CHAPTER I

|

Dare with determined will to burst the portals Past which in terror others fain would steal. |

| GOETHE (Faust). |

IT was for the Water of Life that Luath the great magician was ceaselessly searching.

His heart and soul were bent upon this all-absorbing desire. All else seemed worthless in his eyes, although many a strange discovery had he made during his patient seeking for that marvellous liquid which none had yet been able to find.

For several years now, Luath Malvorno had secluded himself behind the fortress-like walls of an old forsaken monastery, perched like a feudal castle on the summit of a cypress-guarded hill. All the way up, the tall trees stood dark and gaunt, a whole sombre army of motionless giants for ever wakefully watchful — rooted to the same spot in tranquil vigil of the grey old walls.

Luath's enormous wealth had driven the quiet monks from their peaceful home. He had bought the grim old building, and within the walls that once had heard but the sounds of holy chants and the oft-repeated murmur of pious prayers, this great master of the black art had fixed his abode, giving up the joy of the outer world to follow up without interruption his secret researches.

No one could tell whence he had come. The silent town that nestled at the foot of his hill could not claim him as a child of its own.

One day he had appeared in its midst, dark, tall, and mysterious, and soon his personality had become a shining light amongst its quiet inhabitants. He was feared, admired, and envied by all.

The women turned their eyes towards him, filled with the light of Love; but the little children ran away in distress when they saw him approach, and the dogs trembled and slunk aside when his shadow fell across their road.

Handsome he was; slender and upright, like a forest-grown pine, almost giant in stature, but slim, sinuous, with the gliding movements of a snake. The clothing he wore was of Eastern cut: a strange long robe of dull red tint, the colour of freshly dried blood; Eastern was also the black and gold scarf that turban-wise was wound around his head.

His great black eyes shone like two polished gems, lying hidden away behind the feathery thickness of his wonderful lashes. Dark was his face, tanned and bronzed as by desert winds; but his hands were pale, long, and gentle, with the soft movements of a soaring bird. Chin and cheeks were covered with a short pointed black beard, and when he smiled his teeth flashed from between his crimson lips, white as snow that has fallen in the night.

It was declared by old and young, by the wise and the ignorant, that Luath Malvorno was the greatest alchemist of his time.

Dark doings, it was whispered, took place behind the grim granite walls whence the white monks had fled, carrying with them their atmosphere of peace and quietude, leaving but their haunted stone chambers, to be filled with the spirits this unknown man called forth out of the shadows of the night. There was even a rumour that the mysterious magician used human blood for his blackest researches; and since he had shut himself up away there upon the crest of the hill, far out of the reach of the crowd, sinister stories were wafted from house to house, till the man's name had become one of dread.

Low-toned, creeping envy made tongues all the more malignant: why did the handsome stranger avoid their open doors, and no more move in their midst? The gossiping old witches of the town had taken to crossing themselves devoutly when the man's name was mentioned, as though verily he were the Father of all Evil in person. But the young maidens gazed up to the high pinnacles of his towers with sighs of regret.

Indifferent to the varying opinions of those who lived in the valley beneath, Luath was for ever restlessly pursuing the shadow of his great desire. All his efforts and energy, all the strained tension of his will, were concentrated in ceaseless endeavour towards the discovery he hoped to make his own.

The Water of Life!

That elusive, marvellous liquid, that would make youth eternal and death but a shadowy spectre, casting no more its terrors over his victorious way!

Neither the raptures of Spring, nor the tears of the sky, nor the furies of the storm, nor the grey silences of his abode could tear him from his work.

Without the bastioned enclosure, the bloom-laden fruit trees were thrusting their flowering branches, like long splashes of white, against the gloomy background of the cypresses that thronged the steep inclines. Amongst the loose stones at their roots, pale mauve anemones clustered in wild profusion; the swinging boughs were filled with gay-chanting birds, singing their songs of welcome to the rising raptures of Spring.

The whole world lay in spreading beauty, saturated with waves of golden light. Against the grey impenetrable walls of Luath's silent building a frail young almond tree stood out, a marvel of pink: a fairy lacework of incomparable loveliness, but so diaphanous that each gentlest breeze fanning through its branches made the tiny petals float away like soft down into the azure sky. The sweeping joy of Nature passed over the awakening earth, drawing forth colour and beauty from every crevice and corner. The ground was teeming with new, restless life — all was joy and hope and promise. A nightingale raised its marvellous voice, and sang a hymn of praise to the glory of the newborn day; the balmy air was fragrant with flowers; all was full of the promise of coming enchantment — full of the passing, fleeting beauty of the season of youth. . . .

But within his ancient time-kissed dwelling Luath sat in his gloomy vaulted chamber, poring over his wise, much-fingered books, his head leaning on the palm of his hand, a frown on his brow, deaf to the voices of Nature, blind to the charms of the bloom-decked world beyond, following with tireless persistence the thread of his thoughts.

CHAPTER II

| Beneath the shadows are depths sinking into depths, sinking, and then the unfathomable unknown. |

| FIONA MACLEOD. |

A LONG shaft of light lay over the flagged floor of the room where the dark man was sitting deeply engrossed in his studies. The chamber was huge in size, and looked as though it might once have been some holy chapel, so monumentally solemn were its proportions, so sober and mellowed its grey stone walls. Most of it was enveloped in profoundest shadow, but the inquisitive sun-rays were penetrating always farther through the tall arched window, gradually revealing a strange miscellaneous agglomeration of objects of all sorts.

Instruments of different sizes and kinds lay scattered about on tables and benches — some even were on the floor; there were flasks and strangely shaped glass vessels; stone pots and jars of quaint and grotesque forms; withered plants, and blocks of rare, dull, shimmering metals. Most of the objects were curiously colourless: all their tints were toned off, dull, dead or faded, giving them a weird, gloomy appearance, as though a breath of corruption had passed over them, blighting them, paling them, filling them with a ghastly secretive light, that held unexplained mysteries, dreadful undiscovered possibilities, awaiting to be called forth to real life. . . .

It was indeed a becoming setting for Malvorno's dark researches, well in keeping with his world-famed reputation of wizard, astrologer, magician, as a man who works with dark powers, and uses things that hide in the shadows and hate the light of day.

This livid colouring of all that surrounded him seemed the result of his unconfessed experiments; of half-born thoughts that hover, without being able to rise to clearer altitudes; of things that are best kept hidden away because they are not avowable, not made for the glare of noon, but rather for the dense shades of night. Now, with the sun shining in upon them, they were revealed in their weird gruesomeness, as a sort of living nightmare.

Faded pieces of stuffs lay over shapeless objects that seemed full of unpleasant meanings; dully glazed gems were stored away in leaden cups, beside grinning skulls and tiny bleached skeletons of rare reptiles, alongside of small heaps of unknown sticky material, damp and unprepossessing — in truth a dread collection of unknown objects, thrown about without any perceptible order.

The dancing sun-rays played over all this incongruous array, turning some of the objects into gold; revealing others, on the contrary, in all their morbid ugliness. The flooding light was out of place in this abode of dark mysteries.

But Luath paid no heed to the sunshine that even began to spangle the page of the book he was reading, and to cast coppery reflections amongst the folds of his robe.

He only looked up when the door opposite him opened very softly and a radiant apparition stood facing him, her arms full of long branches of foamy blossoms.

All the sunlight seemed suddenly to concentrate about this beautiful woman, to wrap her round with a cloak of flames — flowing down her superb figure, bathing her in wonderful radiance, and turning her pale face into a translucent dream of loveliness.

She wore a long pleated robe of that rich though sober tint of blue so loved by the women of the East. Her veil, supple and white, was held on her head by a narrow wreath of blanched violets, framing in her perfect face with snowy softness.

Her hair was divided into two thick plaits that were closely looped up over her ears, surrounding the paleness of her features with dark shadows; it was deep and rich in hue, with warm ruddy tints, as if the glow of the sun had been made prisoner amongst its glistening waves.

And what beautiful eyes she had! Strangely large and wide apart, clear and grey, with a curiously intent look, almost hard in its piercing directness; haunting eyes, over which the brows stretched in an uncurving line that met together over her small aquiline nose. There was something tender yet proud about the full curves of her living lips — a half smile played over them, but there was an enquiring anxiety in her gaze.

For a moment Luath did not speak, but stared at her with half-closed lids, as one who appraises the value of a precious object. . . .

"Aha! it is thou, Ilona," he exclaimed at length; "it is thou at last! and long hast thou been on the way!"

"Hast thou needed me, Luath?" hastily enquired the fair woman, with a catch in her breath.

"Hath not the corn need of the sun," smiled the man, "and the drooping flower need of the rain? It is several days since thou hast been within these walls."

"Hast thou needed me?" repeated the woman, laying the bundle of blossoms down before her on the table — "that was the question I put thee; forsooth I believe thou needest naught else but thy cruel self!"

"Why 'cruel,' Ilona?" laughed Luath, placing his elbow upon his open volume and gazing teasingly up into her lovely face. "If thus thou deemest me, why dost thou so often climb the weary hill that leads to my grey old nest?"

Ilona drew herself up with a haughty movement, her eyes dark with a shadow of pain. "Why do I come, Luath! hast thou a right to ask? Wouldst thou that I should remain away?"

Again the handsome man looked smilingly at her and cried in a bantering tone: "No fear of thy remaining away for long, Ilona, thou fairest amongst women; is not thy heart bound up in my researches, or is it perhaps for some other reason that thou comest to me?"

Ilona's eyes flashed, and an angry retort seemed hovering upon her lips; but she controlled herself and came round the table to where he sat, and almost timidly laying her hand upon his shoulder she looked down into his wonderful eyes; her own were filled with a strange humid light.

"Luath," she said very softly, and there was a ring of anguish in her voice, — "Luath, what need have I to tell thee why I come! Would not thy dwelling be full of all the fair maids of the town if thou didst but open thy door to them?

"Luath, Luath! thy pride is great and thy heart is of stone, but thou knowest too well that within thy old grey walls alone I find the Heaven I am seeking — wouldst thou I should seek it elsewhere?"

Luath laid his long white hand over hers, stroking it very softly with the tips of his fingers, but did not reply — there was something feline and captivating in his gentle gestures. Ilona stood rigid, upright, her eyes closed, breathing deeply, her teeth fixed in the red beauty of her lip; then, as if yielding to an irresistible impulse, she bent down and pressed her eager mouth upon the irresponsive silk of his turban.

Luath continued to stroke her small clenched fingers; his eyes, without raising themselves, seemed to guess all her emotions, and a cruel secretive little smile played over his features.

"Proud bird of Paradise," he whispered, "I feel within my veins each one of thy conflicting emotions, and sweet to me are thy unconfessed desires. I would that thy many adorers, slaves, and humble admirers could see thee with the glow of shame upon thy cheeks!"

Ilona tore her hand from beneath his caressing touch, and, turning rapidly, strode towards the open window and stood leaning upon the wide stone sill, looking down upon the marvellous world without, over which Spring had laid its garment of splendour. Beyond these walls, out there in God's great world, all was beauty, peace, and innocence — oh! why could she not tear herself away from this fatal, cruel magic, against which her soul protested, but which the hot blood in her veins adored each day more passionatelyP The burning tears of humiliation welled up into her clear grey eyes, whilst the sun kissed her flushed cheeks and lingered lovingly over the rich folds of her flowing robe.

Luath raised his head and looked after her, the cruel tantalising little smile still hovering on his half-open lips, which were red as some velvety crimson fruit.

Then he rose and went towards her where she stood.

So noiseless had been his approach, that Ilona gave a frightened start when she perceived him standing close beside her. He quietly took her hand in his, and, softening the gleam of his glittering eyes between his long dark lashes, he drew her towards him.

Unresisting, Ilona allowed him to lay an arm around her shoulder; from his great height he looked down upon her with a mocking, irritating, subtly fascinating smile. He lowered his face, till his forehead nearly touched hers, then making his voice very soft and persuasive he whispered into her ear:

"Ilona, come with me — our great work awaits us; I have new discoveries to show thee. All these days carelessly have I laboured, whilst thou, no doubt, hast been hurrying from one fine feast to another, the proud centre of an admiring crowd. Ilona, Ilona! how many are there sighing for thy smiles, feverishly awaiting a word from thy lips, a look from thy eyes? How many hearts art thou breaking, thou wild enchantress whom none can claim; tell me, Ilona, will thy proud heart ever open to let Love slip in?"

Ilona made no reply, but her soul was in her eyes as she answered his look, and once more her face darkened with that fleeting shadow of pain that passed over it, like a curtain being drawn across the light of the sun; then, rousing herself, she tore her hand from his grasp, and said in a low tone:

"Love! what understandest thou of Love!

"It may not yet have come my way — perhaps it never will! The heart can only echo to one tune, which is its own; if that tune never reaches down to its roots, it remains tuneless for ever; but that thou wilt never understand, Luath! for thou, thou hast no heart; thou art but a great, cruel brain, for ever searching thy own joy and pleasure, little heeding what suffering thou causest, for such is thy way; and verily, I believe, thy only delight is to feel thy victims writhing under thy merciless hand!

"But, come, this talk is fruitless; it were waste of breath to try and make thee understand what the sun knows so well, and the delicate seed that springs from the bosom of the earth, and the soft wind that rustles amongst the branches of the trees, — useless to try and make a cold snake feel what . . ." She broke off in the middle of her sentence, and Luath rejoined, whilst for a moment he laid his cool long fingers against her glowing cheek:

"But the snake has wonderful colours amongst the spangled scales of his shimmering skin, is it not so, Ilona? and his cold eyes have a glitter and his silken coils a luring fascination that attract ever anew!

"But, come, we lose our precious minutes, and I am eager to get to my work."

They both moved back to the great table, and Ilona, taking up her fragrant bunch of blossoms, carried them over to the other end of the room, where she plunged them into an old carved stone font, in which some ghostly-coloured tulips were already opening their pale faces, their stalks deep in cool, clear water.

"My fairy flowers are out of place here in thy morbid surroundings," she called to her companion across the room, and then coming back to the table she asked in a lower tone: "Tell me, Luath, why has all round thee this livid tone? All seems to have been blighted in some strange way, as though the whole air were full of vapours that make things sicken and die, changing their colours into tones that fill the soul with a sensation of apprehension; for, surely, my snowy blossoms will soon lose their fresh charm of spring breezes within the old grey walls!"

Luath answered with a shrug of his shoulders:

"Foolish one! I care not for what is crude and clashing; I love half tones and shadowy spectral tints; all that flares and glitters is antagonistic to my obscure researches. Only one thing must I find, and that one thing eternally eludes me: a heat that is greater than any yet known.

"Without that superior power my discoveries are all in vain.

"It must either be a flame, of which the heat has never been equalled, or a light of a strength as yet unknown; and this I cannot find; it robs me of my peace of mind and destroys my sleep at night.

"Ilona, thou wise one, thou faithful aid, canst thou not help me?" and Luath, with the insinuating gesture of a tempter, stretched out both hands towards the fair creature who stood facing him on the opposite side of the huge old table.

She raised her head and looked long and steadily into his eyes — such a direct and honest gaze, so full of questioning pain, of sad yearning inquiry, that the man dropped his hands and began playing with the different objects that lay about before him.

Then Ilona said slowly:

"Thou well knowest that I would do anything for thee — even against the will of all those that love me; is it not without their consent that I come up to thy dread abode?

"My mother cries tears of shame over me; my father is nigh upon cursing me for what he terms casting a shadow upon his honoured name, and my younger sisters avoid my company, as though I were not fit to live in their midst.

"And thou, Luath, in the cold selfishness of thy heart, thou dost taunt me whenever thou canst; yet always again I come to thee; alas, of that thou art but all too sure. . . .

"But tell me, in what way can I be of use to thee?"

She came to where he sat, and knelt down upon the floor at his feet, leaning her head against the massive side of the table.

"Luath, I wish I could help thee with thy heart's desire, help thee to find the magic water thou seekest, the water that is to give thee everlasting youth! I know that for thee that discovery would mean more than all else, more than the finding of gold, for which thou art also ceaselessly searching."

"What were gold to me, Ilona, if I lose my youth! I might be the richest man on earth, but if my hair were grey, my strength all spent, my face without beauty, my heart without desire, my wealth were then but ashes in my hands.

"I need the world as my playground, and gold to spend, and power; but youth do I need above all else, for only thus is the rest to be enjoyed!"

"And when thou hast found this miraculous water, Luath, wilt thou share it with others? Wilt thou share it with the woman thou lovest? Speak, Luath! how many wilt thou render happy with thy discovery?"

"Art thou turned moraliser, sweet Ilona! were it not better to leave that to those who have nought else?

"Why should I have thought for others! Each man for himself is the motto I most believe in. If I have brains beyond the usual average, are they not my own? Forsooth, I shall share my discovery with whomsoever I need for my happiness. The woman I love does not yet exist; one day, no doubt, she will cross my road, and then it will be time to see if I wish to keep her for ever at my side; but usually it is change a man's heart most desires, not the things that last for ever!"

Ilona heaved a deep sigh, and rose from the floor. Was the man in earnest? He was for ever a mystery to her, a dark and inscrutable problem; and each time anew she found it difficult to grasp the cruel depths of his abnormal selfishness. Yet she loved him with all the strength of her woman's heart. He had cast a terrible spell over all her being. She loved his beauty, his soft voice, his wonderful eyes, his tall grand figure, the gentle movements of his long pale hands.

She loved his intellect, his learning, she had even come to love his sinister researches and surroundings; yet he made her suffer always anew. Hardly a word did he say that did not cut her like a whip, and she knew that he was aware of the cruel charm with which he held her — that he accepted her burning adoration as a homage due to his extraordinary superiority, without ever deigning to consider the deeper wants of her soul.

And nearly every day she came again to this dark unknown man with a feeling that she was losing her soul, but drawn irresistibly towards his mysterious inexplicable personality, — she, the proud Ilona Farmendola, whose hand was sought for in marriage by the highest in the land. . . .

Humbly she came, like a poor little bird snared by the spell of a shining snake. . . .

CHAPTER III

| And he who hath to be a creator in good and evil — verily he hath first to be a destroyer and break values in pieces. |

| NIETZSCHE. |

MONTHS had gone by; summer lay warm over the fertile land; the hillside was a blazing mass of roses that tumbled in luxuriant profusion over rock and wall, sending out their tender shoots to climb up the dignified cypresses, which lent themselves with quiet indifference to the fragrant invasion so smilingly overspreading their sombre severity.

And still with daily persistence Ilona mounted the steep incline, winding her way amongst the many-coloured roses, to the forbidden walls behind which the man she loved was for ever searching for the power that eluded him.

|

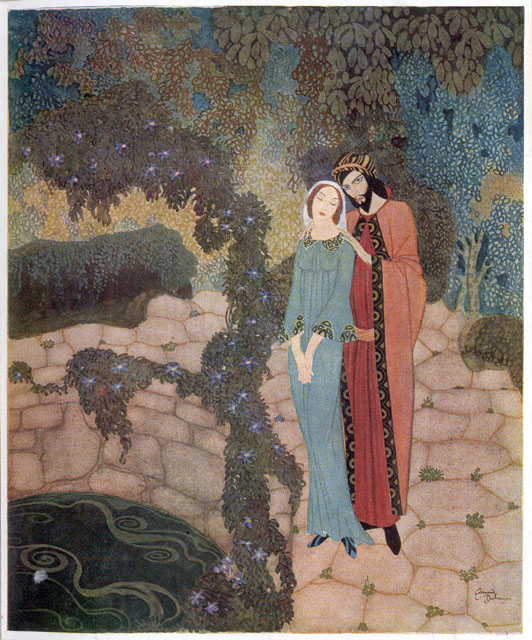

The man had his arm lightly laid across the tall girl's shoulders; they might have been lovers, so tender was his touch. |

| Page 23 |

It was the hour of sunset, and Luath was leading his fair companion from room to room in his mysterious abode, showing her nooks and corners, within which he had never yet allowed her to penetrate.

A soft mood was over the man; he had worked hard all day; he was tired and restless, so, when Ilona had arrived with the lengthening shades, he had greeted her with unusual warmth.

They were traversing the outward court that led to the hidden sanctuaries. It was a wonderful cloister of old grey stone, softened by centuries, with a hazy remoteness about its aspect that was full of slumbering repose. Here, no doubt, the peaceful monks had paced the old stone flags two and two, their white robes flashing in and out of the richly carved columns, their heads bent, their fingers twining their wooden rosaries. . . .

This evening it was a couple of surprising beauty that moved slowly over the moss-covered stones. The man had his arm lightly laid across the tall girl's shoulders; they might have been lovers, so tender was his touch; but Ilona, although her poor heart wildly beat beneath her dark blue draperies, well knew that the man's gentleness would last but a fleeting instant, that it was but a passing whim, which had no deeper meaning. Yet she rejoiced over this moment of sweetness as though a great treasure had been cast at her feet.

All along the square enclosure long beds of flowers had been planted; but everywhere the same lurid withered tones were predominant. A wild medley of poppies of strangest hues, faded pinks and mauves and greys; upright behind them, like motionless sentries on guard, stood long stiff rows of gladioli and hollyhocks. These also were weird in colour, with a metallic sheen, as though some fœtid air had passed over them, blighting their brightness.

In the middle stood an old well over the side of which a large clematis was climbing, trailing its long creepers over the steps and over the moss-softened pavement.

"This place of solitude thou knowest well, Ilona; each time thou comest, it echoes thy light tread; but to-day I have a longing to show thee other dark corners thou hast never seen. These flowers, of which the colours are distasteful to thee, are nothing in comparison to those in my secret magic garden, to which I shall take thee when the light of day has bidden us farewell.

"But first come to my chamber of silence; there I hold captive a dancing flame, which I hope may help me towards my ends. Kuskan, my faithful negro, guards it night and day."

Leading the way Luath paused before a low bronze door, wrought with some strange design almost effaced by the hands of time.

Ilona drew herself away from his touch and asked, looking anxiously up into his face:

"Luath, whence hast thou that evil-looking negro? Each time I come, he frightens me anew. Thou art almost small beside him; never before have I seen human creature so abnormally huge. I shudder when I must face his great black mask; why must thou have such a frightening servant?"

"Nothing within my walls is quite normal or usual; hast thou not yet learnt that, little one?"

"What I have learnt," sadly replied Ilona, "is that thou never givest a direct or downright answer. I know nothing of thee!

"I know not whence thou comest nor what is thy home, nor do I know thy race, nor what thy past has been; it all is dark as night to me."

Looking down upon her, Luath smiled his strange, cruel smile.

"All that stirs the imagination must be surrounded by shadows, Ilona; the bright light of day has not the charm of the evening hours, nor that of the mysterious awakening dawn.

"Certainly there are beings whose natures are as clear running water, whose souls can be read at the very first glance. But I belong not to those, Ilona, neither am I eager to be numbered in their ranks.

"What matter whence I come?

"A dark wind that blows over the earth and is gone! A heavy cloud, full of promise or fear, — perhaps a dread spirit surrounded by shifting shadows, or a grey mystery wafted through space coming out of muffled tides from the shadow of unknown shores. One day I may be gone, a passing vapour that melts into space. I cannot say for how long I am here. . . ."

"Stop, Luath," pleaded the girl, "do not make my heart ache with useless fears; stop speaking, for thy talk is always cruel. Thy words fill me with dread, as though thy house were thronged with creeping sorrows ready to spring upon me and tear me asunder."

"Come along, thou foolish one, thou art too earnest; heed not my lightly spoken words, but enter here and it will change thy anxious thoughts."

Luath pressed some invisible spring, so that the bronze door silently gave way, revealing to their sight a large low hall full of shadow and mystic depth.

A curious place, as silent as a tomb. The stone out of which it was built was as unusual and strange in colour as the flowers in the court without.

At first it appeared to be universally grey, but the longer the eye rested on its unpolished surface the more mysterious became its hue; it seemed fantastically to change into shades of blue and green and violet, like the sheen on a butterfly's wing or the shimmer of a rich-toned feather from off the breast of an unknown bird.

The great chamber was so vast that its farther end seemed dim and distant; a misty half light filled the whole place. The floor was paved with dull red stone, that gave the impression of walking over a spot where the blood of many sacrifices might have been shed.

The whole place was uncanny, brooding, full of gloom and secrecy. The centre was taken up by a deep dark tank of water, the edge of which was on a level with the red pavement. The water was perfectly still, and shimmered with a vague phosphorescent light, and right out of the middle there leapt a quivering blue flame that hovered over the surface like a lost spirit.

The two companions advanced together, their steps awakening curious echoes that ran like little mocking sounds around the walls.

When the gruesome pool was reached, they halted, and both gazed down into the dark depth which reflected their blue and red apparel in broken lines of colour. The strange flame leapt up and down, casting fitful reflections over them, lighting up their faces with an intermittent glow.

Rigid and enormous, like unto a giant of bronze, stood Kuskan the negro.

His weird coloured robe fell in straight lines along his immense and powerful body; about his waist was a heavy chain, at the end of which some unknown object was dangling, more like an instrument of torture than an ornament. Round his shaven head was wound a turban of faded orange silk that completely covered the left eye, whilst the right one was terribly watchful, its white being startlingly apparent.

So still stood this formidable figure that it might have been some startling vision risen out of a bad dream.

With arms crossed over his breast, he remained motionless, keenly attentive, his uncovered eye fixed upon his master, his two bare feet almost touching the edge of the water.

The blue flame quivered about like an anxious soul convulsed with pain.

Ilona had instinctively drawn close to Luath. This apparition of Hell was dreadful to her; he was quite like the dark spirit of evil she always felt was lurking somewhere within the house of the man she loved.

But now Luath was speaking, his fingers clasping her trembling hand.

"This flame I have guarded with utmost care. I found it one day as the sun was setting on a lonely bog that stretched for miles around, — a dreary distant place, where haunted souls met at night to cry over their pain and sorrow.

"I pursued this phantom flame as one pursues a golden dream. I caught it between the palms of my hands, and they were scorched and burnt for months afterwards, so that, my arms being swathed in healing linen, I had to relinquish all work during many dreadful days, although consumed by a thirsting desire to continue my researches. . . .

"Kuskan now watches this prisoner light, and each day it grows and becomes stronger. I have discovered that it progresses most when hovering over the face of the water, and when the water is sprinkled with . . . , but never matter with what we sprinkle the water! thy pure ears maybe would hardly care to hear. . . . But soon now my flame will be ripe for my great experiment, and that day I shall have thee at my side, dear fair woman, and it may yet be a day of triumph!

"There are different conceptions of life and happiness.

"Some care for peace, others for love, and still others for a name, and sometimes for wisdom they crave.

"For me happiness means work, power, domination, and the continual effort towards things that I must go far down to search; I love the heights of the brain, but I want to descend to seek them from out of the shadows. I want to see with my own eyes, hear with my own ears, touch with my own hands, feel with every quivering sense.

"I believe not in the light of God; I believe in the things which the brain can hold and see; and when I am tired and lonely I call up the spirits of the underworld to be my companions.

"To work for others may give joy to some; but my longing is to ride on the world, as I would ride a turbulent horse, breaking its will beneath the strength of my grip, till I feel it overcome, vanquished, at my feet!

"I want to dig where it is deepest, no matter whether the earth be clean or soiled or even foul. I want to sit where I shall be most exalted. I want to be throned alone in unreachable solitudes where only my foot can keep its balance; and when I have reached the regions I desire, then I shall look down upon those beneath me, and perchance lift one or the other to the heights I have climbed; but even then I want to remain alone in my tremendous knowledge. . . ."

The man had forgotten the woman beside him, who watched him with a dawning fear in her eyes.

There he stood, magnificent in his manly beauty, his tall body draped in dull red folds which were repeated in the quiet sheet of water beneath him like a long streak of blood; his glorious eyes full of that pride that brought Lucifer to his fall, the pride of one who worships but his own human form, believing in nought but in the power of his own great brain, defying God as once the fallen angels had done, convinced that he was an exception, above the laws that rule the universe. . . .

"I shall find the Water of Life," he continued, speaking like one in a trance who follows a wonderful vision that fills his soul with boundless exultation.

"I shall drink of it deeply, and eternal youth shall be mine!

"All those that speak evil of my name shall come crawling to my door; they will go on their knees before me and cry with the great desire to be given a single drop of my marvellous beverage, but I shall laugh them to scorn!

"I shall see their faces grow old and weary, I shall see lines of care mark their youth that once was fair, I shall watch the corroding years spread over them with their sign of decay; and I with my eternal youth, I shall stand far above, triumphant in my unpassing beauty; I shall deride their helplessness and scoff at their feeble fury, and I shall give them nothing . . . nothing . . . nothing . . . not even an instant of hope!

"Above them all in solitary grandeur, I shall pass on, walking over their heads to always greater heights; alone I shall stand exalted in my unreachable magnificence. I shall go down into the underworld to learn its most hidden secrets; I shall make friends with the creatures of shadow, and steal from them their hidden mysteries. I shall mount up into Heaven and tear from God a ray from His own eternal sun. I shall follow. . . ."

"Stop, Luath," cried Ilona, "I can bear no more; thou blasphemest; have a care; such sinful pride can but call forth the wrath of God! Defy not the powers that exist; one day they may fall upon thee and crush thy terrible assurance. Thou hast not yet found what thou seekest, thou art not yet the God thou deemest thyself. I shudder! . . . I tremble for thee, afraid to discover that what others think of thee may be true. . . ."

The man turned slowly toward her as one gradually awakening from some marvellous dream, and with one of his transient impulses that made him so dangerously captivating, he seized both her hands and gazed enraptured into her honest grey eyes.

"Beautiful woman!" he cried, "I wish I could find my happiness within these two dear, clear pools that gaze affrighted into my wicked face; but, alas, Luath Malvorno is not of those who can rest beside cool waters, he must for ever be climbing on the edge of dangerous volcanoes. In passing, maybe he will pause to bend down and touch the crystal source with his thirsting lips, but then again he must move on, — not because he has not felt the charm of the pure drink he has taken, but because his soul is restless and his brain too large, too abnormally inquiring to pause longer beside that which others call peace!"

Bending down for a fleeting instant, the beautiful red-robed figure covered the girl's eyes with his burning lips, crushing her fair face against his with a wild movement of longing; then, with a weary gesture, he passed his hand over his forehead, as though to wipe out some fevered thought.

"Come," he cried, "I dare not tarry here any longer; this place of shadows fills me with strange emotions, and a wind of folly sweeps over the coolness of my brain; I must pass on, or I shall weaken my great strength; I have too marvellous an end in view, too great a work to accomplish, to dare to squander my precious powers. Come! tempt me not, thou flower from the garden of Eden!" and seizing the trembling girl's hand, he drew her after him over the polished floor, always farther into the shadows of the hall, till he threw open a dark ebony door leading into his laboratory.

Kuskan the negro stood looking after their retreating figures, his one eye full of the light of inscrutable secrets; but upon his large lips there was a mocking smile that was strangely sinister and held a warning of sombre possibilities, . . . then he turned again towards the water, his toes just touching the cool surface, the chain round his waist swinging slightly to and fro, whilst curious, moving reflections played about amongst the heavy links. The dancing flame leapt hither and thither, like the anxious thoughts of a captive that can find no rest. . . .

CHAPTER IV

| Thy foot itself has effaced the path behind thee, and over it standeth written: Impossibility! |

| NIETZSCHE. |

SEVERAL hours had passed, and Luath drew away from the fire over which he had been bending.

He straightened his tall figure, stretching his arms over his head as one who is weary. There was a hard light in his eyes, and his lips were tightly shut.

Ilona moved farther from the scorching heat, shading her face with her hand; her cheeks were flushed, and tiny drops of perspiration hung like dew on her brow. Anxiously her eyes followed the movements of the man she loved, who was now pacing the great gloomy room with the impatient, equal stride of a caged beast of prey.

She dared not approach him nor say a word; she knew how cruel and dangerous he was at moments when his hopes had been freshly baffled.

She watched his excitement with growing uneasiness, longing to go up to him and say words of encouragement; but she, the proud Ilona, was afraid, afraid of this lithe, panther-like stranger, of whom she knew so little, but from whom she could not tear her heart away. . . .

Her soul overflowed with unutterable tenderness, knowing so well how the unbendable pride of the man was smarting under his newest failure — he had been so sure of success! so sure!

Up and down the room he strode, backwards and forwards from wall to wall, muttering words of rage between his clenched teeth, entirely oblivious of her presence, possessed by the one and only persistent thought.

Noiselessly Ilona drew near the fire again, a thin plate of yellow glass held before her eyes as protection, and looked down into the pot that hung over the flame by a chain, now red-hot. The pot was of transparent stone, very like crystal, and was filled with a dense red liquid resembling blood, except that it was thicker.

Ilona knew, from what Luath had often told her, that if he could have command over a heat that was sufficiently strong, or a light sufficiently intense for his purpose, this thick fluid ought to turn into clear water.

All his hopes had been centred on that leaping flame in the hall beyond. With incredible precautions, aided by Kuskan, this mysterious light had been carried to the fire, and there Luath had added to it various ingredients of which she understood nought. The flame had leapt about, changed colour, had even uttered groaning sounds like a creature in pain; then it had crouched low like a beaten dog, and had laid itself all violet and green beneath the crystal pot. Weird smoke had escaped all around it, taking on horrible forms, so that Ilona's soul had been overcome by trembling fear. Gruesome sounds had filled the room, and sickening odours that had stifled her, catching her breath and filling her lungs with a sensation of oppression till she felt as if she must suffocate.

All the time she had watched the dark man's face. His eyes had been full of a wild glitter; there had been something almost diabolical in his expression, as one who is very near the powers of Hell and who secretly calls up their help. His whole body was tense with tremendous anxiety, his long pale hands clenched together as though throttling some enemy.

Once he had roughly seized her and had drawn her so near the fire that her robe had been singed by the flame, which seemed less intense than the white heat of excitement that had possessed the man. . . .

Suddenly something very strange had occurred — Ilona never quite realised what it had been.

The liquid in the translucent pot had begun to bubble, and a cry of exultation had escaped Luath's lips. . . . The red colour had gradually changed into every conceivable variation of tone; then a quite thin column of smoke had risen from the centre, and this smoke had seemed alive; sounds like moaning voices had mounted into the air, and long shadowy hands had formed themselves out of the vapours; these hands had all expressed an agony of despair, and had stretched out as though imploring for help; then they had clenched their fingers with gestures of threatening, yet impotent, misery. Always more hands had grown out of the bluish smoke, and then . . . ! Oh! Ilona never forgot the terror of it . . . a horrible face had appeared, floating amidst the hazy mist, a face too fearful to describe, with an expression of leering fury mixed with pain and inconceivable torture, such as Ilona never imagined could exist. And whilst the head had thus hovered above the fire, great drops of blood had run down its grimacing mask of misery, and had fallen one by one into the crystal pot, making its contents hiss like an angry snake; and at that moment, the fluid that had gradually been becoming clearer and clearer all at once turned again into thick dark-red gore. . . !

It was then that Luath had sprung back with an angry curse that had wounded Ilona's loving ear, and she had seen no more, having covered her face with her hands, overcome by the many uncanny sights.

When she looked up, Luath was again bending over the fire with an expression of baffled fury; Ilona saw that the flame beneath the pot had gone out and that only the smouldering ashes remained, from which little wisps of smoke rose curving into the air, like phantom adders with many heads; but some still kept the form of long thin arms, that lengthened and lengthened, turning at their extremities into the long clutching fingers that seemed endeavouring to take hold of the vaulted ceiling.

What had it all meant? Ilona's brain was floundering in a mist of uncertainty; she longed to escape, to be out under the starry sky — to tear off her white veil, to loosen her hair to the fresh breaths of the wind, to feel God's vault over her head, to be away, far away from these dread revelations that were like spectres from Hell.

But she could not leave the dark man in his misery. She knew that it was his pride that was suffering, that his dream of power was slipping from him, and that he writhed beneath his impotence — he who was so wise and deemed himself lord over endless powers of magic. . . .

Up and down he paced, as one driven by some mad spirit of unrest. The dark folds of his red robe floated round him like blood-drenched banners of war. His hands were clasped behind his back, his eyes were fixed upon nothing, but had a wild look, half misery, half rage; a deep line barred his forehead between his brows.

Ilona, her hand pressed on her beating heart, watched him with the same and yet ever-new fascination, asking herself why she so passionately loved him. Were it not as profitable to love a jungle-tiger as this selfish dreamer of deep, dark depths?

Why must the heart for ever turn to that which it cannot obtain? What was this terrible law of nature that made all human beings cry out for the things beyond their reach, and stretch out their hands to what eternally retreats into the shadowy distance, leaving them with a cruel feeling of emptiness and unquenchable longing, whilst the treasures near by beneath their grip seem worthless and without savour to their restless craving for what lies beyond? . . .

Down there in the prosperous little town at the base of the hill there were faithful hearts awaiting her, and heaped-up riches ready to be cast before her feet — there were promises of wealth and peaceful homes, of joy and plenty. Yet all her soul yearned only for a smile from the careless lips of the man her heart adored, but whom her mind recognised as unworthy of such humble devotion — and that man was greedily pursuing the retreating form of an impossible hope, closing his eyes to the tangible fact that a warm live happiness pulsed at his side, casting with wasteful prodigality all its unfathomed possibilities over his road.

Must it ever be thus, that human hearts pursue each other in an endless chase, never reaching the paradise of their desires — that the tantalising mirage they are following retreats as they advance, always farther and farther into shadowy space?

Before Ilona's mind there suddenly arises the vision of a sumptuous palace, surrounded by terrace upon terrace, and out of an open window a man is staring . . . a man who is young and fair of face, and whose whole soul is calling to her with consummate longing . . . the man she was to have wedded, whose wife she was to have been. . . .

And here she stands with throbbing heart, full of cruel misery, maddened by her longing for this uncanny magician, this alien from another clime for whom she is nothing but a passing whim . . . but a breath of spring that floats over the day and is gone. . . .

Oh! oh! the pain of it all! the bitter, deep, shadowy shame!

Ilona, Ilona Farmendola, why dost thou not flee away — flee from these halls where gloom and mystery lurk amongst shifting shapes and the grey troubles of false hopes? Let not thy love become to thee as a haunted home of wasted hours . . . never more to be lived anew, dwindling away into the past that nothing can call back again. . . .

Trembling with anxiety and apprehension Ilona came out of the corner where she had been hiding, and very softly with quivering voice she called:

"Luath, Luath, can I do nought for thee?"

For a moment the man paused in his walk, but the look with which he swept her face was as one who hardly recognises a stranger. He crossed his arms over his breast and gazed at her. His eyes were as dark as death, and their burning sullenness pierced her through and through.

There was a strained silence, and then, as though awakening from some deep slumber, he sprang towards her, and seizing her roughly by both hands:

"Go!" he cried, "go! before I lose my head! I cannot bear the sight of thee just now — go! or I could do thee some harm. It is fearful to me that any living creature should have seen me in a moment of failure.

"Right I was to wish to work in lonely seclusion; it was damnable weakness that made me keep thee at my side, therefore no doubt did the spirits join forces against me — a man with my aspirations must not have a woman prowling around him. . . ."

"Luath," protested the girl with blanched lips, "how canst thou speak to me thus? — thou knowest how I thirst to help thee and to be thy comfort. Luath, I pray thee, let me remain, let me . . ."

"I need none of thy comfort and none of thy weakening pity — go, I tell thee! leave me! I cannot bear the sight of thy snow-white face . . . what seekest thou here? dost remain to mock me in my hour of humiliation? Or art thou perchance dreaming of sweetening the night for me with the honey of thy kisses?"

"Luath!"

It was like a cry of pain, the wail of a tortured soul, and the poor girl with a sob of misery covered her face with both hands; then gathering her white veil around her, she hid her burning shame within its silken folds, blindly she sought for the door, stumbling as she went, so eager was she to escape . . . at last she found the handle, turned it, and swaying like a storm-beaten reed she found herself once more in the great gloomy hall of strangely gleaming stone.

Here she paused for a moment taking breath, leaning against the ebony door she had closed behind her.

As she stood there, vainly trying to master her surging emotion, something shadowy and enormous rose suddenly out of the dark and towered above her like an evil spirit.

Kuskan! — oh, the horror of it! — she had forgotten that he guarded with sinister watchfulness his master's door! Luath generally let her out himself by another way, and now in her haste to flee from the magician's cruel words, she had almost run into the arms of this giant savage whom all her sharpened instincts keenly distrusted.

Suppressing with a great effort the cry that mounted to her lips, she drew herself up as bravely as she could and faced this spectre with the leering face.

Something told her with irresistible certitude that this dusky, slinking slave hated her with the stealthy jealous hatred of a watchful dog, a hatred which he repressed when his master was present. But he resented her visits to the solitary castle, of that she was convinced, afraid that one day she might steal his place.

The orange turban on the man's head had slipped slightly from his forehead and revealed what Ilona had never yet seen — an empty and blood-red socket out of which the light of life no longer shone; it appeared to the girl's overwrought nerves as a horrible wound, clamouring with silent lips for some deadly revenge. . . .

The man came quite near and, crossing his arms over his broad breast, stared at her with his one over-bright eye; he seemed also to be staring with that gaping red hole, and the vision of that marred, sullen black mask was so terrible that for a short unreasoning instant she covered her face with her hands.

"Aha! the innocence of thy candid eyes cannot bear the sight of my mutilated face," sneered the dark fiend in Ilona's own tongue, but with such a strange accent that it made his words all the more ugly to hear. "No doubt the beautiful, soulful countenance of my handsome master pleases thee more than my brute-like blackness! I would thou couldst hear what all thy townsmen say of thee, what names they give to thy unavowable passion for Luath Malvorno! Methinks thou wouldst hardly care any more to lift thy proud head amongst them, thou whom all treated as their uncrowned queen. Good for thee it were to listen to the honeyed words, to know their gentle prattle!

"But come with me; what I can show thee will perchance open thy eyes to things thy fascinating magician has not yet revealed to thy delicate senses, which forsooth will be none too pleased. . . ."

Ilona, shuddering, felt how a heavy clawing hand clutched her wrist, and as one in the throes of some ghastly dream she let herself be drawn always farther over the blood-coloured floor, always deeper into the gloom of the vast low hall.

The light no longer leapt hither and thither on the face of the silent water, only a faint gleam still spread over its sleeping surface, giving it the appearance of some crouching secret which lies awaiting the magic hand that will call forth its hidden life from the unfathomed depths. . . .

Ilona could not rid herself of the iron grip that bruised her soft little wrist; she was compelled to follow her savage aggressor, who dragged her rapidly past the dark tank, till a small door was reached on the farther side. This her assailant pushed open with a rough movement of his shoulder, and she found herself in a small dark space where, as she entered, a sickly smell filled her nostrils, and so pervaded the air with nauseous vapours that she all but swooned.

Kuskan took a lantern that lay on the ground, and swung it about so that the wavering light lit up all the corners in turns.

One look was enough for Ilona — it was as though she had peeped into Hell . . . a small cellar-like room with walls of stone, and on the damp floor, only partially hidden by blood-stained covers, were scattered heaps of nameless horrors and dark shapeless masses — if human or not, Ilona did not pause to investigate. . . .

With a mad cry of distress she wrenched her hand away from her terrible companion, who was bending down to lift one of the cloths from the indescribable something that lay stretched close at their feet, and swift as a chased deer she fled, driven by her wild terror and frantic desire to escape, never pausing till she had slammed the great outer door of the castle behind her.

How she got out, how she eluded the ghastly black fiend, she never knew. It was her uncontrollable, overwhelming terror that lent her strength and agility never before put to the test. . . .

Panting, overcome with dread, her knees giving way beneath her, she rushed in a headlong race down the stony path, winding her way, fleet as a hunted hind, in and out of the dark cypresses, scratching her hands and tearing her flowing robe against the creeping growth of roses.

She never paused to look back, but all the time the hideous vision of what she had just perceived, that ghastly revelation of undreamed-of depths of horror, haunted her fleeing steps.

How could such a thing be possible — there amongst so much beauty, amongst those hidden sanctuaries that had once been hallowed by heavenly chants and the fervent service of God — how could the man she loved work quietly beside such a chamber of darkness?

One moment she stopped, having reached the bottom of the hill and hidden herself beneath the dense shadow of a huge tree; she looked up to the grey building and towers of the gruesome dwelling from which she had fled and saw how a solitary light burned in one of the windows.

It was now nearly night, and the small red glow that shone so strangely from the dark masses of the fortress-like walls reminded her of Kuskan's horrible malignant stare, and yet she knew that that single lamp marked the room where the proud searcher of dark mysteries was working all alone.

Her heart drew itself together in pain as she watched that faint, far-away gleam; at times it seemed beckoning to her with kindly invitation, and then again it became Kuskan's awful hollow socket, threatening her with unspeakable horror.

How would she ever have courage to go up there again? and yet love was stronger than even fear or humiliation, and she felt a bitter yearning for the hard selfish man, who had turned upon her with such cruel words. Woman-like, she believed that somewhere beneath his outward hardness there must be a vulnerable spot, if she could but reach it; horrified as she had been, she well knew that she would not have the strength to resist his call if he needed her. She despised herself for her weakness, hated herself for her want of pride, but it was useless to struggle against this mighty flood which always swept her anew towards the being from whom she longed to flee. She felt like a defenceless prisoner who cannot break his chains!

With a hard sob she turned her face to the rough bark of the grand old tree, and hiding her burning cheeks in her hands she burst into tears. . . .

CHAPTER V

| Your path lies open before you, but you have cut off my return and left me stripped naked before the world with its lidless eyes staring night and day. |

| TAGORE. |

"ILONA!"

The girl looked up with a start from the embroidery over which she was leaning, and rose respectfully from the seat near the window, to greet the tall lady who was coming towards her.

The two women faced each other without a word. Ilona's head was held high and an expression of defiance was in her fine grey eyes, although a pathetic, questioning smile hovered round her lips as though she were longing to give way to a softer emotion.

Her mother sat down upon a high stiff-backed chair, drew her rich velvet draperies around her, and passed her hand over her snow-white coif, which lay in immaculate folds around her handsome face, as one who wants to gain time and hardly knows with what words to begin a painful subject, that can no more be avoided.

The elder woman was as beautiful as her daughter, except that the bloom of youth no longer lay over the saddened features, which life had chiselled into the relentless lines of those who have seen too much.

Silently she gazed at her daughter, who stood before her, leaning against the oak panelling of the handsome old room.

To-day Ilona was clothed all in white, and a spotless head-dress, resembling her mother's, framed her lovely face. Somehow she looked younger in this maidenly attire, less of a grown woman, softer, more gentle.

Leaning over the table towards her daughter, the woman touched her hand. "Ilona," she began in a low voice, "sit thee down, I must talk to thee; my heart is heavily burdened because of thy behaviour, and it leaves me no rest."

"Mother," said the girl, sinking into the seat opposite her, "yes, I suppose we must talk — but, mother, I tell thee, I am afraid that all thou hast to say to me is in vain!"

"Ilona! how canst thou speak such words? Thou knowest well how thy behaviour grieves us, how thy name is becoming a byword through all the town! — how those that love thee best are beginning to shun thee, to look askance upon thee. Ilona, thou wert once the idol of the town, the pride of thy parents, the sunny joy of thy sisters and friends, and now, Ilona, since . . . "

"Stop, mother! I know, oh! I know but too well, I know it all, I feel it deeply in my own aching soul — thinkest thou, mother, that it is easy to slink through the streets with bowed head, I, who once used to sweep along as a queen, the little children flocking from far and near to kiss my hands, and now even the beggars grin when I pass. . . . Mother! mother! believe me, it is not easily that I have slipped from the pedestal upon which I used to be throned!"

"But, child," cried the mother, "if it is thus, why dost thou not tear thyself away! It is not too late; if thou dost cease thy solitary wanderings to that awful castle, soon the evil talk will die down; thou art young, thou art beautiful, the name of Farmendola is loved and respected, and, child . . . " softly the mother caressed the beautiful girl's hand, and almost in a whisper she added: "child, dear, thou knowest how there is one waiting for thee with faithful, unshakable trust, but whose heart thou art slowly breaking. Child, dear, dost thou never think of him? . . ."

With dry eyes Ilona stared across the room without answering. There was a painful silence, during which the elder woman watched the younger one with mortal anxiety; then wearily Ilona passed her hand over her brow and spoke in a toneless voice:

"Once upon a time there was a woman; there is none who knows not her name. The woman lived in a beautiful garden, where all was hers except one tree . . . one single tree; round that tree a circle of light had been placed, above which these words stood in flaming letters: 'Of this fruit thou shalt not eat.' That woman had all her heart could desire, everything she had . . . peace and beauty were hers, the blue of the sky, the flowers of the fields, all the other fruits of the earth — a man she had at her side whom she loved, and God was near . . . God was her friend, and yet, . . . well, it was that one fruit, off that one tree, that she craved to taste, and all the glory around her, all the boundless riches, the sunshine, and the whispering winds amongst the branches, the fresh dew of the dawn, the cool water of the rivers, the myriad stars of the night, the thousand voices of the birds, the glory of the awakening morn, the flaming colours of the setting sun, none of these could suffice her — she had to taste of that one fruit, just of that one forbidden fruit . . . !"

Stretching out her arms over the table and hiding her burning face upon them, Ilona continued: "Mother, it is all no good, this madness is upon me, this deadly poison has penetrated within my blood, it flows like fire in my veins, so that all else has lost its meaning for me. Dost realise, mother, that if the bleeding hearts of those that love me were lying there before me, barring my way, mother! I would walk across them; tread upon them with my feet, if he were to call me to him! Mother, I know he is dark and evil, that he is an enemy of God. I know that he is selfish, cruel, he even treats me as if I were but the dust beneath his feet, and yet, mother, if he calls . . . well, if he calls, mother, I shall go to him . . . yes, I shall go!"

"Child, my poor child!" cried the horrified mother, springing from her seat; and going to her daughter she gently raised her bowed head with both her hands: "I cannot bear to hear thy awful confessions — I knew not that thou feltest thus! But I must save thee, I must; I cannot stand by and see thee going thus to certain perdition. For two weeks thou hast not been up there on that awful mountain; child, I have watched thee with ceaseless, silent anxiety, and new hope has begun to rise in my nearly despairing heart. Listen to me and I will save thee! Come away with me, child! Thy father shall purchase a strong new vessel, and together we will sail over the wide blue sea to some distant land . . . and when the ocean lies between thee and thy folly . . . then, Ilona, my dear one, thou wilt see how much easier it will be! Child, wilt thou come?"

Ilona had risen and stood erect, as motionless as a pillar of salt; then slowly she turned to the window and threw it wide open and stared out upon the peaceful town, over the silent, grey, rose-covered houses, over the high church steeples, up towards the bright blue sky, and there with its towers touching the filmy, floating clouds stood the grey ill-famed monastery, rising above its surroundings like a grim fortress, its sombre secrets hidden behind its bastioned walls. Long did Ilona gaze upon this familiar picture, as one who cannot tear herself away, and then with a groan of anguish she fell with her head on the hard cold sill, and sobbed as if her heart would break.

"Yes, mother!" came her muffled voice, "I will come, but take me quickly, oh! quickly away!"

Several days later all was ready for Ilona's departure; a breath of relief had passed over the Farmendola palace, and hurriedly all was being prepared for a long absence.

Ilona's father had been begged by his wife not to say anything to his daughter, never to mention any single painful subject; nevertheless he found small loving ways of showing his daughter his approval — but Ilona passed amidst all the fuss and excitement with haunted eyes and the pale face of a ghost.

The last evening had come; the sun was sinking after a hot late summer's day, and welcome indeed were the restful shadows that slowly, like a cool veil, laid themselves over the tired earth.

Ilona sat motionless with dry eyes and idle hands at her own small window, her arm leaning on its sill, her chin in her hand, gazing, gazing towards the drear grey walls. . . .

Suddenly the little red light glowed at the window she knew so well. From far it appeared to be but a small gleaming fire-fly, and yet her heart too well knew whose lamp it was.

At the sight of that small beckoning spark, a slow tear detached itself from her long dark lashes and fell like a trembling diamond into her lap. She did not raise her hand to wipe away the warm drops that now chased each other down her pale cheeks, she did not even know that she was crying, but her eyes were unwaveringly fixed on that one tiny steady light.

Some one softly opened the door and a small folded piece of paper was silently laid on the sill at her side; she did not raise her head to see who it was, nor did she at once stretch out her hand for the paper.

Then with an indifferent movement she drew it towards her, cast a look upon it, and sprang to her feet with a smothered cry. . . .

And that night Ilona Farmendola stole away out of the house of her parents and, like a thief, threaded her way back through the tall cypresses, always higher and higher, till she reached the dark tempter's dwelling . . . cutting off behind her all hope of return.

CHAPTER VI

|

Loving and perishing; these have rhymed from Eternity. Will to love: that is to be ready also for death. |

| NIETZSCHE. |

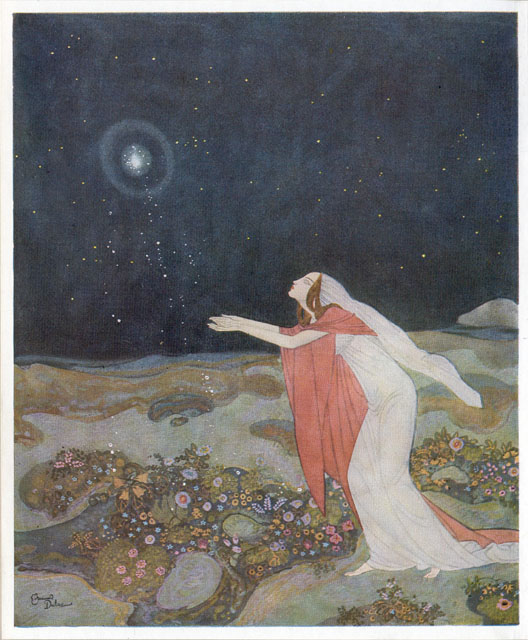

THE moon was shining down in floods of silver upon Luath's magic garden.

High unscalable walls shut it in on all sides. It was small and square, and the ghostly light gave an added mystery to its already uncanny appearance.

The whole enclosure was paved with the same dull red stone as the gloomy hall within. In parts these slabs had been replaced by broad beds, where extraordinary flowers grew in rich profusion — flowers more like weird deep-sea growths than garden blooms. All were pale and enormous, with morbid livid colouring, and a perfume of overpowering sweetness which rose out of their wide-open calyxes.

Up against the high wall, standing in regular rows, were tall stiff plants resembling sunflowers in size, but they had strange blossoms, like pale tormented faces of a dead mauve shade, and all their heads were turned in the same direction, as though listening and waiting for some dreaded master.

In the centre of this garden was an ancient stone altar thickly overgrown by a creeping plant, the flowers of which were like copper-coloured spiders, and clung to the grey stone with long feelers resembling those of some gruesome insect.

On the altar, whence the figure of some venerable saint or the mild smiling countenance of the Mother of God should have looked down with placid serenity, sat a squatting idol with hideous face — an idol that grinned in silent impassible mockery upon its surroundings. Upon its forehead a precious stone shone with changing lights like a wicked eye. Out of the crevices between the slabs of granite blue flames rose in thin wisps, which curled round the metal monster, hiding its uncouth form with a veiling mist.

A small door in one of the walls was now gently pushed open and two figures entered, the one with eager buoyant tread, the other hesitatingly, with the shrinking movements of one who draws back in fear.

It was Luath, and clinging to his hand, Ilona followed him, her face pale and drawn, her eyes wide open, full of anxious questioning. But the man's face was alive with keen delight — his whole being seemed full of ill-concealed pleasurable excitement, which he strove to soften into tenderness.

Never had his tall red-draped figure been more magnificent, his tread more elastic, his dark countenance more fascinatingly handsome. Glowing exultation was written on every feature, and some uncontrollable emotion made his hands tremble, as he led his fair companion to a marble seat in the most secluded part of the garden.

The whole atmosphere was dense with unrevealed mysteries, palpitating with unknown secrets; the whole air was full of breathless expectation. A grisly silence lay over the place.

Ilona sat down and looked about her, turning her head very slowly from one object to another, whilst her eyes still retained the same painful, strained look. Her throat was dry with suppressed sobs; unshed tears burned beneath her lids; upon the dark blue of her robe her two pale hands were painfully clenched. With the movement of one who shivers, she drew her cloak around her, a cloak that was, curiously enough, of the same tint as the raiment Luath wore.

"Art cold, Ilona?" softly enquired the man, as he seated himself beside her; "rest awhile and thou wilt soon feel better — thy heart beats, I see how it lifts the folds on thy breast. But how pale thou art! what ails thee?" He took one of her hands in his with a gentle gesture, and began stroking it softly with loving solicitude.

Ilona did not draw it away, but remained silent, turning her great eyes up to his face with an expression of dumb pain.

Slipping to his knees at her feet, he drew her towards him and whispered, "Ilona, dearest, I have never seen thee thus!"

Still she was silent, but as she earnestly looked at him with her beautiful haunted grey eyes, her trembling lips painfully tried to smile, and she stretched out one of her hands and timidly laid it on his head.

Eagerly the man questioned her, drawing her always more closely towards him, till he almost heard the fast beating of her heart against her dress. But still Ilona said never a word; each time her lips moved, it was to her as if something choked her voice within her; she was quite powerless to utter a sound.

"Ilona, dearest! thou hast been suffering — I see it well. Tell me, Ilona, what it is; perhaps I can ease the burden of thy heart."

"Ah! surely it were in thy power," whispered the girl at last, "for only those that we love can help us, those that love us have no force to deaden our suffering! but to be with those we love is a help in itself!"

"Lovest thou me, then, Ilona?"

"Is it to add to my sufferings that thou askest?" was the girl's rejoinder — then, as speaking to some unseen being, she continued:

"There once was a time, when Ilona Farmendola was white as snow, and when the folds of her robe showed never a stain. Now the dress she wears is soiled, and its hem is covered with mire. Once the sun shone down upon a girl that was loved and respected, and now that same girl avoids the light of day and seeks the darkness of the night to hide her shame. Once there was a soul within her that was free, now her soul is bound with a thousand chains of pain and humiliation.

"Once she had a mother . . . now she has nothing more! . . . nothing! not even the path upon which she came. Her feet can no more carry her back, never more can she retrace her footsteps; it is only always farther that she can go. And like a beaten dog she returns to the master that ill-treated her. . . ."

"I? strike thee, Ilona! how come such words into thy mouth? I never touched thee! not a single hair of thy beautiful head did I touch!"

"It is not always with the hand that one strikes, nor is it physical cruelty that most hurts — the last time I was here . . . " and Ilona paused whilst her eyes were full of the anguish of her dark experiences, "the last time, oh! Luath . . . it was awful — awful! and Kuskan, thy terrible murderous Kuskan, thou dost not know to what he dragged me, what he forced me to look upon! Neither dost thou know how thy words tortured me and drove me from thee . . . and now, now I am nowhere at home. Nowhere!

"I was to have left, I wanted to go from thee, to be saved from my own sinful weakness . . . my mother promised to free me from the fetters of my shameful folly . . . but then came thy call . . . and I thought . . . I thought that perhaps thou wert in need of me . . . and like one mad I fled. . . . I fled from those who could save me, back . . . back to perdition!" And the poor girl covered her face with her hands, shielding her painful blushes from his searching gaze.

Luath rose from his knees and seating himself on the bench beside her, drew her towards him till her head rested with a weary sigh on his shoulder; then, leaning his dark cheek on hers, he whispered in a voice as soft as the gentlest forest murmur:

"Not to perdition, Ilona — ah! no, speak not thus bitterly to me! Yes, I need thee, thou beautiful woman, therefore did I call thee to me. Forget the visions that last time darkened thy soul. I was crushed by a cruel blow, writhing under the effects of a humiliating failure — therefore were my words hasty and cruel! Forgive me, I pray thee. Canst thou forgive?"

Ilona raised her head and looked sadly at him with her habitual steady gaze.

"Forgive thee? alas, thou art always forgiven, even whilst thou strikest, and therefore no doubt wilt thou strike again! for is not my cowardly surrender an inducement for thee to use me ill once more?"

"But, Ilona, for what cruel monster dost thou take me, that thus thou judgest me?"

"It is said that love is blind," slowly answered Ilona, "that love is blind . . . maybe that it is true, when said of a love that is happy, but I tell thee that love which is one with sorrow hath a thousand eyes.

"Thinkest thou that I do not know that I am less to thee than the ground over which thou treadest!

"But the love of woman is deep and lasting, and knows neither why nor wherefore. When it gives, it will always give again; neither does it enquire what it will receive in return; it gives because it lives from its giving, and the more it draws from its hidden treasures the more treasures it has. I want nothing of thee, only the permission to be at thy side and to help thee in thy work!"

"Indeed, is that thy wish?" queried Luath, and a strange gleam came into his eyes and a curious ring sounded in his voice — "is it verily thy dearest desire?"

Gravely Ilona bent her head in sign of assent; her gaze resting in mute enquiry upon his face awaiting what was to come. For a moment Luath hesitated; then, drawing her head once more upon his shoulder, he began in a voice that quivered from an overpowering emotion he could barely control:

"Yes, thou canst help me, Ilona, thou alone; and now in this hour of sweetness, when the moon with her pale face looks down upon thee and me, here in my magic garden, where no mortal eye can pry on us and no unbidden ear listen to our voices, I shall speak to thee of something that is very wonderful.

"Ilona, I have called thee unto me to let thee prove to me that thy love is not an idle word! Lie still, dear one, thou art well there with thy dear face so close to mine — it is like a breath out of the unknown to feel the softness of thy skin against my cheek . . . but listen, Ilona, and when thou hast heard, then canst prove to me how great is thy love. . . ."

The tempter paused for an instant, searching for his words, afraid of alarming the girl, and thus losing what he so ardently desired to gain.

"Ilona," he began at last, "it is full of wonder what I have to reveal to thee, and at first it may make thy heart afraid; but if in truth thou art strong in thy love, then the desire will awake within thee to help me in this my highest aim. . . . " Once more he paused, and a slight trembling passed through his body, so that Ilona laid a gentle hand on his, with a gesture of encouragement — then again he spoke:

"I have heard of a light such as no one has yet seen on this earth, a light of such marvellous intensity, that none can be compared unto it . . . but, Ilona, this light lies in the human heart of a man . . . !"

Ilona started and sat up, gazing with an expression of fear into his face. "What sayest thou! in the heart of a man? have I rightly heard, or are perchance my wits quite clouded — how dost thou wish me to believe such a tale!"

"Patience, Ilona, and let me speak, for, indeed, it is hard to believe this which I am relating with simple words!

"Thou knowest how I failed in my last trial; how the spirits were against me; thou didst see the horrible face that leered at us through fumes of smoke, how the great drops of blood fell one by one into my Water of Life, clouding its clearness? Since that day of bitter failure I have been restless, searching and seeking night and day. . . .

"And one night there came a spirit unto me, revealing to my eager brain a wonderful mystery. . . .

"In a far-off desert, of which I know not the name, but which I shall nevertheless be able to trace, there lives a man bearing the strange and unknown name of Alawyiola; a man who carries a light in his heart. Once, it seems, he lived amongst men — but now he has gone into solitude to ponder upon the things he has seen.

"The world and those that live therein give him different appellations: some call him a saint, others an anchorite or a prophet, but most call him a fool! — but listen! that man went into the desert to pray and to prepare for what he deems his work, and it is said that the light he bears in his heart is of a force beyond all that has ever been known, a force that nothing can equal. . . ."

"But," cried Ilona, "what good can that light be to thee? for I hardly believe that thou tellest me this without some dark end in view."

"Wait, Ilona, and thou shalt know! This light can only be stolen by a woman's hands. . . ."

"What!" interrupted the girl, "a woman's hands can steal that light! and thou . . . oh! Luath," and she sprang from her seat and stood tall and trembling before him, a dawning fear in her eyes, "and then . . . thou hast thought of me! I . . . with my two hands am to tear that heavenly radiance right out of a human heart! Oh! Luath, dark and fearful are thy thoughts!"

"Hush, Ilona, and listen! What tells thee that that light is his life? and that he cannot exist without it? Would it not have a thousand times more value within my hands! I tell thee, that light alone would be strong enough to help me solve my great secret! More than one spirit did I call up to ask their advice; one and all confirmed what their shadowy brother had told me! and so it is that light I must have, that one and none other! Ilona, dearest, be not afraid. Is then thy love so weak?"

"My love?" her voice came in a whisper; "my love, oh! is that the meaning of thy calling? and my foolish heart that thought, that perchance . . . oh! Luath, Luath! always anew dost thou stab me with a thousand daggers, always again dost thou trade with that soft and vulnerable object — a woman's passionate heart! Therefore didst thou call me, only therefore . . . to persuade me to risk my own soul, to persuade me to become a Stealer of Light?"

"A Stealer of Light! Ilona, does it not sound grandly sweet; how many would give years of their life to be thus called! yes, Ilona, let us become Stealers of Light! Thou and I! and when the light is in my hands, then thou wilt see what power will be mine! And then I shall crown thee with my success, lift thee up to my side, make thee my loved and honoured companion for ever — I shall offer my marvellous beverage to thy lips, and thy wonderful youth shall be thine for ever — were it not worth the sacrifice?"