CLEARING WEATHER

CHAPTER I

HOAR FROST

The bent plum trees set in the square of rough grass behind the Blackbird Inn, were as white on this mild February morning as though it were May. Ordinarily their branches were as black with age as they were twisted by sea winds; for beyond the hawthorne hedge was the marsh, across which gales from the north and east could sweep unhindered; and beyond the marsh was the sea. It was neither blossom nor snow which covered the wide-reaching boughs in that hazy sunshine, but a gossamer-light veil of frost which lay upon every branch and twig, and penciled each with a delicate tracery of white. Nicholas Drury opening the door which gave upon the garden, could see that the rime-covered boughs were not stirred by any breath of wind and that even the brown expanse of the marsh lay unrippled by any breeze in the stillness of the winter dawn. Across the tops of the dun and yellow, frost-tipped grasses, he could see the slate-gray water with white riffles where the slow swells curved and broke about Pelman Island and along the rocky reach of Branscomb Head. The horizon was faintly blurred, as though the mist which had lain over the garden all night and had gathered in airy lines of white upon the trees and grass, was now returning whence it had come.

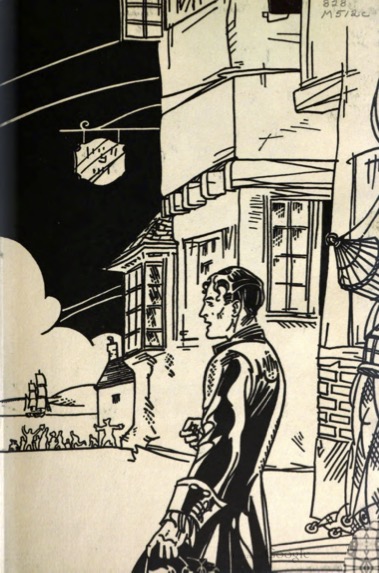

He stood upon the doorstone, a tall boy of nineteen, well knit, with brown hair which, at the back of his head, never lay quite smooth. He was looking across the garden with a glance vague, at first, then growing intent with surprise and curiosity. Finally he passed his hand across his eyes as though to rub away the obscuring weariness of the night just past, and looked again.

He saw that the grass below the plum trees was covered with frost also, each yellow blade beaded with the same perishable whiteness which a touch would destroy. A touch had indeed dislodged it at regular intervals; for all across the lawn leading up from the direction of the marsh was a line of striding footsteps. So faintly were they printed upon that shining surface that at one moment the boy was quite sure he could make out each separate footfall reaching from the far corner of the hedge to the little bow window of the room out of which he had come; yet at the next instant it seemed as though the marks were only the shadows of tree and hedge, or merely a deceiving trick of the sparkling rime. He could only stare and wonder and think, first that he saw them and then that he did not.

Behind him the house was slowly awaking from the troubled slumber of night to the work of the day. Footsteps and voices were going up and down in the passage, and in the stone-flagged kitchen where a lattice window was thrown open. But the voices, for the most part, spoke in whispers, and the footsteps either hesitated or hurried. Once there was the sharp clatter of a plate dropped upon a stone floor, and a man's startled exclamation cut short in the middle as though in recollection of the great need for quiet. Certainly the sounds had little to do with the bustling arrival of travelers. There was nothing of the laughter, the hum of voices, the orders called and the hastening feet which belonged to the ordinary humming activity of a busy inn.

Although it was well situated with its front door upon the very edge of the post road leading north from Branscomb, and its back garden looking upon a broad blue reach of sea, custom was no longer very great at the Blackbird Inn. Travelers indeed were very few anywhere during these difficult times in the years just following the war of the Revolution. Once the highway leading north from Boston had been busy with mail riders and coaches, with packhorses and creaking carts, for Branscomb was no inconsiderable port and had been known for its harbor and its ship building throughout the colony of Massachusetts. Yet to-day there was nothing of this, only the stirring of uneasy feet and a sense of danger and disquiet in every sound drifting out from door or window. Suddenly a man spoke in the passage. His voice was deep, with, under its low tone, a wavering edge of desperate anxiety.

"He has passed safely through the night, but what is the day to bring?"

The more softly spoken words of a woman followed:

"Ah, what can save us now?"

Nicholas, hearing them so close to the door called, though almost below his breath.

"Phoebe, Caleb, see what is here."

They came out together upon the step, Caleb Harmon, a broad-shouldered man with a gray head, but with the ruddy open face of undiminished health and strength. Phoebe, with her smooth hair, placid, gray eyes, and gentle expression was an odd contrast to his breezy vigor.

"There is a storm brewing," she said as she stepped outside.

She was shading her eyes with her hand to look across the garden, for the sun, just then, was bright behind the haze. Then both were intently silent for a moment, for it was plain that they also were staring at the footprints in the white frost.

"As I live," Nicholas heard Phoebe say to herself in a wondering whisper, "here is good fortune come to this house at last. I always knew that it must return out of the sea, whither it was carried away."

"Good fortune?" repeated Caleb. "You are over-hopeful, Phoebe, to read any sign thus. It is high time that some better chance should come our way; but it is my belief that all good luck has fled from this household forever."

Nicholas looked down at his shabby breeches, then glanced up quickly at the window of the room just overhead before he voiced his agreement with Caleb.

"It is true that we have need of good fortune," he said, "but how can it come out of the marsh where no man dwells and from the sea where no ship lies? It is more than likely that these are the footsteps of a thief who stole up to look in at the window and went trudging away again when he saw how little there was within."

"If it was some one peering in," said Caleb, his anxious tone lightening a little, "I believe that I can tell just what it was that he saw. If he came toward morning, as the sharpness of these footmarks would seem to show, if he stood close to the window–and look, he must have done so for there are the two prints of boot soles in the soft earth of Phoebe's tulip bed–if he pressed his face against the glass, I think he observed a young gentleman with rumpled hair, sitting beside a table all set about with ledgers, accounts and legal documents. And he saw that the same gentleman had grown so weary of adding and subtracting figures which all told the same sorry tale, that he had laid before him a fair sheet of paper and, with dawn coming in at the window and with the candle flame burning colorless in the daylight, he was drawing the picture of a ship."

"Did–did you see?" stammered Nicholas, and then chuckled in spite of himself, in unison with Caleb's deep rumble of laughter.

"I would require small wit to see from your hollow eyes that you had not slept, and I would need even less to guess whither your thoughts would stray before the night was over."

Nicholas colored with the quick flush of one whose feelings are apt to be cherished secrets and who is startled no matter how close a friend it is who guesses them. To cover the confusion which his words had produced Caleb Harmon added easily:

"And it seems that this chance of good fortune which Phoebe has foreseen for all of us, is about to take its flight."

The sun had come out for a brief moment through the haze, and under its warmth the delicate, short-lived hoar frost was already disappearing. Only beneath the plum trees and in the shadow of the hedge were the footprints still visible. The three stood watching as these also slowly grew indistinct and vanished. Even after Caleb and Phoebe had gone inside the house, Nicholas still stood staring at the place where the marks had been, as though he would conjure them back again.

The other two had been summoned by a rapping at the main door of the inn which opened so close to the highroad that the swaying, four-horsed post chaises would sometimes draw up with such a flourish that the leaders' prancing hoofs would be almost upon the doorstep. But since there had been no rumbling of wheels this was perhaps only a sailor come, even this early, up from the wharves where ships lay idle in these unprosperous times and through the town, where men without employment walked the streets. He would be jingling two or three sixpences and copper pennies in his pocket and would come to spend what little he had upon Phoebe Harmon's far-famed cookery and her home-brewed ale. But no, it was not even so humble a customer as this, for Nicholas could hear Phoebe say to her husband:

"Make haste to open the door. It is John Ewing from the shipyards and he will wake the master with his knocking."

The grinding bolt was pushed back and the door was swung open, with John Ewing's quavering voice sounding at almost the same instant.

"I came to ask for news, Caleb, of good Mr. Thomas Drury. What is there to tell of him to-day?"

"Nothing but what you heard yesterday," Caleb Harmon could be heard answering. "The doctor was here at sunset and said that he was faring better than for a few days past. He says that there is now but little danger that our dear Master Thomas Drury should–go away from us."

"No, no, I do not mean that," John Ewing's voice was growing higher with anxiety, yet he was evidently trying to subdue it to a tone more proper for that house of sickness. "We heard that in the village yesterday,–that Mr. Drury would recover. Abner Hoxie, the town crier, was calling it in the market place just before the curfew. I came now to ask of Mr. Drury's affairs, of work in the shipyards, of all those things which concern us and our welfare. What tidings are there of them?"

"I can tell you nothing," Caleb answered briefly. "And do you think it is quite fitting that you should come to this place from which the shadow of death has only just passed, that you should be hastening hither so soon to be prating of money and the building of ships, and of all your own small hopes and fears?"

"It–it was not I alone, it was all of them, back yonder in the town, who bade me come," stammered John Ewing. "It is rumored that the work in the shipyards is to come to an end, and if it is truly so, then half of Branscomb must starve. These are desperate times, Caleb Harmon. If Master Thomas Drury fails us, whither can we turn? What can save us now?"

The man's trembling voice, rising high in terror, had uttered the same words which Phoebe Harmon had spoken fearfully in the passage not half an hour before. It was a direful question which found its echo also in Nicholas Drury's heart, as he walked in from the garden to that small room just inside, where, as Caleb Harmon had guessed, he had spent the whole night poring over accounts and ledgers, all of whose balances added up to one result–ruin. The cool freshness from the marsh and the sea streamed in past him through the open door; but could neither blow away the whole of the close heaviness of the air within, nor dispel the cloud of doubt and danger which seemed to hang everywhere.

The boy's uncle, Mr. Thomas Drury, had lain for some weeks, ill to the point of death, in the little bedchamber just above, under the eaves. He had been lodged there, rather than in the best room at the front of the inn, for here the sound of the sea could come in through the window. Drifting up through the town, there came also the pleasant noise of busy hammers from the shipyards of which Thomas Drury was the well-loved master.

He had lain in a stupor for the most part of the time, only occasionally opening his eyes, and saying to Dolly Drury, the younger sister of Nicholas, his deft and devoted nurse, "That sound must not come to an end. Nothing matters if only that may go on. Tell Nicholas. Have you surely told Nicholas?"

He had spent his whole strength and had come near to giving his life also, that the work in those shipyards might continue. He was the great person of the town, since nearly all of the men worked in his boat yards, or made sails and ropes to rig the vessels which he built and which were famous all up and down New England. Such ships as he sent to sea on his own ventures were manned, also, by those seafaring men of Branscomb who could not stop ashore. Although he was the owner of houses and lands besides his shipyards, he had not gathered a great surplus of money wealth. He was content to be master of a thriving industry, to be loved by all of those whom he employed and to be looked upon, at the time the war of the Revolution began, as the firm upholder of the prosperity of that whole community.

It had been at the very outbreak of hostilities that the heaviest blow fell, as though with direct aim, upon his fortunes and upon the shipyards of Branscomb. Although Nicholas was then many years younger, he was never to forget that night of wild uproar when a force of British ships had dropped anchor in the harbor and, having picked up a fisherman in his small boat, had sent by him the command, "Let all the dwellers in this town leave it within the hour, for it is to be destroyed by cannon fire." In those days the conventions of war demanded such a warning before bombardment could begin.

The stout-hearted Branscomb folk had refused to flee, even though the force of Minute Men belonging to that region had, by chance, been drawn away to a muster at the north end of the county, leaving the town almost unprotected. The shipwrights who remained had snatched up weapons of every sort and had offered obstinate battle. Nicholas, only eight years old then, had stood at the window of an upper room in that big house beyond the town where he and his sister dwelt with his uncle, and had watched the red flare of burning boats along the waterside and had listened to the steady boom–boom–boom which meant destruction at every thundering report.

At last, quite unnoticed in the general confusion, he had slipped out of the house and had taken his way along the road to the village, hurrying ever faster and faster, with the light of the fires growing brighter and the noise of the fighting louder as he came near. He had found his way through empty streets, to the rocky open ridge which looked down upon the shipyards.

The fire from the British vessels seemed to be aimed at that special space of ground just below him, where cannon shots were destroying derricks and hoists and were dropping amongst the piles of lumber with one splintering crash after another. On account of the choppy sea in the harbor, however, much of the marksmanship went wide, and struck harmlessly along the rocky shore of Branscomb Head. Nicholas saw more than one big, round iron ball go skipping and bounding past him, as he crouched below a great sheltering boulder and saw a band of sailors, who had landed from the ships, come pouring over the wharves. But there were men with rifles posted in the shelter of boats and scaffolding, who met the invaders with such a volley of well-directed bullets that they faltered and stood wavering. The broad-shouldered, burly officer at their head roared to them to "Come on, there is but a handful to withstand you."

Of a sudden, not a rifle ball but a stout oak billet thrown by who knew what hand, came hurtling through the fire-lit space and dropped him like a stunned bullock. His men, without their leader, broke and ran in every direction, two of them even scrambling up the ridge and stumbling past close to Nicholas in the dark.

"Too much like Lexington," the boy heard one mutter to the other, as he stopped for a moment to look back at the smoke and lights and the seething turmoil below.

Thomas Drury, steady and unruffled, had gathered his men, and had succeeded in mounting and loading four of the serpentine cannon which had been brought the day before to arm the vessel then building. With these he now opened fire, hastening the retreat of the landing party to a wild rout and finally, by well-aimed shots, even forcing the retirement of the war vessels lying in the harbor. Yet before their departure, the British had managed to cut loose the vessels at the Drury wharf, five of them, goodly ships and new built, almost ready to take the sea as privateers. The enemy towed them out to sea and scuttled them, and then made sail for Boston, leaving the Branscomb shipyards full of splintered wreckage and with the vessel on the ways pierced by three great holes through her deck and hull.

Not until the last sailor had taken refuge upon his ship, not until the blazing fires had begun to die down, did Nicholas have knowledge of anything save the surging tumult below. Then he became suddenly aware that he was not alone in his lookout upon that rock-strewn ridge. Only a few yards away, almost in the shelter of the same boulder, a very tall man was standing, so intent upon watching what was going forward that he was as unconscious of Nicholas as the boy had been of him. An instant's upflaring of one of the fires had lit his face for a moment, a darkly handsome face with high color, great slanting eyebrows, and with, just now, an expression of fierce and exulting triumph. To see him standing so close, to know that he was one whom his uncle had called a friend, Darius Corland, the man second in importance to Thomas Drury himself in that neighborhood of town and farming country–it was this which frightened the peering boy far more than the thudding impact of cannon balls. He crept noiselessly away and for a long time kept the secret of that sudden vision untold to any one. It had passed so quickly, had so resembled a bad dream and was so little to be explained, that he could make nothing of it.

The brief and sudden raid had resulted in no very great loss of life, and the next morning every man able to lift a hammer was at work again. Thomas Drury was directing as calmly as though the brush with the British had scarcely broken his night's sleep. The vessel on the stocks was ready for sea hardly a week beyond the appointed time and went forth duly to fight for her country.

"She sank her good share of King George's shipping," Caleb Harmon loved to tell Nicholas. "She had accounted for a round dozen before she went down off the Bahamas, three months before Yorktown."

Such destruction, however, as that single night's work of the British ships had accomplished, was a very great loss to fall upon a single owner. "We have declared war, we must endure its fortunes," Thomas Drury said and went forward with his building. With half his best men under arms, with his gathered wealth growing less and less, he still managed to send ships to sea through the whole of the Revolution. It was not so much the hazards and destruction of warfare which had wrecked his prosperity, it was the disastrous period which came afterwards. In the efforts of a war-torn country to establish government on the basis of that new freedom which no man was used to and which many loudly doubted, the first results were confusion, disharmony and dire poverty for a great mass of the people in the new United States.

Valiant Thomas Drury, looking daily more worn and pale, kept a brave face and labored early and late in his countinghouse down beside the wharves, striving to keep disaster at bay, and to provide work for those men who, in those difficult times, felt that their only support was in him.

Nicholas, now almost nineteen, labored as best he could to help his uncle; but in those intricate matters of dwindling money, of debts and mortgages and bills of exchange he had, as he knew himself, only the smallest of understanding.

He observed anxiously that Mr. Thomas Drury held long councils with a certain man of law, Joseph Ryall, and with his one-time friend, Darius Corland. Once the boy had tried to tell his uncle of seeing that same Mr. Corland watching the fight from the hill, but Thomas Drury had made light of such a tale.

"You must have been mistaken," he insisted. "Darius Corland tells me that he was away in Salem that night and arrived home too late to be of assistance to us."

Whatever were the results of those conferences, Thomas Drury wore always the same look of steady courage, had always the same words of hope and determination to the very end.

That end came upon a stormy evening when he tarried so late in the countinghouse that Nicholas went to seek what delayed his home-coming. He found him all alone in the great empty room, the candles burning low upon the table full of papers, sunk down in his big chair with his head upon his breast. His eyes were closed, his cheeks were flaming with fever and he was muttering to himself. Even the broken and confused words of delirium bore the same burden. "We must go on."

Some passing infection had taken fierce hold upon his worn frame and was wreaking its unchecked havoc.

With the help of Caleb Harmon, the foreman of yards, Nicholas carried his uncle out of the dark, chilly countingroom. The big house beyond the town was out of reach on that night of wind and rain, so Thomas Drury was conveyed to the Blackbird Inn, there to be nursed through long, dangerous weeks by the devoted care of Phoebe Harmon and of Dolly Drury. The fever waxed and waned, relenting a little, then falling upon him with redoubled fury, seeming bound to destroy him in spite of all that could be done by those who so greatly loved him.

Meanwhile, that ruin which he had so courageously kept at a distance was now marching forward in terrible array. It was left for Nicholas to deal as best he could with the debts and contracts, with all the disheartening reckoning of that long struggle against too heavy odds. Former friends had all fallen away; there was no one to whom the boy could turn for honest counsel. Little Mr. Hugh Hollister, his uncle's usual legal adviser, was only agonized and despairing when Nicholas appealed to him.

"Who ever could have thought that Thomas Drury would come to this," he would exclaim, fairly wringing his hands, and could offer no comfort or suggestion of what should be done.

Yet the more Nicholas toiled over the accounts and records of that last desperate year, the more he understood how gallant a fight had been waged by Thomas Drury; and the more heart-breaking it seemed that such a battle must end in disastrous defeat.

It was over the ledgers, letters, notes and agreements that he had been working for the whole of that night, since now a decision must at last be made. His long adding and dividing, ciphering and hoping had brought evidence of only one obvious thing to be done, to declare the business bankrupt and the work of the shipyards ended. That it would mean tragedy and want to half the town he was very well aware. Yet there seemed no other course. In the gray, cold hour when heavy night is turning to dull morning, he had laid a sheet of paper before him and had begun to write out a notice to be posted upon the gate to the yards and the docks, for information of the men who had toiled in faithful loyalty, ten, twenty and thirty years for first one Thomas Drury and then another.

"Let it be known that the work heretofore carried on in these shipyards, on the docks, wharves, vessels and on all property belonging to the estate of Thomas Drury is now finally declared closed and finished–"

Here he had been unable to go on, to write the last words and to sign his name. Instead, he sat long in deep and bitter thought, and at last, in very weariness of effort, he fell to dreaming of happier things, took up another sheet of paper, and, as was his habit when his wits were drifting anywhere they would, he began to draw the picture of a ship.

Had he, perhaps, as he sat there absorbed in thought, heard a faint fumbling at the window, as though a hand had felt of the fastenings, to push it open, and then had drawn back?

As Nicholas stood outside in the morning sunshine, looking at the last fading traces of the footsteps in the grass, it seemed to him that he did have a vague memory of some such sound. But there was no use in thinking of it now; whoever it could have been had come and gone, and even the last fading traces of his footsteps had quite vanished.

It was high morning now, but with the sunshine disappearing, hidden in the thickening haze. John Ewing had trudged away, to take back to the waiting village what little news he had gathered. Nicholas heard him go, walked across to the table and sat down once more to his task. Here was that unfinished document to which he must once more set his reluctant hand. "–now declared closed and finished." He must write the last words and sign his name.

He could see, with such cruel clearness within his mind just how the notice, posted upon the gate, would be read by the first comer; how he would run back to tell the rest; how they would all come crowding about to peer and wonder and to repeat that desperate cry "Ah, what can save us now?"

Some one, looking over the shoulder of another would say, "That is the writing of young Master Nicholas. We had hoped that the lad might help us!"

How could he, at nineteen, do what his uncle had not been able to accomplish? No, there was no blame to rest heavily upon his shoulders, only grief and regret which seemed heavier still. His racing thoughts had no mercy, for they fell to picturing for him, also, the proclamation of the town crier whose duty it would be to announce abroad so important and disastrous an event as the closing of the shipyards. He could see old Abner Hoxie come striding down the street, his bell clanging, the flapping tails of his shabby, homespun coat blowing about his long, thin legs. He could imagine him stopping in the middle of the market square, where all the townspeople would come flocking about him to hear the slow jangling of his bell and to hearken to what he was to say.

Nicholas had watched Abner Hoxie going up and down in that same attire, ever since he himself had been a little boy. He had heard that enormous voice over and over, and had always been reminded, when he listened, of the deep croaking of the biggest frog in Red Pond. What would it be to hear that great voice now crying out the desperate secret which, so far, was hidden amongst the papers on the table and in the heart of that sufferer upstairs.

"Oyez, oyez, oyez. It is to-day made public that Thomas Drury, Esquire, of this town–"

Once more he could not go on. At least, he could take up that drawing to which he had let his mind wander the night before, could crumple it fiercely and carry it to the fire to drop it upon the flame. He must make no more such pictures; for now he could never again hope to be a builder of ships. Yet the paper was still in his hand, when he paused suddenly, his head lifted to listen, his attention caught by a rising tumult of noises outside. There was a rumble of wheels coming from the direction of the center of the town, and with it the sound of an amazing uproar, shouts, the trampling of feet and the thud of flying stones.

"Stop him," thundered a big voice, still at a distance, but carrying even from afar.

A woman's shrill cry followed. "There, he is turning into the lane."

Nicholas stepped quickly to the door, still open upon the garden. From the highway which passed in front of the inn, there branched a small, rutty cart track which led down past the marsh and ended at the very edge of the graveled beach. This byway skirted the garden close to the inn, but was hidden by the tall hedge. A crowd of people seemed to be hesitating at the corner where the lane separated from the post road. Nicholas, also, hesitated for a moment, not knowing whether the tumult, whatever it was, would pass in front of the house or down toward the marsh. At a sound of crackling among the hawthornes, however, he ran down the garden past a great intervening clump of lilac bushes to come face to face with a man who had broken through the hedge and stood for a moment panting and looking desperately about him.

He was not tall, but was quick and lithe. Nicholas' single glance took in his rough, dark outer coat, with a glimpse of color beneath it, and the whiteness of fine linen, observed also his ruffled bare hair and thin, black-eyed face. Perhaps it was because the boy had recognized that great voice shouting beyond the hedge; perhaps it was because, in that instant of impression, he felt that here was one who was more friendless, more hard-pressed and more hopeless than himself, that he spoke so promptly.

"Run close to the hedge, where no one can see you."

He motioned toward the low shed at the corner of the garden, built close against the hawthornes.

"The door can be seen from the house but there is a window at the back. And inside there goes up a ladder to the loft where the hay is."

"Merci, Monsieur." The stranger flashed him a quick and extraordinarily brilliant smile. He was as light and swift as a hare as he ran to the shed, flung back the swinging wooden shutter that covered the window and made an effort to lift himself over the sill. Whether because he was hurt, or merely spent with the chase, he seemed unable to muster the strength, but slipped back, and stood for a moment holding to the window ledge.

Nicholas was at his side in a breathless second. The sounds beyond the hedge were nearer and louder, and again the great voice rose above the others.

"Remember, a hundred pounds if you lay hands upon him."

"Quick," ordered Nicholas under his breath, as he crouched below the window. "Your foot on my shoulder. There, you are in."

The Frenchman swung himself up and was over the sill. He perched there for a moment, poised, looking down at his unexpected ally with that same flashing smile.

"You are Nicholas Drury?" he asked.

The boy nodded.

"Drop within," he cried desperately. "They will be through the hedge in a moment."

"Not in one moment, at the very least three," returned the other breathing a little fast, but with a manner quite unhurried. "In all fairness I must tell you this, my so impulsive friend. I have heard of you in the village, of you and your uncle who are in some distress, and that it is Monsieur Darius Corland of the big voice yonder, who could save you if he would, but instead, is pressing you hard. Is it not so?"

Nicholas nodded but made no answer, so frantic was his desire that the other should cease speaking and disappear.

"No, before I partake of your hospitality, this one thing must be clear," the man insisted. "If you should go to this same Darius Corland and say to him, 'I can tell you where is hidden Etienne Bardeau and can bring you to him,' he would, in gratitude, do anything for you that you could wish. You have only to yield me into his hands to regain all which you seem to have lost."

Nicholas stared up at him open-mouthed, but only in wonder. Then his face lit with a smile that matched the Frenchman's own. "And you think that I would do it?" he said.

"I did not think you would," the stranger answered, his black eyes dancing. "But now we understand each other."

He dropped out of sight below the sill, just as the boy swung the wooden shutter to. Inside, he could hear the man's feet going quickly up the ladder to the loft.

CHAPTER II

A CHAISE AND FOUR

For a whole minute Nicholas stood motionless below the shed window, listening, not to the clamor in the highroad, but to the faint sounds within, to make certain that the fugitive had got to a place of safe concealment. Then the boy, as swift and nimble as he had just been tense and still, ran along the line of the hedge, slipped into the inn and, with as much of an air of unconcern as he could assume, came out before the front door under the swinging sign. Here the whole household of women had gathered, drawn by that strange and approaching uproar. Just as Nicholas came out upon the step, he saw the shouting throng which had come up the street under the elm trees, now stand hesitating for a moment at the turn of the way and then go pouring down the narrow lane which led past the garden. Amid the excitement, his coming was quite unnoticed as he ran out to join them.

At this hour Caleb Harmon and all of the other stout artisans of the town, shipwrights, riggers, rope and sail-makers, were setting steadily to their day's labor; so that here were only the men of lesser employment or of none, very busy now, however, at the task of tracking down a suspicious-looking stranger of whom some one had cried, "Stop him." There was also a handful of women who had deserted their stalls in the market square, and a scattering of sailors from the cargoless ships lying at the wharves. Even though it was market day, here were all the folk who could drop what they were doing or saying on the instant, and give chase when the hue and cry arose.

The rumbling of wheels ceased abruptly as Nicholas saw a post chaise draw up at the head of the lane, with its four sleek horses stamping and plunging under the sudden reining in. The way was too rough and narrow for those high, yellow wheels, but, from under the leather hood there peered forth a flushed face, and that same great voice which had carried over the hedge now called again:

"Do not let the rascal escape you."

At the sound the horses jumped forward, and the driver was forced to give his attention to quelling the whole restive four. A flying stone, thrown by the inaccurate hand of red-armed Molly Green, grazed Nicholas' cheek; but he paid no attention and seized the shoulder of a man in a sailor's coat who was hurtling past him.

"Will you tell me what means all this ado?" he shouted to make himself heard above the din.

The sailor was so much smaller than the long-armed Nicholas that he was unable to jerk himself free; but he fairly danced in the road with rage at being detained.

"Let me go, Master Nicholas Drury," he shrieked. "I almost had him. There's a hundred pounds to whoever lays hands upon the rogue."

"Who is the man?" Nicholas insisted. "And who has told you that there is a reward for taking him?"

"Mr. Corland says so. Yonder he is calling from the chaise. He says–"

Another of Molly Green's haphazard missiles had caught the small sailor on the shin, which he fell to rubbing and for a moment would say no more.

The foremost of the pursuers had scattered across the inn garden, had tried the door of the shed and found it locked, and had come back to stand irresolute in the roadway. "If the fellow has got into the marsh, there is no hope of finding him," Nicholas heard some one say.

The sailor's high-pitched excitement had dropped a little, and he spoke finally in his natural voice.

"The man came through the market square," he began to explain, "buying supplies for a ship, I should judge. French-spoken he was and he paid for his purchasing with a good gold louis d'or. I heard it ring on the table of Gaffer Hindle's stall. Then came Mr. Corland driving over the cobbles and raises a cry, 'Lay hands on that fellow; there's money offered for his capture.' But the Frenchman was as quick as a grasshopper, and dodged in and out and was away up the street with no one of us able to put a finger upon him."

"And whose hundred pounds was Mr. Darius Corland offering?" demanded Nicholas. "Do you think for a moment, Timothy Tripp, he would offer his own?"

"N-no," hesitatingly admitted Tripp. "But he shouted so quickly, and the man made off with such speed, that first one ran after him and then another and–and–"

He looked at the group now gathering about them, as though begging some one else to go on with what was proving an awkward explanation. Molly Green undertook to continue the tale but with little better success.

"I had turned away for a minute's talk with Dame Hindle and, when all the shouting arose, I thought, as sure as I live, that the man must be making off with my fresh eggs. But I bethink me now that I had sold them all before he came."

"Robert Norton, sitting on the step of the barber's shop, cried out that he had seen the man snatch Timothy Tripp's leather money pouch out of his hand," volunteered another woman. "Was it true, Timothy? How much did he rob you of?"

"He took no purse from me," declared Tripp, "and he would have got only twopence and a bad shilling if he had. Nor did he have the look, somehow, of a man who would snatch silver. No, I only saw him running and ran with the others."

By this time Mr. Corland had quieted his horses, had given the reins to his groom, and was striding down the muddy lane toward them. There was a little murmur and then quiet as he approached,

"King" Corland, a very few dared to call him–behind his back. This was not a title of honor, but the term given to those who had leaned toward the side of King George during the Revolution and had given no help in the war for liberty. In other districts these men were being harshly treated by their unforgiving neighbors and many had left the country. But no one in Branscomb could say or prove that Darius Corland had done other than hold himself aloof from both sides of the struggle, and so the man had held his ground. He was, indeed, one whose very appearance would cast a shock of cold water upon the zeal of would-be assailants,–a tremendous figure, so tall that it was scarcely noticeable how heavily he was made. Under his great brows, his eyes had a piercing look before which many a man was prone to stammer and fall silent. He was dressed always in sober luxury, with spotless ruffles and braided coats that fitted with never a wrinkle. His walk was a proud swing which just fell short of an arrogant swagger.

"Have you let him get clean away, you prating fools?" he stormed at them all, as he came near. "Well, it is your loss that you have tarried to talk when you might have had your hands on a hundred pounds."

"Do I understand that it is you who have offered the money for his capture?" asked Nicholas Drury, since the others stood saying nothing.

"No, not I myself. The man is a dangerous trouble maker, known in two countries, whose governments would both pay well to lay hands upon his evil person. An English prison or a French one, they are both gaping for him."

"So?" cried Tripp. "I thought it was an enemy to our own country we were pursuing. If I had caught the fellow, I was to wait until that King George, whom we all love so well here in New England, should pay me the money, eh? Or the King of France? And was I to risk having my head knocked off into the bargain? Why the man had a cutlass too! We have done well to escape without harm. You put the matter on a very different footing, Mr. Corland."

"But the man is a public enemy," exclaimed Darius Corland. "He goes about stirring up evil notions for the upsetting of governments–"

He stopped suddenly, evidently in realization that his words were somewhat ill-advised.

"Indeed, sir," Timothy Tripp caught him up instantly. "You forget that you are in such company, where the upsetting of governments is considered no very evil thing. Some of us have had a few words to say against over-tyrannical rulers ourselves, and have struck a few blows in that cause. And will strike them again, sir, yes, should King George wish to reopen the question of which he had seemed to have enough."

The little man looked very fierce as he spoke, gazing far upward as Mr. Corland towered above him. No one laughed, however, for Timothy Tripp had done his brave share in the war of the Revolution and had been an able sailor and fighter in spite of his lack of size.

Others of the group in the lane murmured and grumbled and shot black looks at the tall, richly dressed gentleman who had roused them to such excitement to no good purpose.

"He has made fools of us, after all," muttered Molly Green.

None of them were quite so daring, however, as Tripp; so that they all began straggling away, some looking shamefaced, some laughing together. Timothy Tripp, whose courage seemed suddenly to wilt, turned abruptly and followed them, so that Nicholas and Darius Corland were left alone in the lane. The gleam of sunshine had been short-lived; for now gray clouds had gathered overhead and the fog had shut down, hiding all sight of the sea. A spatter of cold rain began to fall upon the two who stood each looking in the other's face, the boy with an expression of steady defiance, the man with a glance of cold dislike, neither of which could have been born in that single moment.

"I am not done with the fellow yet," Darius Corland announced. "It is my purpose to send the constable to search the premises of the inn, for the man must be hiding somewhere. Since your uncle is, for a few days more at least, the owner of these grounds, I suppose I must ask you whether he has any objections."

"You know well that he is too ill to say yes or no in the matter," Nicholas returned. He thought of Joshua Barstow, the fat, short-breathing constable, and felt certain that worthy officer would never attempt to climb the ladder to the loft, particularly at Darius Corland's bidding. "I can say for my uncle," he therefore added, "that any person you may bring can search wheresoever he chooses. But why"–a quick afterthought had come to him–"why is a man sought for by the kings of France and England to be hunted down and arrested by a Massachusetts constable? Of what is he accused in a free country?"

"I can find sufficient accusation against him," returned Darius Corland. "If the fellow was clear of crime, why did he run when the cry went up to put hands upon him? No, I can give proper reason why he should be laid by the heels in the town jail, and at least I shall make it so hot for him that he will never show face in Branscomb again."

Some glowering thought seemed to fill his mind, but he put it aside to proceed harshly.

"I know that Thomas Drury feigns illness to escape worse things. And as for you, young Nicholas, you are an arrogant lad and singularly blind to your own interests. If you would serve me, instead of always resisting me at every turn, you would find it far better for your fortunes."

He strode off to his waiting chaise, while Nicholas took his way slowly back to the Blackbird Inn, with never a single glance down the garden toward the shed. His mind was oblivious to everything at that moment, save his desire to steal out and have word with that black-eyed stranger lying in the hay. But he must give no clue to the man's place of hiding, and would have to wait, with what show of calm he could muster, until the energy of the search had died away.

He went into the house and, fearing that his uncle might have heard the disturbance in the lane, he mounted the stairs to the sick room hastily. But as he passed the door of the bow-windowed front chamber, he observed a girl on her knees before the fireplace and stopped to ask:

"Whatever are you doing, Dolly?"

She turned about quickly to look at him with dancing eyes. There was a glint of something in Dolly Drury's expression which was not mere liveliness nor mischief but, whatever it might be, it was a thing no person, once seeing, ever forgot. Her eyes were browner than her brother's, and her hair, lying now in rings upon a forehead damp from brisk toil, held in its color hints of bronze and of gold. And her face was such as some one of gay fancy might expect to see perhaps in the depths of a magic-haunted forest, peeping out from behind a tree bole, not the face of a dryad or gentle wood nymph, but that of a bold and saucy faun. Her vivid, gay spirits seemed in no way cast down by the trouble which hung over the whole household, nor by her task, which was that of polishing the tall brass andirons.

"We are making preparations for a great event," she said to Nicholas. "Our good friend, Mr. Darius Corland, has just sent his groom to say that he will condescend to rest under our roof to-night, if he can be sure of having better lodging than any one else. So, if there is a pewter plate that is not shining, or a knob of brass in which he cannot see his noble face, the eye of the great man will of a surety fall upon it."

"And what harm if it does," demanded her brother impatiently. "What care we for what Darius Corland sees?"

"We care much," returned Dolly, wisely, "even though we do not hold him in such high regard as he believes. We do not wish him to say that the Blackbird Inn has fallen into slovenly ways and is suffering from the bad influence of the Drury fortunes. Phoebe has enough on her shoulders, with all of us dwelling here and so little payment. I must even help her where I can."

"Then let me polish the brass," offered Nicholas, but she shook her head.

"Uncle Tom has been asking for you," she told him, "so you must go in to him. I am almost done. Mr. Joseph Ryall, the lawyer, is to meet our dear Darius here, and they will sit here by my clean-scrubbed hearth and drink their cherry toddy and toast their toes and plan for our undoing, bad luck to them."

She was sitting upon her heels now, and pushing her hair away from her forehead with the back of her wrist, all the time looking up at Nicholas with such a glance of piercing inquiry that he said hastily.

"What will both Darius and Joseph Ryall say about the streak of soot on the side of your nose?" and, as she stooped to peer at herself in the bright mirror of the polished brass, he hastened away to his uncle's door.

In the peace and quiet of that little room under the eaves, away from the scant passing on the highroad, with the only sounds the faint hammering and sawing of the shipyards, and the slow wash of the waves on the beach, Mr. Thomas Drury was struggling slowly back to life. His own will, and the supporting devotion of all those about him, seemed to have been the forces holding death at bay, rather than any vestiges of strength left in that tired, wasted body under the blue and white coverlet. Thomas Drury's gaunt, clean-cut face had that transparent look which comes with desperate illness; but there was the spark of unquenched spirit still in the blue eyes which he opened as Nicholas came in. He spoke so low that the boy had to lean over the bed to hear.

"Everything–the ships, the building, the men–everything is going well?"

"Yes, Uncle," Nicholas tried to put into his tone all the strength and energy which the other's voice had lacked. "Everything is going–well, indeed."

The two exchanged a look of complete and affectionate understanding. Neither of them had believed in the outer meaning of what he himself or the other had said. But below the surface each had spoken the truth. That which was going well was the trust and regard which each had for the other, the loyalty and belief between them which nothing could destroy. The look which the man bent upon his tall nephew was one of encouraging confidence; while the boy squared his shoulders and felt more of a man for having seen it.

Nicholas walked to the window and stood looking out upon the marsh, whose sober browns and russets, with tawny or amber-colored streaks here and there, would, before so many weeks, be changing to the pale yellow-green that marked the first beginnings of spring, and would be alive with the whistling red-winged blackbirds which had given the inn its name. Not even the narrowest stretch of sea was visible now through the streaming rain and the curtain of gray fog which had shut down so close. Branscomb Head, stretching far out to sea to the southward, and Pelman Island, opposite the window, were both hidden. The gravel bank rising at the far edge of the marsh might have been the last barrier at the very end of the world.

Wrapped in that blanket of mist, there must surely be a ship lying off the beach, waiting for the fugitive now hiding in the loft. How was he to be got safely away and carried out to that vessel? That was the question over which the boy was knitting his brows and bending all of his wits. To wonder what the man had done to be hunted down by the long-armed power of two countries, what crime he might have committed, was a matter which never entered the mind of Nicholas Drury as he stood at the window staring out into the wet, gray morning.

His uncle seemed to have dropped into a doze, evidently not having heard or heeded the tumult below and therefore not in need of explanations. The boy tiptoed to the door, stepped outside and closed it softly. He heard the noise of arrivals below, for Darius Corland, bringing the officer of the law, was wheeling up to the door in his chaise, and giving orders to every one within reach of his commands. Such was the proper fashion for a man of his special kind of greatness to arrive at an inn.

He was obeyed wherever he went, with respectful promptness rather than with any whole-hearted enthusiasm of service. People of Branscomb were fond of drawing contrast between Thomas Drury, their foremost citizen, and Darius Corland, who stood nearest to him in material worth.

"Mr. Thomas Drury is the friend of all of us," the town and country folk liked to say. "Mr. Corland has great wealth, but what use does he make of it? He spends it on glossy-skinned horses and embroidered coats, or puts it into shrewd outlay which brings back profit to himself and to no other. But Mr. Drury's prosperity, which we help him to earn, comes back to us again."

People said also that Darius Corland would have liked well to spend some of his wealth in buying property from Thomas Drury, in especial that big, red-brick, white-pillared house two miles beyond the town where, before his illness, Mr. Drury had been dwelling with the fatherless and motherless two, Nicholas and Dolly. Those persons who know all that is passing in a small community said that Master Drury had, in spite of many offers from Mr. Corland, steadily refused to part with that pleasant, elm-surrounded mansion built by his father, the founder of the shipyard.

To-day, as he dismounted from his chaise, many were Mr. Corland's instructions to the constable, Joshua Barstow, who heard them all without reply. The mild, plump officer of the law, however, presently set about making a conscientious search of the whole house, even, on Darius Corland's insistence, climbing the narrow stair to tap at Thomas Drury's door. He came down again in as much of a hurry as his stout person ever attained.

"Mistress Dolly bade me be quiet and be gone at once," he whispered to Nicholas and, since Mr. Corland chanced at that moment to be receiving the lawyer, Joseph Ryall, no further mention was made of that unfriendly errand.

Having at last proved beyond a doubt that no hiding enemy was to be discovered within the four walls of the inn, nor behind the settle in the common room or under the four-post bed in the best chamber, nor within the big oven built into the kitchen chimney, the not very eager Joshua set out, with a sigh, to explore the hiding places of the garden, where the cold rain was falling ever more heavily.

Nicholas was relieved to see that Darius Corland, who had followed the search all about the lower rooms, was now content to let the affair go on without his aid except for a stream of commands shouted from the back door.

"Beat all the bushes thoroughly," he called, disregarding the fact that the process sent down a double shower of raindrops to deluge the unfortunate constable. "Go all the way down to the Marsh Road."

He had demanded that the key of the shed be given to Joshua Barstow, and, "Make sure you search every corner above and below," was his final order, as Barstow, his round face red and dripping, came splashing up the path, pronouncing the garden quite empty of Frenchmen.

As he stood by one of the kitchen lattices, Nicholas held his breath for fear he had been mistaken in his confident belief that Constable Barstow would never climb the shaky ladder to the loft. The officer tramped around the corner of the low-roofed building to set the big key in the lock of the door. The entrance to the little stable was not easily in view of the kitchen window, so that Joshua was completely out of sight, for so long that Nicholas' anxiety grew to agony. The fat, gray horse munching corn in his stall could tell no tales, but suppose there should be a telltale rustle in the hay above, a betraying creak of the worn old boards? He stood clenching his hands within his pockets, trying not to stare too fixedly at the point where Joshua had disappeared, and from which it seemed that he could not withdraw his eyes. A soft touch on his arm made him jump with startled suddenness. It was his sister Dolly who looked at him with a spark of excitement in her eyes, but who merely said in a whisper:

"Come with me."

She led him through the kitchen entry, at the very end of the house, where by a long slanted glance across the garden, one could just catch sight of the door of the shed. It stood open and within it, thinking himself quite hidden from view of the windows of the inn, Joshua Barstow was sitting in great comfort upon the milking stool. He had evidently had enough of King Corland's peremptory commands and was taking his own time to rest himself in peace and quiet before he should pronounce the shed free from dangerous enemies. The good Joshua had been appointed to his office during the last year of the war, when all younger and more able-bodied men were carrying arms for their country. So honest and loyal had he proved himself, even though also a little slow and ponderous about the pursuing of his duties, that no man had the heart to suggest that another more nimble person should now take his place.

It was a full twenty minutes later, after time quite sufficient for even so heavily moving a man as Constable Barstow to have examined every corner of the shed, that he finally emerged and pronounced the search concluded.

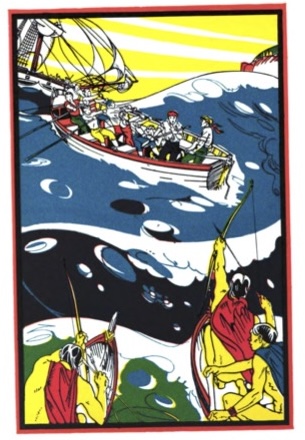

"The fellow must have got away by the Marsh Road," he said, "and have been taken off the beach in a boat by his friends. A whole squadron could lie off Branscomb Head behind this mist and rain, with none of us the wiser."

Darius Corland received his words with a deep growl of disapproval, but he turned back to the fire saying to Lawyer Ryall:

"If I could have aroused the lazy, lifeless townspeople sufficiently, I would have had the marsh beaten from end to end. But at least the rascal will know now that he can never dare to come amongst us here again."

It was now the hour of noon, with all the bustle of preparing dinner for the two important guests and for the post rider who, once a week, came in from the North country, and stopped for a meal before he went forward with the mail for Boston. There was so much coming and going in the rooms which looked upon the garden, that Nicholas must still possess himself of what patience was possible, since he dared not walk across the lawn to the shed, lest some one would observe and wonder whither he was going. He was in the small back room, trying to set to work again upon the great books of accounts, when there was a knock upon the door and Nathan Stiles, the mail rider came in to speak to him.

"I have a message for you, sir," he told Nicholas, "leastways it is for your good uncle upstairs–may Heaven give him back to us well and sound again–and, I calculate, it is you who should hear it in his stead. Ephraim Haveral, up Piercetown way, says to tell you that he has been doing his winter wood hauling and he has for Master Drury four of the best-seasoned, straight, oak trunks you could ever think to see. Hew sixteen inches square, they will, and make the finest keel for a ship yet laid in New England. He can't write, Ephraim can't, nor tell the day of the month by the almanac; but he sends word by me every season what oak and elm and pine he can supply for the shipbuilding, and Master Drury sends back orders for what he wishes to use. ‘About the time you begin to hear meadow larks,' Eph says, 'you can look for my timber wains coming down from the north'ard road.' Shall I tell him to bring them in as he has always done?"

"Yes–no–" Nicholas stammered over his answer. The keel of a ship! What ceremony and rejoicing there had always been in the yards over laying down that first beginning of a stately vessel. Involuntarily his heart had risen at the words and had cried out assent, and then sank heavily in sudden remembrance. Yet he could not bring himself to speak the actual refusal.

It is true of every person that there is some special work to which his hand, mind and heart turns more than to any other. A very few never discover their best field of labor, and pursue indifferent things their whole lives long. Some do not find the right way until after years have been wasted. Nicholas Drury, however, belonged to neither class. He knew, from the earliest time that he knew anything of the world which toiled and teemed about him, that he must build ships. There was much in him of a dreamer, more of a creator. He had worked with hammer, chisel and calking iron among the men so that he might know all parts of the labor which went into a completed vessel. He had an accurate eye and hand for making the drawings which guide the modeling of a ship's hull; he had, already, intricate knowledge of the mysteries of sheer, curve of bow and stern, rake of masts and camber of decks, all of which determine a vessel's speed, buoyancy, and the safety with which she will carry men and goods upon the high seas. He had a mind for instant, clear-cut visions, so that he could look at the rough beams and timbers and see how they would look when cut and fashioned to show the hull's first splendid outline; how the bare vessel would look when clothed with masts and sails and rigging, and how the completed ship herself, tall, white and alive, would at last sail away into the blue distance, carrying men's hopes and lives. Was it great wonder that he stood hesitating, unable to answer Ephraim Haveral's message with either refusal or consent?

"I must tell you later," he said lamely to the waiting Nathan Stiles. "Perhaps I may have opportunity to–to talk of it with my uncle."

He knew that there was really small chance of taking such counsel, yet in no way could he summon resolution to send abroad that message of despair which would be carried by a downright "No."

"I can take word to him when I ride north again," Nathan said. "And my respects to your good uncle, sir. There's not a man in the whole countryside but is lamenting his grievous illness. They come out of the houses as I ride by and ask, second for letters and news of the day, but always first for the special tidings, 'How fares Mr. Thomas Drury?'"

He went out leaving behind him a spark of good cheer in that message of regard from all the friendly folk up and down the North Road.

Presently feet went down the passage to the main door, accompanied by a muttering voice of discontent which could be none other than the constable's. Warmed and fed with an abundant dinner in Phoebe's pleasant kitchen, he was still not appeased, and as he stumped along the corridor and out at the door, he was grumbling his displeasure at being brought out into the rain to do Darius Corland's bidding.

"A plague on him–his whims and his fancies–dangerous characters, indeed! Who's to run back and forth at Darius Corland's orders? Not Joshua Barstow! No, say I."

The front door slammed, while Nicholas, laughing aloud for the first time that day, set himself again to that endless reckoning of accounts. But in the end he made no further pretence, even to himself, that he was working; he was only biding his time.

The minutes passed, then an hour, then more. Since he had been awake the whole of the night, he began to be very drowsy as he waited for the inn to fall quiet. At last he told himself that he would not again look at the wag-on-the-wall clock until the sound of voices and passing feet had finally come to an end. The rain was pouring down steadily, a chill, cheerless winter rain, which would presently turn to sleet or snow. About the eaves the wind was beginning to whisper, and at intervals would drive the cold drops in sharp rattling against the window pane. By dint of sheer patience, by long gazing at the pages before him and turning one now and again, he wore away the hours until midafternoon.

Phoebe Harmon went through the passage, carrying wood to replenish the fire in the room where Darius Corland sat with Mr. Joseph Ryall. Nicholas took the heavy birch logs from her and carried them to the door where he stopped and knocked. It was not firmly latched and swung open at his touch so that he heard Mr. Corland saying:

"He need not think to cause me anxiety, this Etienne Bardeau, by showing his black-eyed face in Branscomb. But mark you this, he will not show it here again."

There was something in the tone, however, which lacked Darius Corland's usual firmness and conviction. Was it possible that he was afraid of that quick Frenchman who had fled from him through the market place? That, Nicholas reflected, was a surprising idea indeed!

He was bidden, curtly, to come in. The two were sitting at a table with papers upon it and steaming glasses, while the air of the room was blue with smoke from Joseph Ryall's long pipe. Neither spoke while Nicholas was laying the logs upon the andirons, but when he turned to go out, Darius Corland addressed him.

"Has your uncle, or any person with authority in the matter, come to a decision as to the final arrangement of his affairs?"

"Not yet," replied Nicholas briefly.

Joseph Ryall, a thin, pinched man with a shabby wig which looked too small, sat tapping upon the table with his fingers and regarding Nicholas with a far from agreeable smile.

"You know, do you not, that things cannot possibly go on as they are, that some conclusion must be come to at once?" he said.

"Yes, I know." Nicholas would have given the world to have some clever and ready answer for these two who were merely baiting him, but he could find none.

"Perhaps you are not aware," said Mr. Corland, "that your uncle, a few days before his illness began, had at last consented to part with his house, for which he had so obstinately refused my generous offers in time past."

This time Nicholas could only nod. He had come across a note to that effect in his uncle's writing. The fact had proved to him beyond any other how desperate was the situation. Darius Corland, he knew, had long been casting covetous eyes upon that comfortable, dignified dwelling, as though he felt certain that, could he once become its owner, something of its dignity and importance would attach to himself and he would at last become the most worthy man of the neighborhood.

"Although things are now not quite the same," Mr. Corland observed, "I am still prepared to carry the agreement to an end. If you are acting for Thomas Drury, I will offer you what I offered him."

He named a sum, to which Nicholas answered quickly:

"That is not the amount put down by my uncle as the price agreed upon."

"It is what I offer now," replied the other coldly. "You can accept or not, as you see fit. And even you can understand that such an amount, liberal as it is, will do very little toward carrying forward the involved business of Thomas Drury."

"A sad tangle, a sad tangle!" commented Joseph Ryall, yet smiling so complacently that Nicholas knew how his lean fingers were itching to pick the bones of the Drury fortunes.

"I will let you know what conclusion–we come to," the boy said, and went out, closing the door behind him, but not quickly enough to avoid hearing Joseph Ryall's suppressed:

"Tee-hee, a bankrupt pauper brings in our firewood and tries to ape the manners of a lord!"

Running down the stairs and seeing Phoebe still in the passage he said:

"I will fetch more wood from outside," and made for the kitchen door.

"Not in all this rain, Master Nicholas; it will not be needed until morning," she protested, but he, seeing an excuse at last for getting into the garden, merely shook his head and hastened on. As he sped through the kitchen, he paused to glance into the larder, caught up, from the shelf, a round of cheese, a loaf of bread which he wrapped hastily in a napkin, and a jug of home-brewed ale. Tucking what he could of these spoils under his coat, he ran through the entry, making apparently for the woodhouse. Once out of sight of the door, he made a long compass all around the garden behind the hedge and finally found himself below the shed window. He set his provisions upon the sill, swung himself up with ease, and dropped inside.

He stood still, listening intently in the dusky quiet. The gray horse in the stall shifted and stamped and finally looked over his shoulder with a questioning whinny, as though wondering why his friend, Nicholas Drury, did not come to his side with an apple or a carrot or at least a friendly pat. But sounds from above there were, for a little time, none at all. At last there was a soft footfall, and a faint, very faint ringing of steel.

Evidently the man above had no notion whether it was friend or foe who had entered below him, and was plainly preparing to receive an enemy with ready cutlass.

"Will he run me through in the dark as I come up the ladder?" the boy wondered. If the fellow were to be stricken with panic, such a thing might easily occur. He dared not call out to announce his coming. But an instant's memory of the light-hearted and perilous delay, while Etienne Bardeau set forth the advantages of betraying him, stilled any doubts in Nicholas' heart. He began to mount the ladder.

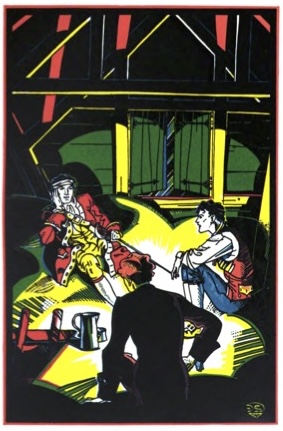

The loft was piled high with hay which rose in mountains all about the sides and left only a small clear space in the center of the floor. The wide opening under the peak of the roof, from which the wooden blind had been partly swung back, gave sufficient light to show a tense, waiting figure, with cutlass out and on guard, standing erect and ready, poised in the single spot where there was space for fighting. Not until Nicholas had stepped from the ladder and had spoken, did Etienne Bardeau drop the point of his weapon and come forward.

"It is you," he said. "I might have known from the lightness of your climbing that it was neither Darius Corland nor his friend the constable. Nor would that soft-stepping rogue, Joseph Ryall, have come anywhere so close to where steel might be drawn upon him."

"You know Mr. Ryall too?" Nicholas asked, as he set down his offering upon a level mound of hay.

"Mais oui, I know them both well, and that they are a more precious pair of rascals than any one hereabouts probably suspects. They managed to do much to aid and abet the enemy while the war was in progress; but that small quarrel is over in spite of them and they can do little further harm. The two of them are in ever-present terror lest the tale of their past doings may come to light even now, and they are in equally vivid hope that trouble will break out again, and that there will once more be congenial work for their hands to do."

"I had never thought that Mr. Ryall had Tory leanings," said Nicholas.

"He is a closer-mouthed man than Darius," the other answered, "and has need to be, for he cannot dominate men as does his big friend, and must cajole since he cannot command. I have known of them of old. It is my business to go and come, to see how men are feeling and thinking and acting, and, where it is possible, to slip in a word to awaken this one here and that one there, to the vision of liberty."

He sat down upon the hay rather abruptly, while the boy put before him the food which he had brought, and, somewhat awkwardly, invited him to eat.

"You are a good friend indeed," the Frenchman said, "not only to rescue a man from the ungentle hands of your fellow townsmen–and women–but to remember that he might be starving besides."

He made a great show of beginning to refresh himself and took up the jug for a draught of Phoebe's ale, then he set it down again precipitately after a single taste. Even in the dim light it was so plain that he was making polite efforts not to pull a wry face that Nicholas was forced to laugh.

"Your climate, and the strange liquids which you swallow so bravely are the only things in this good New England which I cannot learn to regard with affection," his guest declared. "My mother was English, so that I should have as much leaning toward your ways as I have ease in speaking your tongue; but there are a few tricks no man of French blood can learn. He will shiver in your northeast winds, and he will choke upon your strong drink."

He began breaking apart the loaf of bread while Nicholas, seated on the hay opposite him, began to make shy but earnest attempts to learn more of who this stranger might be.

"You have no need, surely, to preach the doctrine of liberty in America," he began, as a hopeful opening.

"No, but America has still to learn that it is one thing to win liberty and another to hold it. All the world is watching to see whether this great effort of yours is to live or die. As your cause prospers, so shall others begin to hope that theirs also may succeed."

Nicholas observed that he was not really eating, and also that the strength of his voice did not quite match the gayety and spirit of its tone. Yet the boy was so full of eager questions that he could not forbear putting more.

"Have you been treated, in other places, as you were here?"

The man smiled as though in memory of an entertaining incident.

"No, not in many places. It was, for instance, a whole year ago that I was last molested upon a wharf in your southern city of Charleston, whither I had gone ashore, and was now waiting for the boat which was to carry me to my ship. An officer from a British vessel in the harbor, together with a company of sailors from his vessel, came tramping by and chanced to hear me speak in my own tongue to a Negro longshoreman from New Orleans. The officer stopped, looked at me with dislike and suspicion, and finally stepped close to shake a big fist in my face.

"'Were you talking of me, you French spy?' he roared and swung a blow at me that would have struck me off the edge of the wharf had I not been–ah–just a little quicker than he. When his men saw him fall they closed in about me, and my one-time friend, the black, being a fellow of no very bold heart, made off across the docks, his voice uplifted in terror. There was scarcely another person on the water front at that hot and sleepy time of day, and yet assistance came to me, help almost as unexpected and ready as yours. You are a friendly nation, you Americans."

"Who helped you?" demanded Nicholas, impatient to know the rest, as the narrator paused.

"I had, earlier, taken note of a certain lad, a year or two older than you, I should believe, and with very red hair. He had been walking up and down somewhat aimlessly, looking at the ships, but apparently having no business with any of them. Now I was to notice him again, for he came flying into the midst of the group like a bolt of lightning, leveled one astonished sailor man with a blow on the jaw and dropped a second with a thump in the pit of the stomach. Together we stood off the others until my boat came up, and we both jumped in. He said that the British sailors had, as though by accident, jostled him as they passed, and that he was longing for reasonable excuse to return the compliment in kind. He told me further that he had come to Charleston seeking to take ship for–as he said–almost anywhere, and was quite ready and happy to voyage with me."

Nicholas chuckled. "I wish I could have seen it," he observed. Then he added in more anxious tones, "What right could the British officer have to call you a–a–"

"A spy?" Etienne Bardeau smiled reassuringly. "Be of good cheer, I am far from that. I am only one who thinks that freedom for all men is as just a thing on our side of the sea as on yours, and who goes about trying to arouse men to see what are their true rights. Into my own land of France I am forbidden to come, under threat of death. It seems that my very humble words concerning liberty for all mankind have drifted so far as the ears of the French king, who has honored me by feeling a little uncomfortable on my account and has sent many of his stout gendarmes to seize upon me if they can. But they cannot."

He paused for a moment and then continued, "And in England, where I have also lived some years, they talk of me as too great a friend of revolutions for their taste and seek to cast me into prison."

"But here in America," pursued Nicholas, "surely you are safe with us."

"Yes, save when your countrymen grow a little overwrought," the Frenchman reminded him. "And who can blame them, for the times are difficult and none are sure what is to come to pass? I did not wish to use my cutlass upon those who had done me no real wrong, and so thought flight was the only course. Even here, though the law cannot well lay hold upon me, bold hands can, and would put an end to my free coming and going."

He had sat upright to relate his brief tale; but now he leaned back against the beam behind him and abandoned any show of eating. His cheerful talk went on for a little and then grew suddenly uncertain and halting.

"That little brown sailor, who so resembles a monkey, and who was at the head of the chase–it was his hand, I think, which flung a stone and cut the back of my head rather more deeply than was quite convenient to me. I have sought to stanch the blood which flows down under my coat, but without success. It is nothing, nothing, but I must crave your pardon, my dear young monsieur–I cannot partake of this feast which you have so kindly set before me. I seem a little sick and giddy–" his voice was stumbling, although he still strove to speak lightly. "It is only the passing–discomfort of–a moment, and would, without doubt, afford great pleasure to our friend Darius–"

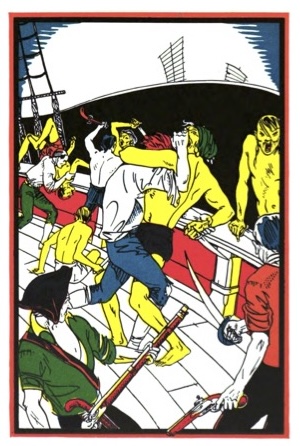

Nicholas, with an exclamation of dismay, jumped up from his place and strode across to where Etienne Bardeau, still smiling, though with a very white face, had slipped back against a soft pillow of hay. But just as the boy was about to stoop over to take account of the other's hurt, a sudden blow aimed at his head from behind assailed him with staggering violence.

He stepped back, throwing up his arm, but had no opportunity even to look over his shoulder at his unexpected antagonist; for a second blow sent him crashing against a beam so that he seemed to spin away into a dark well of space, full of fiery and whirling stars.

CHAPTER III

THE MARSH ROAD

From that brief blackness into which he had been plunged, Nicholas came drifting up again, to hear words spoken which still sounded a very great way off.

"It is too dark in this shadowy place to see aught plainly," Etienne Bardeau was saying: "Close the window, Michael, and fetch a lantern. I saw one below, hanging from a peg beside the door. We must have light to know what harm has been done."

"Have I murdered him? And your own hurt, Etienne, how grievous is that?" questioned a second voice, low-pitched and with an intonation so new to Nicholas' ears that, dazed as he was, he wondered at it dimly.

The Frenchman answered quickly, "That is no more than has come to me a score of times. But if this lad is really injured, it is a desperate business indeed."

Nicholas opened his eyes presently and blinked at the ruddy light of the small lantern which had been set upon the floor in a space cleared of hay. The fine dust floating in the air made a halo of tiny rays all about the red flame, at which he stared in dizzy curiosity before he bent his awakening wits to look further. Then finally, lifting his glance, he saw two faces bending over him, that of Etienne Bardeau, and another, whiter even than the Frenchman's, and crowned with a shock of hair which, even in that uncertain light, showed a brilliant red.

"I thought, as I stole up the ladder and saw you leaning back in the hay with him above you, that he had done you some injury and was about to do more," he of the red head was explaining rather sheepishly to Etienne. "What a fool I have been."

"Tiens, you were as swift with your vengeance as though you were the brave St. Michael himself," replied the Frenchman. "But see, he is moving. Do not be so downcast, my good friend. I am grateful for your zeal, and I truly believe Monsieur Nicholas Drury has not come to any great harm."

Nicholas was, indeed, sitting up now, forced to hold his swimming head with one hand, but otherwise very little the worse for the sudden onslaught. He grinned cheerily at the red-haired boy whom Etienne now presented as:

"The lad whom I met upon the wharves of Charleston as I had but now been telling you. He has amply justified my account of him, that he is a swift striker and a very good friend to me. His only fault is that he is prone to forget he is possessed of the strength of Samson."

Michael Slade, the color coming back into his distressed and still abashed countenance, began a stammering apology. His clothes suggested that he was a sailor, yet his manner and speech were certainly not those of a man before the mast. Nicholas could not bear to let him finish, and stood up to show that he was able to keep upon his feet. "There is nothing to be sorry for," he assured his assailant. "Such a bump on the head could harm nobody greatly."

Michael explained how in the course of the day he had come twice to the wharf in the ship's boat where he was to meet Etienne, and had waited long and anxiously for his friend. He had finally heard "from a little brown sailor" about a Frenchman who had fled through the streets from Mr. Darius Corland.

"I had to pull back to the vessel finally, feeling troubled but sure that no real harm had come to you," he told them, "but when it began to grow dark, I was more anxious than ever and I begged the captain to let me take the dinghy and go ashore to seek you. I landed in the cove above the harbor, north of Branscomb Head, where we had left you in the morning. As I came up the lane, a gust of wind brought me your voice from the window above. I slipped through the hedge, saw where you must have climbed in, and followed. I could hear that you were talking to some one and as I did not know whether you had fallen into the hands of friends or enemies, I came up the ladder without a sound."