Leaves from

Mrs. Ewing's "Canada Home."

CHAPTER I.

that sweet writer, JULIANA HORATIA EWING, whose busy pen was not long since laid aside, but whose memory lives with us in the pages of some of the best loved and brightest stories in the English language, these are a few memories and facts of that portion of her life spent on this side of the Atlantic, — a sort of gleaner's sheaf, from the rich field of that life already gone over and stored by her sister, Miss H. K. Gatty, 1 who, however, in her interesting work has left almost untouched the record of the two years in Canada. So that with the aid of loving memories held by her many old friends there, together with some of her own charming letters written "Home" at that time, we have many things of interest to tell.

that sweet writer, JULIANA HORATIA EWING, whose busy pen was not long since laid aside, but whose memory lives with us in the pages of some of the best loved and brightest stories in the English language, these are a few memories and facts of that portion of her life spent on this side of the Atlantic, — a sort of gleaner's sheaf, from the rich field of that life already gone over and stored by her sister, Miss H. K. Gatty, 1 who, however, in her interesting work has left almost untouched the record of the two years in Canada. So that with the aid of loving memories held by her many old friends there, together with some of her own charming letters written "Home" at that time, we have many things of interest to tell.

In the small provincial city of Fredericton, New Brunswick, she spent two years of her earnest life, writing there many of her sweetest stories; and we find, in following her footsteps and in reading her letters, how deeply she loved the quaint old town whither she came, a stranger and a bride, with her husband, Major Ewing, when his regiment, the twenty-second of England, was ordered there in 1867.

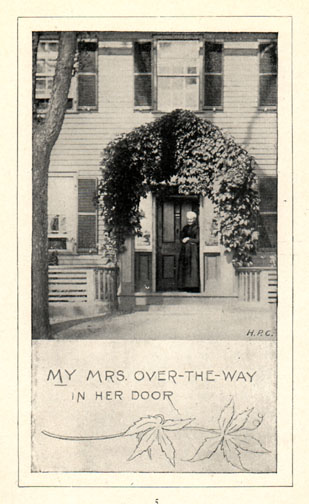

Her dearest friend there, Margaret Medley, wife of the late Bishop Medley of Fredericton, has been to me a veritable "Mrs. Over-the-Way" in giving me of her "remembrances," as little Ida in that story would say; and to her thanks are due for the delightful letters, as well as the interesting set of water colors drawn by Mrs. Ewing's own hand. These were done, in fact, especially for her revered and beloved friend the Bishop of Fredericton, and were given to him on her departure for England. Her love and esteem for these two friends can readily be seen by the frequent mention of them in these letters "Home." It was to them she dedicated her book, "A great Emergency," and she keenly enjoyed her study of Hebrew with the Bishop, who in his turn was greatly impressed by the quick mind and retentive memory of his pupil.

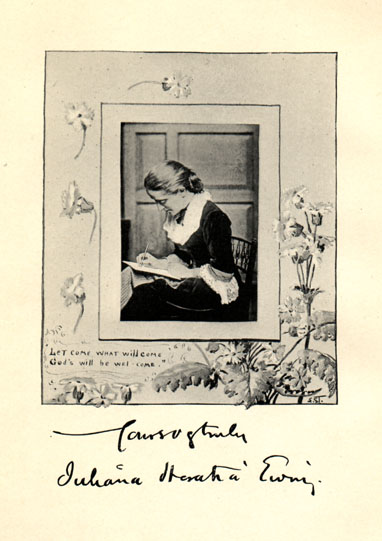

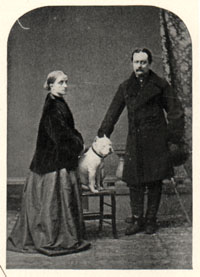

Mrs. Ewing is described as having an earnest face, with deep set, "thinking eyes," while her slight form seemed almost too frail and small to carry the abundant crown of golden hair worn in plaits coiled at the back of her head.

Can one not almost see her, sitting as in her photograph here, that earnest face bending over the papers on her lap, — writing, writing, writing the lovely thoughts which flowed so readily and continually from her magic pen?

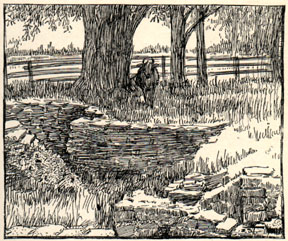

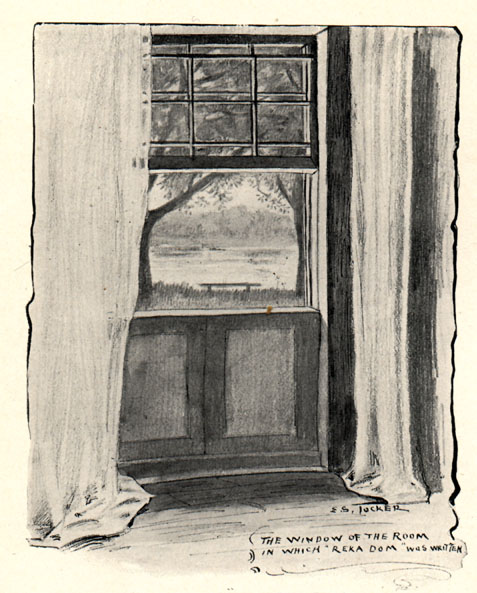

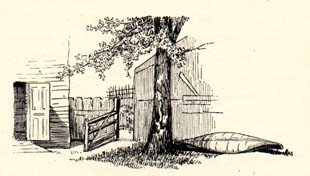

The Ewings occupied three or four different homes during their two years' stay in Fredericton, but the favorite one was that which I can see from my window here, with its three gray old willow sentinels. She often speaks of this house in her letters, how much she enjoyed her life there. She called it "Reka Dom" — House by the River, — for it stands on the bank of the river St. John, across the road from three old willows. There she wrote her story of "Reka Dom," and here is a sketch of the window in her room, — probably the very one by which she sat when writing.

Once when she and her husband were walking on the river bank not long after their arrival in Fredericton, seeing this old shambling house — which she describes in one of her letters, — she expressed a wish to live in it; and they moved there as soon as they could get possession. How she must have enjoyed the beautiful St. John River flowing in front of their windows, guarded by the rows of old willows! Her room is in the lower right-hand corner, with the closed shutters.

MRS. EWING'S HOUSE, "REKA DOM."

I think that dog "Nox," in "Benjy in Beastland," must have had his "improvised morgue," for the "bodies" he found in the river, under that very old willow which still stretches out over the river its "finger-like" leaves. This is what she says of it in that story: "Near the dog's home ran a broad, deep river. Here one could bathe and swim most delightfully. Here also many an unfortunate animal found a watery grave. There was one place from which (the water being deep and the bank convenient at this spot) the poor wretches were generally thrown.... Hither at early morning Nox would come, in conformity with his own peculiar code of duty, which may be summed up in these words: 'Whatever does not properly or naturally belong to the water, should be fetched out.'... Not far from the spot I have mentioned, an old willow tree spread its branches widely over the bank, and here and there stretched a long arm, and touched the river with its pointed fingers. Under the shadow of this tree was the morgue, and here Nox brought the bodies he rescued from the river, and laid them down."

I think that dog "Nox," in "Benjy in Beastland," must have had his "improvised morgue," for the "bodies" he found in the river, under that very old willow which still stretches out over the river its "finger-like" leaves. This is what she says of it in that story: "Near the dog's home ran a broad, deep river. Here one could bathe and swim most delightfully. Here also many an unfortunate animal found a watery grave. There was one place from which (the water being deep and the bank convenient at this spot) the poor wretches were generally thrown.... Hither at early morning Nox would come, in conformity with his own peculiar code of duty, which may be summed up in these words: 'Whatever does not properly or naturally belong to the water, should be fetched out.'... Not far from the spot I have mentioned, an old willow tree spread its branches widely over the bank, and here and there stretched a long arm, and touched the river with its pointed fingers. Under the shadow of this tree was the morgue, and here Nox brought the bodies he rescued from the river, and laid them down."

This river was a great source of joy and pleasure to her beauty-seeing eye; and over its lovely waters the richly toned Cathedral chimes, and the bugle note from the barracks, tell the time of day, and ring out calls to worship to-day, just as they did when she lived in this house on its banks. This view she constantly enjoyed while they lived in that river house, — looking down the river from the porch, — and she refers to its loveliness in her letters.

Along this river bank of a Sunday evening the soldier and his lass stroll to-day, with utter unconcern for the passing beholder, as they did then, making picturesque bits of red coat and white gown against the blue river-line, — the red of coat seeming to be compelled to keep the rules of true picture-making by carrying a line of the red across a certain narrow place on the white.

VIEW OF THE RIVER FROM PORCH OF "REKA DOM."

It is just the same to-day; and seemingly the very same children play under the willows, with their dog friends, and drive cows leisurely along early in the morning and late at night.

RUINS OF OLD ROSE HALL, WHERE BENEDICT ARNOLD ONCE LIVED AND MRS. EWING STAYED.

Mrs. Ewing had another home on the bank of the St. John — much farther "down river" (as they say) than "Reka Dom." There she occupied the large drawing-room in an interesting old house known as "Rose Hall," and noted for its lovely river view and the fine old trees about its grounds. This place is of historic interest also, for it was there that the traitor Benedict Arnold lived while in Canada. A pile of ruins is now all that is left of the place (which was destroyed by fire years ago). Here once was heard the martial tread of this mysterious man as he walked up and down in meditation bent, and here our little lady trod the trees and flowers among; here the weeds pathetically wave over the crumbled hearth-stones, and the cows graze all about, while birds undisturbed build in the trees overhead, and countless crickets chirp their everlasting note of the "unchangeable" under all the seeming change of this busy world.

CHAPTER II.

an amusing anecdote is recalled of the industry and dauntless energy of this "little body with the great heart" (as her sister tells us she is described by a friend) who desired to do all things.

an amusing anecdote is recalled of the industry and dauntless energy of this "little body with the great heart" (as her sister tells us she is described by a friend) who desired to do all things.

A story is told of one of the houses she occupied having such an offensive wall paper as to offend her artistic eye; and on her complaining of it to a Canadian visitor, this latter said, half in fun, that of course a Canadian girl would be able to get over the difficulty by papering the room herself, but she supposed an English girl would not know how, as, in her opinion, "English girls had only two left hands and no head."

This at once caused our little lady, and her friend Mrs. Medley, to resent the implied discredit to the Old World training of a girl, and they at once resolved to show what an "English girl" could do if her powers were put to the test.

She accordingly bought "a delicate, useless, lavender-tinted wall paper" (as I was told), and though she did not probably know the difference between a "hanger" and a whitewash brush, she nevertheless proceeded to put up that paper. Of this paper-hanging she gives such a bright account in a letter — that of Oct. 12, 1868 — that one has the whole picture. But she does not add what was told to me by an onlooker — (in fact, the very caller whose remarks upon English girls called forth the event) — that while the two intrepid ladies were hurrying up their work, to have it done when Major Ewing should come home, he suddenly and unexpectedly appeared. At his emphatic exclamation of amazement, on seeing them on tall ladders wielding brushes in such a professional manner, his little wife, who had just finished what she considered her greatest achievement on that wall, — the pasting over the chimney, — was overcome by her laughter. Standing on the mantlepiece as she was, she had to bend forward to recover her balance, and leaning against that "lovely" paper, left the print of a pasty apron and hands in the very centre! The house is little changed, but oh, that that print of apron and hands could now be seen over the hearth-stone!

CHAPTER III.

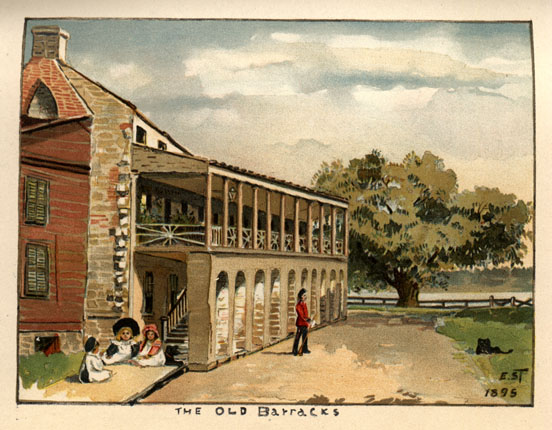

Ewing had his office in a small red brick building joining the old gray barracks now occupied by the officers and their families.

Ewing had his office in a small red brick building joining the old gray barracks now occupied by the officers and their families.

The drawing opposite shows some parts of this picturesque barrack as it is to-day, with bits of its unique life.

The children still play with the regimental dogs as they did in days of old, and here Mrs. Ewing used to come to sit under the great old willows, whence she could get those lovely glimpses of the blue river beyond.

It was in this very yard that she saw the pet bear of the regiment eating his dinner, while his favorite dog sat by and "licked his nose every time it came up from the bucket," as she writes in one of her home letters.

Here one may see, as in her day, the various scenes of a military life, — a red-coated British soldier, standing "at ease" under the old gallery by the worn stairs with his black cat friend peeping through the rails, or running a lawn-mower over the well-kept tennis green.

THE OLD BARRACKS

ON GUARD.

It was in these barracks that she found and rescued a black retriever from death, he having been shut up and basely deserted by the outgoing regiment. She named him Trouvè, and it is his likeness she has drawn in her story of "Benjy in Beastland," as Nox. There is a descendant of Black Trouvè's at the barracks to-day, — the children's pet and playfellow. Poor Trouvè had such an appetite that he was never satisfied, and was always stealing the meat for dinner; and his mistress had often to send and borrow of some kind neighbor, "as company was expected and Trouvè had eaten the joint!"

It was in these barracks that she found and rescued a black retriever from death, he having been shut up and basely deserted by the outgoing regiment. She named him Trouvè, and it is his likeness she has drawn in her story of "Benjy in Beastland," as Nox. There is a descendant of Black Trouvè's at the barracks to-day, — the children's pet and playfellow. Poor Trouvè had such an appetite that he was never satisfied, and was always stealing the meat for dinner; and his mistress had often to send and borrow of some kind neighbor, "as company was expected and Trouvè had eaten the joint!"

His mistress's fondness for all animals is shown throughout her writings. In reading that delicious bit of bush-life depicted by Father and Mother Hedgehog in the tale of "Father Hedgehog and his Neighbors," one can see how truly the author saw under prickly coats of quills the true instincts of animal life.

Dogs were her special favorites, and nothing was too good for them to eat, and no place too clean to be climbed on by their muddy paws She was always most tender of hurting their feelings, while many a stray pussy has found a comfortable home with her.

She did not care to cage a bird, for she loved them too deeply, — as she has shown in her "Idyll of a Wood."

Her dear dogs were her intimate friends, and once when she was calling at the house of a friend, where the vestibule had been newly scrubbed scrupulously clean, she was asked by her hostess to leave her dog, whose feet and coat were very muddy, out on the steps. She did so, but was compelled to go out several times during her visit, and whisper words of apology and condolence in the ear of her big banished pet, for fear he might be hurt in his doggish mind — at being left outside.

Here is another instance of her tender, droll ways with her dog friends.

A visitor calling at her house one day found her deep in writing, every chair and table being full of papers and books, so that there was no room for the tea-tray when the servant brought it in. Mrs. Ewing, looking up, said, "Oh, put it on the floor." So down it went. Now one of the dog friends (a great fellow) was present, and of course was curious to sniff the contents of the tray. The visitor was horrified at seeing his great muzzle nosing over the things, and exclaimed about it. Down on the floor beside him went his tender mistress, and with both arms about his neck she whispered to him not to mind that "horrid person's" insinuations and suspicions, but to watch her, that when she went she did not "carry away the silver spoons with her!" Wherever she went her dear dogs went with her, and whenever she speaks of animal life in her books, she shows her deep interest in their welfare, and insight into their habits.

MRS. EWING AND HECTOR.

CHAPTER IV.

of her friends remember Mrs. Ewing's keen appreciation of anything humorous, and the ready names, both apt and droll, but always quite inoffensive, that she applied to people and things as her vivid imagination suggested.

of her friends remember Mrs. Ewing's keen appreciation of anything humorous, and the ready names, both apt and droll, but always quite inoffensive, that she applied to people and things as her vivid imagination suggested.

Even in the choir of the Cathedral, where she always wished to be most reverent, her sense of the ridiculous sometimes overcame her, and she would have to smile almost audibly at some little incident insignificant in itself.

Across from where she sat in the choir of the church, she could see the verger blowing the bellows of the great organ, and as his stooping figure bent over, the long handle of the bellows stuck out from under the drooping fold of his black robe, giving the droll appearance of a tail! This was always, to her imagination, a most comical sight, and more than once she smiled at her friend on the seat opposite, quite upsetting that quiet lady's dignity.

One little lady in the choir, who always slid and glided into her seat with an undulating movement, never allowing her garments to touch anything as she went, was called by her, "Patha Furtiva," which is the Hebrew for a "thing which glides." Another's voice she always spoke of as "weepingly pitched " — which perfectly described it!

There was a family of unruly children living near her, by whose actions she was always much entertained. Doubtless some of the rather naughty — but oh, so natural! — boys and girls in some of her stories are drawn from these very children's characters.

On one occasion, when she was calling on their mother, sitting in the parlor, they noticed a rustling or scrambling in the great fireplace, behind the old fashioned fire-board. Presently down came this board flat, with a puff of dust, disclosing all the children in a bunch, with sooty faces and garments, sitting in the fireplace! They had hidden there, but, quarrelling, had pushed the board down.

MRS. EWING'S SEAT IN CHOIR OF CATHEDRAL.

Mrs. Ewing was interested in a story, then coming out in "Aunt Judy's Magazine," called "The Scaramouches," and she then and there bestowed upon these "mischief makers" the appropriate title of Scaramouches, by which they were always known thereafter.

She was interested in all the customs of this quaint colonial town, and of the Canadian winter dress she speaks in the story of "Three Christmas-Trees," where a boy is described as wearing "a hooded Indian winter coat of blue and scarlet," which is the picturesque Canadian blanket coat of winter. In that story she speaks also of the dry cold snow, so strange and wonderful to her English eyes, telling how, when the boys tried to make a real live snow-man, "the snow would not stick anywhere except on his shoulders," showing the extreme dryness and powdery lightness for which our Canadian snow is noted.

In this story there is an account of the life in this little town of her day, which tells of a custom still kept up by the Governor of the Province, of giving the children a Christmas-tree, or a party some time through the winter. Christmas-trees were then by no means so universal, even in England, as they now are, and in this little colonial town they were unknown, unknown, that is, till the Governor's wife gave her great children's party.

"The Governor had given a great many parties in his time. He had entertained big wigs and little wigs, the passing military and the local grandees. Everybody who had the remotest claim to attention had been attended to: the ladies had had their full share of balls and pleasure parties: only one class of the population had any complaint to prefer against his hospitality; but the class was a large one — it was the children. However, he was a bachelor, and knew next to nothing about little boys and girls: let us pity rather than blame him. At last he took to himself a wife; and among the many advantages of this important step was a due recognition of the claims of these young citizens. It was towards happy Christmas-tide that 'the Governor's amiable and admired lady' (as she was styled in the local newspaper) sent invitations for the first children's party. At the top of the note-paper was a very red robin, who carried a blue Christmas greeting in his mouth, and at the bottom — written with the A. D. C.'s best flourish — were the magic words, A Christmas-Tree. In spite of the flourishes — partly, perhaps, because of them — the A. D. C.'s handwriting, though handsome, was rather illegible. But for all this, most of the children invited contrived to read these words, and those who could not do so were not slow to learn the news by hearsay. There was to be a Christmas-tree! It would be like a birthday party, with this above ordinary birthdays, that there were to be presents for every one.

OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE, FREDERICTON.

"One of the children invited lived in a little white house, with a spruce fir-tree before the door. The spruce fir did this good service to the little house, that it helped people to find their way to it; and it was by no means easy for a stranger to find his way to any given house in this little town, especially if the house was small and white, and stood in one of the back streets. For most of the houses were small, and most of them were painted white, and the back streets ran parallel with each other, and had no names, and were all so much alike that it was very confusing-. For instance, if you had asked the way to Mr. So-and-So's, it is very probable that some friend would have directed you as follows: 'Go straight forward and take the first turning to your left, and you will find that there are four streets, which run at right angles to the one you are in and parallel with each other. Each of them has got a big pine in it — one of the old forest trees. Take the last street but one, and the fifth white house you come to is Mr. So-and-So's. He has green blinds and a colored servant.' You would not always have got such clear directions as these, but with them you would probably have found the house at last, partly by accident, partly by the blinds and colored servant. Some of the neighbors affirmed that the little white house had a name; that all the houses and streets had names, only they were traditional and not recorded any where; that very few people knew them, and nobody made any use of them. The name of the little white house was said to be Trafalgar Villa, which seemed so inappropriate to the modest peaceful little home, that the man who lived in it tried to find out why it had been so called. He thought that his predecessor must have been in the navy, until he found that he had been the owner of what is called a 'dry-goods store,' which seems to mean a shop where things are sold which are not good to eat or drink — such as drapery. At last somebody said, that as there was a public-house called 'The Duke of Wellington' at the corner of the street, there probably had been a nearer one called 'The Nelson,' which had been burnt down, and that the man who built 'The Nelson' had built the house With a spruce fir before it, and that so the name had arisen, — an explanation which was just so far probable, that public-houses and fires were of frequent occurrence in those parts."

This was the way it was when she was living here. How fond she was of the beautiful woods, and of always searching for, and finding the smallest thing, seeing the fulness of God's great love in all, and so, keenly appreciating it.

This was the way it was when she was living here. How fond she was of the beautiful woods, and of always searching for, and finding the smallest thing, seeing the fulness of God's great love in all, and so, keenly appreciating it.

See how in her "Idyll of the Wood" she makes the wise old man say: "Well, well, my children, to know and love a wood truly, it may be that one must live in it as I have done; and then a lifetime will scarcely reveal all its beauties or exhaust its lessons; but even then one must have eyes that see, and ears that hear, or one misses a good deal," — speaking all through this delightsome Idyll as only one who knows and sees the "woods" root and branch can speak of its glories. I seem to feel her very presence in those woods to-day, and love to fancy her eager face peering among the waving ferns for the hidden treasures, and looking up through the thick, waving branches laced into a canopy overhead, now in deep shade and now flecked over with the peeping sunshine.

CHAPTER V.

housekeepers in this community still smile over the recollections of many amusing scenes in the household of these two literary, musical, military people, both so absorbed in their special work, making use of the smallest amount of furniture possible, and allowing the household to "run itself," as the saying is. Funny times and droll mistakes are recalled, such as the stopping of a stove-pipe hole in the chimney with a bath sponge, causing a long search for this article, and a smoking flue in consequence of the stopped draught, windows being left wide to let in winter breezes and do away with the smoke, while the occupant of the room sat wrapped up and complained of the cold!

housekeepers in this community still smile over the recollections of many amusing scenes in the household of these two literary, musical, military people, both so absorbed in their special work, making use of the smallest amount of furniture possible, and allowing the household to "run itself," as the saying is. Funny times and droll mistakes are recalled, such as the stopping of a stove-pipe hole in the chimney with a bath sponge, causing a long search for this article, and a smoking flue in consequence of the stopped draught, windows being left wide to let in winter breezes and do away with the smoke, while the occupant of the room sat wrapped up and complained of the cold!

Many a morning, early, the pair used to go over to Bishopscote and beg to be asked to breakfast, as that meal had not been provided for in their household.

However, with the most, at times, untidy aspect of rooms, it was always a very attractive place to visit, and many loved to go to this home with its nameless charm of literary disorder, always some pretty decorations, and here and there Mrs. Ewing's own sketches pinned on the walls.

Ah, it was the gentle manner of the beautiful hostess, — that inborn grace of spirit which in a short conversation would cause the most critical housekeeper to entirely forget the surroundings, and to rejoice in that sweet society! A visitor would perhaps find her hostess seated on the hearth-rug, her papers on her lap, feet outstretched, writing away to get her manuscript complete for the story that was to go by the English mail, an orderly standing the while, like a wooden sentinel, waiting to take the packet when it should be ready.

Waving her pen hospitably, and going straight on with her work, she would invite the friend to enter — to excuse the disorder and lack of chairs (all occupied by piles of manuscript), suggesting that if the caller really wished to help her, she could do so by gathering up the various piles in the order of their numbering, and bring them to her to tie up.

WINDOW IN "REKA DOM."

At one time this little mistress, so absorbed in her great work that all else seemed of minor importance (for which we ought to be truly thankful), determined to give a dinner party in return for the many invitations and hospitalities that she had received. So many obstacles, in the way of lack of proper dishes and the necessary accoutrements for such an affair, in her limited military establishment, arose, that they would have daunted many a housewife, — but not our little lady of the "great heart." Her ready wit supplied the lack, and her own generous and liberal mind made her believe that others were the same; so she sent out and borrowed all the necessary articles, including glass, china, and silver candlesticks, from her neighbors and friends.

Her rooms were crowded, and it was a most brilliant affair — where the people, with appreciation of her entertainment, noticed but little the lack of things which usually go to make up the substance of social affairs. As the last guests were leaving, however, there was a great uproar heard from the basement kitchen regions of the house, which became so pronounced that Mrs. Ewing asked her husband to descend and inquire into the cause thereof, as she feared the orderly and the borrowed butler were quarrelling. He found this indeed the case, as the two were having a stand-up fight amid the wreck of many borrowed articles of glass, dropped in his heat by the butler, on the kitchen floor, while the cook was prone upon the hearth in a semi-intoxicated state, and literally a "heap of smoking ruins" (as Mrs. Ewing expressed it), having put a lighted pipe into her pocket

Her merriment over this amusing incident was (as always) most infectious, and what to some would have been a trial and almost a disgrace, was turned into an amusing episode, looked at with her full appreciation of its humorous aspect.

Her absorption in anything which gave her an idea for a story was really wonderful, and showed how her active mind was always in its beloved work.

Once when she was calling at Bishopscote, the English mail, arriving then only once or twice a month, came, bringing to the Bishop a new book of interesting travel and research in the Arctic Seas. She seized upon the volume and sat down to devour its contents, which suggested a new theme to her. When it came time to leave she refused to be torn away from her treasure trove, and begged hard to be invited to "stay to tea," that she might finish the book. But this not being at all possible in the Bishop's household that special evening, she was compelled to part with it, and going home, at once wrote out the story it inspired, which afterward developed into that charming tale of Kerguslen's Land, with such a charming description of the home of the mysterious albatross, and the fascinating conversations carried on between Father and Mother Albatross, over their nest of little ones, about the cast-away man, — Father Albatross discoursing about him in this fashion, in superior contempt: —

"They are very curious creatures" (he says to Mother A.). "The fancy they have for wandering about between sea and sky when nature has not enabled them to support themselves in either, is truly wonderful!"

The whole dialogue is most delightful, showing her marvellous insight throughout this, as in all her other wonderful animal stories, both of birds and furry folk. She would forget all else in reading a book, and become wrapped in a dream of reproducing an idea suggested by some subject in it. How keenly she saw from a child's eyes, and with a child's mind its outlook on life, is shown by the "real child" language in those stories where the child hero or heroine are made to, as it were, tell the story themselves; "Mary's Meadow" and "Flat-Iron for a Farthing" being especially good examples of this wonderful power of hers, of being able to see from all points.

Here is another sweet recollection: While Mrs. Ewing was living here, a little lad was very ill, and kept within doors all winter. Our tender little lady used to go every evening, towards dusk ("story time"), and tell to him the most beautiful stories by firelight.

MRS. EWING TELLING STORIES TO THE CHILDREN.

This "story-telling" was a great gift of hers, as her sister relates in her account of her childhood. And the stories were so wonderful, and, told in her own sweet manner, so irresistible, that a group of grown folks usually crowded about the door of the room where she was "telling a story" to that favored little boy!

Her lessons to her class in Sunday School were made so attractive that the class next to hers had hard work not to neglect their own lessons and teacher in listening to her most interesting way of putting things.

CHAPTER VI.

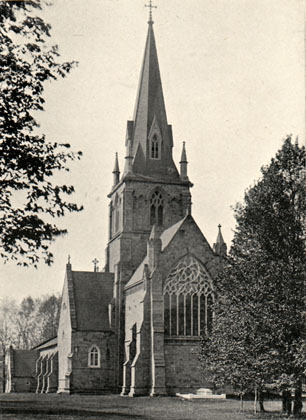

Cathedral of Fredericton was a great source of comfort and pleasure to Mrs. Ewing, who was always devoted to her church, and did not expect to find so beautiful a specimen architecturally of an English church in our Canadian land.

Cathedral of Fredericton was a great source of comfort and pleasure to Mrs. Ewing, who was always devoted to her church, and did not expect to find so beautiful a specimen architecturally of an English church in our Canadian land.

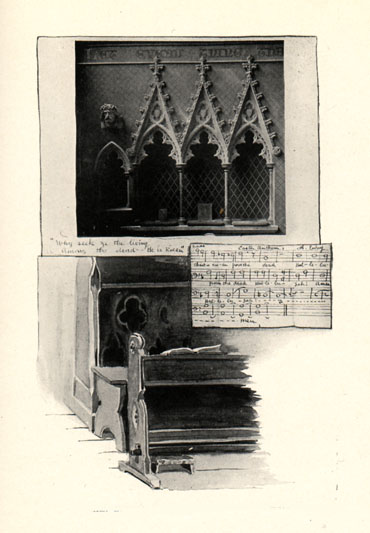

Her husband was organist in this choir during their stay, and wrote many beautiful musical compositions during his lifetime, perhaps the best known being that grand hymn "Jerusalem the Golden," which has sometimes been wrongly attributed to his uncle, Bishop Ewing. 2 He also conducted the Choral Society, of which she speaks in her letters. How dearly she loved to sit in her seat in that choir, listening to the inspired tones from her beloved husband's hands, under her revered Bishop, and opposite to her friend his wife!

Sometimes to-day, when one sees this latter gentle lady sitting in her accustomed place in the choir, one can fancy that the scene before her fades away, leaving but the two faces she loved so well, — that of "her dear Lord" in his Bishop's seat, and of the sweet singer opposite to her. For, as this singer herself says, in "The Story of a Short Life," "Can the last parting do much to hurt such friendships between good souls, who have so long learnt to say farewell; to love in absence, to trust through silence, and to have faith in reunion?" Surely, blessed are such reunions!

In this seat in the choir did our little lady love to sit, much enjoying always the beauty of the Cathedral with its many rich parts, each having its own special meaning in ornament, in window, and in the very shape of the building itself, all bearing witness to the deep thought and reverent care bestowed upon its structure by him who was its first Bishop, who for so many years devoted his life to its erection. The rich chime of bells, and much of the ornamentation, were brought over by his efforts from England, and in the shadow of its beautiful spire his body rests to-day, close under its gray walls, which are a fitting memorial to his love and zeal for his church and its people.

CATHEDRAL OF FREDERICTON.

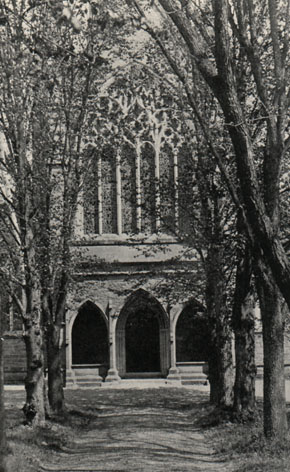

There she must often have watched, as we can to-day, the red coats of the officers as they filed up the centre aisle of the church, with much clanking of swords and ringing of spurred heels. And out of the beautiful Eastern Door she has looked in loving admiration, seeing through its stone Gothic curves, in the soft light of a summer evening, the arches of the graceful branching trees over the path beyond. As I sketched this seat of hers, the verger handed me an anthem composed by Major Ewing, with this, to me at that time, singularly meaning-full title, "Why seek ye the living among the dead?" which seemed so to fit her own hopeful views of death.

In many of Mrs. Ewing's clever sketches about Fredericton the old gray willows appear. She used to form merry parties of sketchers, herself always ready to help and offer assistance to unaccustomed hands.

The spire of her beloved Cathedral is also often seen, taken from all points of view; and much of her time was spent within the hospitable, vine-covered walls of Bishopscote, — of which we have a little picture, with a glimpse of its gentle minister's wife in the doorway, to whose aid we owe so many of these recollections.

Here she always made herself quite at home, — running in and out at all times, finding in the Bishop's wife a loving friend and admonisher, though the latter must often have been sorely tried by our little lady's caprices and unpractical experiments.

Like a child, her bright, joyous nature seized upon any novel experience with pleasure, and any play was entered into with zest.

Once in the attic she discovered an old set of battledore and shuttlecock, and soon had every one in a merry game. And to-day, there may be seen, in testimony of her eager play, a broken battledore belonging to the old set!

EASTERN DOOR OF THE CATHEDRAL.

BISHOPSCOTE.

Her love of doing everything, whether she understood the mechanical part of it or not, was shown once when she came to Bishopscote, and, finding every one busily engaged on some work for church decoration, she determined to work with them, and insisted that she should be allowed to do so. Thereupon she proceeded to cut out the letters for an illuminated text, — from the only paper obtainable for it, — but cut them every one out on the wrong side of the paper, so that upon turning them all were backward! She crushed them up in her hands and declared all would be right, for she would send to England for more paper; but upon being told how impossible this would be, as the work had to be ready for the morrow, her contrition was great! Down upon her knees she went, with her hands in a prayerful attitude before her, and, supplicating them all to forgive her for her naughtiness, drove away the cloud caused by her mischievousness, with her droll merry manners, as was always her way of doing, from a child.

Her love of fun was so irresistible, her repentance for wrong-doing so great, the sternest heart could not hold anything against her. Many a scrape has she got her beloved doggies out of, by her manner of turning away the wrath of their accusers; for the love she bore these dogs, great and small, was wonderful.

CHAPTER VII.

of the town there is a range of low hills, and on that part of it to which the University of New Brunswick has given the name of College Road, she used to walk and enjoy its Canadian aspect. It was from that point many of her lovely sketches in color were painted. Here, also, in the winter, she and her husband, with their dear friends the Misses R— and others, used to walk on snow-shoes, and sit under shelters made of fir boughs, going over their Hebrew study together, or singing with their keen love for music. The Ewings greatly enjoyed the "musical evenings" (of which she speaks in one of the letters printed here) spent with these friends while in Fredericton.

of the town there is a range of low hills, and on that part of it to which the University of New Brunswick has given the name of College Road, she used to walk and enjoy its Canadian aspect. It was from that point many of her lovely sketches in color were painted. Here, also, in the winter, she and her husband, with their dear friends the Misses R— and others, used to walk on snow-shoes, and sit under shelters made of fir boughs, going over their Hebrew study together, or singing with their keen love for music. The Ewings greatly enjoyed the "musical evenings" (of which she speaks in one of the letters printed here) spent with these friends while in Fredericton.

In her walks over these hills, and in the gardens of the town, she found many new flower friends.

The Trillium she first saw here, and it was a great joy to her, with its beauty and grace. After returning to England she had some seeds of this plant sent out to her, and tried to grow it there, and it inspired her to write the beautiful legend of "The Trinity Flower," in which she immortalizes this pure blossom of our wilds, thus describing its beauty: "Every part was threefold. The leaves were three, the petals three, the sepals three. The flower was snow white, but on each of the three parts it was shaded with crimson stripes, like white garments dyed in blood."

The Lily of the Valley was another special favorite of hers, and inspired the graceful legend which she wrote, wherein she calls the plant "Ladders to Heaven," saying, "It hath a rare and delicate perfume, and having many white bells on many footstalks up the stem, one above the other, as the angels stood in Jacob's dream, the common children call it 'Ladders to Heaven."'

She found so many new wild flowers, that she made an extensive collection, of which she speaks in one letter, and I am told that she also added the Mellicite Indian names to her specimens, through the aid of her Indian "brother" of whom she speaks, Peter Poultice, who came from his encampment (there to-day) just across the river to visit his interested friends, the pale faces from over the great ocean, and to sell them bead work and moccasons, as is the custom of the red brother here always.

FIR BOUGH SHELTER.

MRS. EWING'S BARN AND CANOE.

They had a canoe from him, and Mrs. Ewing was remarkably fearless in this frail craft for one so unaccustomed to such venturous boating. The temptations to her, of the many beautiful views on and about this great broad river St. John, and of being able with a canoe to enter the lovely little streams which flow into it, made her enjoy it keenly.

I can fancy her delight in the great beauty of those two streams, the Nash-waak, and the Nash-wa-sis (or little Nashwaak), known to every canoe lover in these parts.

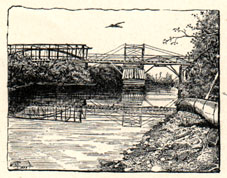

THE OLD NASHWAAK BRIDGE.

This picturesque bridge is the entrance to that lovely little stream the Nashwaak, which she describes in her letter that tells of their picnics in canoes. It was evidently then as it is now, except that the graceful bridge has been replaced by a hideous structure, which I am glad her artist eye did not have to see in those days. And to-day the sawdust from the great ruthless mill at the head of the stream is fast filling up and spoiling the beautiful wavy stream, narrowing it even to the exclusion of canoes.

CHAPTER VIII.

great fondness for flowers is seen all through her writings, and her "Letters from a Little Garden" shows her practical experience in flower growing and tending. In her books she gives good advice to other flower lovers, quoting from Charles Dudley Warner's "My Summer in a Garden," with a full appreciation of its delicious humor.

great fondness for flowers is seen all through her writings, and her "Letters from a Little Garden" shows her practical experience in flower growing and tending. In her books she gives good advice to other flower lovers, quoting from Charles Dudley Warner's "My Summer in a Garden," with a full appreciation of its delicious humor.

In her verses and maxims for use in gardening ("Garden Lore"), two trite maxims bespeak the thorough sympathy she had for plants and plant growers. She says, in this "Garden Lore," "Cut a rose for your neighbor, and it will tell two buds to blossom for you;" and again: "Enough comes out of anybody's old garden in autumn to stock a new one for somebody else. But you want sympathy on one side, and sense on the other, and they are rarer than most perennials!"

How sorely tried such a lover of plants and "little gardens" must have been in her life as an officer's wife, sent from post to post, at having to break up her homes, leaving many little gardens just started!

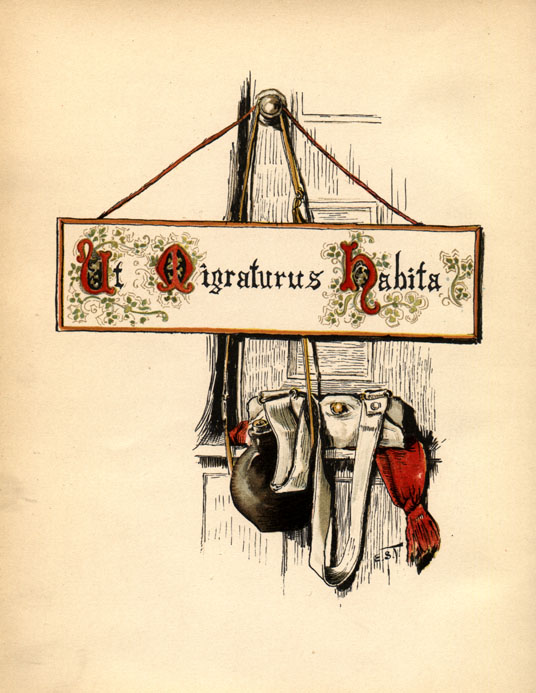

How tenderly, in the letter written from Aldershot Camp back to Fredericton, shortly after she returned to England, does she speak of her house plants there, and the care she takes of them! She was very fond of the dear old English custom of having house mottoes; and the one reproduced in the front of this book she had painted and framed, to hang on the wall of each new home:—

"Ut migraturus, habita."

"Dwell as if about to depart!"

Another favorite one of her many house mottoes is this cleverly arranged Latin one, curtailing one word into four meanings:

"Amore, more, ore, re."

"By love, by manners, by word, by action!"

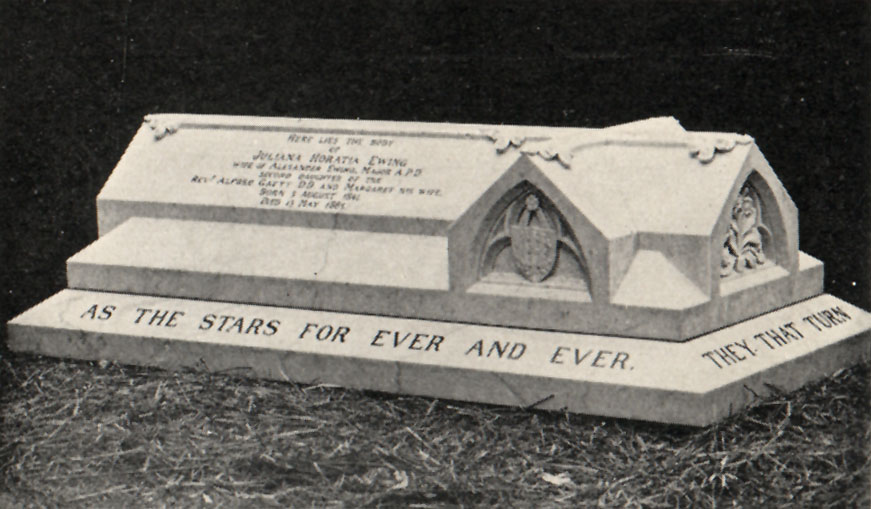

Things with meanings rejoiced her heart, and her own sweet namesake flower, the Chinese Primrose, which is about her portrait here, was a favorite with her; and it seems to make the little primrose as familiar to us as a choice potted plant, dearer and nearer, to know of its association with her. A spray of this flower is carved upon her quiet tomb at Trull.

This letter was written shortly after her return to England.

Mrs. Ewing's Letter.

25 Feb., 1870.

X LINES S. CAMP, ALDERSHOT.

MY DEAR B—: We were delighted to get yours (and M.'s) long letters. We have many kind correspondents in Fredericton, and all the news interests us. You have had a wonderful winter. Here we have had a little — so cold — that frozen sponges, cruelly killed plants, and cutting winds piercing our wooden walls, quite recalled New Brunswick! ... I used to take my poor plants into my bedroom at night, and cover them up — but all in vain; they were frozen as completely as in D— J—'s "old barn!"

But oh! I do revel in the spring days we get now from time to time. I long to see primroses — and I have not seen a daisy for three years. How I hope they won't send us away first to "furrin" parts! We still know nothing about our future. We have many charming friends here, and are very comfortable. Mr. Ewing has a very nice organ to play upon at "All Saints'" near here. We often go there on Sunday, for he plays very often at the services, and there is also a Wednesday evening service at which he always plays. But we have very few week-day services, and miss the daily prayer at the Cathedral very much indeed. If at our next station we have more "church privileges," it will go far to reconcile me to the move. I hope to go home before we settle again. Indeed, we have promised my mother to do so if all be well....

We had an evening party the other night in our tiny habitation! We turned out of our bedroom (which opens into the drawing-room), and I made a pretty little coffee-room of it. All went off very well, but it seems dreary work to me to have a commonplace evening when we have been used to musical ones! I fear we could not get one up here. And then the rooms are too small. The dining-room is so narrow that we could only sit on one side of the supper table...

At the beginning of this month I was very busy composing valentines for my sisters, etc., etc., and Rex insisted on having one, so I had to make one for him, of which Trouvè was the subject! That dear old boy is very well, and in fine condition. We have another dog also living with us, and they are great friends. Trouvè sleeps with us, and the other sleeps with my maid.

Do you know whether the S—s are still in Fredericton? I have often wondered what became of them in the giving up of the barracks. They are very unpractical — poor souls — and I would like to hear if they were doing well or ill. Can you find out for me, my dear?

We are very glad to hear how the Choral S. holds on. The other day, we and some friends of ours went to the Crystal Palace, and heard Mendelssohn's (Lobgesang). We did enjoy it! One verse of the choral was sung in unison by all voices (about two hundred and fifty or more). Imagine the effect! My husband's love and mine. Trouvè's respects to Thistle.

Yours, dear B—, very affectionately,

JULIANA HORATIA EWING.

How like her own dear self is this rare plant, coming from a far-away land, but familiarizing itself to us so sweetly in an every-day life, until now it is a household favorite! It is not hard to understand the deep hold she obtained on the hearts of her Canadian friends, in the all too short years she spent with us, on this continent. And now, comes a budget of her own brilliant letters which we are indeed fortunate in securing, full of a sweet personality and gayety — in whose glowing pages we can see more clearly into the character and life of our dear friend than in any other way now possible to us. They are indeed a rich treat, and cannot fail to reawaken our love for her, and to help towards keeping that sweet memory "green" in our hearts. In fact, the sketches and letters taken together seem to be an autobiography almost, written and illustrated by herself, of her life with us.

MAJOR AND MRS. EWING AND HECTOR.

MRS. EWING'S LETTERS

AND

FAC-SIMILES OF HER WATER-COLOR SKETCHES

MADE WHILE IN FREDERICTON.

Mrs. Ewing's Letters.

FREDERICTON, NEW BRUNSWICK,

July, 1867.

MY DEAR MRS. EWING, — ... Since we must be "abroad" somewhere, I do not think we could well have been more fortunate in a station than we are in being sent here. There is that most disagreeable Atlantic between us and Great Britain, but otherwise it is in many respects very like home. We hear rather appalling accounts of the winter, but we were told awful things of the summer heats; and yet (except for occasional oppressive days) we have found it delightful. It is rather blazing in the morning often, and makes one rather giddy if one attempts to walk much; but the evenings and nights are delicious, and quite cool. Fredericton is on the river, and all by the river side it is lovely, and we have not yet been able to decide by what lights and at what time of day it looks most beautiful. Very fine willows grow on the bank, and the fireflies float about under them like falling stars. The moonlight and starlight nights are splendid, and the skies are particularly beautiful. We were detained for some days both at Halifax and at S. John; but we are very glad that our lot has fallen here rather than in either of those places. Halifax has lovely country near it, but S. John is a town pure and simple; and I think if one must live in a town one likes it to be as highly civilized a city as possible. S. John is more like a watering place without the shore. I suppose the New Brunswickers would be duly indignant at my not calling Fredericton a town, for it is a CITY! but it is all in lovely country, the streets are planted with trees, and have no names, and there are very few lamps; most of them are like shady lanes, with pretty wooden houses with (generally) very pretty faces at the windows! For another attraction which this place possesses is the beauty of the women, both of the upper and lower classes. Not that we have seen any one very beautiful woman (such as one sometimes sees at home) but that, almost every girl you meet is very pretty, and very gentle and sweet looking. The young ladies have particularly pleasant, unaffected manners, too....

The ferns, flowers, mosses, and lichens in the woods about here are most beautiful, and it is an utterly new pleasure to me to find so many plants I have never seen. In fact, the botany of these parts seems richly luxuriant, and to have been very little investigated. I have dried a few things in my blotting-books, etc., but we have no apparatus with us. However, we have ordered two boards at the carpenter's for a press, and when we have out a box from England we shall have some proper paper and portfolio sent — and I hope we shall be able to bring home some specimens of the beautiful things out here. For want of proper means to preserve those we first got, I have been making rough coloured sketches of them in a note-book of Alexander's which we have devoted to the purpose; and whenever we meet anybody who seems likely to be knowing on the subject, we ask the names of the flowers. Some have exquisite perfumes, which, unhappily, one can neither figure nor preserve! One almost wonders that more plants from this country are not cultivated in England, as whatever can stand these winters would well live with us. We have just heard of some wonderful orchids in a bog two or three miles away, and I am greatly impatient to get at them, for vegetation is so rapid here, — the flowers are out and then gone in a day or two....

I am sending you a small sketch of our house, and also one from a hasty sketch I made in my note-book as we came up the river into Fredericton. It was, in fact, our first view of our new home.... You cannot think how lovely it is coming up the river from S. John to this place. The colouring is so exquisite, the sky and clouds are so beautiful, the pine woods look at times the richest purple in the distance; and the foliage of the white birches, and brushwood, and grass near the shore, was of most vivid pale greens when we came up. I suppose in autumn, when the maple trees turn scarlet, it will be lovelier still. People say that whatever you may have heard or read about American woods in autumn, nothing but seeing them can give you an idea of the wonderful brilliancy of their colours....

I must tell you about our house. You will, I think, be amused at its palatial appearance; it is much larger than necessary, though Rex justly says I always give it a more magnificent appearance on paper than it really possesses. It has, however, twenty-one rooms in it!! though they are not very large ones. He could keep an hotel — or invite my seven brothers and sisters to visit me. We talk of giving Trot (the dog) a bedroom, sitting-room (and he might have a dressing-room!) to himself when he arrives. Don't think us quite mad! We had much humbler intentions, but it fell out thus: When we arrived we were told we should have to wait a long time for a house, as none were vacant; of course it was desirable to get one as soon as possible. The second day, Rex discovered this one, which was in a fearful state of disrepair, but was being put in order by the landlord; he took it, and we are only furnishing just what we want. It has many great advantages. It is in the best situation we could have chosen, there is a well of good water, we have very nice neighbours, and we are close to the Cathedral. We are not overlooked, and have a lovely lookout over the river, with a ferryboat just opposite to our front door. There is ample space for a good garden, and our landlord is building us a huge sort of barn, which I fancy is to embrace coach-house, stables etc., and which (as we possess no equipage) I think will have to be devoted to the PIG we purpose to keep; he will consequently have as much spare space as ourselves! Fancy Alexander coming in yesterday and announcing to me his intention (please the pigs!) of fattening a porker for Christmas!! An officer has told him that a young pig may be bought for half a dollar, and live on the household refuse till Christmas, and then either be killed or sold. As we neither of us like pork, I think our "little pig will go to market!" Most opportunely in turning out his (very untidy) drawers yesterday he found a half dollar which had been there since he was in China, so we may look upon the pig as purchased — so to speak.

August 1st, 1867. "Reka Dom,"

FREDERICTON, N. B.

MY DEAREST FATHER, — I am going to write to you this time.... We have had some very rainy weather, and some intensely hot (even Rex allowing that it was overpowering and like China). To-day, a cloudless sky and brilliant sun, but a refreshing breeze; and what breeze is to be got, we get, — living by the river. Did I tell mother of that beautiful thunder-storm we saw just before leaving our last hotel? The sky had been of such a blue as I never saw, — a pure, intense, opaque, speedwell colour. It seems a poor comparison, but it reminded me of the blue which they use on church or cathedral roofs with golden stars, and which is usually deeper and more intense than the sky which it represents. On this were wonderful cumulus clouds of splendid tints. One grand mass standing off in awfully powerful relief, against a golden glow, reminded us of Sinai, when the mount burned with fire, and one expected to see the tables of the law appear. These mountainous masses faded after sunset, and then two other currents of very electrical appearance touched each other, and till dark we watched them emitting the loveliest lightning I ever saw. The sheet lightning was incessant, and the forked ran among it and cleft the clouds in the most lovely way. They had a ludicrous resemblance to two gigantic and wonderful firestones perpetually rubbed together. Rex fetched me to see this storm from the other side of the house, where I was frantically splashing paint on to paper, trying to catch the sunset sky, against which stood off one of the houses they build here for the swallows....

Last Thursday we went to dine at Government House, the first time, — about twenty-two people, — and as we were in the very worst of our difficulties a capital dinner was an absolute treat! The general introduced me to the Bishop, and he took me in to dinner. I enjoyed it immensely, for he is very clever and awfully amusing, and told me the funniest anecdotes. He has been away until now, but next day he and Mrs. Medley called on us, and we like them both extremely. Mrs. Medley told us some clergyman has been raving in their house about mother's writings, and had said that whole pieces were taken out of Aunt Judy's Magazine into American newspapers, sometimes without an acknowledgment. When he went away, the Bishop looked at me in his point-blank way and said, very kindly, after his rather awkward fashion, "If you would like to see Maryland Church, I will drive you there, — not to-morrow, Saturday is a busy day with me, but next week." Is n't it kind? So I expect we shall probably get to see some of the country in very good company. Yesterday he preached both A. M. and P. M., and I really doubt if any of our English swells beat him, on the whole. The learning, the logic, the irrepressible irony at times, the intense simplicity, and the exquisite touches of pathos, I hardly think Oxon, Vaughan, Eber, or anybody could excel. He preached A. M. on the "whole creation groaning," etc., and brought out a forcible and (to me) new idea, — that if we had been alive in any of the periods of great "disturbance" of the physical world (the glacial or volcanic, etc.), our faith would probably have failed to foresee the physical beauty and order that would come out of it all: the rocks on the sunny hillside, the waters in their own places, the flowers, etc., etc.; and that, although the divisions of the Church of Christ, the distractions and confusions and inconsistencies which make Christianity seem almost useless, the darkness of dispensations and all the disturbance of the moral world, make one inclined to give up hope, we were to draw comfort from creation. He had been charmingly sarcastic in the hastiness and almost invariable erroneousness of man's very self-satisfied judgment of providence in all times; but there was a sort of grave authority that was very impressive as he admonished us that since God had loved His lower creation so well as to bring such beautiful order out of such ghastly confusion, He would bring out of all the moral disorder and disturbance a new heaven and a new earth for those whom Jesus died to redeem. Towards the end he gave a practical turn, and speaking of the love of Christ, — "a love such as no earthly friend can feel for us, suffering as no earthly friend ever suffered for one, interceding as no earthly friend can plead, a Home at last such as no one who loves us can provide here, however they may wish and try." He uses very simple, forcible language, has a voice as soft as Vaughan's, and it is as clear as a bell. He hardly ever lifts his eyes, and uses no action whatever. His premises and deductions, his biting bits of sarcasm, and his touches of pathos go down the Cathedral without the slightest assistance from "delivery;" but they are just the reverse of the style of sermon which Goulburn calls "like the arrow shot at a venture that hit King Ahab," with the difference that they seldom hit anybody in particular. When he is most severe he looks so awfully innocent. P. M. he preached on Rizpah, the daughter of Aiah, and the execution of Saul's sons. It was cleverer than the other, — one of the ablest bits of Biblical criticism one ever heard. Rex said the composition seemed to him so perfect. It really is a wonderful piece of good fortune to be under him. He has been out here twenty-two years (or more, — I forget), and he turns up at the 7.30 A. M. daily services, and walks into the Cathedral with a pastoral staff much bigger than himself. Tell Regie I have got a "relic" for him which I will send him. It is a bit of lichen from the nameless grave of one of the first settlers here. In old Judge Parker's garden (a very pretty place, with a lovely peep of the river through trees, like an Italian lake), in a field, are the graves of the first settlers. On one are some rudely cut initials, the last being "B." It was really an affecting sight, amid the prosperity to which this lovely spot has attained. One imagines how beautiful it must have looked to their eyes as a spot to "settle" in. We have made out a great many both of the ferns and flowers, and we have a good many in press, and to-day I am going to try and get some paper to "fix" them in....

Ever, my dearest Father,

Your loving daughter,

J. H. EWING.

11TH SUNDAY AFTER TRINITY, 1867.

WE have the most charming room, with two windows looking east to the river; Rex says the view beats the Lake Hotel at Killarney! He wakes at unearthly hours, and lies wrapt in the enjoyment of using a telescope in bed!! He kept us awake from 3 A. M. the first morning, looking at the view, and indeed it was lovely, — the white mist rolling off the river, sunrise behind the pine woods and willows, and canoes coming down reminding one of Hiawatha's "Like a yellow leaf it floated." They do look just like autumn leaves floating on the water. I don't think Rex will exist long without one!...

Last Friday we were asked to Government House for a picnic.... We went across the river, and by water up the Nashwaak Cis. (i. e., Little Nashwaak), and landed at a very pretty spot, where we ate luncheon off such lovely old china I wonder his Excellency had the heart to risk it at a picnic! The A. D. C. lent Rex his own boat, that Rex might row me there. I told him I must have a good wrap and got a buffalo robe to keep me warm, and sat like a queen in the stern. There were lots of canoes and a few boats... Coming back down the Cis it was lovely, half dark, and the canoes gliding past among the shadows. The Cis was very narrow and required careful steering. I got some new water lilies. When we got into the big river again, the wind was very high, and it was nearly dark, and the waves were quite wonderful... the canoes found it tiresome work. There was a dance afterwards at Government House, but we left in good time, and walked home. About half-past one, I was roused by Rex asking if anything was the matter. I could hear nothing, but he exclaimed, "It's the fire-bell!" and jumped up like a shot.

[I must tell you that, the day the Medleys left, the Bishop told us that he had told his next-door neighbour where the church plate was, in case of a fire, and what he specially wished to be saved, adding that the man had looked at a long box and said: "Is this valuable?" "Very," said the Bishop, "What is it? Music?" on which, as the Bishop said he did not seem to see it, Rex said, "Well, if there's a fire, I must save the music."]

THE NASHWAAK.

Well, when I went into the bath-room and saw the blaze in the sky, it seemed to me to come from the Medleys, so I told Rex. "Then I must save the anthems!" he cried in a thunderous voice (it was almost amusing), and off he went. We could n't find matches, so he dressed in the dark, and in the dark I was left. I could hear the peculiar roar of the fire, and see the flames rising up through the open window. I got awfully lonely, so I awoke "Sarah" with much difficulty and got a light, and told her to make a fire and get tea ready for Rex when he returned, and went back to the window to watch. Time went on, the fire got larger, and no Rex returned. At last I got so nervous I wrapped up, left the house, took my maid with me, and went off to find the fire, — and Rex! When we got to the Cathedral and Bishopscote happily it was not there, so on we went. Fire is very delusive at night, and I may as well say it was in the position of the Bishop's palace, only about a quarter of a mile or more further up the town. As we got nearer we seemed to be going into the blaze of falling sparks, and at last we found it. We had passed the place an hour or so before! It was a square called Phoenix Square, and how many times it has risen from its own ashes I know not, but the other half of the square was burned down just before we came, and when Sarah and I reached the spot, not one stone was left upon another, or rather not one plank, for it was wood, of course. But a large building at the corner, — a brick house, offices, — which had held out sometime, was in full blaze. It was a wonderful sight. The flames poured out of the windows, and licked round the walls, reminding one of the fire that licked up the water in the trench round Elijah's sacrifice. Rex was with the other officers, keeping an eye on the fuel-yard which was near, and from which soldiers were employed in sweeping away the burning embers as they fell. It was most providential that the wind set over the river instead of over the city, otherwise, being a dry night, high wind, and the fire engines about as available as a boys squirt, probably two-thirds of the town would have gone. An almost comical element (as one did n't suffer one's self) was to see the spectators, who kept getting the falling sparks into their eyes, going about with pocket-handkerchiefs to their faces. Also a small boy who laid a complaint to Major Graham against the soldiers who were protecting the rescued property, because they would n't give him some small article that belonged to him. The disgusting part is that these fires are said to be almost always the work of incendiaries....

Your loving sister,

J. H. EWING.

17 August, 1867.

"REKA DOM." FREDERICTON.

MY DEAREST MOTHER, — ... Now I must tell you all our news. First about the Episcopal family. You know they have been away for five weeks, and we met them first at Government House. Since then they have certainly done their best to make up for lost time, in the way of kindness, and it is not the least of the many blessings of my home here to have such very kind people about one, as our neighbours in general are, and such unusually good, intellectual, and friendly friends as the Medleys. He was a friend of John Newman, and associated with him in working at the Lives of the Fathers, etc., and Newman's secession was a great grief to him. He is awfully fond of music, and composes chants, etc. He is a fluent Hebrew scholar, and is certainly, as I told you, one of the ablest preachers I ever heard. He has been very near to going home to the council that is to be held at Lambeth, only he could not make out that the subjects of discussion had been settled, so was not certain that it would come to much, and had confirmations here, and did not like to bring Mrs. Medley back in winter, for she is nearly as bad a sailor as I am, or you might have seen them, and heard of us. They are great admirers of yours. Especially they are devoted to the Parables. Mrs. Medley told me to-day they owe you so much, she was delighted to do anything for your daughter; so you see, dear mother, you have, so to speak, provided me a motherly friend in these distant parts. She is a great gardener and a botanist, and lithographs a little.... They are going away again on a Confirmation tour directly, but meanwhile we see them constantly; they ask us in perpetually to meals, and send us vegetables and flowers. I need hardly say that Rex and Episcopus himself are pretty inseparable at "the instrument," and that Rex is appointed supplementary organist, and has joined the choir. He is going to play at the anniversary festival next Sunday, and the choir generally are quite as much edified and charmed to see the author of "Jerusalem," and quite as much astonished to find (and still a little sceptical) that "Argyle and the Isles" was not the composer, as if we all were living in a small English watering place. This you would anticipate; but you would hardly expect to hear that the Bishop evolved and propounded to me the proposal, that if I would teach him German this winter, he would teach me Hebrew. He buys books evidently with an appetite, and will lend us any, so we are well off to an extent that seems marvellous and is truly delightful.

MY DEAREST MOTHER, — ... Now I must tell you all our news. First about the Episcopal family. You know they have been away for five weeks, and we met them first at Government House. Since then they have certainly done their best to make up for lost time, in the way of kindness, and it is not the least of the many blessings of my home here to have such very kind people about one, as our neighbours in general are, and such unusually good, intellectual, and friendly friends as the Medleys. He was a friend of John Newman, and associated with him in working at the Lives of the Fathers, etc., and Newman's secession was a great grief to him. He is awfully fond of music, and composes chants, etc. He is a fluent Hebrew scholar, and is certainly, as I told you, one of the ablest preachers I ever heard. He has been very near to going home to the council that is to be held at Lambeth, only he could not make out that the subjects of discussion had been settled, so was not certain that it would come to much, and had confirmations here, and did not like to bring Mrs. Medley back in winter, for she is nearly as bad a sailor as I am, or you might have seen them, and heard of us. They are great admirers of yours. Especially they are devoted to the Parables. Mrs. Medley told me to-day they owe you so much, she was delighted to do anything for your daughter; so you see, dear mother, you have, so to speak, provided me a motherly friend in these distant parts. She is a great gardener and a botanist, and lithographs a little.... They are going away again on a Confirmation tour directly, but meanwhile we see them constantly; they ask us in perpetually to meals, and send us vegetables and flowers. I need hardly say that Rex and Episcopus himself are pretty inseparable at "the instrument," and that Rex is appointed supplementary organist, and has joined the choir. He is going to play at the anniversary festival next Sunday, and the choir generally are quite as much edified and charmed to see the author of "Jerusalem," and quite as much astonished to find (and still a little sceptical) that "Argyle and the Isles" was not the composer, as if we all were living in a small English watering place. This you would anticipate; but you would hardly expect to hear that the Bishop evolved and propounded to me the proposal, that if I would teach him German this winter, he would teach me Hebrew. He buys books evidently with an appetite, and will lend us any, so we are well off to an extent that seems marvellous and is truly delightful.

We have free access to the Provincial Library here. This is an admirable theological and grave library, all Jeremy Taylor's, and almost every ordinary theological reference book, besides Greek and Hebrew grammars and lexicons. I am absolutely the only member at this present time! At the present moment I have all "Nature and Art" (for the water-colour lessons,) and Rex has Blunt's "Undersigned Coincidences" from the Bishop. I have Harding's "Lessons on Art" and a book on colour from the Provincial, and Alex. Knox from the Cathedral, libraries. We only want a modern foreign library to be perfect, so as to get at Schiller, or Faust for the Bishop. As it is, we mean to put him through Grimm!!!

I am just now very busy upon an interior of the Cathedral, at which I work, while Rex practises. I have got some good hints from Harding's book about drawing the arches, etc. I got dreadfully grieved at my stupidity over the colouring about here. I do wish I were a better artist! and Rex thinks I have gone back rather than forward. However, I have got some good books here, and I mean to work hard this winter indoors. I think my "interior" looks wonderfully promising so far.

I am going to save seed of all the wild flowers I can, and shall send it home, so have a nice sunny bit got ready to sow them in! You know what lives here will live with you, and some of the flowers are truly lovely. Spotted yellow lilies and splendid Michaelmas daisies grow wild, and a lovely white flower, something like a white foxglove (a Chelone glabra!), which I hope will seed itself like a foxglove, and so be easily grown. Beautiful spireas too; and oh! the pitcher plants grow here, but we have not seen them. One plant held four or five quarts of water, they tell us.

Your loving daughter,

J. H. EWING.

October, 1867.

MY DEAREST MOTHER, — I wish you could come in this moment! I have got a nice wood fire in my grate (for it is a coolish morning, one of those clear fresh mornings that I fancy we shall have pretty consistently through the autumn). I am afraid I shall hardly have time this mail, but I must make you a sketch of my room! "Sarah" has a great admiration for my table of little things (of which she always leaves the dusting to me). She says "Mrs. Coster" (her former mistress) "had a great many little things, too, not so many as you, ma'am, but then she was burnt out three times; but any little things she did save she was very choice of. She saved one plate out of her dessert service." The coolness with which people regard being "burnt out" here is amazing!! The day of the fire Sarah was telling me all sorts of "burning out" anecdotes. Some people seem to be under a sort of evil spell as regards it. "The fire hunts him everywhere." There is a certain man she told me of, and wherever he settles fire follows him!! One could make a splendid Salamander story from it in the Edgar Poe style! One comical idea one can quite understand, viz., that as much is broken as burnt in these fires often. Sarah told me of one in which, in his anxiety to save, a man flung a fine mirror out of the window into the street, to save it from the flames. Of course it was smashed to shivers!

I have got you a dial, and mean to make the sketch, and send it herewith. It is in the garden of a little old lady here, a Mrs. Shore. She is very tiny and very old. She goes to the 7.30 service like clockwork, has a garden, paints life-size portraits in oils!! and complains that, "between housekeeping, literature, and the fine arts, she never has time for anything." I sat with her last night for a bit. "Do you find the days long enough, my dear?" "Not one-half," I said; "but they say the winter is long." "You will never find it long enough, my dear."

The woods now are lovely. The autumn tints are beyond describing, or colouring. One day I began a sketch, but it is most unsatisfactory, and now it is raining, and I am so afraid of getting no more opportunity. A tree stands off against a grey woody background, and it is a brilliant yellow and crimson. Sometimes a whole tree is canary colour, and another near it one uniform rich deep red, another like bronze, and so on. They are not all so by any means, of course; but in the "College Grove," as it is called (which is something like a beautiful bit of English pasture, and park, and wood scenery), are the loveliest varieties of colour.

I had a jolly drive with the Medleys the other day. We got out and went across country a bit, over hedges and ditches, and I sketched a little at intervals. Once I said, "I really hope we may be here another summer, that I may get some of these trees done," and the Bishop groaned, "Don't talk of another summer! you must stay here forever." Rex is still at the organ, and the Bishop bristles with new chants. Rex is at work on a Christmas anthem; words my choosing.

Recit. and Bass Solo. "And Balaam said: I shall see him, but not now. I shall behold Him, but not nigh. Alto Solo. There shall come a Star out of Israel. (Chorus. A Star out of Israel). Quartet. Thy throne, O God, is forever and ever. A Sceptre of Righteousness is the Sceptre of Thy Kingdom." Final chorus not decided on. I must stop.

Your loving sister,

J. H. E.

January 26, 1868.

MY DEAREST MOTHER, — ... I must tell you about the sleigh drive. It was given by Col. Harding (who is the temporary governor as well). The etiquette of such affairs is, that the leader drives wherever he likes, and the other sleighs must go after him. (They say General Doyle used to go into the most audacious places to try and upset the tandems!) The young men ask the young ladies to drive with them as they would ask them to dance, and we old couples go Darby and Joan together. Rex got a nice little sleigh with buffalo robes in it, and the horse went capitally. We met before the House of Assembly, and kept driving round and round in circles till all assembled (about twenty-six sleighs). Then, bells ringing, red tassels waving, away we went. The colonel took us in and out about the town, but no really nasty places, and then into the barrack-yard, where the soldiers cheered, and his horses got so unmanageable that he and his young lady nearly came to grief; then out into the open country. I don't think I ever saw anything much prettier than the line of jingling sleighs, flying over the snowy roads, with the pure fields of snow on all sides broken by the dark firs and country homesteads. Once we went up a narrow hill meet to be drawn by Doré (or rather Doré might give one a faint idea of its beauty), snow pure white before us and under our feet, and great dark firs on each side almost touching over our heads. We stopped at a country inn, where lunch was prepared, sandwiches and hot spiced negus, and very jolly we were, Rex's "tscho-ga," which he wore over his coat, exciting considerable admiration.

. . . . .

Do you know we mean to "flit" this May! It will be a grief to part with the lovely views from this dear old Reka Dom, but it is too huge and too cold in winter, and burns enough fuel to — well, as one of Rex's men said, "It would take a major-general's allowance, sir!" We have our eye on a comfortable little house close by, with garden, and eight rooms in it, and they say well-built and convenient.

Your loving daughter,

J. H. E.

22 March, 1868.

People are very kind. I was walking to church when Dr. Ward met us, going off on a professional drive. He turned out his man, took me into the sleigh, and drove me to the Cathedral before proceeding on his way, that I might not have to wade through the snow. Mrs. Shore (the lady with the dial in her garden) says (she comes regularly to the daily services with small regard to the weather) that she thinks Providence always sends somebody to help her home. In this weather she needs some one, and Rex occasionally tenders his arm!

Mrs. Shore (the dial lady) is as lively as ever. We have a little joke every day almost after morning prayers. I say, "Mrs. Shore, allow me to be your particular Providence," and she says, "My dear, I was looking for you," and I give her my arm to take her home over the slippery ice.

EASTER TUESDAY, 1868.

Dear little Mrs. Shore I told you about. We have been so grieved the last week, as she has been very ill. On Good Friday she was given up, but with some difficulty the Bishop obtained leave to see her. They told him that it was no use, as she was unconscious etc.; however, she revived when he went in, and he bathed her face with eau-de-cologne, and she revived; and he sent Mrs. Medley to her, who has been nursing her since, and she is now recovering. Today, much better.

April 26, 1868.