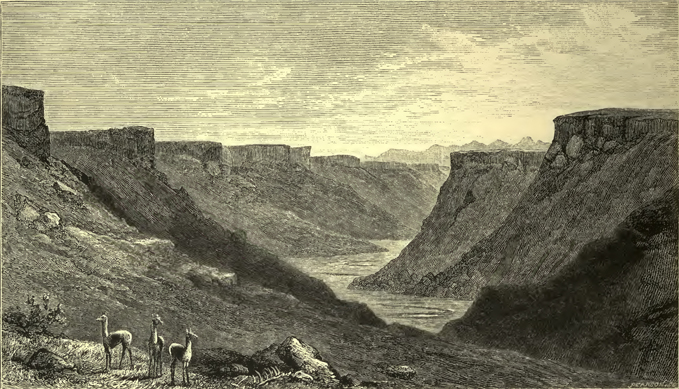

A GUANACO ON THE LOOK-OUT.

CHAPTER I.

WHY PATAGONIA? – GOOD-BYE – THE START – DIRTY WEATHER – LISBON – THE ISLAND OF PALMA – PERNAMBUCO.

"PATAGONIA! who would ever think of going to such a place?" "Why, you will be eaten up by cannibals!" "What on earth makes you choose such an outlandish part of the world to go to?" "What can be the attraction?" "Why, it is thousands of miles away, and no one has ever been there before, except Captain Musters, and one or two other adventurous madmen!"

These, and similar questions and exclamations I heard from the lips of my friends and acquaintances, when I told them of my intended trip to Patagonia, the land of the Giants, the land of the fabled Golden City of Manoa. What was the attraction in going to an outlandish place so many miles away? The answer to the question was contained in its own words. Precisely because it was an outlandish place and so far away, I chose it. Palled for the moment with civilisation and its surroundings, I wanted to escape somewhere, where I might be as far removed from them as possible. Many of my readers have doubtless felt the dissatisfaction with oneself, and everybody else, that comes over one at times in the midst of the pleasures of life; when one wearies of the shallow artificiality of modern existence; when what was once excitement has become so no longer, and a longing grows up within one to taste a more vigorous emotion than that afforded by the monotonous round of society's so-called "pleasures."

Well, it was in this state of mind that I cast round for some country which should possess the qualities necessary to satisfy my requirements, and finally I decided upon Patagonia as the most suitable. Without doubt there are wild countries more favoured by Nature in many ways. But nowhere else are you so completely alone. Nowhere else is there an area of 100,000 square miles which you may gallop over, and where, whilst enjoying a healthy, bracing climate, you are safe from the persecutions of fevers, friends, savage tribes, obnoxious animals, telegrams, letters, and every other nuisance you are elsewhere liable to be exposed to. To these attractions was added the thought, always alluring to an active mind, that there too I should be able to penetrate into vast wilds, virgin as yet to the foot of man. Scenes of infinite beauty and grandeur might be lying hidden in the silent solitude of the mountains which bound the barren plains of the Pampas, into whose mysterious recesses no one as yet had ever ventured. And I was to be the first to behold them! – an egotistical pleasure, it is true; but the idea had a great charm for me, as it has had for many others. Thus, under the combined influence of the above considerations, it was decided that Patagonia was to be the chosen field of my new experiences.

My party consisted of Lord Queensberry and Lord James Douglas, my two brothers, my husband, and myself, and a friend, Mr. J. Beerbohm, whose book, Wanderings in Patagonia, had just been published when we left England. We only took one servant with us, knowing that English servants inevitably prove a nuisance and hindrance in expeditions of the kind, when a great deal of "roughing it" has to be gone through, as they have an unpleasant knack of falling ill at inopportune moments.

Our outfit was soon completed, and shipped, together with our other luggage, on board the good ship "Britannia," which sailed from Liverpool on the 11th December 1878. We ourselves were going overland to join her at Bordeaux, as we thereby had a day longer in England. Then came an unpleasant duty, taking leave of our friends. I hate saying good-bye. On the eve of a long journey one cannot help thinking of the uncertainty of everything in this world. The voice that bids you God-speed may, before you return, perhaps be silent for ever. The face of each friend who grasps your hand vividly recalls some scene of pleasant memory. Now it reminds you of some hot August day among the purple hills of Scotland, when a good bag, before an excellent lunch, had been followed by some more than usually exciting sport. The Highlands had never looked so beautiful, so merry a party had never clambered down the moors homeward, so successful a day had never been followed by so jolly an evening; and then, with a sigh, as your friend leaves you, you ask yourself, "Shall I ever climb the moors again?" Now it is to Leicestershire that your memory reverts. The merry blast of the huntsman's horn resounds, the view-halloa rings out cheerily on the bright crisp air of a fine hunting morning; the fox is "gone away," you have got a good start, and your friend has too. "Come on," he shouts, "let us see this run together!" Side by side you fly the first fence, take your horse in hand, and settle down to ride over the broad grass country. How distinctly you remember that run, how easily you recall each fence you flew together, each timber-rail you topped, and that untempting bottom you both got so luckily and safely over, and above all, the old farm-yard, where the gallant fox yielded up his life. Meanwhile, with a forced smile and a common-place remark, you part; and together, perhaps, you may never hear the huntsman's horn, never charge the ox-fence, never strive to be foremost in the chase again!

With these thoughts passing through my mind I began to wonder why I wanted to leave England. I remembered for the moment only the pleasant features of the past, and remembering them, forgot the feelings and circumstances which had prompted me to embark on my present enterprise. The stern sex will possibly reprehend this exhibition of female fickleness of purpose. May I urge in its palliation that my weakness scarcely lasted longer than it has taken me to write this?

14th December. – On a cold, rainy afternoon we steamed down from Bordeaux in a little tender to join the "Britannia," which was anchored off Pauillac. We were soon alongside, and were welcomed on board by Captain Brough, under whose guidance we inspected, with a good deal of interest, the fine ship which was to be our home for some time. It would be superfluous for me to describe the excellent internal arrangements on board; few of my readers, I imagine, but are acquainted, either from experience or description, with the sumptuous and comfortable fittings-up of an Ocean passenger-steamer.

Soon the anchor was up – the propeller was in motion, and our nerves had hardly recovered from the shock inflicted by the report of the gun which fired the parting salute, ere Pauillac was scarcely distinguishable in the mist and rain astern. By the time dinner was over we were altogether out of sight of land, the rain was still falling heavily, and prognostications of dirty weather were being indulged in by the sailors. Giving a last look at the night, I turned into the captain's cosy deck-house, where I found my companions deep in the intricacies and wranglings of a rubber at whist, in which I, too, presently took a hand. As time went on, indications that it was getting rather rough were not wanting, in the swaying of the ship and the noise of the wind; but so comfortable were we in our little cabin, with the curtains drawn and lamps lit, that we were quite astonished when the captain paid us a visit at about nine o'clock, and told us that it was blowing a regular gale.

The words were hardly out of his mouth when the ship heeled suddenly over under a tremendous shock, which was followed by a mighty rush of water along the decks. We ran out, thinking we must have struck a rock. The night was as black as pitch, and the roaring of the wind, the shouts of the sailors, and the wash of the water along the decks, heightened with their deafening noise, the anxiety of the moment. Fortunately the shock we had experienced had no worse cause than an enormous sea, which had struck the ship forward, and swept right aft, smashing whatever opposed its destructive course, and bending thick iron stanchions as if they had been mere wires.

As soon as the hubbub attendant on this incident had somewhat subsided, thankful that it had been no worse, we returned to our game at whist, which occupied us till eleven o'clock, at which hour, "all lights out" being the order of the ship, we turned into our cabins to sleep the first night of many on board the "Britannia."

The next day was fine and sunny, and so the weather continued till we reached Lisbon, three days after leaving Bordeaux, when it grew rather rough again. At Lisbon we remained a day, taking in coal and fresh provisions – and then once more weighed anchor, not to drop it again till the shores of the New World should have been reached.

Just as it was beginning to dawn on the morning of the second day after leaving Lisbon, I was awakened by the speed of the vessel being reduced to half its usual ratio, for so accustomed does one become in a short time to the vibration of the screw, that any change from its ordinary force immediately disturbs one's sleep. Looking out of my cabin-window I could see that we were close to land, so, dressing hurriedly, I went on deck. We seemed to be but a stone's-throw from an island, whose bold rugged heights rose up darkly against the pale light that shone in the morning sky. At one point of the shore the revolving light of a beacon flashed redly at intervals, growing fainter and fainter each time, as day slowly broke, and a golden haze began to flood the eastern horizon. In the darkness the island looked like a huge bare rock, but daylight showed it clothed in tolerably luxuriant vegetation. The presence of man was indicated by the little white houses, which could be distinguished nestling in crannies of its apparently steep green slopes. This was the island of Palma, one of the Canary group, and small though it looked, it numbers a good many inhabitants, and furnishes a fair contingent of emigrants to the River Plate, where "Canarios," as they are called, are favourably looked upon, being a skilful, industrious race.

The days slipped quickly by, and soon, as we neared the equator, it began to grow intensely hot. Christmas Day spent in the tropics did not rightly appear as such, though we kept it in the orthodox manner, the head-steward preparing quite a banquet, at which much merriment reigned, and many speeches were spoken.

We arrived at Pernambuco on the 28th December, but did not go on shore, as we were only stopping in the port a couple of hours, and were told, moreover, that there is nothing to be seen when one is there. We amused ourselves watching the arrival of some fresh Brazilian passengers, who were going with us to Rio. The extensiveness of their get-up might have vied with that of Solomon "in all his glory" – but tall hats, white trousers, and frock-coats seemed ludicrously out of place on board ship. Not less funny was the effusiveness of their affectionate leave-takings. At parting they clasped their friends to their breasts, interchanging kisses in the most pathetic manner, and evincing an absence of mauvaise honte in the presence of us bystanders, which was at once edifying and refreshing. Autres pays, autres mœurs.

Some boatmen came alongside, bringing baskets of the celebrated Pernambuco white pineapples. We bought some of this fruit, which we thought delicious: it is the only tropical fruit which, in my opinion, can vie with European kinds. "Luscious tropical fruit" sounds very well, as does "the flashing Southern Cross;" but nearer acquaintance with both proves very disappointing, and dispels any of the illusions one may have acquired respecting them, from the over-enthusiastic descriptions of imaginative travellers. Very soon the captain came off shore again, with the mails, etc. A bell was rung, the fruit-vendors were bundled over the side of the ship, chattering and vociferating, – last kisses were interchanged by the Brazilian passengers and their friends, up went the anchor, round went the screw, bang! went our parting salute, and, thank God, we are off again, with a slight breeze stealing coolingly over us, doubly grateful after the stifling heat which oppressed us while at anchor.

CHAPTER II.

BAHIA – RIO DE JANEIRO – RIO HARBOUR – THE TOWN – AN UPSET – TIJUCA – A TROPICAL NIGHT – MORE UPSETS – SAFETY AT LAST.

A DAY after leaving Pernambuco we dropped anchor again; this time in the magnificent "Bahia de todos los Santos," the ample dimensions of which make its name a not inapposite one. Bahia itself is built on a high ridge of land, which runs out into the sea, and forms a point at the entrance of the harbour. The town is half hidden among huge banana trees and cocoanut palms, and seen from on board looks picturesque enough. After breakfast our party went on shore, accompanied by the captain, and for an hour or so we walked about the streets and markets of the lower town, which stands at the base of the ridge above mentioned. We found it as dirty and ugly as could well be, and our sense of smell had no little violence done to it by the disagreeable odours which pervaded the air. There was a great deal of movement going on everywhere, and the streets swarmed with black slaves, male and female, carrying heavy loads of salt meat, sacks of rice, and other merchandise to and from the warehouses which lined the quays. They all seemed to be very happy, to judge by their incessant chatter and laughter, and not overworked either, I should think, for they were most of them plump enough, the women especially being many of them almost inconveniently fat. Finding little to detain us in the lower town, we had ourselves transported to the upper in an hydraulic lift, which makes journeys up and down every five minutes.

Then we got into a mule-tramway, which bowled us along the narrow streets at a famous pace. Soon getting clear of the dirty town, we drove along a pleasant high-road, on either side of which stood pretty little villas, shaded by palms and banana-trees, and encircled by trim well-kept gardens, bright with a profusion of tropical flowers. Now and then we could catch a glimpse of the sea too, and as we went along we found the tram was taking us out to the extreme point of the ridge mentioned above. Before we reached it we had to change our conveyance once or twice, as occasionally we came to a descent so steep that carriages worked up and down by hydraulic machinery had been established to ply in conjunction with the ordinary mule-trams. At last we were set down close to the seashore, near a lighthouse which stands in a commanding position on the point. The view which was now before us was a splendid one; the immense bay lay at our feet, and beyond spread the ocean, dotted with the tiny white sails of numberless catamarans, as the queer native fishing-boats are called, which looked like white gulls resting on its blue waters. But the heat in the open was so overpowering that we soon had to take refuge in a little café close by, where we had some luncheon, after which we went back to Bahia the way we had come, by no means sorry to get on board the cool, clean ship again. Half an hour after our arrival the anchor was weighed, and we steamed off, en route for Rio de Janeiro.

New Year's Day, like Christmas Day, was passed at sea, and we celebrated it with much festivity. Altogether our life on board was a most agreeable one, thanks to the kindness and attentions of the captain and his officers, and the days flew by with surprising rapidity. Four days after leaving Bahia we sighted land off Rio, at an early hour of the morning. Anxious to lose nothing of the scenery, I had risen at about four o'clock, and certainly I had no reason to repent of my eagerness. We had passed Cape Frio, and were steaming along a line of coast which runs from the cape up to the opening of the bay. Thick mists hung over the high peaks and hills, shrouding their outlines, and along the shore the surf broke with a sullen roar against the base of the cliffs which fell abruptly down to the sea. As yet all was grey and indistinct. But presently the sun, which for a long time had been struggling with the mists, shone victoriously forth; the fog disappeared as if by magic, disclosing, bathed in the glow of sunrise, a grand scene of palm-covered cliffs and mountains, which rose, range beyond range, as far as the eye could reach. In front of us lay Rio Harbour, with the huge Paõ de Agucar, or Sugar Loaf Mountain, standing like a gigantic sentry at its entrance. In shape it is exactly like the article of grocery from which it takes its name, and rises abruptly, a solid mass of smooth rock, to a height of 1270 feet. Its summit, long considered inaccessible, was reached by some English middies a few years ago. Much to the anger and disgust of the inhabitants of Rio, these adventurous youngsters planted the Union Jack on the highest point of the Loaf, and there it floated, no one daring to go up to take it down, till a patriotic breeze swept it away. Directly opposite is the Fort Santa Cruz, which, with its 120 guns, forms the principal defence of the harbour. Soon we were gliding past it, and threading our way through the numerous craft which studded the bay, we presently dropped anchor in front of Rio, and found ourselves at leisure to examine the harbour, one of the finest and largest in the world. Covering a space of sixteen miles in a north and south direction, it gradually widens from about three-quarters of a mile at its entrance to fifteen miles at its head. The town stands on the western side of the bay, at about two miles from its entrance. It is backed by a high range of mountains, and, as seen from the bay, nestling amidst oceans of green, presents a most pleasing appearance. The harbour is dotted with little islands, and all along its shores are scattered villages, country seats, and plantations.

As soon as the captain had got through his duties we took our places in his boat, and started off for the shore. On landing at a slippery, dirty, stone causeway, we were surrounded by a crowd of negroes, who jabbered and grinned and gesticulated like so many monkeys. Making our way through their midst, we passed by the market-place, and then, threading a number of hot, dirty, little streets, we at last got into the main street of the town, which was rather broad, and shaded on either side by a row of trees.

The public buildings at Rio are all distinguished by their peculiar ugliness. They are mostly painted yellow, a hue which seems to prevail everywhere here, possibly in order to harmonise with the complexion of the inhabitants. The cathedral forms no exception to the general rule. We entered it for a moment, thinking that we might possibly see some good pictures from the time of the Portuguese dominion. But we found everything covered up in brown holland. Nossa Senhora da Francisca, or whatever virgin saint the church is dedicated to, was evidently in curl-papers, and we could see nothing, though we could smell a great deal more than was agreeable. Truly I did not envy the saints their odour of sanctity. To my mundane nostrils this same odour smacked strongly of garlic and other abominations. We soon got tired of wandering aimlessly about, and feeling little desire to stop in the town any longer, we hired a carriage and started off for a little place called Tijuca, which lies high up among the hills behind Rio.

Our coach was drawn by four fine mules, who galloped along the streets at a rattling and – inasmuch as the driver was evidently an unskilful one – an undesirable pace. We remonstrated with him, but were told that it was the custom of the country to drive at that rate. So, in deference to the "custom of the country," on we went at full gallop, shaving lamp-posts, twisting round sharp corners, frightening foot-passengers, and narrowly missing upsetting, or being upset by, other vehicles which came in the way.

I was quite thankful when we at last got safely clear of the town. The road lay amongst the most beautiful scenery, and the heat, though considerable, was not oppressive enough to interfere with my enjoyment of it. After a couple of hours' driving we halted to give the mules a rest near a little brook, which came rippling out from the shady mass of vegetation which lined the road. I sat down under a banana tree, letting my eyes wander in lazy admiration over the scene at our feet. We had gradually got to a good height above Rio, and through a frame of leaves and flowers I could see the town, the blue bay studded with tiny green islands, and beyond, the rugged mountains, with a light mist hanging like a silver veil over their purple slopes.

When the mules were sufficiently rested we got into the carriage, and starting at a brisk trot, it was not long before we got to the summit of a hill, at the foot of which, in a little valley, lies Tijuca. Before reaching it a rather stiff incline had to be descended, and one of the wheelers, either blown or obstinate, refused to hold the carriage back. The driver insisted that the animal was only showing temper, and commenced to flog it. Foreseeing the result, we all got out of the carriage, and left the man to his own devices. He persisted in whipping the recalcitrant mule, and, as might have been expected, he presently started the other animals off at full gallop, leaving their comrade the option of following suit or falling. It chose the latter course, and after a good deal of slipping and sliding, went down with a tremendous crash. The other three, taking fright, immediately bolted, and we soon lost sight of carriage and driver in a cloud of dust. We followed on down the hill as fast as we could, rather anxious for the safety of the driver. Here and there, as we hurried along, we came across a piece of broken harness, and presently, on turning a sharp corner, we suddenly came upon the overturned carriage, the mules struggling and kicking in a confused heap, and the driver, unhurt but frightened, sitting in the grass by the side of the road. Assistance having been procured from Tijuca, which was close at hand, the mules were freed, and the carriage raised off the dragged mule, which we expected to find killed. To our surprise, however, no sooner were its limbs at liberty than it sprang up and began to crop the grass in utter unconcern as to the numerous wounds all over its body. A horse in such a state would have been completely cowed, and would probably never have been of any use again.

Leaving the driver to make the best of his position, we walked down to the Hotel Whyte, which lies snugly ensconced among palms and orange-groves at Tijuca. The building, with its clean cool rooms, shaded by verandahs, looked particularly inviting after the establishments we had been in at Rio, and it was pleasant too, to be waited on by Englishmen – the proprietor and his staff being of that nationality. A little stream runs past the hotel, feeding a basin which has been hewn out of the rock, where visitors can refresh themselves with a plunge, a privilege of which the gentlemen of our party were not slow to profit.

After I had rested a little I strolled away among the woods, feasting my eyes on the beauty and novelty of the vegetation, and on the delightful glimpses of scenery I occasionally stumbled across, to attempt to describe which would only be doing them an injustice. But that even this paradise had its drawbacks I was not long in discovering. I was about to throw myself on a soft green bank, fringed with gold and silver ferns and scarlet begonias, that stretched along a sparkling rivulet, when suddenly my little terrier darted at something that was lying on the bank, and pursued it for a second, till my call brought her back. The "something" was a snake of the Cross, whose bite is almost instantaneously fatal, and as I quickly retraced my steps to safer ground I thanked my stars that I had been spared a closer acquaintance with this deadly reptile. When I got back I had a swim in the rocky basin above mentioned, which refreshed me wonderfully. Soon afterwards we sat down to dinner, winding up the day by a cheery musical evening.

Before going to bed, enticed by the beauty of the night, I strolled for an hour or more among the woods at the back of the hotel, and gradually, attracted by the noise of falling waters, I made my way to a little cataract, which, coming from some rocky heights above, dashed foaming into a broad basin, and swirling and bubbling over a stony bed, disappeared below in the shadows of a lonely glen. The moon, which was now shining brightly, cast a pale gleam over its waters, and myriads of fireflies flashed around like showers of sparks. Not a sound was heard save the roar of the water, and hardly a breath of wind stirred the giant foliage of the sleeping forests. For a long time I sat giving myself up to the softening influences of my surroundings, and thinking, amidst the splendour of that warm tropical night, of the dear old country far away, now, no doubt, covered with ice and snow.

As we had to be on board the steamer by twelve o'clock the next morning, the carriages were ordered for eight o'clock, by which time we were up and had breakfasted. The captain, my husband, brother, and myself, took our seats in a carriage drawn by two mules, Queensberry and Mr. B. following in a Victoria. Having said good-bye to Mr. Whyte, we told our driver to start, cautioning him, as he was the same Jehu who had driven us so recklessly the day before, to be more careful. But again, for some unaccountable reason, he cracked his whip and started off at full gallop. Again the mules bolted, and like lightning we went down a little incline which leads from the hotel to the road. Then a sharp turn had to be made, seeing which we held on like grim death to the carriage, an upset being now palpably inevitable. On we went – the carriage heeled over, balanced itself for a moment on its two left wheels, and then, catching the corner of a stone bridge, over it went with a crash, burying us four luckless occupants beneath it, and hurling the driver into the brook below. Happily the shock had thrown the mules as well, for had they galloped on, huddled as we were pell-mell among the wheels of the carriage, the accident must have ended in some disaster. As it was, we had a most miraculous escape. The driver, who meanwhile had picked himself, drenched and crestfallen, out of the brook, came in for a shower of imprecations, which his stupidity and recklessness had well earned for him. He made some feeble attempts at an explanation, but no one understood him, and he only aggravated the virulence of our righteous wrath.

However, something had to be done, and quickly, if we were to reach the steamer by twelve o'clock. The Victoria was now the only conveyance left, and we could not all get into it. As luck would have it, whilst we were debating, a diligence was seen coming along the road, and, as it proved, there were sufficient vacant seats to accommodate all our party, – Queensberry, Mr. B. and myself going in the Victoria. The driver having assured us that the mules were perfectly quiet, and he himself appearing a steadier sort of man than the other unfortunate creature, we felt more at ease, and certainly at first start all went smoothly enough. But, strange to say, we were doomed to incur a third upset. When we came to a steep descent, instead of driving slowly, our coachman, for some inexplicable reason, actually urged his animals into a gallop. We called to him to stop, but that was already beyond his power, the mules having again bolted, and, to make matters still more desperate, one of the reins broke, leaving us completely at the mercy of accidents. The road wound down the side of a steep hill, and each time the swaying carriage swung round one of the sharp curves we were in imminent danger of being dashed over the roadside, down a precipice three hundred feet in depth. The peril of this eventuality increased with our momentum, and, as the lesser of two evils, we had to choose jumping out of the carriage. This we did at a convenient spot, and fortunately, though we were all severely cut and bruised, no bones were broken. In another second the coach and driver would have disappeared over the precipice had not one of the mules suddenly fallen, and, acting as a drag on the coach, enabled the driver to check the other mule just in the nick of time.

To meet with three accidents in twenty-four hours was rather too much of a good thing, and vowing that we had had enough of Brazilian coachmanship to last us all our lives, we completed the rest of the way on foot, arriving two hours after the appointed time, on board the old "Britannia." We presented a very strange appearance, our clothes torn and dust-stained, and our faces covered with cuts and bruises; but a bath and a little court-plaster soon put us all right, and we were on deck again in time to have a last look at Rio as we steamed away.

CHAPTER III.

BEAUTIES OF RIO – MONTE VIDEO – STRAITS OF MAGELLAN – TIERRA DEL FUEGO – ARRIVAL AT SANDY POINT – PREPARATIONS FOR THE START – OUR OUTFIT – OUR GUIDES.

I COULD not repress a pang of regret as we steamed slowly out of Rio Harbour. There may be scenes more impressively sublime; there are, without doubt, landscapes fashioned on a more gigantic scale; by the side of the Himalayas or the Alps, the mountains around Rio are insignificant enough, and one need not go out of England in search for charming and romantic scenery. But nowhere have the rugged and the tender, the wild and the soft, been blended into such exquisite union as at Rio, and it is this quality of unrivalled contrasts, that, to my mind, gives to that scenery its charm of unsurpassed loveliness. Nowhere else is there such audacity, such fierceness even of outline, coupled with such multiform splendour of colour, such fairy-like delicacy of detail. As a precious jewel is encrusted by the coarse rock, the smiling bay lies encircled by frowning mountains of colossal proportions and the most capricious shapes. In the production of this work the most opposite powers of nature have been laid under contribution. The awful work of the volcano; the immense boulders of rock which lie piled up to the clouds in irregular masses, have been clothed in a brilliant web of tropical vegetation, spun from sunshine and mist. Here nature revels in manifold creation, life multiplies itself a million fold, the soil bursts with exuberance of fertility, and the profusion of vegetable and animal life beggars description. Every tree is clothed with a thousand luxuriant creepers, purple and scarlet-blossomed; they in their turn support myriads of lichens and other verdant parasites. The plants shoot up with marvellous rapidity, and glitter with flowers of the rarest hues and shapes, or bear quantities of luscious fruit, pleasant to the eye and sweet to the taste. The air resounds with the hum of insect-life; through the bright green leaves of the banana skim the sparkling humming-birds, and gorgeous butterflies of enormous size float, glowing with every colour of the rainbow on the flower-scented breezes. But over all this beauty, over the luxuriance of vegetation, over the softness of the tropical air, over the splendour of the sunshine, over the perfume of the flowers, Pestilence has cast her fatal miasmas, and, like the sword of Damocles, the yellow fever hangs threateningly over the head of those who dwell among these lovely scenes. Nature, however, is not to be blamed for this drawback to one of her most charming creations. With better drainage and cleanlier habits amongst its population, there is no reason why Rio should not be a perfectly healthy place. To exorcise the demon who annually scourges its people, no acquaintance with the black art is necessary. The scrubbing-brush and Windsor soap – "this only is the witchcraft need be used." Four days after leaving Rio we arrived at Monte Video, but as we came from an infected port we were put into quarantine, much to our disgust, and were of course unable to go on shore. After we had discharged what cargo we carried for Monte Video, we proceeded to a little island, where we were to land the quarantine passengers, amongst whom was my brother Queensberry, who wanted to stop in Monte Video for a fortnight, following us by the next steamer. The quarantine island, which was a bare rocky little place, did not look at all inviting, and I certainly did not envy my brother his three-days' stay on it. He told me afterwards that he had never passed such a miserable time in all his life, the internal domestic arrangements being most primitive.

The days after leaving Monte Video passed swiftly enough, as it had got comparatively cool, and we were able to have all kinds of games on deck. After seven days at sea, early one morning we sighted Cape Virgins, which commands the north-eastern entrance to the Straits of Magellan. The south-eastern point is called Cape Espiritu Santo; the distance between the two capes being about twenty-two miles. Whilst we were threading the intricate passage of the First Narrows, which are not more than two miles broad, I scanned with interest the land I had come so many thousand miles to see – Patagonia at last! Desolate and dreary enough it looked, a succession of bare plateaus, not a tree nor a shrub visible anywhere; a grey, shadowy country, which seemed hardly of this world; such a landscape, in fact, as one might expect to find on reaching some other planet. Much as I had been astonished by the glow and exuberance of tropical life at Rio, the impression it had made on my mind had to yield in intensity to the vague feelings of awe and wonder produced by the sight of the huge barren solitudes now before me.

After passing the Second Narrows, Elizabeth Island, so named by Sir Francis Drake, came in sight. Its shores were covered with wild fowl and sea-birds, chiefly shag. Flocks of these birds kept flying round the ship, and the water itself, through which we passed, literally teemed with gulls and every imaginable kind of sea-fowl. We were soon abreast of Cape Negro, about fourteen miles from Sandy Point. Here the character of the country suddenly changes, for Cape Negro is the point of the last southerly spur of the Cordilleras, which runs along the coast, joining the main ridge beyond Sandy Point. All these spurs, like the Cordilleras themselves, are clothed with beech forests and thick underwood of the magnolia species, a vegetation, however, which ends as abruptly as the spurs, from the thickly-wooded sides of which, to the completely bare plains, there is no graduation whatever.

As we went along we passed a couple of canoes containing Fuegians, the inhabitants of the Tierra del Fuego, but they were too far off to enable me to judge of their appearance, though I should have liked to have had a good look at them. They are reputed to be cannibals, and no doubt justly so. I have even been told that in winter, when other food is scarce, they kill off their own old men and women, though of course they prefer a white man if obtainable.

At one o'clock we cast anchor off Sandy Point. This settlement is called officially by the Chileans, to whom it belongs, "La Colonia de Magellanes." It was formerly only a penal colony, but in consequence of the great increase of traffic through the Straits, the attention of the Chilian Government was drawn to the importance the place might ultimately assume, and, accordingly, grants of land and other inducements were offered to emigrants. But the colony up to the present has never flourished as was expected, and during a mutiny which took place there in 1877, many of the houses were burned down, and a great deal of property destroyed. As the steamer was to leave in two hours, we began preparations for landing, but meantime the breeze, which had sprung up shortly after our arrival, freshened into a gale, and the sea grew so rough that it was impossible to lower a boat, and the lighters that had come off shore to fetch away cargo dared not go back. The gale lasted all day and the greater part of the night, calming down a little towards three o'clock in the morning. Every effort was accordingly made to get us on shore, the alternative being that we should have to go on with the steamer to Valparaiso, the Company's regulations not allowing more than a certain length of time to be spent at Sandy Point. As may be imagined, we by no means liked the idea of such a possible consummation, and the weather was eagerly scanned, whilst our luggage and traps were being hurried over the sides, as a fresh increase in the strength of the wind would have been fatal.

At last all was ready; we said good-bye to the captain and officers, to whose kindness during the voyage we were so much indebted for our enjoyment of our trip on board the "Britannia" – and climbing down the gangway took our seats in the boat which was to carry us ashore. I felt quite sad as we rowed away, leaving behind us the good ship which we had come to look upon as a home, and for which I at least felt almost a personal affection.

After a long pull, during which the contrary wind and tide bade fair to set at nought the efforts of the four strong sailors who rowed us ashore, we at last came alongside the old tumble-down wooden pier, which forms the landing stage at Sandy Point. We succeeded in reaching its end without incurring any mishap, though we ran considerable risk from the many dangers with which it bristled, in the shape of sudden yawning holes, and treacherously shifting planks. This pier, however, had the merit – a questionable one it is true – of being in keeping with the appearance and condition of the whole colony to which it served as a warning introduction. I suppose there possibly may be drearier looking places than the town of Sandy Point, but I do not think it is probable; and as we walked over the sand-covered beach in front of the settlement, and surveyed the gloomy rows of miserable wooden huts, the silent, solitary streets, where, at that moment, not a single living being was to be seen, save some hungry-looking ostrich-hound, we all agreed that the epithet of "God-forsaken hole" was the only description that did justice to the merits of this desolate place, – nor did subsequent and fuller acquaintance with it by any means induce us to alter this unfavourable opinion.

Proceeding under the guidance of Mr. Dunsmuir, the English Consul, we halted about two hundred yards from the pier, at a house which, we were informed, was the principal shop and inn in the place. It was not an ambitious establishment. Its interior consisted of a ground-floor containing two rooms, of which one served as a shop, and the other as a sitting room. This last apartment we secured as a storeroom for our luggage and equipments, and there also we ate our meals during our sojourn in Sandy Point. The upper portion of this magnificent dwelling was a kind of loft, in one corner of which was a small compartment, which my brother and Mr. B. used as a bedroom. Through the kindness of Mr. Dunsmuir my husband and myself were lodged very comfortably in his own house.

Our first experience of "roughing it," in the shape of the breakfast with which Pedro the innkeeper supplied us, being over, we sauntered up through the grass-grown streets of the colony to the house of Mr. Dunsmuir, from which, as it stands on high ground, we obtained a good view of the Straits and the opposite shores of the Tierra del Fuego. The "Britannia" had already weighed anchor, and for a long time we watched her steaming away through the Straits, till, growing gradually smaller and smaller, she at last disappeared in the haze of the distant horizon. And now that the last link, as it were, of the chain which bound me to old England was gone, for the first time I began to fully realise the fact that we were ten thousand miles away from our home and our friends, alone amidst strange faces and wild scenes; and it required almost an effort to banish the impression that the whole thing was a dream, from which I was presently to awaken and find myself back in England again.

Our anxiety to leave Sandy Point as soon as possible hastened preparations we had to make before starting; but even with every wish to get away, there was so much to be done that we calculated we should not be ready to start for at least four days. There were guides to be found, good dogs to be bought, and, above all, suitable horses to be hired or purchased. Numbers of these latter animals were brought for our inspection, from among which we selected about fifty, of whose merits and failings I shall have to speak at a later occasion. We found the charges for everything ridiculously high, and though no doubt we were cheated on all sides, there was nothing to be done but to accept the prices and conditions demanded, as guides were not plentiful, and the other necessities procurable nowhere else.

A whole day was spent in unpacking the provisions and equipments we had brought from England, and in putting them into canvas bags, so as to be conveniently portable on horseback. For the benefit of those who may contemplate an expedition similar to ours, I give the following list of the articles and provisions we took with us. We limited ourselves, I may say en passant, to such things as were absolutely indispensable, the disadvantages arising from being burdened with unnecessary luggage on such a trip being self-evident: – Two small tents (tentes d'abri), 2 hatchets, 1 pail, 1 iron pot for cooking, 1 frying-pan, 1 saucepan, biscuits, coffee, tea, sugar, flour, oatmeal, preserved milk, and a few tins of butter, 2 kegs of whisky.

To the above we added a sack of yerba maté, of which herb we all grew so fond that we ultimately used it to the complete exclusion of tea and coffee, although at first we by no means agreed with the enthusiastic description of its merits given by Mr. B., at whose recommendation we had taken it.

Our personal outfit consisted, in addition to a few changes of woollen underclothing, in a guanaco-fur mantle, a rug or two, a sheath-knife and revolver; besides, of course, the guns and rifles we had brought for sporting purposes. The cartridges for the latter, of which we had a great number, formed the heaviest item of weight; but notwithstanding the care we had used in our calculations, so as not to take more provisions than we wanted, the goodly pile which was formed when all our luggage was heaped together was rather alarming, and we found that twelve horses at least would be required to carry it. Fortunately we were able to procure three mules, who, between them, carried more than six horses could have done, without, moreover, suffering half as much as the latter in condition from fatigue, or the severe heat which we occasionally encountered.

We selected our guides from among a number who offered their services. We chose four; two Frenchmen, an Argentine gaucho, and a nondescript creature, an inhabitant of Sandy Point, I'Aria by name, who had accompanied Captain Musters on his expedition. This I'Aria was a dried-up-looking being of over sixty, but he proved a useful servant, notwithstanding his age. He was a beautiful rider; and, considering his years, wonderfully active and enduring. As long as we remained in Sandy Point, however, he was of little use to us, as he was never by any chance sober, though, strange to say, when once we left the settlement, he became a total abstainer, and stoutly refused, during the whole of the trip, to take any liquor that was offered to him. His face, the skin of which, from long exposure to wind and weather, had acquired the consistency of parchment, was one mass of wrinkles, and burnt almost black by the sun, while the watchful, cunning expression of his twinkling bead-like eyes added to his wild appearance, the Mephistophelian character of which earned for him the sobriquet of "The devil's agent for Patagonia." He had passed more than forty years of his life on the pampa, and was, therefore, well qualified to act as guide. Of the others, Gregorio gave us most satisfaction, and served us all through the trip with untiring zeal and fidelity. He was a good-looking man, of about forty, and added to the other accomplishments of his craft as gaucho, a slight knowledge of English. His ordinary occupation was that of an Indian trader, and at one time of his career he had owned a small schooner, with which he used to go seal-hunting in the season. One of the Frenchmen, François, whose original profession had been that of a cook, proved most useful to us in that capacity, and played the changes on what would otherwise have been a slightly monotonous diet of guanaco and ostrich meat, in a marvellous manner. His career, like Gregorio's, had been a chequered one. After having served during the Franco-Prussian war as a Chasseur d'Afrique, he left his country with three companions to start some business in South America, on the failure of which he turned his attention to ostrich-hunting. He was a cheery, handsome little fellow, and was possessed, moreover, of an excellent voice, and whether at work by the camp-fire, or riding on the march, was always to be heard singing merrily. He owned two very good ostrich-dogs; one, a handsome Scotch deer hound called "Leona," the other a black wiry dog called "Loca," a cross between an African greyhound and an English lurcher. Gregorio had only one dog, but it was the best of the lot, often managing to run down an ostrich singly, a feat which requires immense stamina and gameness, and which none of the other dogs were able to perform.

As to Guillaume I need say nothing, except that all our party disliked him very much.

After four days' hard work our preparations for departure were nearly completed, though a little yet remained to be done. Anxious, however, to get out of Sandy Point, we resolved to start off with the greater part of the packs and horses, and to await the coming of the remainder in the beech-wood at Cabo Negro, some fifteen miles away from the colony.

CHAPTER IV.

THE START FOR CAPE NEGRO – RIDING ALONG THE STRAITS – CAPE NEGRO – THE FIRST NIGHT UNDER CANVAS – UNEXPECTED ARRIVALS – OUR GUESTS – A NOVEL PICNIC – ROUGH-RIDING – THERE WAS A SOUND OF REVELRY BY NIGHT.

EARLY in the morning the horses were driven up and saddled, some trouble being experienced with the pack-mules, who were slightly restive, taking rather unkindly to their loads at first.

As our guides were busy hunting up the requisite number of horses, and finishing their preparations for the journey, we took another man with us for the time that we should have to remain at Cabo Negro, as well as a little boy, a son of Gregorio's, to help to drive the horses along. After a hurried breakfast we got into the saddle; the pack-horses were driven together, not without a great deal of trouble, for they were as yet strangers to each other, and every now and then one or two would bolt off, a signal to the whole troop to disperse all over the place, so that nearly an hour had elapsed before we had got well clear of the colony, and found ourselves riding over an undulating grassy stretch, en route for the pampas.

Our way lay over this plain for about an hour, and then, having forded a small stream, we entered the outskirts of the beechwood forests that line the Straits. The foliage of the trees was fresh and green, the sky clear and blue, the air sun-lit and buoyant, and everything seeming to augur favourably for the success of our trip, we were all in the best of spirits.

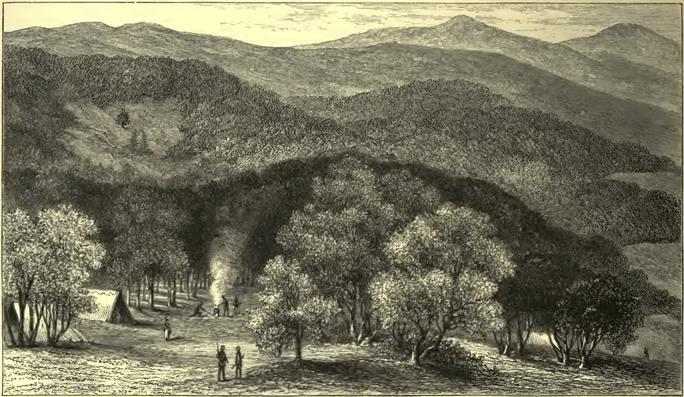

THE STRAITS OF MAGELLAN.

Our road presently brought us down to the Straits of Magellan, along whose narrow strip of beach, in some places barely three yards broad, we had now to ride in single file. Along the coast the land terminates abruptly, and the trees and bushes form an impenetrable thicket, which comes down almost to the water's edge. Point after point shoots out into the sea, each bearing a monotonous resemblance to the other, though, as we advanced, the vegetation that covered them grew more and more stunted and scanty, till at last the trees and bushes disappeared altogether, and after a three hours' ride we found ourselves journeying along under the shadow of some steep bluffs, on which the only vegetation was a profusion of long coarse grass. Innumerable species of gulls and albatrosses were disporting themselves on the blue water, and seemed little alarmed at our approach, lazily rising from the water a moment as we went past them, to resume almost immediately their fishing operations. All along the beach, carried there by the sea from the opposite side, I noticed great quantities of the cooked shells of crayfish, the remains of many a Fuegian-Indian meal. The Tierra del Fuego itself was distinctly visible opposite, and at different points we could see tall columns of smoke rising up into the still air, denoting the presence of native encampments, just as Magellan had seen them four hundred years before, giving to the island, on that account, the name it still bears.

At Cabo Negro we stopped for a moment at a little farmhouse, and partook of some maté, which was hospitably offered us by the farmer's wife, and then mounting again, we galloped over a broad grassy plain where some sheep and cattle were grazing, till we came to a steep, wooded hill. On its crest, under some spreading beeches, we resolved to pitch our camp, water being near at hand, and the position otherwise favourable. In a short time the pack-horses were relieved of their loads, and neighing joyfully, they galloped away to graze in the plain we had just crossed. Our tents were pitched, and having made up our beds in them, so as to have everything ready by night-time, we began to set about preparing dinner. Wood being abundant, a roaring fire was soon blazing away cheerily, some meat we had brought from Sandy Point was put into the iron pot, together with some rice, onions, etc., and then we lay down round the fire, not a little fatigued by our day's exertions; but inhaling the grateful odours arising from the pot, with the expectant avidity of appetites which the keen Patagonian air had stimulated to an unusual extent.

By the time dinner was over night had set in. The moon had risen, and the clear star-lit sky gave assuring promises of a continuance of fine weather. A slight breeze stirred the branches overhead, and in the distance we could hear the lowing of the cattle on the plains, and the faint tinkling of the bells of the brood-mares. The strange novelty of the scene seemed to influence us all, and the men smoked their pipes in silence. Before going to bed I went for a short stroll to the shores of a broad lagoon which lay at the foot of the hill on which our camp was pitched. Its waters glittered brightly in the moonlight, but the woods which surrounded it were sombre and dark. Occasionally the sad plaintive cry of a grebe broke the silence, startling me not a little the first time I heard it, for it sounds exactly like the wail of a human being in pain. Going back to the camp I found my companions preparing to go to bed, an example I was not slow to follow, and soon, wrapt up in our guanaco-fur robes, with our saddles for pillows, we were all fast asleep.

It had been agreed that the next morning one of our party should go back to Sandy Point, to see how the guides were getting on, and Mr. B. having volunteered to perform that task, I rose at an early hour to get him his breakfast and see him off on his journey. Then, whilst my brother and husband went out with their guns to shoot wild-duck, I busied myself writing a few last letters to friends at home. This done, I rode down to the Straits, and had a plunge into the water, but it was so cold that I got quite numbed, and with difficulty managed to dry and dress myself. Late in the afternoon the sportsmen returned, bringing an excellent bag with them, and we speedily set about plucking a few birds, and making other preparations for dinner. Just as, that meal being over, we had settled ourselves comfortably round the fire, prepared lazily to enjoy the lovely evening, our camp-servant, who had been on the look-out for the return of Mr. B., reported that a troop of about ten horsemen were coming our way. As Indian traders do not go out to the pampas in such large parties, he was quite at a loss to imagine who the people could be who were riding out so late at night, especially as they had no pack-horses with them. We all got up and went to have a look at these mysterious horsemen. As they approached the foot of our hill we could see that they were all armed with guns and rifles, a circumstance which began to suggest unpleasant recollections of the last Sandy Point mutiny. Could it be that another outbreak had occurred, and that these men were escaping to the pampas? If so, they might possibly make a descent on us in passing, and supply any deficiencies in their own outfit from ours. This was a rather startling state of affairs, and we were hurriedly holding counsel as to what was the best course to take under the circumstances, when our dogs suddenly started up, and began barking furiously. Then came the sound of horses' hoofs, and brushing through the tall furze, two horsemen galloped straight towards our camp, followed, as the sound of voices told us, by the rest of the party. In another second the two foremost ones reined up in front of us, turning out to be, not bloodthirsty mutineers, but Mr. Dunsmuir and Mr. Beerbohm. A few words explained all. The party was composed of some officers of the "Prinz Adalbert," a German man-of-war, which had anchored at Sandy Point that morning, Mr. B. having gone on board and invited them out to our camp for a day's shooting. Delighted at this solution of the situation, we hurried to welcome our new guests, who now arrived tired and hungry after their long ride. Among their number were H.I.H. Prince Henry of Prussia, who was on a cruise in the "Prinz Adalbert," and her commander, Captain Maclean.

Fresh logs were added to the blazing fire, meat was set to roast, soup put on to cook, and every preparation made for a good supper – an easy task, as the officers had brought plentiful supplies of all kinds of provisions with them. We then lay round the fire, the new-comers evidently quite charmed by our cosy sylvan quarters, and by the novelty of the strange picnic, which they had little anticipated making in Patagonia, of all places in the world.

I was much amused at Mr. B.'s account of how the expedition had been initiated. He had got into Sandy Point at about nine o'clock, and at ten the "Prinz Adalbert" was signalled in the offing.

As soon as she had cast anchor he went on board, having been previously acquainted with the captain, and at breakfast explained his presence in such an out-of-the-way part of the world as Sandy Point, by an account of our intended trip, and finally asked the captain and the officers to come out to our camp and try for themselves what open-air life in Patagonia was like. He had little difficulty in persuading them to accept his offer, and whilst the officers made their preparations, he went on shore to hunt up ten horses, the number required. This was an easy matter; but it was another thing to find as many saddles, for, though many people in Sandy Point own numbers of horses, few have more than one saddle, and such being the case, they are loth to lend what at any moment may be of pressing necessity for themselves. However, by dint of ingenious combinations, some kind of an apology for a saddle was fitted to each horse, and the whole party at last set off on their trip in high spirits, and very well pleased with everything. Each officer carried a blanket or rug with him, and, as some shooting was expected, a gun and some ammunition. For the first two hours all went well, the air was warm and sunny, the scenery novel and interesting, and a zest was given to the expedition by its unconventional character and the suddenness with which it had been improvised.

But after a time the hard action of the horses and the roughness of some of the saddles began to have their effect, especially as many of the officers were little accustomed to riding. Occasionally Mr. B. would be asked, at first in tones of implied cheerful unconcern, "How far is it to the camp?" To this question he would reply by a wave of the hand in the direction of one of the many points which shoot out along the Straits, saying, "A little beyond that point." Then, as point after point was passed, and the answer to inquiries still continued, as before, "A little beyond that point," gradually the laughter and chat which had enlivened the outset of the trip grew more constrained, occasional lapses of complete silence intervening. Now and then one of the riders would move uneasily in the saddle and sigh – and on the faces of many (especially of those who rode stirrupless saddles) fell in time an expression of fixed resignation to suffering, which was not unheroic. Mr. B. observed all this, and his conscience began to smite him. At starting, in an amiable endeavour to put everything in a rosy light, he had slightly understated the distance to our camp, and now the terrible consequences of his rashness were already visiting him. The quasi-martyrs whom he was leading, it was but too evident, were only bearing up against suffering by the comforting consciousness that they must be close to the camp. He could not undeceive them; he felt himself woefully wanting in courage enough to break the truth; and yet the only alternative was to go on repeating the now to him, as to everybody else, hateful formula, "A little beyond that point." His victims could only imagine one thing – that he had lost the way, though in fact he knew the road and its length only too well. Never, as he said, had it been so palpably brought before him that the way to hell is paved with good intentions; and his intentions, when mystifying the party as to the length of the road, had been of the best.

However, all things come to an end, and at last, with a feeling of deep relief, he was able to point out our hill to the weary saddle-worn band, whose advent, as possible mutineers, had thrown us into such a panic.

By the time Mr. B. had finished his story supper was ready, and that important fact having been duly announced, our hungry guests fell to, and made a hearty meal. The strain which their number put on the capabilities of our batterie de cuisine was fortunately relieved by a profusion of tinned provisions of all kinds which they had wisely brought with them, and under those Patagonian beeches, together with the native mutton, were discussed asperges en jus, which had attained their delicate flavour under the mild fostering of a Dutch summer, patés elaborated far away among the blue Alsatian mountains, and substantial, though withal subtly flavoured, sausages from the fatherland itself. After supper pipes were lit, and the wine-cup went round freely, the woods resounding with laughter and song till nearly midnight, by which time most of the party were beginning to feel the effects of their day's exertions, and to long for bed. In one of our tents we managed to make up four couches, on which the Prince, the Captain, Count Seckendorff, and another officer respectively laid their weary limbs, and went to sleep as best they might. The Captain, a strong stout man, had suffered more than any one from the ride, and it must have been a moot question in his secret heart whether the day's enjoyment had not been somewhat dearly purchased.

The others kept up the ball still later, and it must have been quite two o'clock before the last convive rolled himself up in his blanket by the fire, and silence fell over our camp. At about that hour I peered out of my tent at the scene. Round a huge heap of smouldering logs, in various attitudes, suggestive of deep repose, lay the forms of the sleepers whom chance had thus strangely thrown together for one night. Our dogs had risen from their sleep, and in their turn were making merry over whatever bones or other fragments of the feast they managed to ferret out. A few moonbeams struggled through the canopy of leaves and branches overhead, throwing strange lights and shadows over the camp, and the weird effect of the whole scene was heightened by the mysterious wail of the grebe, which at intervals came floating up in the air from the lake below, like the voice of an unquiet spirit.

CHAPTER V.

DEPARTURE OF OUR GUESTS – THE START FOR THE PAMPAS – AN UNTOWARD ACCIDENT – A DAY'S SPORT – UNPLEASANT EFFECTS OF THE WIND – OFF CAPE GREGORIO.

THE sun had hardly risen the next morning ere our little camp was again astir. Making a hasty toilet I stepped out and found that our guests had all risen, and were busy in getting their guns and shooting accoutrements ready for the coming sport. As soon as they had partaken of some coffee, the whole party started off to the plains below, and for an hour or so, till their return, the repeated reports of their guns seemed to indicate that they were having good sport. Towards breakfast-time they came back, fairly satisfied with their morning's work, though I am inclined to attribute this satisfaction to their evident desire to look at everything connected with their picnic from an optimist point of view, as their bag was in reality a very small one, consisting only of a few brace of snipe and wild-duck. We then set to work to get a good breakfast ready, at which employment Prince Henry lent an intelligent hand, turning out some poached eggs in excellent style. We had a very pleasant meal, the officers expressing great regret that they were unable to prolong their stay in our beechwood quarters, the steamer being obliged to continue her journey that evening. Whilst they smoked a last pipe, the horses were driven up and saddled, and at about eight o'clock, Mr. B. and myself accompanying them as guides, they mounted and set out on the road homeward.

The stiffness consequent on their exertions of the previous day must have made the sensations they experienced on returning to the saddle anything but pleasant ones, and at the start a decidedly uncheerful spirit seemed to prevail among them; but as we cantered along, and they warmed to their work, this uneasiness disappeared, and soon all were as merry as possible. The day was lovely, and the scenery looked to the best advantage, the only drawback to our enjoyment of the ride being that the sun was rather too hot.

After we had gone several miles we got off our horses to rest under the shade of some trees, by the side of a little stream which came bubbling out of the cool depths of the forest, emptying itself into the adjacent Straits. Here an incident occurred which might have been attended with inconvenient consequences. One of the officer's horses suddenly took it into its head to trot off, and, before any one could stop it, disappeared round a point in the direction of Sandy Point. Mr. B. got on his horse and started in pursuit, and in the meanwhile a time of some suspense ensued, for, in the event of his being unsuccessful, some unfortunate would have had to make the best of his way on foot. However, this unpleasant contingency was happily avoided; Mr. B. soon reappeared, having managed to catch the runaway, not indeed without a great deal of trouble.

We reached Sandy Point late in the afternoon, and very glad the whole party must have been to get there, for they were most of them completely done up, and, considering the length of the ride, their rough horses and rougher saddles, this was no wonder.

After having said good-bye to the officers, with many expressions of thanks on their part for the unexpected diversion our presence in that outlandish part of the world had afforded them, Mr. B. and I immediately set out to return to the camp, which we managed to reach just as it was getting dark.

Everything was now ready for our journey, and it was resolved that we should make a start the next morning. We were therefore up early, in order to help the guides as much as possible with the packing, which was quite a formidable undertaking. It took fully three hours to get our miscellaneous goods and chattels stowed away on the pack-horses, whose number was thirteen. At last, however, all was ready; we got into the saddle, and with a last glance at the beechwood camp, which had grown quite familiar and home-like to us, we rode off, now fairly started on our journey into the unknown land that lay before us. We soon had our hands full to help the guides to keep the horses together, a rather difficult task. The mules in particular gave great trouble, and were continually leading the horses into mischief. At one time, as if by preconcerted signal, the whole troop dispersed in different directions into the wood, and there, brushing through the thick underwood, many of the pack-horses upset their packs, and trampled on the contents, whilst some of the others turned tail, and coolly trotted back to the pasture-ground they had just left at Cabo Negro.

All this was very provoking, but, with a little patience and a good deal of swearing on the part of the guides, the refractory pack-horses were re-saddled, the troop was got together again, and by dint of careful driving we at last got safely out of the wooded country, and emerged on the rolling pampa, where there was for some distance a beaten Indian track, along which the horses travelled with greater ease, till, gradually understanding what was required of them, they jogged on in front of us with tolerable steadiness and sobriety, which was only occasionally disturbed by such slight ebullitions as a free fight between two of the stallions, or an abortive attempt on the part of some hungry animal to make a dash for some particularly inviting-looking knoll of green grass at a distance off the line of our march.

The country we were now crossing was of a totally different character to that we had left behind us. Not a tree or a shrub was to be seen anywhere, and while to the left of us lay the rugged range of the Cordilleras, in front and to the right an immense plain stretched away to the horizon, rising and falling occasionally in slight undulations, but otherwise completely and monotonously level. The ground, which was rather swampy, was covered with an abundance of coarse green grass, amongst which we could see flocks of wild geese grazing in great numbers. We passed several freshwater lakes, covered with wild-fowl, who flew up very wild at our approach. A hawk or two would occasionally hover over our heads, and once the dogs started off in pursuit of a little grey fox that had incautiously shown itself; but except these, there was no sign of animal life on the silent, seemingly interminable plain before us.

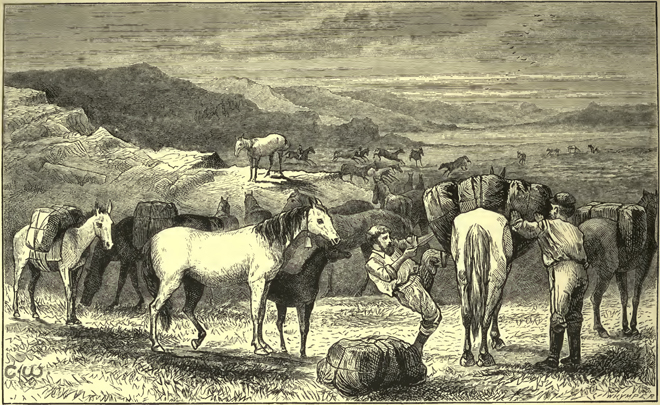

"COLLECTING THE 'TROPILLA' – SADDLING UP."

After we had ridden for several hours, we turned off to the left, facing the Cordilleras again, and soon the plain came to a sudden end, a broken country now appearing, over which we rode till nightfall, when we came in sight of the "Despuntadero," the extremity of Peckett's Harbour, an arm of the sea which runs for some distance inland. Here we were to camp for the night, and as we were all rather tired and hungry after our long ride, we urged on our horses to cover the distance that still lay between us and our camping-place as quickly as possible. But to "hasten slowly" would have been a wiser course in this case, as in most others. The rapid trot at which we now advanced disturbed the equilibrium of one of the packs, the cords holding which had already become slack, and down came the whole pack, iron pot, tin plates, and all, with an awful clatter, whilst the mare who carried it, terrified out of her wits, dashed off at a gallop, spurring with her heels her late encumbrances, and followed by the whole troop of her equally frightened companions.

The pampa was strewn with broken bags; and rice, biscuits, and other precious stores lay scattered in all directions. When we had picked up what we could, and replaced the pack on the mare, who in the meantime had been caught again, we were further agreeably surprised by the sight of another packless animal galloping over the brow of a distant hill, followed at some distance by Gregorio, who was trying to lasso it, whilst I'Aria was descried in another direction, endeavouring to collect together another scattered section of our troop. Off we scampered to aid him, turning on the way to drive up one of the mares, whom we accidentally found grazing with her foal in a secluded valley, "the guides forgetting, by the guides forgot."

By the time we got up to I'Aria, the obstinacy and speed of the refractory animals had evidently proved too much for him, inasmuch as we found him sitting under a bush philosophically smoking a pipe. In answer to our query as to what had become of the horses, he waved his hand vaguely in the direction of a distant line of hills, and we were just setting off on what we feared would prove a rather arduous quest when a welcome tinkle suddenly struck our ears, and the troop reappeared from the depths of a ravine, driven up by Francisco, who had providentially come across them in time to intercept their further flight.

It was quite dark as we rode down and pitched our camp by the shore of the inlet above mentioned, under the lee of a tall bluff, not far from a little pool of fresh water. After the tents had been set up some of the men went to look for firewood, but there was a scarcity of that necessary in the region we were now in, and the little they could collect was half green. However, we managed to make a very fair fire with it, and our dinner was soon cooked and eaten, whereupon we retired to rest.

The next morning was fine, and we resolved to stop a day at our present encampment and have some shooting, – game, as Gregorio informed us, being plentiful in that region. After a light breakfast we took our guns and started off in the direction of a group of freshwater lakes which lay beyond a range of hills behind our camp. We were rewarded for our arduous climb by some excellent sport, wild geese, duck, etc., being very plentiful, and on our way back we crossed some marshy ground where there were some snipe, several brace of which we bagged. In the afternoon, it being rather hot and sultry, we refreshed ourselves with a bath in the sea, and then came dinner-time, and by half-past seven we were in bed and asleep.

The following day we continued our journey northward. A long day's ride brought us to some springs, called "Pozos de la Reina," where we camped for the night. After we had rested for a short time round the fire, and had leisure to look at one another, we became aware of a most disagreeable metamorphosis that had taken place in our faces. They were swollen to an almost unrecognisable extent, and had assumed a deep purple hue, the phenomenon being accompanied by a sharp itching. The boisterous wind which we had encountered during the day, and which is the standing drawback to the otherwise agreeable climate of Patagonia, was no doubt the cause of this annoyance, combined possibly with our salt-water bath of the day previous.

After a few days the skin of our faces peeled off completely, but the swelling did not go down for some time. I would advise any person who may make the same journey to provide themselves with masks; by taking this precaution they will save themselves a great deal of the discomfort we suffered from the winds.

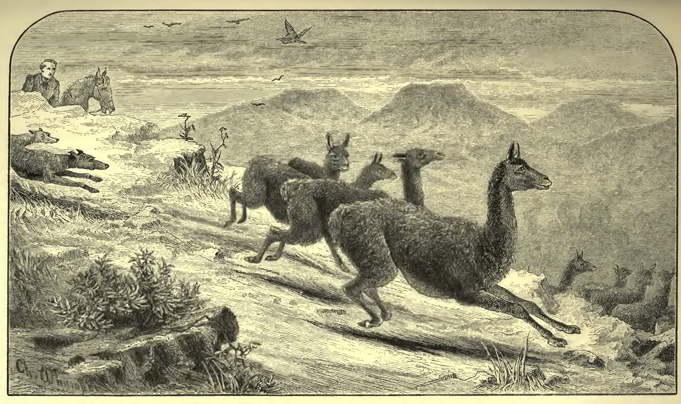

The following day we left "Pozos de la Reina," and pushed forward as quickly as possible, as we had no meat left, and had not yet arrived in the country of the guanacos and ostriches. The Indians had very recently passed over all the ground we were now crossing, and, as usual, had swept away any game there might have been there.

The range where guanaco really become plentiful is about eighty miles away from Sandy Point. Still we kept a good look-out, and any ostrich or guanaco that might have had the misfortune to show itself would have stood a poor chance of escape with some eight or nine hungry dogs and a number of not less keen horsemen at its heels.

But the day wore on, and we arrived at our destination empty-handed. The spot we camped at lay directly in front of Cape Gregorio, which was hazily visible in the distance. There was an abundance of wood in the locality, and the Indian camp being not far off, we were conveniently situated in every respect, as we intended paying these interesting people a visit before continuing our journey.

CHAPTER VI.

VISIT TO THE INDIAN CAMP – A PATAGONIAN – INDIAN CURIOSITY – PHYSIQUE – COSTUME – WOMEN – PROMINENT CHARACTERISTICS – AN INDIAN INCROYABLE – SUPERSTITIOUSNESS.

SINCE we left Sandy Point our dogs had had no regular meal, and had subsisted chiefly on rice and biscuits, a kind of food which, being accustomed to meat only, was most uncongenial to their tastes and unprofitable to their bodies. For their sakes, therefore, as well as for our own, we looked forward to our visit to the Indian camp, apart from other motives of interest, in the hopes of obtaining a sufficient supply of meat to last for all of us, until we should arrive in the promised land of game.

After breakfast the horses were saddled, and taking some sugar, tobacco, and other articles for bartering purposes, we set out for the Indian camp, accompanied by Gregorio and Guillaume. I'Aria and Storer were left in charge of our camp, and Francisco went off with the dogs towards Cape Gregorio, in the hope of falling in with some stray ostrich or guanaco. The weather was fine, and for once we were able to rejoice in the absence of the rough winds which were our daily annoyance. We had not gone far when we saw a rider coming slowly towards us, and in a few minutes we found ourselves in the presence of a real Patagonian Indian. We reined in our horses when he got close to us, to have a good look at him, and he doing the same, for a few minutes we stared at him to our hearts' content, receiving in return as minute and careful a scrutiny from him. Whatever he may have thought of us, we thought him a singularly unprepossessing object, and, for the sake of his race, we hoped an unfavourable specimen of it. His dirty brown face, of which the principal feature was a pair of sharp black eyes, was half-hidden by tangled masses of unkempt hair, held together by a handkerchief tied over his forehead, and his burly body was enveloped in a greasy guanaco-capa, considerably the worse for wear. His feet were bare, but one of his heels was armed with a little wooden spur, of curious and ingenious handiwork. Having completed his survey of our persons, and exchanged a few guttural grunts with Gregorio, of which the purport was that he had lost some horses and was on their search, he galloped away, and, glad to find some virtue in him, we were able to admire the easy grace with which he sat his well-bred looking little horse, which, though considerably below his weight, was doubtless able to do its master good service.

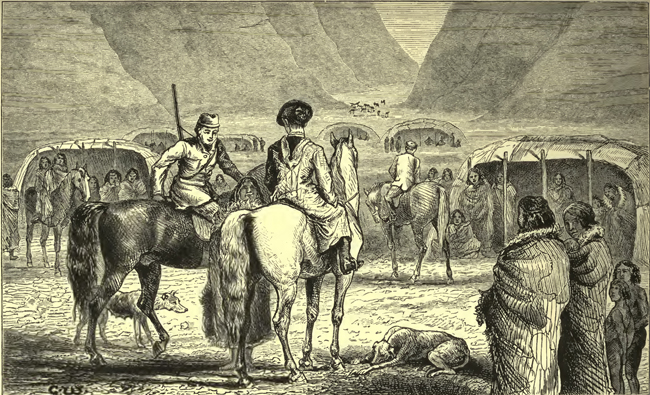

Continuing our way we presently observed several mounted Indians, sitting motionless on their horses, like sentries, on the summit of a tall ridge ahead of us, evidently watching our movements. At our approach they disappeared over the ridge, on the other side of which lay their camping-ground. Cantering forward we soon came in sight of the entire Indian camp, which was pitched in a broad valley-plain, flanked on either side by steep bluffs, and with a little stream flowing down its centre. There were about a dozen big hide tents, in front of which stood crowds of men and women, watching our approach with lazy curiosity. Numbers of little children were disporting themselves in the stream, which we had to ford in order to get to the tents. Two Indians, more inquisitive than their brethren, came out to meet us, both mounted on the same horse, and saluted us with much grinning and jabbering. On our arrival in the camp we were soon encircled by a curious crowd, some of whose number gazed at us with stolid gravity, whilst others laughed and gesticulated as they discussed our appearance in their harsh guttural language, with a vivacious manner which was quite at variance with the received traditions of the solemn bent of the Indian mind. Our accoutrements and clothes seemed to excite great interest, my riding-boots in particular being objects of attentive examination, and apparently of much serious speculation. At first they were content to observe them from a distance, but presently a little boy was delegated by the elders, to advance and give them a closer inspection. This he proceeded to do, coming towards me with great caution, and when near enough, he stretched out his hand and touched the boots gently with the tips of his fingers. This exploit was greeted with roars of laughter and ejaculations, and emboldened by its success, many now ventured to follow his example, some enterprising spirits extending their researches to the texture of my ulster, and one even going so far as to take my hand in his, whilst subjecting a little bracelet I wore to a profound and exhaustive scrutiny.

INDIAN CAMP.