NEGRO MUSICIANS

AND THEIR MUSIC

BY

MAUD CUNEY-HARE

THE ASSOCIATED PUBLISHERS, INC.

WASHINGTON, D. C.

COPYRIGHT, 1936

THE

ASSOCIATED

PUBLISHERS,

INC.

TO

WILLIAM

HOWARD

RICHARDSON

BARITONE

IN

REMEMBRANCE OF

TWENTY

HAPPY

YEARS OF

MUSICAL

PARTNERSHIP

NEGRO MUSICIANS AND THEIR MUSIC

BY

MAUD

CUNEY-HARE

PREFACE

In offering this study of Negro music, I do so with the

admission that there is no consistent development as found

in national schools of music. The Negro, a musical

force, through his own distinct racial characteristics has

made an artistic contribution which is racial but not yet

national. Rather has the influence of musical stylistic

traits termed Negro, spread over many nations wherever

the colonies of the New World have become homes of

Negro people. These expressions in melody and rhythm

have been a compelling force in American music — tragic

and joyful in emotion, pathetic and ludicrous in melody,

primitive and barbaric in rhythm. The welding of these

expressions has brought about a harmonic effect which

is now influencing thoughtful musicians throughout the

world. At present there is evidenced a new movement far

from academic, which plays an important technical part

in the music of this and other lands.

The question as to whether there exists a pure Negro

art in America is warmly debated. Many Negroes as well

as Anglo-Americans admit that the so-called American

Negro is no longer an African Negro. Apart from the

fusion of blood he has for centuries been moved by the

same stimuli which have affected all citizens of the United

States. They argue rightly that he is a product of a vital

American civilization with all its daring, its progress, its

ruthlessness, and unlovely speed. As an integral part of

the nation, the Negro is influenced by like social environment and governed by the same political institutions; thus

we may expect the ultimate result of his musical endeavors

to be an art-music which embodies national characteristics

exercised upon by his soul's expression.

In the field of composition, the early sporadic efforts by

people of African descent, while not without historic importance, have been succeeded by contributions from

a rising group of talented composers of color who are

beginning to find a listening public. The tendency of this

music is toward the development of an American symphonic, operatic and ballet school led for the moment by a

few lone Negro musicians of vision and high ideals.

The story of those working toward this end is herein

treated.

Facts for this volume have been obtained from educated

African scholars with whom the author sought acquaintanceship and from printed sources found in the Boston

Public Library, the New York Public Library and the

Music Division of the Library of Congress. The author

has also had access to rare collections and private libraries

which include her own. Folk material has been gathered

in personal travel.

The author is happy to acknowledge her indebtedness to

the following: To the Boston Museum of Fine Arts for

reproduction of the picture of seventh century musician of

East India, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New

York City for permission to describe African instruments

included in the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments in the Museum, to the Crisis for permission to

reprint poems from that monthly, and to Clarence Cameron White for assistance in reading the proof.

MAUD

CUNEY-

HARE

"Sunnyside"

Squantum, Massachusetts.

January 20, 1936.

CONTENTS*

ILLUSTRATIONS*

| [1st edition, 1936]

| Between Pages

|

| The African Dance

| 16-17

|

| An African Painting

| 16-17

|

| African Musical Instruments

| 19-20

|

| Marimba or Xylophone

| 24-25

|

| African Drums

| 31-32

|

| Fisk Jubilee Singers

| 54-55

|

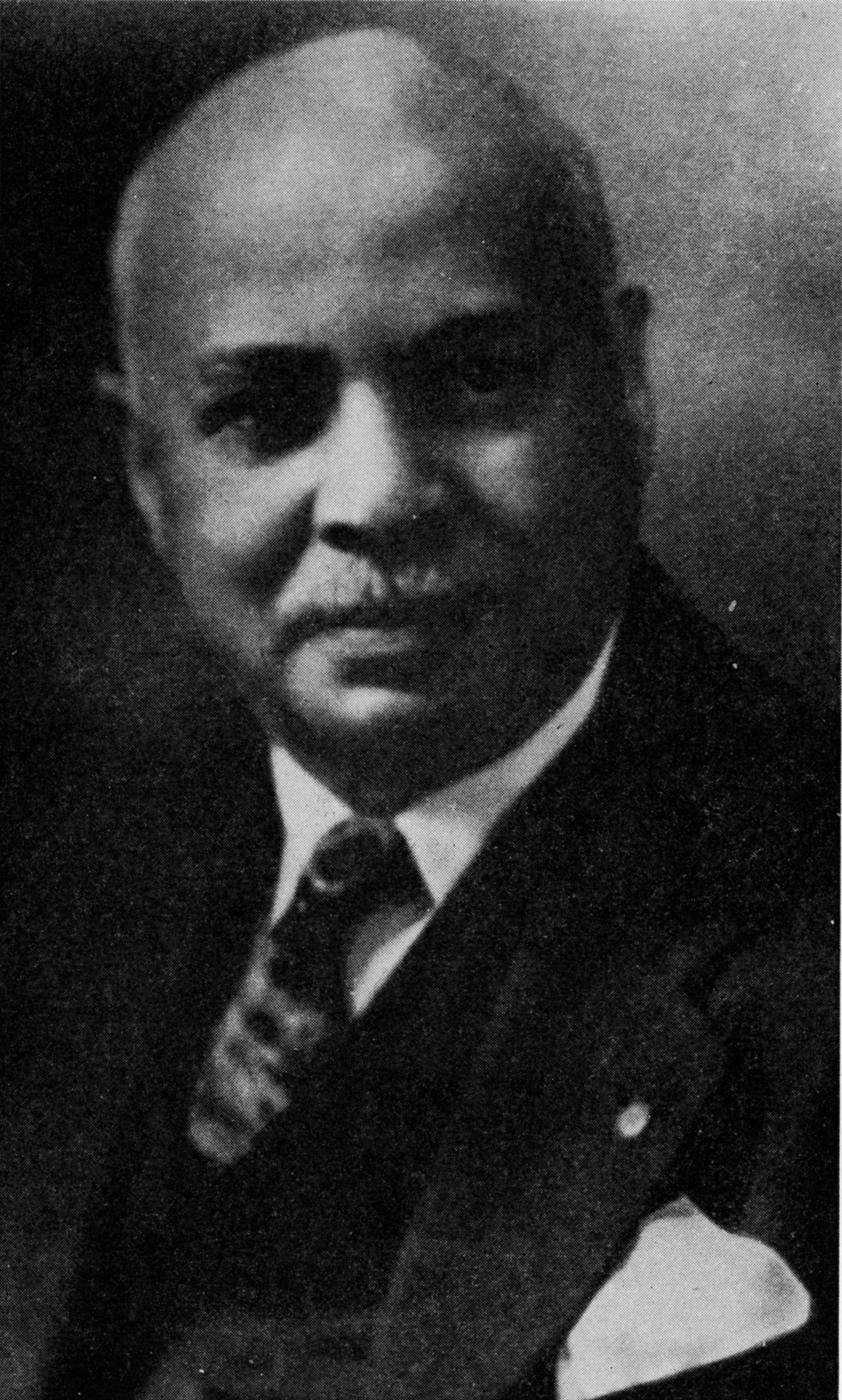

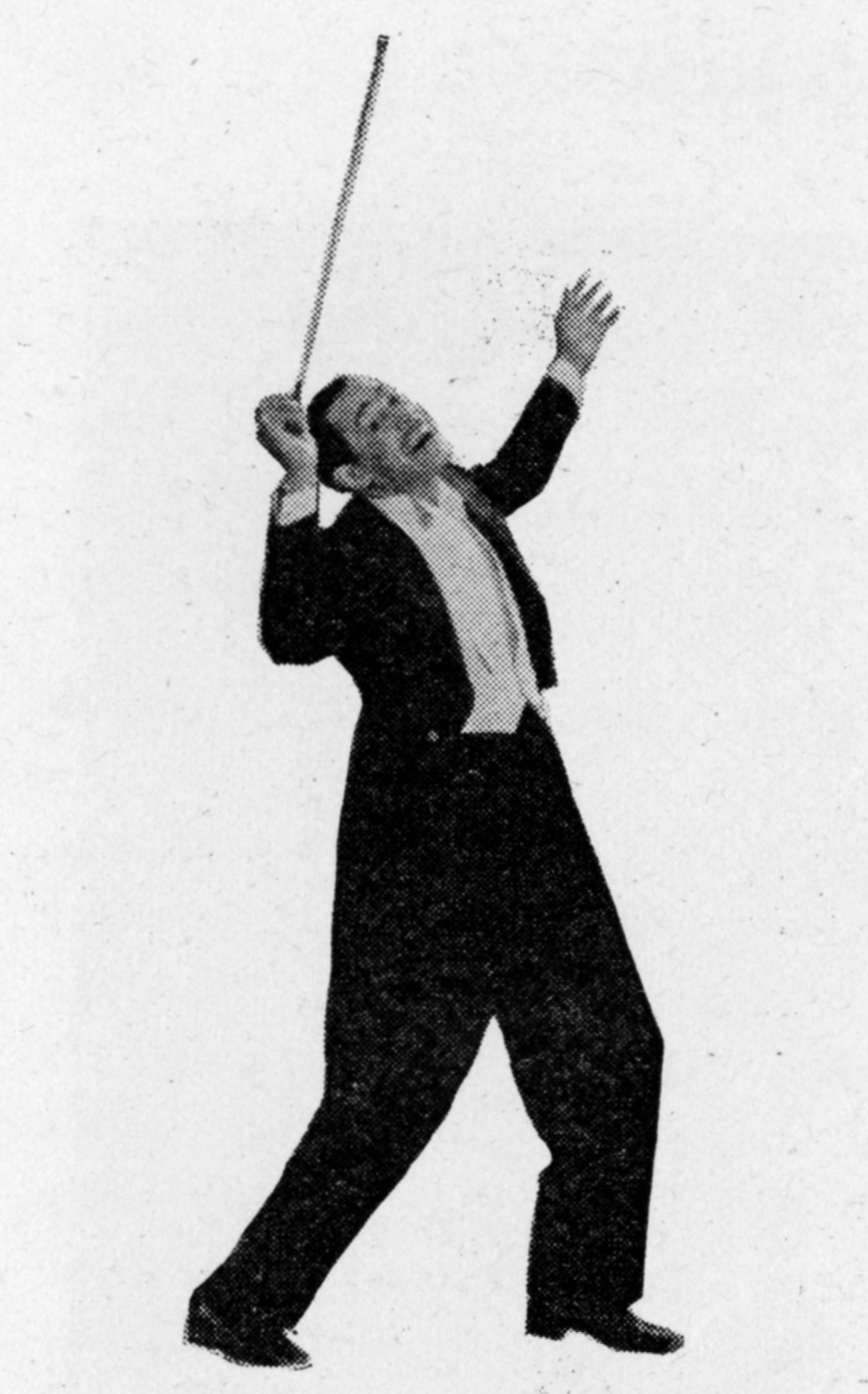

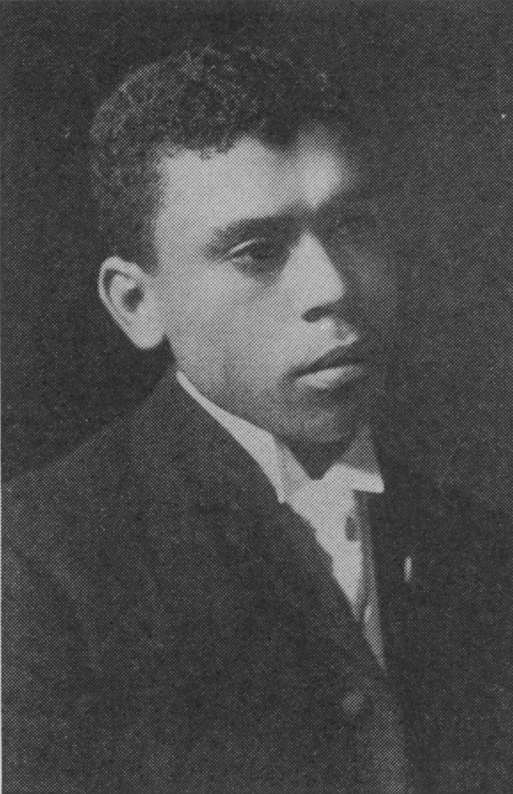

| Will Marion Cook

| 147-148

|

|

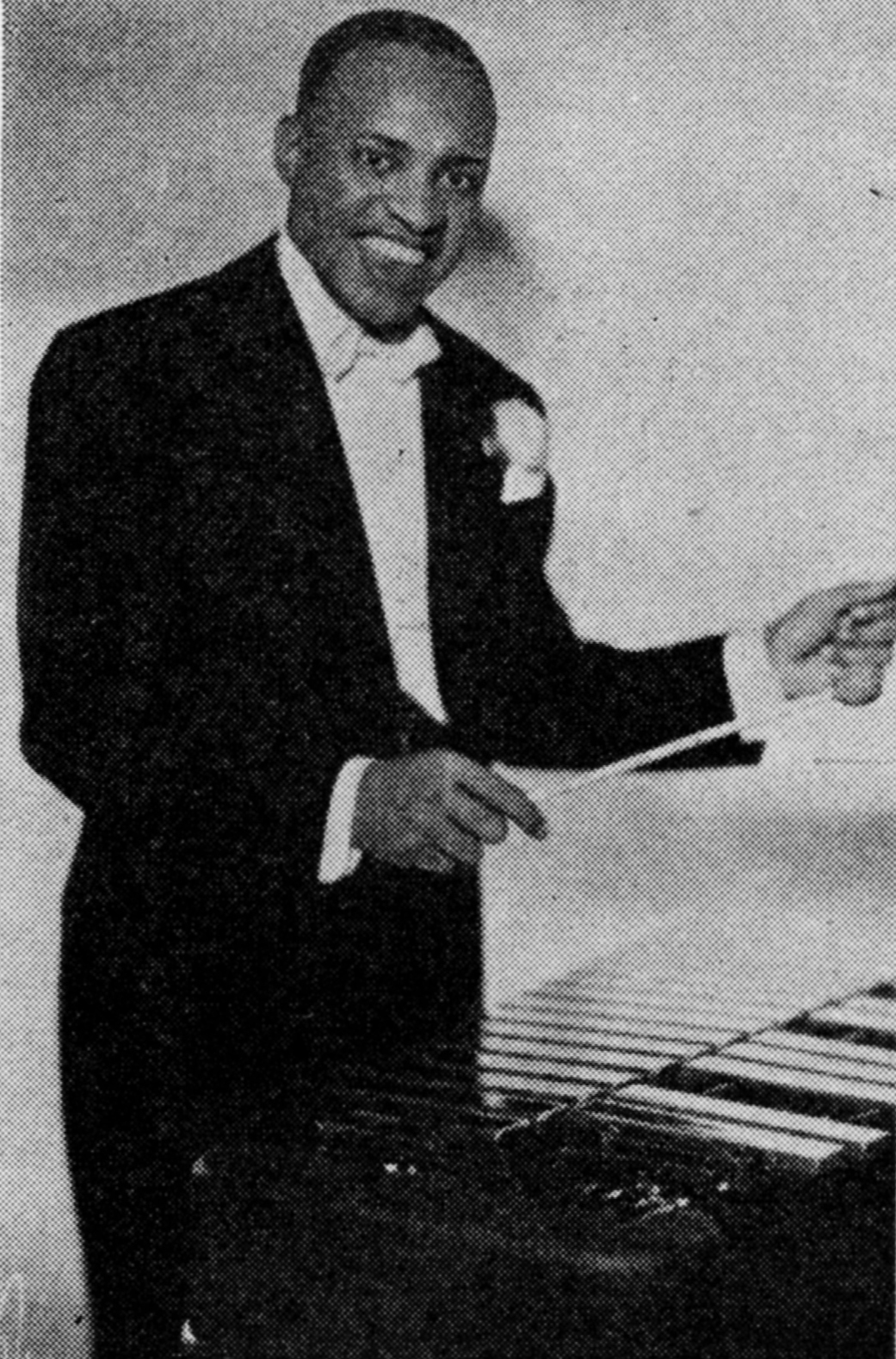

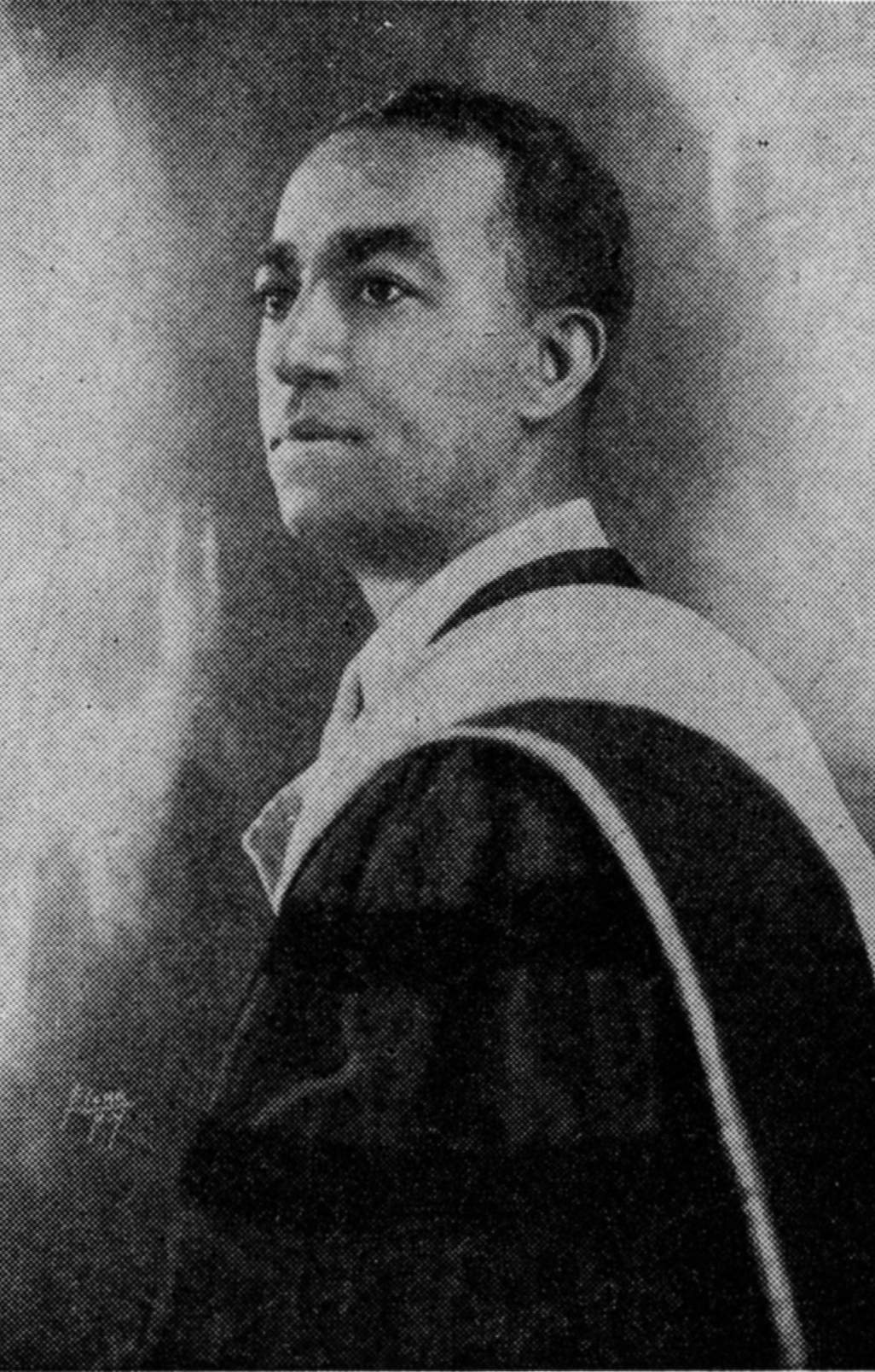

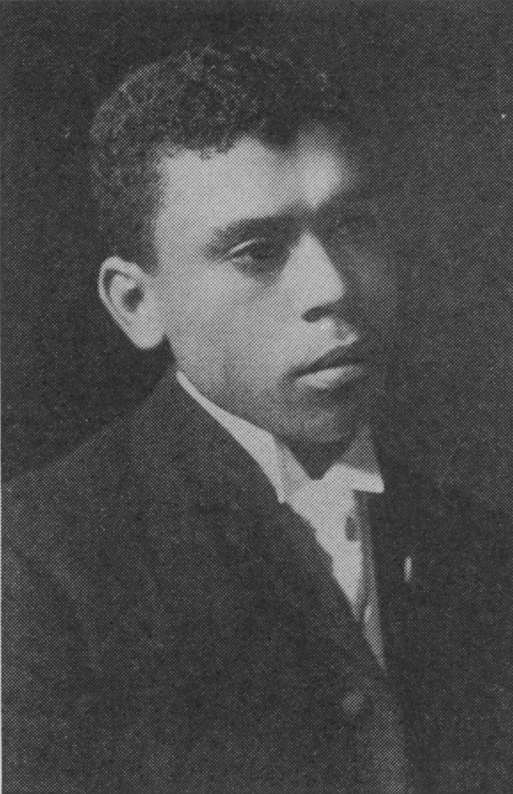

Melville Charlton,

James Reese Europe,

W. L. Dawson, and

Basile Barres

| 155-156

|

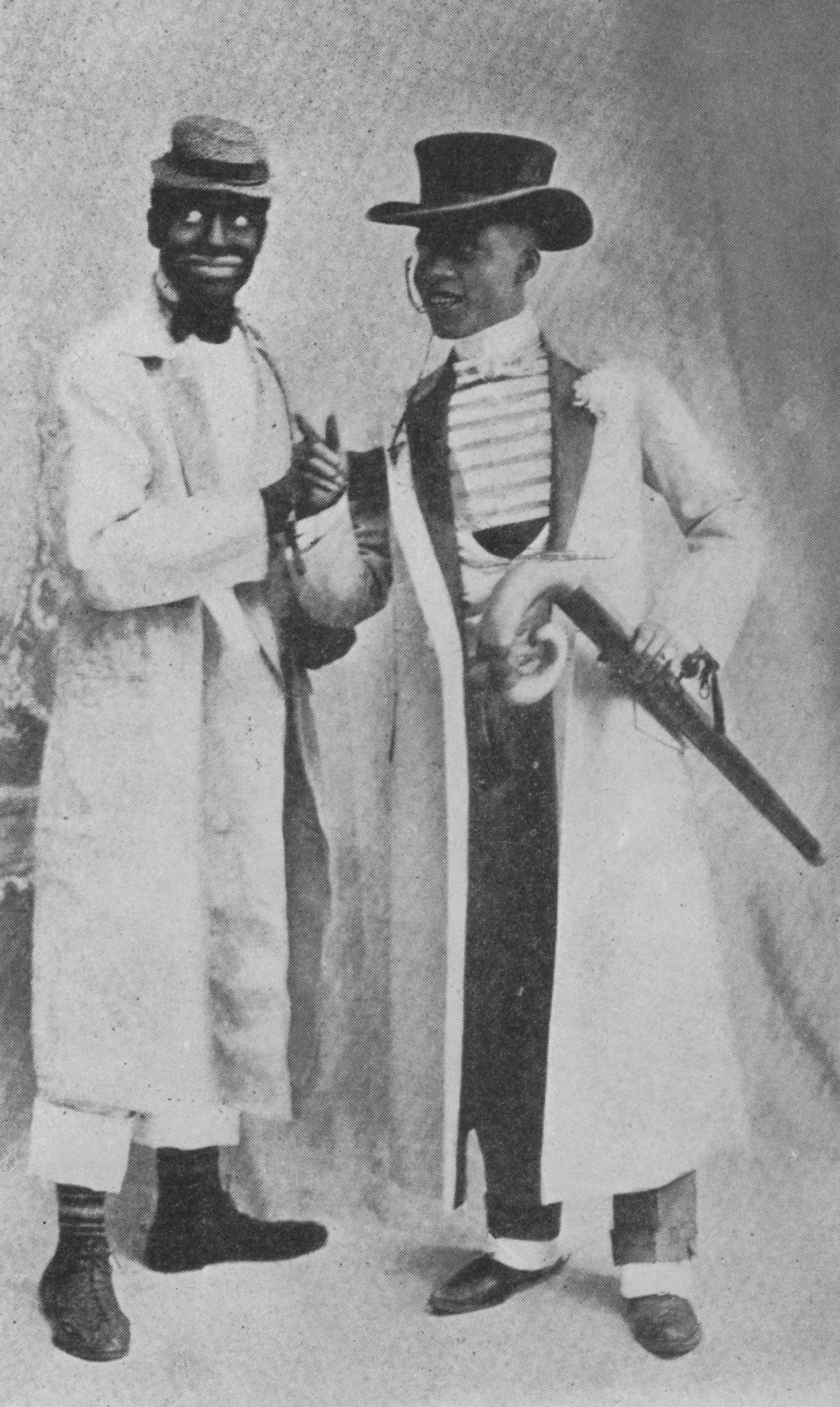

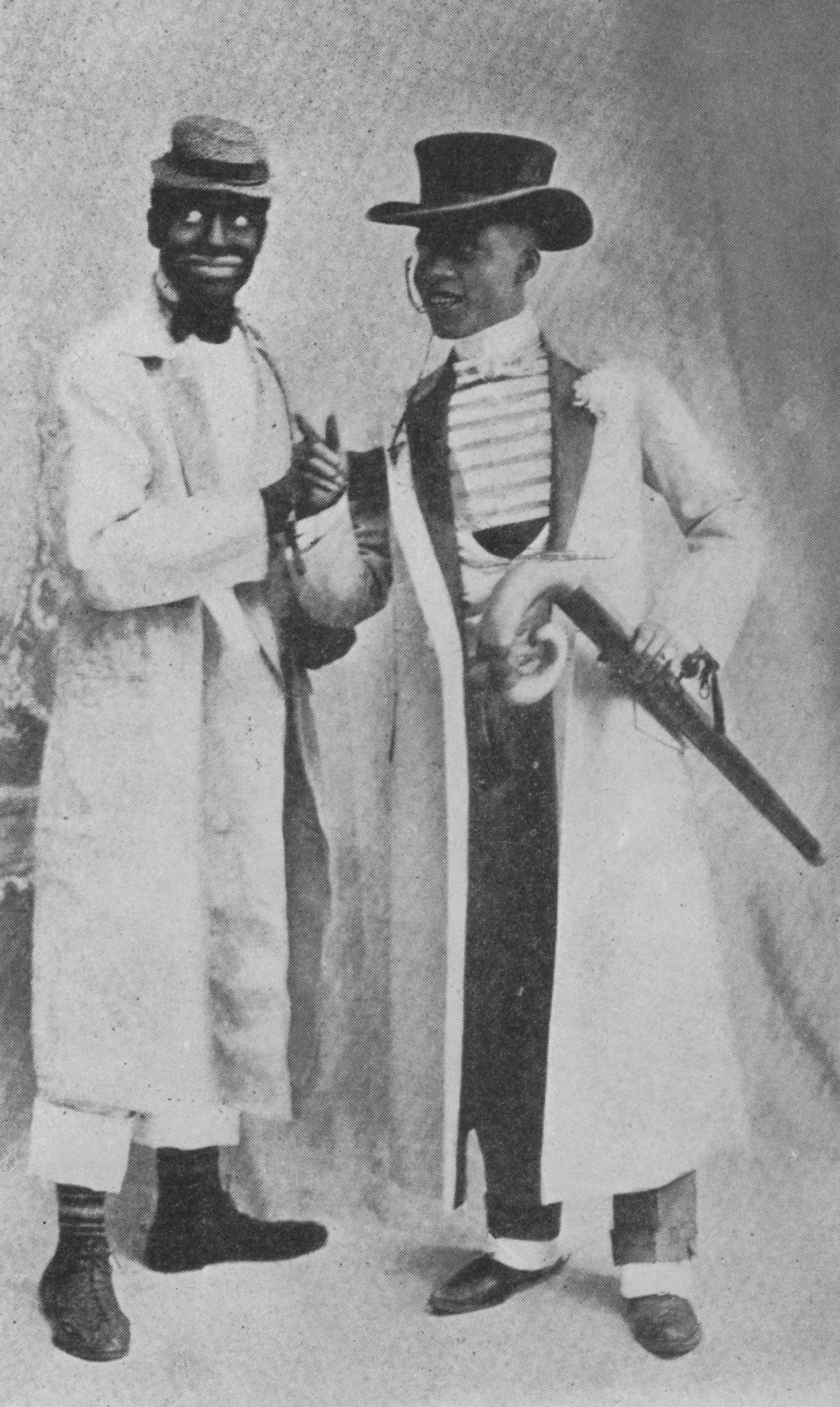

| Robert Cole and Rosamond Johnson

| 157-158

|

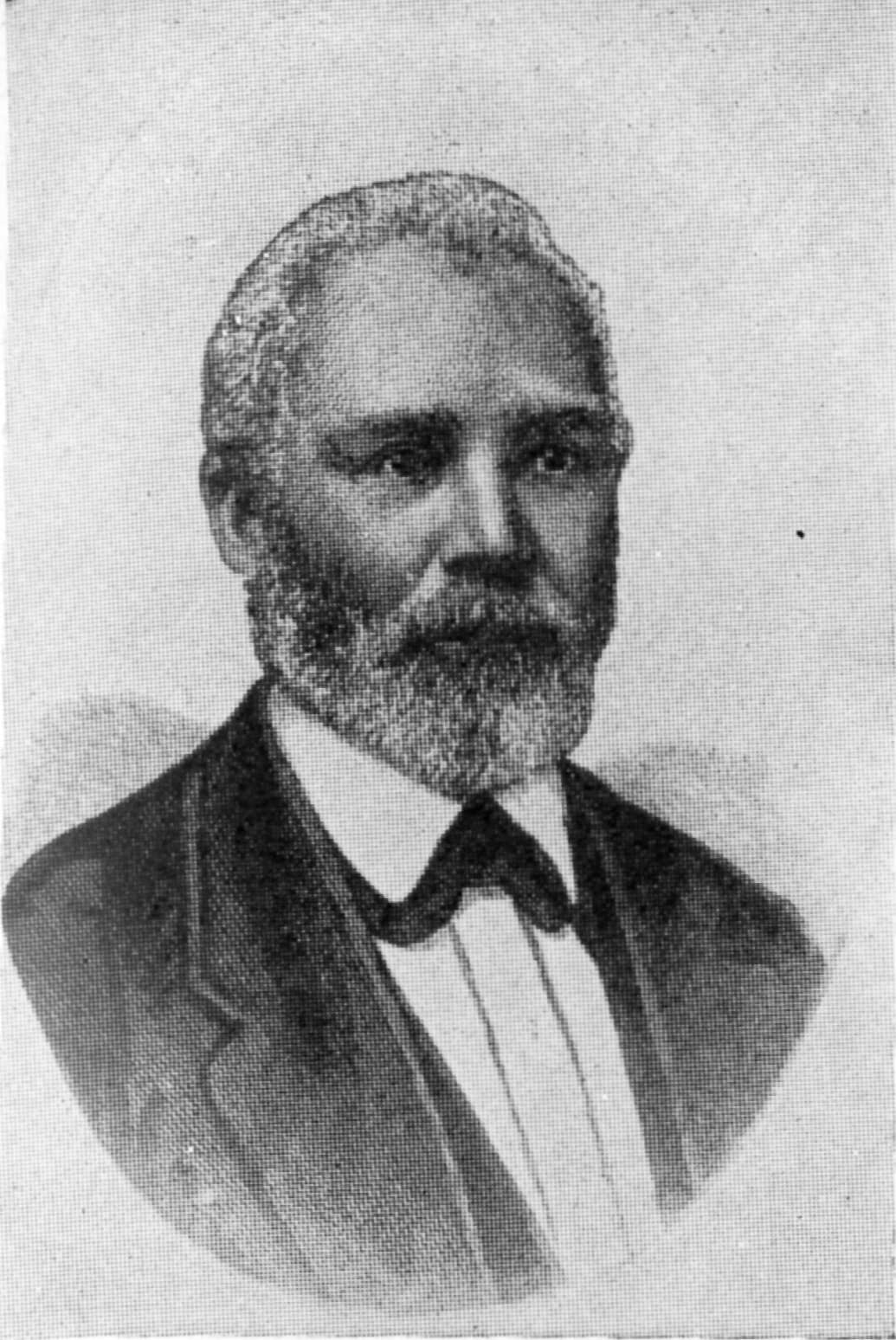

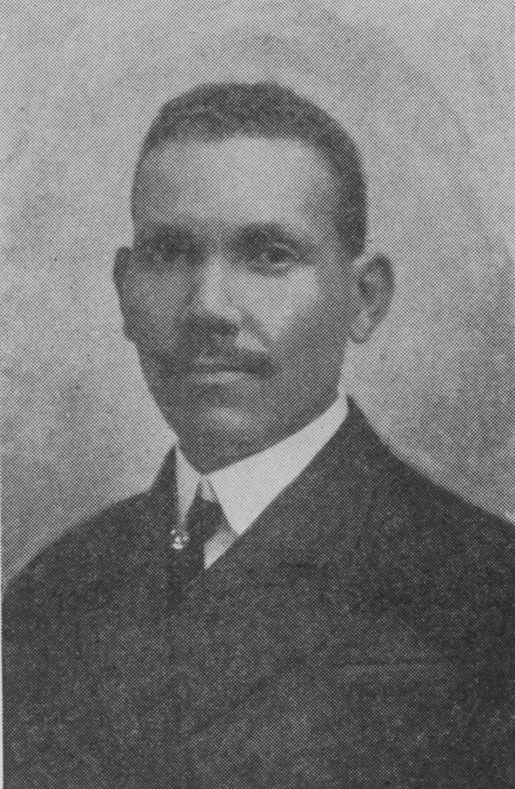

| Thomas J. Bowers

| 200-201

|

| Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield

| 202-203

|

| Justin Holland

| 206-207

|

| Madame Selika

| 222-223

|

|

Flora Batsen Bergen,

Sidney Woodward,

Abbie Mitchell, and

Gerald Tyler

| 232-233

|

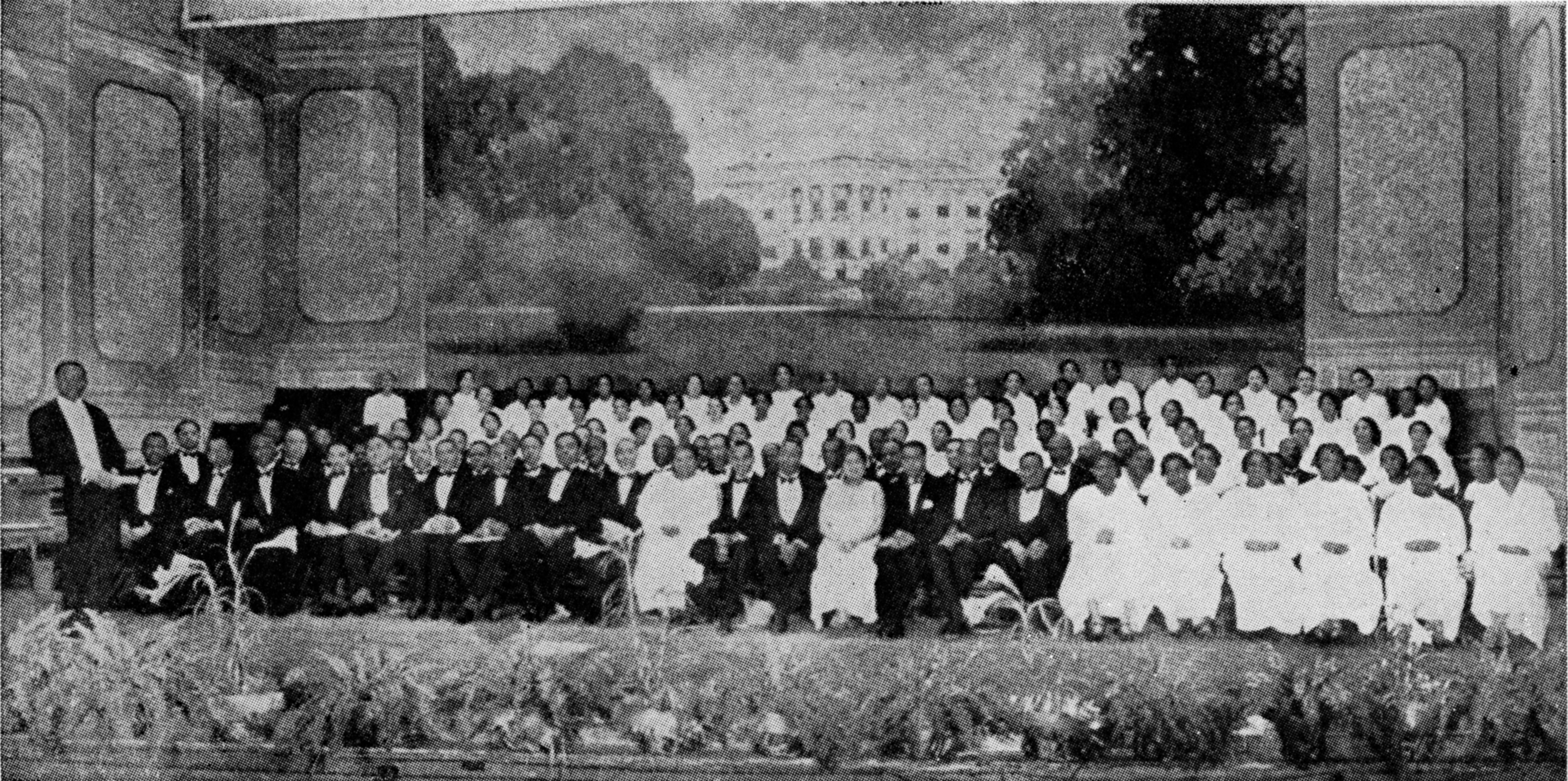

| Coleridge-Taylor Society, Washington, D. C., 1900, with the Great Composer as Director

| 244-245

|

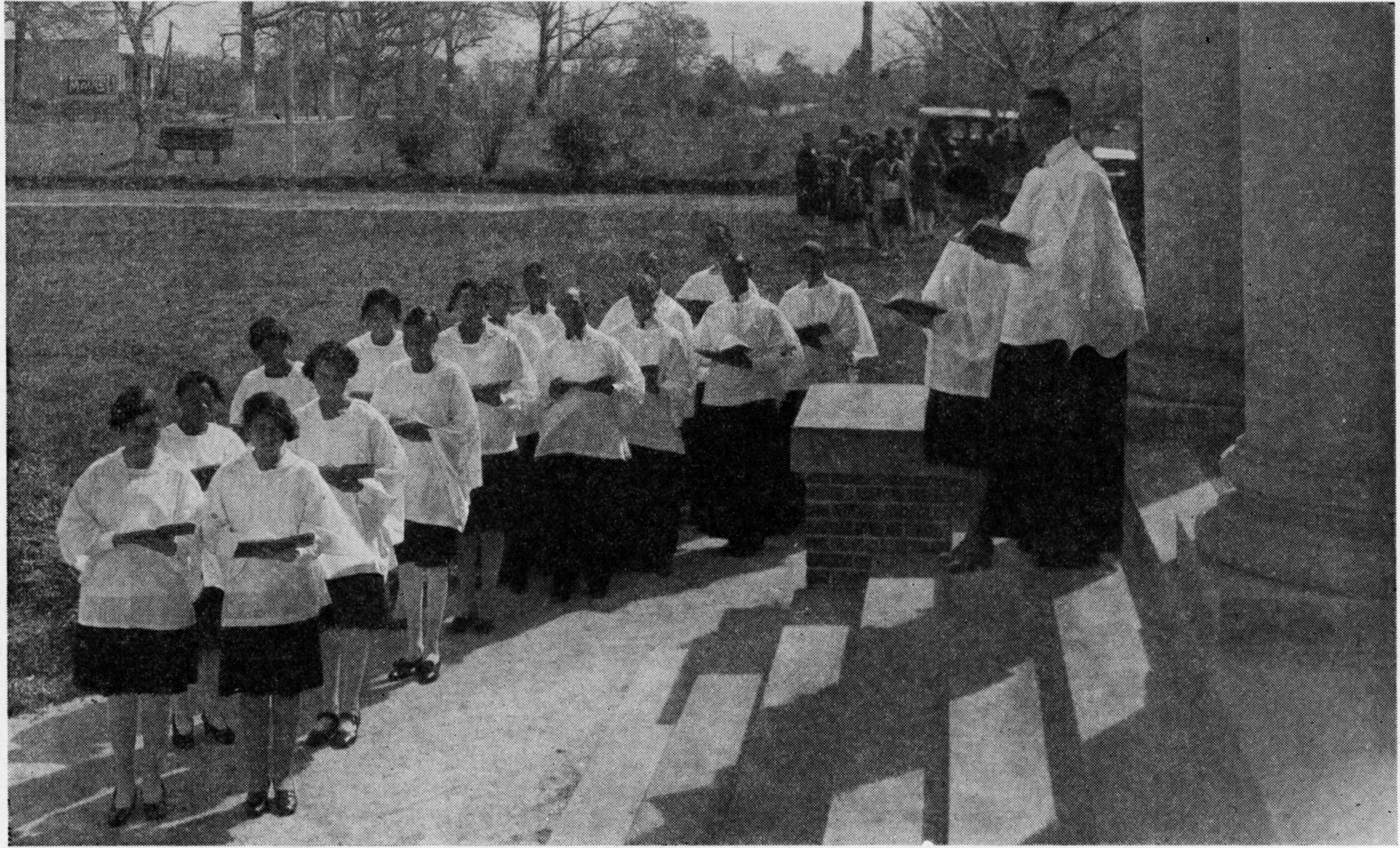

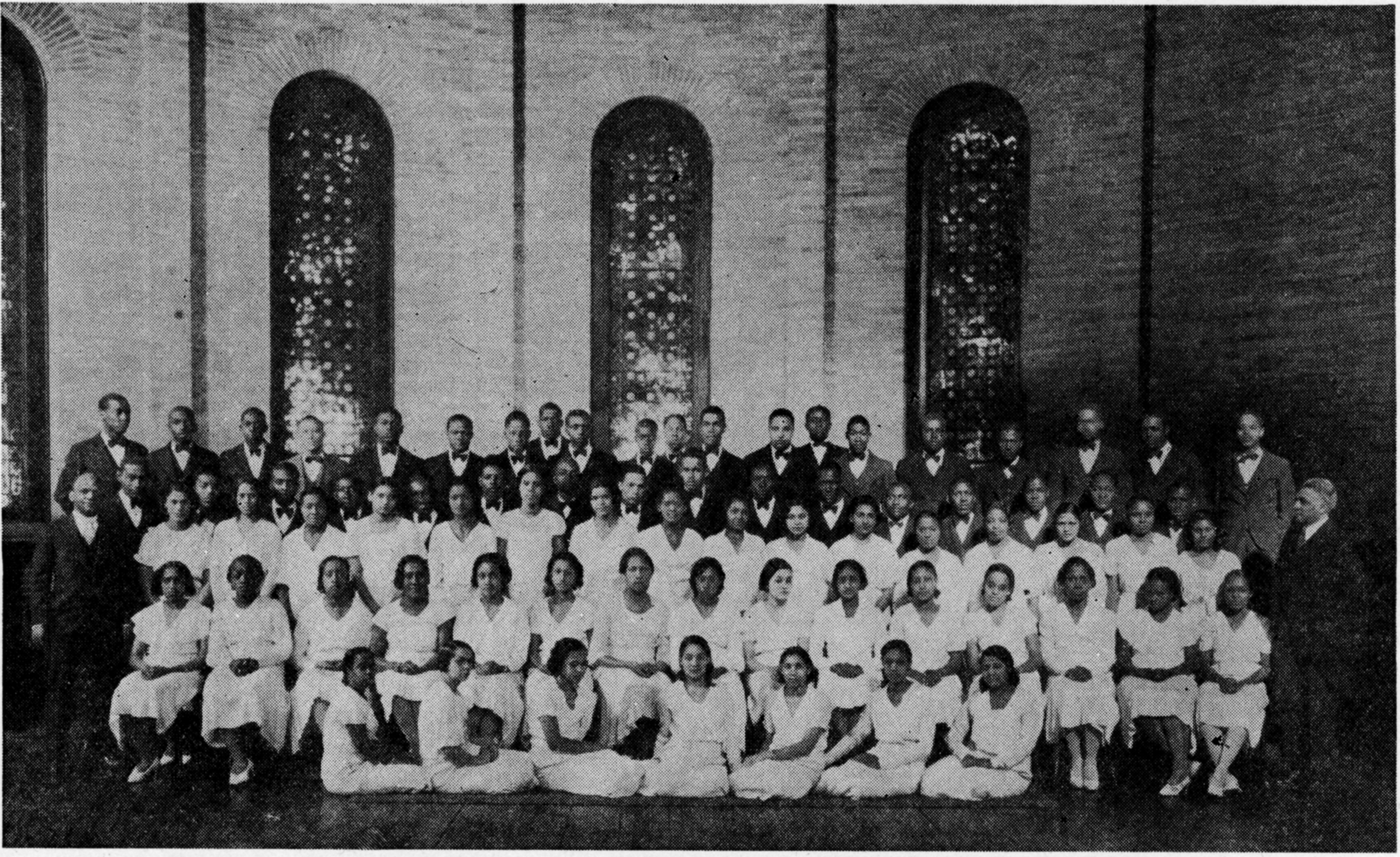

| The Hampton Choir

| 248-249

|

| Vested Choir, Palmer Memorial Institute, Sedalia, N. C.

| 252-253

|

|

Harriet Gibbs Marshall,

Kitty Skeene Mitchell,

E. Azalia Hackley, and

Pedro T. Tinsley

| 254-255

|

|

Zulu Singers in London and

An African Scene

| 258-259

|

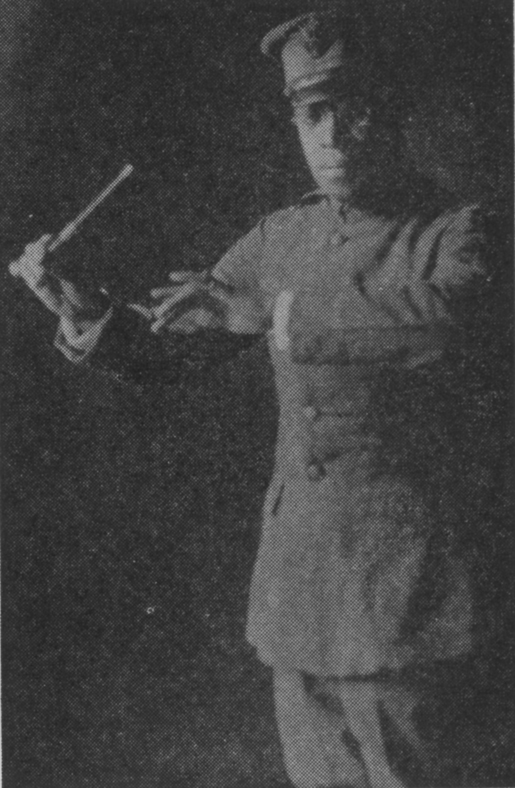

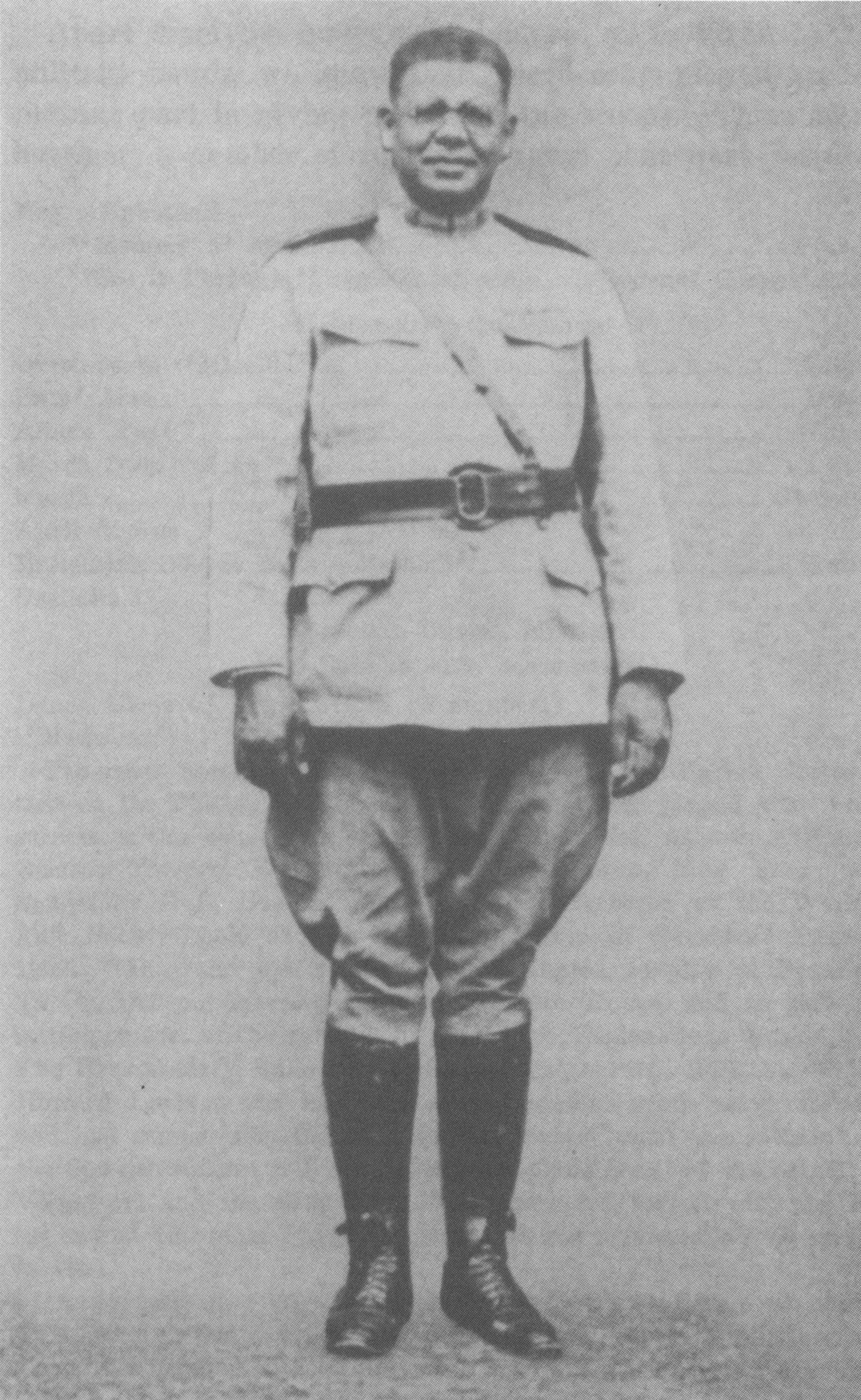

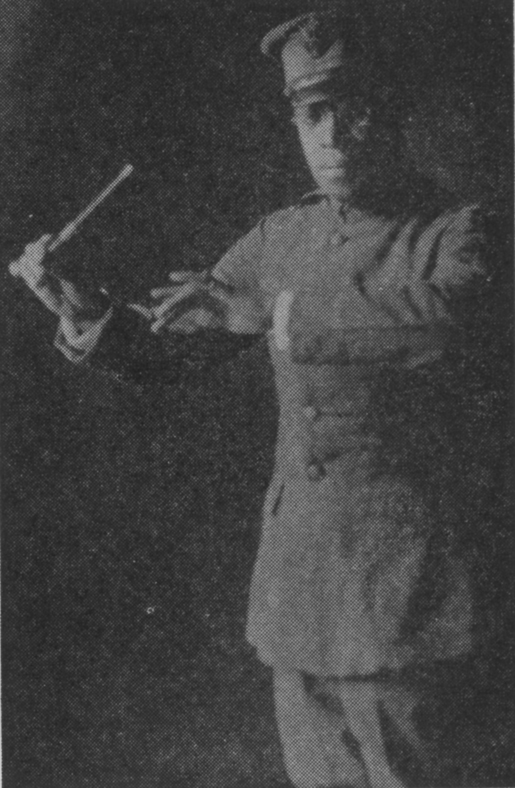

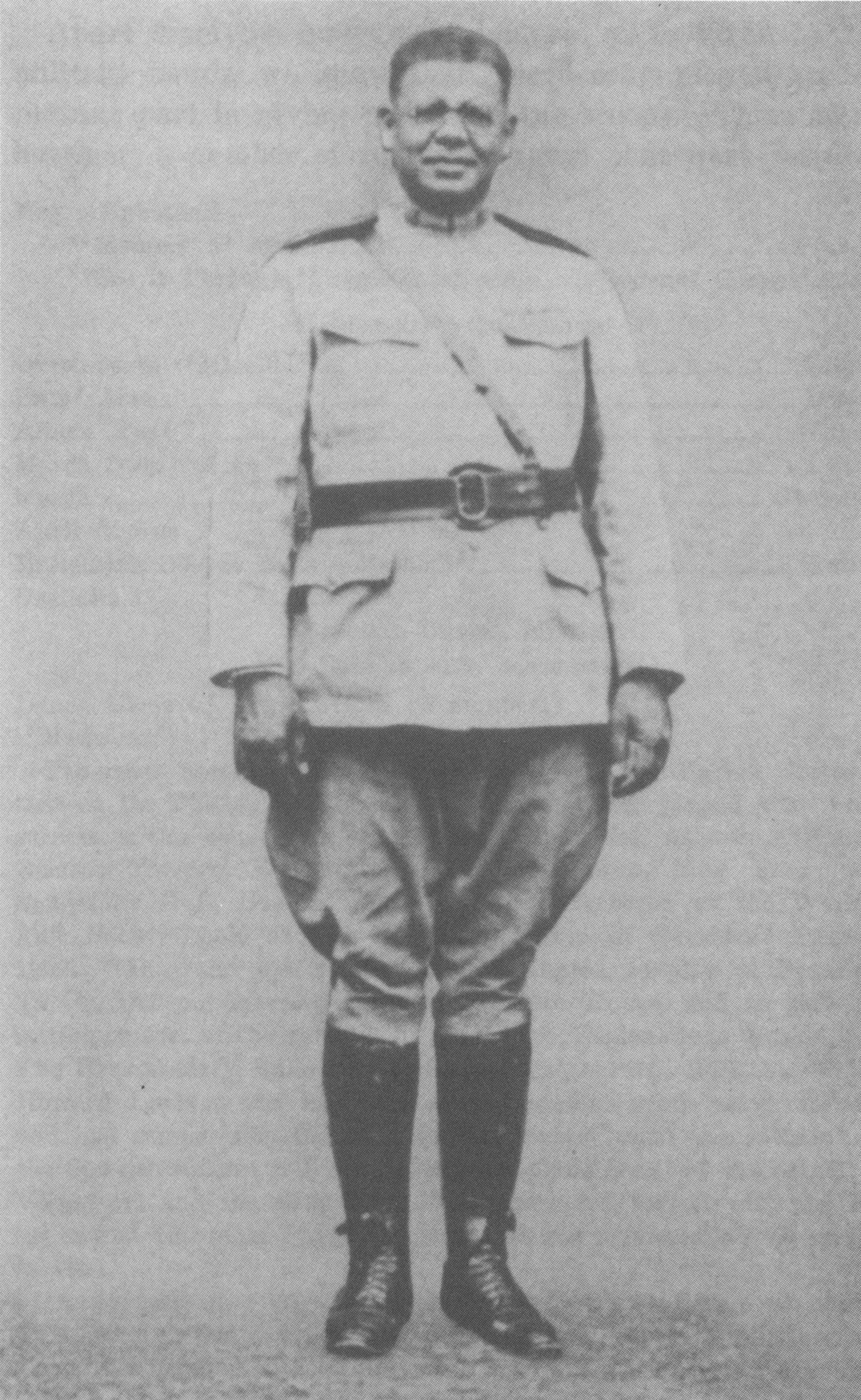

| Walter Loving, Director, Philippine Constabulary

Band,

| 272-273

|

| Naubat Khan Kalawant

| 278-279

|

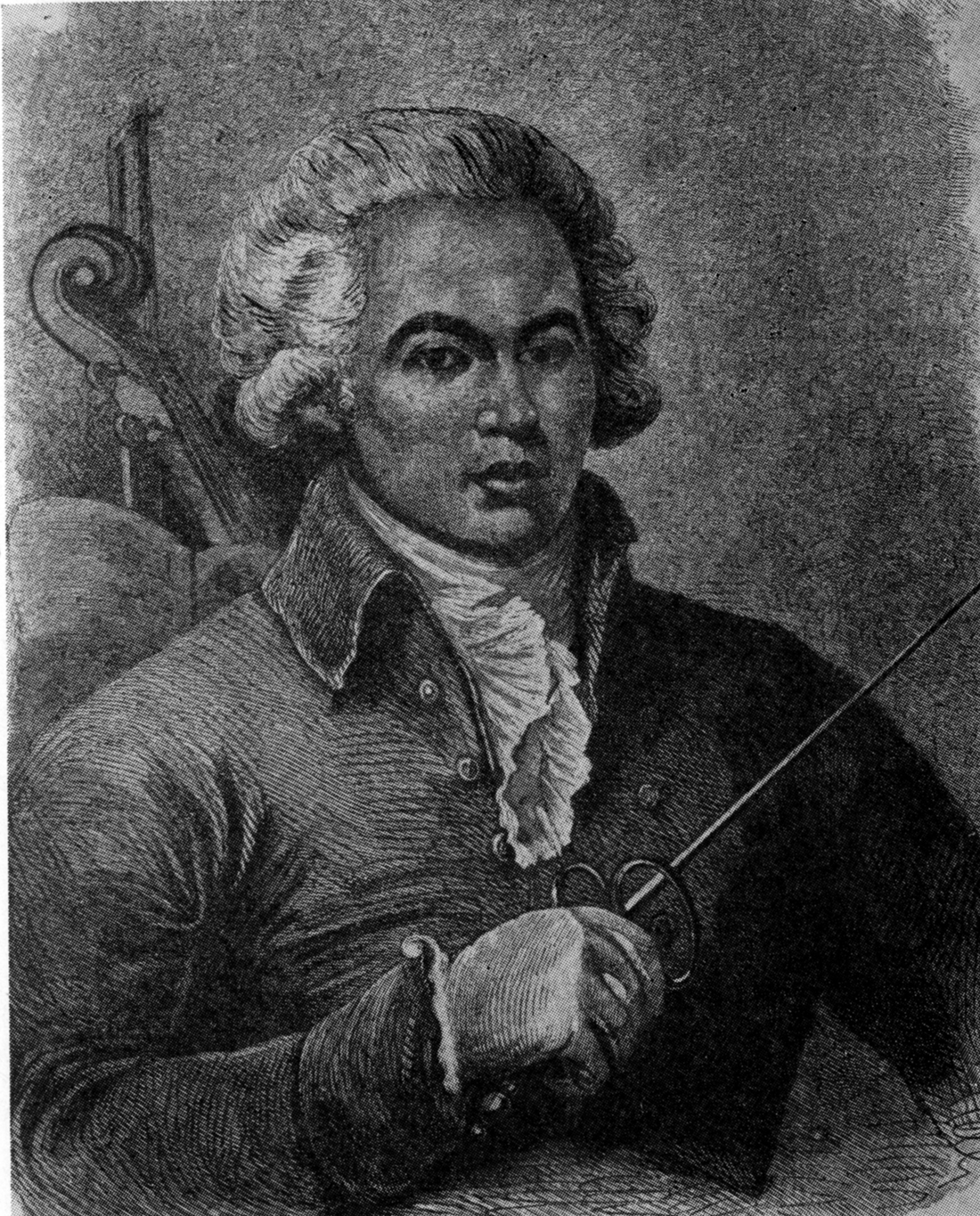

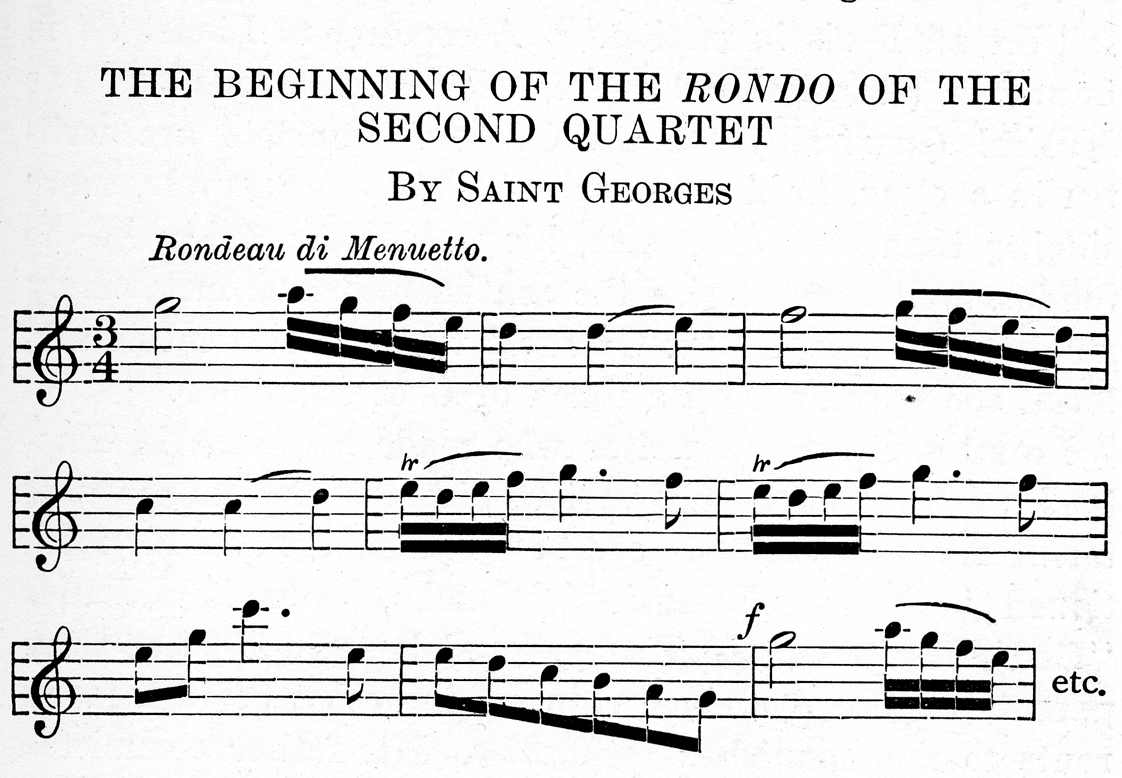

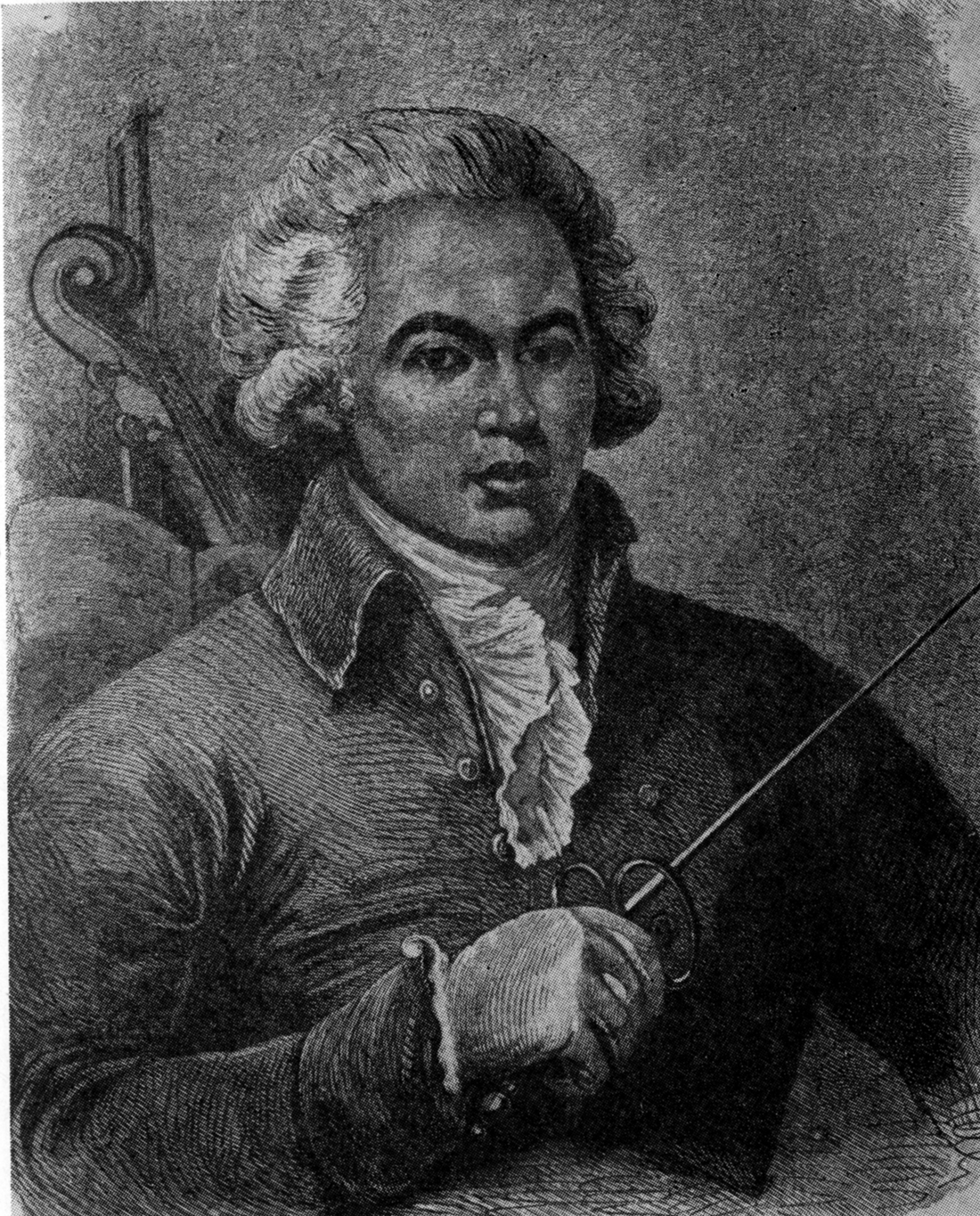

| Le Chevalier de Saint Georges

| 290-291

|

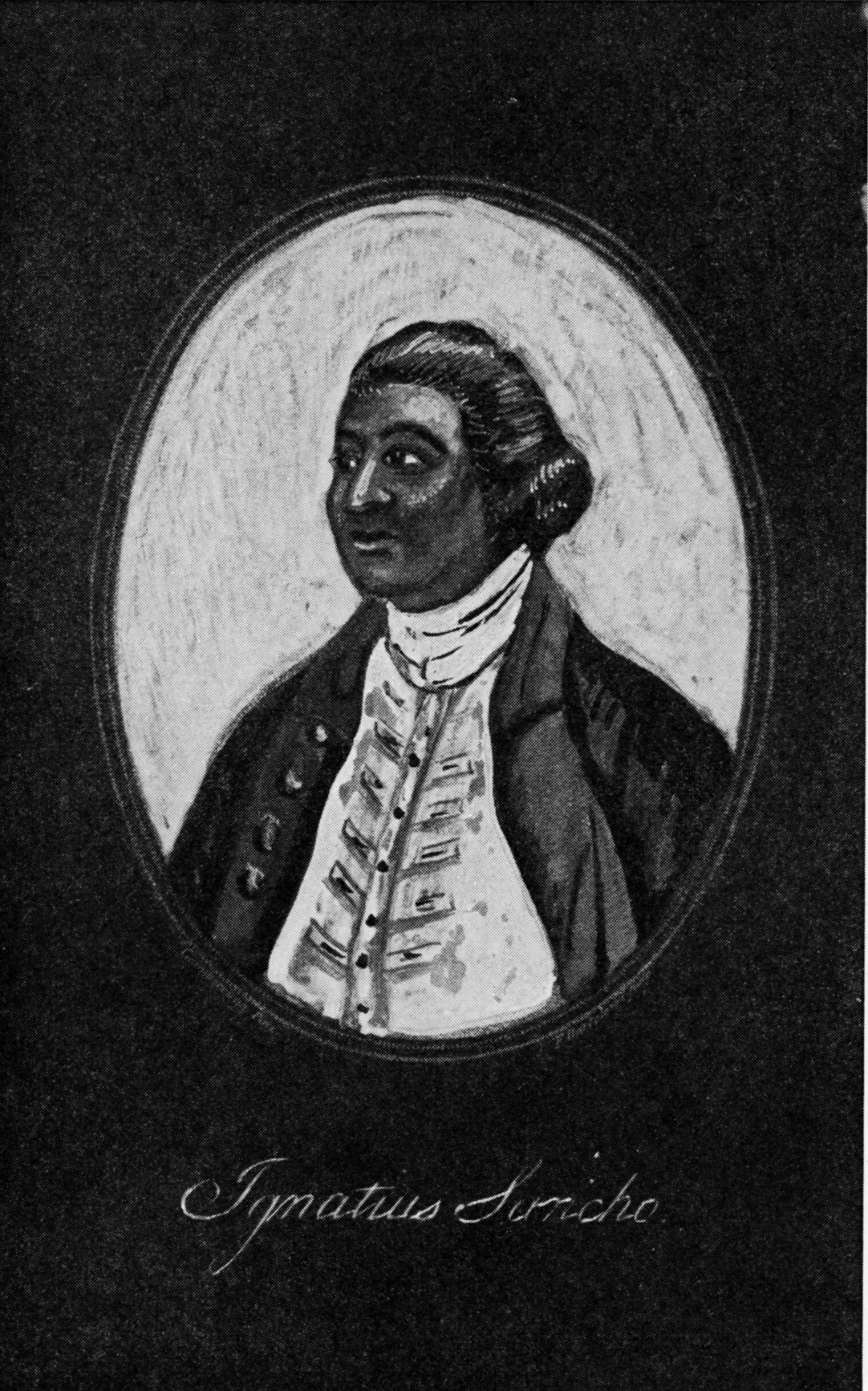

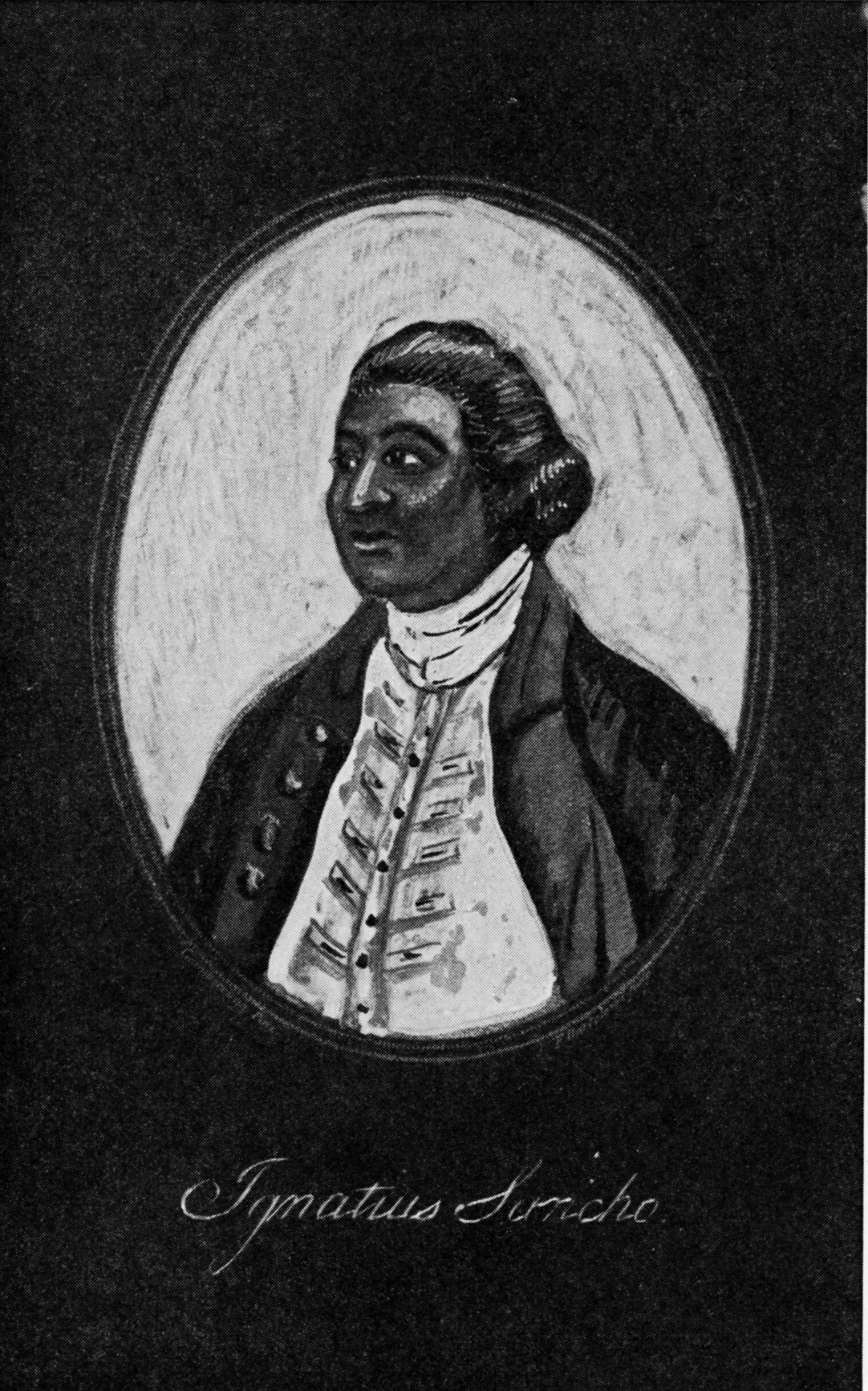

| Ignatius Sancho

| 294-295

|

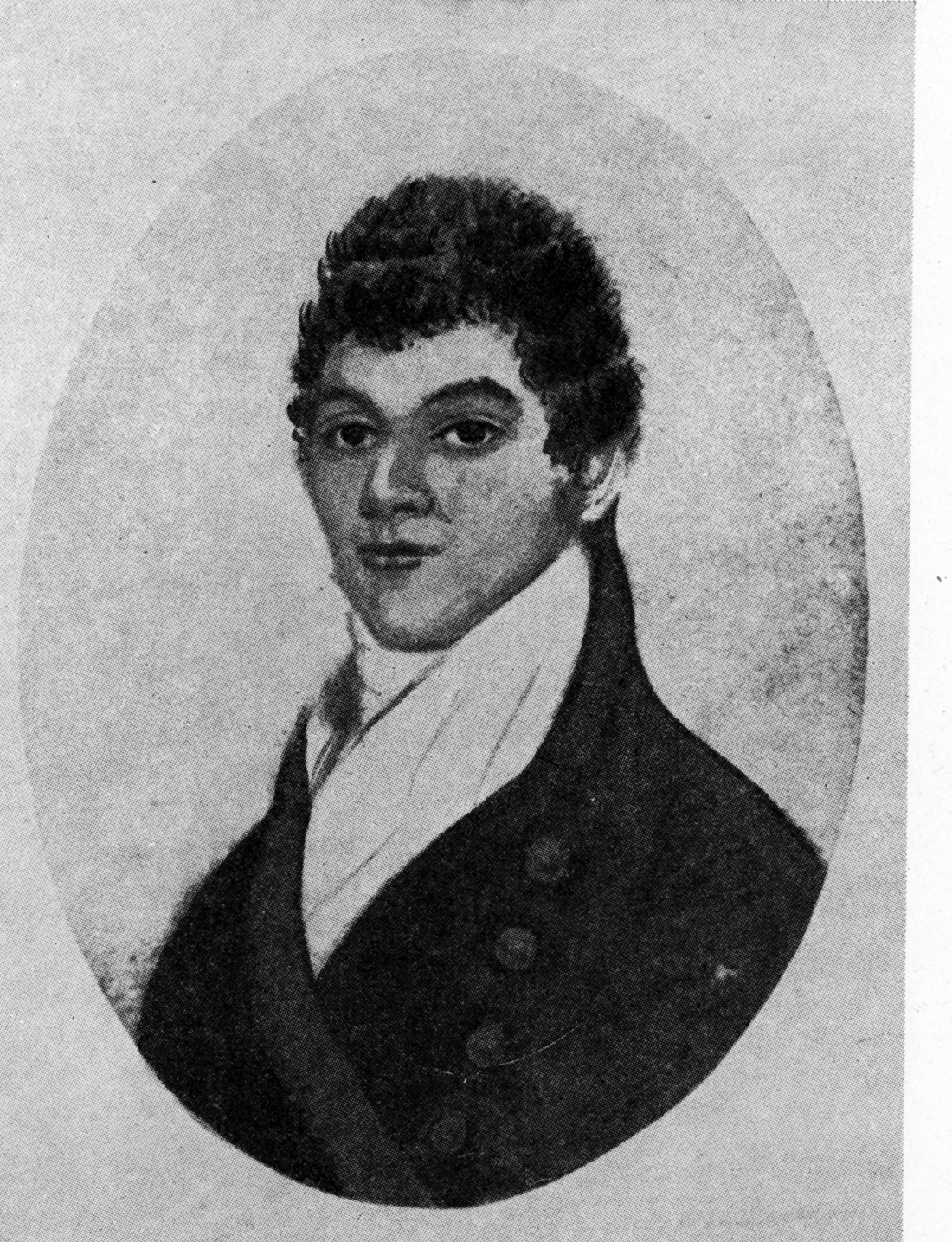

| George Polgreen Bridgetower

| 296-297

|

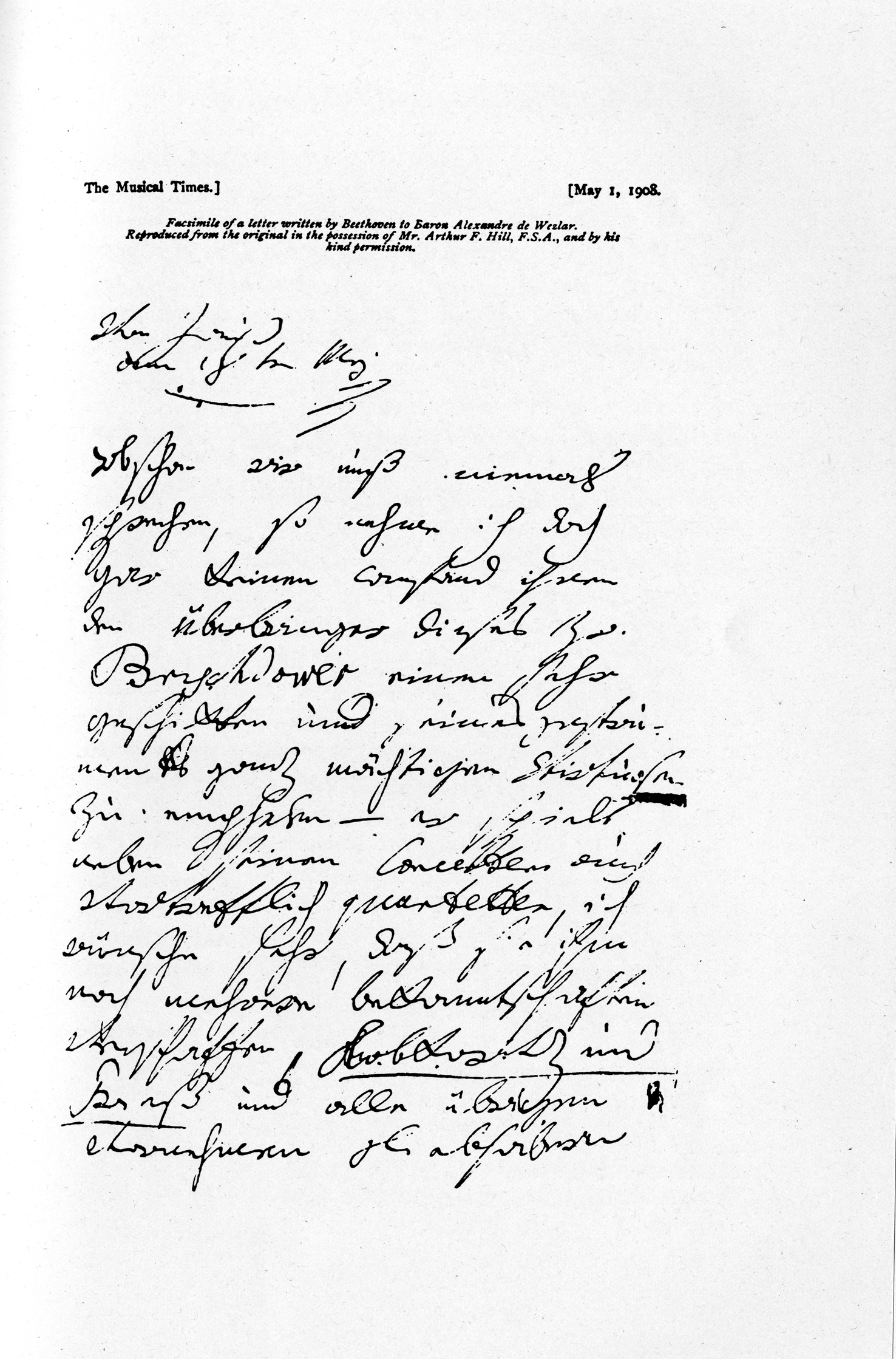

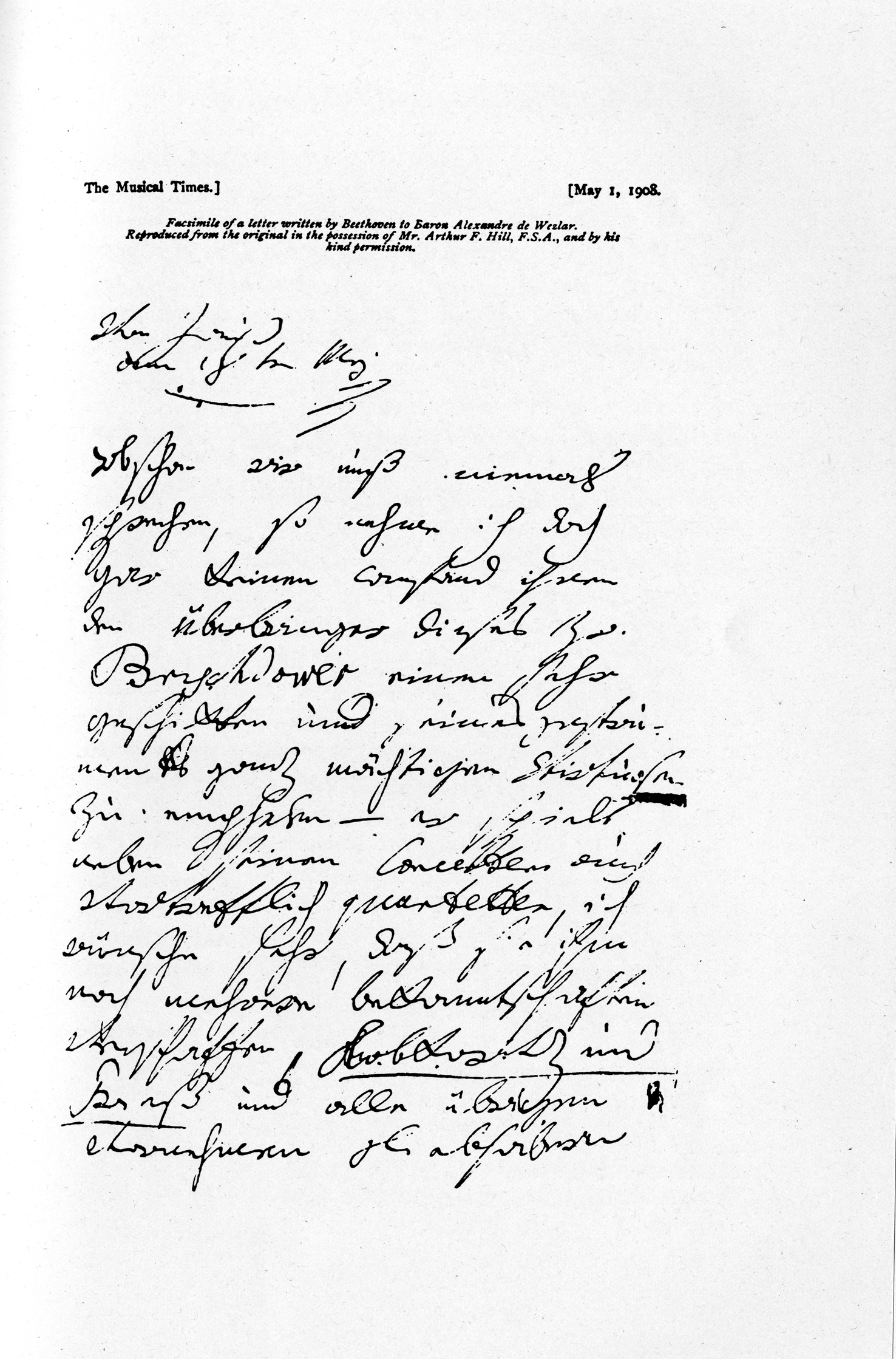

| Facsimile of a letter written by Beethoven to Baron Alexandre de Wezlar

|

298-299

|

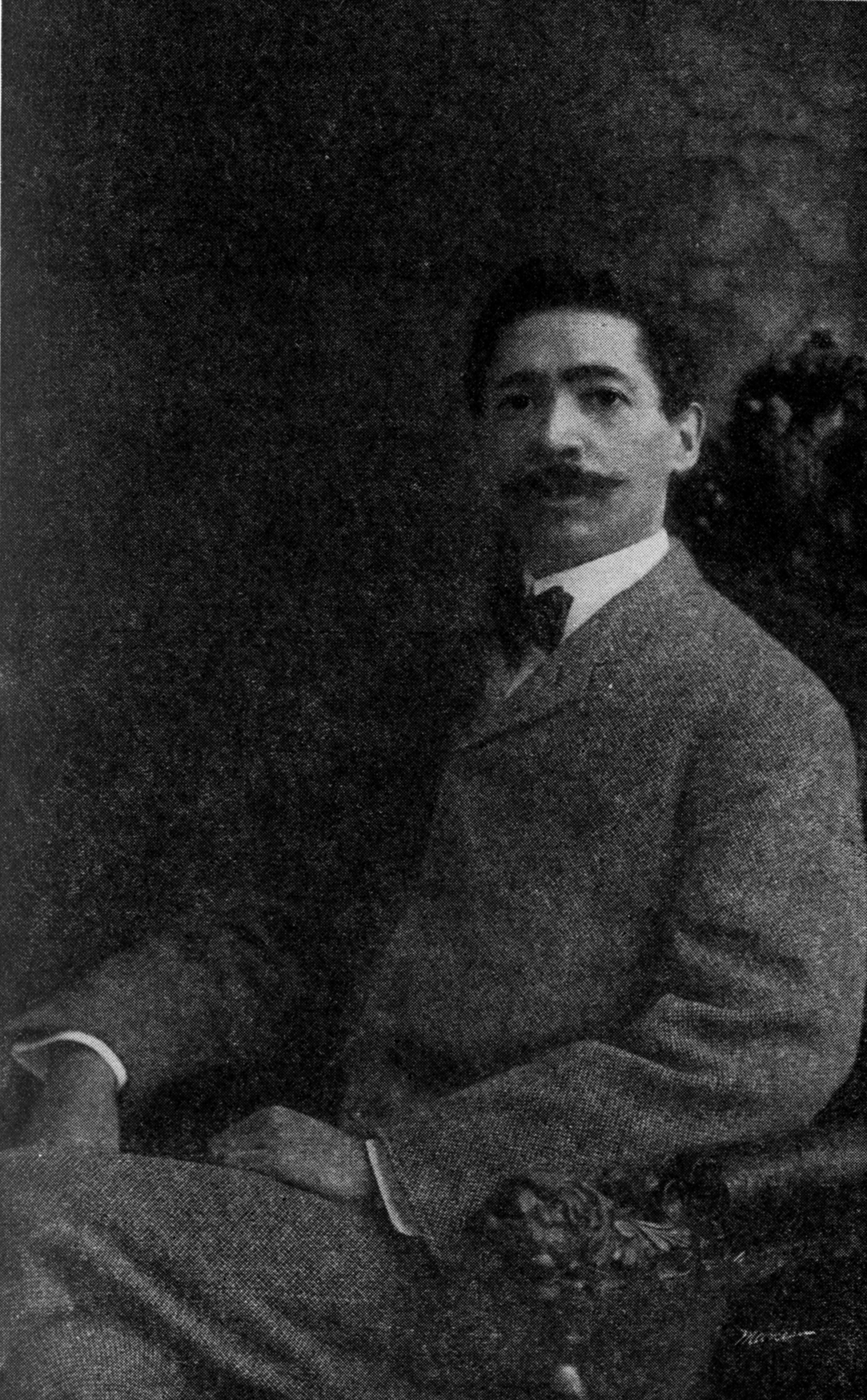

| A. Carlos Gomez

| 304-305

|

| Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

| 308-309

|

|

|

|

|

Luranah Ira Aldridge,

Frederick Olaff Ira Aldridge,

Joseph White, and

Brindis de Sala

| 314-315

|

| Montague Ring

| 316-317

|

| Harry T. Burleigh

| 324-325

|

| Clarence Cameron White

| 330-331

|

| William Grant Still

| 334-335

|

| R. Nathaniel Dett

| 336-337

|

| Dett Choral Society, Washington, D. C.

| 338-339

|

| Roland Hayes

| 352-353

|

|

Lillian Evanti,

Charlotte Wallace Murray,

Marian Anderson, and

Florence Cole-Talbert

| 356-357

|

| Jules Bledsoe

| 360-361

|

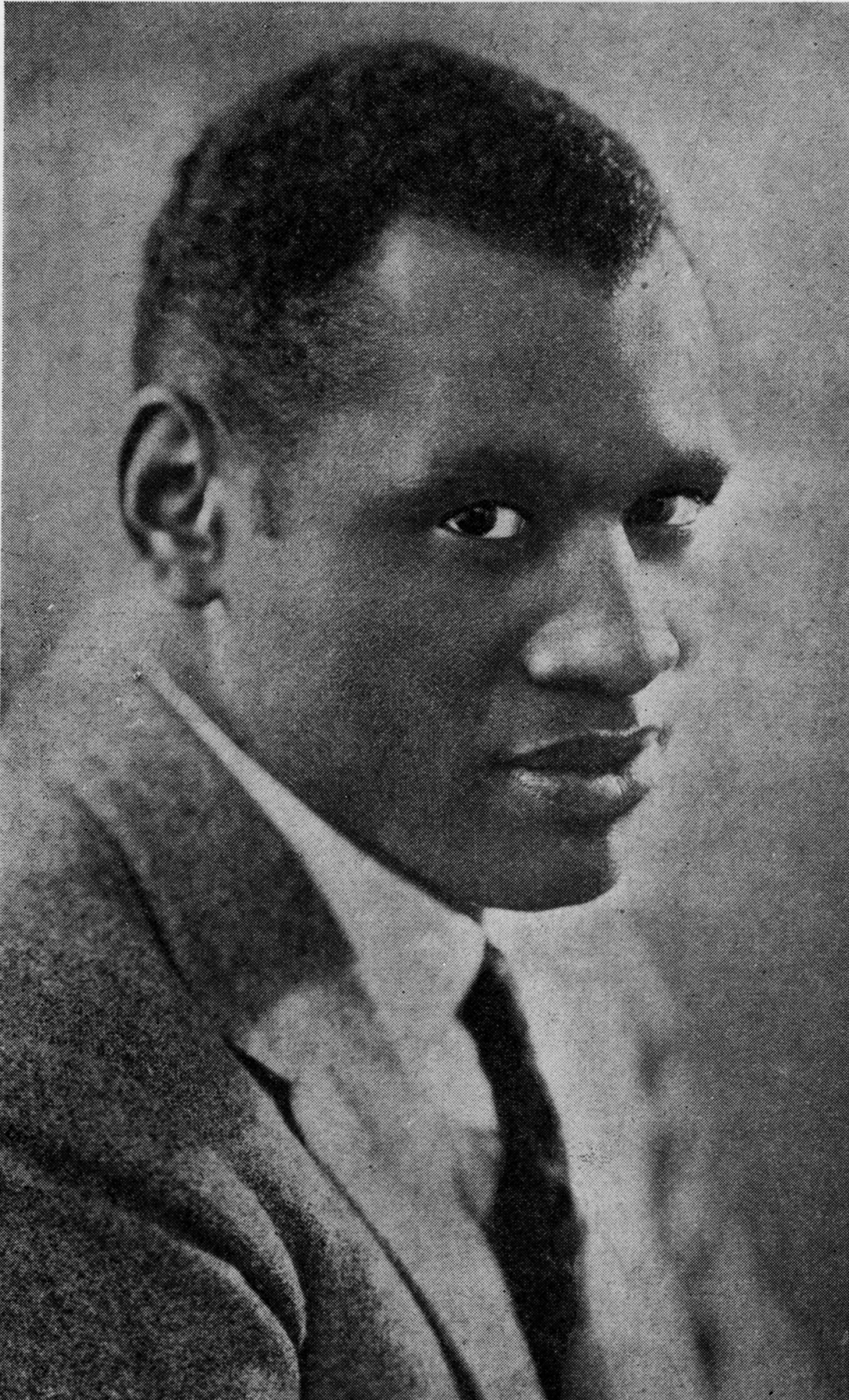

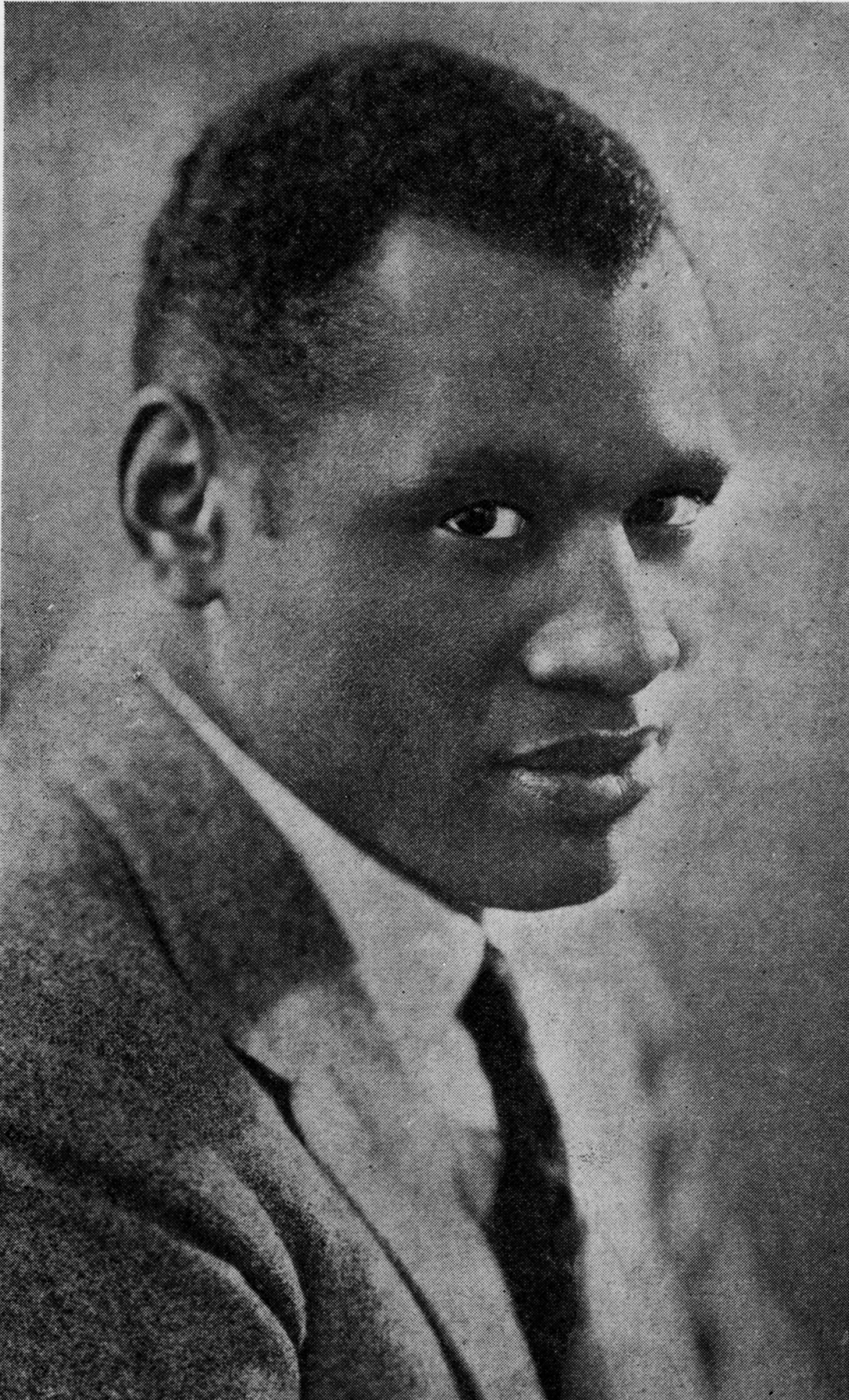

| Paul Robeson

| 372-373

|

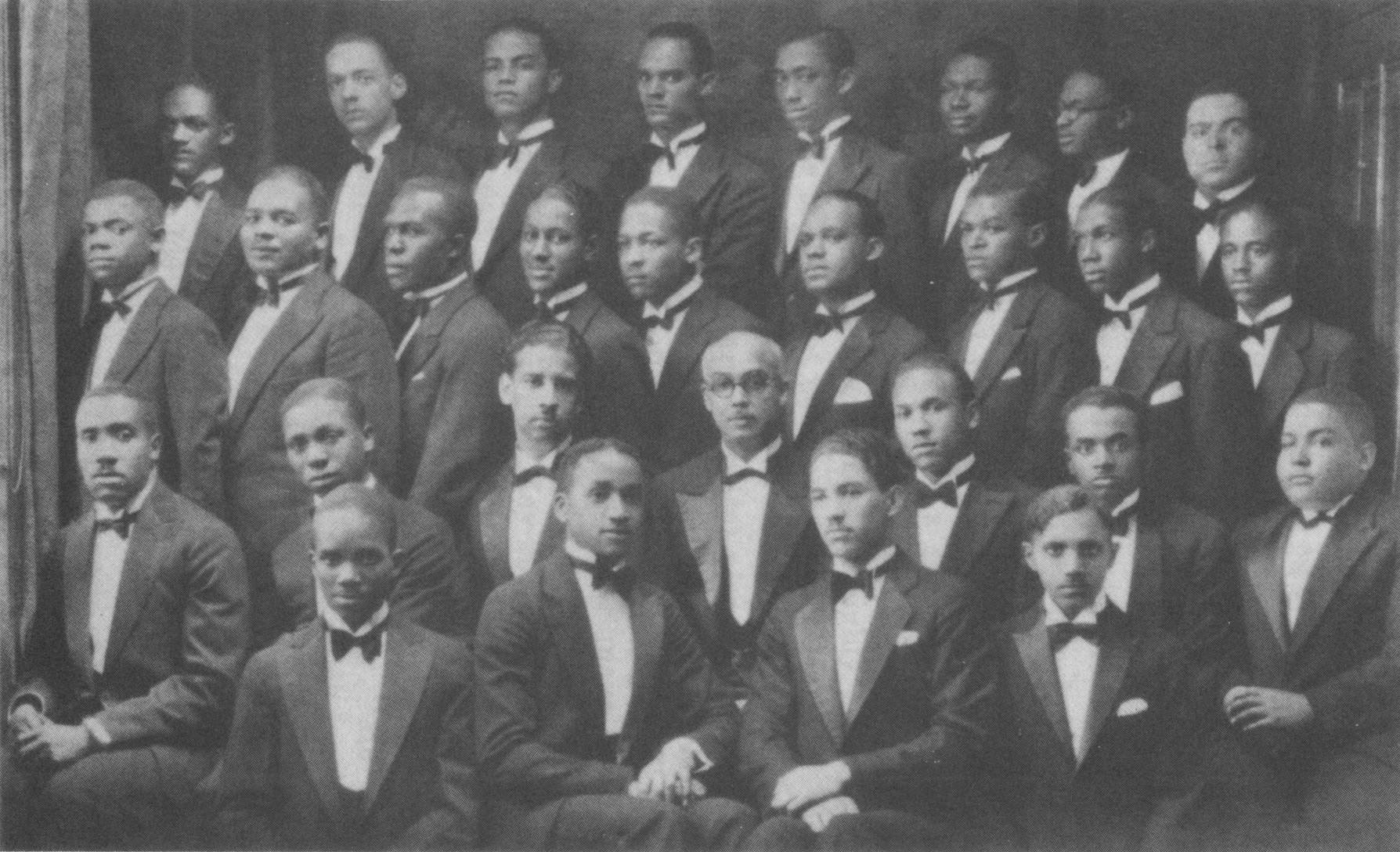

| Howard University Glee Club

| 376-377

|

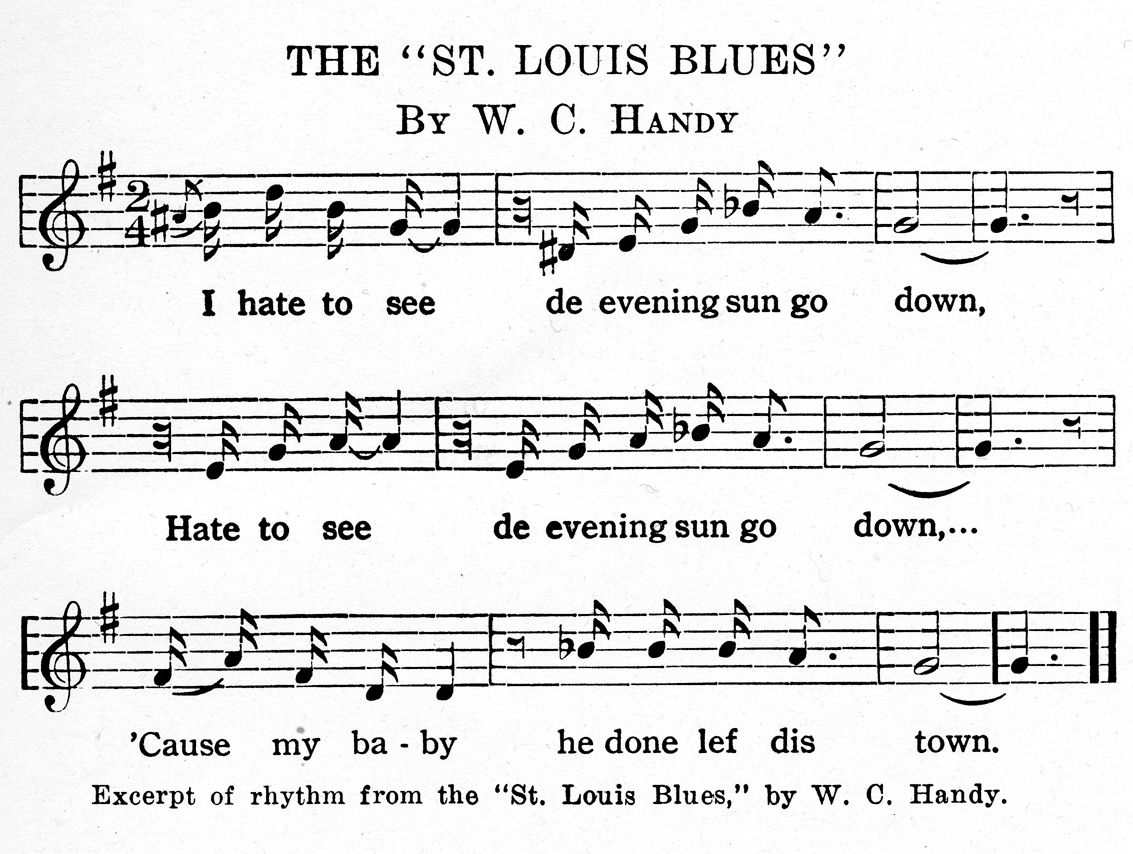

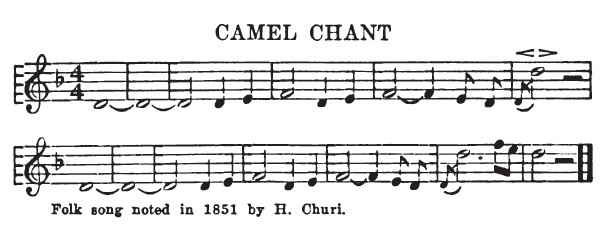

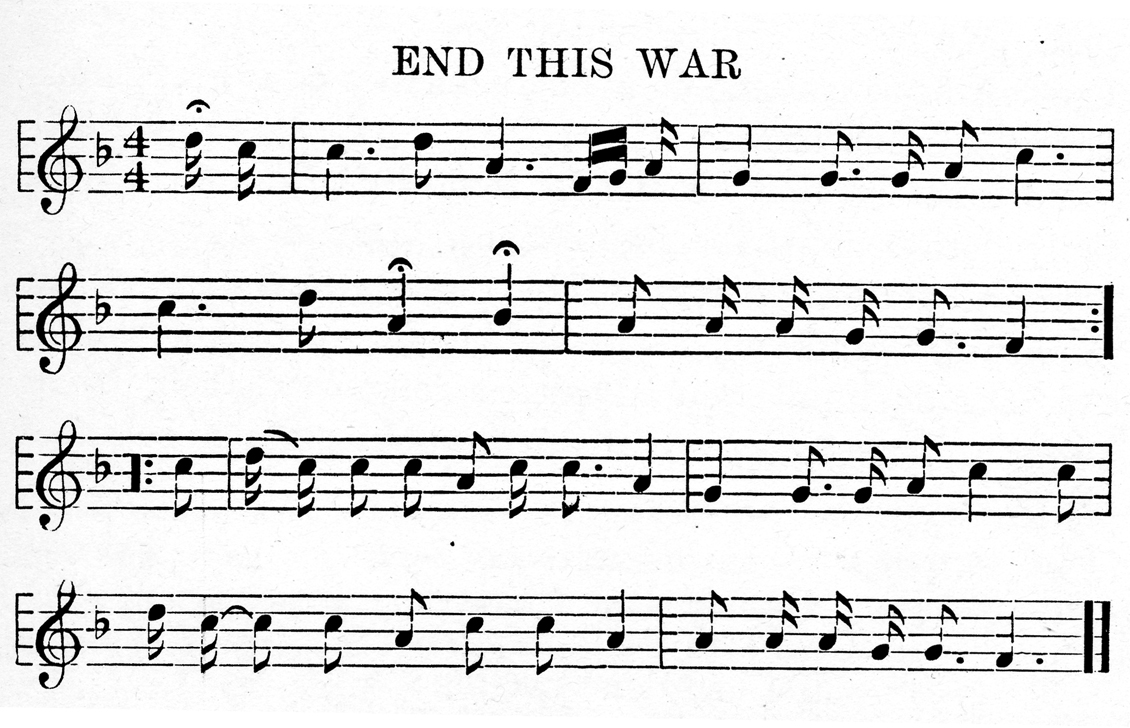

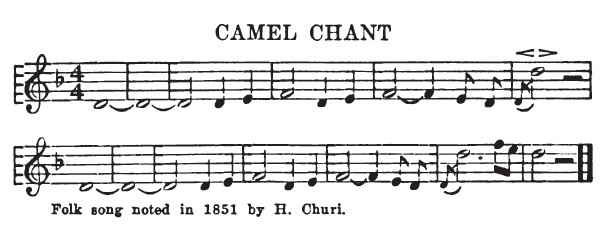

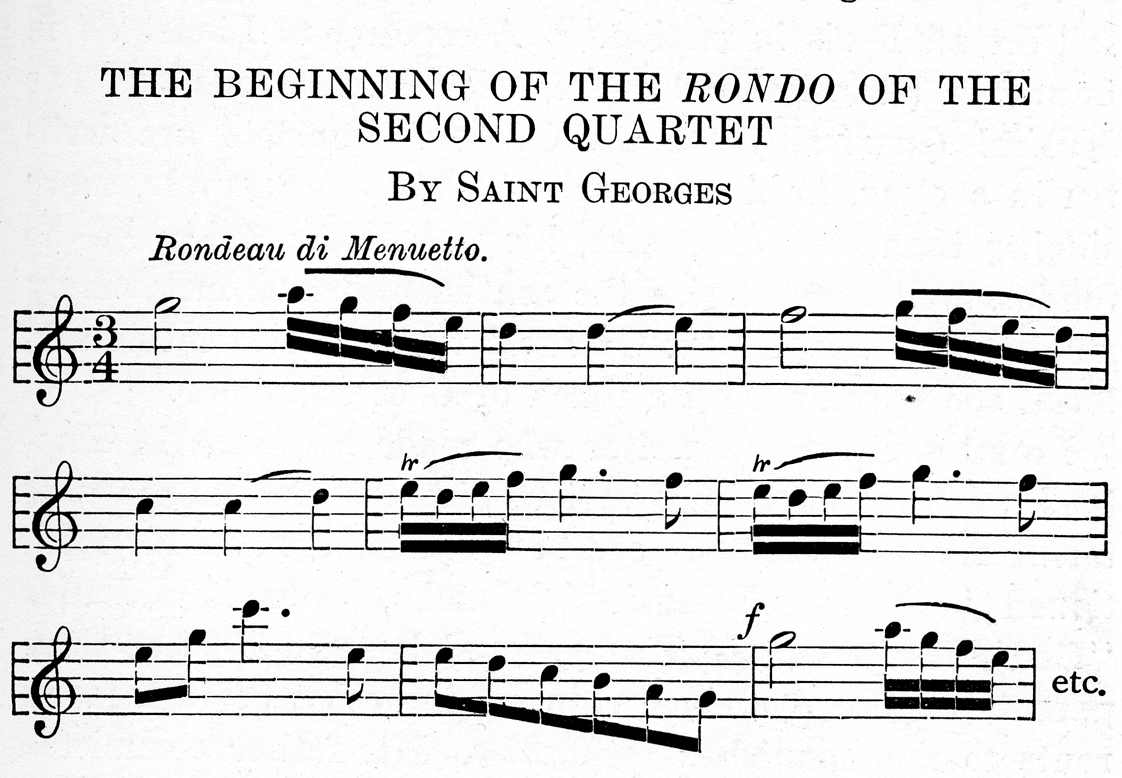

MUSICAL ILLUSTRATIONS

ILLUSTRATIONS*

| [2nd edition, 1943]

| Between Pages

|

| African Dance and an

An African Painting;

African Musical Instruments

| 18-19

|

| Marimba, or Xylophone;

African Drums

| 30-31

|

| Fisk Jubilee Singers;

Zulu Singers in London and

an African Scene

| 54-55

|

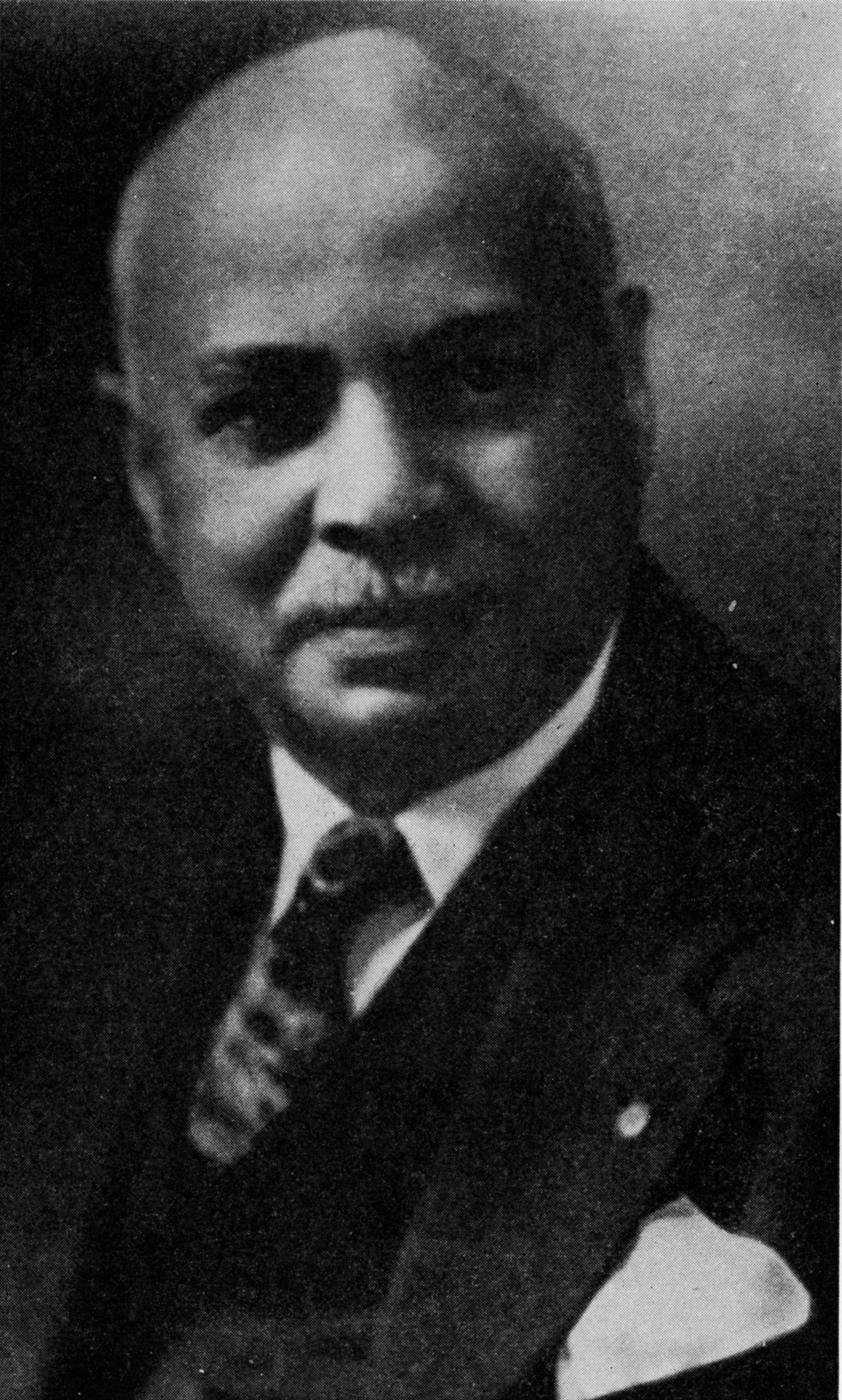

| Will Marion Cook and

William C. Handy

| 132-133

|

| Duke Ellington and His Orchestra;

Cab Calloway,

Count Basie,

Lionel Hampton, and

Tiny Bradshaw

| 136-137

|

| Louis Jordan,

Andy Kirk,

Fats Waller, and

Louis Armstrong;

Erskine Hawkins,

Noble Sissle,

Jimmie Lunceford, and

Earl Hines

| 154-155

|

| Robert Cole and Rosamond Johnson;

Williams and Walker

| 158-159

|

| Justin Holland,

Thomas J. Bowers,

Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, and

Madame Selika;

Flora Batsen Bergen,

Sidney Woodward,

Abbie Mitchell, and

Gerald Tyler

| 222-223

|

| Coleridge-Taylor Society, Washington, D. C., 1900, with the Great Composer as Director;

The Hampton Choir

| 244-245

|

| Harriet Gibbs Marshall,

Kitty Skeene Mitchell,

E. Azalia Hackley, and

Pedro Tinsley;

Todd Duncan,

Caterina Jarboro,

Anne Wiggins Brown, and

Dorothy Maynor

| 254-255

|

| Walter Loving, Director of the Philippine Constabulary

Band;

Melville Charlton,

James Reese Europe,

W. L. Dawson, and

Basile Barres

| 272-273

|

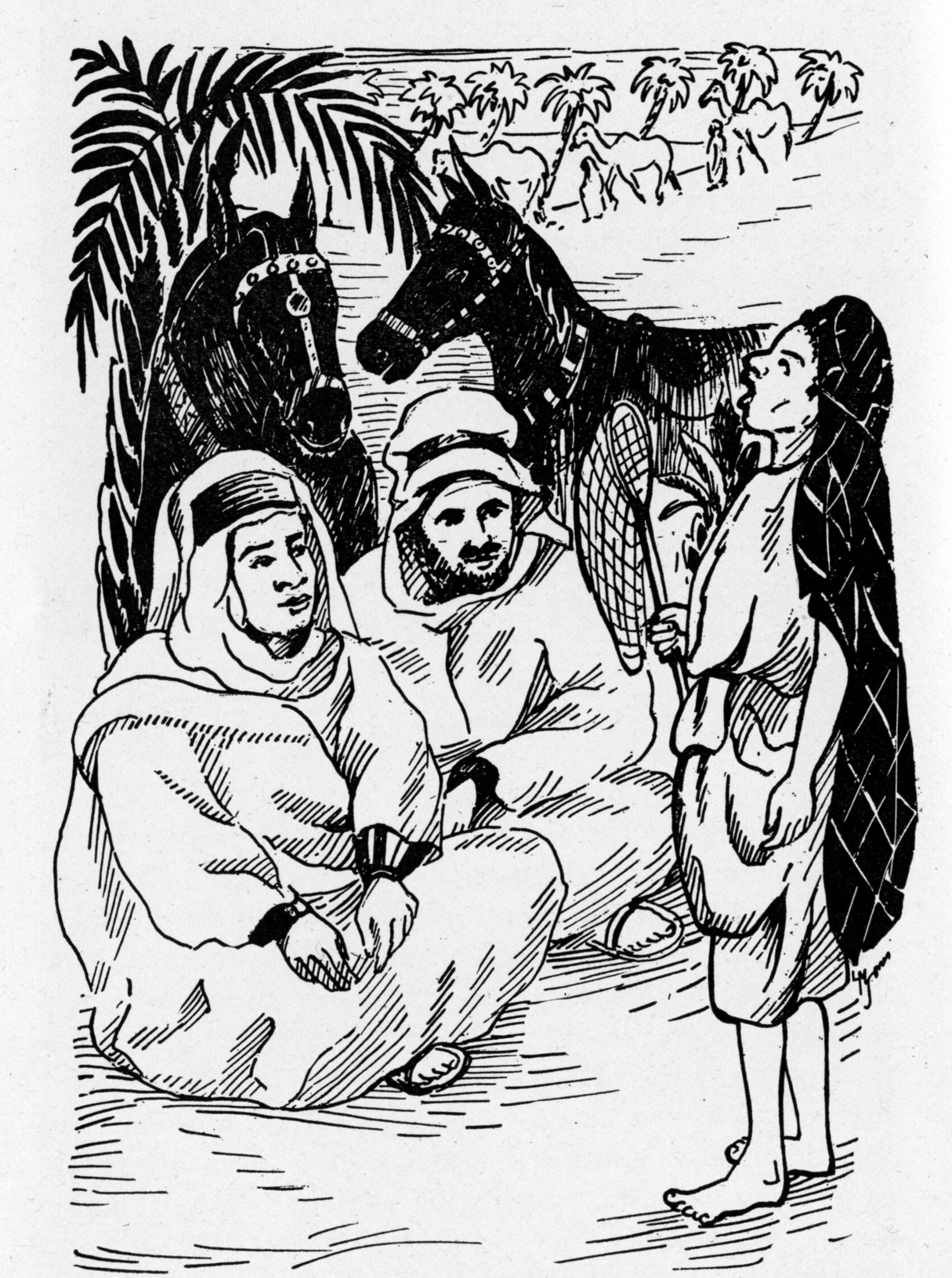

| Naubat Khan Kalawant and

Mabeb Discovered

| 278-279

|

| Le Chevalier de Saint Georges and

Ignatius Sancho

| 290-291

|

| Facsimile of a letter from Beethoven to Baron Alexandre de Wezlar

|

298-299

|

| George Polgreen Bridgetower and

A. Carlos Gomez

| 302-303

|

| Luranah Ira Aldridge,

Montague Ring ,

Joseph White, and

Brindis de Sala;

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

| 306-307

|

| Harry T. Burleigh and

Clarence Cameron White

| 328-329

|

| William Grant Still and

R. Nathaniel Dett

| 336-337

|

| Dett Choral Society and

Vested Choir, Palmer Memorial Institute

| 338-339

|

| Roland Hayes and

Marian Anderson

| 356-357

|

| Jules Bledsoe and

Paul Robeson

| 372-373

|

| Charlotte Wallace Murray,

Lillian Evanti,

Etta Moten, and

Florence Cole-Talbert;

Howard University Glee Club

| 378-379

|

INTRODUCTION

It is with a distinct sense of pleasure and privileged duty

that I give the readers of this excellent book a short sketch

of the career of Maud Cuney-Hare. One who does not already know of the versatility of this remarkably talented

woman will doubtless be amazed at the diversified character

of her activities.

Mrs. Hare is a pianist, lecturer and writer whose devotion to the highest ideals of her art has compelled admiration. She is the daughter of the late Norris Wright Cuney

of Galveston, Texas, and Adelina Dowdy Cuney of Woodville, Mississippi. She was born in Galveston, Texas, February 16, 1874, and was graduated from the Central High

School of that city. Her musical education was received at

the New England Conservatory in Boston and later under

private instructors among whom were Emil Ludwig, a

pupil of Rubenstein, and Edwin Klahre, a pupil of Liszt.

Following the completion of her work under these masters,

she became director of music at the Deaf, Dumb and Blind

Institute, of Texas, and at Prairie View State College in

the same State. In 1906 she returned to Boston where she

married William P. Hare of an old and well-known Boston

family, and has since made her home there. She died there

February 13, 1936.

As a concert and lecturer-pianist Mrs. Hare has travelled

widely and as a folklorist she has collected songs from far

off beaten paths in Mexico, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico,

and Cuba. She was the first to collect and bring to the

attention of the American concert public the beauties of

New Orleans Creole Music as attested by her Creole Songs,

published by Carl Fischer and Company of New York City.

As music historian Mrs. Hare takes high rank. She collected data in this field for more than a generation. She has

exhibited her personal collection of Aframerican and Creole

music and Early American music which dates chronologically from 120 years ago. As a writer on music subjects she

has long been a valued contributor to the Musical Quarterly,

the Musical Observer, the Christian Science Monitor,

Musical America, and many other newspapers and magazines of the first order. For a number of years she edited

the column of music notes for the Crisis. As a writer of

distinction outside of the field of music she has attracted

wide attention with published works of real literary value.

In this list may be included a biography of her father and

an anthology of poems called The Message of the Trees.

During recent years Mrs. Hare found time to establish in

Boston the Musical Art Studio. Together with the musical

activities of an art centre, she fostered and promoted a

"Little Theatre" movement among the Negroes of Boston.

Included in the plays produced her original play "Antar,"

written around the life of the Arabian poet, was staged

in Boston under her personal direction. Concurrently with

these activities Mrs. Hare has appeared with great success

as recitalist, with William Howard Richardson, the baritone, at such educational centers as Wellesley College, Syracuse University, Albany (New York) Historical and Art

Association, and elsewhere in costume recitals of music of

the Orient and the Tropics.

To do any one of these things well would be a distinct

achievement, but to do all of these acceptedly as Mrs. Hare

has done is truly amazing. As a crowning achievement she

has now given us an authoritative record of Negro Musicians and Their Music — a book that is more than an anthology,

in fact a source book of great value to musicians, music

lovers and all others who wish to be well informed on matters of artistic racial development and progress.

CLARENCE

CAMERON

WHITE.

Boston, January, 1936.

CHAPTER I

AFRICA

EARLIEST

TRACES OF

AFRICAN

MUSIC —

DANCES OF

WORSHIP —

MYSTIC

DANCES —

RITES OF THE

PRIESTHOOD —

WAR

DANCES —

CEREMONIAL

DANCES —

FESTIVE

CUSTOMS —

TRIBAL

DANCES —

DANCE

FORMS OF

AFRICAN-NEGRO

INFLUENCES.

Negro music traced to its source, carries us to the continent of Africa and into the early history of that far off

land. We may even journey to one of the chief sections

said to hold the music of the past — that of Egypt, for it

was the ceremonial music of that land as well as that of

Palestine and Greece, which was the foundation of at least

one phase of modern musical art. While a continuous

recorded history that would so greatly aid in giving

knowledge of African art as well as its peculiar type of

civilization is not yet complete, we do know that, in spite

of the obscurity of the prehistoric period, there existed a

great people, as their architectural monuments alone have

proved to us.1

|

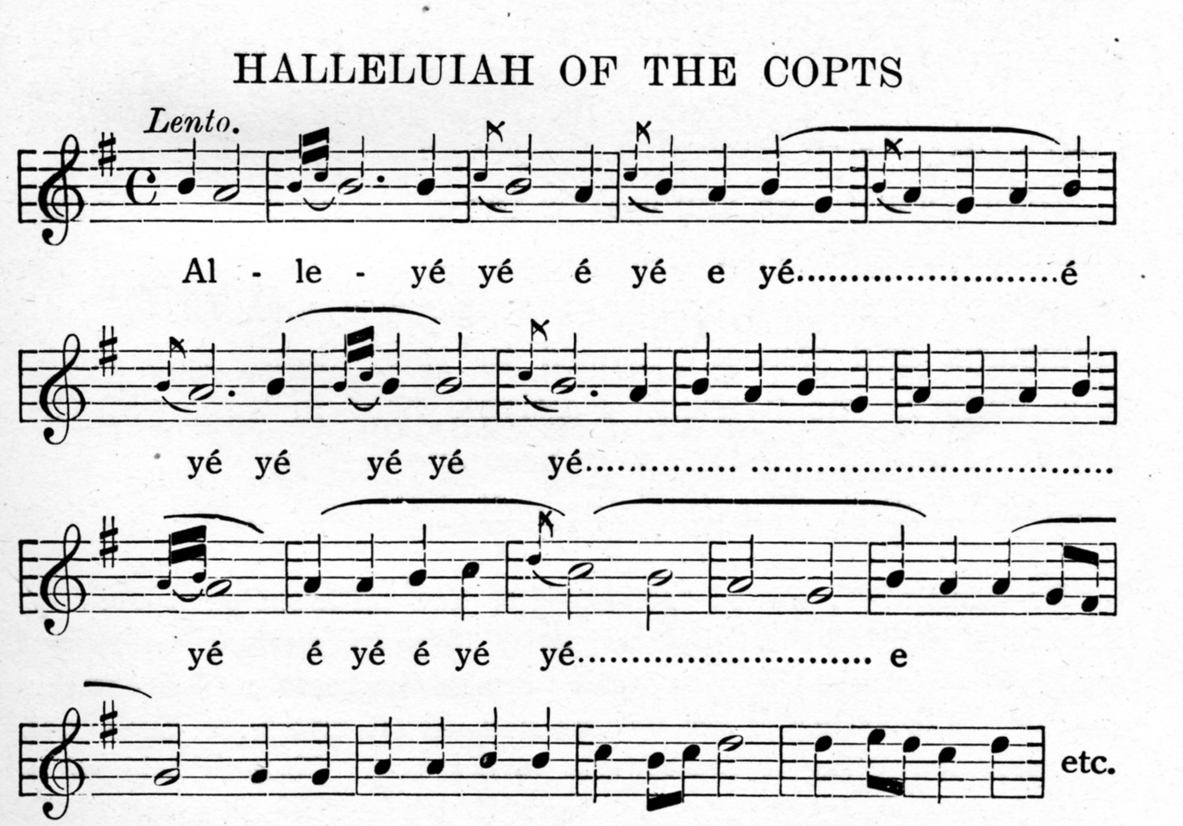

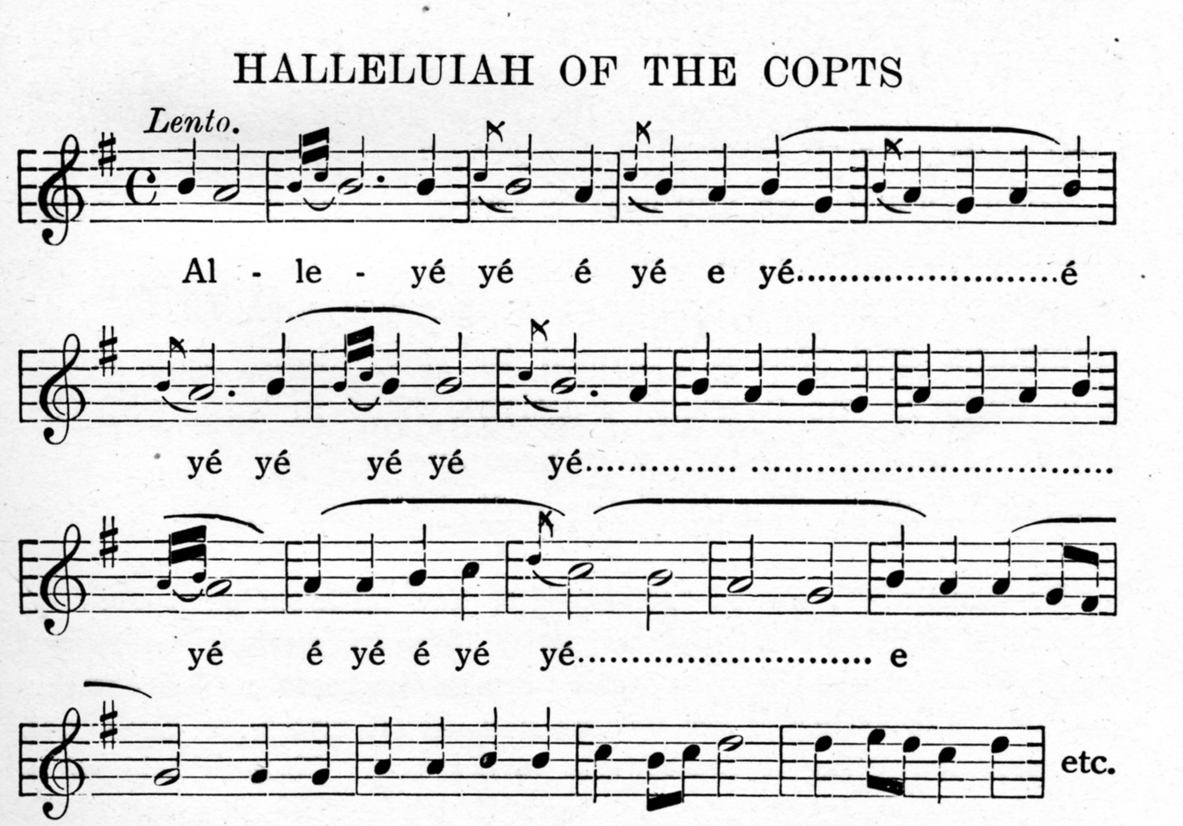

The Copts are a Christian people, descendants of the Greeks, Nubians, and

Abyssinians. The Coptic Church is said to have preserved the most ancient and primitive Christian ceremonies.

|

On the Gold and Slave Coast every god of note has his

own individual dance. The Negroes of the Gold Coast believe in an indwelling spirit, the Kra, or soul; there are

two souls, one of which abides with the body at death

while the other departs to the land of the dead. Among

the indwelling spirits are those which are believed to inhabit trees. A. B. Ellis gives the following terms used for

the gods: Orisha (Yoruban), Bohsum (Tshi-speaking

people), Vodũ and Edrõ (Ewe-speaking people). The

term Vodu is derived from võ (to be afraid), or from võ (harmful). Edrõ from drõ (to judge).2

Vodu (voodoo or vaudoo) is the term used at the present time in the West Indies and Haiti, but the superstition long remained among the Negroes and Creoles of

Louisiana and was introduced in their dance and song.

The deity is the python. Festivals held in honor of the

accepted god of wisdom were accompanied by singing and

voodoo dancing. The crocodile, called Elo or Lo, had neither

priests nor temples; but when canoeing, the canoe men

chanted to its praise.

The use of music in healing is very old. In the psychic

life of the African, connected with the Bori religion of

the Sudan, we find "songs of exorcism" which are performed with various idolatrous methods of healing those

whom they believe to be possessed by spirits. In the Nile

countries, treatment by tones of the fiddle and the drum

continue for seven days when the patient is declared

cured. The Goye-player, a fiddler, and in some places a

guitarist, plays an important part in these ceremonies.

Only outside the Sahara was the drum used.

The player chants the names of the various alledjenu

(spirits), because each deity has his own particular theme

in harmony. The proceeding is likened to a duet or musical dialogue between flute and drum, a combination still

in use. The combined treatment of religious observances

and music, and sacrifices of rams, ending with dancing,

is a part of Shango worship.3 We hear much today of

the therapeutic value of music, spoken of as being in a

new, experimental stage, and yet we find uncivilized people practicing the art in the days of long ago.

Dancing clubs representing figures of the god Edju,

which is worshipped in North Yoruba, are found made of

ivory and of wood. This god dwells at the cross-roads

where are placed in his honor small clay cones, around

which dances and processions take place at certain annual

seasons.

The early religious belief of the Egyptians — that of

many gods — has been preserved in their hymns. The exceptional monarch, Akhenaten (or Aknaton), 1450 B. C.,

father-in-law of Tut-Ank-Ahmen, devoted himself to the

worship of one god and believed that god was manifested

in the rays of the sun. His Hymn to Aten has been published in full by Prof. Breasted, Mrs. A. A. Quibell and

other Egyptologists. Of spiritual and lofty thought his

poem began:

"Beautiful is thy resplendent appearing on the horizon

of heaven,

O living Aten, thou who art the beginning of life. When

thou ascendest in the eastern horizon thou fillest

every land with thy beauties.

Thou art fair and great, radiant, high above the earth;

Thy beams encompass the lands to the sum of all that

thou hast created.

Thou art the Sun; thou catchest them according to their

sum;

Thou subduest them with thy love."

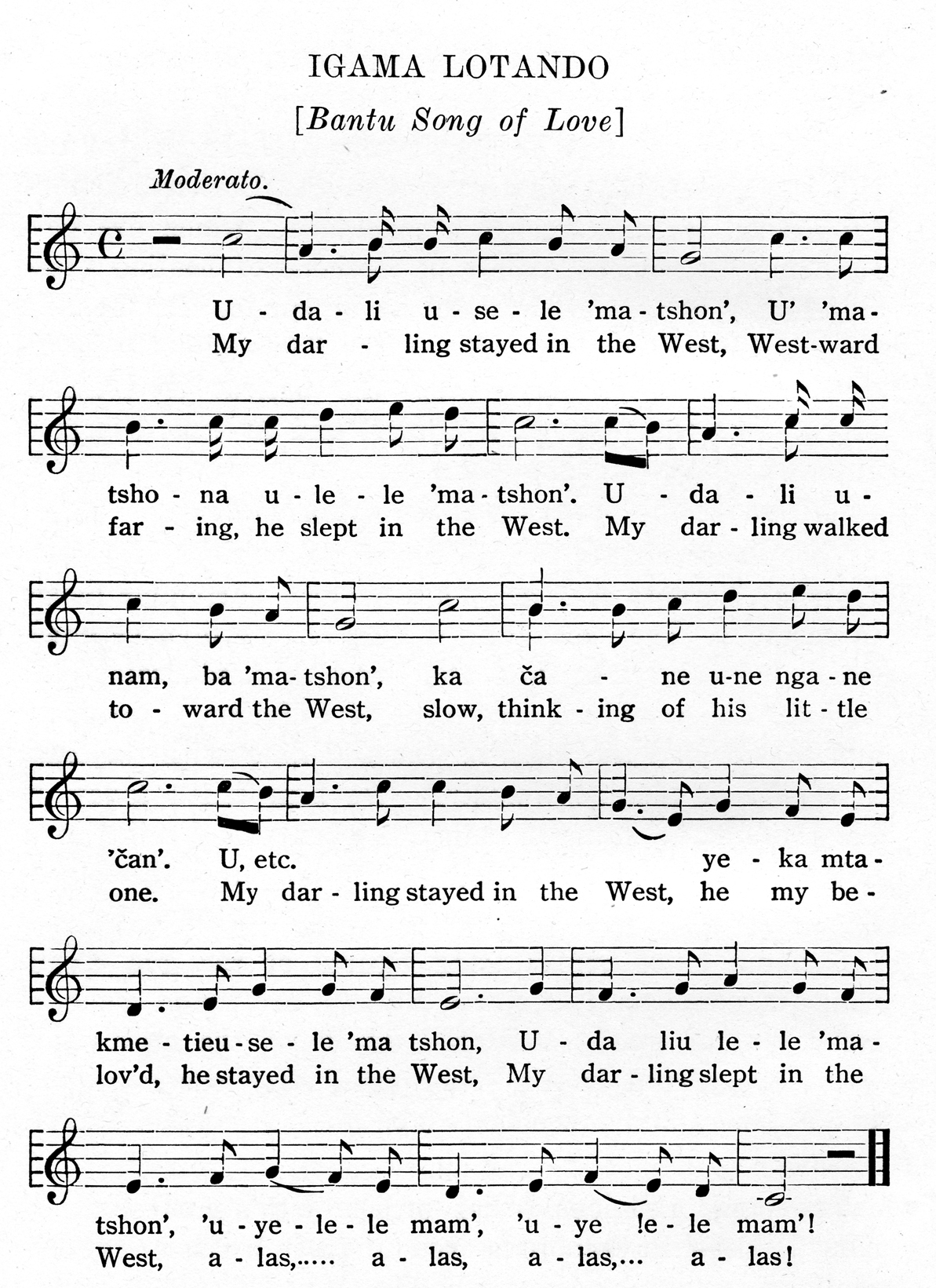

The land of Osiris, "the god of the dead," is believed

by the Egyptians to be that of the West. The Zulus use

the word "west" as the name of this mysterious spirit-land. The word comes from the verb "tshona" to sink or

die away, while the complete expression "He went West"

— Zuva lake la vila — means his sun has set. The expression is common to other African languages. C. Kamba

Simango of East Africa gave the author the following

Zulu expression of like import: "Zuva rakwe rabira" —

"I langa lake li tshonile."

We find that the phrase "He went West" which came

to us from the World War, was taken from the African

soldiers. Natalie Curtis-Burlin in Songs and Tales from a Dark Continent quotes a Zulu love song, a song of grief

which Simango also sang to the author of this volume:

"My Darling stayed in the West, Westward faring, he

slept in the West. Alas! Alas! Alas!"

|

The expression "he has gone West," referring to the death of a soldier, in the lately ended World War, came from the singing of this folk song by African soldiers.

Sung to the author by Kamba Simango of Portuguese East Africa.

|

Among other songs which Mrs. Burlin recorded through

Madikane Cele of South East Africa and Kamba Simango

of Portuguese E. Africa, is a song which is supposed to be

sung as a farewell by the Familiar Spirit which has entered the Nyamsolo, diviner, when treating the sick.

The folklorist likens the condition of the diviner to the

trance of the spiritualistic medium of modern times.4

Many of the African folk songs express implicit faith

in the god while a host of their old legends attribute

magical power to music. From the ancient races of the

Mediterranean to the Kaffir of the South, from Mohammedanism to Shâmânism, through blend of races and

influence of religion, Africa presents the greatest vestiges

of her past — music and song.

There is unmeasured length from the practised contortions of the voodoo worshippers of heathen tribes, to the

rhythmic grace of a Ballet Russe, but the distance is not

so great from the ancient dances woven around an incident of pre-historic times to the interpreters of the Scherazade Tales. Alike in spirit, both are indicative of

the storyteller's "Once upon a time" —

"When the sun goes down, all Africa dances." Such is

the popular saying of the explorer and traveller. The

dance is interwoven with every conceivable custom. While

the licentiousness of some of the primitive dances have

been commented upon by certain spectators, the society

dances of the present, tolerated and accepted by the most

highly civilized nations, are less than a stepping stone

from the gyrations of a heathen people.

The earliest traces of music in native Africa are found

in the dances of worship. No matter what form of religious cult was practised, music took an important part

in its ritual. Many of the dances are connected with the

rites concerning the mythological gods. One of the most

interesting of the worship dances is the fire dance, performed at the great seven-day festival accompanied by

drum-beating of the Batta drummer. A mystic dance

practised by the Tshi-speaking people on the Gold Coast,

between the Assini river and the Volta, is part of the

ceremonies connected with the worship of the tutelary

deities.5 The Dako Boea Dance, to the Great Father, the

sacred deity of the Nupe tribe in West Africa, in which

the presence of the Great Spirit is invoked, is no longer

practised, for the custom has been forbidden by the

missionaries.6 A mystical dance of the Bushmen is called

nagoma by the Basutos. When a man is ill, this dance is

performed around him and is continued throughout the

night by men and women who follow each other. The

dancers are supposed to have supernatural power.

Among Ewe tribes, dancing is a special branch in the

education of both priest and priestess. They must be very

proficient in the art, and practise for months in order

to acquire the necessary agility. The boy and girl recruits

who have studied three years for the priesthood, dance

before the King at the Annual Custom. During their

novitiate they are taught the dances and chants peculiar

to the worship of the gods. The dances among the Ewe

tribes are always performed to the sound of drums. The

addugba is used for the ceremonies. Another dance

connected with the priesthood is that of the Tshi-speaking

people of the Gold Coast. When new members were tested

for the priesthood in Freetown, the following ceremony

took place: The company drums were used, and as the

drummers struck up their beat, youths and men raised a

song in honor of one of the deities of the company. Just

as there is a special hymn for each deity, which is sung

to a special beat of the drum, there was also a particular

dance for the same; the priest is under the influence of

the individuality of a tutelary deity of the company, as

soon as he places his hands upon the drum. In honor of

this deity, drums give out the rhythm, the singers begin

to chant and the priest performs a dance.7

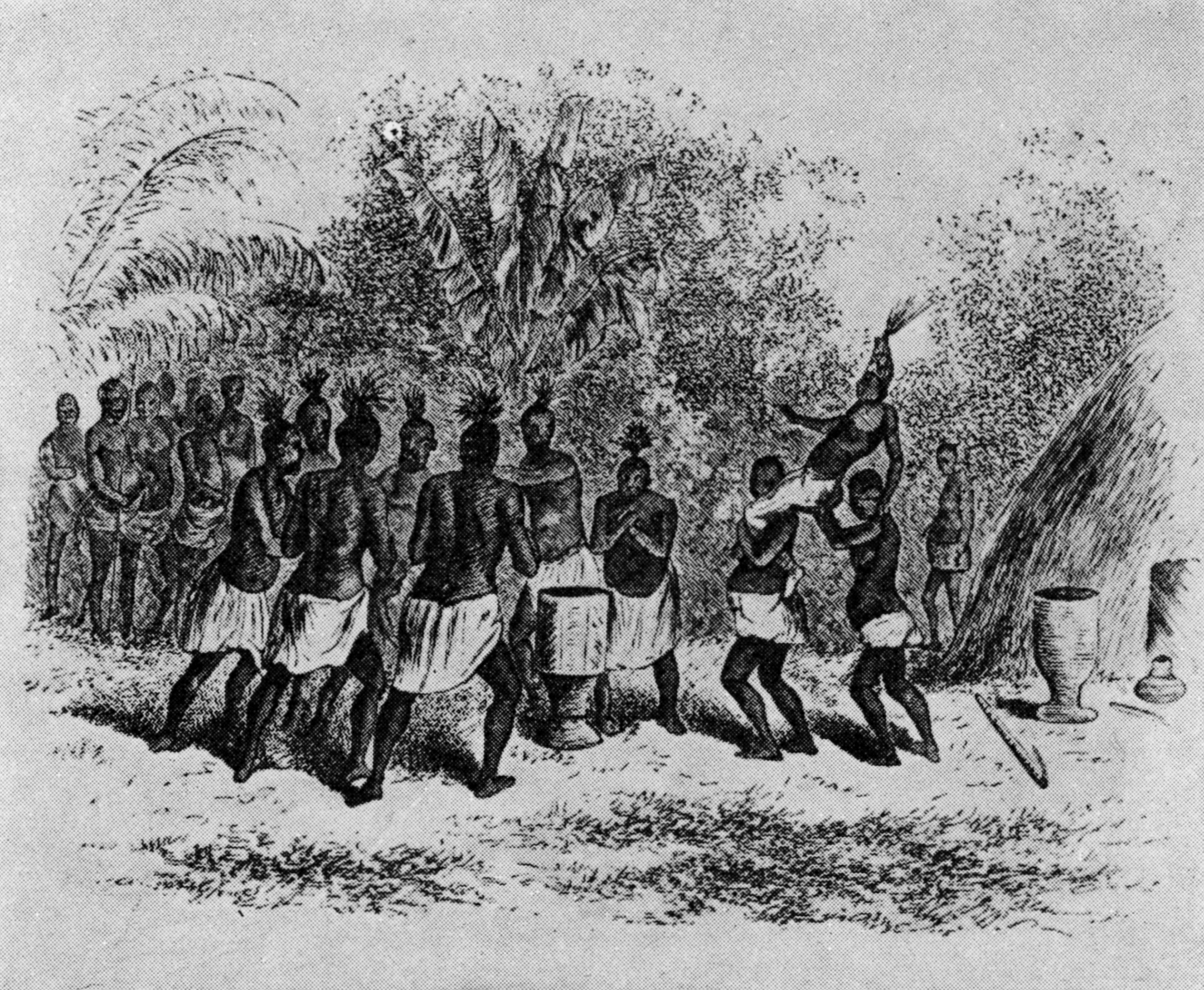

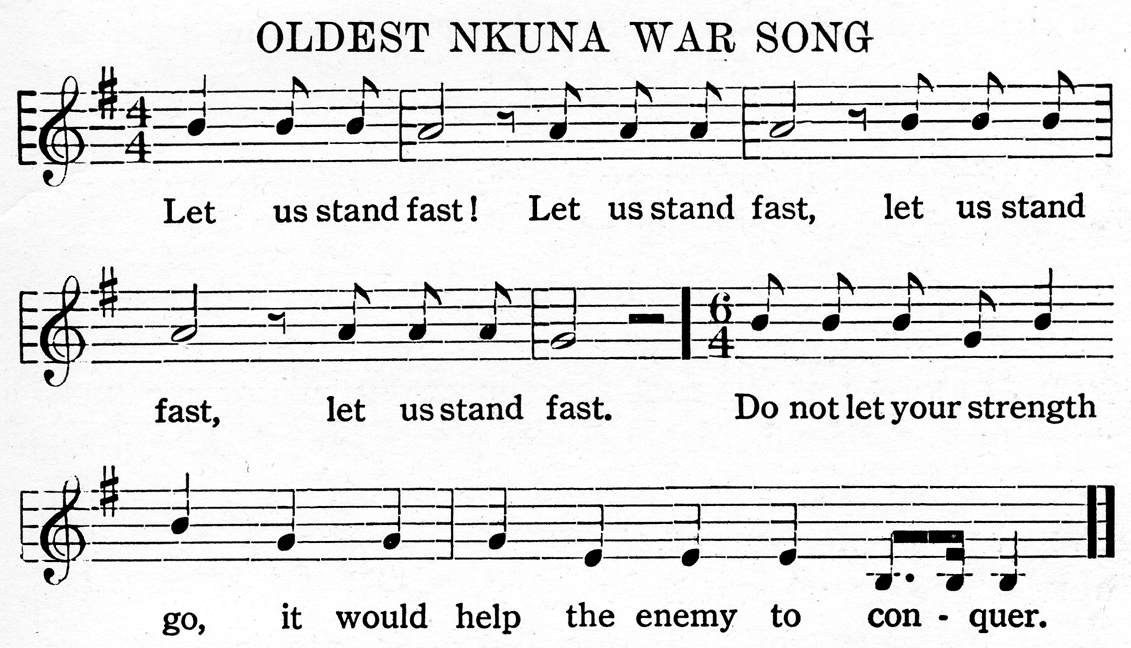

The war dances are the finest of the African dances, and

perhaps the most important of these is the Dance of the

Spears. Usually, when the dances are about to begin, they

are heralded by sounds from the fiddle (goye) and guitars (molo), accompanied by the drums. When the

drums are grooved, they are held before the player who

scratches them with his nails as they are turned around.

There is a spear song and dance that comes from the

Thonga of South Africa.

"Let us stand fast! Let us stand fast!

Do not let your strength go,

It would help the enemy to conquer."8

|

Dances connected with ceremonies of state are attended

by elaborate preparations and magnificent display. Of

great event are those that are held at the coronation of

the kings. In West Africa, after the conclusion of the

coronation festivities, a dance is held in the open square

in the center of the town. The best singers, clappers and

other musicians come to take part, led by the Zobas or

"Country Devils," the best dancers of the country. One

to three hundred trained women dancers go through many

intricate figures.9

There are also festival dances. In the territory of Sierra

Leone we find what is known as the Hammock Dance,

which is one of a number of festive exercises. Another festival dance known in British West Africa is called the

ugowa and is danced only at the high festivals of the

Zanzibar. Thought to be of magical power, the instrument

called kinandi-kinubi is brought out and borne about

the town while the dance is performed to its accompaniment.10 A dance of the Kafirs which continues from sunset to sunrise is the ugoma. It is accompanied by a

large kettle-drum which receives its name from the dance.

Performed to drums of like name, is the ukonje which

is danced by the Mpongwe, the Gaboon and the French

Congo tribes. The Bushmen are particularly fond of

dancing by moonlight. They possess a variety of dances

pertaining to social customs, each of which has its appropriate chant. One dance imitates the actions of different animals.11 Among a variety of dances of West

Africa is the ziawa which is accompanied by song.

Another is the mazu in which there is much gesticulating with the arms. A third, the timbo, is the common

native dance. On fine evenings, it is customary for professional strolling singers and dancers to go from house

to house dancing and singing for the amusement of the

wealthy. One of their song-dances is named the ngere.

In all civic ceremonies and social institutions pertaining to christening, marriage, death or the political life,

the dance ranks in importance with the feast. It has place

in the training which the youth receive in the societies

of learning in West Africa — the Beri and Sande institutions.12 At the close of a young man's education in one

of the societies, classified as these institutions are by age,

he is quite likely to meet the girl of his choice, but a long

courtship ensues before the marriage takes place. After

the season of probation is over, the wedding is solemnized.

In the Bantu country, South Africa, a wedding dance is

known as the khana. The dance consists of leaping and

springing up and down with a quivering of the body.

The leaps from the ground are made exactly upon the

certain note when repeated. This dance extends over the

period of the celebration which lasts as long as the bride-groom's relatives provide oxen for slaughter. There are

intervals, however, for feasting and for rest. The movement of the men in the dance is different from that of

the women. Their mode of dress differs, of course, according to the particular tribe.13 The native social dance,

bamboula, is opened with the beating on the tom-tom.14

The perfection of the African dance rhythm has produced comment from all those who have been privileged

to witness the performances. It is well marked, always

emphasized by the instruments. The time signatures of

2/4 and 4/4 are found oftener than 3/4 or 6/8.

Dancing was the principal part of the songs called "The

Songs of Ronga." The dances were performed after harvest. They were taught to the boys and girls, who became proficient in them. Now no longer practised, newer

dances having taken their place. The Zulu mudjatu and

muthimbo became popular only in turn to be succeeded

by the shiloyi in which the performers sit and execute

movements in imitation of boat rowers.

It is a significant fact that the youth of the coast are

summoned by the chief to take part in the dances, and,

while it is not obligatory, it is expected. This causes the

conjecture that here perhaps is the beginning of a native ballet!15 A few years ago, Adolph Bolm, the Russian

Mime, of the Imperial Ballet School in Petrograd, expressed a desire to stage a Negro ballet with people who

had a perfect understanding of that race. He believed

that the effect would be thrilling. From the mythological

history as expressed through the medium of the African

dance, a ballet, replete with the imagery of the people,

may yet be evolved under patronage of chiefs and kings.

[CHAPTER II]

Notes, Chapter I

[Page 2]

1 Dr. Merlin W. Ennis, archaeologist and anthropologist for the

American board for foreign missions, 30 years working in Portuguese West Africa, has been excavating in the heart of the African

jungles. Excavating at the Cunene and Kukai rivers, he discovered

pyramids indicating a pre-historic civilization. Natives told of a

drum in the shape of a hyena, reputed taken from a royal tomb.

(1933.)

2 Ellis, A. B., The Ewe Speaking Peoples, p. 29.

[Page 3]

3 Frobenius, The Voice of Africa, Vol. II, pp. 524, 562, 567, 570.

[Page 6]

4 Curtis-Burlin, Natalie, Songs and Tales from a Dark Continent, pp. 24-145.

[Page 7]

5

Frobenius gives a vivid description of one of the mystic dances

in the land of the Muntshi, a pagan people and a freedom-loving

nation very much feared by other tribes. Having secured the good

will of the people, he was allowed to witness one of the mystic

dances.

"Then — what is that peculiar looking ornament shining on that

beautiful woman's neck? What a curious, bird-shaped hairpin it is

which she is putting into her neighbor's head-dress! What extraordinary bronze spirals decorate the foreheads of the men! How

beautifully forged the spear-heads and the iron rings and chains!

Just look at that beautifully shaped bronze tobacco pipe; there is

no doubt but that we are among a people whose art and industrial

development stands high indeed.

"Evening falls . . . A huge wooden signal drum is pushed into

the middle of the Square, little field drums as well as flutes and a

kakatshi trumpet taken as a war trophy from the Fulbes, are

brought along too. The moon goes up. The folks have foregathered

in their hundreds from the surrounding villages, laughing and

chatting. The first taps of the drum resound: the flutes join in

and develop a charming air to which some men dance a measure.

All the hundreds assembled begin to move their shoulders and hips.

The time gets quicker — the steps get quicker and stronger. More

flutes join in until the whole of the vast, old, primeval forest

re-echoes with the tunes and the glad shouts of the joyfully excited throngs of the human beings who madly whirl about in circles.

"Separate dancers perform here and there. The melodies are

changed. The musical sense tries to obtain fresh combinations and

variations of rhythm. The shrieks of the women grow sharper and

sharper: the shouts of the men become louder and wilder. A passionate excitement I have never before in all my experience witnessed seizes the crowd. We enjoy the sight till far into the night."

Frobenius, The Voice of Africa, vol. I, p. 214.

[Page 8]

6

"Formerly, those who took part in the dance were masked and in

appearance evidently not unlike the "devils" of the early carnival

days in the French West Indies. Two of the masquers, on stilts,

many feet high and draped in flowing robes, dance along together.

Those who danced around these figures were in their normal dress,

except the upper part of the body was unclothed.

"A striking feature of the dance were the devotional songs chanted

in rhythm to clapping hands by a group of women who gathered

about the tree-trunk. The burden of their prayers to the mighty

Dako-Boea was that they might be blessed with motherhood. In

front of the singers danced a single figure drawn from the group

that danced in ectasy before the symbol of their ancient god.

"It is remarkable how the dances and songs of Africa lead to

ethnological facts. Tracing a bit of melody, one finds an old legend

and through the myth or folk-tale the prehistoric life of a people

is discovered. In 1874, amid the highest mountains of South Africa

(the Maluti) and the overhanging rocks that form caves, George

Stowe and J. M. Orpen found pictures of dancing figures. Of their

mythological significance, Dr. Bleek, a scientist, wrote that it

was "an attempt at a truly artistic conception of the ideas which

most deeply moved the Bushman mind." Frobenius, The Voice of

Africa, vol. 1, p. 216-7; Dr. Bleek, Folk-Lore, June 30, 1919, p. 155.

[Page 9]

7

For the benefit of many writers of "African Dances" in art-music, the following description may not be amiss:

"The drummers at once struck up the rhythm. . . . After a few

moments the priest stopped (his dance) and putting his head on

one side, indicated that the god who now possessed him could not

hear the song in his honor — the singing was not loud enough or the particular drum rhythm was not sufficiently marked. — The song and drumming stops; a new start is made. This is repeated until

satisfactory; then the priest dances furiously, bounding in air,

tossing arms, but keeping perfect time to rhythm of the drum.

This must require long practise and great endurance, for the

dancer has naked feet and no springy board of floors, but the inelastic earth. Another god enters him and again wild dancing,

and then the utterance of oracular sentences." Ellis, A. B., Tshi-speaking People of the Gold Coast of West Africa, p. 138.

[Page 10]

8

Henry M. Stanley glowingly described this as a phalanx dance of

great volume and color, "The phalanx stood still with spears grounded until at a signal from the drums, Katto's deep voice was heard

breaking out with a wild triumphant song or chant, and at once

rose a forest of spears high above their heads, and a mighty chorus

responded. . . . There was accuracy of cadence of voice and roar

of drum." Faces were turned upward, heads bent back; right arms

shook clenched fists on high as every soul was thrilled by martial

strains. Then heads turned and bowed earthward with thought of

the desolation of war-ridden lands and widows' cries. But again

heads were tossed backward, "bristling blades flashed and cracked

and the feathers streamed and gaily rustled. There was a loud

shout of defiance and such an exulting and energising storm of

sound that man saw only the glorious colors of victory, and felt

only the proud pulse of triumph." Stanley, Henry M., In Darkest Africa, vol. I, p. 436.

[Pages 10-12]

9

"Bowditch writes of the Pyrrhic dance which was performed at a

reception given him in the Spring of 1817. He gives a vivid description of barbaric splendor:

"Met by a crowd of 5,000 people, largely warriors, who greeted

the party with martial music, they were halted in order that they

might witness the Pyrrhic Dance which was performed in a center

of a circle of warriors, where flags, English, Dutch and Danish

were waved. The Captains held spears in their left hands, while

affixed to a long chain held between the teeth and right wrist, was

a scrap of Moorish writing.

"The bands, of which there were more than one hundred, were

composed principally of horns and flutes with innumerable drums

and metal instruments. Each band had its own peculiar tune for

its particular chief. One hundred or more large umbrellas were

sprung up and down by the bearers and as the canopies were made

of scarlet, yellow and the most brilliant silks and crowned with

crescents, pelicans, elephants' ears and swords of gold, all of

various shapes, with fantastically scalloped valances, the startling

and brilliant effect may easily be conceived.

"The State hammocks were raised in the rear. Large drums,

supported on the head of one man and beaten by another, were

bound around with the thigh-bones of their enemies and ornamented with their skulls. Kettle drums were scraped with wet

fingers. Wrists of the drummers were hung with bells and peculiar

shaped pieces of iron. There too, were smaller drums — prolonged

flourishes of the horns and ever the deafening beat of drums.

"The dance was witnessed by many native dignitaries who were

of the king's escort — the Chamberlain, the Gold Horn-blower, the

Captain of the Messengers, the Captain of Royal Executions, the

Captain of the Market, the Keeper of the Royal burial-ground and

the Master of the Bands."

And then, Bowditch continues, "The royal stool, entirely cased

in gold, was displayed under a splendid umbrella, with drums,

'sehukus' (native stringed instruments), horns and various musical

instruments cased in gold, about the thickness of cartridge paper.

The swell of the bands gradually strengthened on our ears, the

peals of the war-like instruments bursting upon the short but

sweet responses of the flutes."

Those who wish local color in their pageants, such as has been

given in recent years depicting visually the history of Africa, might

profitably turn to the vivid pictures of royal settings of the

African dance as given years ago by Bowditch. — Bowditch, Mission from Cape Gold Coast Castle to Ashantee, pp. 246, 255. 1819.

Occasionally, the King takes a part in the dance. Schweinfurth

was privileged to witness in 1870, a performance by Munzo, King

of the Monbuttoo — (According to "scientific observations," he

makes the deduction that the Monbuttoo are of Semitic origin, most

thoroughly impressed upon their countenance, to which in particular, the nose very much contributes.) Describing the dance,

this traveller writes:

"First of all a couple of horn-blowers stepped forward and proceeded to execute soli upon their instruments. These men were

advanced proficients in art, and brought forth sounds of such

power, compass, and flexibility that they could be modulated from

sounds like the roar of a hungry lion, or the trumpeting of an

infuriated elephant, down to the tones which might be compared

to the sighing of the breeze or to the lover's whisper. One of them,

whose ivory horn was so huge that he could scarcely hold it in a

horizontal position, executed rapid passages and shakes with as

much neatness and precision as though he were performing on a

flute."

Following the professional singers and jesters, the king himself,

takes part on the program, making a speech and afterwards assuming the role of a conductor. The baton used was a hollow rattle.

After a return visit to Schweinfurth's camp, the king arranged a

feast in celebration of a successful raid over the Momvoo. The

festival reached its climax mid-day when the king, himself, danced

in the presence of his wives and courtiers. It was held in the noble

saloon, a royal hall which the explorer calls one of the wonders of

the world. George W. Ellis, Negro Culture in West Africa, p. 72.

[Page 12]

10

Rose, Algernon, Internat. Music Soc. Journal, Priv. Coll. Afr. Instr., p. 60 — Nov., 1904.

11

Theal, Yellow and Dark Skinned People of South Africa, p. 47.

[Page 13]

12

Of the dance of the Bondu, the exclusive women's secret society

of Sierra Leone, Newland says:

"As I was permitted to be present at one of these affairs, I

can assure my readers it is almost as artistic and certainly more

quaint than an Alhambra ballet. The tee-tees, or young girls, are

adorned with bracelets of palm leaf fibre encircling the arm and

wrists, their body nets being made of cotton to which are attached small iron plates jingling as their owners dance.

"The dance is sometimes weird and fantastic, especially the

'devil dance,' and is accompanied by the inevitable 'sangboi' or

drum, and a 'sehgura' or kind of guitar made from a hollowed

gourd with seeds threaded on strings to make a sharp, metallic

sound. At the end of the dance, women spectators rushed into

the circle and embraced the dancers." — "Negro Social Life in West

Africa," Journal of Race Development, Vol. IV, Oct. 19. H. O.

Newland, Sierra Leone, p. 125.

A mask dance of the Ronga and Thonga tribes of South Africa,

is called the "Mayiwayiwane." The mask has its traditional significance. Frobenius found in West Africa that "reverential remembrance" is embodied in a like ceremony of Nupes — "When

Egedi, the founder of the young Empire came into the country

some 475 years ago, the Dako-Boea, a mask of several yards in

height, stood upon his canoe. When Gushi, one of the oldest rulers

of the land died, his corpse vanished and the mask referred to

rose up where it had lain — the associated idea of growth into manhood, the unfolding of masculinity out of the neutrality of childhood." — Frobenius, The Voice of Africa, Vol. II, p. 395.

[Page 14]

13

A description, however, of the garb of armed attendants of a

chief in southern Africa who took part in the dance, is interesting:

"Their figures are the noblest that my eye ever gazed upon,

their movements the most graceful and their attitudes the proudest.

Standing like forms of monumental bronze, I was struck with the

strong resemblance that a group of Kaffirs bear to the Greek and

Etruscan antique remains, except that the savage drapery is more

scanty and falls in simpler folds; their mantles, like those seen on

the figures of the ancient vases, are generally fastened over the

Shoulder of the naked arm, while the other is wholly concealed; but

they have many ways of wearing the carosse. In the dance, they

threw their carosses off and forming a semi-circle, bowed their heads

low and bounded upwards with a spring. Our interpreter sung a

Kaffir song which was soft and pleasing, for their language is in

an uncommon degree musical." Rose, Cowper, Four Years in

Southern Africa, p. 84.

14

"Pierre Loti, Le Roman d'un Spahi, chapter II.

[Page 15]

15

Junod, Henri A., Life of a South African Tribe, pp. 167, 181.

CHAPTER II

AFRICA IN SONG

LEGEND AND

FOLK

TALE —

SINGING IN

GENERAL —

EXTEMPORANEOUS

SONG —

HARMONY AND

RHYTHM —

TRIBAL

CUSTOMS AND

SONGS —

HARMONY AND

FORM —

PRESENT-DAY

CHARACTERISTICS —

NATIVE

AFRICAN

MUSICIANS AND

OPERA.

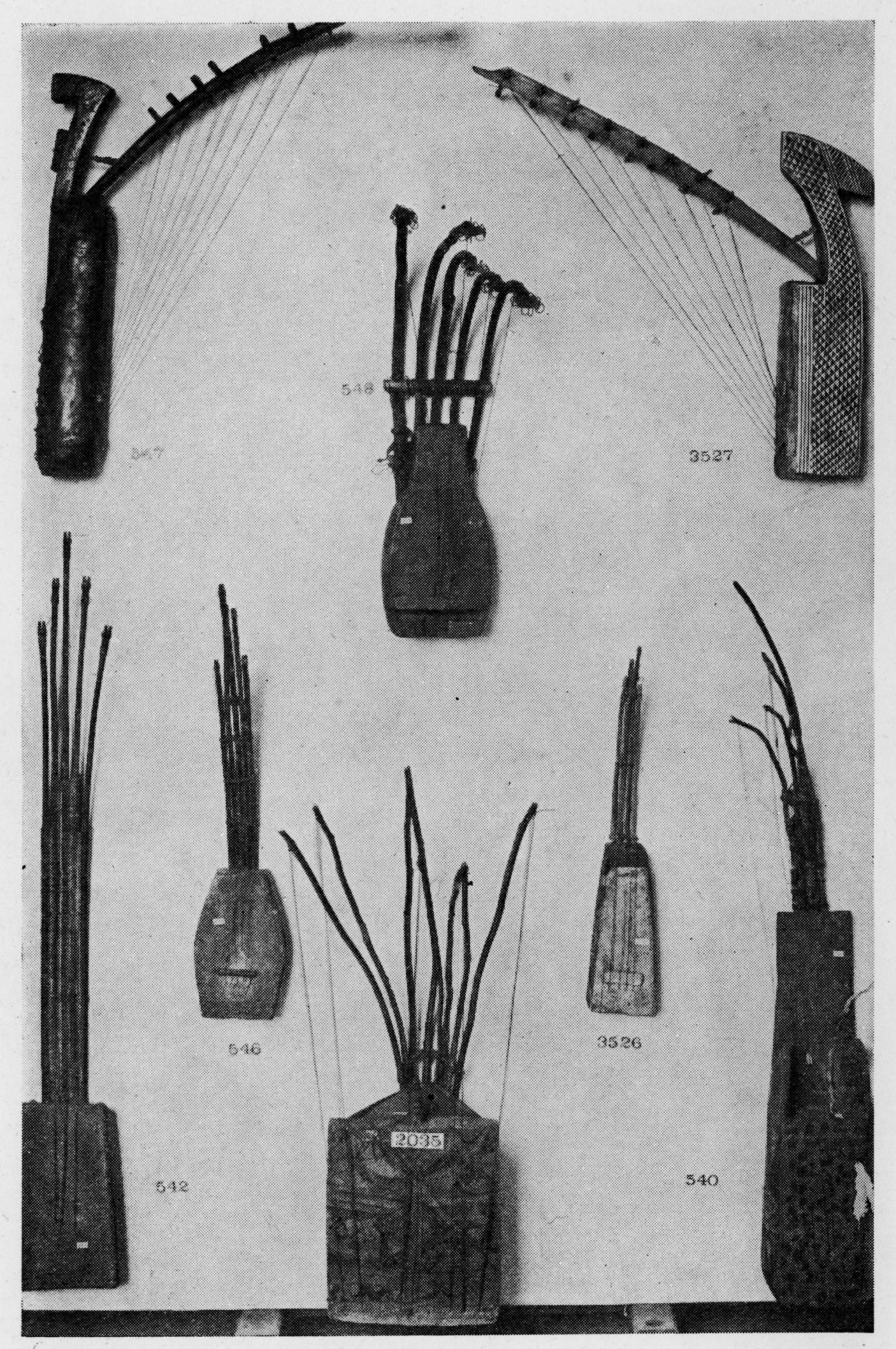

1: Drums;

2: Stringed instruments; Harp-type-psaltry, Lute and Bow-played;

3: Vibrating Sonorous Bodies, Marimba, Flutes, Trumpets, and Horns;

4: Lesser instruments.

We have seen how the content or significance of the

African dances may be traced in the legends of that continent. In like manner, many of the songs are found based

on a fable or folk tale, or descriptive of a social custom

of a tribe or nation. Here, through music, we find a related myth that has existed for centuries. Had the explorers of Africa been musicians as well as archaeologists,

they would have appreciated the mighty ally of song

which was at their hand, and their historical researches

would have been expedited.1

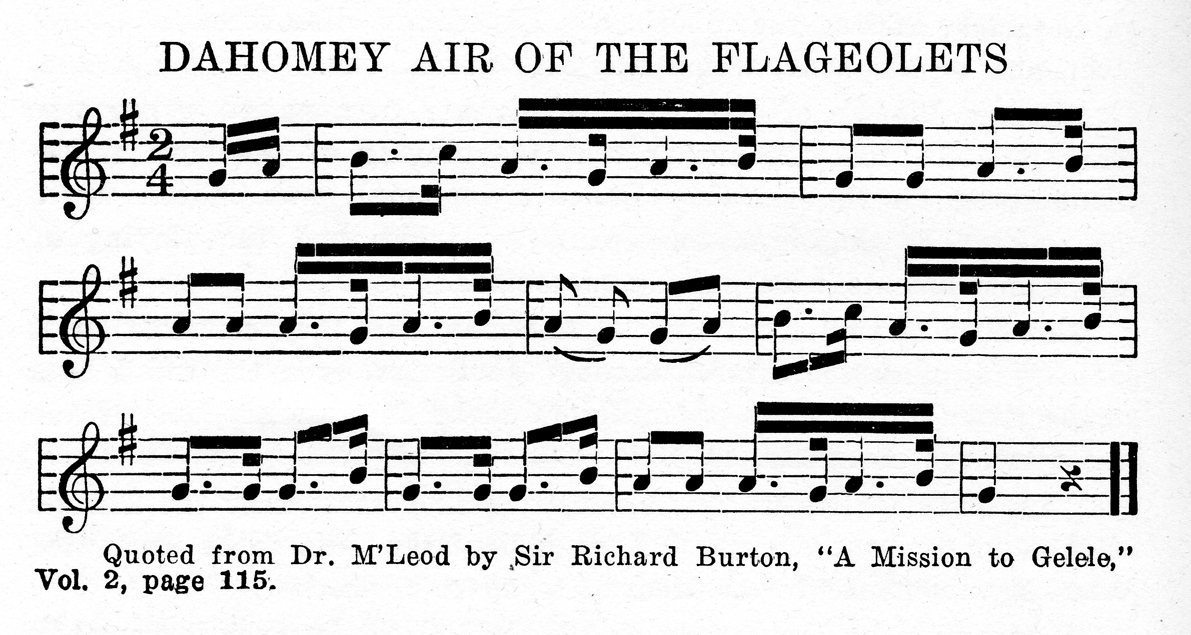

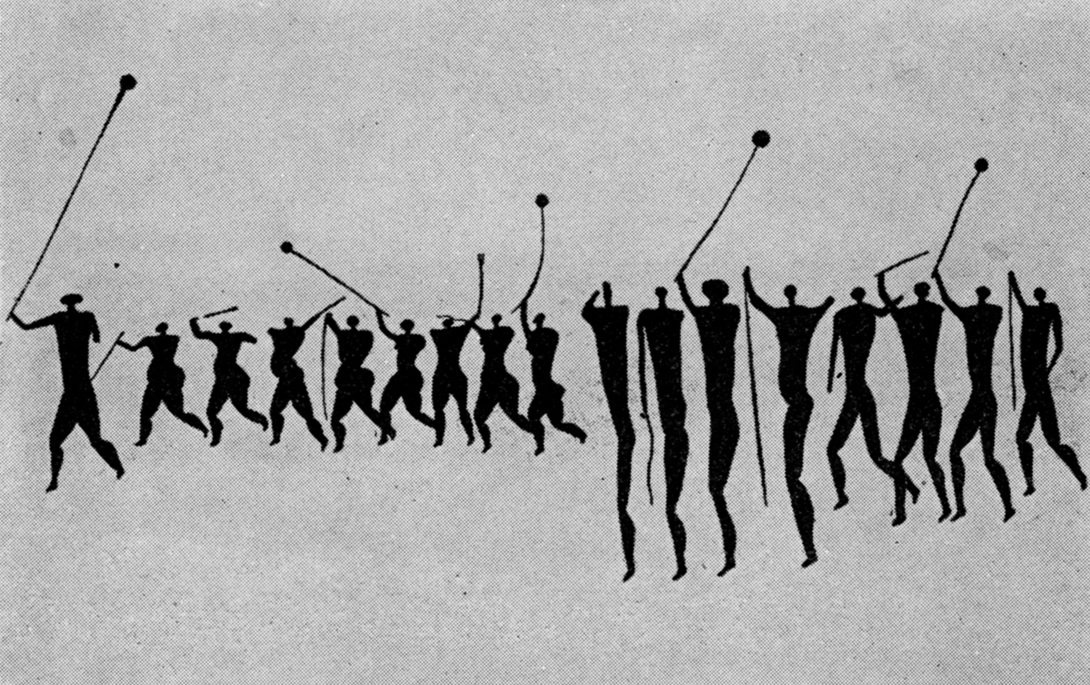

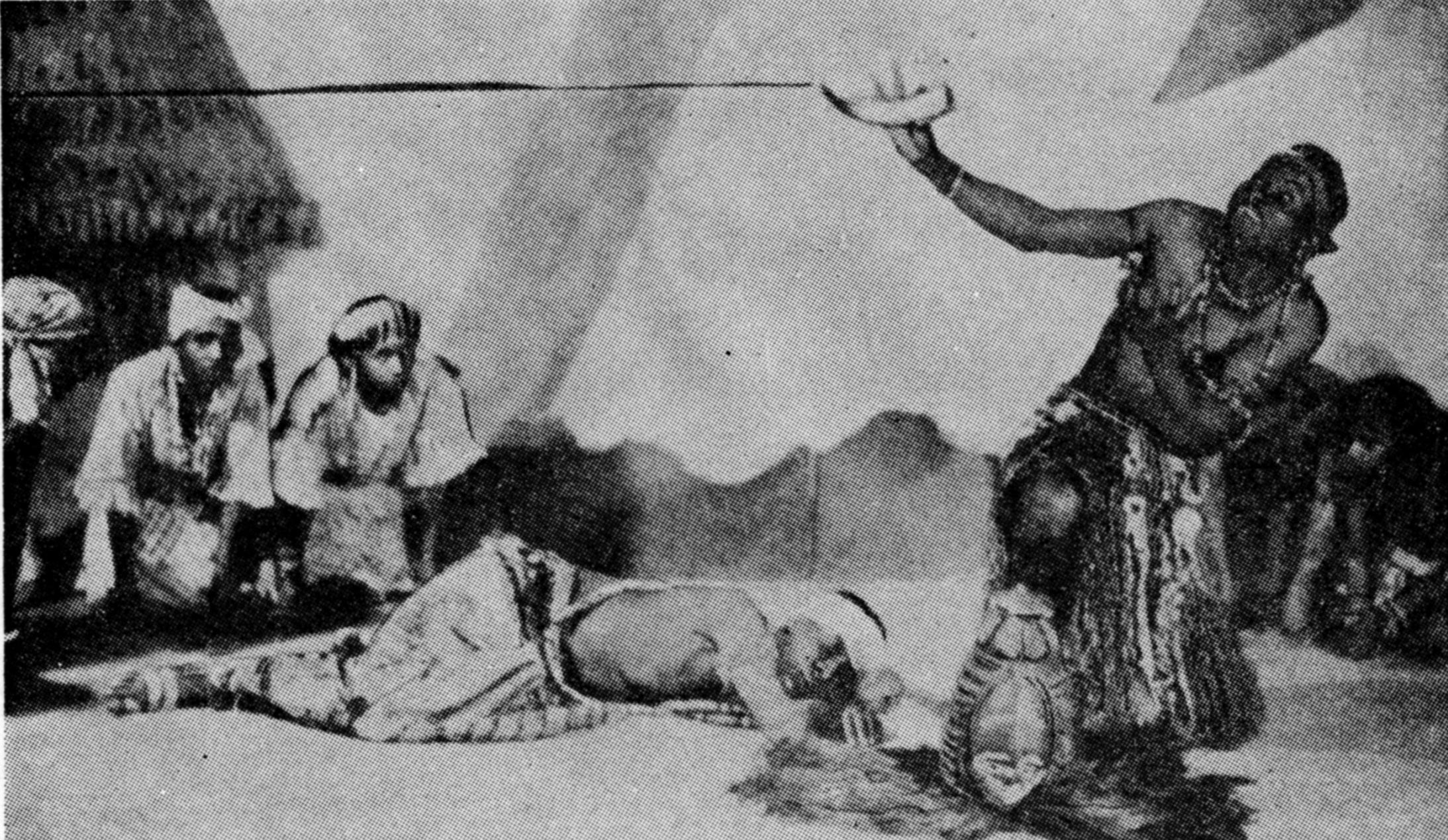

THE AFRICAN DANCE

AN AFRICAN PAINTING

We know how the animal stories of Negro-Africa have

been assimilated in American literature by Joel Chandler

Harris in his Uncle Remus Stories. Many episodes of the

"Romance of the Hare" alone are found in Bantu folklore. "Brer Rabbit" as the American version of the

African hare is an emblem of cunning and wisdom.2

Traditions of the Kanuri people are handed down from

generation to generation by a school of sages known as

"kogolimas" or story-tellers. Grégoire says, "The Negroes

have their troubadours, minnesingers and minstrels, named

Grals, who attend kings, and praise and lie with wit."

A peculiar class of professional musicians which may be

found nearly everywhere in Africa, make their appearance

decked out in the most startling apparel — feathers, roots

and bits of wood, with other emblems of magical art.

Whenever a listener is discovered, he begins at once to

recite details of his travels and experiences, in a chanting

recitative. The Arabs have bestowed upon them the name

of hashash (buffoons). Wandering minstrels, they are

held in light esteem by the Niam Niam, who call them

nzangah.3

In the Senegal, minstrels who frequent market-towns,

have what is called a song net which is made of a fishing

net. On this all manner of things are tied — tobacco pipes,

bits of china, bird's heads, feathers, reptiles, skulls and

bones, and every object bespeaks a tale. The passer-by

selects an object and asks the price for the song. Bargaining ensues; finally a price is agreed upon and the

purchaser listens to the song. The saying is that when

these singers die, they are put into trees.

The fantastic "song net" reminds one of a home owned

by a very aged colored couple in a Tennessee city of the

United States. It stands on the outskirts of town, on the

road that leads to a well-known college. The trees in front

of the house are literally covered with bits of brightly

colored glass, glazed crockery, parts of broken earthenware and scraps of gayly flowered china — broken pieces of

every known article of a crockery store — and these fastened in the trees! Was it possible that this aged man

and woman were the progeny of Senegal minstrels? No

one could give me an answer to the riddle.

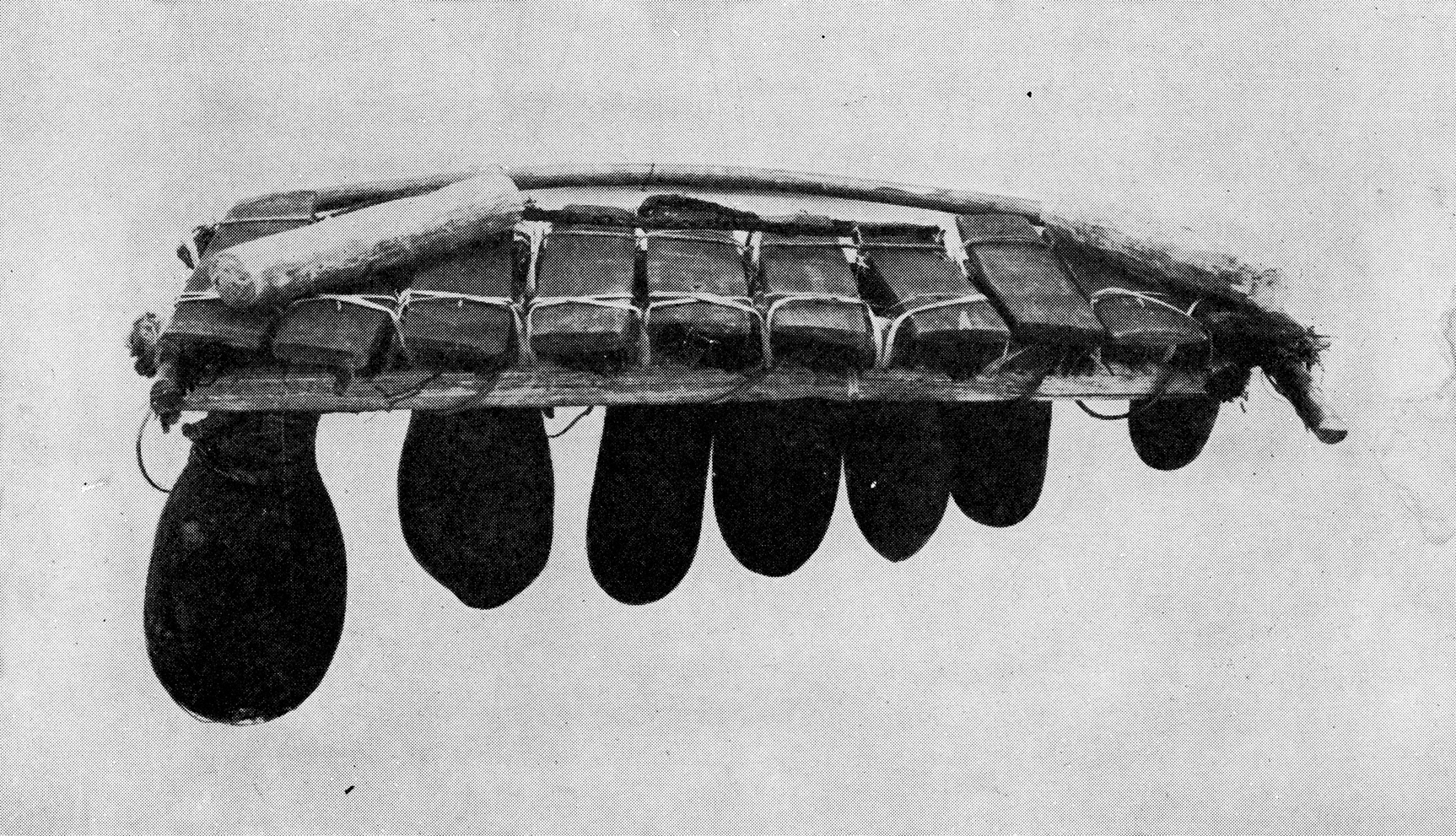

AFRICAN MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

The principal legend of the Songhay, a nation that dwelt

on the Niger, is called the "Originator of the Race."

From it is taken the "song of Nana Miriam," composed

to celebrate the slaying of the Nile-horse. Miriam, the

daughter of Owadia, primal ancestor of all the Sorko

tribes, was taught all her father's magic arts. By her incantations, she killed all the river-horses (the hippopotami), that had destroyed the rice fields. Only one she

spared because it was a Nile mare in foal. Fara Naka

rejoiced, saying, "What a splendid daughter is mine!

Nana Miriam I thank thee!" Then he summoned the Kié

(Dialli or troubadours) singers. He composed a beautiful

song and taught the Kié to sing and play it. All the people in the land, all the singers, all the fishermen, all the

Sorko sang the song of Nana Miriam. And since that

time whenever anyone makes a charm for hunting the

hippopotamus, he always chants over it the name of Nana

Miriam.4

The songs of the Africans are chiefly a species of

recitative or chant with a short chorus. The soloist gives

the melody while a chorus sings a refrain, which at times

are but ejaculations. The chief singer remains standing

while the members of the chorus are seated around him;

and as the melody is given out, they turn to one another,

each improvising in turn. Their power of invention and

improvisation may last for hours. Expert in adapting

song to current events, they indulge in mockery, ridicule,

and sarcasm, or in flattery or praise of men and happenings.

A song of the bridesmaids offers advice which would

occasion great surprise if it were followed. It is from a

collection noted by Mrs. Audeoud in Maputju: "Do not

go with him." The women friends, upon accompanying

the bride to her new home, sing:

"Whither goest thou, mother? Whither goest thou?

They will bring thee the basket full of maize and the fan, my mother!

When thou hast finished crushing it, they will make thee crash it again, my mother!

When thou has plastered the floor, they will make thee plaster it again, my mother."5

Other songs are sung, not only to the bridegroom and

to the relatives, but to the neighbors, for the marriage is

a community affair. All the songs are in a mocking vein,

rather than in a sentimental one.

The writer to whom we are indebted for the information above also tells of certain rites pertaining to the

festival season which is characteristic of the Bantu. One

of a number of the "first fruit rites" says, "The nkanye

is a beautiful large tree, called by the English the Kafir

plum. It bears a small golden yellow fruit which ripens

in January. The first ripe makanye (plural) are gathered

and the sour liquor, which is made from it, is poured on

the tomb of the dead chiefs in the sacred wood, who are

invoked to bless the New Year and the coming feast which

is about to be celebrated. The new beer is first drunk by

the warriors of the army — it has been medicated to prevent them, by a mysterious spiritual influence, from killing any of their comrades during the festive weeks. There

are singing and dancing and rejoicing that the men be

spared in battle."

Before the closing day of the carnival which is almost

in the nature of an orgy, the payment of the tax — a large

portion of makanye — must be made to the chief. The

women, as they carry the wine to the town, sing the following chorus: "Hi! Hi! We seek the hawk! Who soars —

In the sky! Hi! Hi! Who is the hawk? — It is Muzila — It

is Muzila!"6 In this carrier song (there are a number of

them) Muzila, the chief, is compared with the mythical

"lightning bird," — with the hawk that "swoops down

from the clouds."

On the Gold Coast, thanks are returned to the gods for

having protected the crops. As in other sections, there

are apparently two seasons, one in September when the

yam crop is ripe; another (Ojirrah) in December when

the crop is planted. A minor festival, Affi-nah-dzea-fi, is

held in April. The September festival of the Ashanti is

commenced by loud beating of drums.7

Not only in the agricultural life does the native rejoice

in song, but at home as well as abroad, all industrial labor

is lightened by music. Much of the travel in Africa is

carried on by water-ways. Canoeing or rowing is the

favorite manner in which this is done. Wallaschek in

quoting Ernst von Weber, says, "The Balatpi reminded

Weber of Venetian gondoliers or of the lazzaroni in

Naples. One would improvise a strain which others would

immediately sing in chorus to a charming melody. Each

in turn improvises thus, so that all have an opportunity of

exhibiting their talents for poetry and wit."8

In Newlands' description of canoeing in Sierra Leone,

he writes, "Boat-boys would stand on the bottom of the

boat and place one leg upon the seat. Then they lift

themselves upon the seat with both legs and while still

rowing, each would throw one foot backwards and upwards into the air, balancing on one foot and not relinquishing the oars. At same time they chanted a dirge-like ditty or sang some song, although evidently to them inspiring, had yet to me a melancholy strain of sadness.

. . . The boys beat the kettledrums vigorously and the

bugle rang out."9

The exclamation Eji (Aië) found at the close of

many African verses is typical of the shield struck by the

spear. The war song is stopped at a given signal, immediately the shields are elevated and a hissing ngu-ngu-ngu is heard through the crowd. From this comes

the word ngunquzela, meaning to stop a war song.

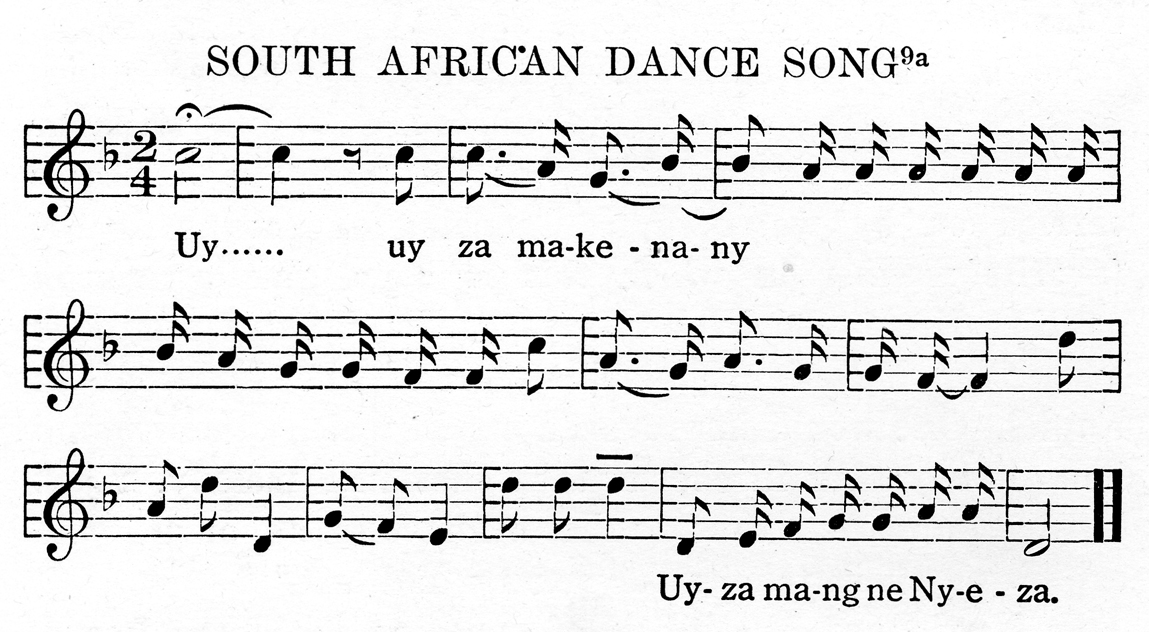

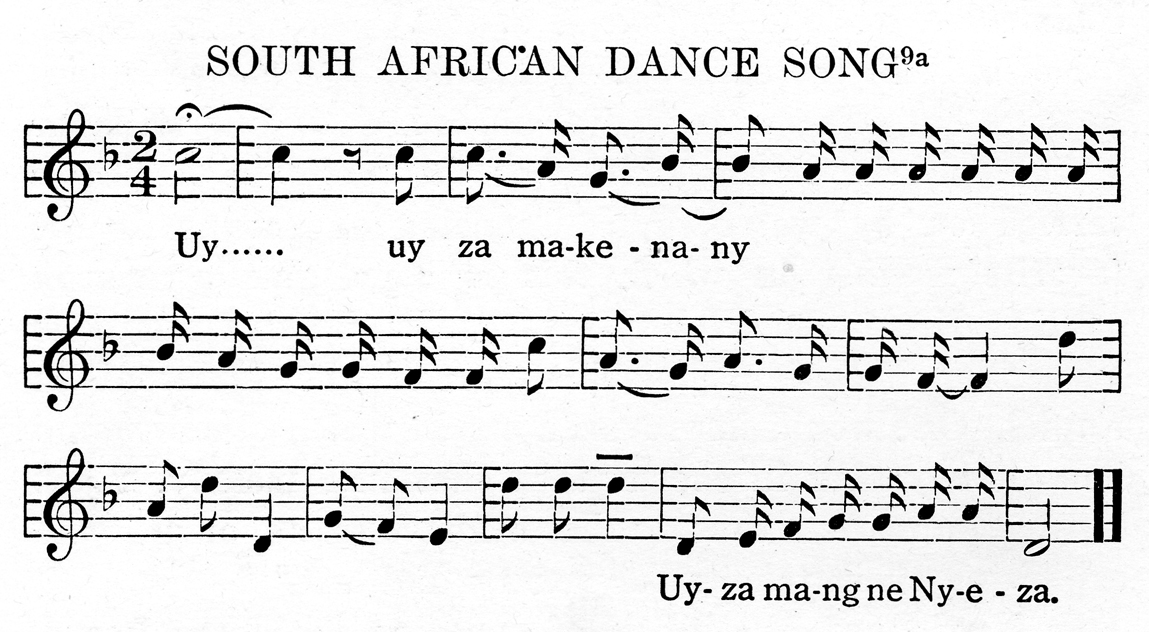

9a

9a

Then there are war dances.10 The Bantu of South Africa give war-dances (gila) at which time medicine is given

the soldiers to make them invulnerable. It follows the war-song. Usually there is but little change of position in the

dance, and the movements may consist of simply moving

the head and hands with a slow motion of the feet. Always the war-dances are accompanied by old chants, many

of which have been noted. One of them, which is the oldest of the Nkuna, dates back to 1820. It was sung before

the Zulu invasion before the arrival of Manukosi, in the

early XIX century. The dialect is Thonga.11 In the

gila a single dancer detaches himself from the circle of

warriors and stamps with all his strength on the ground.

He beats the earth with one long tread followed by three

short ones, all the time brandishing his weapons. His

place is taken by a younger man who leaps like an antelope. If the troops are detained in going to battle the

young men go dancing to the king to ask permission to

go forward.

Henry M. Stanley in Darkest Africa describes the Phalanx Dance which was given to celebrate a victory. In the

afternoon, one thousand warriors gathered and joined the

men, women and children whose voices arose in song high

above the drums. The main chorus was that of the

Wanyamwezi, called the best singers on the continent,

while the Bandussume under Katto, brother of Mazamboni, led the warriors to the Phalanx Dance.

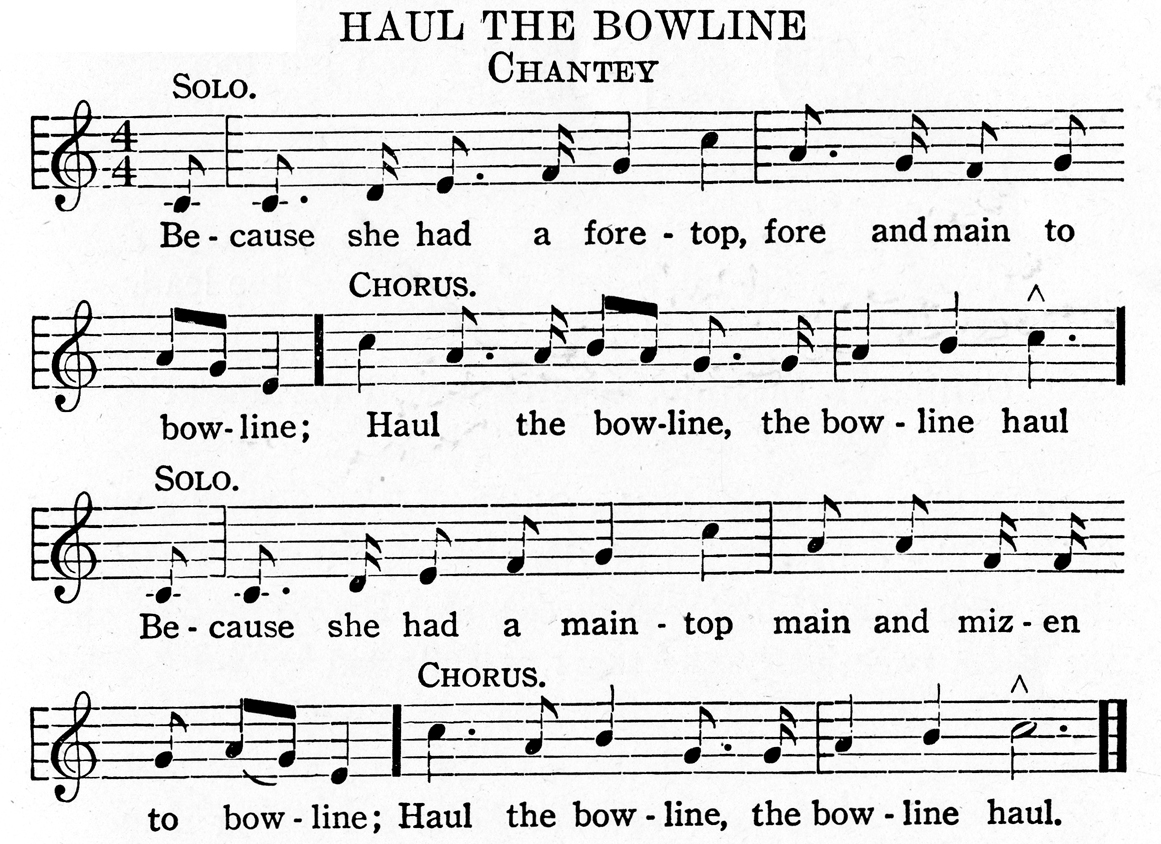

The African boat songs of yesterday may be the origin

of our sea-chanty of today. Even in far off Africa the

chanty had its use.12 All these songs help us to trace

history.

It is said that the scientific world was first told of the

wonders of the pre-Mohammedan era in Africa by the

French, who had carried on early excavations there. The

old Arabian explorer, El Bekri, who visited the Hausa

in 1050 A. D., told of the red mounds that are still seen

in the region of the lower Senegal, as having been ancient royal graves. But the list of the dead kings, then

of the second dynasty, is found through the medium of a

song which was chanted at the funeral festivals. The

singers, so the old "fairy-song of the Nupes" goes, called

each of the great chiefs by name, and told the number of

years and months of his reign.13

The old story as told in detail by Frobenius, fantastic

as it is, makes interesting reading. Of particular interest

to us, however, is the fact that important historical knowledge of the time before 1275 is given the world through

song. Describing the "god-like memory" of those who

lived before the time of the written word, the writer tells

of the gaffers who still recall the song which was sung

when workmen toiled in the building of pyramids, centuries old, and claims that every archaeologist can quote

extracts from the natives. While this is true, it is to

such scholars as Junod and Frobenius that we are indebted

for unparalleled accounts of the musical traditions of

the black continent.

Amidst the Tshi-speaking people of West Africa,14

dancing and singing in honor of the deceased take place

at funerals. Decima Moore and Major F. G. Guggisburg

in We Two in West Africa tell of funeral songs being

heard that were sung by a score of women who went up

and down the street dancing a weird measure. They

clapped hands in time to their song and circled around and

around a man singer, who sang short soli at intervals, the

chorus of the dirge being taken up by the women. The

song and dance were kept up for days by hired mourners.

Always there was the accompaniment of the drum.

George W. Ellis, formerly of Chicago, who was at the

town of Bomie when the Vai king died in 1904, stated

that, following a death, a large feast is spread and while

songs are given, drums announce the festivities of the day.

There are many mourning songs descriptive of the loss

of a family or tribe. Following the official period of

mourning for the dead chief, the African coronation is

held, an occasion of great moment. Among many tribes

it is a military affair in which the people declare their

loyalty to the new chief and he in turn to them. In parts

of South Africa the war dance known as the gila or giya,

is followed by the guba, which is a solemn chant used

interchangeably as a coronation chant, a war song, a

funeral dirge or patriotic hymn.

The classical war song of the Tembe and Maputju which

inspired Coleridge-Taylor's fine piano transcription "Lo-ko-ku-ti ga" (At the Break of Day), originated at the

coronation of Muwai who reigned at the close of the

eighteenth century. He was the great, great grandfather

of the chief Mabai who was deposed in 1896. Muwai,

whose son Makasana reigned from 1800 to 1850, is compared to the rising sun, and the words are thought to

recall a coronation at daybreak.15 Before going to war

and during coronation ceremonies the army sings this

old coronation song in praise of the royal family. Notice

is called to the change from minor to major and its return to the major mode.

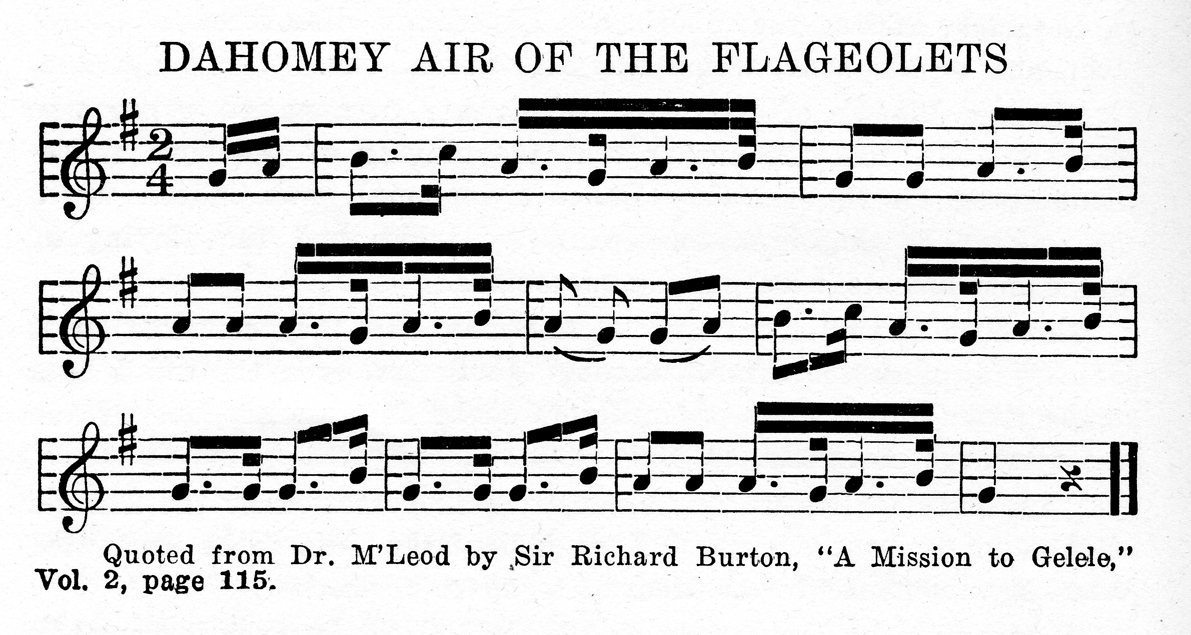

Sir Richard Burton gives many instances of dancing

and singing in connection with the "Grand Customs"

about the time of the New Year, 1864. He has many interesting things to say of this very old festival which was

founded upon a religious rite, and which included human

sacrifice and the slaying of captives. His work would

have been more valuable, however, had he not so often

descended to flippancy and ridicule. His lack of sympathy with the people of whom he wrote prevented him

from discovering the underlying significance of the

mystery dances and songs. He tells of sundry dances at

which Amazons (women soldiers) chant to a single cymbal, and then to a full band. This was followed by a

mock dance of "So," representative of the Thunder god,

which he considered buffonery without any mystical

meaning. At the king's "So-sin Custom" armed women

sang dirges in the minor key, clapped hands and presented

arms, after which followed a dance given by six Amazons.

These women excelled in the chanting of Nago songs.

It has been long thought that African folk-song has a

harmonic background. However, Ballanta, a native of

Sierra Leone who has been making musical researches in

West Africa under the auspices of the Guggenheim Foundation, wrote in the Journal of West Africa, of July 14,

1930, that "there is no perception of harmony as the

term is understood in music." He continues:

"What enters into a musical expression by way of tone

combination is a highly developed form of polyphony,

which may embrace two, or at most three parts. This

polyphonic form is the freest from the point of view of

concords and discords, and it is preponderantly rhythmic;

that is to say, each part preserves its individuality. There

appear to be no conditions as to the succession of intervals; and although there are evidences of the use of some

intervals rather than others, especially in the cadence,

one could not prove the rule.

"The perfect fourth is the basis of harmonic combinations; that is, where two parts sing together tone by tone.

Towards the cadence, however, other intervals may be

used as the major third and the major second; but the

major third is in all cases treated as discordant, whereas,

the major second is accepted as a concord.

"Taking the major diatonic scale as a standard, although that scale gives imperfectly the sounds produced,

the fourth and seventh of that scale are not fundamental

tones in the African perception, but subordinate tones.

The principal tone in African perception is that group of

tones answering to the second major diatonic scale; the

tones next in importance are the fifth and sixth being the

fourth below it. The other two tones are subordinate and

are used for cadential purposes, or otherwise, to divide

the interval of the perfect fourth. This appears to have

been the original perception."

Ballanta then concludes, "Each one of these standard

tones now has what may be called tones in opposite phases

with it. These other tones stand at the distance of about a

quarter tone above and below the standard tones and are

used for and instead of the standard tones; that is to say,

they rarely follow each other, so that the actual intonation of a quarter tone is rare."

Junod says of native South African harmony, that it

certainly exists, even if not always easy to detect. When

you hear a chorus of beautiful voices singing in two or

three parts, you at once perceive great differences between

their system of harmony and ours. These choruses are

by no means disagreeable, but are very strange to our

European ear. . . . I have succeeded in fixing the two

parts of the song of Zili which can be considered typical;

I owe it to two girls of Lourenco Marques, who had clear

voices and lent themselves willingly and with great patience to the long inquiry. One will notice a curious succession of fourths and sixths quite unusual in our music.

. . . The fourth seems to be more acceptable to the Bantu

ear than the third or the fifth."16

The author of this volume has heard a quartette of

Bechuanas sing native songs in harmony with half-tone

inflections, although the melodies were simple as were the

words, after those of a South African proverb. Guided

only by the ear, they improvised harmonic parts to the

leading voice.

We should note here also present-day characteristics.

Ballanta, who travelled about 7,000 miles in research work

in his native land and collected over 2,000 specimens of

African song, found that the African melodies did not

always consist of short melodic phrases of only two or

four bars endlessly repeated, but that there existed melodies of from twelve to sixteen measures without the appearance of one repetition. This he found true of the

Mende (Sierra Leone), Susu (French Guinea), and

Munsi (Northern Nigeria) tribes. The most interesting

melodies were those of the tribes of the middle region,

that had not been influenced by outside culture. Ballanta noted a most interesting example which was a flute

solo with vocal chorus which he heard sung by over sixty

voices at Makurdi, the town-seat of the Munsi tribe.17

In describing the dance songs he adds, "The highest class

is the artistic dance of the Yorubas. Cross rhythms in

abundance. In these dances one meets with characteristic

rhythms; that is to say, rhythms which have meanings

ascribed to them in directing the dancer how to proceed;

they act as cues, not necessarily with reference to a change

of dance steps, but with reference to action, either to retire, or to come forward, or go backward. They are the

beginnings of the drum-talking system."

In an essay read at the International Colonial Exhibition of Paris during the International Congress of Ethnography, by M. Félix Eboué, a Negro from French Guiana, graduate student of l'Ecole Coloniale and chief

colonial administrator, it was stated that among the

Oubanguians who do not know writing, the choruses are

sung only in middle range, as the children alone have

high voices. According to Eboué-Tell, who had collected

thirty-two songs, the minor modes predominate. The measures are in 4/4 or 2/4; the phrases short with ever-changing variations, the longest melodies never over eleven

measures while the shortest was that of five.

In the Banda songs from Baubi the language is so musical that they could be written "by means of musical notation as with syllables of our alphabet." The words are reproduced on the tom-tom lingua (drum) but they can also be spoken in tune with European musical instruments.18 Stephen Chauvet in La Musique Nègre, (1929) describes the beauty of the music given by characteristic

chanting of the porters and voyageurs, with the improvisations which are delicate and subtle, reminders of the song

of the troubadours of the Medieval epoch.

Today we find African song creeping from its native

heath and arousing curiosity and interest in the concert

hall. In London during the music season of 1932, a concert of Bantu songs and rhythms was given by the natives

named Montsieloa, Dube and Marimbela. The songs were

sung in Zulu, Sesuto, Lizosa, Matebele and other African

languages.

Mme. Grall, wife of the doctor-in-chief of the medical

Corps of Bambari, who is completing her studies of the

African song and speech, makes interesting observations

on the connection between African words and instruments.

As the D minor triad for a basis, she writes that "the

linda (drummer) speaks by striking the linga so as to reproduce exactly the rhythm of his own words and the

different tones of his dialect. Even the children understand the messages. . . . Whenever a message is about to

be transmitted, the 'broadcasting station' summons those

who can hear it by a series of strokes, in which it names

those to whom the message is to be given. The beginning

phrases may vary among stations, according to the 'mokhoundji linga' or drummer, but all of them mean, 'So and so, listen to me.'"

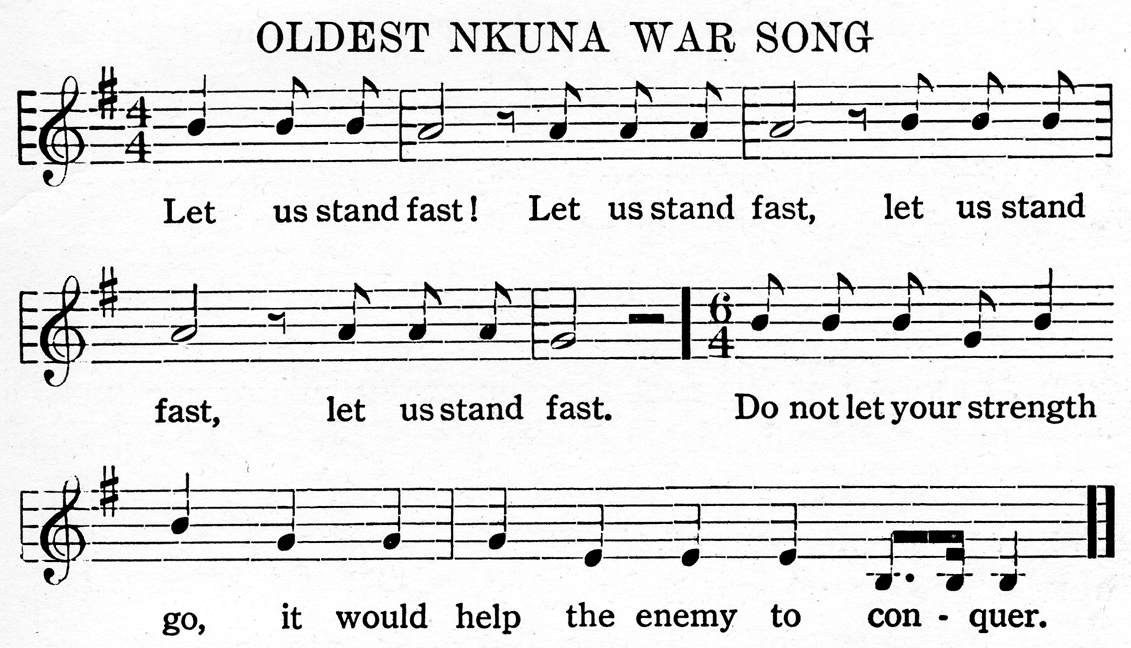

AFRICAN DRUMS

Certain words are always represented by the same

notes and rhythm, and thus Mme. Grall finds it is possible to distinguish a musical vocabulary of the Banda language. It is interesting to note that a South African native, Mark Radabe, conducting research in 1932, with

the idea of presenting an opera, the development of the

Bantu principles, would portray the Zulus in Basutoland.

During the year of 1932, R. C. Nathaniels, a West African

composer, gave recitals in Vienna for similar reasons.

Other performances have also invited attention to these

characteristics. In July, 1933, a group of African singers,

accompanied by dancers and the Royal Ashanti Drum

Corps under the direction of Duke Kwesi Kuntu, gave performances at the Century of Progress Exposition at

Chicago. Prior to their American visit, Dr. M. J. Herskovits, of Northwestern University, and other anthropologists

witnessed their entertainment abroad. According to the

American press, the fourteen "well-poised, beautifully

molded black men with drums four and one-half feet

high . . . gripped, stirred, and thrilled an audience of

people from all parts of the world, in most fantastic and

rhythmic ceremonial dances."

Kykunkor, "The Witch Woman," a native African

opera, the music by Asadata Dafora, a native of Sierra

Leone, West Africa, was the artistic sensation of the music

world when presented in New York during the season of

1934. The director, Asadata Dafora Horton, who came

to New York in 1929, is an African singer and dancer.

For some time unrecognized, he struggled to gain a hearing for Negro music that was more than the accepted

jazz. Receiving unstinted praise from John Martin, dance

critic of the New York Times, who heard an early presentation of Kykunkor in the Unity Theater Studio, the

musician was successful in having the dance opera performed in the Chanin Auditorium, New York, and elsewhere. An act from the opera was broadcast in June, 1934.

The libretto of this African opera is based on a folk

legend of love and marriage, and the setting is that of an

African village. Effective use is made of traditional chants

and dances. Leopold Stokowski, who with Lawrence and

other noted musicians have praised Kykunkor, is said to

have asked that he be taught the intricate African rhythms

as exhibited by the drummers. Abdul Assen in the role

of the witch doctor, showed remarkable dramatic ability.

The opera was given at the Newport Casino, Newport,

Rhode Island, during late August, 1934.

Although it is true that dance and song enlivened all

sections of Africa, we have long turned to Egypt for first

knowledge of music and musical instruments. According

to Dr. L. S. B. Leak, who has made a study of conditions

in East Africa (1932), recent excavations there give evidence that the history of man goes back to an age greater

than in any other section of the world.19 It is not surprising that many Negro-African instruments show a kinship to many of those found in Egypt, since centuries of

commerce and conquest brought into close contact many

races of men — Arabian and Moorish, Assyrian and Persian,

Ethiopian and Egyptian. Egypt learned much from

the purely Negro Africa, and the latter from the former.

It is said that stringed instruments owe their origin to

Negro Africa.

The African tom-tom, the drum, although not always

used as a musical instrument, is of unusual importance.

It is claimed that in a hot climate, the older the drum gets

the tauter the string becomes. The method of tuning is

by placing the instrument over a fire to contract the skin

or in water to expand it. The drum has three distinct

and separate usages — by the priests in worship, by the

youth in affairs of love, and by chiefs and rulers in military life. However, there is no custom or ceremony connected with daily life but that the drum has a share

therein. No march is undertaken without the call of the

drum, and it is also used as the hunters prepare for the

leopard hunt. In the Tshi-speaking country, the announcement of all festivals is made by beating of the

large state drum at sunset after which signal, songs and

discharge of fire-arms break out from all quarters of the

town. The harvest festival in September, lasting a fortnight, is commenced by the beating of the drums. Among

the Kafirs, there are drum-calls for all occasions. Besides the

all-night drumming to scare away wild animals, there is

the summons at day break which is known as the reveille.

Much importance is laid upon the morning summons.

The African tom-tom has had parallels abroad. Daniel

Alomia Robles, a Peruvian musician and archaeologist,

has a flute which was found in one of the old tombs in

Peru. Among the old Inca instruments, some of which are

over 3,000 years old, is a 5 string harp. Of the 4 note

instruments, the scale was found to be Re, Fa, Sol, La,

later enlarged by the interval of a third, which is a complete Inca pentatonic scale. Mr. Robles claims this is in

advance of the Greeks. As we know, this Inca music,

later absorbed by the Spanish, was again modified by

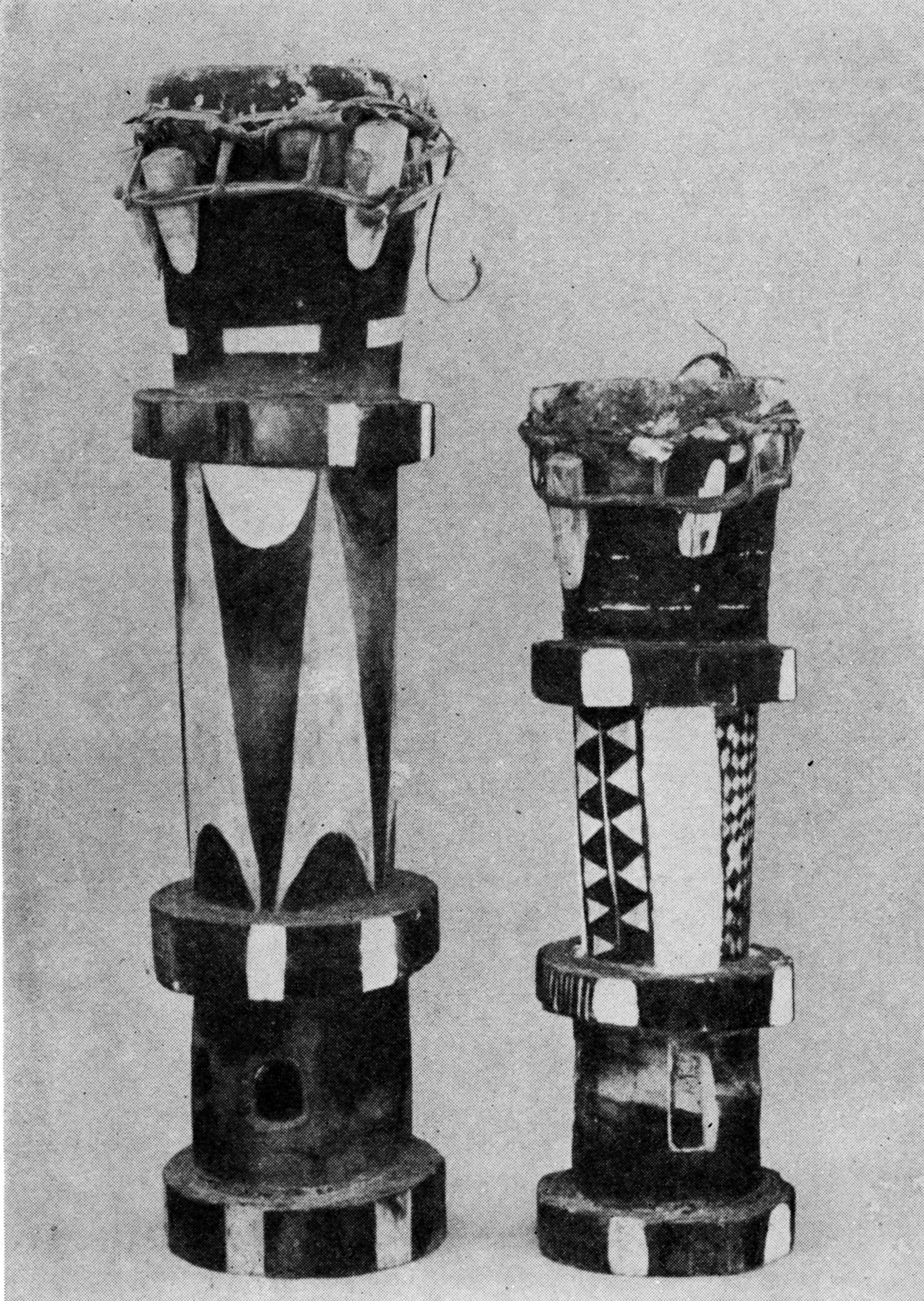

African influences. In this the "marimba", or xylophone,

a native African piano, was an important factor.

MARIMBA OR XYLOPHONE

In Puerto Rico, as in the Virgin Islands, the guiro or

juiro (pronounced "weero"), is the most popular instrument. It is seen everywhere and is the main instrument of percussion used in that section of orchestras and

bands. Here the juiro is made of hollowed gourds, cut

with, many small grooves and decorated with simple motives and two or three cut-outs. The one in the possession

of the author is made to resemble a fish. The juiros, made

of various sizes, are stroked with a steel wire or hair-pin.

The author has listened with amazement to the extraordinary playing of a Negro juiro performer in the Puerto

Rican Municipal Band under the conductor, Tizal, in San

Juan. The many and varied rhythmic effects and the

rapidity with which he produces syncopated notes, makes

him the center of attraction to tourists who listen to the

outdoor concerts given in the plaza.

[CHAPTER III]

Notes, Chapter II

[Page 16]

1

René Bassett, noted folklorist, says that certain episodes mentioned in South African stories are to be found in the folklore

of the ancient Greek and Roman, the modern French and Italian,

and in the Scotch and German as well. He gives an explanation

of the phenomenon in which he declares that there may be such a

similarity in the minds of the various races when still in their

primitive phase of development, that they have invented the stories

independently — or that they belong to primitive humanity and all

the races have taken tales with them in their migrations and in

contact between the various races, the tales have spread all over

the world. — Revue des Traditions Populaires, "Les Chants et les Contes des Ba Ronga," June, 1918.

[Page 17]

2

The tales of Africa are very old. A Sudanese proverb reads:

"Salt comes from the North, gold comes from the South, but the

word of God and wisdom and beautiful tales, they are found only

in Timbuctoo." Not only in Jenne, the ancient city which played

so important a part in the Sudan centuries ago, but throughout

Timbuctoo an entire class of the population was devoted to the

study of letters, and here not only talebearers of the old legends

are found, but a collection of ancient manuscripts as well. Among

the histories found here was one written by Abderrahman Es-Sadi

who recorded events before 1656. Of the libraries owned by educated natives, Ahmed Baba declared, "Of all my friends I had

the fewest books, and yet when your soldiers despoiled me they

took 1,600 volumes."

In the old manuscripts the old writers who also copied books,

as material was scarce, were called sheiks — termed "marabuts" by

the Sudanese of today. When the marabuts were asked why they

did not write more books instead of making records, the explanation

closed with this illuminating statement which arouses the sympathy

of musicians as well as writers, "Sometimes we are asked to

write talismans and to copy books, but that does not give us

sufficient to live upon. Many are obliged to devote themselves to

commerce and absorbed by the care of not dying of hunger, how

can they find time to write?" Du Bois, Felix, Timbuctoo, the Mysterious, chap. XIV, p. 319.

The author was told by a learned African, the late Professor

Aggrey, that among the Fantis the people resort to the telling of

facts and the description of events on wood, not because of ignorance, but because of the prevalence of destructive white ants which

causes the people not to attempt the saving of papers.

[Page 18]

3

Schweinfurth, H., The Heart of Africa, vol. II, p. 30-31.

[Page 19]

4

Frobenius, Leo, The Voice of Africa. Vol. II, pp. 526-8. Nile

here may be confused with some other stream.

[Page 20]

5

Junod, Henri A., The Life of a South African Tribe, vol. II,

pp. 177-8.

6

Ibid., vol. I, pp. 373-5 and vol. II, p. 259.

[Page 21]

7

Ellis, A. B, Tshi-Speaking People of the Gold Coast of West Africa, p. 229.

8

Wallaschek, Vier Jahre in Africa, I, 221.

9

Newland, H. O., Canoeing on the Rokelle, p. 83.

[Page 22]

9a

Noted by M. C. Hare from S. Plaatje of South Africa.

10 Junod, Henri, The Life of a South African Tribe, VoL II, pp. 436-8.

11 Junod, Henri, The Life of a South African Tribe, Vol. II, pp. 436-8.

[Page 23-24]

12

L'abbé Bouche gives a song by his canoe men when he travelled on the lagoon near Porto Novo.

"You are great, you are strong, Oh Jaledeh! If you choose you

would rival Shango (the lightning rod) in power. But to be terrible

and cruel seems to you unworthy of a god, and you prefer to make

yourself renowned by the benefits of your protection. We trust in

you, oh Jaledeh — be propitious to us." (Chorus repeats) "Jaledeh,

good deity, guide us, shield us from harm."

[Page 24]

13

Leo Frobenius, The Voice of Africa, vol. II, p. 368.

14

Ellis, George W., Negro Culture in West Africa, p. 24.

[Page 25]

15

Twenty-four Negro Melodies, Transcribed for Piano, by S.

Coleridge-Taylor, Oliver Ditson Co.

[Page 28]

16

Junod, Henri A., Life of a South African Tribe, vol. II, p. 268.

17 "Gathering Folk-tunes in the African Country," Mus. Amer.,

Sept. 25, 1926.

[Page 29]

18

Revue du Monde Noir, April, 1932. Eboué, Félix, The Banda, Their Music and Language.

[Page 31]

19 See Appendix.

CHAPTER III

AFRICAN INFLUENCES IN AMERICA

NEGRO

SONG AND

AFRICAN

SYSTEMS —

COMPARISONS —

SONG IN 1835 —

NEGRO

MINSTRELSY —

NEGRO

MINSTREL

TROUPES —

"JIM

CROW"

SONG, 1815 —

STEPHEN

FOSTER, 1845 —

POPULAR

BALLADS —

SONG

WRITERS —

PLANTATION

SONGS, 1862 —

FISK