NEW LETTERS AND MEMORIALS

OF JANE WELSH CARLYLE

LETTER 111

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Auchtertool Manse, Sunday, 5 Augt., 1849.

Thanks for your Letter, dear John, - come an hour ago, with one from Plattnauer, giving the news of Mr. C., which he has not time, it seems, to write himself. I send it at once, as your Mother will find any news better than none.

Certainly the Letter-department here is arranged on an entirely wrong basis. The delay is monstrous. I cannot write at any length to-day, for fear of stirring up my head into a promiscuousness! The late hours here don't suit me; - in fact, there is a good deal in life here that don't suit me; and which is the more trying because it is wrong, and because one "feels it his duty" to be in revolt against it. Breakfast at ten - dinner nearer seven than six - "dandering individuals" constantly dropping in - dressing and undressing, world without end! All that is so wholly out of place in a Scotch Manse. And the chitter-chatter!

If my Uncle could only speak intelligibly I should get good talk out of him; but since he lost his teeth his articulation is so imperfect that it needs one to be used to it to catch one word out of ten.

By the way, I must not forget to tell you his criticism on your Dante. We had been talking about you the other night, and then we had sunk silent, and I had betaken myself to walking to and fro in the room. Suddenly my Uncle turned his head to me and said, shaking it gravely, "he has made an awesome pluister o' that place!" "Who? What place, Uncle?" "Whew! the place ye'll maybe gang to if ye dinna tak' care!" I really believe he considers all those Circles of your invention.

You are going to let Rosetta slip through your fingers; her Brother is going to take her home to Germany in two months. Or will you go and propose to her there, and take me with you?

Walter performed the marriage service over a couple of colliers the day after I came. I happened to be in the Study when they came in, and asked leave to remain. The man was a good-looking young man enough - dreadfully agitated, partly with the business he was come on, partly with drink. He had evidently taken a glass too much, to keep his heart up. The girl had one very large inflamed eye and one little one, which looked perfectly composed; while the large eye stared wildly and had a tear in it. Walter married them very well indeed; and his affecting words, together with the bridegroom's pale, excited face, and the bride's ugliness, and the "poverty, penury, needcessity and want" imprinted on the whole business, - and, above all, fellow-feeling with the poor wretches there rushing on their fate, - all that so overcame me that I fell a-crying as desperately as if I had been getting married to the collier myself. And when the ceremony was over, I extended my hand to the unfortunates and actually (in such an enthusiasm of pity did I find myself!) presented the new Husband with a snuff-box(!) which I happened to have in my hand, being just about presenting it to Walter when the creatures came in. This unexpected Himmelsendung finished turning the man's head; he wrung my hand over and over again, leaving his mark for some hours after; and ended his grateful speeches with "Oh, Miss! - Oh, Leddy! - may ye hae mair comfort and pleesure in your life than ever you have had yet!" - which might easily be! Walter, infected by my generosity, presented the Bride with a new Bible. The coal-pit would ring next day with the "gootlock" which had "followed them to the Orient."[1]

But there, you see, is a long Letter; and my head is aching, and that is stupid. I must go and sit in the Garden. All the House is at Church.

Your affectionate

J. W. C.

LETTER 112

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, Saturday, 'End of Oct., 1849.'

Cool! upon my honour! I write you a long, charming Letter, tell you everything I know and some things more, - and far from making me a "suitable return," you make me no return at all! ... I have taken a spree of Novel reading, too, - read Shirley last week, by the Authoress of Jane Eyre,[1] and one of Trollope's, - having been taken one day to Mrs. Procter's to see Trollope in her own house, and introduced to her as "a friend from the Country" (that at my own desire, for fear that she would return the call); and having found her a shrewd, honest woman to hear talk. But her Book is rubbishy in the extreme; and Shirley isn't much better. That spell of Novel reading, and a dinner at Knight the Publisher's, to patch up a feud with Harriet Martineau, is all in the shape of amusement that I have taken since my return, - and not much more amusing than darning stockings. ...

Darwin is come back, but I have not seen him yet. Miss Wynn is come back also, and her I have seen, once, in a clatter of Parrots and little cats and dogs, with which she solaces her loneliness, at the top of the house. Bölte is still in Germany imbibing "the new ideas." Anthony Sterling has got Harriet Martineau going to visit him for a couple of days next week - or rather going to visit his lackadaisical Governess. ... He has found a new outrake for his superfluous activity in a small Printing-press he has set up at Headley. With the power of not only writing verses but printing them, one may live a little longer.

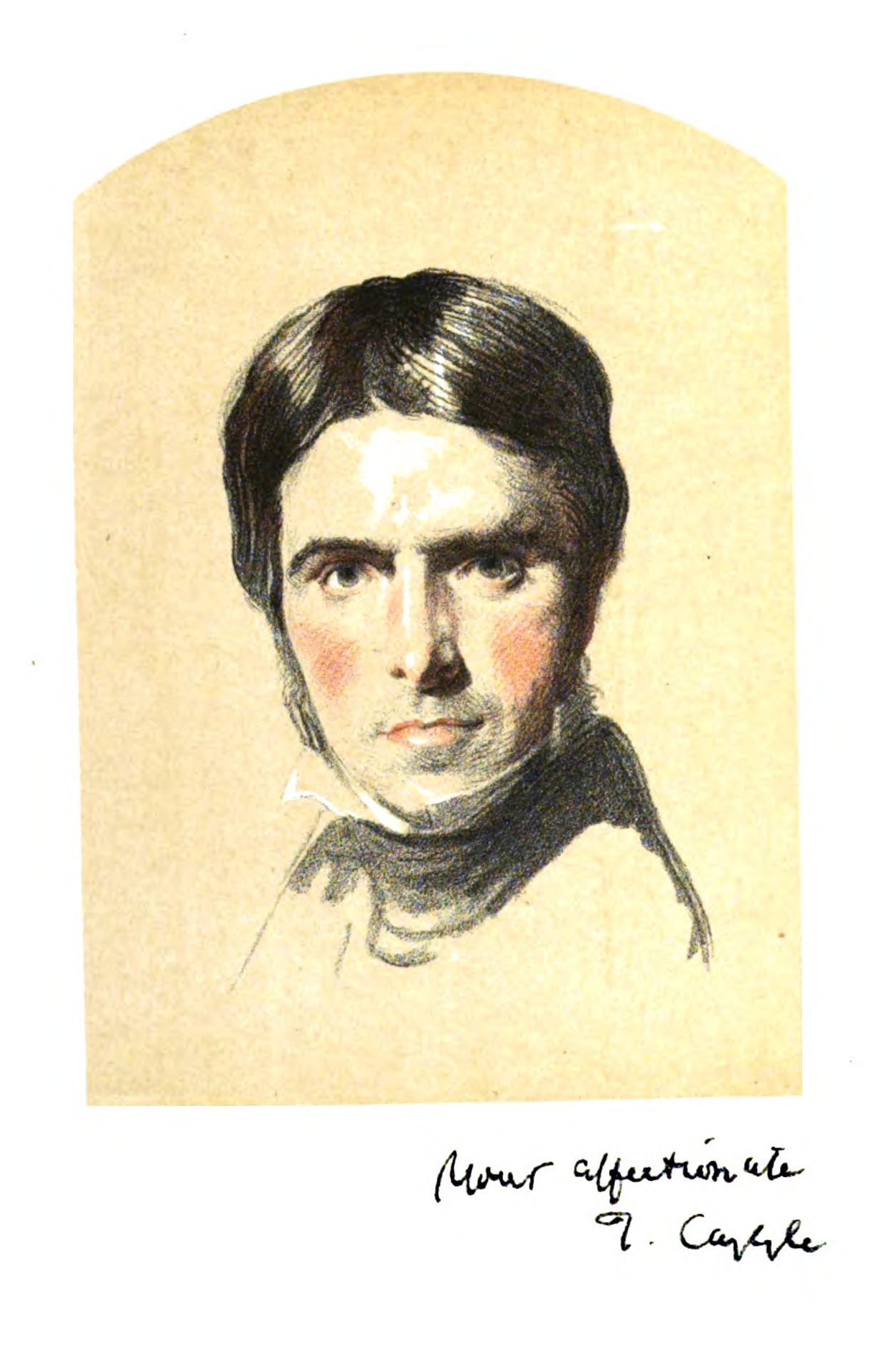

Please to write, tho' it be but with "somebody waiting to take the Letter to the Post-office." We want to hear of your Mother very often till she be quite recovered. And really, considering that I am your patient, - to urge no other claims, - you ought to keep an eye upon me, to be sure I don't poison myself with the prodigious assortment of pills I am continually swallowing. I write to-day at Mr. C.'s suggestion, who has only time to "add a postscript," the Painter Carrick having got hold of him again. - Love to them all.

Yours ever affectionately,

'J. W. C.'

LETTER 113

To John Forster, Lincoln's Inn Fields.

Chelsea, 7 November, 1849.

Yes, dear Mr. Forster, on Wednesday, that is, tomorrow week, the "Great Fact" shall, Deo volente, get itself accomplished.

Meanwhile do not trouble to send me Shirley: I have just finished that not-masterly production. Now that this Authoress has left off "Corsing and schwearing" (as my German master used to call it), one finds her neither very lively nor very original. Still I should like very much to know her name. Can you give it me? as, if she have not kept company with me in this life, we must have been much together in some previous state of existence. I perceive in her Book so many things I have said myself, printed without alteration of a word.

What a bore that we cannot get done with the Mannings.[1] I begin to fear you will not have the pleasure of seeing her turned off, after all.

Ever inexpressibly yours,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 114

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, '10 December, 1849.'

My dear John - I ought to tell you that I am about again; that is to say, when it does not rain; and that again is to say, at rare intervals. The weather is, in fact, detestable; but it will mend in time, - which can't be said of all the detestable things one knows.

The chief news I have to tell you is that I have got a little dog![2] and can hardly believe my senses! I should never have mustered courage to risk such a great step, had not Dilberoglue, the Greek I know in Manchester, having heard me talking about my wish for a dog, which was merely a "don't you wish you may get it?" actually on his return to Manchester, set about seeking one, and fired it off at me by Railway. And so well has he sought and found; that here is a little dog perfectly beautiful and queer-looking, which does not bark at all! nor whine more than if it were deaf and dumb!! It sleeps at the foot of my bed without ever stirring or audibly breathing all night long; and never dreams of getting up till I get up myself. It follows me like my shadow, and lies in my lap; and at meals, when animals are apt to be so troublesome, it makes no sort of demonstration beyond standing on its hind legs! Not only has Mr. C. no temptation to "kick his foot thro' it," but seems getting quite fond of it and looks flattered when it musters the hardihood to leap on his knee. So, there is one small comfort achieved; for it is really a comfort to have something alive and cheery and fond of me, always there.

My fear now is not that Mr. C. will put it away, but that I shall become the envy of surrounding dog-stealers! Anthony Sterling says, "it is much too valuable a dog not to get itself stolen fast enough." Well! I can but get a chain to fasten it to my arm, and keep a sharp look out.

My cold is away again; but, oh, dear! my "interior" is always very miserable; and nothing that I do or forbear seems to make the least difference. The worst is the dreadful pressure on my faculties. There are kinds of illnesses that one can work under, but this sort of thing that I go on with makes everything next to impossible for me.

Mr. Neuberg is always lamenting your absence. He comes occasionally and plays chess with me, and I generally beat him. What is it that makes that man so heavy? He is clever and well-informed, and well-bred, and kind, and has even some humour; and yet, when he goes away every time I yawn and yawn and feel so dished!

No thoughts of coming back yet? I miss you very bad. Mr. C. bids me tell you to cut out his "Trees of Liberty"[1] from the Nation and send it back.

Ever yours lovingly,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

Kindest regards to your Mother and Isabella and Jamie. - I don't think you will get so well on with your Translation there as here.

LETTER 115

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, 'December, 1849.'

My dear John - I feel as if it behoved me to write to you this morning to congratulate you on a narrow escape. I dreamt over night that you were on the point of being married - to a Miss Crawford from about Darlington! No dream could be more particular; I was not "entangled in the details" the least in the world. We felt much hurt here, that you had kept the thing from our knowledge till the eleventh hour, tho' you gave for reason that you were "afraid of its going back," and then our laughing at you. It had been settled for months however; and now it came out that your long stay at Scotsbrig had been for the object of laying in a great stock of Wedding-clothes! shirts sewed by your Sister Jenny, and coats and trousers world without end, by Tom Garthwait. The whole thing seemed to me questionable, and I was glad to awake. Considering that I did not fall asleep till four in the morning and then (after a dose of morphia) only slept by snatches, ten minutes or so at a time, I might, I think, have been spared the bother of your marriage!

Geraldine's Tale is now going on in the Manchester Examiner. I sent the first three parts to Auchtertool three days ago, desiring them to forward it to you. And do you, when done with it, send it back to myself, as I wish to lend it to Miss Wynn, etc. - It is good, so far - no "George Sandism" in it at all. Indeed Geraldine is in the fair way to become one of the most moral "Women of England." Seriously, she has made an immense progress in common-sense and common decency within the last year; and I begin to feel almost (as Mazzini would say) "enthusiast of her!" Her last Letter contains some details I had asked for respecting Espinasse, who had told me in three lines that he was about to retire into very private life, till some sort of amalgamation were effected betwixt the French and the Scotch blood in him, which "insisted in flowing in entirely opposite currents." I will send that part of the Letter - a wonderful style of proceeding in the nineteenth century! ...

I had a Letter the other day addressed, "Mrs. T. Carlyle, Esq.," from one of Helen Mitchell's Dublin Brothers, - the poor one. He wrote to ask the fact of her leaving here. Since she left Dublin, she had written to none of them till now; and now he said she wrote in "great distress of body and mind." - She was living at Bow; had not been in service apparently since she left the place I got her. What she is doing the Devil I suppose knows. If there were the least chance of saving her, I would seek her out; but there is none. Even the Letter to her Brother, under the present circumstances, has been one mass of lies.

Elizabeth does not go. It would have been the extreme of folly to keep her to her vow, when she evidently wished to remain; and I knew of no better person. So, one day, I asked her if she wished to leave at the end of her month, or the end of her quarter? And she answered most insinuatingly that she did not wish to leave at all, if I were satisfied with her. So I gave her a good lecture on her caprices and sullen temper; and all has gone on since better than ever. Not a frown has darkened her brow these three weeks.

As for Nero, his temper is at all times that of an angel. But yesterday, O heavens! I made my first experience of the strange, suddenly-struck-solitary, altogether-ruined feeling of having lost one's dog! and also of the phrensied feeling of recognising him, from a distance, in the arms of a dog-stealer! But mercifully it was near home that he was twitched up. I missed him just opposite the Cooper's, and the lads, who are all in my pay for odd jobs, rushed out to look for him, and stopt the man who had him till I came up and put my thumb firmly under his collar, - not the man's but the dog's. He said he had found the dog who was losing himself, and was bringing him after me!! and I would surely "give him a trifle for his trouble!" And I was cowardly enough to give him twopence to rid Nero and myself of his dangerous proximity.

I continue free of cold, and able to go out of doors; but that I may be reminded "I am but a woman," I have never a day free from the sickness, nor a night of real sleep. This way of it however is much less troublesome to other people, than colds confining me to my room.

Yours ever affectionately,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 116

To T. Carlyle, Chelsea.

Addiscombe, Sunday, 7 April, 1850.

All well, Dear (superficially speaking). Lady A. was out when we arrived, had been out the whole day; is "quite well" again, looking beautiful and in tearing spirits. Lord A. was here, - nobody else yesterday. He was put on reading Mill's Armand Carrel aloud after tea, and it sent us all off to bed in the midst.

This morning the first thing I heard when I rose was Miss Farrar "rising into the region of song" outside; and looking out thro' the window I saw her, without her bonnet, in active flirtation with Bingham Mildmay, who had just come.

They are all gone out (Lady A. on her pony) to the Archbishop's grounds. I went a little way with them, but dropt off at the first bench on the hill. I am not worse for coming, - rather better indeed. I daresay the ride yesterday and the, what Helen used to call, "grand change" was just the best a Doctor could have prescribed for me. - There is a talk of going to Mortlake one day to visit the Taylors - "Barkis is willing."

But if you come to-morrow, as I expect, what am I writing for? I wish you were at the Archbishop's now instead of wrestling with that Pamphlet; and yet, it is not in sauntering about grounds that good work gets done by any one, I fancy. It is a lovely day however, and I grudge your not having the full benefit of it as well as I.

A kiss to my dear wee dog, and what he will perhaps like still better, a lump of sugar!

Yours faithfully,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 117

To Mrs. Russell, Thornhill.

Chelsea, Wednesday, 'Spring, 1850.'

Dearest Mrs. Russell - I am sure old Mary's money must be done now! When you told me what remained of it, I calculated how long it would hold out, and then - forgot all about it! as I do about everything connected with arithmetical computations. You will hardly believe it of me, but it is a positive truth, between ourselves, that I never could say the Multiplication Table in my life, - at least never for a whole day together.[1] I learnt it every morning for a while, and forgot it every night.

HARRIET LADY ASHBURTON,

From an Engraving

By Francis Holl.

Nay, I cannot for the life of me recollect the numbers of my friends' houses! I find them only by the eye. One day I went to dine at a house which my eye had not got familiar with; and found, when I had arrived in the quarter, that I had not only forgotten the number of the house but the name of the street! I spent a whole hour in seeking it, and only found it out at last thro' interposition of providence in the shape of a Scotch footman who had made himself acquainted with the names of his neighbours, - a good Scotch fashion entirely abstained from here. You may fancy the vinegar looks of the Lady of the House and the visitors whom I had kept from their dinner one mortal hour! I made a most unsuccessful visit of it, and of course these people never asked me again.

We have the strangest weather here that ever was seen; and even I, who suffer so severely from frost, begin to feel sick of this unnatural mildness. For the last two or three weeks I have felt as languid as "a serpent trying to stand on its tail" (to use the figure of an Irish friend[1] in speaking of his sufferings from the heat of Munich). If I were within reach of Dr. Russell I would give my volition entirely up to him, to be done what he liked to for six weeks, - the longest trial I ever bring myself to make of a Doctor's prescriptions. But I have no faith in the medical people here: not one of them seems honest to begin with. To get patients and to humour them when got, seems much more the object of these people than to cure their ailments. In fact what can they know about one's ailments, allowing only some three minutes to the most complicated cases! And so I leave my case to Nature; and Nature seems to want either the will or the power to remedy it.

This is a bright day however, - not sloppy as so many preceding ones, - and I must go out for a long walk, and get rid, if not of my biliousness, at least of my blue devils. And so God bless you. Kind regards to your Father and Husband.

Ever yours affectionately,

JANE CARLYLE.

LETTER 118

To John Forster, Lincoln's Inn Fields.

Chelsea, 19 April, 1850.

My dear Forster - ... "With my soul on the pen," as Mazzini says, I declare that if we ever look to not care for you, it is a pure deceptio visus. My Husband may be little - too little - demonstrative in a general way; but at all rates he is very steadfast in his friendships; and as for me, I am a little model of constancy and all the virtues! including the rare gift of knowing the value of my blessings before I have lost them: ergo, if you be still driving out for exercise, please remember your promise to come again. I am sure I must have accumulated an immense number of amusing things during the Winter, that it would do your heart good to hear.[1]

Meanwhile all good be with you; and pray do not fail to observe how much my handwriting is improved in point of legibility. I have not been to a writing-school, nor yet gone thro' a regular course of Copy-lines at home. The improvement has been worked in a manner much more suitable to my impatient temper: by the short and simple means of investing one sovereign of my private capital in a gold pen with a platinum point. Upon my honour the thing writes of itself! and spells too, better or worse. And then the maker assures me that it will "last forever." Just think what a comfort: I shall henceforth write legibly forever! You are the first individual privileged with a sight of its results. I have in fact hanselled it in writing to you, - we shall see with what luck.

Ever affectionately yours,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 119

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, '13 May, 1850.'

My dear John - It was full time you should write! I had just settled it in my own mind that you were falling ill, and could not write; and had romantic little ideas about setting off to help to nurse you! It is "all right," however, and the rightest part of it is that you are coming back. I assure you your absence made a great blank in my existence, such as it is, and I have never even tried to fill it up, - expecting from month to month that you would return to occupy my vacant "first floor" (morally understood). It is amazing how much good one fancies one might get of an absent friend compared with the good one takes of him when he is there! so many things one says to him mentally at a distance which face to face one would never utter a word of!

I hope you will find Nero all you could wish in a dog connected with the Family. I shall take care that he be well-washed to receive you, and not over-full, when he is apt to be, I will not say less affectionate, but less demonstrative than one likes - in a dog. Mr. C. said he wrote that the up-stairs room was, or would be, in great beauty. I have indeed been doing a little Martha-tidying there, - the results of which promise to be "rather exquisite." God defend me from ever coming to a fortune (a prayer more likely to be answered than most of my prayers!); for then the only occupation that affords me the slightest self-satisfaction would be gone! and there would remain for me only (as Mr. C. said of the Swiss Giantess who drowned herself) "to summon up all the virtue left in me, to rid the world of such a beggarly existence."

Speaking of suicide, a woman came to me the other morning from Helen - a decent enough looking person, respectably dressed, and the only suspicious-looking feature in whose appearance was the character she gave herself for sobriety, charity, piety and all the virtues. Her business was to ask me to give the said Helen a character that she might seek another place, otherwise she (Helen) "spoke of attempting her life." "She has been long speaking of that," I said. "Yes, and you are aware, Ma'am, of her having walked into the Thames after she left the last place you found her? Oh, yes, she got three months of Horsemonger Lane jail for the attempt; and if a waterman had not been looking on and taken the first opportunity of saving her, she would have probably been drowned." I said it was well if she had not been in jail for anything worse. Ever since coming out she has lodged with this woman, - her Brothers in Dublin sending her money, - "but very little," - from time to time. But they seem tiring of that, and so Helen thinks she will try service again. I recommended that she should, as a more feasible speculation, go into the Chelsea Workhouse, where they would take care to keep drink from her, and force her to work. As for recommending her to a decent service, I scouted the notion. And the woman herself said she "seemed to have no faculties left," and was always wanting "sixpence-worth of opium to put an end to herself." The object of the woman coming was more likely to get some money out of me. ... But the sun is shining brightly outside, and inside my stomach is very dismal; so I must go out and walk. You will write when you have fixed your time. Love to all.

Your affectionate

JANE CARLYLE.

LETTER 120

To T. Carlyle, Boverton, Cowbridge.

Chelsea, 20 August, 1850.

Only a little Note to-day, Dear,

"That you may know I am in being,

'Tis intended for a sign."[1]And a sign, too, that I am grateful for your long Letters, - my only comfort thro' this black business,[1] which has indeed "flurried me all to pieces." To-day's did not come by the morning post; not till twelve, when I had fallen so low for want of it that I might have had no news for a week! It is sad and wrong to be so dependent for the life of my life on any human being as I am on you; but I cannot by any force of logic cure myself of the habit at this date, when it has become a second nature. If I have to lead another life in any of the planets, I shall take precious good care not to hang myself round any man's neck, either as a locket or a millstone!

... I am now going to lie on the sofa and have Geraldine read a Novel to me all the rest of this day, - writing makes me "too fluttery for anything." I had a misgiving that the corner of the Leader got ruffled Sunday gone a week, in pushing it into that narrow slit in Church Street [Letter-box]. I tied the last with a string.

Give my kind regards to poor dear Redwood, whose feelings I can well understand.

Ever your affectionate

JANE CARLYLE.

LETTER 121

To T. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, Friday night, '6 Sep., 1850.'

Here is a Letter from Lady Ashburton, the first I have had during your absence; neither had I written to her (till I answered this to-day by return of post), partly because she had said at our last meeting that she would write to me first, and partly because in the puddle I have been in I felt little up to addressing Serene Higher Powers, before whom one is bound to present oneself in "Sunday clothes," whereas I have been all this while like a little sweep on a Saturday night! But the Letter you forwarded to me had prepared me for an invitation to the Grange about the end of this month, and I was hoping that before it came, you might have told me something of your purposes, - whether you meant to go there after Scotland; whether you meant to go to them in Paris; - that you might have given me, in short, some skeleton of a program by which I might frame my answer. In my uncertainty as to all that, I have written a stupid neither Yes-nor-no sort of a Letter, "leaving the thing open" (as your phrase is). But I said decidedly enough that I could not be ready to go so soon as the 23rd.

What chiefly bothers me is the understanding that I "promised" to go alone. The last day I saw Lady A. she told me that she could not get you to say whether you were coming to them in September or not; that you "talked so darkly and mysteriously on the subject, that she did not know what to make of it"; that you referred her, as usual, to me; and then she said, "I want you both to come, Mrs. Carlyle: will you come?" I said, "Oh, if he goes I should be very glad." "But if he never comes back, as he seems to meditate, couldn't you come by yourself?" I answered to that, laughing as well as I could, "Oh, he will be back by then, and I daresay we shall go together; and should he leave me too long, I must learn to go about on my own basis." I don't think that was a promise to go to the Grange alone on "the 23rd of this month." Do you think it was? Most likely you will decline giving an opinion.[1] Well in this, as in every uncertainty, one has always one's "do the duty nearest hand," etc., to fall back upon; and my duty nearest hand is plainly to get done with "my house-cleaning" before all else. Once more "all straight" here, I shall see what time remains before the journey to Paris; and which looks easiest to do, whether to go for a week at the cost of some unsettling, or to stay away at the risk of seeming ungrateful for such kindness.

To descend like a parachute; who think you waited on me the night before last? Elizabeth!

I shall send Alton Locke so soon as I have waded to the end of it. There is also come for you thro' Chapman, addressed in the handwriting of Emerson, a Pamphlet entitled "Perforations in the Latter-Day Pamphlets," by "One of the Eighteen Millions of Bores," edited by Elizur Wright. - No. 1. Shall I send it? I vote for putting it quietly in the fire here; - it is ill-natured, of course, and dully so. But I must go and tidy myself a bit, to receive the farewell visit of Fanny Lewald, who has written with much trust that she would "take some dinner with me today at two o'clock." I have not seen her since her return to London. Kind regards at discretion.

Ever yours affectionately,

JANE.

LETTER 122

To T. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, Sunday night, 8 Sep., 1850.

That toe, Dear! it may be a trifling enough matter in itself; but anything that prevents you from walking must be felt by you as a serious nuisance. I don't believe the least in the world that it has been "pricked"; if it had, you would have felt the prick at the time. I think it must be a little case of rheumatism in one particular sinew, and I would have you keep it warm with cotton, and rub it a great deal, and all up the foot, with a bit of hot flannel and some laudanum on it. That is my advice; and recollect that at Craigenputtock I was considered a skilful Doctor, - to the extent even of being summoned out of bed in the middle of the night to prescribe for John Carr, when "scraiching as if he were at the point o' daith!" And didn't I cure him on the spot, not with "eye-water" labelled "poison," but with a touch of paregoric? Meanwhile it is pleasant to know you have a gig to move about in, and that if anything go wrong with it, Jamie will "pey him wi' five shillin'"!

To-morrow I shall lay out two sixpences in forwarding Alton Locke (The Devil among the Tailors would have been the best name for it). It will surely be gratifying to you, the sight of your own name in almost every second page! But for that, I am ashamed to say I should have broken down in it a great way this side of the end! It seems to me, in spite of Geraldine's hallelujahs, a mere - not very well-boiled - broth of Morning-chronicle-ism, in which you play the part of the tasting-bone of Poverty Row. An oppressive, painful Book! I don't mean painful from the miseries it delineates, but from the impression it gives one that "young Kingsley," and many like him, are "running to the Crystal" as hard as they can; and that "the end of all that agitation will be the tailors and needle-women eating up all Maurice's means" (figuratively speaking). And then, all the indignation against existing things strikes somehow so numbly! like your Father whipping the bad children under the bedclothes![1] But the old Scotchman [Saunders Mackaye] is capital, - only that there never was nor ever will be such an old Scotchman. I wonder what will come of Kingsley - go mad, perhaps.

To-day, Sunday, has been without incident of any sort; not a single knock or ring. Emma[2] was at Church in the morning, I reading the Leader and writing Letters - to my Aunt Elizabeth, Geraldine, Plattnauer; - and for the rest, nursing a sort of Influenza I have taken. You ask about my sleep. It is not good, - very broken and unrefreshing; but I get over the nights with less lying awake than in the time of the Elizabethan rows. My health does not improve with the quiet, one would say wholesome, life I am leading; but it is beyond the power of outward circumstances, I fancy, to improve it at this date. And it is a great mercy that I keep on foot. I might easily have less inward suffering and lie far more heavy on myself and those who have to do with me.

... But, "Oh, dear me!" (one may say that, now that you have got such a trick[1] of it yourself) I ought to be in bed, with plenty of flannel about my head! So good-night!

Ever your affectionate

JANE W. C.

LETTER 123

To T. Carlyle, Chelsea.

The Grange, Tuesday, '8 Oct., 1850.'

What a clever Dear! to know merino from the other thing, and to choose the right gown in spite of Emma. Don't trust to finding your horse-rug here. I left it in my bedroom, where it must still be, lying on the trunk behind the door most likely.

I have a vague notion that I am not somehow to get to the railway station to meet you. ... The Taylors are to be dispatched to-morrow, as well as you sent for, and I fancy my going is inconvenient to the servants, who would rather wait at the station than return. Henry Taylor and Thackeray have fraternized finally, not "like the carriage horses and the railway steam-engine," as might have been supposed, but like men and brothers! I lie by, and observe them with a certain interest; it is as good as a Play. ... Rawlinson is here, - a humbug to my mind. I don't believe the half of what he says, and have doubts of the other half. - Adieu till tomorrow.

Ever your J. C.

LETTER 124

To Mrs. Russell, Thornhill.

Chelsea, Monday, 'Nov., 1850.'

My dear Mrs. Russell - Thanks for your pleasant Letter. I enclose a cheque (is that the way to spell it?) for the money. Please to send a line or old Newspaper that I may know it has arrived.

I returned some days ago, rather improved by my month in the country[1]. ... But the first thing I did was to give myself a wrench and a crush, all in one on the ribs under my right breast, which has bothered me ever since; and I am afraid is a more serious injury than I at first thought. Two days of mustard plasters have done little yet towards removing the pain, which I neglected for the first three days.

I found the mud of our London streets abominable after the clean gravelly roads in Hampshire; - it is such a fatigue carrying up one's heavy Winter petticoats. For the rest, home is always pleasantest to me after a long sojourn in a grand House; and solitude, never so welcome as after a spell of brilliant people. One brilliant person at a time and a little of him is a charming thing; but a whole houseful of brilliant people, shining all day and every day, makes one almost of George Sand's opinion, that good honest stupidity is the best thing to associate with.

I send you a little Photograph of my Mother's Miniature, which I have had done on purpose for you. It is not quite the sort of thing one would wish to have, but at least it is as like as the Miniature.

I will not wait till next year to write again, - if I live.

Kind regards to your Father and Husband.

Yours affectionately,

JANE CARLYLE.

LETTER 125

To John Forster, Lincoln's Inn Fields.

Chelsea, 'December, 1850.'

Dear Mr. Forster - Behold a turkey which requests that you will do it the honour and pleasure of eating it at your convenience. The bearer is paid for taking it; so pray do not corrupt his "soul of honour" by paying him a second time.

We were the better for that evening; but we have been to a dinner since that has floored one of us (not me) completely. A dinner "to meet Mary Barton"(?). And such a flight of "distinguished females" descended on us when we returned to the drawing-room - ach Gott! Miss Muloch, Madame Pulszky, Fanny Martin (the Lecture-devourer), Mrs. Grey (Self Culture), - and distinguished Males ad infinitum, amongst whom we noticed Le Chevalier Pulszky, Chadwick, Dr. Gully, Merivale.

Mr. Carlyle has all but died of it! I have suffered much less; - but then I did not eat three crystallized green things, during the dessert.

Nero sends his kind regards.

Ever affectionately yours,

JANE CARLYLE.

Monday.

LETTER 126

To Mrs. Russell.

Chelsea, 12 July, 1851.

My dear Mrs. Russell - It is come on me by surprise this morning that the 13th is no post-day here, and so, if I do not look to it to-day Margaret and Mary will be thinking I have forgotten them on my birthday, or that I have forgotten my own birthday, which would indicate me fallen into a state of dotage! - far from the case I can promise you! For I never went to so many fine parties, and bothered so much about dresses, etc., and seemed so much like just coming out! as this Summer! Not that I have, like the eagle, renewed my age (does the eagle renew its age?), or got any influx of health and gaiety of heart; but the longer one lives in London one gets, of course, to know more people, and to be more invited about; and Mr. C. having no longer such a dislike to great parties as he once had, I fall naturally into the current of London life - and a very fast one it is!

Besides I have just had my Cousin Helen staying with me for three weeks, and have had a good deal of racketing to go thro' on her account, - her last and only visit to me still lying on my conscience as a dead failure; for instead of seeing sights and enjoying herself, she had to fulfill the double function of sick-nurse to me, and maid-of-all-work! ...

I don't know yet where we are to go this Autumn. Mr. C. has so many plans; and until he decides where he is going and for how long, I can make no arrangement for myself. I shall be quite comfortable in leaving my house this year, however, having got at last a thoroughly trustworthy sensible servant.

My kind regards to your Father and Husband. Some one told me your Father was coming to London; he must be sure not to pass us over, if he comes.

I can think of nothing of any use to Mary, sendable from here; I enclose five shillings that you may buy her what she most needs, - a pair of shoes? a bonnet? or some meat? Give her my kind regards, poor old soul. And believe me, dear Mrs. Russell, your ever affectionate

JANE CARLYLE.

I am going to a morning concert and am in great haste.

LETTER 127

To T. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Manchester, 12 September, 1851.

... I am very sorry to hear of your rushing down into coffee and castor so soon, - and any amount of smoking I dare say! For me, I can tell you with a little proud Pharisee feeling, that I have not - what shall I say? - swallowed a pill since I left Malvern!!![1] and I am alive, and rather well. But then, my life otherwise is so very wholesome: nice little railway excursions every day; nice country dinners at two o'clock, - everybody so fond of me! ... It is great fun too visiting these primeval Cotton-spinners with "parlour-kitchens," and bare-headed servant-maids, so overflowing with fervent hospitality, and in the profoundest darkness about my Husband's "Literary reputation." - I have a great deal to tell about these people; but it is needless to waste time in writing that sort of thing.

But one thing of another sort, belonging to our natural sphere, I must tell you so long as I remember; that Espinasse has - renounced his allegiance to you! When his Father was in London lately he (his Father, anything but an admirer of yours) was greatly charmed to hear his Son declare that he had "quite changed his views about Carlyle; and was no longer blind to his great and many faults." Whereon the Espinasse Father, in a transport of gratitude to Heaven for a saved "insipid offspring," pulled out - a five-pound note! and made Espinasse a present of it. Espinasse, thanking his Father, then went on to say that, "he no longer liked Mrs. Carlyle either; that he believed her an excellent woman once, but she had grown more and more into Carlyle's likeness, until there was no enduring her!" The Father however did not again open his purse! Stores Smith, who was present, is the authority for this charming little history, which had amused Espinasse's enemies here very much.

Mrs. Gaskell took Geraldine and me a beautiful drive the other day in a "friend's carriage." She is a very kind cheery woman in her own house; hut there is an atmosphere of moral dulness about her, as about all Socinian women. - I am thinking whether it would not be expedient, however, to ask her to give you a bed when you come. She would be "proud and happy" I guess; and you do not wish to sleep at Geraldine's, - besides that, mine is the only spare room furnished. The Gaskell house is very large and in the midst of a shrubbery and quite near this.

Kind love to your Mother and the rest. ...

Nero is the happiest of dogs; goes all the journeys by railway, smuggled with the utmost ease; and has run many hundreds of miles after the little Lancashire birds. - Oh my! your old gloves have come home with their tails behind them! I found something bulky in my great-coat pocket the other night, and when I put it on I pulled out the gloves. You must have placed them there yourself; for there was also a mass of paper rolled up for tobacco-pipe purposes.

Ever yours,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 128

To Miss Welsh, Auchtertool Manse, Kirkcaldy.

Chelsea, Wednesday, 24 Sep., 1851.

Upon my honour, Dearest Helen, you grow decidedly good. Another nice long Letter! and the former still unanswered! This is a sort of heaping of coals of fire on my head which I should like to have continued.

But I must tell you my news. Well, I lived very happily at Geraldine's for the first week, in spite of the horrid dingy atmosphere and substitution of cinder roads for the green Malvern Hills. We made a great many excursions by railway into the cotton valleys. Frank [Jewsbury] selected some cotton spinner in some picturesque locality, and wrote or said that he would dine with him on such a day at two o'clock, and bring his Sister and a lady staying with them. The cotton spinner was most willing! And so we started after breakfast and spent the day in beautiful places amongst strange old-world, highly hospitable life, - eating, I really think, more home-baked bread and other dainties than was good for us; the air and exercise made us so ravenously hungry. It was returning from the last of these country visits, rather late thro' a dense fog, that I caught my cold; and then came the old sleepless nights and headaches and all the abominable etceteras. I was still stuffed full of cold when I had to start for Alderley Park,[1] and the days I spent there were in consequence supremely wretched, tho' the place is lovely and there was a fine rattling houseful of people; and the Stanleys, even to Lord Stanley, who is far from popular, as kind as possible, - alas, too kind! for Lady Stanley would show me all the "beautiful views," and that sort of thing, out of doors; and Blanche would spend half the night in my bedroom! Lord Airlie was there and his Sister and various other assistants at the marriage. I saw a trousseau for the first time in my life; about as wonderful a piece of nonsense as the Exhibition of all Nations. Good Heavens! how is any one woman to use up all those gowns and cloaks and fine clothes of every denomination? And the profusion of coronets! every stocking, every pockethandkerchief, every thing had a coronet on it! ... Poor Blanche doesn't seem to know, amidst the excitement and rapture of the trousseau, whether she loves the man or not; - she hopes well enough at least for practical purposes. I liked him very much for my share; and wish little Alice had the fellow of him.

But, Oh! how thankful I was to get away, where I might lie in bed, "well let alone," and do out my illness! We found Ann very neat and glad to see us. She is a thoroughly good, respectable woman - the best character I ever had in the house. ...

Kindest love to my dear Uncle and the rest. I have heard nothing of the Sketchleys since the week after you left.

Ever your affectionate

J. W. C.

A. S. [Sterling] has swapt his Yacht for another which he has christened the Mazzini. Mr. C. starts for Paris tomorrow, for a ten days or a fortnight, I suppose.

LETTER 129

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig

Chelsea, Saturday, 'Nov., 1851.'

My dear John - Thanks for your kind attention in sparing me as much as possible all alarm and anxiety. Your two welcome Notes were followed by one from Helen last night, representing my Uncle as in the most prosperous state after his long journey. It was not, however, the immediate consequences that I felt most apprehensive of; and I shall not be quite at ease about him till a few days are well over. Every time I myself have gone a long way by express, the frightful headache produced in me comes on gradually after, and does not reach its ultimatum till some three or four days. They all seem very grateful to you for your kind attention to my Uncle; and so am I; and it is a real pleasure to me to hear them speak of you so warmly.

For the rest, if the Devil had not broken loose on me this morning, it was my intention to have written you a long Letter, - in spite of your preference for short ones. But there are so many things requiring to be done that I must not dawdle over any of them. Mrs. Piper wants me at her house at midday, to inspect the arrangements she has made for the reception of Mazzini, Saffi and Quadri,[1] to whom I have let the three bedrooms and one sitting-room, left empty in the Piper house by the departure of an old lady and Daughter who lived with them (the Mother and Sister, in fact, of L. E. L.[2]); and the Piper economics were in danger of rushing down into "cleanness of teeth," in consequence. So, as Mazzini applied to me for apartments, I brought the two wants to bear on each other, to the great contentment of both parties. I have also lent the Pipers a bedstead, a washstand, and two extremely bad chairs; and must now go and put a few finishing touches from the hand of Genius to her arrangements; and, above all, order in coals and candles, or the poor men will have a wretched home to come to this cold night.

I have got Saffi Italian lessons, - at the Sterlings and Wedgwoods. So now, to use Mazzini's expression, "he is saved." Carlyle is extremely fond of Saffi: I have not seen him take so much to any one this long while.

Besides that piece of business, there are three answers to sorts of business Letters that must be written: one requiring my active exertions in the placing of a - Lady's-maid! (Good Gracious, what things people do ask of one!); one from Lady Ashburton, who has not taken the slightest notice of me, but "quite the contrary," ever since I refused her invitation to the Grange on her return from Paris! This Letter also, is an invitation, - to come on the 1st of December and stay over Christmas, put on the touching footing of requiring my assistance to help "in amusing Mama" [Lady Sandwich]. Heaven knows what is to be said from me individually. If I refuse this time also, she will quarrel with me outright, - that is her way; - and as quarrelling with her would involve quarrelling with Mr. C. also, it is not a thing to be done lightly. - I wish I knew what to answer for the best.[1]

I have also to write to Mrs. Macready this day for a copy of the Sterling which I lent her to take with her to Sherborne; it is Mr. C.'s own copy and has pencil corrections on it, and is now wanted for the new Edition which Chapman is here at this moment negotiating for. None of Mr. C.'s Books have sold with such rapidity as this one. If he would write a Novel we should become as rich as - Dickens! "And what should we do then?" "Dee and do nocht ava!" I don't think it would be any gain to be rich. I should then have to keep more servants, - and one is bad enough to manage. Ann, however, goes on very peaceably, except that in these foggy, dispiriting mornings she is often dreadfully low about her wrist. I have given her a pair of woollen wristikins. Can I do anything more? Young Ann I have got to be housemaid with Lady Lytton, who has taken a cottage all to herself. ...

Love to your Mother and the rest of you.

Affectionately,

J. W. C.

LETTER 130

To Mrs. Russell, Thornhill.

Chelsea, Tuesday, '6 Jan'y, 1852'.

My dear Mrs. Russell - Here I am at home again[1] - to the unspeakable joy of - my dog, if no one else's. I assure you the reception he gave us left the heart nothing to wish. I found a clean house, with nothing spoilt or broken. My present servant, who has lasted since last May, is a punctual trustworthy woman; very like our Haddington Betty in appearance. I hope she will stay - forever, - if that were possible. ...

I hope you will now write me a long Letter about dear old Thornhill, and all the people I know there. I send the Order for the money, which I need not doubt but you advanced for me. I hoped by this time to have had a Book to send you, Mr. C.'s Life of Sterling, of which a second edition is now printing; but it is not ready yet, so you must wait a little longer.

Only imagine my three Aunts coming up to the Exhibition last August! I should have thought it much too worldly a subject of interest for them. I had gone to Malvern only two days before they arrived, - so missed them altogether.

Love to your Husband and Father.

Ever affectionately yours,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 131

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, '27 July, 1852.'

My dear John - You will like to hear "what I am thinking of Life" in the present confusion. Well, then, I am not thinking of it at all but living it very contentedly. The tumult has been even greater since Mr. C.[1] went than it was before; for new floors are being put down in the top story, and the noise of that is something terrific. But now that I feel the noise and dirt and disorder with my own senses, and not through his as well, it is amazing how little I care about it. Nay, in superintending all these men I begin to find myself "in the career open to my particular talents," and am infinitely more satisfied than I was in talking "wits," in my white silk gown with white feathers in my head, and soirées at Bath House, "and all that sort of thing." It is a consolation to be of some use, tho' it were only in helping stupid carpenters and bricklayers out of their "impossibilities," and, at all rates, keeping them to their work; especially when the ornamental no longer succeeds with me so well as it has done! The fact is, I am remarkably indifferent to material annoyances, considering my morbid sensibility to moral ones. And when Mr. C. is not here recognising it with his overwhelming eloquence, I can regard the present earthquake as something almost laughable.

Another house-wife trial of temper has come upon me since Mr. C. went, of which he yet knows nothing, and which has been borne with the same imperturbability: He told you, perhaps, that I had got a new servant in the midst of this mess, - a great beauty, whom I engaged because she had been six years in her last place, and because he decidedly liked her physiognomy. She came home the night before he left. It was a rough establishment to come into, and no fair field for shewing at once her capabilities; but her dispositions were perhaps on that account the more quickly ascertained. The first night I came upon her listening at the door; and the second morning I came upon her reading one of my Letters! And in every little box, drawer and corner I found traces of her prying. It was going to be like living under an Austrian Spy. Then, because she had no regular work possible to do, she did nothing of her own accord that was required. Little Martha, who was here in Ann's illness and whom I had taken back for a week or two, was worth a dozen of her in serviceableness. The little cooking I needed, was always "what she hadn't been used to where she lived before," and for that, or some other reason, detestable. I saw before the first week was out, that I had got a helpless, illtrained, low-minded goose; and this morning, the last day of the week, I was wishing to Heaven I had brought no regular servant into the house at all just now, but gone on with little Martha, As there was not work enough for half a one, never to speak of two, I had told little Martha she must go home to-night. I would rather have sent away the other, but she had waited three weeks for the place, and couldn't be dispatched without a week's warning; and besides, I felt hardly justified in giving her no longer trial. Figure my satisfaction, then, when on my return from taking Mazzini to call for the Brownings, the new servant came to me, with a set face, and said, "she had now been here a week and found the place didn't suit her; if it had been all straight, perhaps she could have lived in it; but it was such a muddle, and would be such a muddle for months to come, that she thought it best to get out of it." I told her I was quite of her opinion, and received the news with such amiability that she became quite amiable, too, and asked "when would I like her to go." "To-night," I said; "Martha was to have gone to-night, now you will go in her stead, and that will be all the difference!" And she is gone, bag and baggage! We parted with mutual civilities, and I never was more thankful for a small mercy in my life. And the most amusing part of the business is, that although taken thus by surprise I had before she left the house, - engaged another servant! By the strangest chance, Irish Fanny, who has always kept on coming to see me from time to time, and is now in better health, arrived at tea-time to tell me she had left her place. I offered her mine, which she had already made trial of, and she accepted with an enthusiasm which did one's heart good after all those cold, ungrateful English wretches. I stipulated, however, that she should not come for a month, little Martha being the suitablest in the present state of the family. Little Martha is gone to bed the happiest child in Chelsea, at the honour done her. "I could have told you, Ma'am," she said, "the very first day that girl was here, that she wasn't fit for a genteel place; and I'm sure she isn't so much older than me as she says she is!"

Oh, such a fuss the Brownings made over Mazzini this day! My private opinion of Browning is, in spite of Mr. C.'s favour for him, that he is "nothing," or very little more, "but a fluff of feathers!"[1] She is true and good, and the most womanly creature.

I go to Sherborne on Friday to stay till Monday. It is a long, fatiguing journey for so short a time, and will be a sad visit; but she[1] wishes it. And now, good-night.

With kind regards to all.

Affectionately yours,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

LETTER 132

To T. Carlyle, Linlathen, Dundee.

Chelsea, Tuesday, 3 August, 1852.

Oh, my Dear, if I had but a pen that would mark freely - never to say spell - and if I might be dispensed from news of the house, I would write you such a Lettre d'une voyageuse as you have not read "these seven years!" For it was not a commonplace journey this at all; it was more like the journey of a Belinda or Evelina or Cecilia: your friends "The Destinies," "Immortal gods," or whatever one should call them, transported me into the Region of mild Romance for that one day. But with this cursed house to be told about, and so little leisure for telling anything, my Miss Burney faculty cannot spread its wings. So I will leave my journey to Sherborne for a more favourable moment, - telling you only that I am no worse for it; rather better, if indeed I needed any bettering, which it would be rather ungrateful to Providence to say I did. Except that I sleep less than ordinary mortals do, I have nothing earthly to complain of - nor have had since you left me. Nor will I even tell you of the Macreadys in this Letter. I cannot mix up the image of that dear dying woman with details about bricklayers and carpenters. You ask what my prophetic gift says to it, which is more to be depended on than Mr. Morgan's calculations. My Dear, my prophetic gift says very decidedly that it will be two months at least before we get these fearful creatures we have conjured up laid. The confusion at this moment is more horrible than when you went away. The Library is - exactly as you left it! The plasterers could not commence there on account of the moving of the floors above; and the front bedroom floor could not be got on with on account of the pulling down of the chimney; your bedroom is floored, and has got its window-shutters; and the painter was to have begun there on Saturday, and has not appeared yet; and Mr. Morgan keeps away, and I am nearly mad. My present bedroom is as you left it, - only more full of things. The chimney above, up-stairs, is carried back and finished; the floor is still up there and the ceiling down; it will be a week before they get the floor laid there; and till then plastering can't be begun with below!!

... And now you must consider and decide. For two months I am pretty sure there will be no living for you here. I can do quite well; and seem to be extremely necessary for shifting about the things, and looking after the men. The only servant in the house is little Martha. Our Beauty was as perfect a fool as the sun ever shone on, and at the end of a week left, finding it "quite impossible to live in any such muddle." I have been doing very well with Martha for the last week; and Irish Fanny is engaged to come on the 27th; but I did not want a regular servant at present. My idea is that you ought to go to Germany by yourself, leaving me here, where I am more useful at present than I could be anywhere else. But if you don't like that, there will be the Grange open for September, and you could go by yourself there. As to "cowering into some hole," you are "the last man in all England" that can do that sort of thing with advantage; so there's no use speculating about it.

If you could make up your mind to Germany any easier for my going to see to the beds, etc., of course there is no such absolute need of my staying here, that I should not delegate my superintendence to Chalmers or somebody, and put Fanny into the kitchen, and go away; - but I don't take it the least unkind your leaving me behind; and with Neuberg to attend on you, I really think you would be better without me.

Ever yours,

J. W. C.

Love to Mr. Erskine, and thanks for his Note.

LETTER 133

To T. Carlyle, Linlathen, Dundee.

Chelsea, Friday, '6 Aug., 1852.'

As to Nero, poor darling, it is not forgetfulness of him that has kept me silent on his subject, but rather that he is part and parcel of myself: when I say I am well, it means also Nero is well! Nero c'est moi; moi c'est Nero! I might have told something of him, however, rather curious. Going down in the kitchen the morning after my return from Sherborne I spoke to the white cat, in common politeness, and even stroked her; whereon the jealousy of Nero rose to a pitch! He snapped and barked at me, then flew at the cat quite savage. I "felt it my duty" to box his ears. He stood a moment as if taking his resolution; then rushed up the kitchen stairs; and, as it afterward appeared, out of the house! For, in ten minutes or so, a woman came to the front door with master Nero in her arms; and said she had met him running up Cook's Grounds, and was afraid he "would go and lose himself!" He would take no notice of me for several hours after! And yet he had never read "George-Sand Novels," that dog, or any sort of Novels!

But of Germany: I really would advise you to go, - not so much for the good of doing it, but for the good of having done it. Neuberg is as suitable a guide and companion as poor humanity, imperfect at best, could well afford you. And I also vote for leaving me out of the question. It would be anything but a pleasure for me to be there, with the notion of a house all at sixes and sevens to come home to. ... You will take me there another time if you think it worth my seeing. Or I could go some time myself and visit Bölte; or I can have money to make any little journey I may fancy, - some time when I am out of sorts, - which I am not now, thanks God, the least in the world. If it were not for the thought of your bother in being kept out of your own house, I should not even fret over the slowness of the house-altering process. I can see that there is an immense deal of that sort of invisible work expended on it which you expended on Cromwell. The two carpenters are not quick, certainly, but they are very conscientious and assiduous, giving themselves a great deal of work that makes no show, but which you should be the last man to count unnecessary. ... When it comes to putting everything in order again, it will be a much greater pleasure than going to Germany, I can tell you. - I had plenty of other things to tell; but when one gets on that house there is no end of it. ... But Oh, heavens! there is twelve striking.

Ever yours,

J. W. C.

LETTER 134

To T. Carlyle, care of Joseph Neuberg, Bonn.

Chelsea, Thursday, 2 Sep., 1852.

... I have a new invitation to go to Addiscombe to-morrow, Friday, and stay till Monday (Lord Ashburton being gone to Scotland "quite promiscuously," and her Ladyship in consequence going a second time to Addiscombe). I accepted; being very anxious to have a Christian bed for a night or two, having alternated for a week betwixt the sofa in this room, and the bed at 2 Cheyne Walk, - on the same principle that Darwin frequents two clubs. ... Last night Lady A. sent me word by Fanny, who had taken her up the cranberry jam promised long ago, that it was possible she might not go till Saturday.

I dined with Forster on Tuesday, "fish and pudding"; and the Talfours and Brownings came to early tea. The Brownings brought me in their cab to Piccadilly and put me in an omnibus. It was a very dull thing indeed; and I like Browning less and less; and even she does not grow on me. Mrs. Sketchley, after reading your Note for her,[1] held out her hand to me and - burst into tears! and Penelope fell a-crying at seeing her Mother crying, - without knowing why! "Whatever comes of it, - if nothing comes of it," said the old lady, "that is kindness never to be forgotten."

Ever yours affectionately,

JANE CARLYLE.

P. S. - I hope John's love affair will get on.

LETTER 135

To Dr. Carlyle, Scotsbrig.

Chelsea, Monday, 'Sep., 1852.'

My dear John - ... Mrs. Macready is at Plymouth, Forster told me yesterday; stood the journey better than was anticipated; but the Doctor there gives no hopes of her. Oh no! one has only to look at her to feel that there is no hope.

I wonder now if you will break down in that enterprise? Please don't. I want very much to see you comfortably settled in life; and with a woman of that age, whom you have known for fifteen years, I should not feel any apprehensions about your doing well together.[2] But you put so little emphasis into your love-making, that it won't surprise me if this one, too, get out of patience and slip away from you!

Your affectionate

J. W. C.

LETTER 136

To Dr. Carlyle, Burnbraes, Moffat.

Chelsea, 15 September, 1852.

My dear John - ... Thanks God, however, the workmen are gradually "returning from the Thirty-years' War." My plasterers and plumbers are gone; and my bricklayers and carpenters going; and I have now only painting and paperhanging to endure for a week or two longer. ...

Meantime the Duke of Wellington is dead. I shall not meet him at Balls any more, nor kiss his shoulder, poor old man. All the news I have had from the outer world this week is sad. ...

"Like Mrs. Newton"[1] - that is charming! When shall I see her? It is really very pleasant to me, the idea of a new Sister-in-law! What on earth puts it in people's heads to call me formidable? There is not a creature alive that is more unwilling to hurt the feelings of others, and I grow more compatible every year that I live. I can't count the people who have said to me first and last, "I was so afraid of you! I had been told you were so sarcastic!" And really I am perfectly unconscious of dealing in that sort of thing at all. ... So depend on it the Ba-ing will be agreeably disappointed when we meet.

But now I should be in bed. Nero is already loudly snoring on a chair. Good-night.

Yours affectionately,

JANE W. CARLYLE.

Mrs. Carlyle's Love Story.

In November, 1852, Mrs. Carlyle wrote a short Story in the form of an "Imaginary Letter," in a little Note-Book which Carlyle has labelled "Child Love." Mr. Froude in his Life of Carlyle (i., 285), has printed the opening sentences of the Preface to the Story thus:

"What 'the greatest Philosopher of our day' execrates loudest in Thackeray's new Novel - finds indeed 'altogether false and damnable in it' - is that love is represented as spreading itself over our whole existence, and constituting one of the grand interests of it; whereas love - the thing people call love - is confined to a very few years of man's life; to, in fact, a quite insignificant fraction of it, and even then is but one thing to be attended to among many infinitely more important things. Indeed, so far as he (Mr. C.) has seen into it, the whole concern of love is such a beggarly futility, that in an heroic age of the world nobody would be at the pains to think of it, much less to open his mouth upon it."

Mr. Froude's deduction from this is: "A person who had known by experience the thing called love, would scarcely have addressed such a vehemently unfavourable opinion of its nature to the woman who had been the object of his affection."

What Carlyle meant by "the thing people call love" will be best made manifest by the Story itself. Possibly Mr. Froude's reason for omitting the Story may have been that he feared it might suggest to shrewd readers the absurdity of the Irving Episode in his account of Carlyle's life. Irving gave lessons to Miss Welsh from October, 1811 to August, 1812. She was ten years and three months old when he began to instruct her; and eleven years, one month and some few days old when he left Haddington.

After the citation made by Mr. Froude, Mrs. Carlyle gives instances amongst her own acquaintances of people being "in love" at all ages from six to eighty-two; and then tells in the following graphic and amusing way:

"THE SIMPLE STORY OF MY OWN FIRST-LOVE."

Well, then, I was somewhat more advanced in life than the child in the aforesaid Breach-of-promise case, when I fell in love for the first time. In fact I had completed my ninth year; or, as I phrased it, was "going ten." One night, at a Dancing-school Ball, a stranger Boy put a slight on me which I resented to my finger ends; and out of that tumult of hurt vanity sprang my First-love to life, like Venus out of the froth of the sea!! - So that my First-love resembled my Last, in that it began in quasi-hatred.

Curious, that, recalling so many particulars, of this old story, as vividly as if I had it under my opera-glass, I should have nevertheless quite forgot the Boy's first name! His surname, or as the Parson of St. Mark's would say, "his name by nature," was Scholey, - a name which, whether bestowed by nature or art, I have never fallen in with since; but the Charles, or Arthur, or whatever it was that preceded it, couldn't have left less trace of itself had it been written in the "New Permanent Marking-ink!" He was an only child, this Boy, of an Artillery Officer at the Barracks, and was seen by me then for the first time; a Boy of twelve, or perhaps thirteen, tall for his years and very slight, - with sunshiny hair, and dark-blue eyes; a dark-blue ribbon about his neck; and grey jacket with silver buttons. Such the image that "stamped itself on my soul forever!" - And I have gone and forgotten his name!

Nor were his the only details which impressed me at that Ball. If you would like to know my own Ball-dress, I can tell you every item of it: a white Indian muslin frock open behind, and trimmed with twelve rows of satin ribbon; a broad white satin sash reaching to my heels; little white kid shoes, and embroidered silk stockings, - which last are in a box up-stairs along with the cap I was christened in! my poor Mother having preserved both in lavender up to the day of her death.

Thus elegantly attired, and with my "magnificent eye-lashes" (I never know what became of these eye-lashes) and my dancing "unsurpassed in private life" (so our dancing-master described it), - with all that and much more to make me "one and somewhat" in my own eyes, what did I not feel of astonishment, rage, desire of vengeance, when this Boy, whom all were remarking the beauty of, told by his Mama (I heard her with my own ears) to ask little Miss Welsh for a quadrille, declined kurt und gut, and led up another girl, - a girl that I was "worth a million of," if you'll believe me, - a fair, fat, sheep-looking thing, with next to no sense; and her dancing! you should have seen it! Our dancing-master was always shaking his head at her, and saying "heavy, heavy!" - But her wax-doll face took the fancy of Boys at that period, as afterwards it was the rage with men, till her head, unsteady from the first discovery of her, got fairly turned with admiration, and she ended in a mad-house, that girl! Ah! had I seen by Second-sight at the Ball there, the ghastly doom ahead of her, - only some dozen years ahead, - could I have had the heart to grudge her one triumph over me, or any partner she could get? But no foreshadow of the future Madhouse rested on her and me that glancing evening, tho' one of us, - and I don't mean her, was feeling rather mad. No! never had I been so outraged in my short life! never so enraged at a Boy! I could have given a guinea, if I had had one, that he would yet ask me to dance, that I might have said him such a No! But he didn't ask me; neither that night nor any other night; indeed, to tell the plain truth, if my "magnificent eyelashes," my dancing "unsurpassed in private life," my manifold fascinations, personal and spiritual, were ever so much as noticed by that Boy, he remained from first to last, impracticable to them!

For six or eight months, I was constantly meeting him at children's Balls and Tea-parties; we danced in the same dance, played in the same games, and "knew each other to speak to"; but the fat Girl was always present, and always preferred. They followed one another about, he and she, "took one another's parts," kissed one another at forfeits, and so on; while I, slighted, superfluous, incomprise, stood amazed as in presence of the infinite! But that was only for a time or two while I found myself in a "new position;" a little used to the position, I made the best of it. After all, wasn't the fat Girl two years older than I? and that made such a difference! Had I been eleven "going twelve," - I with my long eyelashes, lovely dancing, etc., things would have gone very differently, I thought, - decidedly they would. So "laying the flattering unction to my soul," I gradually left off being furious at the Boy, and rejoiced to be in his company on any footing.

Next to seeing the Boy's self, I liked making little calls on his Mother; but how the first call, which was the difficulty, got made, I have only a half remembrance; or rather I remember it two different ways! - a form of forgetfulness not uncommon with me. I should say quite confidently, that I first found myself in Mrs. Scholey's Barracks at her own urgent solicitation, once when she had lighted on me alone at "the evening Band," if it were not for my clear recollection of being there the first time with my governess, who, of "military extraction" herself (she boasted her Father had been a serjeant in the militia), was extensively liée at the Barracks. At all events my Mother was on no visiting terms with this lady; and it is incredible I should have introduced myself on my own basis. Very likely she had besieged me to visit her; for the ladies at the Barracks were always manoeuvring to get acquainted in the Town. And just as likely my governess had taken me to her; for my governess had a natural aptitude for false steps. In either case, the ice once broken, I made visits enough at Mrs. Scholey's Barracks, where I was treated with all possible respect. Still as a woman Mrs. Scholey didn't please me, I remember; inasmuch as she was both forward and vulgar; and it wasn't without a sense of demeaning myself, that I held these charmed sittings in her Barracks. But then, it wasn't the woman that I visited in her; it was the Boy's Mother; and in that character she was a sort of military Holy Mother for me, and her Barracks looked a sacred shrine! Then, so often as she spoke to me of her Son, and she spoke I think of little else, it was in a way to leave no doubt in my mind, that the first wish of her (Mrs. Scholey's) heart was to see him and me ultimately united; and there is no expressing how it soothed me under the confirmed indifference of the Son to feel myself so appreciated by his Mother. Nor was Mrs. Scholey herself my sole attraction to that Barracks: the Boy, be it clearly understood, I never saw there, or assuredly I should have made myself scarce. God forbid that at even nine years of age I should have had so little sense, - not to say spirit, - as to be throwing myself in the way of a Boy who wanted nothing with me! Oh no, the Boy was all day at School in the Town, within a gun-shot of my own door, - a quarter of a mile at least nearer me than his Mother. For the other attraction the Barrack room possessed for me, it was a Portrait, - nothing more nor less, - a dear little oval Miniature of the Boy in petticoats; done for him in his second or third year; and so like, I thought, - making allowance for the greater chubbiness of babyhood, and the little pink frock, of no sex. At each visit I drank in this "Portrait charmant" with my eyes, and wished myself artist enough to copy it. Indeed had one of the Fairies I delighted to read of stept out of the Book, in a moment of enthusiasm, to grant any one thing I asked, I would have said, I am sure I would, "the Portrait charmant, then, since you are so good, all to myself for altogether!"

Still, I hadn't as yet, to the best of my remembrance, admitted to myself (to others it would have been impossible) that I was head and ears in love. Indeed an admission so entirely discreditable to me couldn't be too long suppressed. Oh, little Miss Welsh! at your time of age and with your advantages, to go and fall in love with an Artillery Boy, and he not caring a pin for you! It was really very shocking, very. And let us hope, I should have felt all that was proper on the discovery of my infatuation, if the circumstances under which it was made had been less poignant! The Boy's Regiment had received orders to march! To Ireland, I think it was; but the where was nothing. For me, in my then geographical blankness, the marching beyond my own sphere of vision was a marching into infinite space! Lo! Two more days and the Boy, his Mother, his Regiment and all that was his, would be in infinite space for me! Here was a prospect to enlighten one on the state of one's heart, if anything could! Now I knew all I had felt for him and all I felt; and I forgave him all about the fat Girl; and believed in the "Progress of the Species."[1]

Had I stopt there, well and good; but a sudden thought struck me, a project of consolation so subversive of "female delicacy," that I almost blush to write it! But in these moments termed "supreme," one "swallows all formulas" as fast as look at them, - at least I do. This project, then? Could it be the confession of my love to its object, you may be thinking? Almighty Gracious! no, not that!! Though with no knowledge as yet of what my American young lady called "Life," instinct divined all the helplessness of that shift, even could I have gulped the indecency of it. No! My project was flagrantly compromising, and something might be gained by it. It was this simply: To persuade Mrs. Scholey to leave the little oval Miniature with me, on loan, on the understanding that when I was grown up and should have money, I would return it to her, set with diamonds; and as an immediate tribute of gratitude, or pure esteem, - whichever she liked, - I would present her with my gold filigree needle-case, the only really valuable thing I possessed, - and sent from India all the way! But it might go, without a sigh, in part payment of such a favour! Whether my idea was, that "grown up" and "having money," I should procure a copy of the Miniature for myself, besides the diamonds for Mrs. Scholey, or whether it was that I should have another attachment by then, and that Portrait be fallen obsolete, chi sa? One can't remember everything, even in remembering much. Only so far as the actual crisis was concerned, my project and its results have left a picture in my mind as distinct as that Descent from the Cross hanging on the opposite wall.

It was not without misgivings enough that I entered on this questionable enterprise. I felt its questionability in every fibre of my small frame. But what then? The day after to-morrow the Boy's self would be in infinite space for me; and if I had not his picture to comfort me, how on earth should I be comforted? So I took a great heart, prayed to Minerva, I remember. I had got converted to Paganism in the course of learning Latin, and Minerva was my chosen goddess. And in the first interval of lessons, I ran off to the Artillery Barracks, taking the gold needle-case in my hand; and never had it looked so pretty! Mrs. Scholey was at home packing up (ah me!), and the Miniature was in its old place. I had been so afraid of it being packed up, that the mere seeing it seemed a step in getting it. There it hung, by its black ribbon, from a nail over the fireplace; and, "didn't I wish I might get it?" If only I might have walked off with it without a word! But I was come to beg, not steal, good God; and "to beg I was ashamed!" My program had been to throw myself on Mrs. Scholey's generosity for the picture; and then to slip my needle-case into her hand. But face to face with the lady, something warned me to offer her the needle-case first, and throw myself on her generosity after. Still how to unfold my business even in that order? My position became every moment more false; I sat with burning cheeks and palpitating heart, - my tongue refusing "its office" save on indifferent topics, till I felt that in common decency I could sit no longer. And then only, - in the supreme moment of bidding Mrs. Scholey farewell, - did I find courage to present my needle-case, - with what words I know not; but certainly without one word about the picture. For the rapid acceptance of my really handsome gift, as a "good the gods had provided her," and no more about it, quite took away my remaining breath, and next minute I found myself in the open air, "a sadder and a wiser child!"

At three o'clock the following morning, the Boy's Regiment marched, with Band playing gaily "The Girl I've left behind me." Soundly as I slept in those years, I could not sleep through that; and sitting up in my little bed to catch the last note, it struck me I was the Girl left behind, little as people suspected it! - For a day or two I felt quite lost, and was "not myself again" for weeks. Still at nine years of age, so many consolations turn up, and one is so shamefully willing to be consoled!

For the rest, young Scholey (I wish I could have recollected his first name!) had slipt through my fingers like a knotless thread: he never came back to learn our fates (the fat Girl's and mine), nor did news of him dead or alive ever reach me. And so, in no great length of time, - before I had given him a successor even, - he passed for me into a sort of myth; nor for a quarter of a century had I thought as much of him, put it altogether, as I have done in writing these few sheets.