THE INDIAN ALPS

AND

HOW WE CROSSED THEM

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY.

|

There is a spot of earth, supremely blest, A dearer sweeter spot than all the rest. — MONTGOMERY. |

O SCARLET poppies in the rich ripe corn! O sunny uplands striped with golden sheaves! O darkling heather on the distant hills, stretching away, away to the far-off sea, where little boats with white sails, vague and indistinct in the misty horizon, lie floating dreamily!

How exquisitely the soft neutral grey of the sea contrasts with that bit of bright sandy beach, and the crimson clover with the canary colour of the sunlit meadows! One's sense of harmony is never ruffled or disturbed by the colours on earth's broad palette. The sky, flecked with fleecy clouds, is soft and blue. Lights and shadows, ever shifting, play athwart the quivering fern-brake, just showing the first warm tinge of autumnal splendour. All nature inanimate is immersed in the semi-slumber of noontide. Now and then a buttercup nods its head as though it were napping, and on a harebell stalk a butterfly poises itself, with a gentle see-saw motion, as if rocking itself to sleep. Nothing seems really awake but the bees, still buzzing about the wild flowers; but even they are gathering no honey, as far as I can see, and are only pretending to be busy. The very rooks have ceased to whirl round those old elms yonder, and, congregated on the church tower, which seems to keep guard over the quiet dead in the churchyard beneath, are far too drowsy to enter into animated conversation. Occasionally an argumentative bird sustains a prolonged caw, but finding no one in the humour to contradict him, he soon subsides into the general stillness.

But see! the upland there to westward, bathed in a flood of ambient light an instant ago, is immersed in sombre shade, as a cloud floats lazily between it and the sun; and, hidden before, now bursts into view, as if by magic, a thatched cottage, the one salient point of the whole landscape. Within the doorway the movements of the cotter's wife may be seen, at some occupation, and a little picture of rural contentment and quietude has been created in a moment. She comes out, and a charming woman she proves to be — charming, that is to say, in an artistic sense — something orange about her neck, and wearing a madder-coloured gown, whilst a small red-and-white child toddles after her. She has evidently come out to feed the pigs, by the clamour they make at her approach, and there is no need to ask the hour, or note that the sun is at its meridian; for, entering by the wicket, comes the goodman home for his mid-day meal, and from the steeple, surmounted by its weathercock, which gently swings from side to side, the clock strikes twelve, its cracked bell the one bit of discord the ear needed to make the harmony complete.

Why at this instant does the bright blue ribbon round the neck of my little Skye terrier sitting beside me look out of 'keeping'? Why does his sharp civilised yap-yap grate on my ear, as he gazes beseechingly in my face for a token of permission to be off to worry the pigs? Why would a female rustic in ragged attire, sitting on a sunny bank, be more in harmony with nature than one wearing the 'last sweet thing' in hats, its feather just at the particular pose of the year eighteen hundred and seventy — no matter what? Is there no affinity between Mother Nature and the wearers of purple and fine linen? Must we be sons and daughters of the soil to render us one kin? There is poetry in that ragged time-worn thatch, with its tufts of weed and moss growing out of every available cranny; there is poetry in the cotters wife and her little red-and-white child; there is poetry even in those squeaking and excited pigs, quarrelling greedily over their 'wash.' Then why not in me and my Skye? In what consists the picturesque?

Such questions as these I used to ask in the golden days of childhood, and on one occasion received a severe snubbing from my governess, who, shaking her head ominously, predicted I should grow up to be a visionary creature not fit for this world, bidding me the rather be practical and get on with my geography. For in those days of my non-age nature was ever a delight to me, and I could draw a landscape pretty accurately, the trees it may be too much like Dutch toys, and the perspective somewhat startling; for has not one of those brilliant productions been preserved by loving hands through all the vicissitude of the chequered past, wherein I am represented in conventional pinafore standing at a window listening to the warbling of a sentimental bullfinch as big as myself? But the 'three r's' were an abomination unto me, and geography the very bane of my existence. How little I thought then — ah me! how little any of us think in that Paradise of childhood, when our future lives are to be 'so happy,' where the paths are to be hedged with thornless roses and the flowers to be all 'everlastings,' none to be gathered by the reaper Death — how little I thought, I repeat, in those days whilst she endeavoured to impress upon my unlistening ear the position of the Himalayan mountains, that in after years I should climb their heights and be able, as now, to recall to mind visions of fairer scenes and fairer skies than even that on which my eye is resting, and behold such grand things in God's beauteous earth, of which man in his philosophy never dreamt.

But are there scenes more fair than those in our own dear land? Well, perhaps not fairer, for nature is sweet in her homely English garb. I love these scented meadows in the glorious summer time; I love these rounded hills and sloping pasture-lands, telling of centuries of peace and plenty; but there are scenes which to look upon make man humbler, and, I think, the better; and even as I sit here quietly drinking in all this placid, tranquil beauty, I am seized with a spirit of unrest, and long to be far away and once more in their midst. Would you see Nature in all her savage grandeur? Then follow me to her wildest solitudes — the home of the yâk, and the wild deer, the land of the citron, and the orange, the arctic lichen, and the pine — where, in deep Alpine valley, rivers cradled in gigantic precipices, and fed by icy peaks, either thunder over tempest-shattered rock, or sleep to the music of their own lullaby — even to the far East, amongst the Indian Alps.

|

Kennst Du das Land wo die Citronen blühn, Im dunkeln Laub die gold Orangen glühn, Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht. Die Myrte still, und hoch der Lorbeer steht, Kennst Du es wohl? Dahin! Dahin! Mocht ich mit Dir, O mein Geliebter, ziehn. |

| GOETHE. |

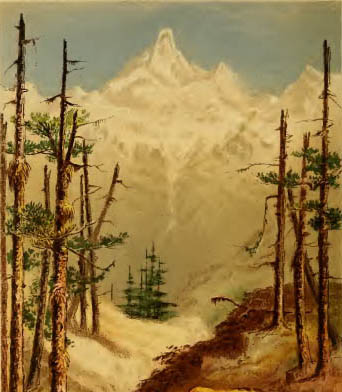

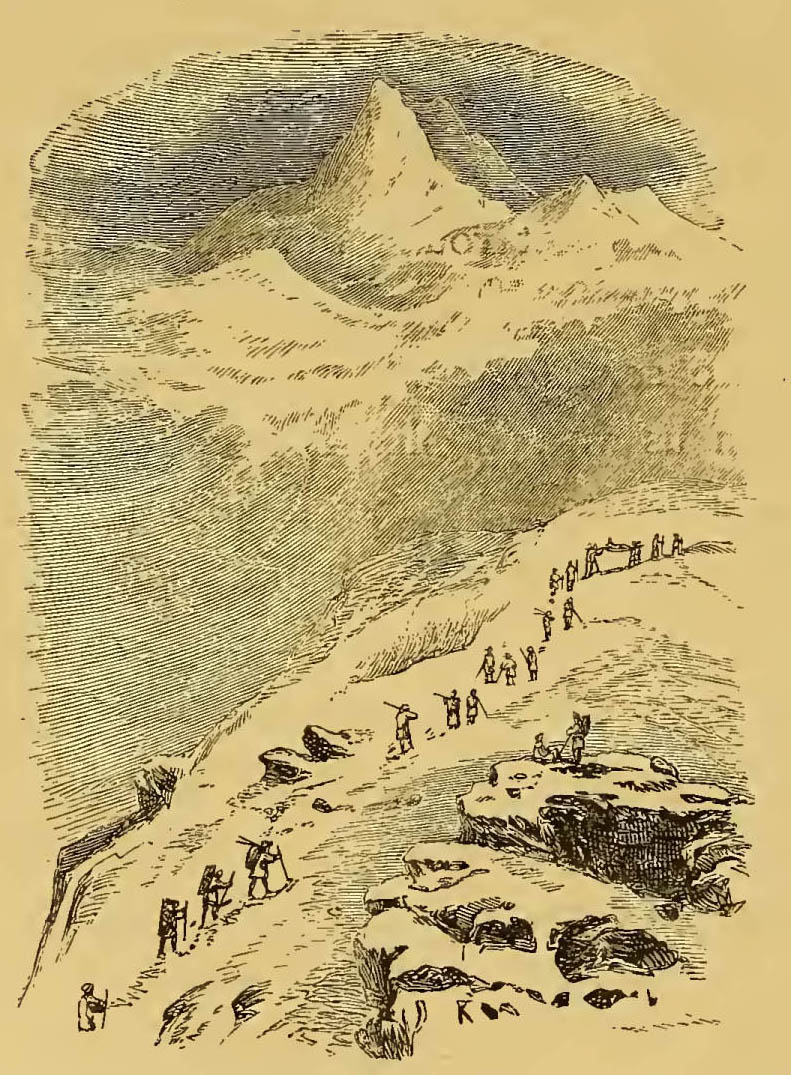

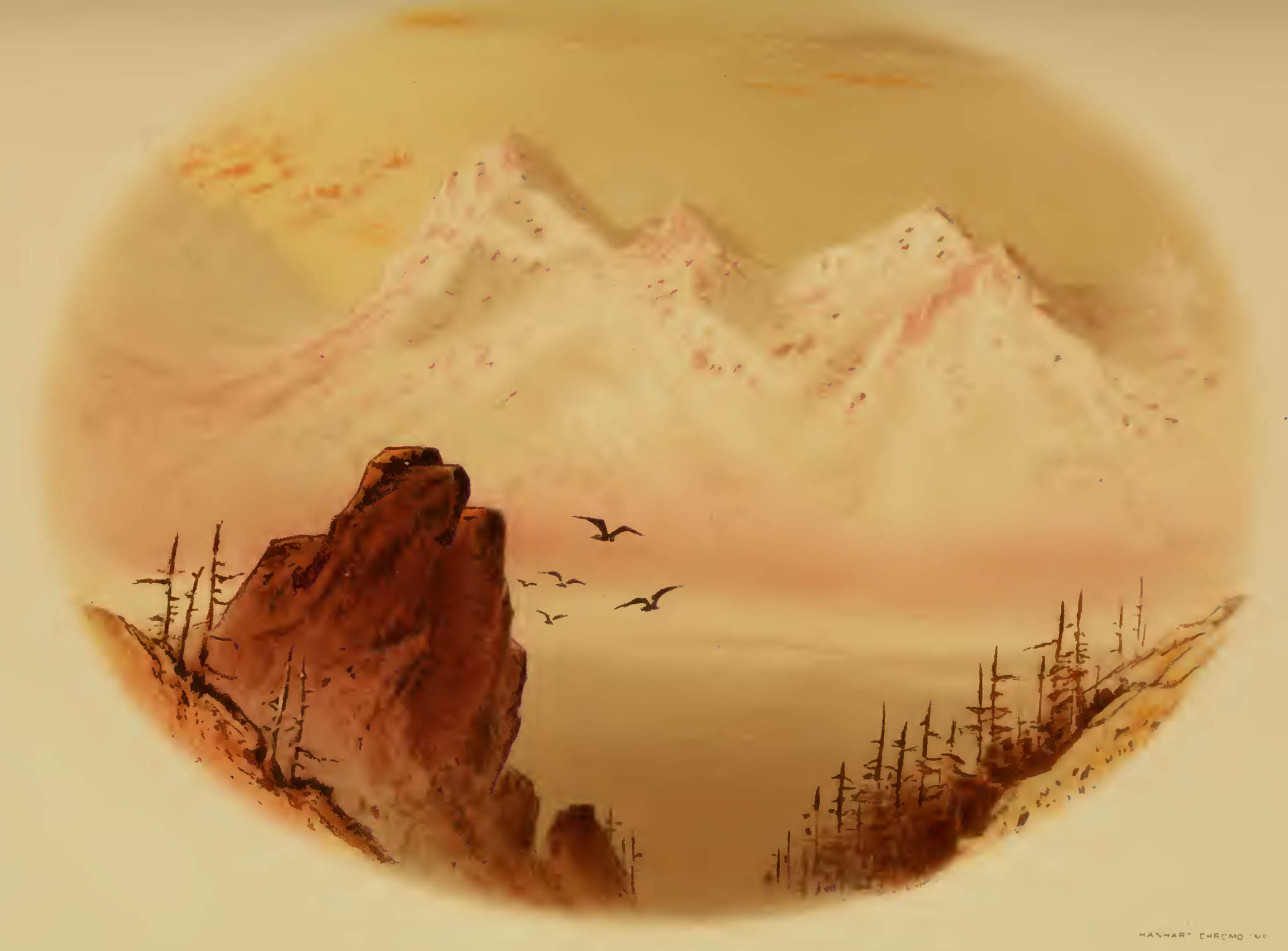

It has been said that nothing can be more grand and majestic than the Alps of Switzerland, and that size is a phantom of the brain, an optical illusion, grandeur consisting rather in form than size. As a rule it may be so; but they are 'minute philosophers' who sometimes argue thus. Not that I would disparage the Swiss Alps, which were my first loves, and which, it must be acknowledged, do possess more of picturesque beauty than the greater, vaster mountains of the East; but the stupendous Himalaya — in their great loneliness and vast magnificence, impossible alike to pen and pencil adequately to pourtray, their height, and depth, and length, and breadth of snow appealing to the emotions — impress one as nothing else can, and seem to expand one's very soul.

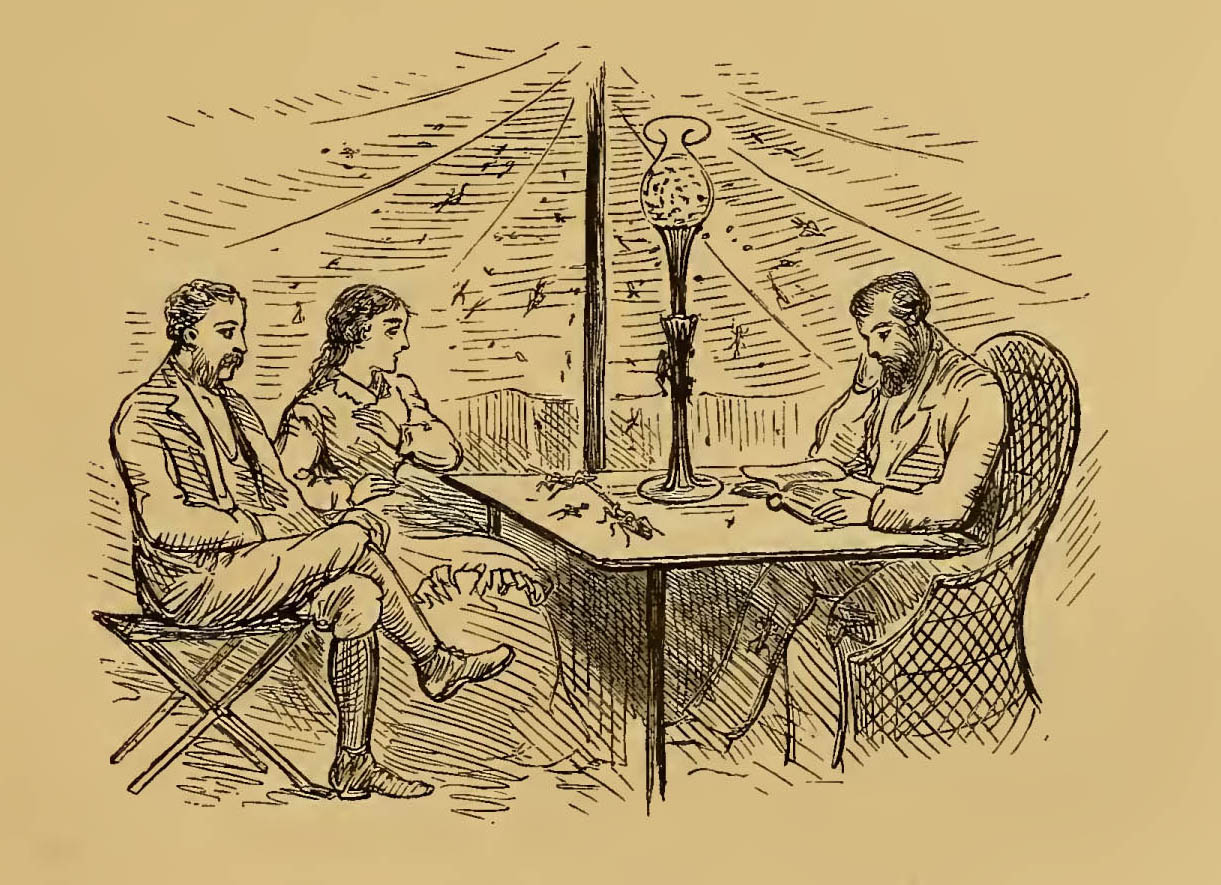

We were sitting at dinner one evening beneath a punkah in one of the cities of the plains of India, feeling languid and flabby and miserable, the thermometer standing at anything you like to mention, when the 'khansamah' (butler) presented F— with a letter, the envelope of which bore the words, 'On Her Majesty's Service;' and on opening it he found himself under orders for two years' service at Darjeeling, one of the lovely settlements in the Himalaya, the 'Abode of Snow' — Him in Sanscrit, signifying 'Snow,' and alaya 'Abode' — the Imaus of the ancients.

Were the 'Powers that be' ever so transcendently gracious? Imagine, if you can, what such an announcement conveyed to our minds. Emancipation from the depleting influences of heat almost unbearable, for the bracing and life-giving breezes which blow over regions of eternal ice and snow.

But even in these days it is wonderful to what an extent ignorance prevails about the more unfrequented parts of India; for it is not generally known, except as a mere abstract truth, that in this vast continent — associated as it is in the purely English mind with scorching heat and arid plains, stretching from horizon to horizon, relieved by naught save belts of palm girt jungle, the habitat of the elephant, the tiger, and the deadly snake — every variety of climate may be found, from the sultry heat and miasma of the tropical valley, to the temperature of the Poles.

Is not India, indeed, almost exclusively regarded as a land of songless birds arrayed in brightest plumage; of gorgeous butterflies and 'atlas' moths; of cacao-nuts, and dates, and pines more luscious than anything of which the classic Pomona could boast? — a land also where snakes sit corkscrew-like at the foot of one's bed, and wild beasts take shelter in one's 'bungalow'; and where her Majesty's liege subjects, whose fate it is to be exiled there, are exposed to the alternate processes of roasting under a tropical sun, and melting beneath a punkah?

To the feminine mind, again, is it not a land of Cashmere shawls — 'such loves' — and fans, and sandalwood boxes, and diaphanous muslins? — presents sent over at too infrequent intervals from uncles and cousins, about whom, vegetating in that far-off land, there is always a halo of pleasant mystery, and arriving, redolent of 'cuscus' and spicy odours and a whole bouquet of Indian fragrance, which wafts one away in spirit across the desert and the sunlit ocean to that wonderland in an instant.

A region there is, however, of countless bright oases in these vast plains, where the cuckoos plaintive note recalls sweet memories of our island home, and mingles with the soft melody of other birds; where the stately oak — monarch of our English woods — spreading its branches, blends them with those of the chestnut, the walnut, and the birch; where in mossy slopes the 'nodding violet blows,' and wild strawberries deck the green bank's side, like rubies set in emerald. I allude of course to the noble snow-capped Himalaya, the loftiest mountains in the world, with whose existence everyone is acquainted, but about which brains even saturated with geographical knowledge are yet as ignorant, so far as their topographical aspect and wondrous hidden beauty are concerned, as they are about the mountains in the moon.

Along this chain, at elevations where the temperature is similar to that of England, numerous sanataria lie nestling, enfolded in their mighty undulations, and dwarfed by the vastness of the surrounding peaks into little toy-like settlements. These are convalescent depôts for our British soldiers, and refuges for Indian society generally; for all who are able migrate from the plains to these cool regions during the fierce heat of summer, to reinvigorate themselves in the delicious climate.

The most beautiful of all these sanataria, as far as scenery is concerned, though by no means the largest, is Darjeeling, or the 'Holy Spot' — the Sceptre of the Priesthood — as its name signifies in the Thibetan language; and to this fair Eden — oh, joy! — we are to proceed without delay.

CHAPTER II.

AWAY TO THE HIGHLANDS!

AND so it came to pass one stifling evening, the sun setting a disc of fire, that two figures might be seen, not descending a hill on 'white palfries,' but stepping into a prosaic 'dinghy,' to be ferried across the Hooghly, a branch of the Ganges — a muddy river truly, but all a-glow now with the sun's crimson dye, which has kindled the dome of Government House and the many cupolas and spires of the fair City of Palaces almost into a blaze.

Away down the river noble ships ride at anchor, waiting for the morrow's tide to bear them over its treacherous and ever-shifting sandbanks to the distant sea. Looking towards the city, forests of stately masts from every port under heaven tower skywards, and along the Strand a dense throng of carriages may be seen moving slowly, as the denizens of the proud metropolis, released from their closed houses — from which every particle of the outer atmosphere has been excluded throughout the livelong day — take their 'hawā khanā,' which, literally translated, means 'eat the air.' From the beautiful 'Eden Gardens' the sound of the band, borne on the sultry breeze, comes wafted towards us; while at the many 'ghauts' numerous figures are seen standing on the steps or in the sacred waters, salaaming to the Day-god as he sinks to rest. Bathing is a religious ceremony with these children of the East — a process said to wash away sin; but, as a rule, they economise time by cleansing their linen and their consciences together, and may generally be seen alternately salaaming and scrubbing away at their 'chuddahs' as they stand waist-deep in the mystic flood.

Noisily settling themselves to roost in the tall pepūl trees that fringe its margin, are enormous bald-headed adjutants; whilst others still linger about the steps, balancing themselves on one leg, their long pouches dangling in the air, as they gravely watch the proceedings of the bathers. Loathsome vultures flutter uneasily 'neath the palm fronds, uttering every now and then a shrill moan, as though possessed with the unquiet spirit of the Hindoo which but a day or two ago tenanted the body they have just left, stranded somewhere down the rivers banks. From the jungle a mile or two away comes the wild jackals cry, answered by another herd more distant still, as they call each other to some unholy feast. The Mahomedans bury their dead, but there was a time, not so long ago either, when the bodies of the 'mild Hindoo,' except those of high caste, were invariably thrown into the river: but cremation of some sort is now, I believe, the custom amongst Hindoos, if not actually enforced by law, although frequent evasions of it still exist

In the days I speak of, the statement that the living were left on the banks to die or be washed away by the tide was no Eastern fable, for I have myself often seen the sick carried along on 'charpoys' (bedsteads) in the direction of the sacred river, moving as they went

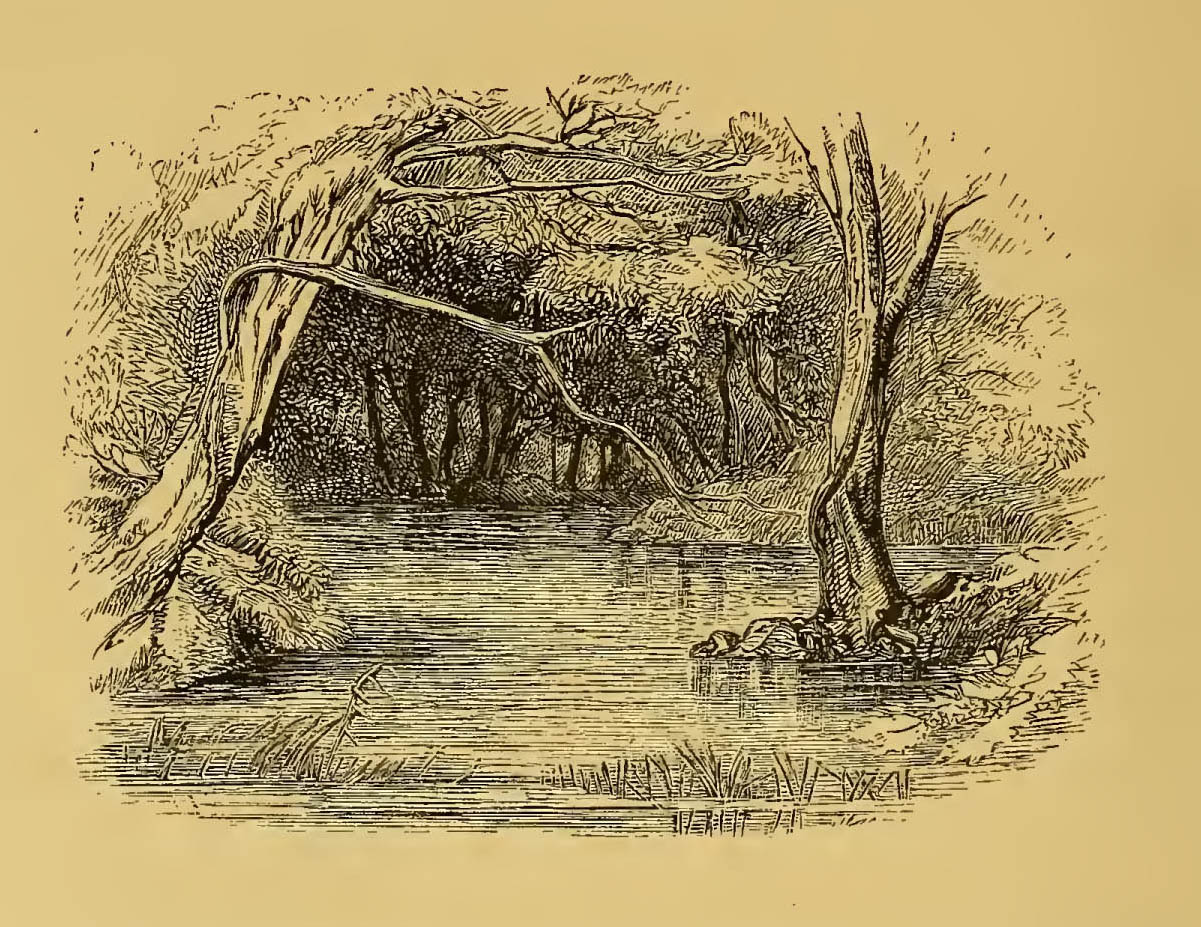

But let us quit such painful scenes. Already merrily gleam the thousand lamps which surround the white palaces of the King of Oude's zananas, like a necklace of diamonds, casting their reflection in the water. In little inlets — arms of the river — all amongst the dark trees, fires are burning, indicating the existence of boats moored there, in which swarthy boatmen are cooking their evening meal. Here and there a tiny light may be seen floating down the river; and you may be sure, though you cannot see them in the gathering darkness, that rustic houris — whose beehive dwellings are hidden in the thick jungle — are standing or kneeling on the slimy brink, watching with eager prayerful eyes the fortunes of the little bark; for these superstitious people seek therefrom the foreknowledge of events. If it float on out of sight still burning, well is it for the object of their wishes; but should it go out — by no means unfrequently the case — the contrary is augured. These lights, floating star-like on the dark waters, and seen from the suburban bridges at all hours of the night, are to my mind the one poetical feature of this eastern city.

Ferried across to the measure of our boatmen's 'barcarolle,' we reach the opposite shore just as the steam-ferry draws up to the pier; and there is no time to lose, for the express is waiting its arrival.

'Can't get in there, sir; that is reserved accommodation for ladies,' shouts the station-master from the other end of the platform, on F—'s following me into the luxurious first-class carriage, fitted with berths for night travelling. As there happens to be no other lady passenger, however, he is permitted to remain; and to prevent molestation at either of the subsequent stations, he at once lies down, and covering himself with shawls and other articles of feminine attire, hopes thus to elude detection.

Leaving all signs of the great metropolis behind, we are soon whirling through rural Bengal: and what a deadly looking swamp it is! Through rice fields, stretching away into the distant horizon; by morass, and fen, and sedgy pool, till the whole country seems under water; by clumps of waving palm trees, standing out black against the afterglow like funereal plumes; till evening at length gives place to night, and all colour fades save in the West, where a narrow blood-red streak, like the reflection from a hundred monster furnaces, still lingers in the heavens, and we reach Serampore.

The official looks in, apparently regarding the lanky figure opposite me with some suspicion. He is no doubt up to these little subterfuges, but he passes by notwithstanding; and I have just made up my mind that we are to be left undisturbed, when he returns, and this time stands upon the step and looks in.

'Is that a lady opposite you?' he enquires.

'A lady? Well, no; not exactly! The fact is, it is my husband,' I am obliged to confess at last, as F—, moving slightly, lets the shawl slip with which I had endeavoured to conceal him, thereby betraying an unmistakably masculine boot.

'Then you must come out of this carriage, sir.'

'I can't,' replies F—, with some degree of truth; 'my wife's an invalid, and I cannot leave her.'

'Can't help that, sir,' rejoins the uncompromising station-master. 'There's a carriage here, where you can both travel together' (holding the door of one of the general first-class carriages open).

At this juncture, having heard the altercation, the guard appeared, and, master of the situation, addressing F— with a significant look, said: 'Come into this carriage, sir;' and aside, 'I'll make it all right at the next station.'

Upon which F— retired for the present, soon to return in triumph for the remainder of the night, when he subsided into sound sleep till peep of day, by which time we reached Sahibgunge, and our railway journey was completed.

Here we were told by an oleaginous native functionary, who gave us the information as though it were a matter of no consequence whatever — which nothing ever seems to be to these phlegmatic people — that all our baggage had been left behind, adding that a luggage train left an hour or two after the express, by which he thought it likely they might forward it, in which case we should get it in the course of the day. At this announcement F— growled out something that I did not catch; perhaps it was a benediction, perhaps it was not. At any rate, it was already too hot to think of getting into a passion; for, early as it was, the sun had sent upwards his avant-guard of crimson cloud, bearing, as on ensign armorial, all the blazonry of his pomp and splendour, and a curtain, like cloth of gold, suddenly spread itself over the Eastern sky, as it does only in these latitudes.

Now this non-arrival of our effects would have obliged us to stay at Sahibgunge all the next day — one of the most execrable places in the Mofussil of India — had we not brought a trustworthy servant with us, the steamer by which we were to cross to Caragola leaving hours before the baggage-train would be due. But we are able to depart, fortunately, committing our belongings to his charge, and leaving him to wait their arrival, and follow with them the next day.

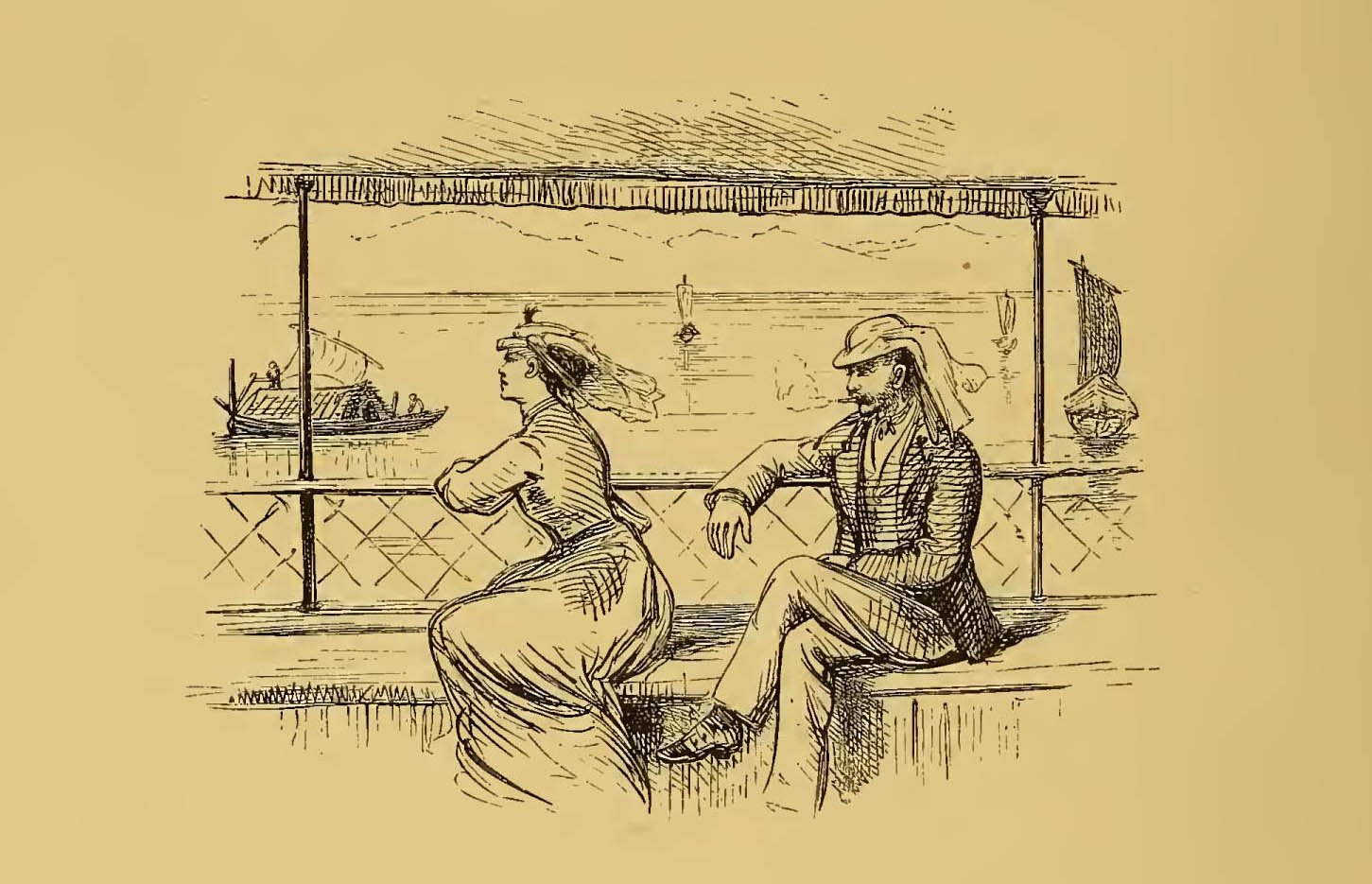

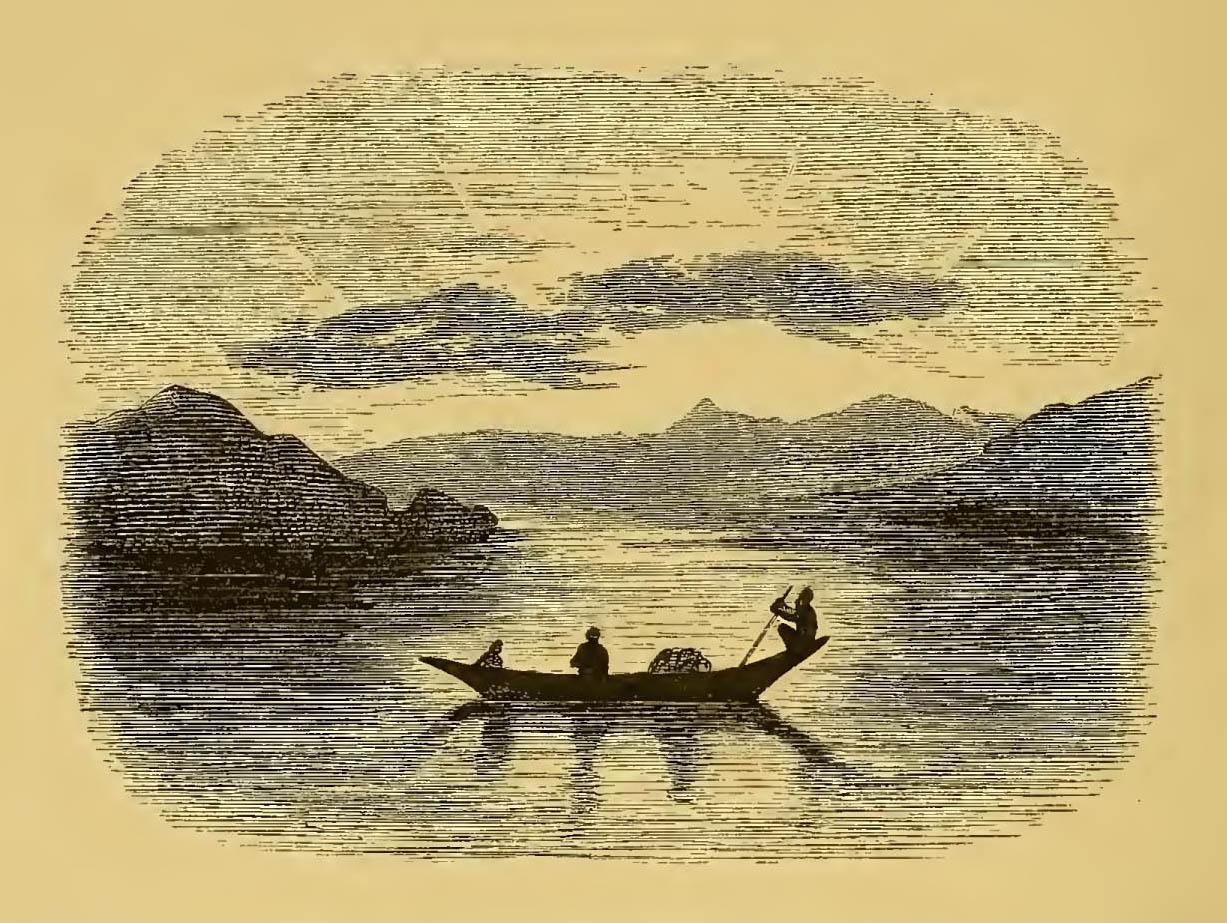

The sacred river from this point looks like a broad lake, with low sand-banks here and there, like little flat islands, just peeping above the water. Reaching the Steamer, we find that, being the only passengers, we are to have it all to ourselves; and at ten o'clock, casting off her moorings, we are afloat for the first time upon the sacred Ganges.

Sitting under the awning we watch the various boats float by: some like immense hay-stacks rowed by twenty men; others with clumsy square sails, and thatched huts on their decks, containing merchandise from Nepaul; whilst light little dinghies, with sails set to the wind, bob up and down as they get into the swell of the steamer, and seem to be curtseying to us as they pass.

Then leaning over the steamer's side, I fancy I travel onwards far far away along the course of this mighty stream, even to its birthplace in eternal snow, whence, issuing beneath a low arch among the glaciers, it is first seen trickling over its narrow bed, worn deep in solid granite, at so great an elevation that the more ignorant of its worshippers believe it descends from paradise itself. Amongst a people of so lively an imagination and extravagant sentiment, endowing as they do so many things inanimate with form and life, it is no wonder that they should have idealised that which brings with it, as from the very heavens, not only fertilisation to these parching plains, but so many other blessings. Accordingly there is a whole world of fables believed in by Hindoos concerning this holiest of rivers, with which the most ancient of all classic lore is connected, and they worship it under the imagery of a goddess whom they call Gunga, the daughter of Himavat; the sublime and lofty solitudes of the Himalaya, like Mount Olympus to the Greeks, being the very home and centre of their mythology. The Hindoos were in a high state of civilisation when Europe was still lying in deepest slumber; for it must be remembered that Hindustan was the cradle of the arts and sciences, and these people — 'Niggers,' as I have often heard them contemptuously called — were in possession of both, when even the Greeks lay in obscurity, and the Britons, too oft their despisers, were — humiliating thought — barbarians!

When the sun gets vertical, the captain kindly places his cabin at my disposal — the only one in the steamer — where, weary of my night's travelling, I remain till it begins to set behind the crimson horizon. And what a sunset! turning the fleet of little boats moored along its banks — for we are gradually nearing Caragola — into jewelled caskets. Far out in the stream a boat is crossing the sunlight, looking black and weird, with a man sitting at its prow, who, for aught that he looked like, might have been Charon himself, ferrying the spirits of the departed over Styx.

Dinner is provided on board, after which we again go on deck, and see the moon rise, a full round orb, bridging the river by a band of tremulous silver light. Southwards the bold outline of the Rajmahals is seen, quite respectable hills, which by courtesy one might almost call mountains, after living long in the plains. They cast a reflection deep and sombre on the broad expanse of water, in the shadow of which a ship is anchored — a mere toy it looks from this distance, its solitary light burning pale and cold. A flight of wild ducks skims past us, and over the still waters comes softly a boatman's song, 'La — illa — illa — la,' rising and falling in musical but pathetic cadence.

CHAPTER III.

'THE GOVERNMENT BULLOCK TRAIN.'

AND now, how can I describe the old-world style of locomotion, still existing in the nineteenth century, on the 'Grand Trunk Road' in this magnificent Dependency, 'the brightest jewel,' &c. &c., for we have reached a shore where the shriek of the locomotive is never heard.

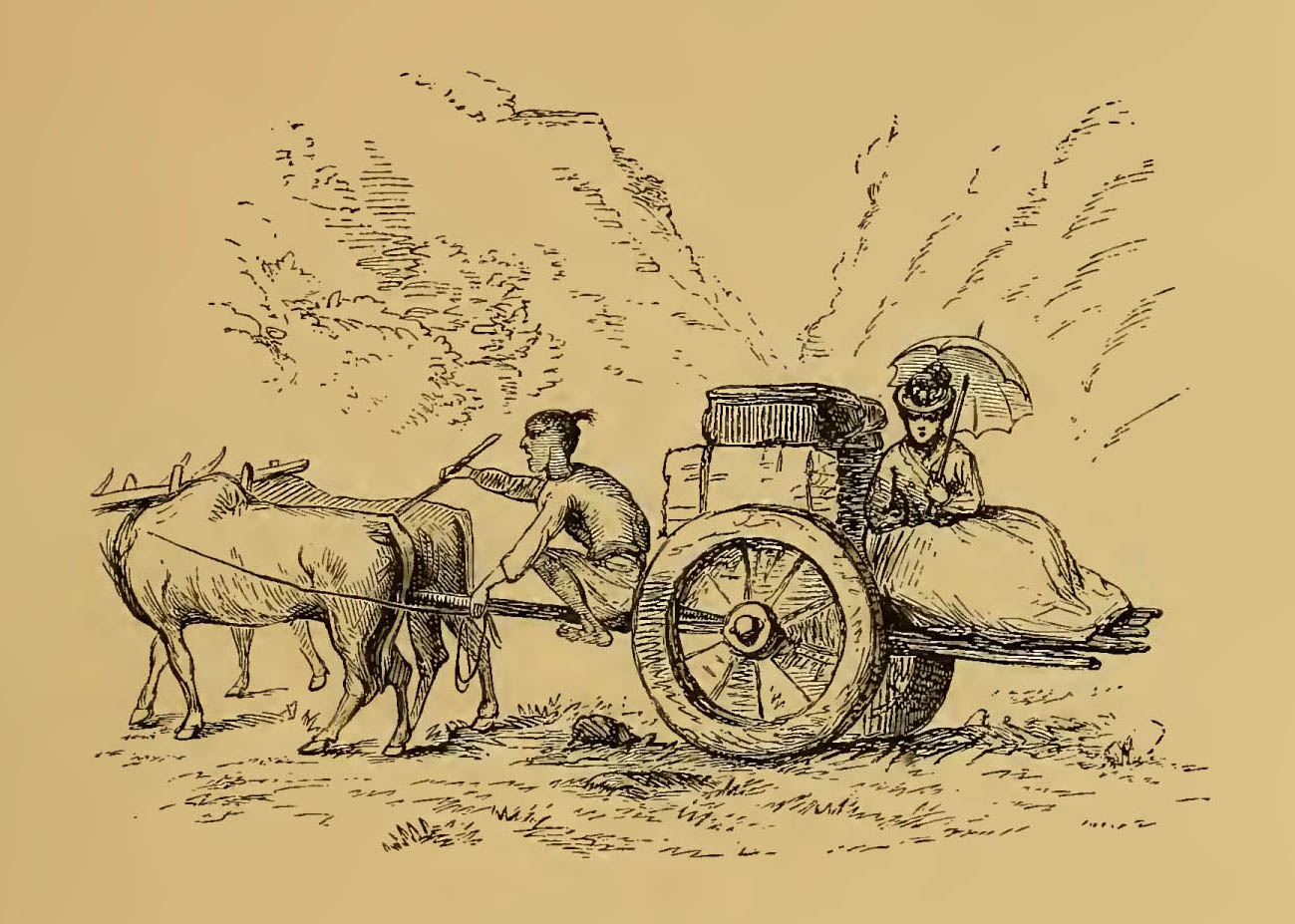

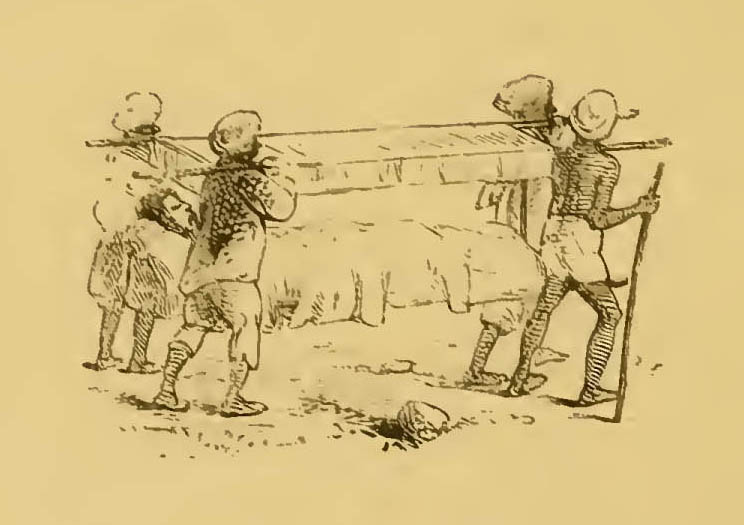

Having left the steamer on our arrival at Caragola, and crawling up the steep incline knee-deep in sand, we find a 'hackery' awaiting us, covered by a rough tilt — a sort of gipsy arrangement — to which are yoked two small bullocks; the whole thing of a kind which you feel sure must have been in use in the time of the Pharaohs, the wheels of almost solid wood rolling round with a reluctance and squeak that is positively maddening. This goes, laughable as it may seem, by the dignified and euphonious appellation of the 'Government Bullock Train.'

All is ready for departure, for they had seen the steamer, a little black speck in the horizon, two hours ago. We mount our chariot therefore and start at the magnificient pace of a mile and a half an hour. The rules are, I believe, that they shall not be required to go faster than three miles an hour; but as they, never by any chance arrive at this alarming speed, the prohibition is scarcely necessary.

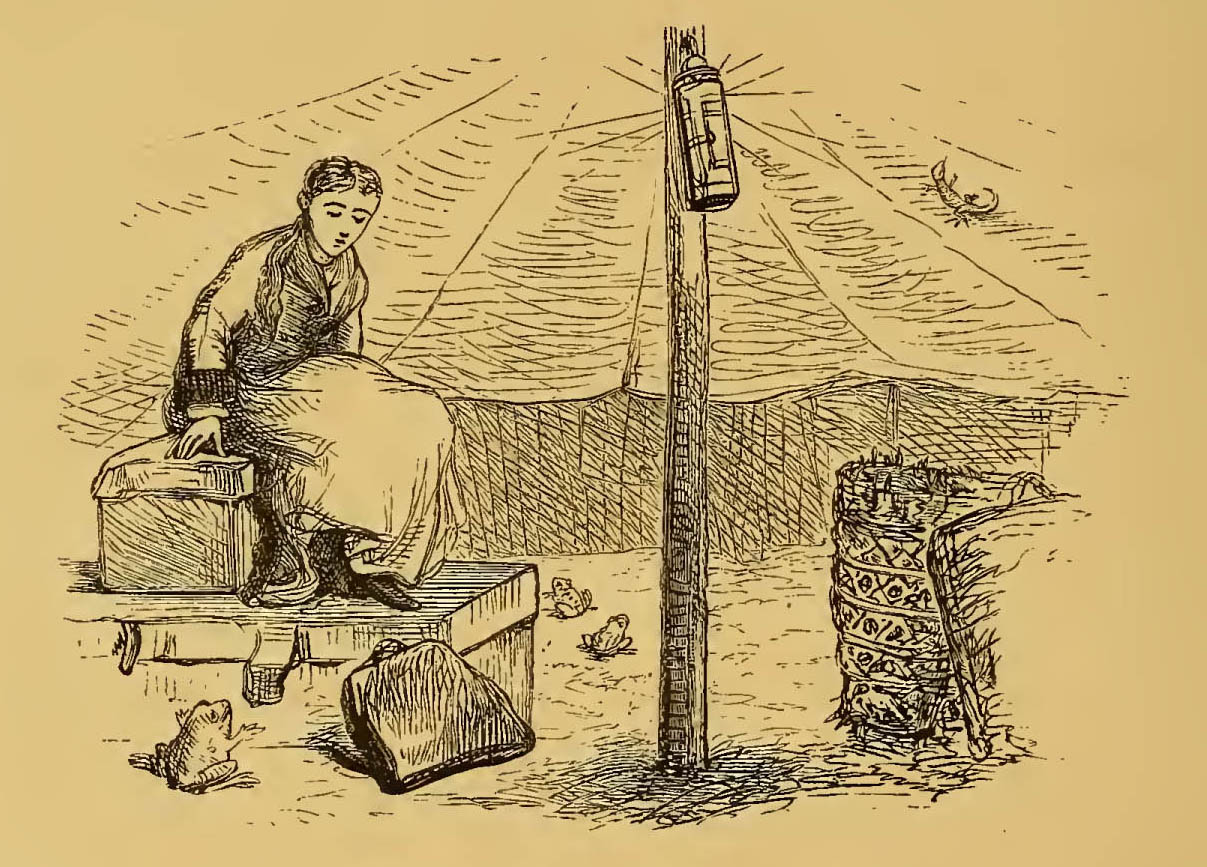

A lantern suspended from the tilt sways to and fro, the tassel of F—'s smoking-cap, doing likewise, keeps time with it; the body of the driver, sitting astride the pole to which the bullocks are attached, sways backwards and forwards too, with the regularity of a piece of mechanism, as he pokes and pushes first this bullock and then that, varied only, alas! by screwing their tails round and round in his endeavours to get them on. Besides this, the goad, a short stout stick, is often called into requisition, answering the double purpose of poking and striking, the latter accomplished in successive thuds on their poor lean backs, and accompanied by an amount of jabbering persuasion inconceivable to anyone who has not travelled under the Jehuship of an Asiatic, the former making one's very heart sick, and the latter beyond everything annoying to the ear. But nothing makes the slightest impression upon them. By all these combined efforts they are simply kept in motion, and I soon grow stoical in the matter, and learn to believe that without them they would not move at all.

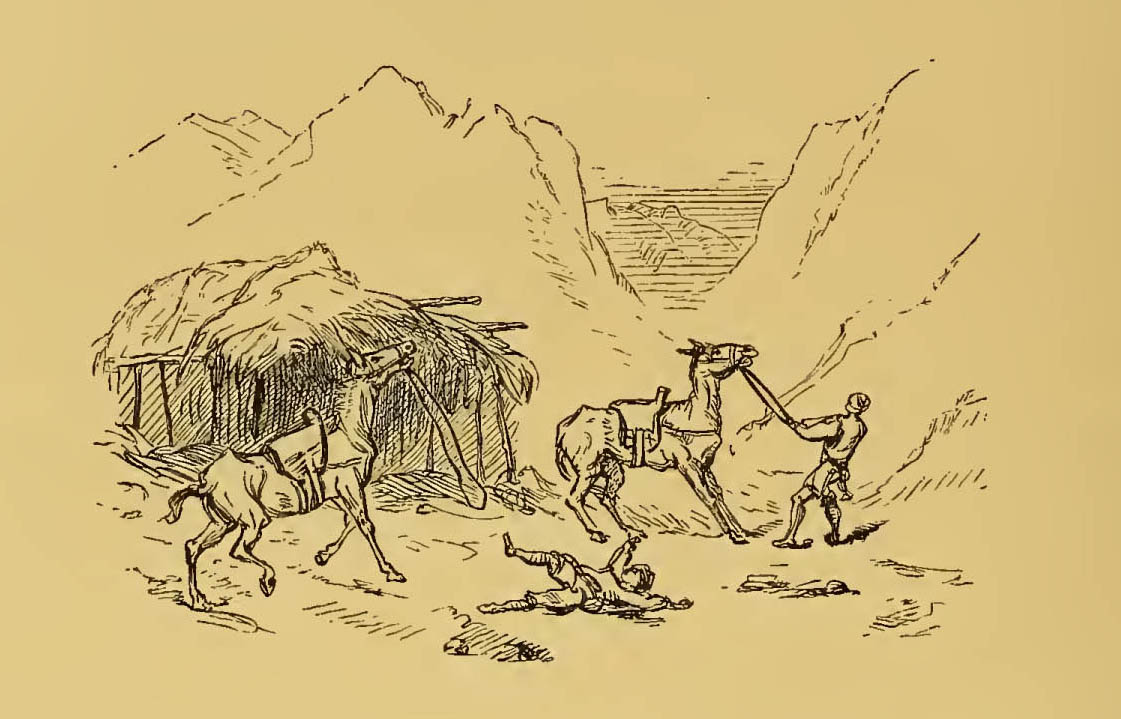

After a while, however, just when we are sinking into a state of somnolence, induced by the monotony of the whole performance, we hear the stick administered with more than ordinary energy, and they do make an effort for once, and succeed in getting into a trot; but it is only to take us clean off the road and land us upside-down in the 'paddy' (rice) field seven feet below.

But this does not appear to excite the smallest surprise in our Jehu, who seems to take it all as a matter of course; and after we have managed to scramble out — hardly knowing which is our head or which our heels, not hurt, but severely shaken — he gives them one deprecatory glance, and proceeds leisurely to unfasten the yoke.

The bullocks, once loose, begin quietly grazing as if nothing had happened, whilst we sit down on the bank and bear it as philosophically as we can, till our triumphal car is righted and again put in motion, when, in process of time, we reach the first 'chokee' (or stage), and have to change our noble beasts.

This is a sleepy little village, surrounded by 'paddy' fields, a light here and there glimmering feebly through the doors of the mud huts. The driver shouts, to arouse the amiable native who has to furnish us with the expected relay. 'Jaf-fa!' repeated several times, but no answer; 'Ho! Jaf-fa-a-a-a!' descending the gamut in an injured tone. At length a light is seen slowly approaching from a distant hut — they never hurry themselves, these Orientals, under the most pressing circumstances — and the bearer of it gives us the consoling information that there is no relay of bullocks, a 'bobbery (quarrelsome) sahib' having taken those we were to have had for his own 'dâk' about an hour ago, his beasts having broken down by the way.

At this declaration, the driver makes use of choice Hindustani expletives, and pronounces it to be a 'jhūt' (lie); but on his maintaining the assertion, what can we do but 'bless the bobbery sahib,' which I am afraid F— does in language no less complimentary, and offer 'backsheesh' to our informant if he will only obtain other bullocks speedily elsewhere.

Stimulated by this magic word, he retires with more precipitation than is their wont, and we watch his light growing fainter and fainter as he crosses the paddy-field. No matter how bright may shine the moon, natives are never seen without carrying a lantern at night, which they say frightens away 'cobras,' a snake whose bite is death; and presently we hear his voice growing more and more distant, as he calls his kine, straying in the jungle far away; whilst we are compelled to wait two weary, dreary, miserable hours, before we can once more proceed on our way.

This, then, is the 'Government Bullock Train' — what an imposing title! — for which, together with the transit of our luggage by a similar conveyance, F—, with becoming gravity, paid 75 rupees (7l. 10s.) to the Post-office authorities a few days before starting, the name in itself being a guarantee of its respectability, suggesting to the mind of the uninitiated, if it suggested anything in particular, a train freighted with bullocks! At any rate the word train at once conveyed the idea of speed, and for this reason it has no doubt been ironically given; but we hope the Indian Government will be more sedate in its nomenclature for the future, and give up jesting, which is improper and undignified in the Great.

In like fashion creeping along the road, the monotony relieved by similar incidents, the first faint streak of dawn appears, and in the cold grey half-light we overtake long lines of 'hackeries' of a more primitive kind than that even in which we are journeying, each wheel, as it revolves, producing its own particular and peculiar squeak — for they never grease them, to do so would cause the drivers to lose their caste — all looking as if they had come straight out of the land of Canaan, and were going down into Egypt to buy oil, and corn, and wine; and, following in their wake, we fancy we must be going down into Egypt too, with our money in our sack's mouth.

Past miles and miles of dusty pepūl trees, growing on each side of the road, the soft blue distance seen through them, bathed in silvery mist, and there is a dewy freshness in the air. Past strings of pilgrims, walking wearily along to or from some shrine, probably Parisnāth, a mountain of unusual sanctity across the Ganges, the centre of Jain worship. On, till we meet commissariat waggons, drawn by immense bullocks, beautiful creatures with large meek eyes like gazelles, soft dove-colour skins, and large humps on their backs, which, being hungry, we feel inclined to eat, there being nothing carnose half so delicious as these humps when salted. Past little villages, scarcely awake yet, and more hackeries, the poor beasts moving their heads from side to side, as they strive to make the hard yoke easier to their necks. Ah! well, indeed, has Scripture used it as a symbol of a burden grievous to be borne.

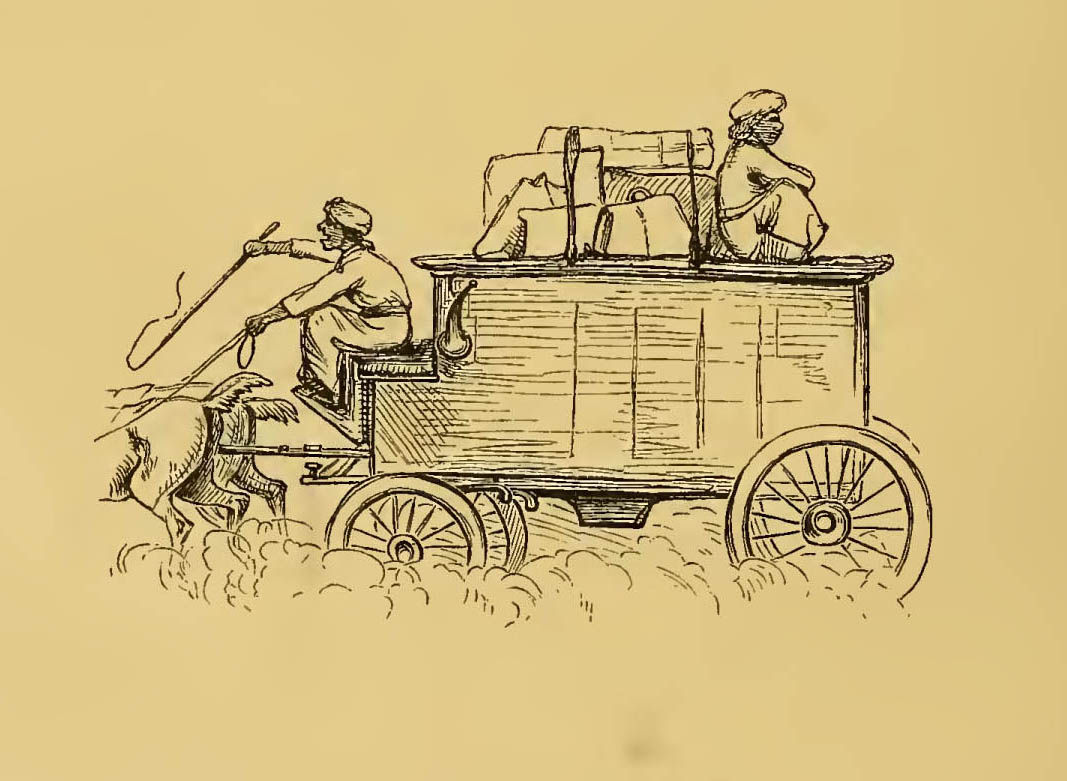

At length a great clatter is heard in the distance, and something is seen hovering above the road, bearing down upon us like an enormous vulture, which turns out to be nothing more or less than Her Majesty's mail, sending up clouds of dust, and hiding everything but the driver and an unhappy traveller clinging on by his eyelids to the back seat.

CHAPTER IV.

WE REACH OUR FIRST STAGING BUNGALOW, AND PARTAKE OF 'SUDDEN DEATH.'

IT was broad day by the time we reached Purneah, and came to anchor in the little 'bungalow' which answers to a roadside inn. We caught sight of the kitmutgar, or table attendant, some little time ago, performing his simple toilet in the verandah, as he heard the familiar squeak of our chariot wheels, and knew that some 'sahib logue' must be approaching. We have scarcely alighted when he presents himself, and with a low salaam begs to be informed what we wish for breakfast, which is followed by the very natural question from the 'sahib logue' of 'What can you give us?' — the rejoinder, nine times out of ten in these places, where travellers are comparatively few and far between, being, 'Moorghee grill, sahib, aur chupattee (grilled fowl and chupattee):' the former, a dish known in India, in the language of modern ethics, as 'sudden death,' from the fact of the unfortunate little feathered biped being captured, killed, skinned, grilled, and on the table in the space of twenty minutes; and the latter an odious leathery, and indigestible compound, apparently made of equal proportions of sand and flour, and eaten as a substitute for bread.

Now follows the chase for the irrepressible 'moorghee,' which is always at hand, pecking and strutting about amongst its kind in the 'compound,' or inclosure of the bungalow; sometimes making migratory raids and explorations into the hackery in search of crumbs, or any other small delicacies that may happen to be found within it, till the bāwārchi (cook) is seen emerging from the cookhouse across the yard, at the sight of whom, even before he is in pursuit, the whole brood are in violent commotion, their instinct — or 'hereditary experience,' handed down to them by a long line of suffering ancestors, likewise sacrificed to 'grill' — warning them what is to come. The greater number, however, manage to elude the inevitable for a while, by making their escape; but one or two of nervous temperament get too frightened to follow the rest in their flight, and, losing their heads entirely, make a dash into the bungalow itself, then under the table, and, hunted down for a few minutes longer, are usually run to earth at last beneath one's very chair. Then succeeds the poor little captive's last speech and confession, whilst the kitmutgar is hastily laying the cloth, and one can hear it frizzling over the fire in a twinkling. Should the traveller require a second or third course, as he generally does, moorghee cutlets or moorghee currie await him; and other victims have to be sacrificed, accompanied by the usual preliminaries.

Here, however, we find ourselves in clover, and in the lap of luxury itself, for Purneah being a station of some importance, it possesses a bazaar, and the kitmutgar informs us that, in addition to 'moorghee grill,' we can have 'mutton chop grid-iron-fry,' whatever that may be — a dish hitherto unknown to us in our experience of the deep mysteries of the Indian cuisine.

These staging bungalows usually contain four rooms, each opening pleasantly upon a verandah; the furniture, however, is of the most wretched description, consisting merely of a table, a punkah, and a few uncomfortable chairs, in which, after your long journey, you sit ill at ease, wishing you possessed the buckram vertebræ of your ancestors, whilst the matting covering the floors is too frequently in holes. Musing as you sit bolt upright, you will probably be attracted by the least possible noise, and, on looking in the direction of the sound, may see a pair of antennæ or tiny legs, with a small head peeping above the matting where it skirts the walls. It may be that of a centipede or little black scorpion, or, if the time be evening, a fleshy-brown cockroach. They are as a rule, however, very clean, being under the superintendence of the Public Works Department — not the cockroaches, but the bungalows — and are unquestionably a great convenience to travellers up the country.

Weary of our long night in the 'Government Bullock Train' — I wish with all my heart the members of the 'Supreme Government' were obliged to travel in it for fifteen consecutive hours! — we hire a 'palkee gharee' to take us on to the next station, Sileegoree, deciding to halt where we are during the day, and to proceed on our journey in the cool of the evening. Accordingly at 6 P.M. an oblong deadly-looking machine, resembling a hearse, makes its appearance, drawn by two horses, the pace whereof is guaranteed to be ten miles an hour, when once they have been persuaded to make a start!

To our inexpressible relief our servant arrived some hours ago, bringing with him our long-lost luggage, and whilst it is being packed on the top, the horses are taken out, something being amiss with the harness. One of them is a sturdy little animal, the other a tall bony creature, with a neck like a giraffe, of the genus Bucephalus Alexandrinus, with a great deal of 'spirit' in him, judging from his proud exterior, and the way he carries his head; but we soon find, alas! that this quality resides in his outward bearing only. During the process of harnessing, which proceeds with no small difficulty, requested by the coachman to take our places, we get in, and lie down side by side at full length, that being the appropriate mode of conveyance.

Six men seize the wheels, crack goes the whip, 'Whr-r-r-r-r!' shouts the coachman, simultaneously; Bucephalus assumes a war-like attitude, raises his head haughtily, and paws the air. The smaller animal pulls conscientiously, but still we do not move. The coachman performs a feat, not only of arms but legs, throwing both over his head in utter desperation. Another crack of the whip, and Bucephalus this time backs determinedly, threatening to overturn us into a dirty pond hard by.

Chorus of men still at the wheels, 'La-la-hi-hi-iddl-iddl-iddl-whish-sh-sh!' The last syllable prolonged and hissed through the teeth. Truly the mouths of these Bengalees seem made especially for the utterance of infinitesimal monosyllables. But they prevail at last, and we are en route. The coachman, or chief undertaker, seizing his bugle, plays a pathetic, 'Too-too-too,' and we go on now at an ever-increasing pace, whilst the vehicle sways from side to side ominously, and we realise in an instant the meaning of the hearse, and feel we are being borne along to a speedy and untimely grave, and so on, and so on, till — as Mr. Pecksniff remarked to his charming daughters, on their way to London —' It is to-morrow, and we are there.'

CHAPTER V.

WE MAKE OUR TRIUMPHAL ENTRY INTO PUNKAHBAREE.

BUT although it is 'to-morrow,' for it is long past midnight, and we are 'there,' that does not mean Darjeeling, but Kishengunge; and a dismal and ugly place it truly is at this time of night.

Kishengunge, through which the road passes, is a thickly populated village, noted at one time for dacoits; and even now it not unfrequently happens that travellers, on their way to or from the Hills, are molested by these daring highway robbers. Not very long ago a British officer journeying to — was beset by a band of them, and robbed of every stitch of luggage he possessed. Now it happened that, according to the custom of Indian travellers on these long night journeys, he had disencumbered himself of all superfluous attire, and donning his dressing-gown and night-cap, under a happy consciousness of absolute security, he laid him down comfortably, as he thought, till morning. But behold the gallant officer as he appeared on arrival at his destination!

Moral: when travelling by dāk gharee in India, be not over-confident, but go to sleep in complete armour, ready for any emergency.

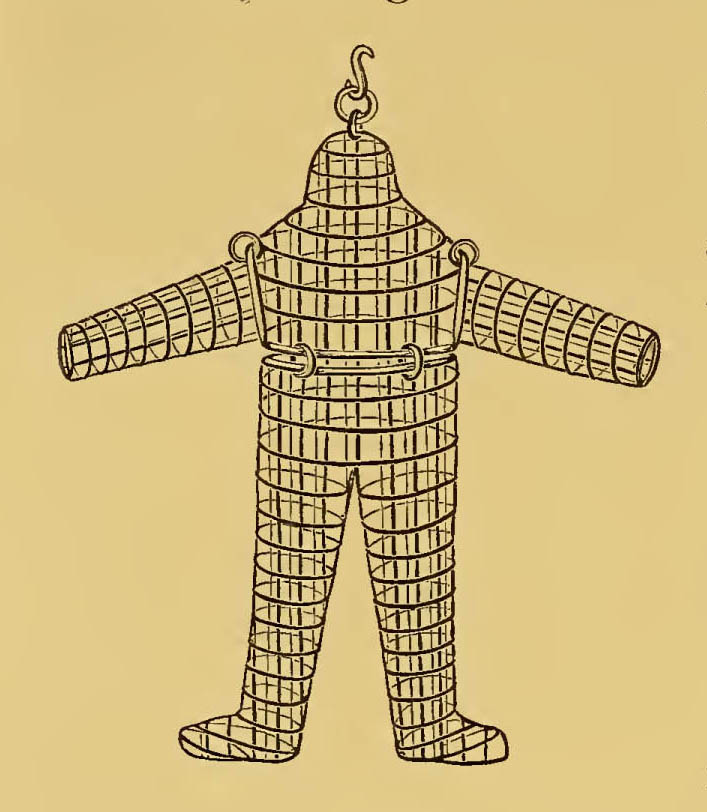

Shortly after the commencement of his Indian career, whilst travelling in Eastern Bengal, F— observed, hanging to a tree, a singular thing in the form of a cross, made of iron hoops, apparently rusty from extreme age and desuetude. On enquiry, he learnt that it was no less than a man-cage, an interesting relic of the past. As far as he could ascertain from local tradition, dacoits were formerly placed in it when captured, and left suspended to a tree by the roadside as a warning to others; but whether they were hung up alive and left to die a lingering death, or after they had been deprived of life, he could gain no satisfactory information: the former, however, is by far the most natural hypothesis.

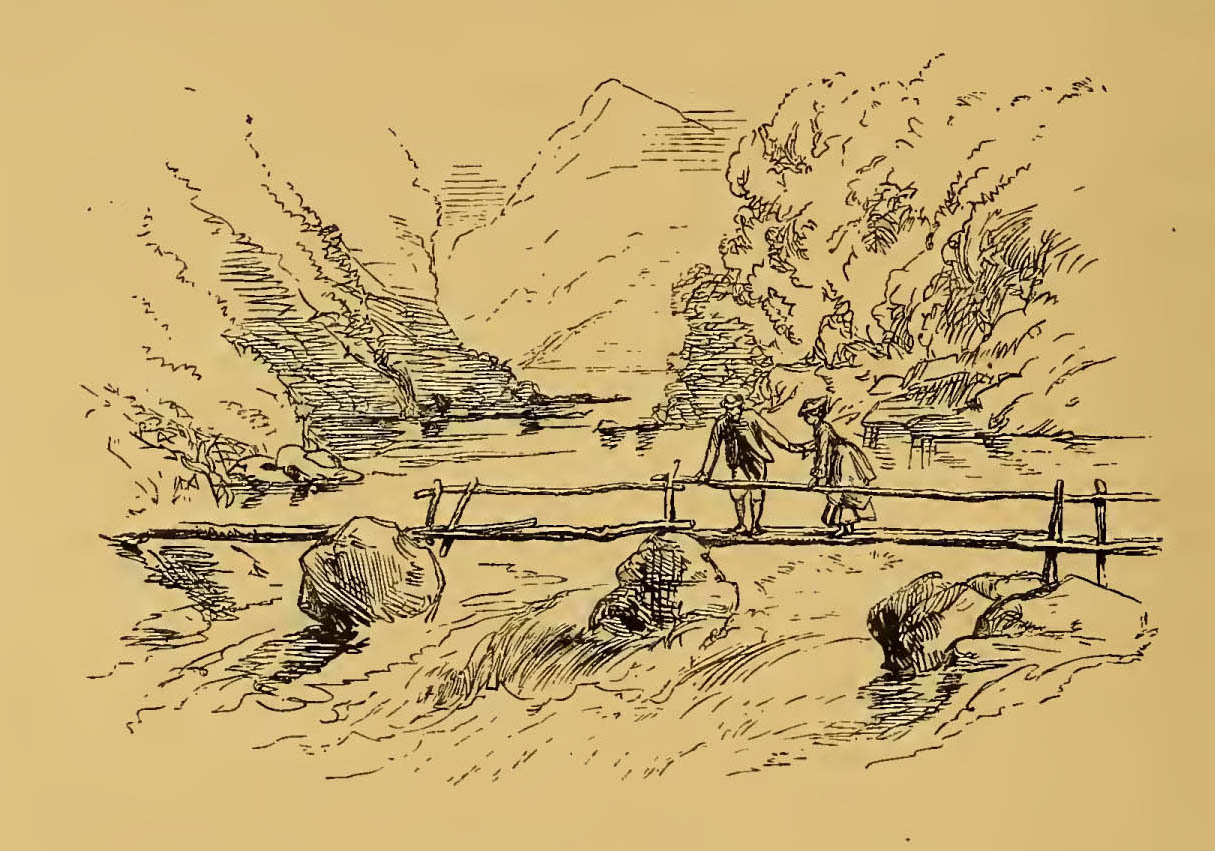

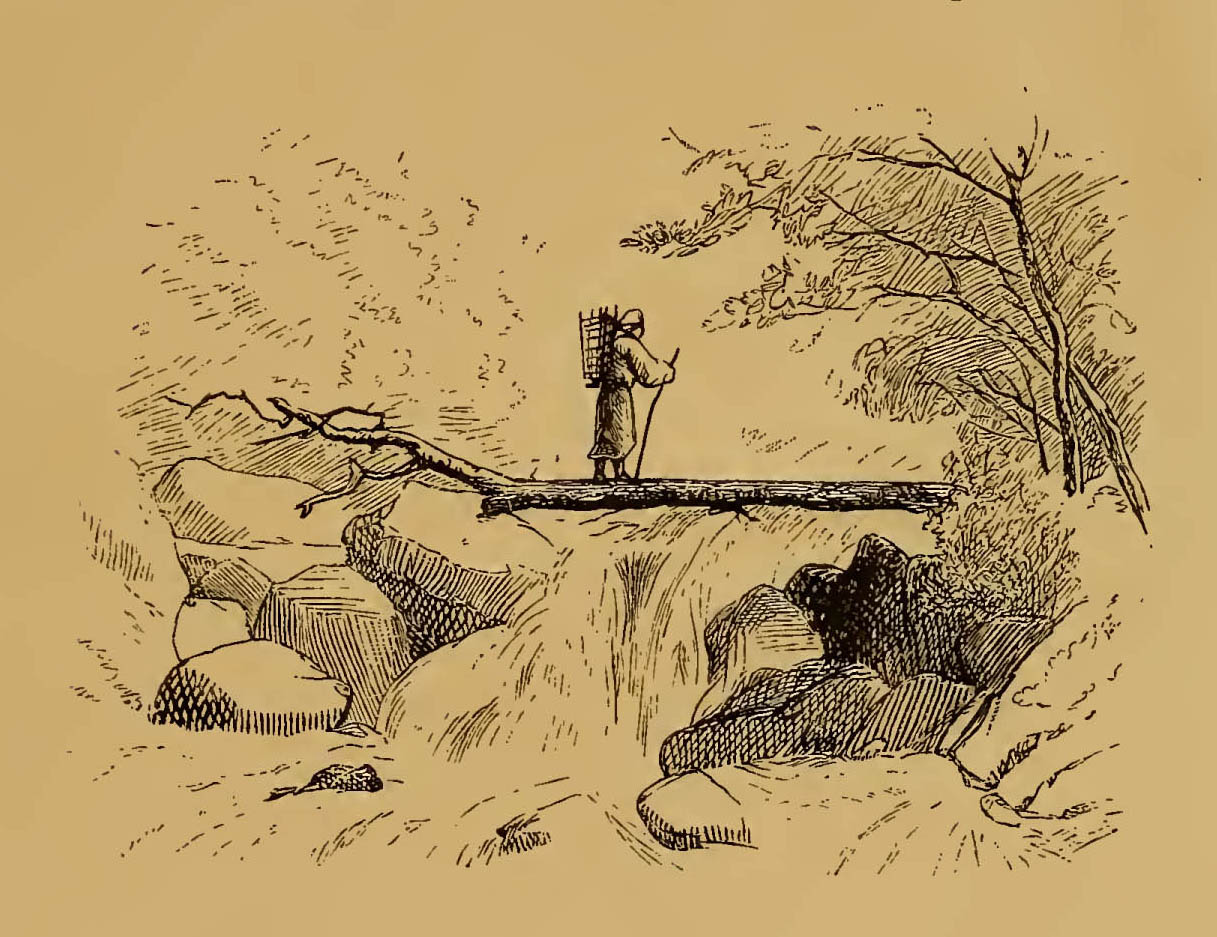

We have now to descend a steep bank to a 'nullah,' or river, sixteen men, awakened by the sounds of the coachman's bugle, being in readiness to assist us, which they do by holding on to ropes attached to the gharee, to prevent its being precipitated too rapidly down the incline; and well is it that we cross the river under cover of darkness, and do not see our ferry — a frail platform of bamboo, placed upon two canoes. But safely arrived on the other side, the same number of men push us up the bank, uttering a chorus of the most unearthly yells, and in process of time we reach the dâk bungalow at Siligoree.

Siligoree lies within a short distance of the foot of the Hills, and close to the malarious Terai — a belt of jungle, where some years ago Lady Canning, the wife of the Governor-General of India at that time, the 'Lily Queen' as she was often appropriately called, caught jungle fever from staying here one night only, on her way from Darjeeling, and soon afterwards died at Calcutta.

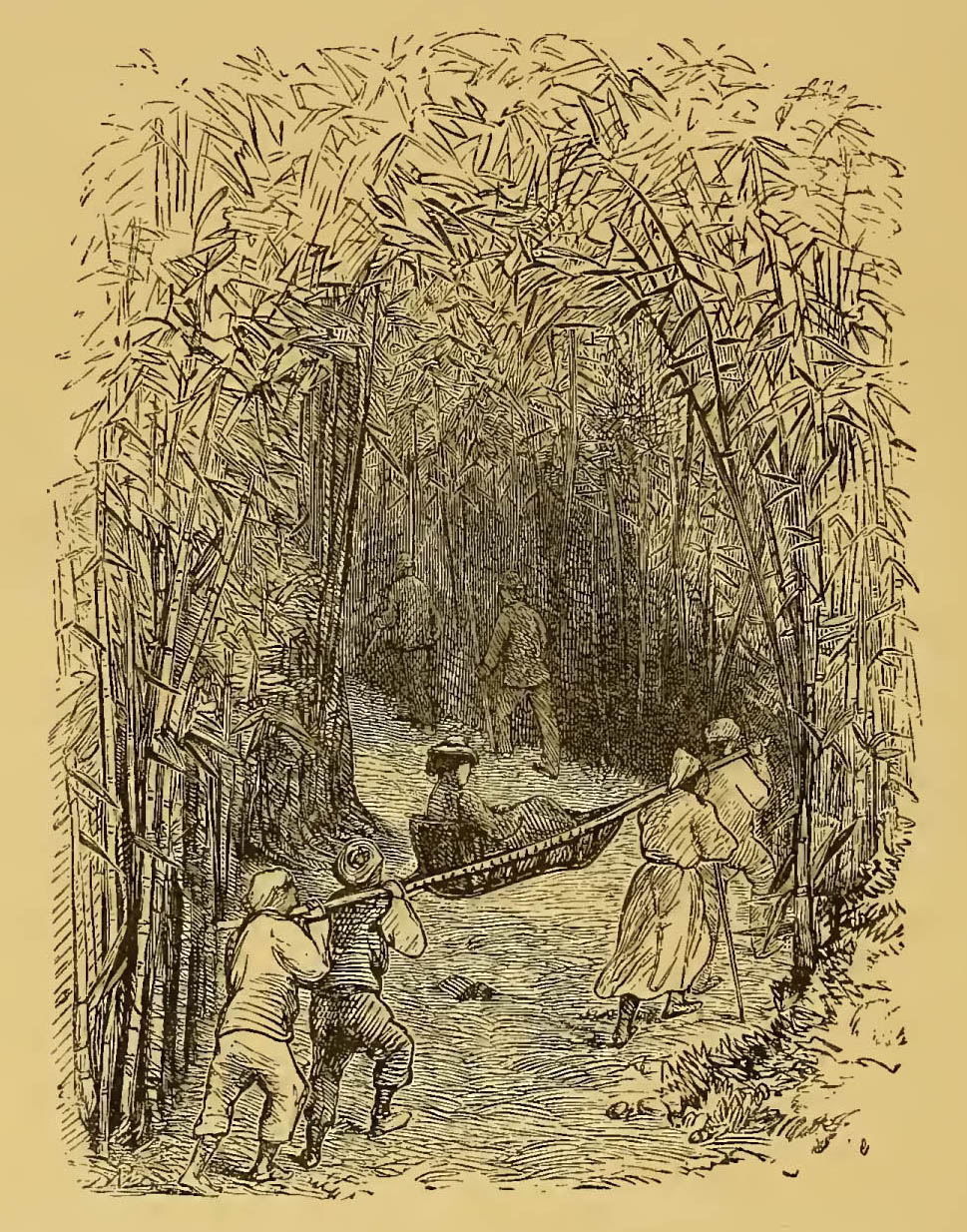

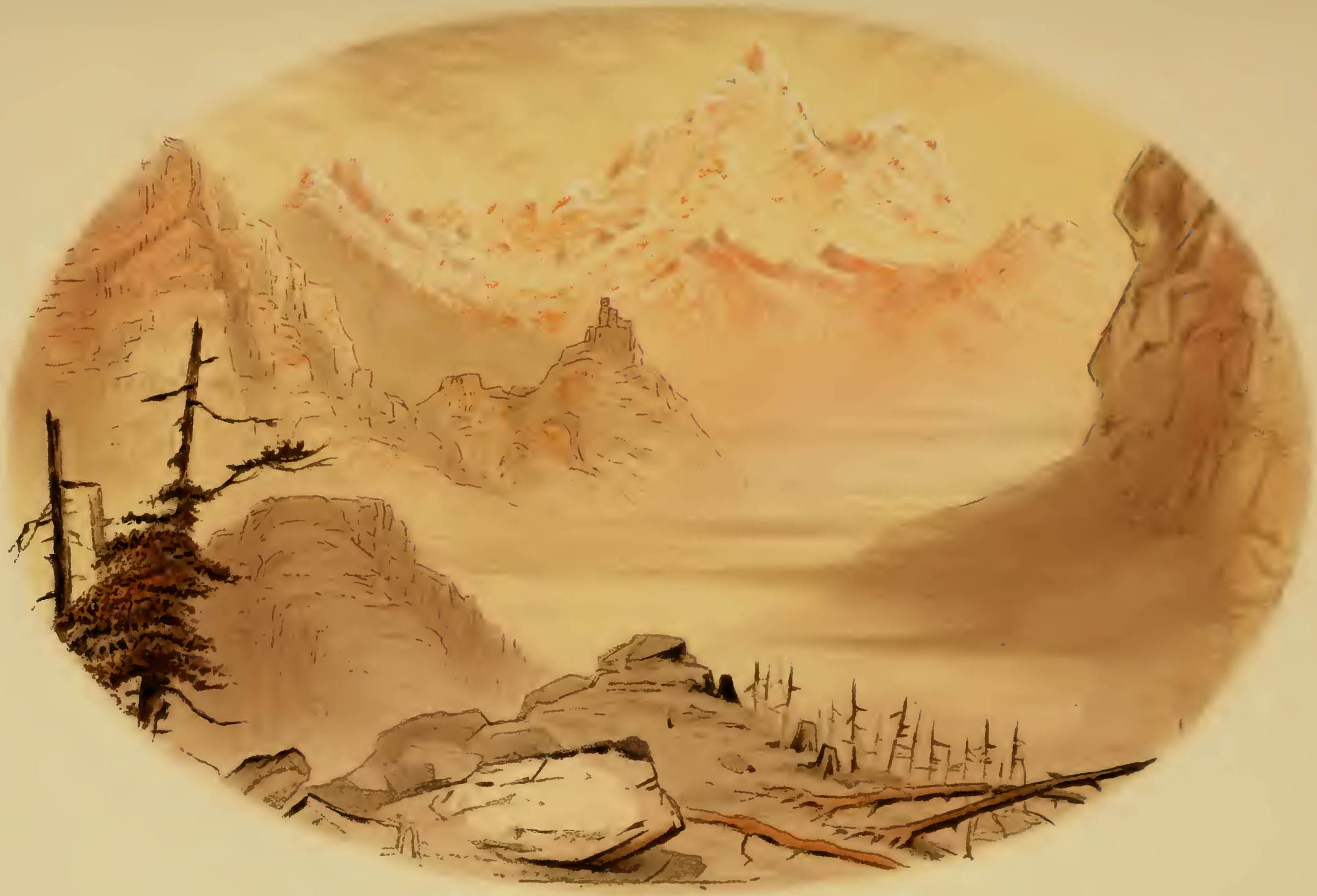

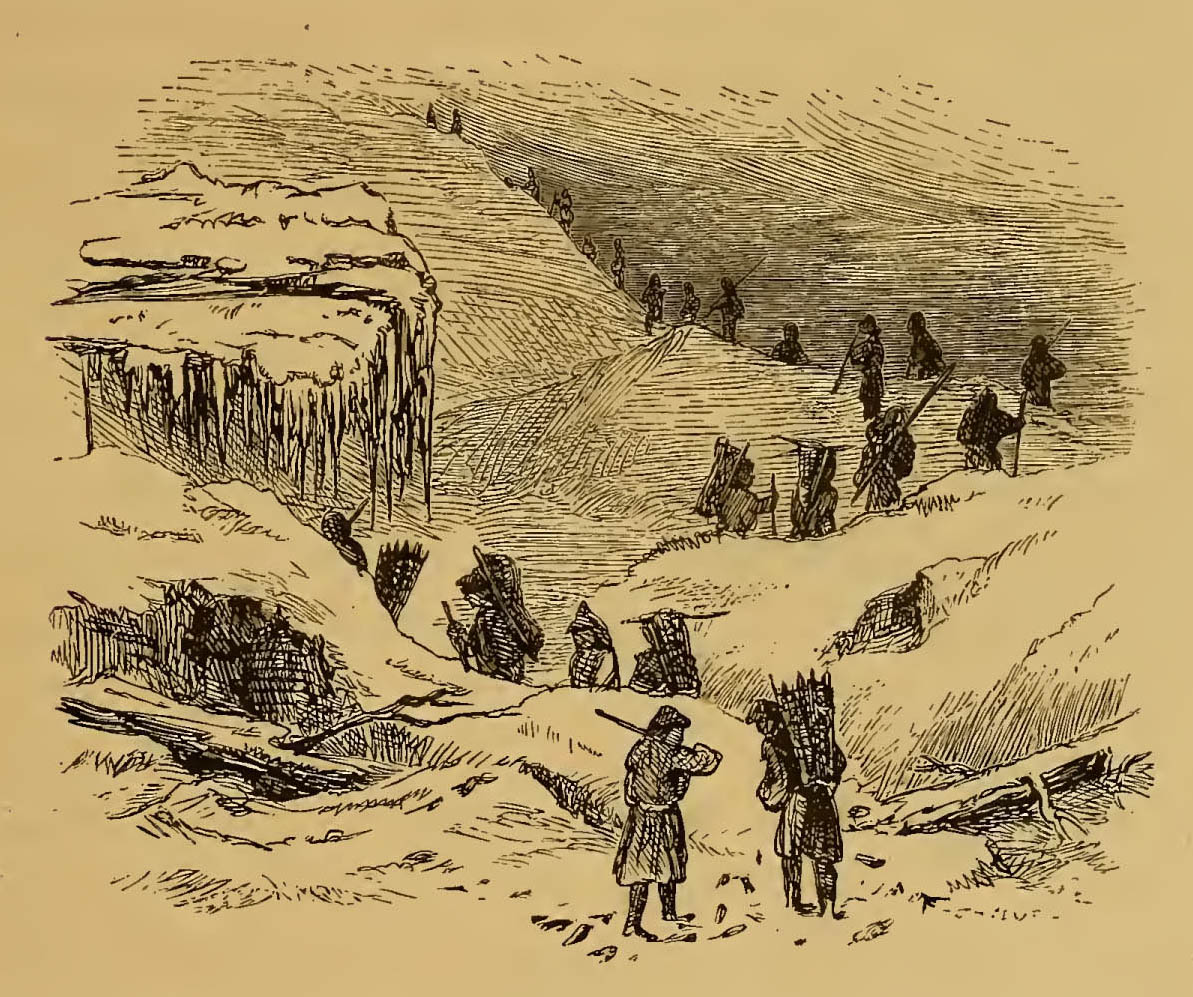

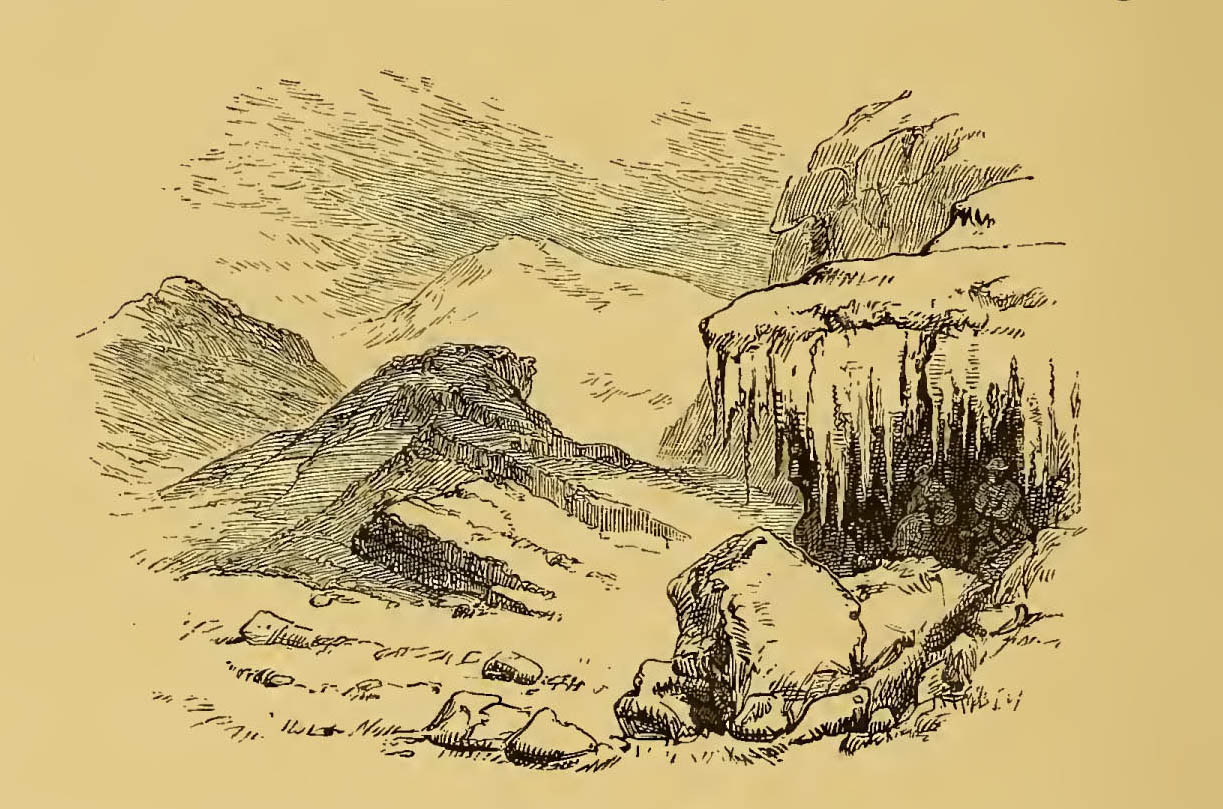

From this place we have our first glimpse of the snowy range, one or two of the loftiest peaks just peeping over intervening mountains, as if to show us something of the glory that lies beyond, and the view looking across the broad Mahanuddee — a shallow river, but clear as crystal — is very imposing with the dark belt of jungle at its base. We do not linger here, however, for the Terai is the abode of leopards, tigers, the wild elephant, rhinoceros, boa-constrictors, and other objectionable reptiles and fauna; and for every reason is it unsafe to pass through it — a distance of eight or nine miles — after sunset.

The road, broad and level, is enclosed by dense cover on either side. To the right, to the left, before and behind us, nothing is seen but dense and impenetrable jungle. And this is by no means an agreeable part of our journey; for although the creatures I have mentioned are not given to display themselves to the nervous traveller between the hours of sunrise and sunset, yet the mere knowledge of their existence kept us perpetually on the alert, each movement of a branch suggesting a tiger, every rustle in the tall dry grass, a serpent.

Terrible tales are related of the manner in which natives have been attacked when passing through it at night, which they sometimes do in companies. And there was nothing to prevent their attacking us, had they been so minded, in broad daylight: but there would have been no one to describe the tragic scene, for not a wayfarer did we meet the whole distance. We passed, however, a skeleton of more than one cow, telling its own tale of midnight orgie.

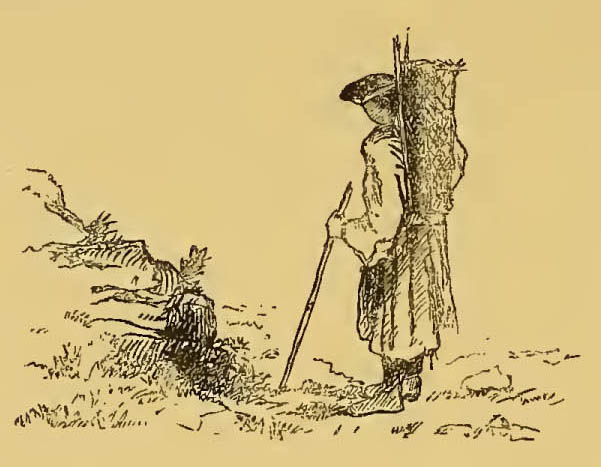

Having reached Gareedura, a small village on the other side of the Terai, we found, to our disappointment, that the ponies we expected to be waiting to take us on to Punkahbaree, although ordered several days ago, had not been sent. Unwilling to delay our journey, F— decided on walking, and after much difficulty succeeded in obtaining from one of the villagers an uncovered hackery for myself and the baggage. In the next page will be seen the interesting picture I make, jolting along the road, restrained in my longings to wrest from the driver's hand the goad with which he keeps poking first this poor beast, and then that, and retaliating upon him with good measure for his cruelty, only by the consoling reflection that probably they had likewise been bullock-drivers in some previous existence, and that their turn had come at last.

Although the ascent to Punkahbaree is gradual, the character of the flora changes at almost each step. We have already lost sight of palms — those melancholy trees so distinctive of the plains — and passing by a large tea plantation, we make our triumphal entry into the little station, where there is an exceedingly nice staging bungalow, in which we put up for the night, starting the next morning for Kursiong, our last resting-place before reaching Darjeeling.

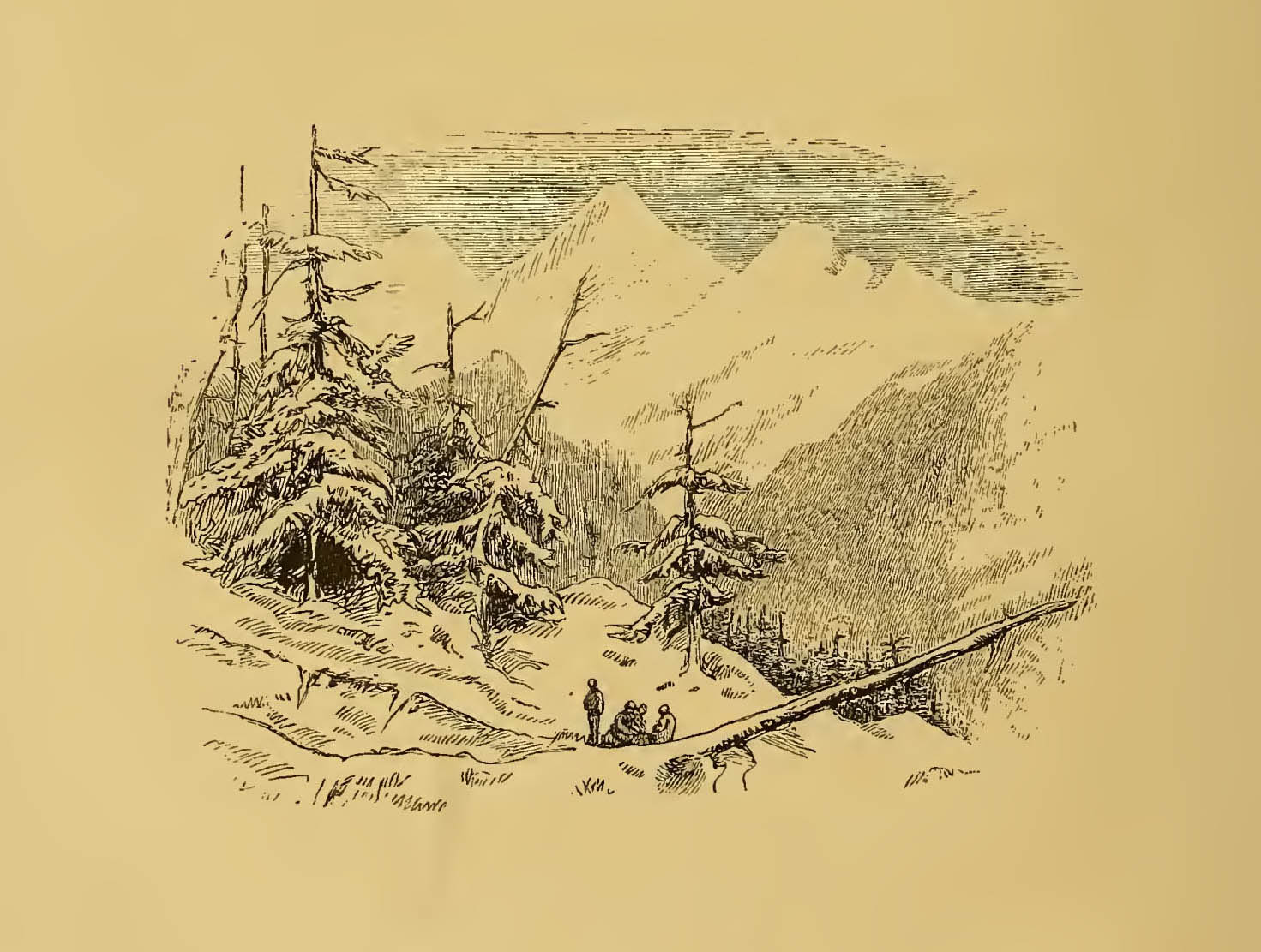

We have now exchanged the vegetation of the tropics for noble forest trees, which clothe the mountains that surround us in confused masses on all sides, and which constitute what are called the Outer, or Sub-Himalaya. Looking back whence we came, we see stretched below us a vast and almost limitless Steppe, the plains of Bengal; and the eye wanders over billows of blue mountain, each lessening in height as it nears them, till the last is seen to merge into the vast ocean-like expanse, that ceases only at the horizon.

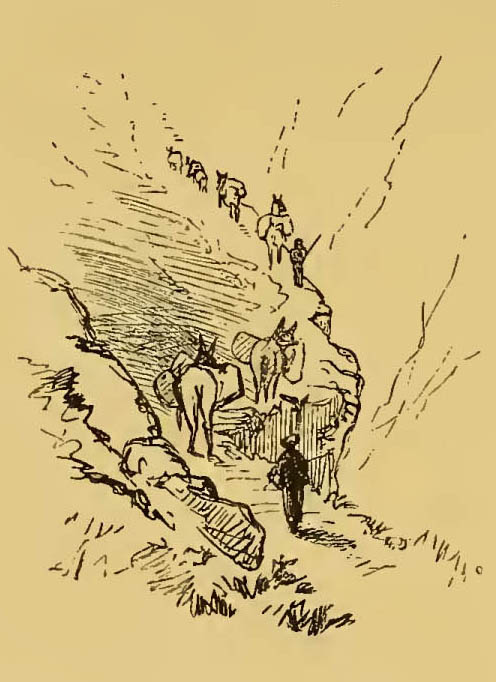

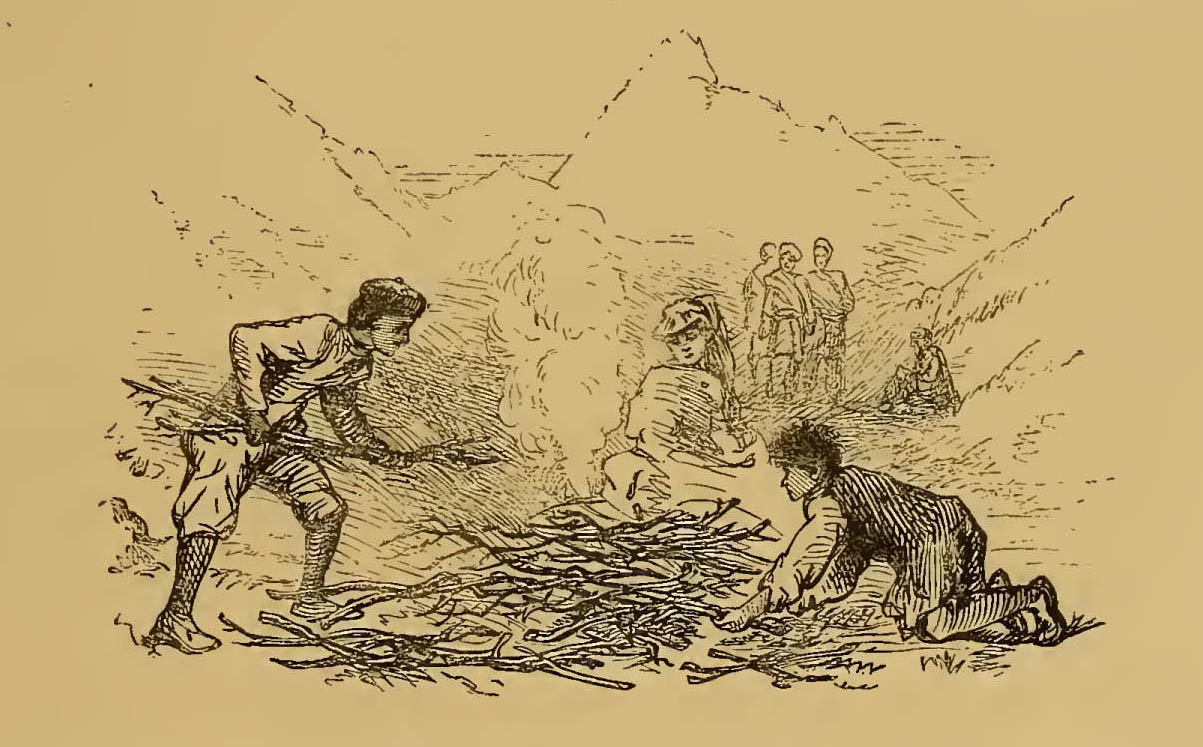

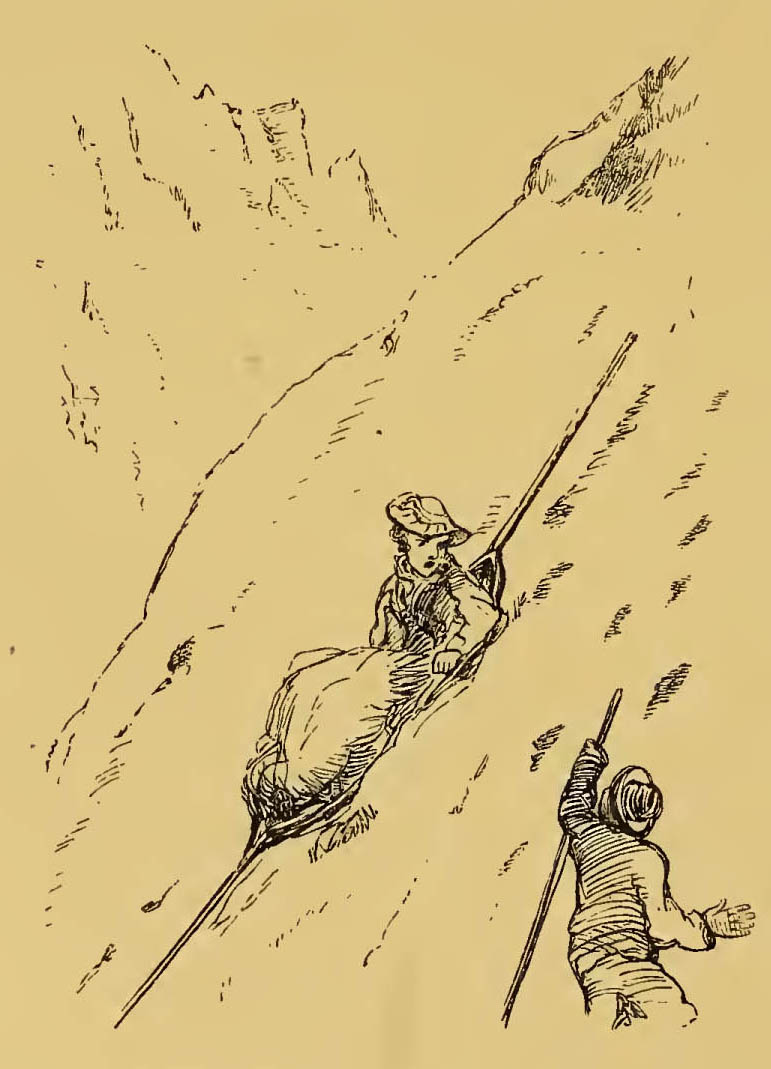

The syces (grooms) in charge of our ponies having arrived during the small hours, we leave Punkahbaree the following morning, whilst the dew still lingers on the sward, and begin zigzagging up the steep path, between banks covered with ferns and lycopodia, shaded by gigantic trees draped with a soft net- work of leguminosæ, in flower, which in many instances cover their trunks completely, and hang from each branch in long filaments like ships' cables. Orchids cling to the moist bark with slender thread, their succulent leaves and wax-like blossoms contrasting sweetly with the vivid green of the moss, which often forms their bed. White and purple thunbergia cover many of the less lofty trees, the wild banana, and the spider-shaped leaves — eight feet broad in many instances — of the pandanus palm, whose glorious plumed head waves gently to and fro in the morning breeze; and having ascended two thousand feet since leaving Punkahbaree, we meet with oaks, birch, and other trees, which recall to memory one's native land, and the change of climate as we proceed becomes very perceptible.

A ride of six miles brings us to Kursiong, our first introduction to which is a dismal and dilapidated little graveyard, situated close to the roadside, with no fence whatever surrounding it, the dusty, forsaken-looking mounds being hardly recognisable amongst rank weeds and grass.1 There is always something very sad, in approaching the haunts of men, to have the truth forced upon one's mind, that wherever the living congregate, there must also be a place set apart for the dead; and although a common truth enough, it is yet one to which somehow we never grow quite accustomed. But this neglected little place impressed me with unusual sadness, containing as it does the graves of those who have died in exile in this strange though beauteous land, on which no loving eye has probably ever gazed, or tender hand has strewn a flower.

A gentleman at Kursiong, not personally known to us, but merely a friend's friend, having heard of our coming, sent a messenger to Punkahbaree to await our arrival with a letter, containing, with true Indian hospitality, an invitation to spend a few days at his house en route; an invitation it would have been almost ungracious to refuse, even had not inclination prompted our availing ourselves of it, which it did in this instance, for we were both truly rejoiced at the prospect of a little rest. The house is a charming one, and, unlike those we have hitherto seen in the hills, built very much in the English style. It stands on the extreme summit of a conical mountain, backed by mountains higher than itself, covered with rhododendron and magnolia-trees, and commanding deep blue valleys on either side; but although we are now at a considerable elevation, we are as yet scarcely on the threshold of the wondrous Himalaya, and see little more of the snowy peaks than we did at Siligoree. Nor have we quite lost sight of the plains, basking in the sunshine 6000 feet below. How parched and arid they look, even from this distance! and how thankful we feel to have left them behind, as we breathe health and vigour with each inspiration. How our lungs expand and our nostrils dilate, whilst breathing these exhilarating and life-giving breezes! which enable us to realise the more fully all we suffer in the lowlands of Bengal.

Here we are initiated not only into the new delights of a blazing wood fire, but also into the far-famed hospitality of a planter's household, than which nothing can be more perfect and well-bred; perfect, not only because it is real and hearty, but because no gêne is imposed upon the guest, who is regarded in every respect as one of the family circle, there being no such thing as restraint or 'doing company' on either side. Accordingly, on arrival we were at once shown into the suite of rooms appropriated to our use, a native servant soon following with a message from his master, enquiring whether, as we were doubtless fatigued by our long ride, we would not prefer taking breakfast alone in our own apartment.

In the afternoon our host proposed a canter to a tea plantation some miles distant, a proposition to which we very readily responded; and leaving the house at four o'clock, we were soon traversing a bridle path through the very heart of a primeval forest, our Bhootia ponies, accustomed to the roughness of the path, alternately trotting and cantering, their speed alone hindered by fallen trees, which occasionally lay across it; whilst we ourselves were often obliged to bend to our saddle-bows to avoid being decapitated by low-hanging branches, or entangled by the air-roots, that festoon the trees in long garlands, sometimes reaching to the ground.

After an hour's quick ride, we come suddenly upon the estate; and here the glorious forest trees have been cut down to make way for the cultivation of the tea bush, the mountain slopes laid black and bare in all directions.

A tea plantation is eminently unpicturesque, and only interesting, I should imagine, to the eye of a planter. From a distance it presents the unromantic appearance of an exaggerated cabbage garden — acres and acres of stunted green bushes, planted in rows, with nothing to relieve the monotony of form or colour. The leaf is highly glazed, and not altogether unlike the laurel in shape, though much smaller; whilst the flower, which has a sweet perfume, is precisely like that of the large kind of myrtle, at least to a non-botanical observer. In passing through the estate we saw it in all stages of its growth, from the fragile seedling, struggling into existence through the hard dry soil, to the full-grown shrub.

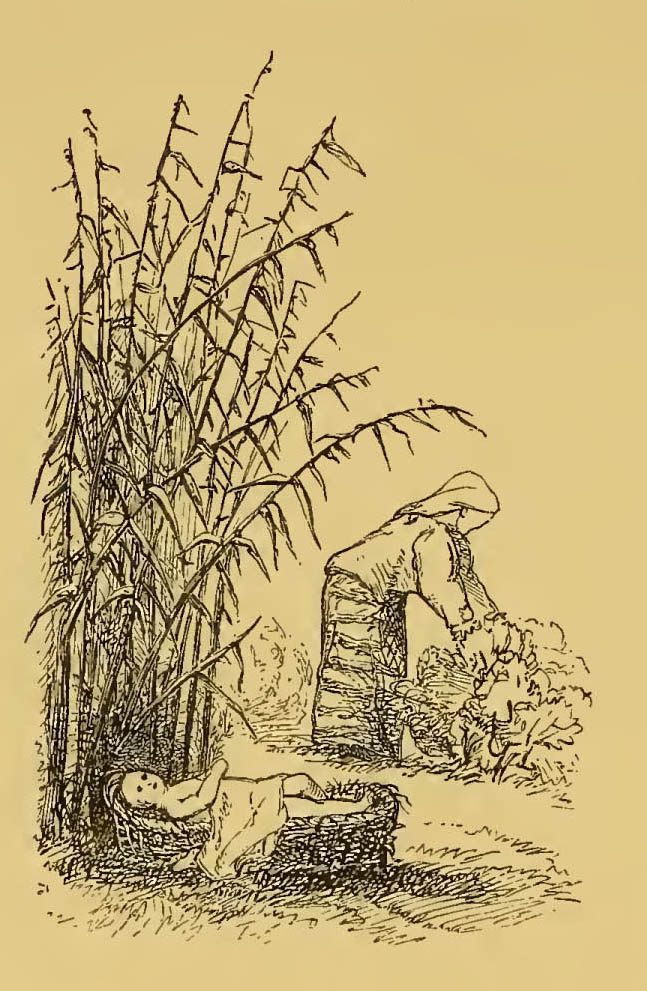

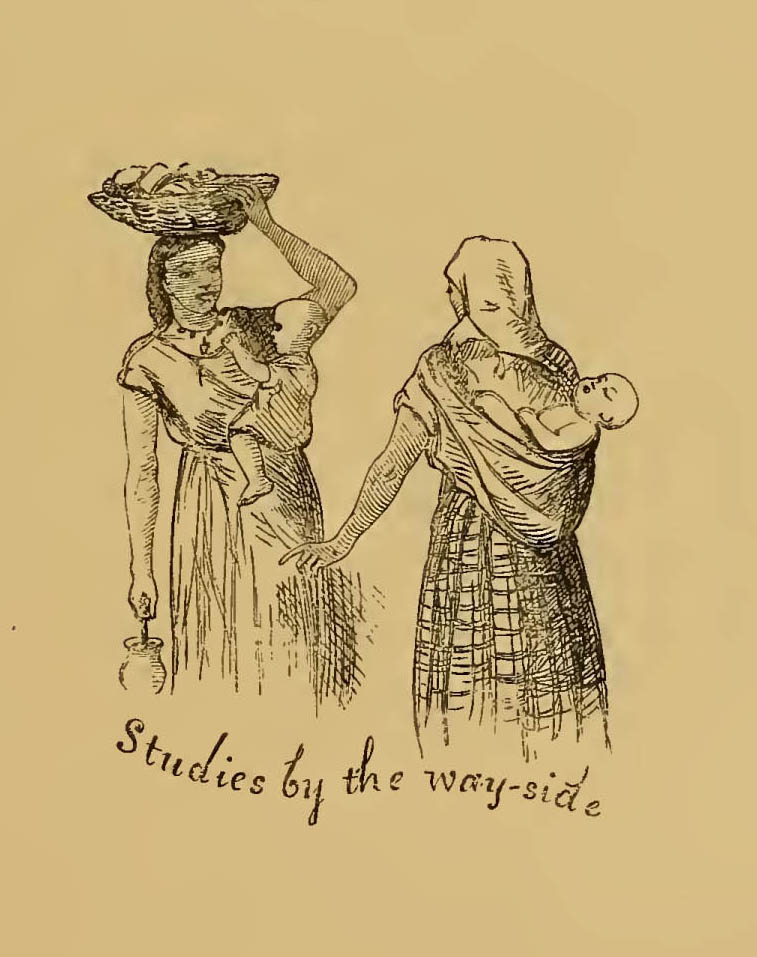

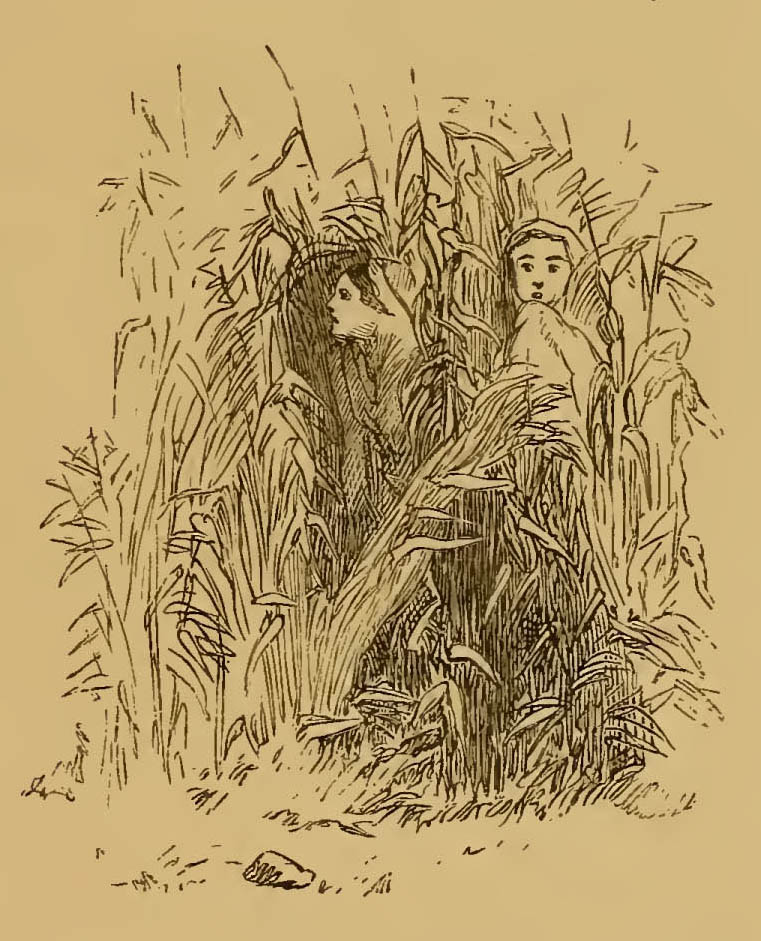

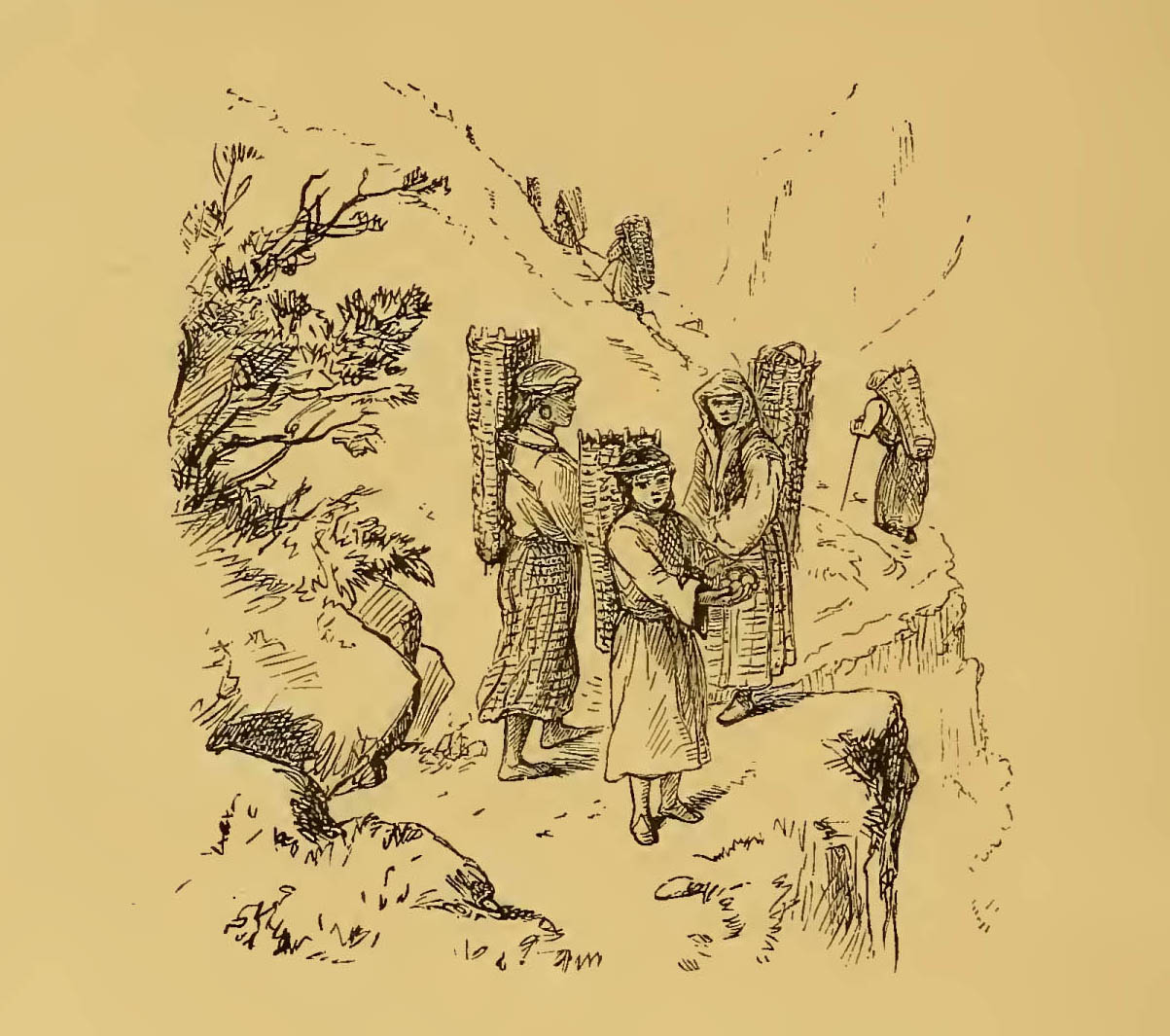

Women and children — who appear to us wonderfully fair after the natives of the plains — are employed in plucking the leaf, which they throw into long upright baskets, the men being reserved for the more laborious operations of hoeing, planting, etc. We pass groups of patient women thus busily occupied, whilst wee babies, from ten days old and upwards, in shallow baskets made to fit them, lie speckled about the ground; placed by maternal solicitude beneath the scanty shadow of the tea bushes, each looking like a little Moses, minus the bulrushes, by the bye. Miriams, however, are not wanting, nor Pharaoh's daughters either, to complete the resemblance.

The costume of these women is very Hebraic in style, often reminding one of the paintings of Scripture subjects by the old masters. Not unfrequently they shield the head with a white or red cloth, folded square, the end hanging down the back after the manner of the Neapolitan women, or else turban-like wound round the head. Their dress is composed of the brightest colours, the three primaries often being seen in combination; somewhat questionable now, however, by reason of untoward vicissitude of wear and tear, but all the better for artistic purposes, yielding a gradation of mellow 'half-tints,'over which Carl Haag would go perfectly mad with delight.

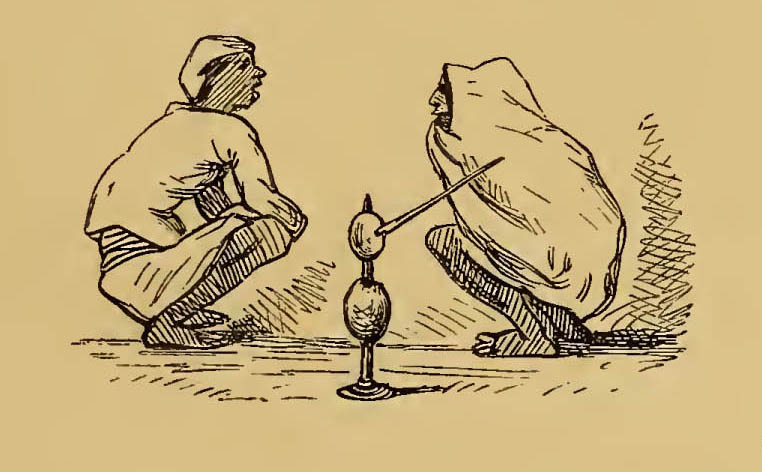

In the middle of the plantation we come to a long low range of buildings, where the green leaves are rolled, dried, sorted, and finally packed in square chests ready to be sent to Calcutta for exportation. When the leaves are first plucked, they are thrown into large trays made of thin strips of bamboo, and placed some hours to fade in the sun, after which they are more completely withered by being warmed over a charcoal fire; and are then spread out upon tables, beaten, squeezed, and crushed by the palms of the hands, till the leaves are rendered thoroughly moist by the exuding of the sap, when they are again placed in the sun, before being subjected to the first roasting process. For this purpose they are thrown into large pans, and tossed about till sufficiently dried; when they are once more rolled by the hands, again roasted in shallow trays, till perfectly crisp and dry, and the tea is considered ready for the market.

In the manufacture of the 'cup that cheers' there certainly is no lack of manual labour, and I think, as a tea-lover, I half regretted having witnessed the process, for it is one of those many cases in which ignorance is bliss.

Then on again by group after group of tea-gatherers, the children looking still more like little Moses, now that we have descended to the region of the waving pampas grass, and they are laid beneath its shade.

Having ridden over fifty acres of plantation, we have now reached its limits, and find ourselves surrounded by wild raspberry bushes laden with ripe fruit, the flavour of which is much fuller and richer than that of our English raspberry, and, being slightly acid, is not a little refreshing after the heat of the tea-house, which was almost unbearable. But how our faces and hands were scratched, and my riding habit torn by encounter with its treacherous brambles!

To vary our ride we re-ascended the mountain by quite another way, entering the forest in an easterly direction. Shadows were lengthening by this time, but the birds were singing still; amongst them the thrush, and above all others — the blessed little thing! — here for the first time in India we heard the cuckoo; upon which F— and I simultaneously reined in our ponies to listen to it. What a surprise it was, that home note in the solitude of this great Indian forest! whilst the plaintive vespers of the little creature, making me feel how many thousand miles we were away from our loved ones in England, caused the very inmost chord of my heart to vibrate, and brought a choking sensation in my throat, which I found hard to get rid of with undimmed eyes. What glorious orchids, too, we saw that day, and what exquisite pendulous lycopodia! and how many sweet-scented wax-like flowers of the magnolia we gathered and stuck into our ponies bridles to carry home!

At the time of which I write, there was no church at Kursiong, and the spiritual interests of the planters and residents generally, of the little station, were left almost uncared for; the military chaplain of Darjeeling occasionally holding Divine Service there, on his way to Jelpigoree — a place he is obliged, amongst his other duties, to visit every few months.

The following day, however, being one of the exceptional Sundays, morning service was to be held in a 'rest house,' as it is called — simply an empty building with four walls roughly roofed in, and used for the soldiers to sleep in on the march to or from Darjeeling — whilst a resident having magnanimously offered to lend a harmonium for the occasion, I was asked to improvise and conduct the choir.

I had had considerable experience of the manner in which musical instruments get out of order in India, not only by the ordinary effects of climate, but also by the ravages of white ants, which not unfrequently take up their abode within them, blocking up the whole machinery by building little walls of primitive masonry, sometimes in a single night; but the prudent measure of testing the capabilities of this one in particular, before doing so in public, unhappily did not occur to me. Accordingly, when I began the usual voluntary, the clergyman's advent was ushered in first by a screech, then by a howl, followed by a deep groan, after which I gave it up in despair; but the gentleman, whose precious possession it was, rising to the occasion, at once came forward, and, performing some mysteries with the pedals, declared in a decorous whisper, that it would 'go all right now.' On the faith of which encouraging assurance, in due time I began playing a chant for the Venite; but the assurance proved a delusion, for the poor thing was so hopelessly gone in the wind, and was so asthmatical — it was evidently a chronic disorder — and it sent forth every now and then such groans and gasps and piteous sighs, that I once more relinquished it, and took to pitching the chants and hymns in a tremulous soprano. The daughters of our host, however, having good voices, quickly took up the strain, and the congregation, who had not had Divine Service for months, or music at one for a longer period still, and who were apparently easily satisfied, declared the singing was charming, and the whole thing a success!

To our minds, at any rate, accustomed to the exciting as well as deeply impressive Military Service of the plains — the 'Parade Service,' as it is called — there was something wonderfully quaint, unconventional, but interesting withal, in the utter simplicity of this one. The homely little building in the midst of the mountains, the people gathering together from such great distances — in some cases wending their way over ten miles of rough pathway — and their devout demeanour, somehow carried one back to the days of the Covenanters, and possessed an impressiveness all its own.

CHAPTER VI.

DARJEELING AT LAST.

IT was a lovely dewy morn, that on which we started for our destination twenty miles distant, our kind host having sent a relay of ponies the previous day to await our arrival at Sonadah, rather more than half way. The road from Kursiong to Darjeeling is a very broad one, skirting the mountains, and winding round their stupendous flanks, very much like the famous Cornice road made by Napoleon I., connecting Nice with Genoa, only on a much grander scale. What azure depths and dark green sombre forests, stretching up, up to the stainless blue! How nobly the broad road winds, and how exciting it is to canter side by side as we breast the wind, which comes borne over icy regions, now not so far away!

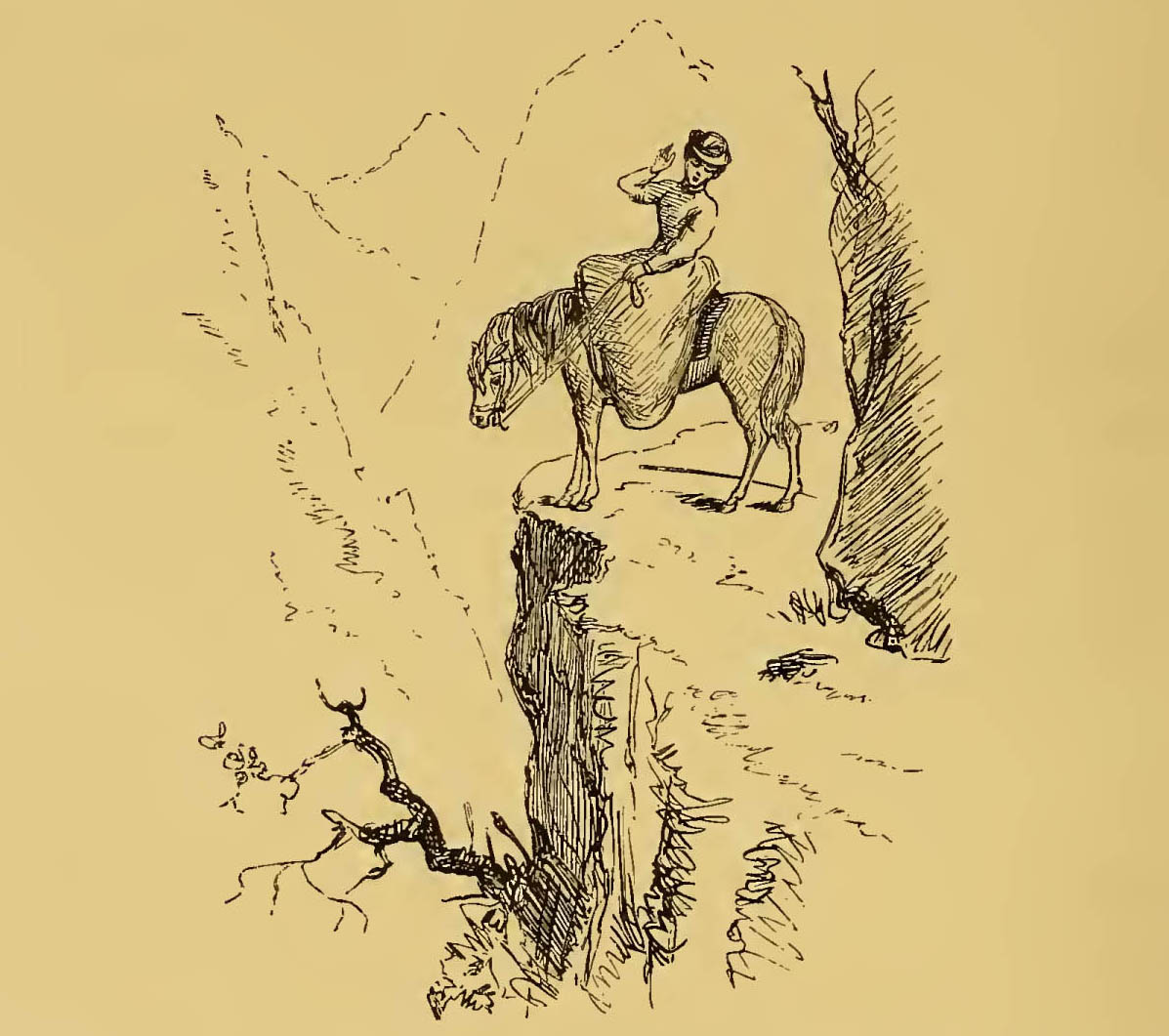

We had not gone more than two or three miles, when we observed, on turning an angle of the road, two men driving a herd of buffalo, large bony animals, stalking leisurely along, their skinny necks outstretched, and square nostrils snuffing the air, as the manner of them is, whether indigenous to mountain or plain. As we rode up, however, instead of their passing us and proceeding on their way, as we naturally expected they would do, for some reason or other they took fright at our formidable appearance, and wheeling straight round, took to their heels and galloped off as hard as they could go; whilst the cries of the herdsmen, and their endeavours to keep pace with them and turn them back, served but as a signal for our ponies to start off too; and away we went giving involuntary chase, soon leaving the men far behind, who kept shouting to us in beseeching accents to stop, and not drive their kine away they knew not whither, their voices growing fainter and fainter each moment, as increasing distance separated us.

From the first, I had lost all control over my fiery little steed, and it was as much as I could well do to keep in my saddle; whilst F— having his own by no means well in hand, it would have been quite impossible to rein them in at this part of the road, which was almost level ground. At length, coming to a little path diverging from the roadway, the buffalo took advantage of it, and fled from their pursuers down the mountain side; with the exception of one big fellow, who, slightly in advance of the rest, overshot the mark and could not turn in time to follow. Infuriated at finding itself deserted by its companions, it dashed on a few paces, and then turned round and faced us boldly, ten yards ahead. Then, as F— brandished his whip and shouted loudly, it dashed off once more, but only to return to the charge again and again; and it was 'On, Stanley, on! charge, Chester, charge!' for more than a mile, when coming to another mountain path, it also happily left us, and was soon lost sight of amongst the thick brushwood below.

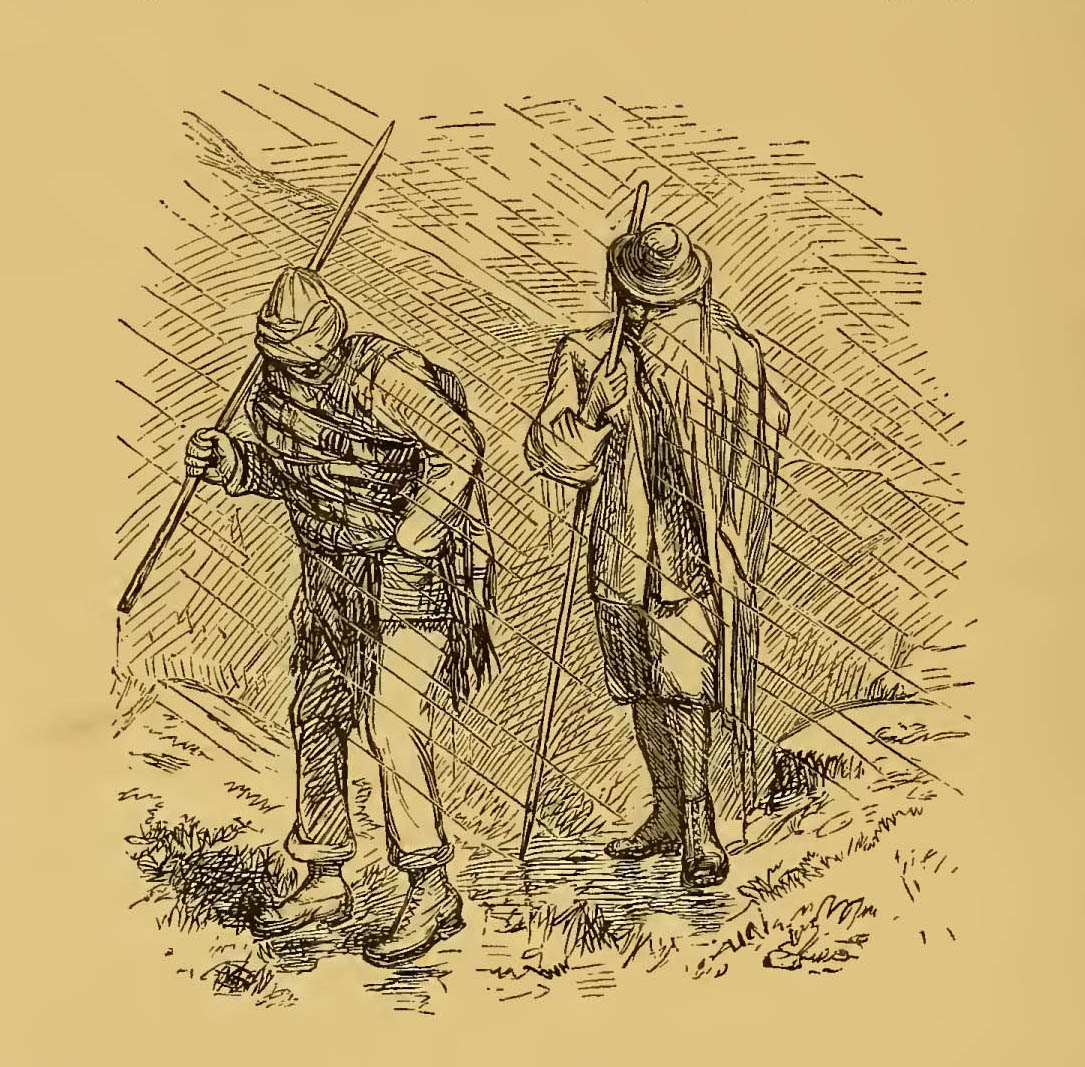

Long before we had time to recover our composure after the little episode just narrated, we were overtaken by one of those dense fogs, of which we had ample experience during our residence in Darjeeling, and which rendered fast riding out of the question. Nor was it easy at all times, even when riding slowly, to steer clear of the hackeries, and the long strings of ponies we met, scarcely more than four feet high, laden with sacks and protruding packs of the gipsy order, all of which had an uncomfortable way of rubbing against us as they passed.

Having, as we imagined, ridden about twelve miles, and accomplished nearly two-thirds of our entire journey, F— accosted the driver of a hackery, and enquired how far it was to Darjeeling.

'Sāt kos (fourteen miles),' was the reply; a kos being equal to two English miles.

Proceeding onwards yet another hour, we saw an old pilgrim plodding along the road, to whom F— repeated the question. After gazing intently at the top of his staff for some moments, upon which he was leaning, as though he expected to find the answer written there, he slowly counted on his fingers, like one making an abstruse calculation, and muttered in Hindustani, 'Well, there was Sonadah, and that was tīn kos (six miles), and then there was "the Saddle," and that was chār kos (eight miles); and then there was Darjeeling, and that was ek kos (two miles), and that made āt kos (sixteen miles) altogether.'

'What!' exclaimed F—, lifting up his voice, 'have we then been going backwards the last hour, misled by the fog? Or are we condemned to journey on perpetually, like the Wandering Jew, never to come any nearer to the goal?'

'Hogā, sahib, hogā,' rejoined the old man, encouragingly, reading an expression of disappointment in our faces, and making use of that provoking idiom, so peculiar to Hindustani, which forms the vague and indirect answer to nine out of every ten questions you may ask a native, embracing as it does the past, present, and future tenses, as well as the conditional and potential.

For instance, if you ask a servant, 'Is So-and-So coming to day?' he will reply, 'Hogā, sahib,' meaning may be. 'Did he come yesterday?' he will still reply, 'Hogā, sahib,' signifying he might have come; and so on. On this occasion, therefore, hogā was intended to convey the consoling assurance, that although Darjeeling was āt kos distant yet, and a long way off, still, if we persevered, it would be, i.e. we should arrive there at last.

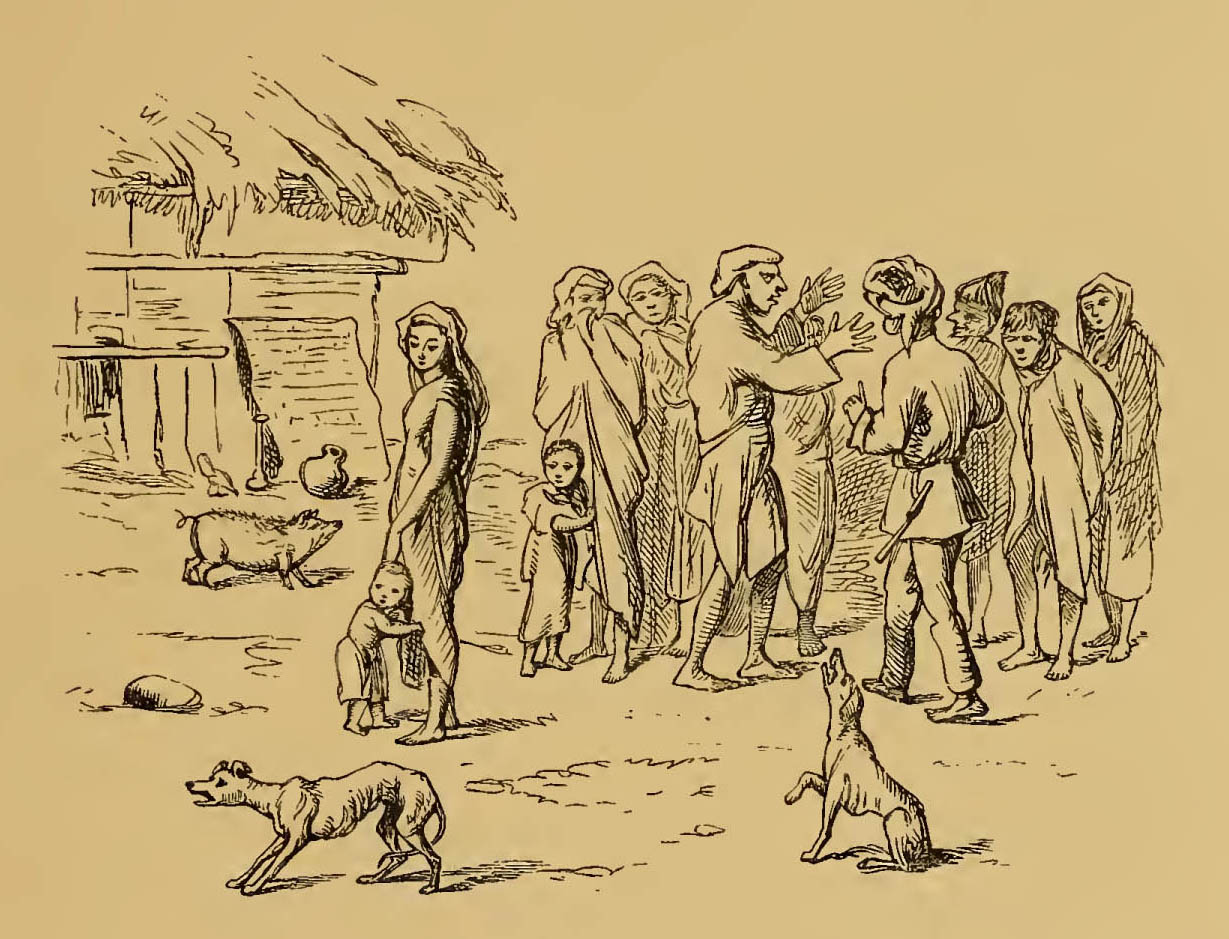

And so we did; at any rate, people told us we were there: a crowd of hackeries to steer through, and fowls and pigs and children to be ridden over, and visions of huts frowning down upon us on either side of the road, all exaggerated in the darkling mist, and a mysterious voice proceeding from the shadowy outline of a native, telling us he was our 'bearer,' who had arrived before us with the luggage, and was waiting to conduct us to the house that had been secured for us.

* * * * * *

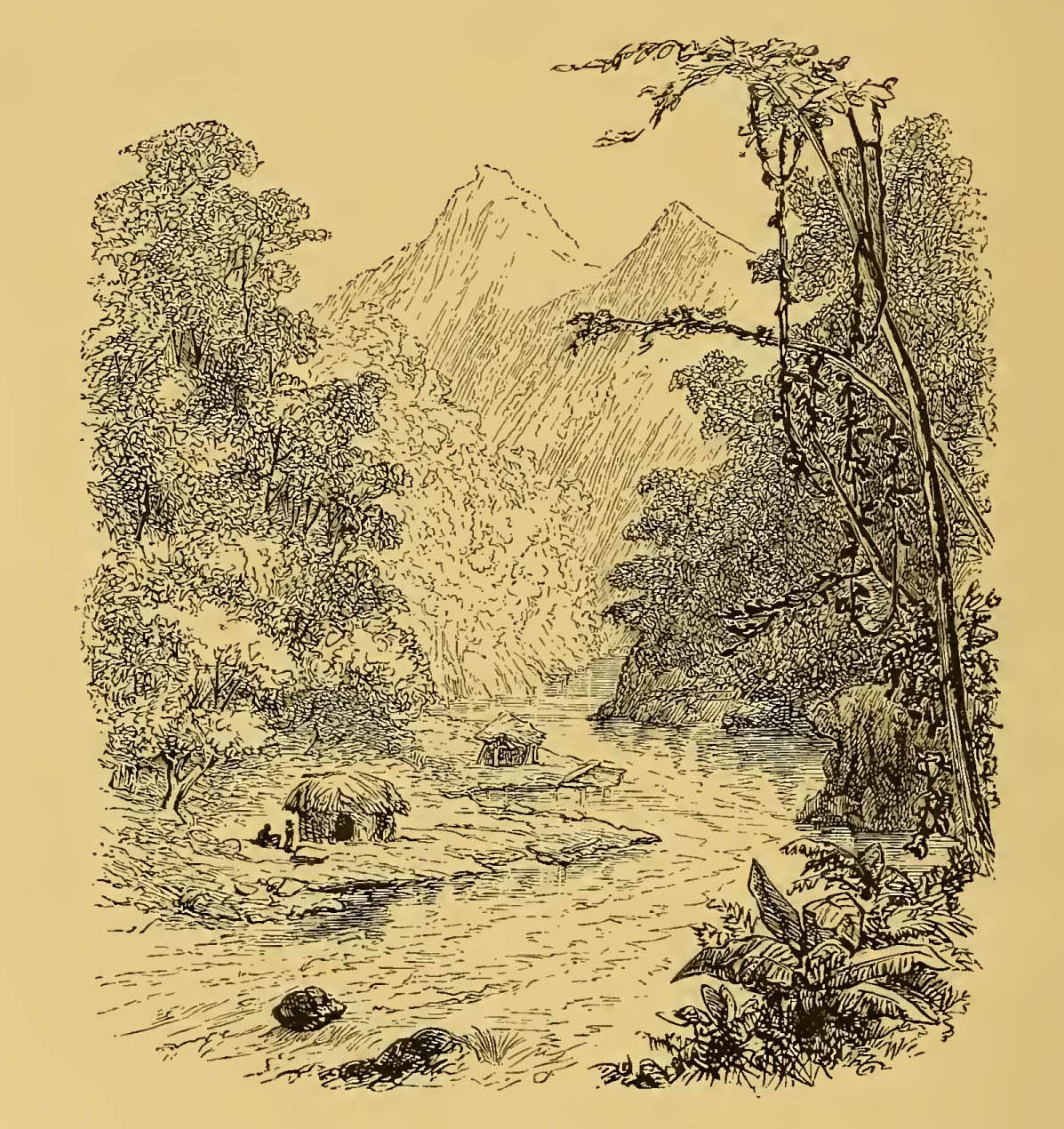

Standing under the porch of our pretty mountain dwelling the morning after our arrival, what a sight presented itself to our view! 'See Darjeeling and die!' has become a familiar aphorism now; and well it may, for how can I ever hope to be able to describe the awful beauty of the snowy range from this spot! Grander than the Andes and the Red Indian's mountains of the setting sun; grander than the Apennines and Alps of Switzerland, because almost twice their height; grander than anything I had ever seen or dreamt of — for what must it be, think you, to fix your gaze upon a mountain more than 28,000 feet high, rising 21,000 feet above the level of the observer, and upon which eleven thousand feet of perpetual snow2 are resting, rearing its mighty crest into the very heavens! Overcome as I am by its grandeur and majesty, I will not attempt a description of it now, for language fails me, but leave it to develope itself as I proceed in my narrative, and the eye once grown familiar to the scene, emotion grows fainter, and forms itself into speech.

CHAPTER VII.

WE PURSUE ART UNDER DIFFICULTIES.

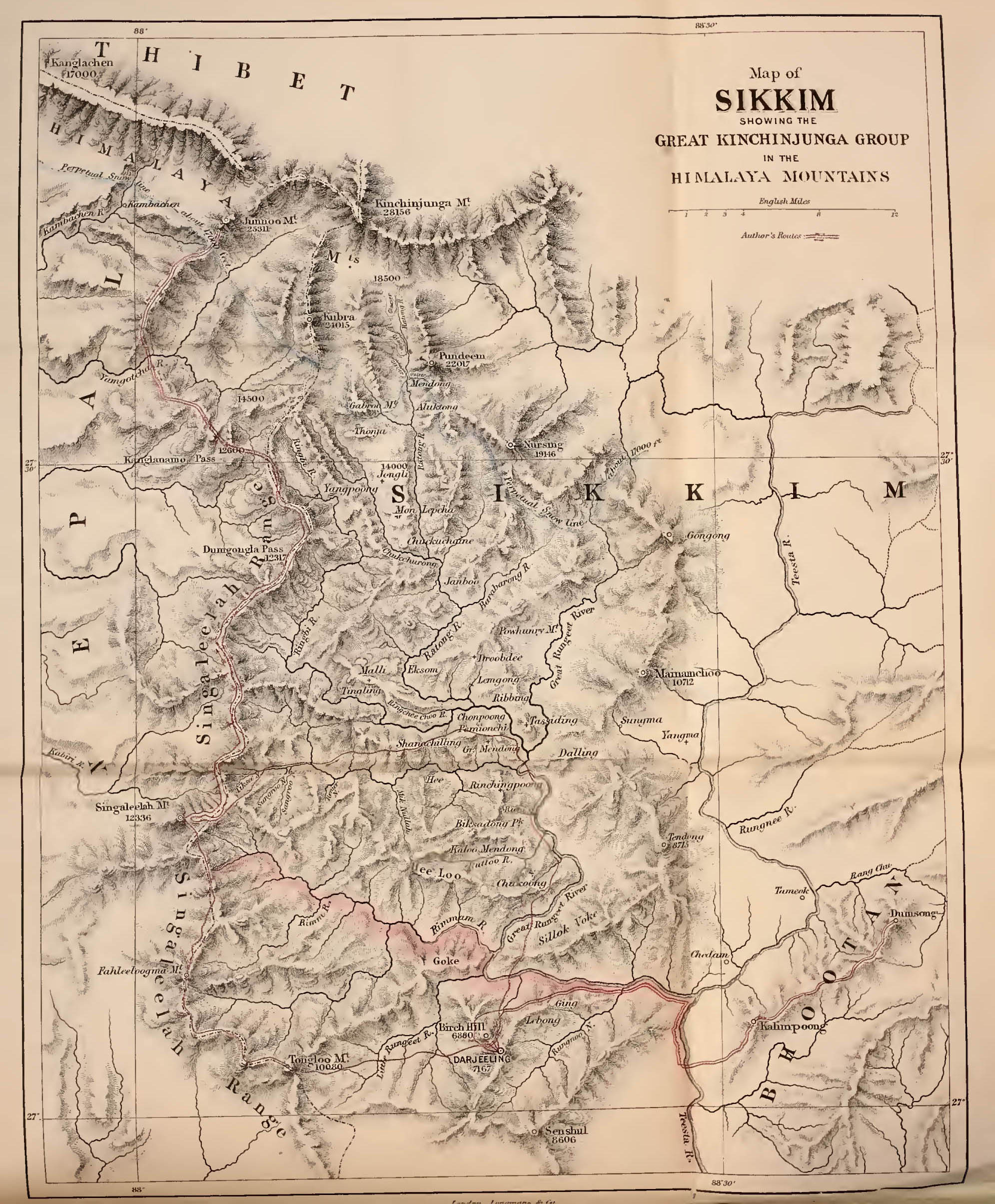

THIS sweet little cantonment, the sanitarium for Bengal, became British territory in 1835, together with a small tract of adjacent hill, ceded by the Rajah of Sikkim to enable our Government to create a convalescent depôt for its troops; in return for which favour it agreed to give 300l. per annum as compensation, the Rajah's 'deed of grant' expressing that he made this cession out of friendship to the British Government; little thinking, in his amiable simplicity, that Darjeeling would ultimately become the key to Sikkim, Nepaul, and Bhootan, or he would doubtless have been less generously disposed.

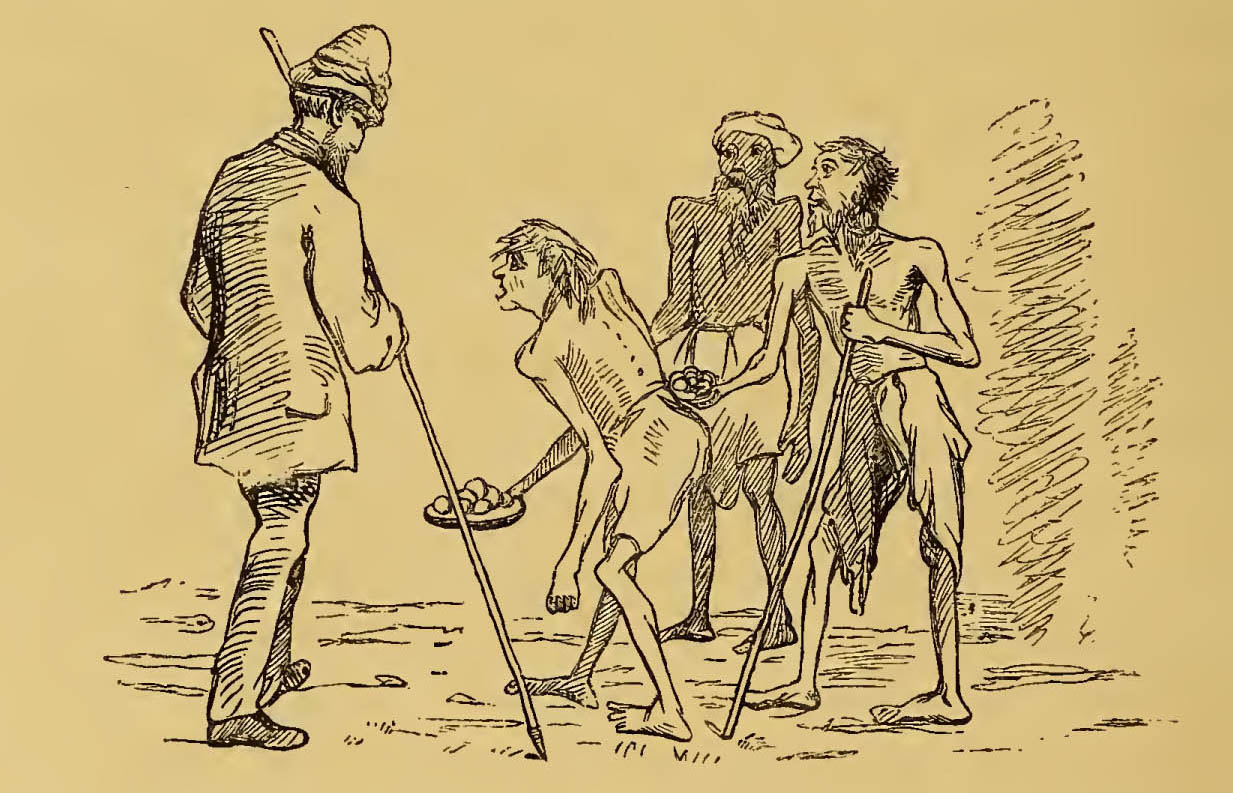

Its native population numbers upwards of 20,000, consisting of various tribes, Bhootias, Lepchas, Limboos, and Goorkhas; the three former having originally migrated from some province in Thibet. They are, for the most part, an inoffensive and peace-loving people, particularly the Lepchas, a nomad race, natives of Sikkim, who possess many virtues and none of the vices of the more highly civilised dwellers of the plains, the Mahomedans and Hindoos.

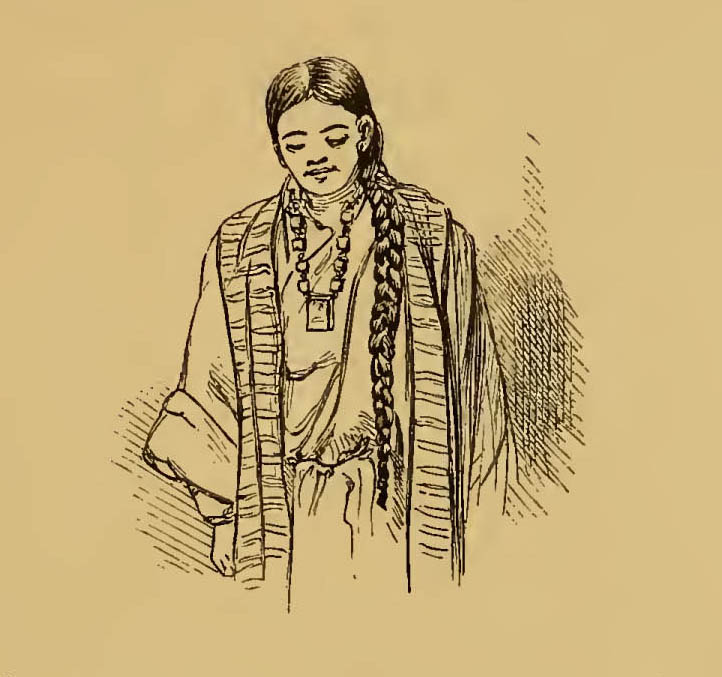

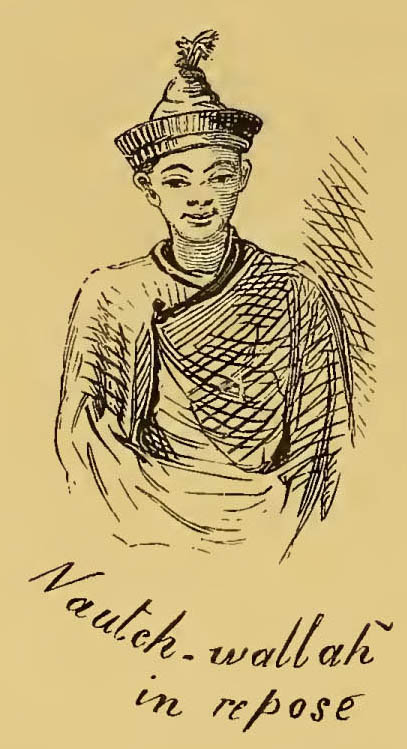

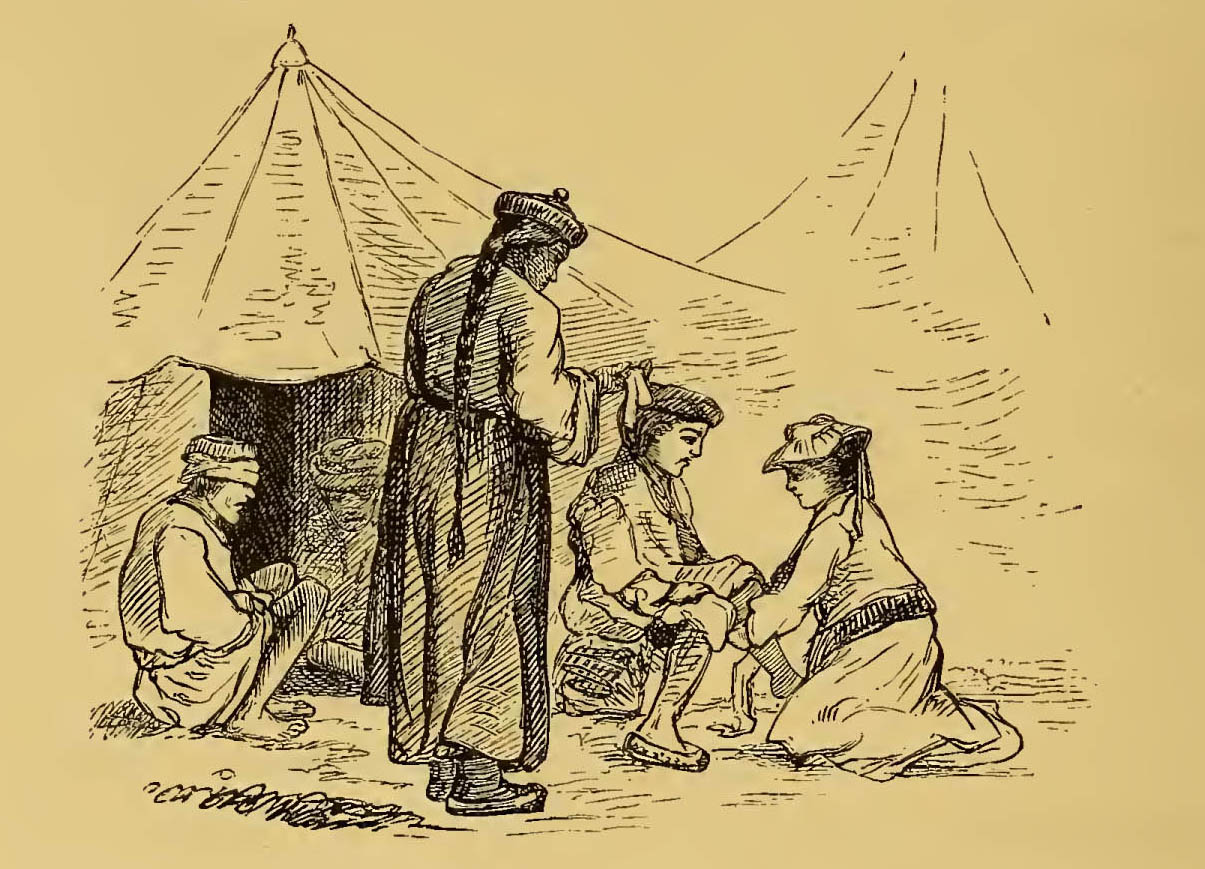

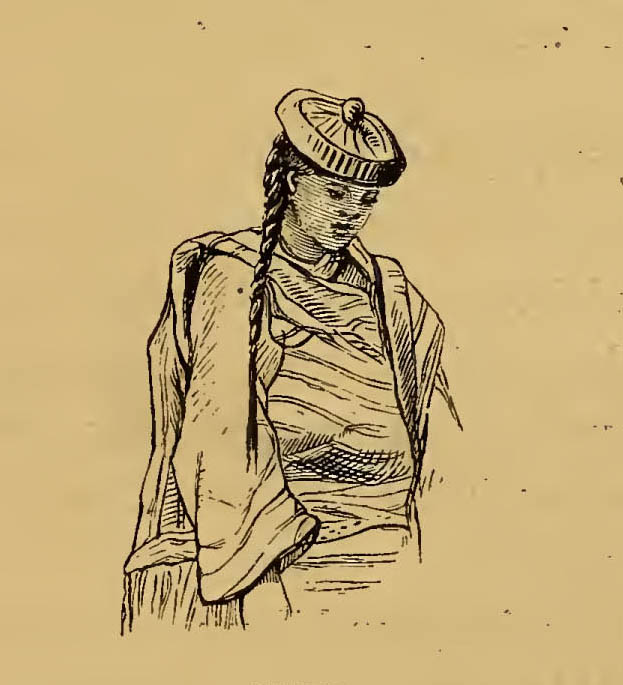

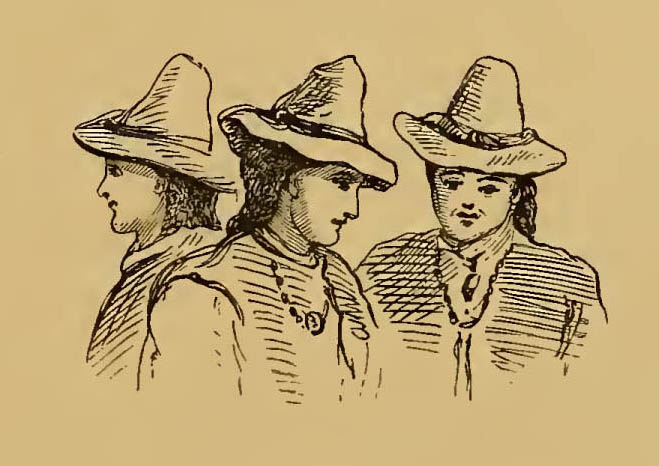

The dress of these mountaineers is exceedingly picturesque, varying with each tribe as greatly as their language. In a climate like that of the Himalayas they are, of course, fully clad, the material being composed of some warm woollen fabric, woven by themselves in small triangular looms, after a very primitive manner. The Bhootias wear a long loose robe of some brilliant colour; brilliant, that is to say, until subdued by the mellowing influences of time, and its concomitant. This is confined at the waist by a long narrow scarf or girdle, the front of the robe above the waist forming a natural pocket, or 'opossum-like pouch,' in which they keep, when travelling, their little worldly all. I have seen one Bhootia produce from his pouch a canine mother and several puppies for sale, and another any number of cats! whilst from their belt hangs a very formidable knife, fully half a yard long, enclosed in a leathern scabbard, often highly chased with silver. A powerful, square-built, and very manly tribe, armed with these knives, they appear not a little hostile, some experience of their harmless habits being necessary, before one can feel altogether at ease in living amongst them. They are, however, on the other hand, a very wily and cunning people, with much of the Chinese nature about them; and when one of old gave utterance to that memorable and not very complimentary statement regarding the truthfulness of mankind, he most assuredly made no exception in their favour.

Very different in each respect are the gentle Lepchas, who are truthful and honest to a singular degree, those who have had transactions with them declaring that seldom if ever have they known them commit a theft or tell a lie. Their complexion is fair and ruddy, but of that yellowish tinge observable in all the Mongolian races, and, like the Chinese, they are oblique-eyed and flat-faced, giving one the idea that they must have been accidentally sat upon when they were babies, and that they have never got the better of it since.

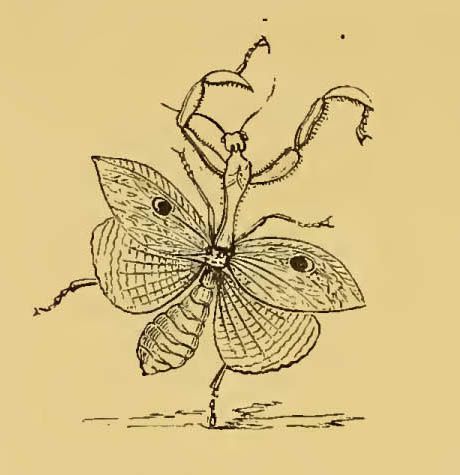

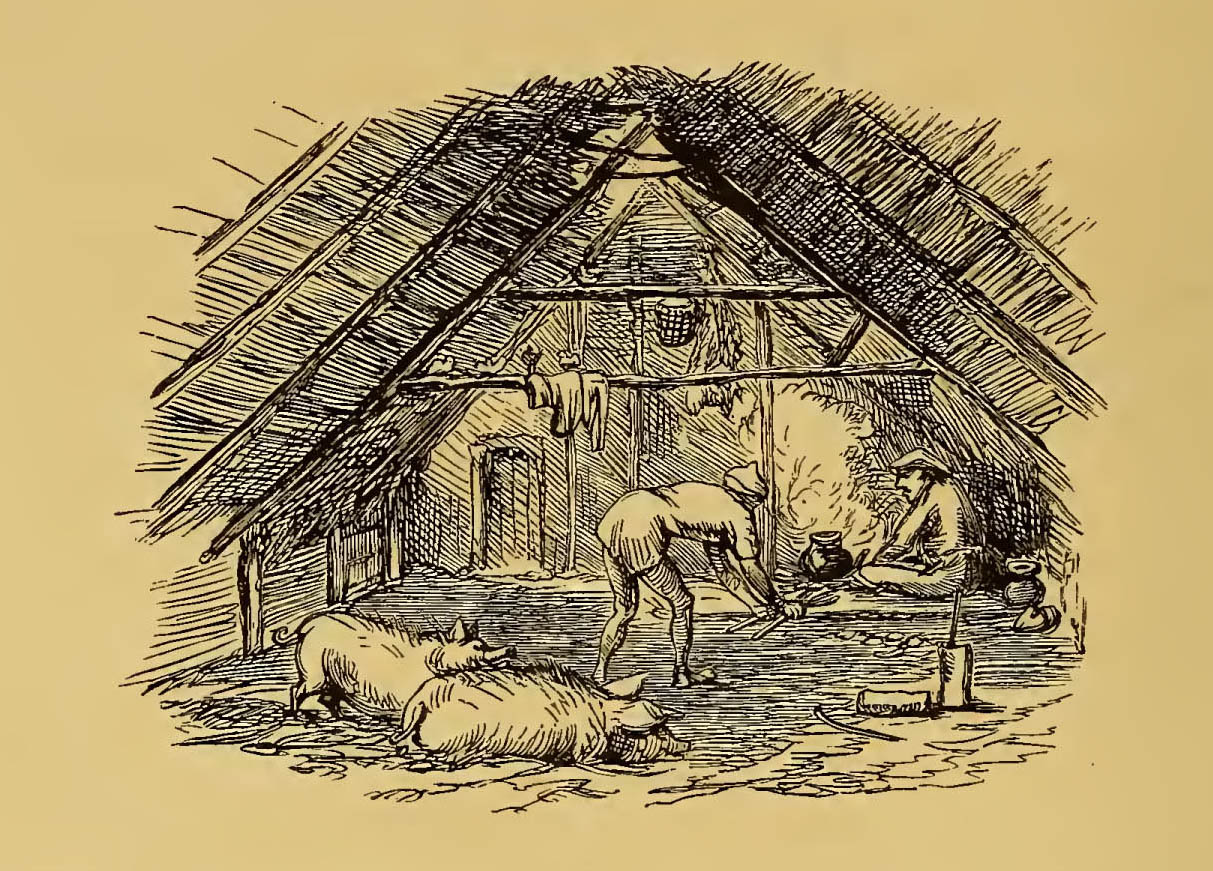

These peculiarities, however, are more common amongst the Lepchas of Darjeeling, for in the 'interior' of Sikkim, as I afterwards found, when we made a tour to the region of perpetual snow, they frequently possess great regularity and even beauty of feature. These people are intelligent, and great entomologists, scarcely an insect or tiny earth-worm existing for which they have not a name: but although they have a written language, they have no recorded history of themselves. They are much smaller of stature than the Bhootias, and effeminate looking, partly from the fact of possessing neither beard nor moustache, which they destroy by persistent plucking. They also part the hair down the middle of the head, plaiting it into a tail reaching below the waist. Rightly have they been designated the 'free, happy, laughing, and playful no-caste Lepcha, the children of the mountains, social and joyous in disposition.' They are, however, an indolent race, taking life easily, and when not basking in the sunshine when there is any, or huddling inside their huts with the pigs when there is none, their favourite occupation is butterfly catching, with which they contrive to earn a tolerable subsistence, almost every visitor to Darjeeling, scientific or otherwise, making a collection of Lepidoptera, for which the neighbourhood is justly celebrated.

The costume of this tribe consists of a long striped scarf or toga, fringed at each end, with which they drape themselves in an exceedingly graceful manner, allowing one end to fall loosely over the shoulder. A bow, a quiver of poisoned arrows, and a butterfly-net complete their equipment, not forgetting the knife, or 'ban,' suspended from a red girdle, a long straight weapon enclosed in a wooden sheath, quite different in shape from those used by other tribes, called 'kookries,' which are short and curved.

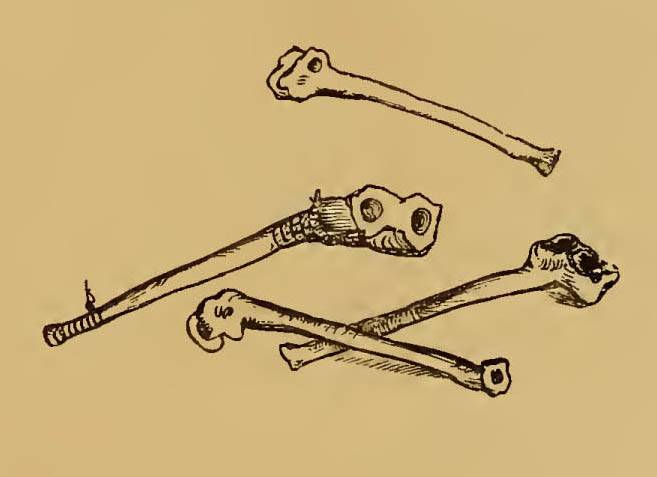

The dress of the women of each race is almost alike; a short petticoat, striped with green, red, blue, and orange, tight bodice, with chemisette and sleeves of white calico, or a long white robe open down the front, and worn over all. Those of the better classes adorn themselves with gold and silver filigree ornaments, in which real agates and turquoises, procured from Thibet, are sometimes set; whilst a tiara of black velvet, ornamented with large coral or turquoise beads, encircles the head. They also wear amulets, or charm-boxes, containing prayers and relics of departed Lamas, such as nail pairings, &c.; and happy and thrice blessed is that fair one supposed to be — her fortune, in fact, made for life — who possesses that most precious of all relics, a departed Lama's tooth.

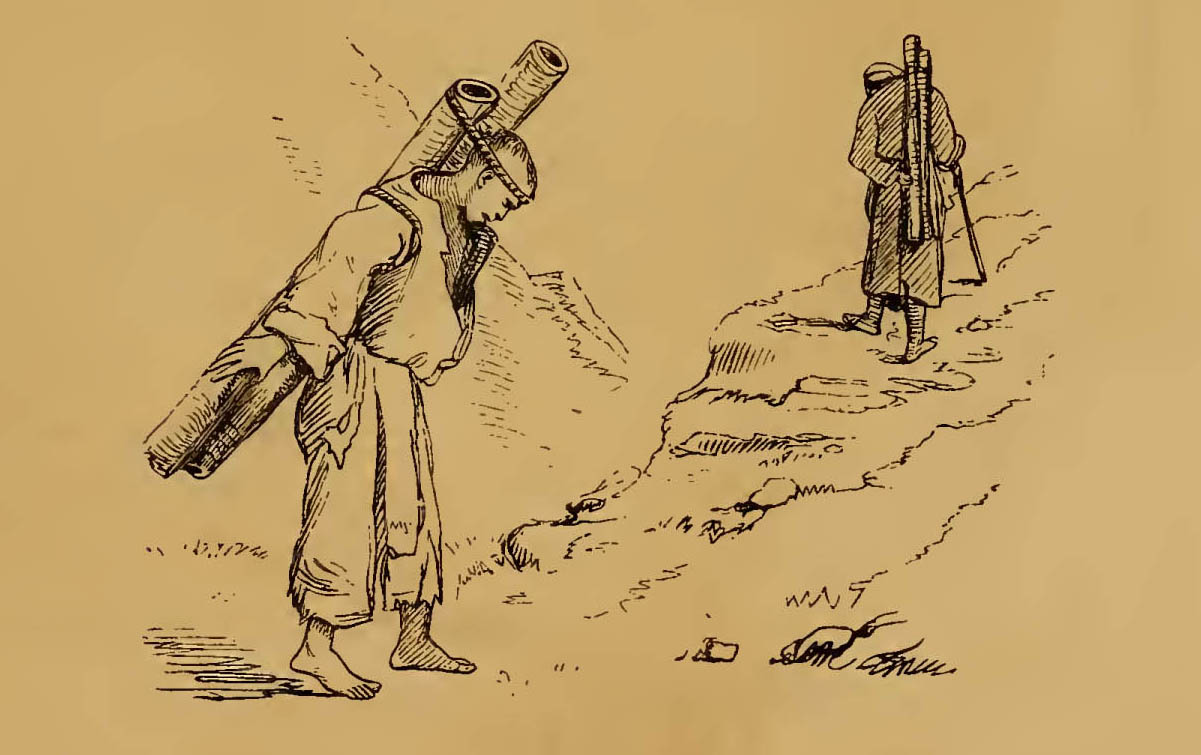

The Lepchas, though an indolent race themselves, do not allow their wives to enjoy the same privilege, but constitute them their domestic drudges, agricultural labourers, and beasts of burden also. They do not marry young, like the natives of the plains; and when they do marry often have to pay heavily for their wives, a Lepcha father frequently making a small fortune out of the sale of his daughters; some few, on the other hand, being sold for the modest sum of one rupee (two shillings). Occasionally the marriage is permitted to take place before the money has been paid; but in that case the husband becomes, like Jacob, the bondsman of his wife's father, and the wife never leaves her father's house, until the stipulated sum has been either worked out or paid in full.

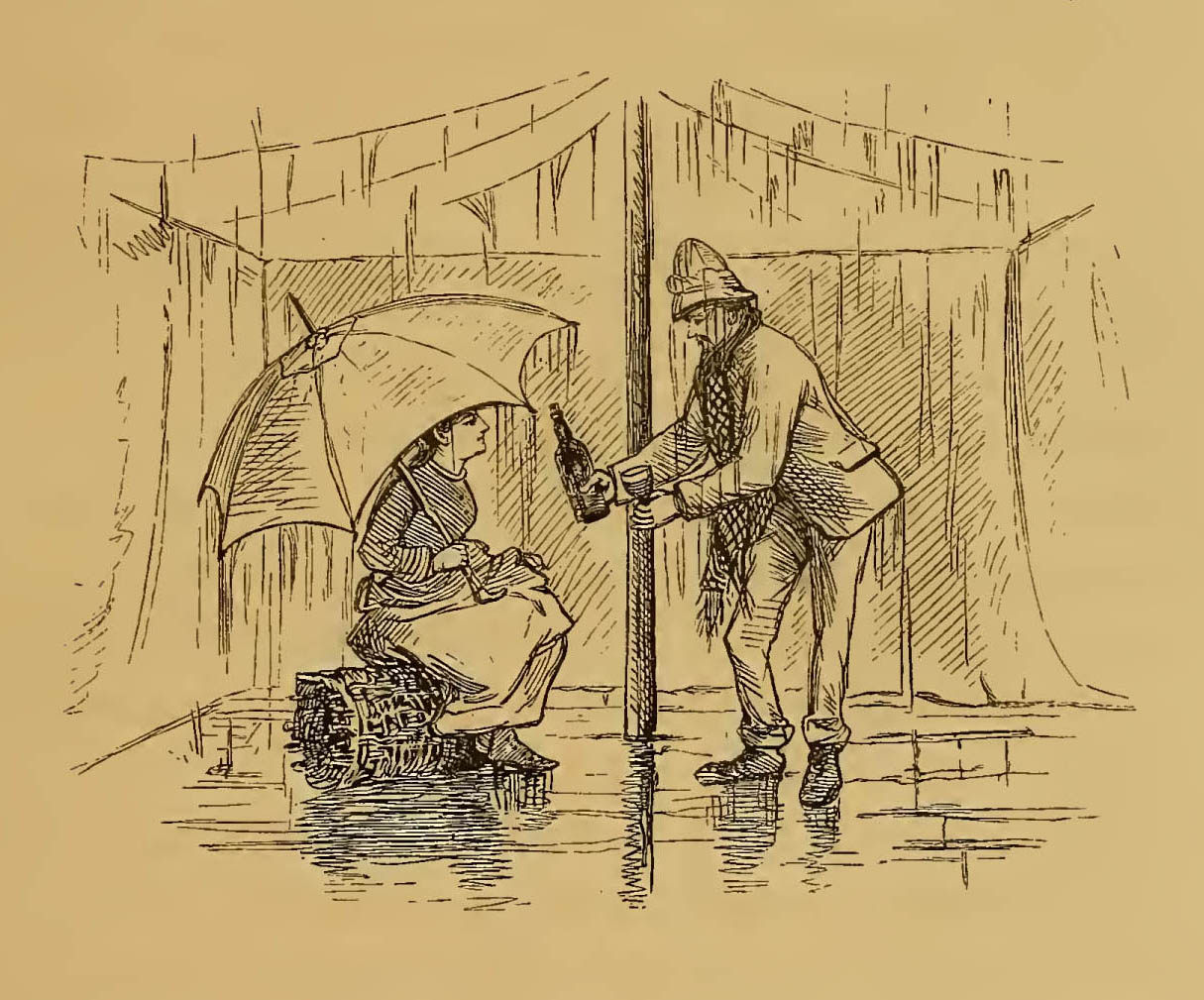

The planters exempt their coolies from work on Sundays, a circumstance the latter take advantage of, by going to the market, or 'bazaar,' as it is called, to make their weekly purchases. This is situated in a large open space, where the vendors of woollen cloths made in Bhootan, silks woven from the fibre of a worm that feeds on the castor-oil plant, grain, vegetables, and other produce, all squatted on the ground, display their wares. It is consequently always at its fullest on Sundays, when the people, clad in every conceivable colour and costume, flock to it in crowds, and, collected together, form a very interesting and picturesque scene. On one side of the bazaar is a Mahomedan mosque, surmounted with its white cupola, where the devout sons of the Prophet, who have migrated hither from the plains, are wont to resort at their hours of prayer. Above this is the convent, and beyond all, bathed in sapphire, stretches a wondrous expanse of mountain, half filling the sky.

It is one of the prettiest sights possible to see the picturesque mountaineers wend their way upwards from the plantations on their way to market, dressed in all their Sunday best, their hair often adorned with flowers. The ears of the Lepchas and Limboos have large holes in them, from the perpetual dragging of heavy silver earrings; and these they not unfrequently fill with flowers, sometimes those of the large pink magnolia, sometimes the scarlet blossoms of the cotton-tree: the women carry their children on their backs in baskets; and there never were people, I really think, in all the world, half so merry, and free, and light-hearted as these.

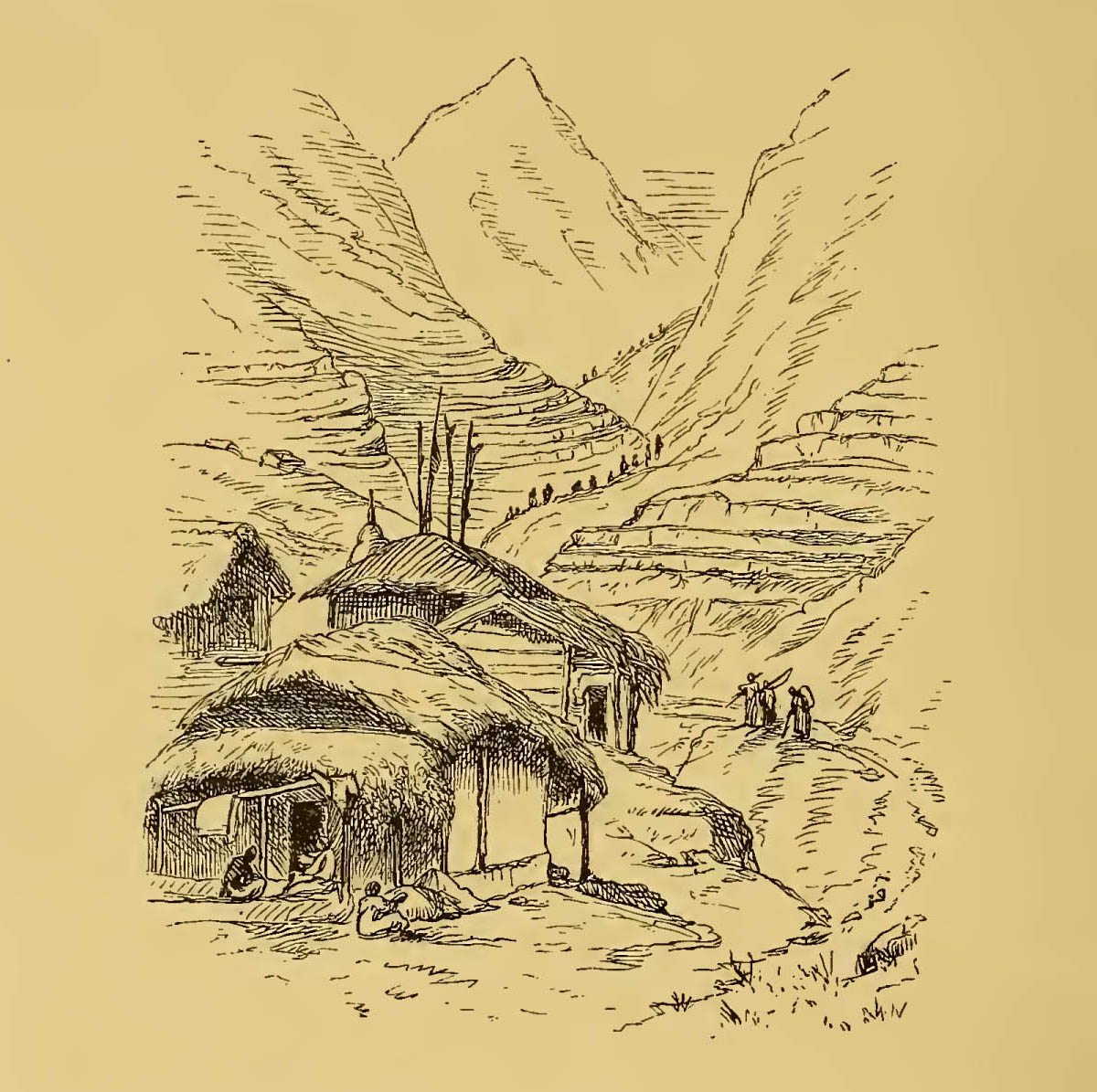

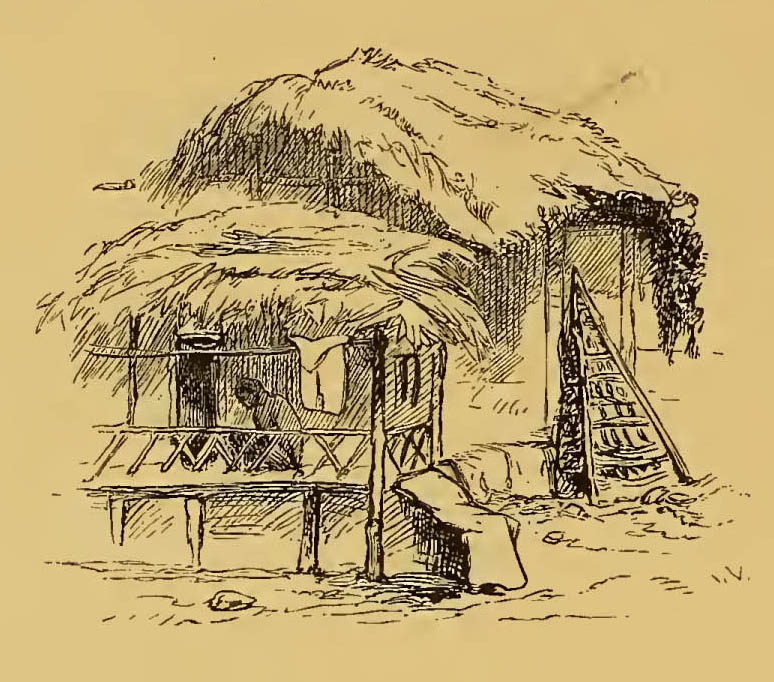

Not only are the people themselves picturesque, but all their surroundings, which add not a little to the beauty of the landscape, with which they harmonise marvellously. Their brown huts dot the mountain slopes, the blue smoke curling through the thatch in graceful wreaths, whilst groups of bright-robed figures, sitting or standing about the doorways, form a kaleidoscope of perpetually moving colour. Although by no means indigent as a rule, they love to live and burrow, in tattered huts, surrounded by every kind of squalor, where they and their numerous progeny — the goats, the sheep, the poultry, and the pigs — exist in almost one common apartment, and lie down together a happy and contented family party. A pig to these hill tribes is not the loathsome, unholy, and unclean quadruped it is in the estimation of the Mahomedan and Hindoo, but their much respected brother, with whom in life they love to fraternise, and in due time, when slain, to eat.

Their abodes form perfect studies for a painter; but perhaps they never look so entirely picturesque as at nightfall, just when, the sun having set far beneath the horizon, the mountains, cerulean blue, are veiled in a dreamy haze. At such times these huts, perched on the ledges of the hill-sides, in all their rich deep colouring and ragged outline, a bright fire burning within the open doorway, form pictures indeed.

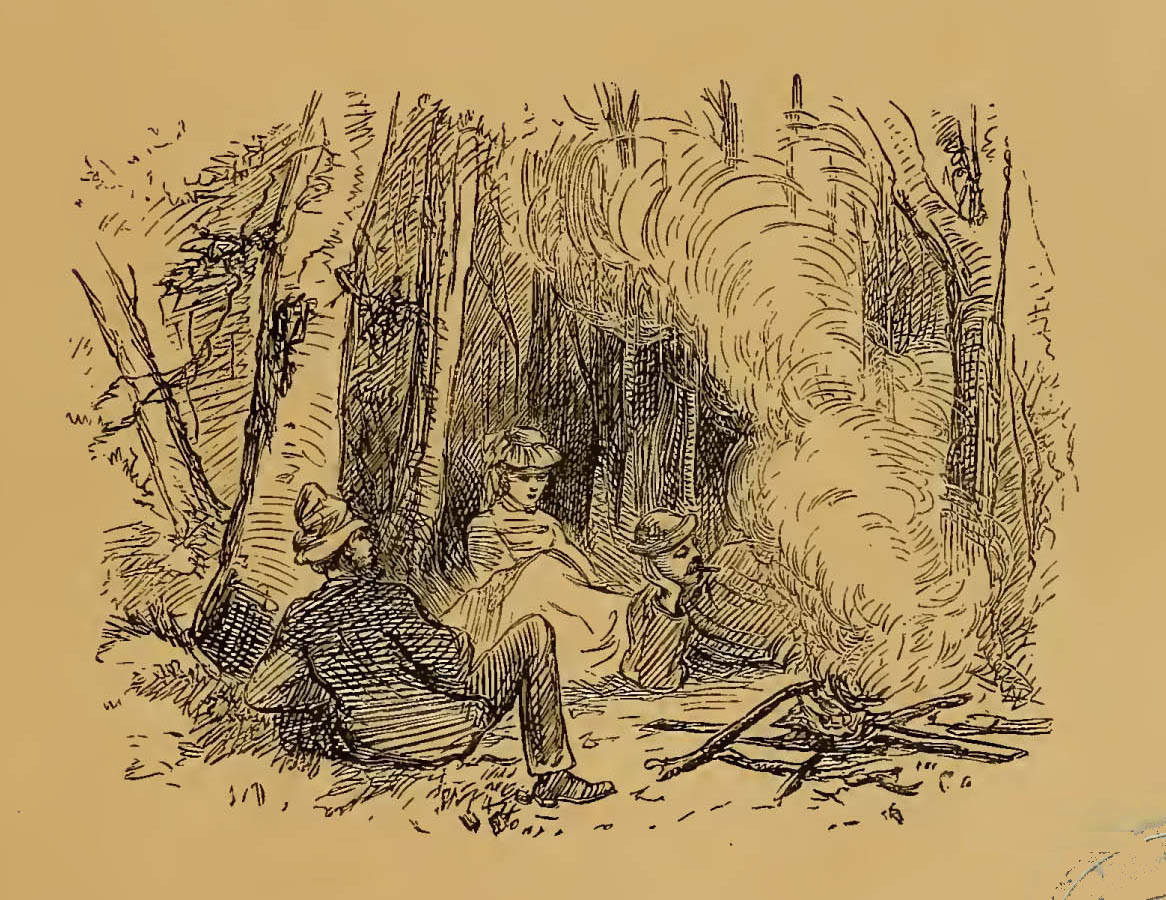

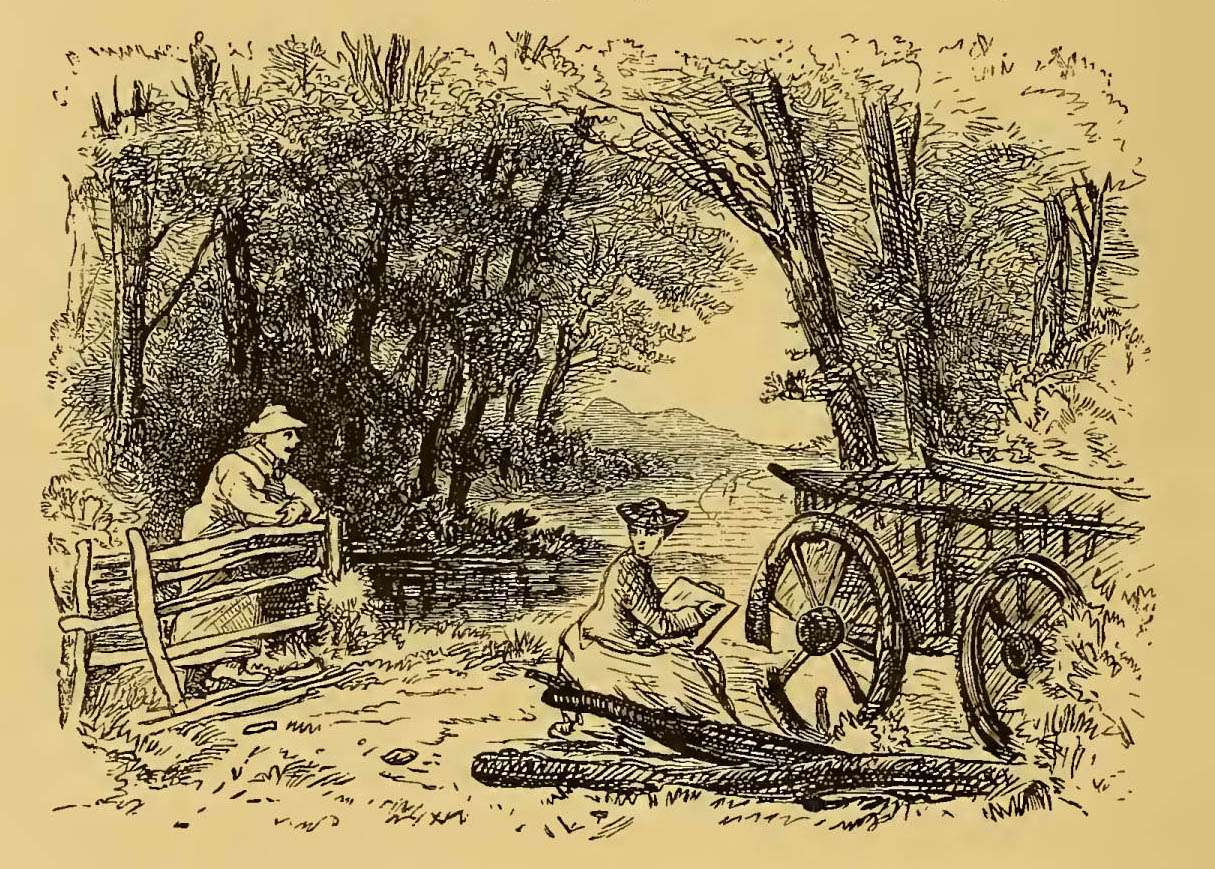

At one period of my Darjeeling career, I haunted the Bhootia village, or Busti as it is called in the language of the hills, which is situated about half a mile from the station; and I may say, in strictest confidence, that I became almost part of it myself, till the very pigs began to recognise and greet me, with a contented sort of grunt, as I sketched the dearest, raggedest, dirtiest of tumble-down tenements, getting to know the dwellers, and their little black-eyed flat-faced children. At first I and my easel were regarded with the utmost suspicion — I must have the gift of the evil eye, they thought. For what other purpose could I desire to set down their ragged homesteads on paper, and carry them away with me, if it were not to weave some spell to harm them? My first appearance therefore amongst these happy simple folk ushered in a reign of terror; but as time wore on, and neither their children nor cattle died, neither did their huts topple over the precipice, they began to look upon me as an inevitable, — a grievance to be borne. Then would they come running up to meet me, as I appeared, a tiny speck on the ridge of the mountains, beneath which their village is situated, fix my easel for me, go to fetch water, sometimes even insisting on holding my colour-box, which was doubtless provoking, as were their comments upon my proceedings and presence generally; but I had no heart to repulse them. Sketching, surrounded by a crowd, even though it be an admiring one, is anything but agreeable, as all know who have tried it, and whispers are perplexing, even though they may be complimentary.

THE BHOOTIA BUSTI (VILLAGE), DARJEELING

HANHART CHROMO IMP

'Ah!' one would say, the spokesman of the party, 'the mem sahib is writing the fence' — they always called it 'writing' — 'and look! now the hole in the thatch.'

And as I dabbed in the colour, another would whisper, 'There! she's writing my old mocassins, which are hanging up to dry' — the representation of any of their personal belongings always appearing to afford them more than ordinary amusement. Then as I threw in another little dab of colour, and they recognised the pigeon, perched on the gable of the hut I was sketching — birds they hold sacred — or any other object of their especial interest, a subdued chorus of 'Ah — a — a — a — a!' would follow from the whole admiring crowd.

But they never really annoyed me except when, in anticipation of my arrival at their village, they attempted to tidy up the outside of their dwellings. Sometimes, whilst I was in the very act of sketching one of their huts, they could be seen all hurry and bustle, scrimmaging here and there with switches and impromptu brooms, sweeping away the delicious rubbish heaps — the accumulation of years — upon which I had set my artistic affections. Once in an incautious moment I happened to tell them I intended some day or other to make a picture of their village all in one. Their delight knew no bounds; and one morning soon after, whilst sitting at breakfast, I was told that several Lepchas and Bhootias were waiting without to see me, where I found a deputation, headed by a stately old Bhootia woman, who begged to inform me 'the village was quite ready, would I come to-day to write it down.'

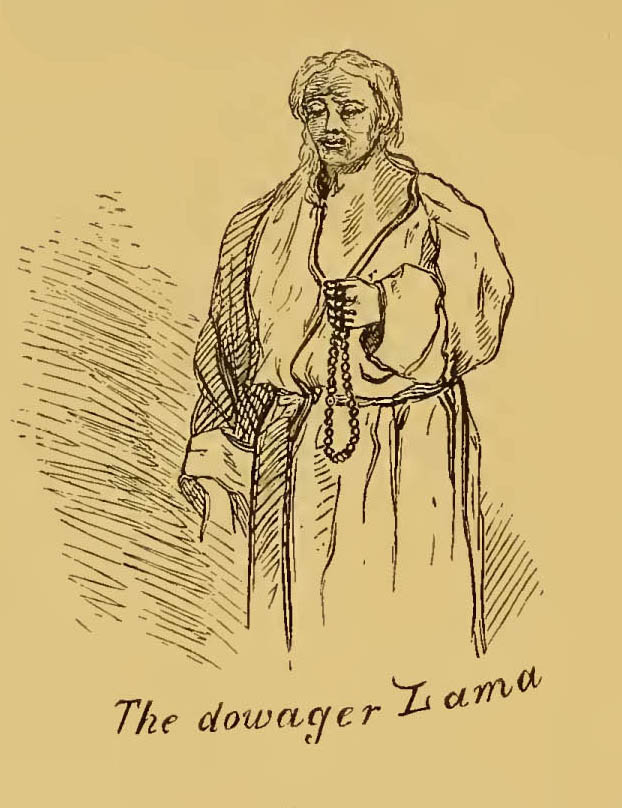

Suspecting some treachery or other, but willing to gratify them, I did start, armed with easel and sandwiches for a long day of it; but what was my horror, on reaching the brow of the hill, to find the village tidied up in earnest, and decked out as for a gala day. Some of the huts were covered with little streamers, and fresh green boughs tied to bamboo stakes; wooden palisades had been mended, and their enclosures swept and garnished; and, as if this had not been enough, they had actually whitewashed the outside of the little Bhuddist temple itself; the old dowager's hut had positively a new roof on, and she herself, decked out in all her finery, was standing at the door, vigorously twirling a 'mani', (praying machine) without stopping for an instant, evidently imagining I could, amongst other wonders, even represent 'perpetual motion' in my sketch.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE CANTONMENT.

AT a safe and respectable distance from all the interesting and picturesque squalor of the village, on the crest of the hill, at an elevation of seven thousand feet above the level of the sea, stand the houses of the English residents; and above these, by several hundred feet again, in a singularly bleak and exposed position, on the narrow ridge of a mountain, the hospital and convalescent depôt are situated: but how the authorities could have chosen such a spot for our invalids is incomprehensible, when the neighbourhood abounds with more sheltered sites, where a fine bracing air can be obtained at the same time.

Here they are enveloped in swooping mists for nearly half the year, which bear down from the higher ridges, or ascend from the valleys on either side. Higher, still higher, in very cloudland itself, rises Senschul, the former site of the military depôt, selected in days when even greater idiocy prevailed, as may readily be imagined when I say that this mountain, protecting Darjeeling from the south-east and encountering the first burst of wind and rain, is popularly called its 'friendly umbrella!' Long ranges of deserted, and now ruined, barracks may still be seen from Darjeeling, on rare occasions, when the clouds open and display them to the astonished gaze of anyone who may happen to be looking skyward.

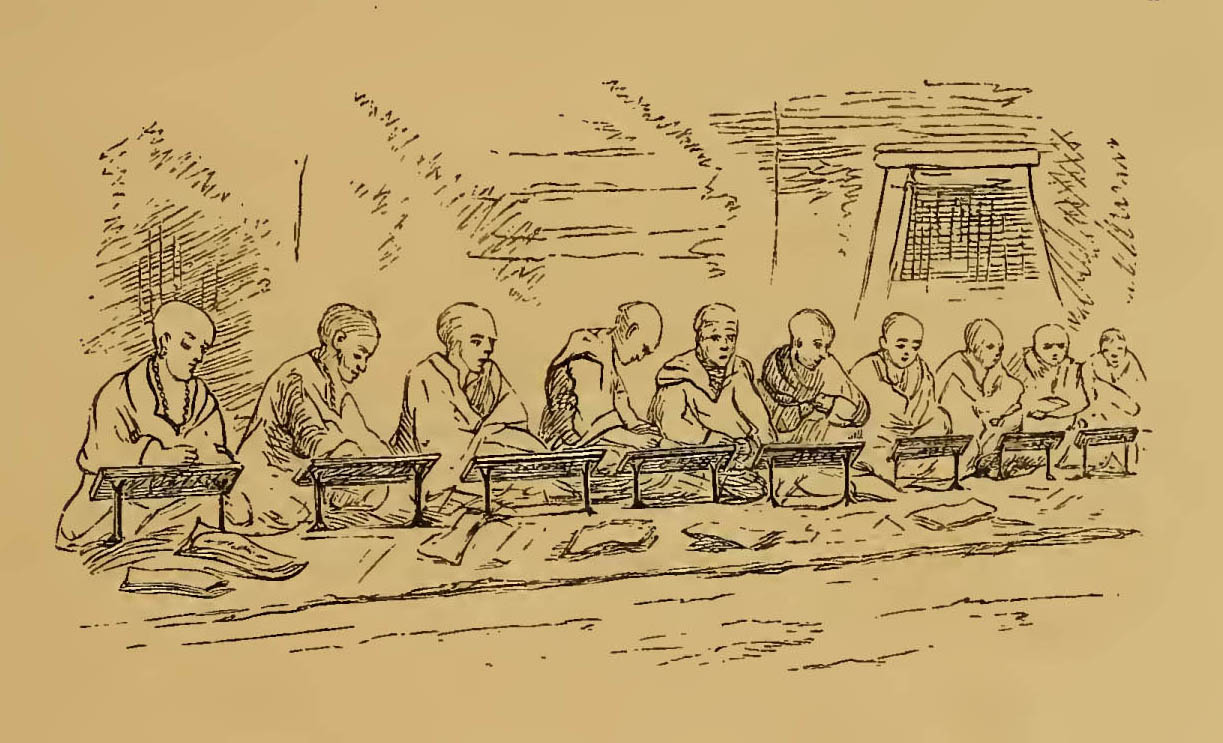

Near the station itself, the mountains are becoming more bare each year, as the forest is cut down for tea-planting; and those who would witness the glorious vegetation with which the steeps are covered, must leave Darjeeling behind, and canter through the woods with a loose rein, heedless of danger and narrow stony paths.