, was a goat. August wondered what kind of people could afford to own such fine animals and yet be willing to come and look after somebody else's farm for a few days.

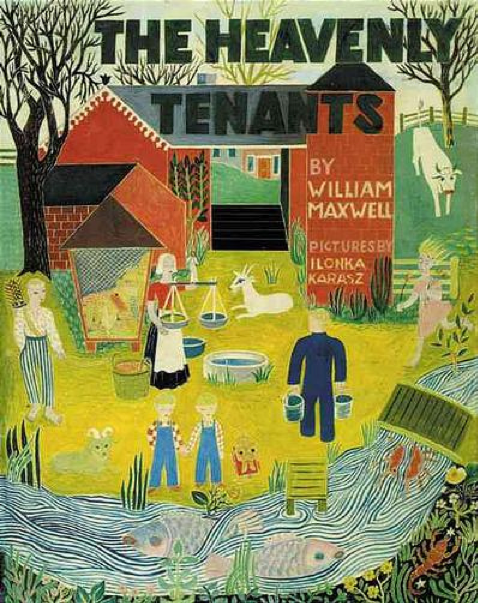

The kitchen door opened and two little boys came out, running and shouting. It could almost have been Tom and Tim. The little boys were twins. They sat down in a sandbox under a pine tree on the lawn and began to build a sand castle. Every time they took up a handful of wet sand, they weighed it on a set of scales.

A man came out of the barn with a pail in each hand, and for a moment August was sure it was Mr. Marvell. Then he wasn't sure. The man looked so much like Mr. Marvell and yet there was something strange about him. He walked down the path to the pier and knelt there, close enough for August to see that he was a stranger. His sleeves were rolled to the elbow and his skin was white and gleaming. When he turned the pails over, to August's astonishment a crab slithered out of one and a scorpion out of the other. The man dipped both pails into the stream and carried them, filled to the brim, back up to the hill to the barn.

August felt his forehead to see whether he had a fever. His forehead was cool but his heart was beating much faster than it ever had before, and he kept wanting to turn his eyes away, as if he were looking directly into a strong light.

He had about decided to go when a little girl about Heather Marvell's age came out of the house and ran lightly down the hill and across the bridge. She stopped suddenly and raised her head, as if she sensed August's presence. But then she went on into the marsh and began to gather flowers. August had not noticed them before, but now he saw flowers growing all along the stream. The were growing between the roots of the marsh grass. They were everywhere. August didn't know the names of any of them. They might have been wild or, he decided, they might be some that Mrs. Marvell, who loved flowers, had planted out here. When the little girl came back, her skirt filled with flowers, she sat down on the other side of the bridge and began to make a chain of them.

Without waiting for her to finish, August withdrew quietly and started back across the marsh. There was no trace of his limp now. He walked quickly and happily. On the way he stopped to gather a little bouquet of marshflowers to take home to his wife.

4

Three weeks after the light first appeared in the sky Jim Hickathier went out to the barn to look after the animals, found himself in pitch darkness, and fell over his own wheelbarrow.

"Well," he said to his sister Libby, when he came back into the house for a lantern. "Guess the Marvells are home."

They were just turning into their drive, as a matter of fact. Their house always looked to them like the most wonderful house in the world every time they came back to it, so nobody thought anything about the faint glimmer that was still over everything.

They went inside and walked through all the rooms. There was a good hot fire in the kitchen stove and every clock in the house was ticking. Roger was hungry but he couldn't think of anything he really wanted to eat. Not even crackers and milk would suit him. Heather sat down with her neglected family of dolls but she was too sleepy to play with any one of them for more than a few seconds at a time. And if Mrs. Marvell hadn't helped the twins undress they would have gone to bed with their clothes on.

Tired though Mr. Marvell was, he went outside to look at the stars. A moment later Mrs. Marvell heard him calling her and went to the screen door.

"The Crab!" Mr. Marvell said.

"Well, what about it?"

"It's back in the sky again! All the time we were in Virginia I couldn't find a single one of the constellations of the zodiac. I looked every night, too, with a telescope. Now I come home and there it is. Something queer is going on in the sky."

"If anything queer is going on," Mrs. Marvell said, "it isn't in the sky. It's right down here. Come to bed. You're so tired you can't see straight."

The next morning when Mr. Marvell went out to the barn he found perfect order, but there was no hay in the manger for the horses, and the cows had not been milked. Their udders were full, and they were switching their tails impatiently.

"Confound that August!" Mr. Marvell cried. He looked around for the milk pails. Instead of the two battered ones he always used, there were two new pails, so shiny that it hurt his eyes to look at them. "Now what did that lazy good-for-nothing have to go and buy new milk pails for?" Mr. Marvell exclaimed irritably, for he was not yet wide awake, and after three weeks, everything seemed strange to him, even the old three-legged milking stool. The more he looked at the pails the more certain he became that August had not charged them at Kimballs' general store in Briggsville. As soon as both pails were filled with foaming milk he emptied one and looked at the bottom to see if there was any store label. All he could find was

"Why," he said out loud, "this looks just like the mark that means the Water Carrier!" He sat and looked at the mark a long time, until the cows complained mildly. He turned then and went on milking.

Before anybody could think of something Roger ought to be doing, he started off through the deep woods. In the path ahead of him he saw a silver arrow and picked it up. It was lighter and more finely made than any arrow he had ever seen. He suspected that he ought to take it and show it to his father, but then his father might say that it was too valuable for him to play with; or his father might try and find out who the arrow belonged to, and Roger didn't want to give it up.

He had never owned anything in his whole life that he loved so much. He held it in his right hand, balancing it on one finger, the way only perfect arrows will balance. Then he got his hickory bow from the woodshed and went through a little patch of timber to the north field, where no one could see him and ask what he was doing.

He had never owned anything in his whole life that he loved so much. He held it in his right hand, balancing it on one finger, the way only perfect arrows will balance. Then he got his hickory bow from the woodshed and went through a little patch of timber to the north field, where no one could see him and ask what he was doing.

He fitted the arrow to his bowstring and drew it as far back as he could. Then with the arrow pointing directly into the sun, he let go. There was a soft sound almost like music. Instead of coming down in an arc halfway across the field, the arrow kept on rising and rising until finally it disappeared in the brightness of the sun.

The twins' sand buckets were just where they had left them, in the sandbox under the pine tree on the lawn. Their little tin shovels were lying alongside. When Tom turned his bucket upside down, what fell out was not sand. It looked more like sparks from his father's emery wheel, or like the smallest stars in the sky. Tim's bucket was full of them also. They poured water over the dry sparks to make a tower that would shine at night, but, instead, the sparks turned into very fine white ashes. The rest of the sand pile was just sand.

Heather was not free to go outdoors until she had helped her mother set the table with the breakfast dishes and put the soiled clothes in the hamper. When she pushed open the screen door it was like Virginia. The warm honeysweet air made her want to lean against somebody the way the cats were leaning against her. From the kitchen steps she could see that the apple orchard was in bloom. That meant white violets by the windmill as well. She thought of going up there but then she saw August coming up the hill and waved to him.

In the end Heather decided to cross over the bridge and see whether any of the marshflowers were blooming. When she knelt at the edge of the path she found what she was looking for. There was a small patch of flowers and they were not like any she remembered from any other spring. They were more like the flowers she sometimes dreamed about. Some had fringed petals and some had petals that were shaped like hearts. Some were as big as her hand and some were no larger than her little fingernail.

Heather thought at first that the marsh must be full of such flowers and went here and there, parting the grasses and trying to find another patch like the first, but apparently there was only that one. When she went back to it, though, the flowers were gone, or else she couldn't find the right place.

August had finished putting down clean straw for the horses when Mr. Marvell came into the barn, picked up the battered old milk pails and put them down again. He opened the door of the harness room and looked in. Then he said, "What happened to the new pails, August?"

"What new pails?" August asked.

"Those two new milk pails that were here this morning."

August shook his head. "I didn't see no new milk pails," he said.

Up at the house Mrs. Marvell stood in front of the kitchen door and rang the cowbell violently for breakfast. When they had all come in and washed and were sitting at the big kitchen table she turned to August and said, "Did the man from the electric light company come out here while we were away?"

August blushed a deep red. "No, ma'am," he said. "I don't think they was anyone here like that."

"It's very peculiar," Mrs. Marvell said. "There isn't a thing out of place, but all morning, no matter what I pick up, sparks fly off of it. And I've been feeling so light. When I weighed myself on the bathroom scales I only weighed a quarter of a pound."

Mr. Marvell, Roger, Heather, Tom and Tim looked at one another. Each saw that the others had a secret which they hadn't told anybody. None of them realized the whole secret — that while they were away the zodiac people with their animals had come down from the sky and taken care of the farm. The whole secret is something very few people ever discover.

One by one the children lowered their eyes to their cereal, and Mrs. Marvell, since no one seemed interested in her lightness or able to explain it, went to the oven and took out a pan of corn bread. The oven door gave off a few faint sparks when she closed it.

"Anyway," she said, "sparks or no sparks, it's nice to be home."