CHAPTER I

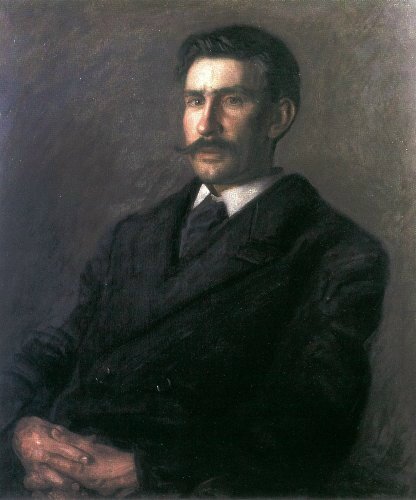

THE FIRST PICTURE IN SPANISH

It was on October 26, 1866, that Thomas Eakins, then twenty-two years old, wrote home to his father the good news that he, Tom, had been admitted at last to study with Gérôme in Paris, adding that he had yet to receive his first letter from home. Later Tom sent the details of his admission and of the hazing he had undergone at the hands of the other students. The day before being admitted Tom Eakins had met Harry Moore; they had exchanged cards and discovered that they had both studied at the Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Harry Moore and his uncle went to see Gérôme and explained how far Harry had come just to study with the great master. They were so convincing in regard to Harry's eagerness and sincerity that Gérôme wrote personally to the Minister and to the Inspector of the School. Even so, when Tom Eakins got his card of admission on a Friday, Harry Moore still had none. However, Tom decided after Friday's hazing in the studio that he had better hunt up Harry and give him some advice about the students. Harry was not in the Latin Quarter but in the American part of Paris near the Arch of Triumph. And it turned out that instead of having a little chamber, Harry was living with his whole family; they had all come over with him. They could hardly believe that Tom Eakins had really been admitted to the Imperial School, and Harry Moore became downcast and fearful for himself. Consequently, the next day the two went together to the school where Tom Eakins was told that Harry Moore also would be accepted. Harry was so afraid he had been refused that he had great difficulty in finding his pencil and paper on which, since Harry was deaf and dumb, Eakins finally wrote the happy word, "admitted." Then they went to Gérôme's together. Since Harry Moore knew very little French, Tom took him around and bought all his paints and things for him. Also Tom explained to the students about Harry's being deaf and dumb, and fortunately they respected his infirmity. Although the official card of admission did not reach Harry until Tuesday, both boys started sketching the day before so they could commence at the beginning of a pose. It was for them the beginning of three years of study in Paris.

Eakins learned the deaf and dumb sign language to be able to talk with Harry Moore. Often Tom Eakins would be invited to the Moores for Sunday dinner. He thought them fine people and enjoyed hearing them talk about all the old families of Philadelphia, especially the Quakers. The fault that Tom disliked in the Moores was their passion for relics. One Sunday before dinner they all went together to the Garden of Plants where Tom particularly enjoyed the elephants, camels and monkeys, especially the little baby elephant; but later in the Museum old Mrs. Moore tried to take some bark from a cedar of Lebanon and the other Moores tried to break a piece off a quartz crystal to send to a son in California. After that they were all closely watched by a guard in a soldier cap who followed them about until they left.

When the Christmas and New Year holidays came around, the Moores invited Tom Eakins for elaborate dinners. He wrote home about the good turkey with potato filling and the absence of cranberries. "You can have no idea of the trouble one has in France to get things done in American style. Mrs. Moore had to show the girl constantly what she must do and watch her closely that she didn't get any chestnuts into the bird, so strong was her desire to do so. The mince pie was to be cooked at a confectioner's about a half mile off. An hour before dinner a little boy came in bearing a portable oven in which the pie was cooking all the time. He wanted Mrs. Moore to see if it was all right."

For his part, Tom Eakins heard Mrs. Moore say she had seen some statuettes in a store window and had not gone in to buy them only because she had feared her French was not equal to the transaction, so Tom bought them for her as a New Year's Gift. He made a date with Harry Moore's sister to go to a Catholic Cathedral on the Feast of Kings.

During his first summer in Paris, Tom Eakins had to escort a visitor from home thru the Louvre, a man who feared he might possibly not appreciate all the old masters and who wanted therefore to take notes. Tom would remark, "Now this picture tells a story; there is an idea in it." At this the guest would call his wife back and say, "Anna, I tell thee there is an idea in this picture," speaking always in such a loud voice that the party attracted great admiration. What the guest managed to get really interested in was a pair of vases which threw sound from one to another with the effect of a whispering gallery.

Eakins lived in Paris with a Monsier Crépon, No. 64 Rue de 1'ouest, to which he had early moved from a hotel. In the fall when Tom had first arrived there, he had written home to his mother:

"Have you been out on the river? It must be very beautiful now with the red and yellow leaves of the trees. The leaves are all changing here too, but they do not grow bright; they only fade and die. Since I left America I have not seen the sun except two or three days in mid ocean, and although the weather is not positively bad, it is far from good. It is always cloudy, sometimes it drizzles a little, sometimes it is foggy. Crépon says the winter is commencing and this is a specimen of it. It never gets very cold here. The Seine does not freeze. The snow is seldom more than an inch deep. We sometimes see such days at home in November. The spring however is said to be very beautiful here and I shall await it with some impatience."

When Eakins wrote letters home from France he took great care to tell those things that would be of particular interest to the person he was writing. His letters to his mother and to Aunt Eliza, who lived with the Eakins family, are charming. In the letter below, the Zane Street School he mentions was the public elementary school in Philadelphia, between Seventh and Eighth on Zane Street, which is between Arch and Market Streets, from which he had gone on to high school.

Paris, July 17, '67

Dear Aunt Eliza:

"I am sending again by mail another batch of stupid grammar stuff and I am sorry that I did not learn dressmaking as well as grammar in my Zane St. school.

"I have never seen a long frock in the streets or a gaudy one, but they all dress very plain. At church the only perceptible difference between the duchess and the laborer's wife is that the duchess is the cleanest of the two. Pews are unknown but each one takes her little praying stool and all sit together. But the washwoman goes home in an omnibus and my lady in a state carriage mounted by flunkeys. These footmen and coachmen dress up like monkeys always with long white stockings and high hats with pompoms in them and they often powder their hair. They are low dogs and very insolent to honest people. They put on great airs and when they stare at me I always laugh in their faces. They are the only men I can never respect.

"The ladies of the court are said to dress very grand and to wear very low dresses which commence somewheres below the breasts but I have never been there. There are not wanting too stories of immorality connected with this court.

"I have seen the Empress a great many times and once when she came to the school I could have touched her had I reached out my arm. Her frock was short so that we saw her legs when she got in her carriage. I have a sneaking idea that her frock was cut bias fold."

Eakins knew well what fashions would mean to his Aunt Eliza. She and his mother, Carolyn Cowperthwaite, were both daughters of Margaret Jones Cowperthwaite, who was very little and plump and lived on Mt. Vernon Street with them. Sallie Shaw, a friend of theirs, remembered it as a very harmonious family. But in youth Margaret Jones, herself an Episcopalian, had married a stern Quaker, and her Cowperthwaite daughters, Eakins' mother and Aunt Eliza, had had a difficult time being fashionable. Eliza would have to take her scarlet crepe dress and jewelry out of the house in her reticule and. put them on at a friend's. Another sister was permitted a few tucks in her bonnet and used to wear a pink bow on the side of it that would be away from her father as they sat in meeting house. Thomas Eakins must have known the tale when he chose to write his Aunt Eliza about the fashions in Paris.

Tom could be charming too when he was writing his Dad, although most of the letters to his father Tom made very practical. However, their house at home in Philadelphia was almost itself a menagerie, so that it is not surprising on one occasion Tom wrote from Paris:

Dear Daddy,

"There is a great big garden at Paris with cages and wire fences in it and these are full of animals, so that it is like a menagerie, only you don't have to pay to go in. There are elephants, lions, tigers, bears, hippopotamusses, rhinocerusses, camels, snakes, wolves, monkeys and a great many other kinds of beasts. I went there last week, and saw some boys throwing bread in to the zebras. A zebra is a horse with stripes all over him so that he looks as if he was painted. There are a great many little birds at Paris that are very saucy. When the boys would throw the bread the zebras would run after it as fast as they could but very often the little birds would be flying off with it before they got to it and this made them very mad and the boys always threw it near the birds on purpose to make the zebras mad. When the zebras would see the little birds flying away with the bread they would turn around and kick at them. Once the boy broke off a very nice little piece of bread and showed it to the zebra for a long time and made him anxious. Then he threw it way off and the zebra ran after but a little bird was flying off with it up above his head when he got to the place. He was so mad at the bird that although it was so high he kicked after it, and he reared up so much to do it, that he kicked himself over and fell down so that all the people laughed at the foolish zebra."

One year in May Tom wrote his father and Margaret about a walk in the Park:

Dear Daddy and Maggie,

"Last evening after dinner I was taking a walk along the garden of the Luxemburg and when I came to the end I saw a crowd of men and little boys and girls and little babies and their nurses. I went up to see what they were looking at and found out it was a man who had a little dog and a monkey.

"The little dog would stand up on his hind legs and dance for a very long time that way, while the man played on a whistle and beat a drum, and afterwards he would be horse for the little monkey and would turn to the right or left and would walk or trot or gallop just as the man would say. When any one gave the man a penny the man would throw it to the monkey and the monkey would catch it in his hand and put it in his little pocket and then turn around and take off his hat and bow to the person that had given it.

"His name was Funny. His master gave him a little sword and then fenced with him for some time, but when he stopped to look round at something Funny hit him as hard as he could and made all the little children laugh. One time his master said, "Funny, how do the naughty little children do when they don't want to go to school," and Funny put his little hands over his eyes and hollered as loud as ever he could and then all the nurses laughed and some of the children too but not all.

"Funny had a little fiddle to play music on but it was not as good music as Fanny makes on her piano. When he was done his master said he had not played well and told him to give him the fiddle, but the monkey gave it to him over his head and he had to say it was a good tune and ask him please before he could get it away from him. Funny played the tambourine too and rung a bell while he galloped around dog-back and when he dropped his bell and his master told him to pick it up without getting off of the dog's back he reached out his long tail and picked it up with that. At halfpast eight o'clock it was beginning to get so dark that Funny couldn't see to catch the pennies and so the man stopped and little Funny jumped up into his master's arms and kissed him and they went away. The little dog wagged his tail and barked and ran on before, and I hope they had all a good dinner after they got home."

Tom's oldest sister Fanny, Frances Eakins, loved music all her life; Margaret (Maggie), the next in age, was a close companion for Tom; Caroline (Caddy), who completed the family, was a child with toys when he was studying in Paris.

By November of 1867 Eakins was writing Mommy and Aunt Eliza that he had no fashions to tell about just then because the people were thinking more of bread and prison than of fashion.

"So I will tell you about my housekeeping for I have again moved. My first studio was on the pavement one step below the ground paved with brick and the walls with dark bluish color. It was a nice large studio and I thought I could live there very well, but it was impossible to keep it clean. I bought a big broom but the way the dirt would stick in those bricks was a caution. I had spread a piece of carpet down by my bed to tread on for if I trod on the bricks I had to go wash my feet. Then I had to be very careful to tuck in the bed clothes well at night for if they touched the bricks they were soiled too. One day I found that the wall had the same effect on them and then I made up my mind to wash the wall where my bed was. Sculptors had had my studio before me and a sort of dust had settled all over the wall. It took me nearly all day to scrub a place big enough for my bed and I think that after I had worked for about two hours right hard and had skinned my little finger that if any one had come to me and offered to clean house for me and all for nothing I would not even have got mad. Crépon came in and put up a big curtain all around my bed for me so that I was not on the whole very uncomfortable, but my trouble after all was to keep dry. I thought it would be very easy with a fire, but the fire would go out sometimes at night or I would be away all day and although I never got a cough or other sickness I was apt to have a cold in the head. Crépon's little baby got sick and the doctor told him he must get away from his quarters to an upstairs place, that besides the danger to his wife and child he might find himself some day with rhumatism. Crépon told the doctor how he kept fire going all the time but the doctor said that that did not do much good although some one told him no one ought to live on a ground floor. When I heard all this I began to think of myself and concluded I had better leave my quarters too. So I have taken in place of my old studio an upstairs one in the same building. I am now rather more 64 than 62 rue de 1'ouest. Crépon is looking around for a new house but has not yet been as lucky as I was. Having a child it is very hard to rent a room in Paris. Children interfere with the comforts of close neighbors and children seem to have no business to be in Rues for it is not the fashion. They should be given to common ignorant strange women to nurse, one of whom has just been sentenced to prison for killing little babies and keeping on charging for them weekly months after their death when she pretends they are just dead.

"The place I am in now is perfectly dry and comfortable. It has a nice wooden floor of oak which may be waxed if one likes it but I'm sure I'll never take that trouble; but what is so good about it is that when one takes the broom the dirt dont stick fast but slips easy along the floor and is put all in a pile. The studio is not so large as the other one but plenty large enough. Over the entry is a little room just big enough for my bed and then another place for my clothes and writing materials. I go to bed up a little ladder and there is a door and balcony which will prevent me from falling down into the studio if I should take to sleep walking. This little room is papered and I can easily keep my bed and everything perfectly nice."

In a previous letter Tom had even made drawings of his furniture, including the enormous bed with heavy curtains for all four sides, curtains hung from a substantial frame and draped over the footboard in the drawing. All French bedsteads seemed to have curtains which were an advantage for those who didn't have to get up early and Tom would like to know when his mother would ever be up. if she had long curtains to her bed. As for himself, he was glad he was living across from the old palace of Luxembourg with an arsenal or something right back of his place, because the soldiers from both with their trumpets and drums managed to wake him up at the right time every morning. He was careful to include a drawing of his bureau so Aunt Eliza would rest easy in her mind about his having a place to put his clothes. However, the bureau was supplemented by wooden pegs on the wall with a curtain to pull over his things to protect them from the smoke from the fireplace. The drawings included the wash stand with its pitcher and basin. He was delighted that there were no bugs and not even any fleas.

Also during his second November in Paris Tom wrote:

"Dear Father,

"I thought my studio down stairs would do but not keeping dry I have changed to one upstairs which costs however 200 francs more although considerably smaller, and my rent is 850. I received your cheque for 1000 francs for which I feel extremely grateful and I will be careful not to waste any of it. I will soon send you another account of my expenses. I am right well and hard at work but in the dumps the last of the week, for I made a drawing on my canvass according to Gérôme's directions for Wednesday and then he said not bad, that will do, now I will mix your colors which you will put on. I have not been able to make them gee together and have got a devil of a muss and will get a good scolding tomorrow morning.

"Crépon has furnished my studio completely with Saute's things and some of his own as he will not probably have room for them when he takes an up stairs place. He even had a bedstead so that all I have bought is my bed mattress and covers. I am perfectly comfortable and would be happy if I could make pictures.

"About that I am not so down hearted as I have sometimes been. I see much more ahead of me than I used to, but I believe that I am seeing a way to get at it and that is to do all I see from memory. I believe I am at least keeping my place in my class and have made friends with the best painters. Gérôme is very kind to me and has much patience because he knows I am trying to learn and if I stay away he always asks after me and in spite of advice I always will stay away the antique week and I often wish now that I had never so much as seen a statue antique or modern till after I had been painting for some time."

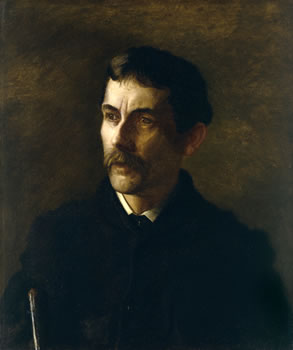

Samuel Murray, the most intimate friend of Eakins during the last twenty-five years of the latter's life, remembered that Eakins had always said his father had told him when he went abroad to study, "You learn to paint the best you can, Tom; you'll never have to earn your own living." Nevertheless, while he was abroad, Tom Eakins sent his father meticulous detailed accounts of his various expenses. In the spring of '68 one such itemized list contained the purchase of a copy of Rabelais for 1.75 francs. Eakins was not a reader, and there is no way of knowing if he read much of this book after he had bought it.

However, if he did read the book by Rabelais, admiration for that monk's great knowledge of anatomy would have predisposed Eakins to take well in his stride the absence from Rabelais of all Victorian standards of modesty. With his own knowledge of anatomy Eakins would, with the rest of the world, have enjoyed the manner of Gargantua's birth; with his knowledge of French, Eakins must have smiled at the naming of the giant from the phrase "Que grand tu as"; and Eakins must have been glad for his Latin when he bought Rabelais, since so often the point of Rabelaisian joking lies in the small Latin comment that ends a story. It is of interest that when he was forty-six Rabelais fled from his convent of Fontenay where thru fifteen years he had laid the foundations of his great learning, fled from the persecution of fellow priests who feared the effect of the Latin and Greek he was learning. Eakins could not have foreseen that when he himself was forty-four he too would be forced out, in a manner that seemed to him very unfair, from a place of learning that had meant much to him thru years. Except for the New Testament in the Latin translation, Eakins read very little.

His expense accounts shed amusing light on the way Eakins lived in Paris.

"Monday night Aug. 3d '69

"Dear Mommy,

"My accounts I let run on without setting to work at them for a long time but to night Bill and I had a settling between us and that gave me a good chance to send you my expenses. But I forget where I left off when I last sent you my accounts so I will commence a little way back and you will see as where to commence.

| Kindling and charcoal (my half) | 1.00 |

| Hammer and broom and tacks (ditto) | 1.80 |

| Head and a hand plaster casts | 5.00 |

| Pair of shoes | 20.00 |

| Photograph of Gérôme | 1.00 |

| Opera of Martha | 2.00 |

| Another photograph | 1.00 |

| Hair cut | .50 |

| 4 Photographs life studies | 8.00 |

| 1 group of students | 1.50 |

| 10 postage stamps | 8.00 |

| Canvasses sent from Crépon's old studio | 5.00 |

| Shoes | 12.00 |

| Saturday April 17. I draw from bank 300 francs having only 25 in pocket | |

| Rent of chamber | 69.00 |

| Colors and brushes | 2.00 |

| Photographs from nature | 4.00 |

| " " " landscape | .80 |

| Colors and brushes and canvas Chenoz' bill | 23.00 |

| Washing from April 1 | 10.00 |

| Petroleum and chimney | 2.00 |

| Cravate | 1.80 |

| Photographs | 4.20 |

| Comic opera the daughter of the regiment | 1.50 |

| Palette knife | 1.50 |

"Saturday May the 8th 1 draw from the bank 300 Fr. thinking I was most run out but find afterwards money in my drawer.

"Such is my entry in my book but I found out tonight that I had not remembered to put down a bill for a suit of clothes I got. I remember I went up to see Homer that Sunday that I paid the bill and so it must have been about that time. So I guess 1 drew out the money because I would not have enough to pay that bill and having the money forgot what it was for. I can't find the bill either but I know it was about 135.00

"I remember now that when I first went to pay the bill his wife couldn't tell me what it was and told me to wait till he was over this side of the river and he would bring it that must be how I paid it when Homer was here for it must have been about June 6 when Homer was here but I remember wearing my good clothes in May but I will leave my account now as I have set it down in my book as if I paid it when I got the clothes.

| Coat vest pantaloons and darning old ones | 135.00 |

| Circus | 1.00 |

| Shinn's catalogue and sending it on | 2.75 |

| Modeling wax and tools | 4.75 |

| Saloon extrance | 1.00 |

| Chamber | 55.00 |

| Waiter | 5.00 |

| Plaster cast anatomical figure and Houdons cold girl | 8.00 |

| Du Bouchet 8 plugs | 160.00 |

| Washing | 1.00 |

| Petroleum | .80 |

| Du Bouchet still another tooth | 20.00 |

| Circus | 1.00 |

| Circus Napoleon the Japanese | |

|

Friday June 4, Having in pocket

only 26 fr. I draw out 300. There remains 2053.55 ---------------------------- | |

| On Account of Poole | |

| A Postage stamp pour 2000 fr. | 1.00 |

| 2 pairs kid gloves | 9.50 |

| 2 more pairs kid gloves | 10.00 |

| Poole was down in the country and got me to attend to his things. He will pay me when he comes back. | |

| Circus 2 and Japanese once | 3.00 |

| Grand Opera Faust | 3.00 |

| Brushes Colcombs | 13.50 |

| Colors at studio | 3.00 |

| Canvass | 1.75 |

| Monday I draw from bank 300. It was smart in me to put down Monday instead of the day of the month. However it don't matter much. | |

| Straw hat | 22.00 |

| Cure Sauvage Bill and me to the Japanese | 5.00 |

| Postage stamps | 8.00 |

| Hair cutting | .50 |

| Charcoal | 1.00 |

| Fourth of July (Barometer Aunt Eliza's money) | 100.00 |

| Chamber | 60.00 |

| July 11. I again draw 300 fr. | |

| Showing Mrs. Schmitt around | 20.00 |

| Canvass and brushes | 11.00 |

| Big palette | 5.00 |

| Bill at Chenozs' | 61.00 |

| July 26. I again draw 300 to meet rent bills. | |

| Rent of chamber and water | 60.00 |

|

Rent of my studio for the three months up to the 15th of October 127.75 and 2.25 to the doorkeeper | 130.00 |

| Pincers to stretch canvas | 1.60 |

| Loan to Bonheur | 40.00 |

| I could write you a whole French novel about that which I will do some time or other. He will pay me back in September or Oct. | |

| Twice to the circus | 4.00 |

Tom Eakins seems not to have spent very much money for travel thru Europe. He was there to study seriously with Gérôme, and he spent his time doing that. However, during the summer of 1868, his father and sister Frances came to Paris in July and Tom travelled with them thru France, Switzerland, and Italy (to Florence, Rome, Naples) and to Munich in Germany. His father and Frances were back in Philadelphia by September, and Tom himself was there for Christmas, spending two months at home before returning to Paris in March. The Crowell family remembered a walking trip on the continent; Will Crowell, Bill Sartain and Tom Eakins tramped thru Germany, Switzerland, and perhaps France. They would start out with their knapsacks, separate, go different ways and meet again later on. The only record of the trip is an undated letter from Switzerland, written to his father from Zermat by Tom. He thought Zermat

"the most God forsaken place I ever saw or hope to see. The people are all either cretins or only half cretins with the goiter on their necks. They live in the filthiest mariner possible the lower apartment being privy and barn combined and they breed by incest altogether. Consequent goiters and cretins only. If I was a military conqueror and they came in my way I would burn every hovel and spare nobody for fear they would contaminate the rest of the world. When you ask them a question they grin and make idiotic motions. Jesus Christ on the cross are at every 50 yards with lots of blood and agony. We saw a congregation waiting for church. This is a week day. They go to church every day. The women were laughing as usual and picking the lice off the children's heads till the priest came. The hats the women wear are as stupid as possible, a band with gold or silver edge surrounding the crown. They all have big faces and the heads run lower than those of the flat head Indians but don't stick out behind like theirs. They are dirty as they can be and so have become contented as they can never become dirtier. The women aforesaid are not contented no more than the men. Their minds are not even capable of this sentiment. I mean to say their ancestors were contented to be as dirty as possible and they are as dirty as possible only because their ancestors were and they never would think of a change even if no trouble to make. Even the children are frightfully ugly. When a woman comes along leading a cow or sheep of ordinary intelligence you ought to see how intellectual looking and spirited the animal is alongside of the woman by contrast. They stink their houses stink worse, the water of the valley stinks, and the valley itself stinks except in a few places for instance the big French hotel we are now in. Out in Poland and down in Italy they have the cholera. It is to be hoped it will get up some of these valleys. An earthquake some years ago was a godsend in destroying half of them. The rocks thrown down the mountain sides are the biggest loose rocks I ever saw almost young mountains in themselves. We meet of course crowds of Englishmen. The only bearable ones are those who have lived in Australia a long time and were fetched up at Cape of Good Hope in Africa or the little girls too young to be prudish and English. The latter might be tamed if got away from the disagreeable associations, but it would not be worth the trouble unless to one who could find neither an American, French Italian Spanish or Chinese. Now it is raining worse then ever and the hotel is full of English. They are great hogs, so different from the French. …Chamonix is in French Switzerland nothing like this dutchwalley we're in now."

The three travellers had come from Geneva to the eastern end of the lake of that name, and here they had stayed all night at Villeneuve; then by rail, part way at least, they had continued southeast to Martigny. The third day they had "got to the top of Col de Baume by walking on our way to Mount Blanc". The fourth day they had walked to Chamonix and after dinner had gone up to the big glacier, Mer de Glace, which they had crossed, getting down by nine o'clock next day and coming back to their starting point, Martigny, by another beautiful route. It was necessary to loaf a day at Martigny, for both Bills had sore feet. After the day of ease Tom Eakins, Will Crowell and Bill Sartain went by rail to Visp and on foot to Stataen where they slept the night. The next day they reached Zermat and were forced by rain to stay there. Eakins wrote his father that "Geneva and its lakes and mountains are beautiful and as far as French is spoken so are the people, as well as intelligent", and then Tom added that frank opinion of Zermat.

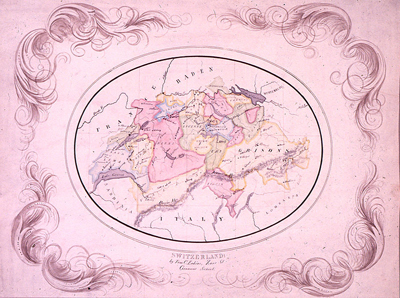

Tom was blessed with a father who believed in him. Even when Tom was a little boy, his father, Benjamin Eakins, had saved his drawings and had believed the lad had talent. One of the things so treasured was an oval map of Switzerland divided into Lucerne and other districts painted pale green, pale blue and pale yellow. The printing is very straight and accurate, there is e decorative feather scroll border in tan-gray, and the map is signed "by Tom G. Eakins, Zane St. Grammar School." The C is for Cowperthwaite, his mother's maiden name. The map is a remarkably good piece of work for a child, and on it appear Martigny and Villeneuve, the latter as Volleneuvre. When he was in his teens Tom had made with white chalk or paint on manila paper a drawing probably copied from a lithograph of a dozen or so figures grouped around stone ruins. This he had signed "La Bum de Eakins". At the bottom of an accurate mechanical drawing of a worm screw Tom had sketched amusing figures of little men in odd poses. A perspective drawing of a lathe done when Tom was sixteen – his father, Benjamin Eakins, treasured such things and for the rest of his life backed Tom in his resolve to be a great painter.

|

| Map of Switzerland |

| ca.1856 |

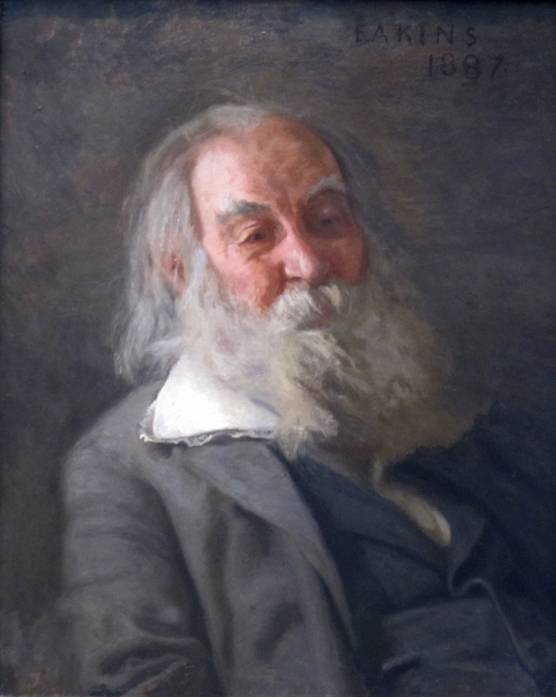

Always Eakins was glad that he had gone abroad to study, particularly that he had had the chance to study with Gérôme, for Gérôme was a lover of great painting and a despiser of mediocrity. He wrote in the preface for his life and works by Hering: "It is austere and profound studies that make great painters and great sculptors; one lives all one's life on this foundation, and if it is lacking one will only be mediocre". He himself has been praised for his ability to portray motion and for his great success in the use of foreshortening. But in one respect Eakins and Gérôme had little in common. Gérôme travelled often – in Egypt, Arabia, Palestine, Turkey, Russia, Italy, Algeria, Morocco, Spain. Nearly two hundred of his things are travel pictures. Eakins after nearly three years of Europe swore that if he ever got home to Philadelphia again, he'd stay there the rest of his life, which is what he did. However, both Thomas Eakins and Gérôme, who was of Spanish descent, admired the Spanish painters, particularly Velasquez, Ribera.

Much as he sincerely admired the genius of Gérôme, Thomas Eakins must have found uncongenial the elaborateness of Gérôme's establishment, the glass doors hung with Persian fabrics, the lavish curios, the marble staircase with the massive red and shining cobra coiled about the newelpost, the marble walls covered with bronzes, masks and plaques all the way up to the fourth floor which was reserved by Gérôme for studios and for his own private apartment. To offset the jarring of such ornateness, there was his love of animals, a love which equaled Eakins' own. Two favorite greyhounds of Gérôme's which he modeled in red clay appeared in his pictures. He kept hunting dogs and fine horses and was an excellent horseman. He made studies of camels and monkeys. But the animals Gérôme most enjoyed sketching were the lions; such nice lions he made them, especially when they were sleeping. His notebooks are full of lions and lion cubs in ingratiating poses, one forepaw flipped over the other, or head resting on forepaw dog-fashion, or head prone sideways on the ground. In the painting, "Love, the Conqueror", a whole cage of lions and tigers are succumbing to little winged Love, are rolling over and licking his feet. It may have been his love of lions which led Gérôme to paint "The Christian Martyrs", though in this picture of the early Christians being sent to a bloody death in the Circus Maximus he could scarcely have made his lions other than ferocious. The impossibility of putting into such a picture a cuddly lion in an endearing pose is somewhat understandable. Many of Gérôme's paintings are classical in subject; he particularly liked gladiators, which gave him an excellent opportunity to work on anatomy.

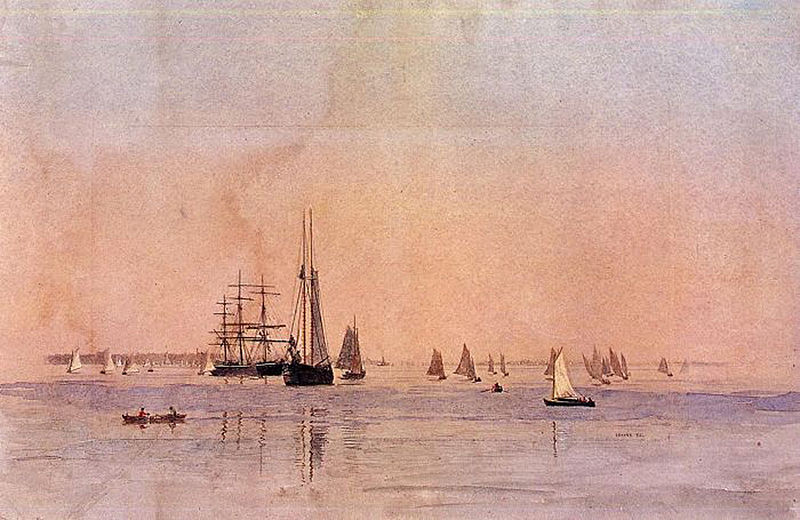

Some time after he had gotten home again to America, Thomas Eakins sent a watercolor back to France, to Gérôme. His former teacher wrote Eakins appropriate thanks for "A Rower" and sent also a telling criticism: The rower was very well drawn piecemeal but the figure as a whole lacked movement because it was arrested in the middle of a stroke; hereafter Eakins would please paint his rowers in two positions only, either at the very beginning of a stroke or at the very end of one. Gérôme was pleased to praise the general quality of the painting, the firmness and lightness of the sky, the well planned background, the charmingly executed water, exactly right, which he could not praise too much. Eakins sent Gérôme another watercolor in which the rower was bent well forward and the oars were well back, and for this he got from Gérôme the unstinted praise that it was altogether good.

Perhaps as a result of Gérôme's enthusiasm for Spain and for the Spanish painters, Tom Eakins and Harry Moore spent some time in that country after they had left Paris and before Eakins left Europe for good to come home to Philadelphia. Eakins had not been well and he wanted to go where there was sun. He considered Algiers but went instead to Madrid in the center of Spain and from there down to Seville almost in the southern tip.

"Fonda del Peninsular Madrid

Thursday Dec. 2, 1869

"Dear Father,

"I suppose and hope you got my last letter telling you of my progress my determination to come hone to stay, early this summer. I left Paris Monday night in a pouring rain of course. All my friends came to see me. If it had not been winter time and if I had not known and feared the Atlantic voyage, not being well, I would have come home straight, but since I am now here in Madrid I do not regret at all my coming. I have seen big painting here. When I had looked at all the paintings by all the masters I had known I could not help saying to myself all the time, its very pretty but its not all yet. It ought to be better, but now I have seen what I always thought ought to have been done and what did not seem to me impossible. O what a satisfaction it gave me to see the good Spanish work so good so strong so reasonable so free from every affectation. It stands out like nature itself. And I am glad to see the Rubens things that is the best he ever painted and to have them alongside the Spanish work. I always hated his nasty vulgar work and now I have seen the best he ever did I can hate him too. The best picture he ever made stands by a Velasquez. His best quality that of light on flesh is knocked by Velasquez and that is Rubens' only quality while it is but the beginning of Velasquez's. Rubens is the nastiest most vulgar noisy painter that ever lived. His men are twisted to pieces. His modelling is always crooked and dropsical and no marking is ever in its right place or anything like what he sees in nature, his people never have bones, his color is dashing and flashy, his people must all be in the most violent action must use the strength of Hercules if a little watch is to be wound up, the wind must be blowing great guns even in a chamber or dining room, everything must be making a noise and tumbling about there must be monsters too for his men were not monstrous enough for him. His pictures always put me in mind of chamber pots and I would not be sorry if they were all burnt.

"Tuesday afternoon at 2½ o'clock we started into Spain. It was still raining. The night was very cold in the mountains. At daylight we were crossing mountains with snow covering them all. At 10 minutes of seven we commenced descending. The sun got up in a clear sky a thing I had not seen for a very long while and at half past nine we were in Madrid. I was pretty weak and sick from my diarrhoea but the sight of the sun did a great deal to cure me and now I feel right well and almost as strong as ever. The sky here is a very deep blue the air is dry mountain air and the temperature 40 Fahrenheit. The people all cover the nose and mouth and wrap themselves very warm and I do the same thing. My appetite which I had lost entirely is as entirely come back again. Tomorrow night I will start to Seville where I will try to stay some time. Madrid is the cleanest city T ever saw in my life. The ladies walk the promenades with long trains like in Philadelphia and just as rich dresses what is never seen in Paris, and I don't think they are much more soiled when they come home than if they had been to a ball. The hotels are clean the privies are large commodious and built on the American not French pattern and the floors are everywhere covered with carpet or thick matting even in the picture galleries. The peasants and muleteers have very bright pretty colored dresses sometimes though they are dressed entirely in skins with the wool left on or worn off by age. There are a great many ink shops in Madrid and where a man sells a great many kinds of things he still advertises and pays most attention to his ink. What in the world the Spaniards want with ink I don't know unless for their generals to write pronouncements and proclamations with. I went to church this morning to hear mass. The music on the organ is the queerest I ever heard. It is the quickest dance nigger jig kind of music then its echo in the distance. Then another jig and it comes so sudden each time or you can't get accustomed to it. The whole cathedral floors are covered with thick matting and there are no seats. The people all keep on their knees men and women and from time to time fell their face on the ground like a Hindoo sticking the backside up in the air and then back on the knees again. Friday afternoon. The ladies of Madrid are very pretty, about the same or a little better than the Parisians but not so fine as the American girls. A good many of them are fair but the proportion is not so great of fair ones as in America. The country women are often coarse with that ugly hanging of the eye that is often supposed to represent the whole Spanish type. I have been going all the time since I have been here and I know Madrid now better than I know Versailles or Germantown and tonight I leave for Seville. I have seen the big work every day and I will never forget it. It has given me more courage than anything else ever could. The cooking is very nice here with one exception I don't like stinking fish cooked in garlic egg and oil with fresh lemon juice squeezed over it although the Spaniards even the delicate ladies seem very fond of it. The Spaniards as far as I have seen them seem to be a very good average sort of people, with good ideas or none at all.

"I would not tell anyone about my coming home. Bill Sartain thinks best too. I would not want any one to make plans hanging on my coming, and I do not care for Schussele or the young artists to know of it."

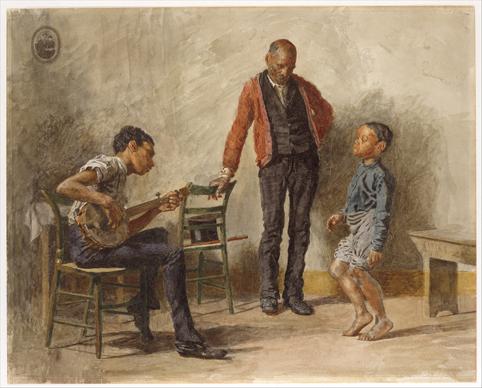

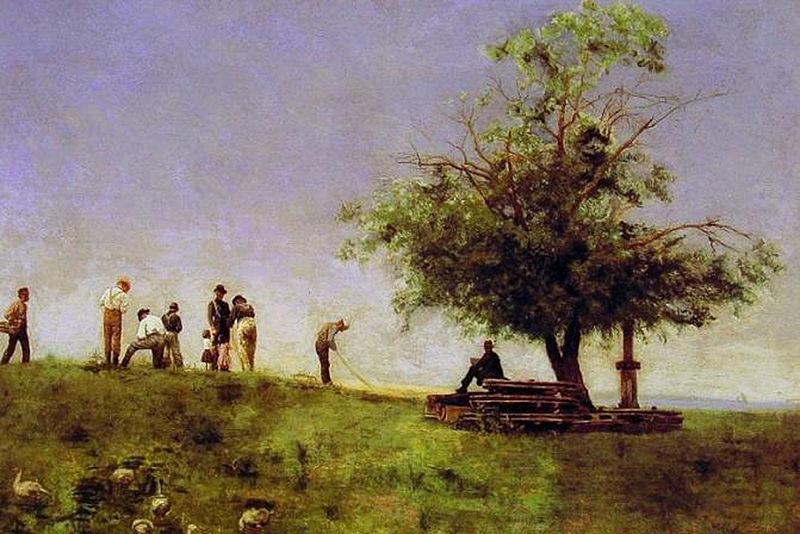

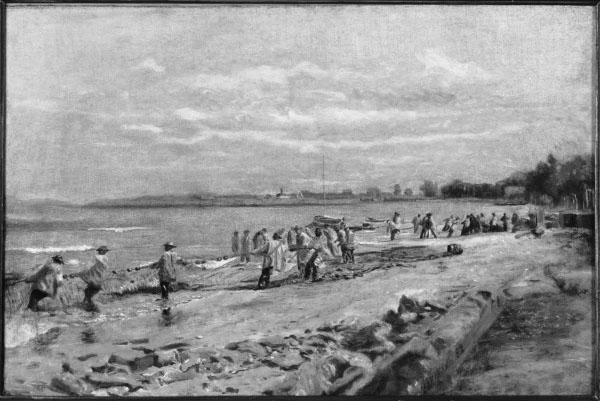

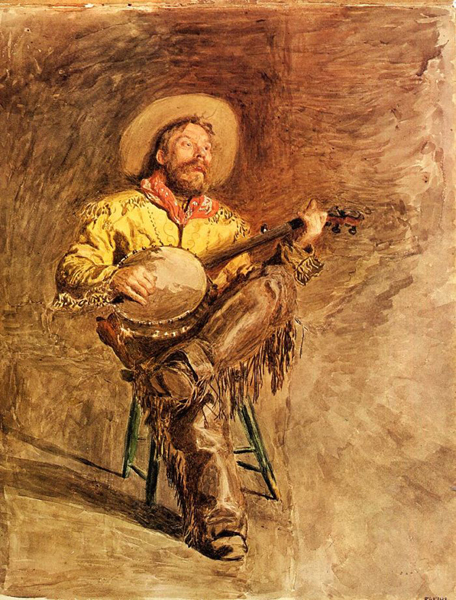

Once settled in Seville, Eakins was soon joined by Harry Moore with whom he made a habit of tramping the countryside late afternoons, getting back to the pension in time for dinner, after which the two would sit by the dining room fire and converse in the deaf and dumb language which both of them knew. They liked the Spaniards, kind and courteous people who were careful not to let their children show too much curiosity at the performance of those who used the sign language. Eakins had also studied Spanish. Will Sartain arrived in time for all three of them to enjoy some gallops on horse back during the spring. The southern climate agreed with Eakins and he felt on top of the world. He was fascinated by the Spanish gypsies and street dancers and quiet gentle-looking bull fighters, and he wanted to paint them. However, with the latter he got no further than indicating on the wall before which dancers are performing in his painting called "Street Scene in Seville" the elements of a bull fight.

|

|

This "Street Scene in Seville" is the first really ambitious painting in oils that Eakins ever did. Over five feet in height and nearly four wide, it presented the problem of color under the warm southern sun. Eakins had approached his training as an artist by the route of drawing, and he had found in Paris that the problems involved in the use of brilliant color were difficult indeed. About Christmas time in Spain he had painted head and bust of seven year old Carmalita Requena, and it was she and her parents who posed in their usual role of street dancers for this larger painting. Carmalita strikes a pose with the toe of her left ballet slipper well pointed forward, and she shakes tambourine and castanets. To Carmalita's left her mother sits on the drum she is tapping; to Carmalita's right her father stands, playing one of the horns, a cornet probably, while above his right shoulder a woman holds a child to the grilled window to watch them. In the upper right hand corner of the picture is a rectangular view of sunlit sky and palm tree and walls beyond the wall. Thomas Eakins did the painting with mixed feelings of pleasure and pain, pleasure because of the conviction that he was no longer a student now but was getting started on his career as an artist, pleasure because he could work with beautiful models right in the sun on the roof of the hotel. But he found the painting took weeks longer than he had expected it to. He could not yet work fast, and his inexperience made it necessary to keep changing his calculations drastically. Eventually it was finished. He was back in Paris in June and home in Philadelphia in the States by July 4.

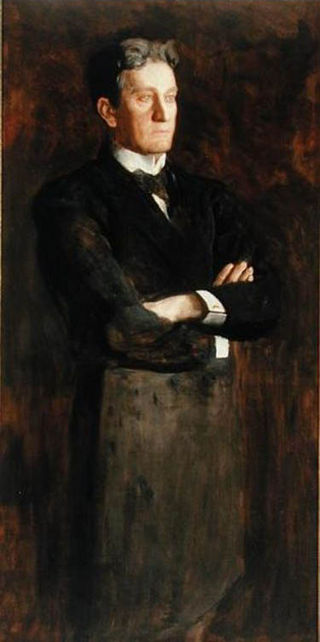

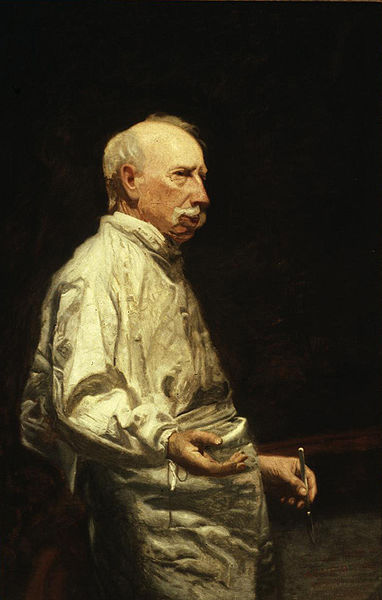

Harry Humphrey Moore remained in France for most of his life, but when the First World War caused the request in 1916 for all foreigners to leave, Harry Moore in a dark French beard came back to Philadelphia and looked up Thomas Eakins fifty years after their original meeting in Paris. Eakins was still living in the three and a half story red brick house at 1729 Mt. Vernon Street in Philadelphia to which he had returned at the end of his student days and where he had found that his father had fitted up the third floor back as a studio for Tom.

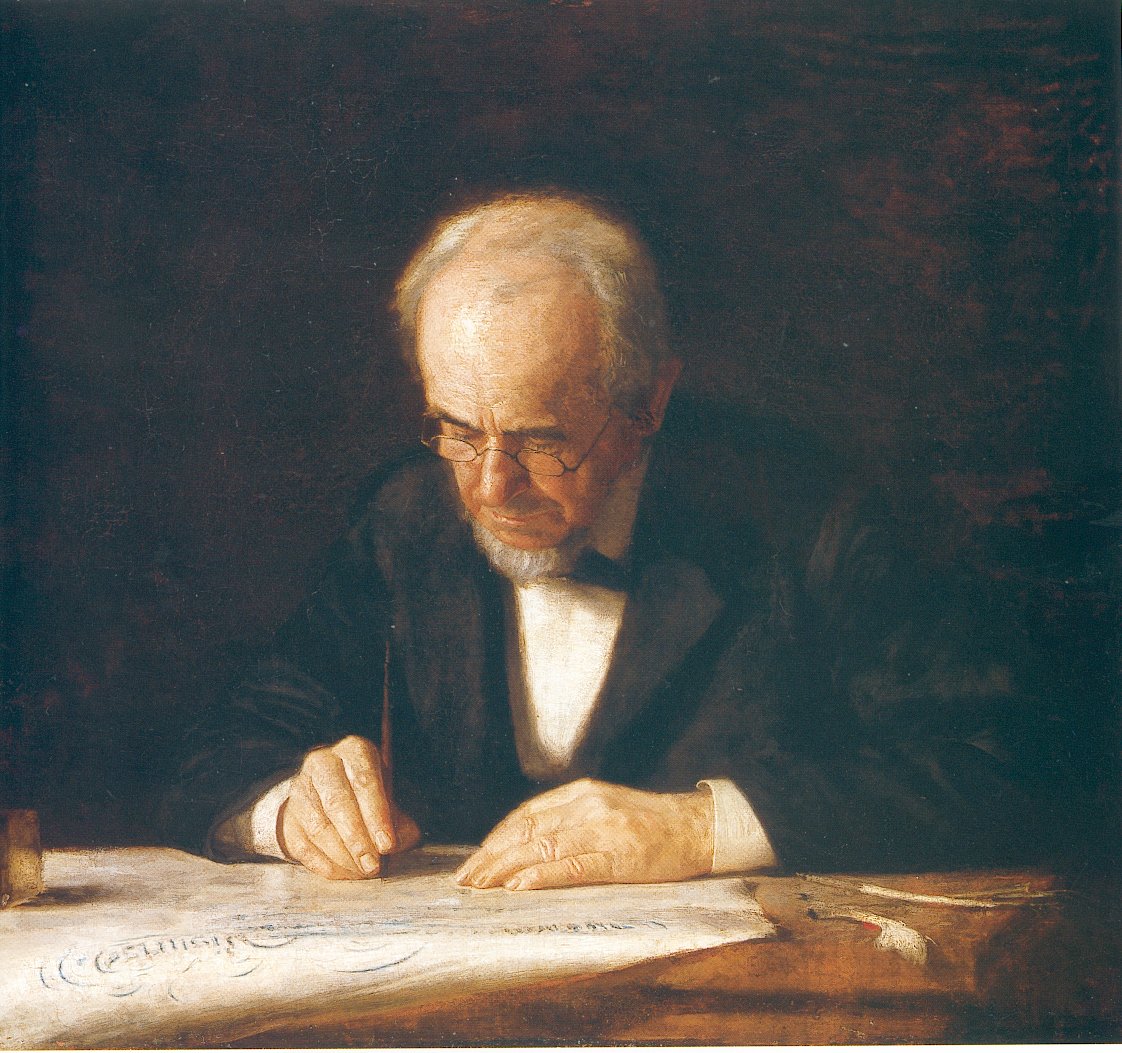

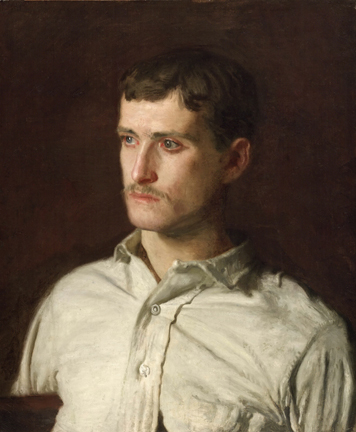

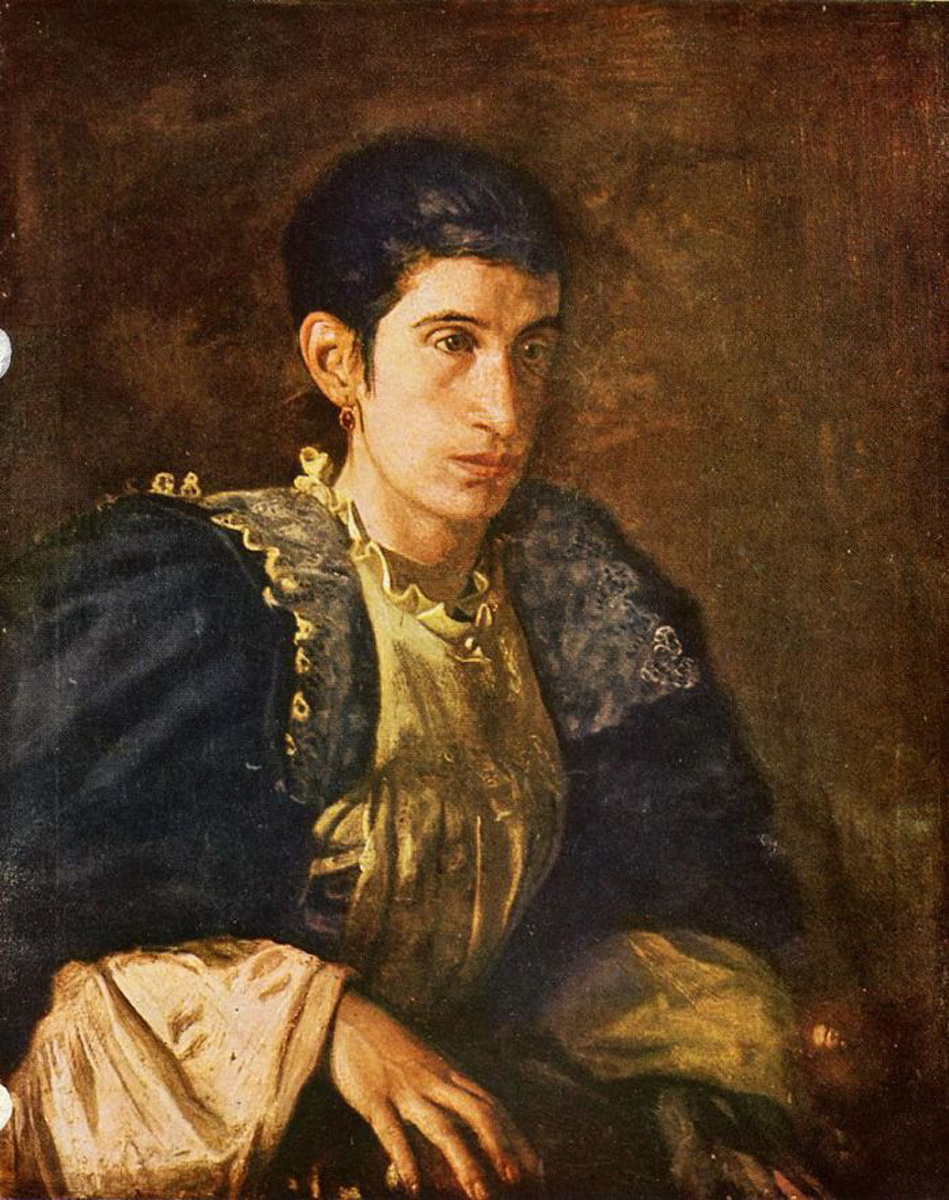

Home at last from years abroad that seemed long, Eakins couldn't get enough of his family. For a year or two he spent his time painting them. He painted his three sisters: Frances, with a scarlet ribbon about her neck and a scarlet sash over a white dress, Frances playing a grand piano; Frances playing the piano with her sister Margaret listening; Margaret seated at the piano and looking down at young Caroline, who is drawing on a slate on the floor. He painted his father bending over his writing. Then Eakins painted Margaret in the buff corduroy jacket and black hat that she wore skating, and painted a head and bust study of Margaret leaning back against a cushion in a chair, and did another head and bust sketch of Margaret. The only romantic paintings which Eakins ever attempted he did, about this time, of Hiawatha in a cornfield. A water color of standing corn with heads in the tassels was ruined by accident and destroyed. An oil on canvas was also of a field, but without corn, in which the dark figure of Hiawatha stands looking down at a shadow figure stretched out on the ground, the figure of Mondamin, friend of man, whom Hiawatha faint with fasting had fought, wrestling at sunset, and had overthrown. From Longfellow's Song of Hiawatha it was Hiawatha's Fasting that Eakins was depicting, the Indian legend of the coming of the corn. Hiawatha made a grave as he had been commanded, placed Mondamin in it with earth "soft and loose and light above it," kept it "clean from weeds and insects" and kept driving off the ravens until at last a "small green feather" shot up above the ground, announcing the arrival of that great gift, corn, for man. In the sunset sky are clouds shaped like animals – bear, buffalo, antelope, turkey. Then Eakins painted the Crowells, who were practically part of the Eakins family. His portrait of Katherine Crowell is sixty-two and a half inches by fifty, three times as large as the other portraits he had done so far and those he did immediately after that. She wears a white dress and is sitting in the high backed chair in which Eakins afterwards often posed his sitters. She holds an opened red fan in her right hand while with her left she plays with a brown kitten in her lap. Dr. Henry Ritter has noticed the arthritic fingers. It is a warm painting in mahogany red and golden brown and warm flesh colors. Whether Eakins painted it before or after he and Katherine became engaged nobody seems to know. He painted, too, Katherine' s younger sister Elizabeth with her school books and brown poodle; and he painted their mother, Mrs. James W. Crowell. It was their brother Will Crowell who had taken the walking trip in Europe with Eakins and who later married Eakins' oldest sister, Frances.

|

|

| |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then on June 4 of 1872 Thomas Eakins' mother died and abruptly Tom stopped painting the family.

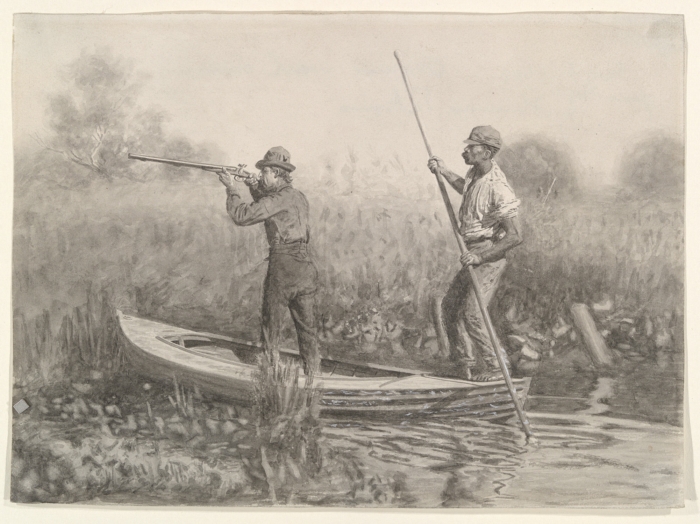

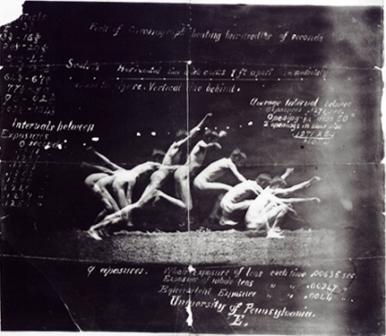

Going outdoors he became interested in the problems of perspective as presented by the difficulties of trying to paint a boat in motion. He tackled those problems so effectively that while he was still in his twenties he developed a valuable and original contribution to artist's perspective, which he later taught to his own students but which he would never give to anyone else to teach.

For Eakins, the mathematical sciences held a charm of security, a charm of dependability, which they have held for many before him and after. He saw more clearly than most that mathematics is the foundation of all beauty because mathematics is the science of proportion, and therefore even beauty can be somewhat stated in scientific terms. As for perspective, you must choose the point of view from which to depict the world as you see it, or you depict distortion.

Eakins was deeply interested in photography, and he was interested in the difference between a photograph and a painting. A photograph habitually distorts the thing in the foreground, partly because a camera has only one eye. Holiday-makers at the shore get themselves photographed on the sand with their feet stuck out before them just to have the fun of seeing themselves with enormous feet. A camera always distorts. There is a startling difference between a photograph and a painting by Monet of his lily pond and willows; there is a startling difference between a photograph and a painting by Thomas Eakins of a seated figure. It was an age in which artists were becoming interested in expressing with exactness the ways in which things appear to the human eye. In 1874, a few years after Eakins had returned from France and about the time that he was working out his method of perspective, the word Impressionists was coined to fit those artists who were trying to catch the instantaneous impression of variously reflected points of light. Eakins was more enchanted with the marvels of human anatomy than with reflections on a lily pond, more enchanted with the sweep of a boat in motion than with the iridescence of a cathedral seen through snow. But like the impressionists he was aware of an inner necessity to picture things as they truly seem to the two eyes of man. To Monet the solution was the skillful catching of reflections that changed with a moment of time; to Eakins the solution was found in a perspective that corrected the distortion of photography and reduced to a minimum the necessity of depending on estimated dimensions. To present the truth in a light that shows it without distortion is no mean achievement.

Eakins wanted a more exact way then the method of foreshortening based on rough estimates by the human eye to show the apparent change in the shape of things which occurs with a change in their distance from the beholder. The system of perspective used in mechanical drawing makes no provision for an unlimited number of changes in this distance. When you make a mechanical drawing, you choose the distance which will show the object without distortion, which will make the object appear as you know it to be from direct measurements. But when you paint a picture, you must take into account the distance from which you mean the picture to be seen, even though that is not the distance which would naturally show the objects without distortion. Eakins worked out his own one point perspective to solve this problem.

There are today books that point out as error the supposing that there is any truth in a painter's perspective; point out wrongly that there can't be and give as reason the fact that things are seen differently by an observer as he changes his distance from them. They recommend that the artist turn from perspective to use instead foreshortening, based on estimation of distances and of relative proportions. It was exactly this necessity of relying on estimates only that made Eakins work out his own method of one point perspective. Any perspective is relative, and Eakins chose to base his with mathematical exactness on the view that gave no distortion.

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

|

|

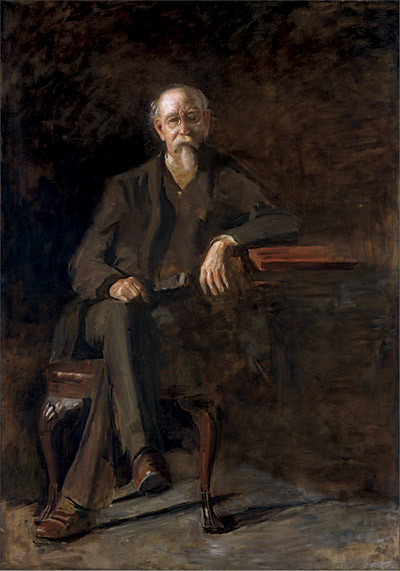

Although Eakins was very fond of sports, it was not so much a passion for boating which excited him to his series of boats on the river as it was this passion for perspective. He did perspective drawings for "The Pair-Oared Shell" in 1872 and from then on until 1876 he painted pictures which involved progressively more difficult perspective problems. The boats are turned at angles progressively more difficult to deal with. The problems are more fun when there are a lot of boats, sailboats, on the Delaware than when there are only a couple of boats on the Schuylkill, even though the sculls on the Schuylkill offer rowing oars and ultra-narrow seating spaces to be dealt with. Finally the canvas "Sailing" is the ultimate in handling the problems of perspective involved in boating. The sail-boat is travelling obliquely left away from us; it is so much in the foreground that we look down on practically its entire floor; the boat is riding up the side of a swell or wave; the wind is tilting the boat sharply over to the left and the two men in the stern (one has muscles taut with effort to control the situation) are leaning hard to the right to establish balance. Even the waves are in perspective. Eakins must have revelled in the various strains and slants and proportions presented for his mathematical mind to figure accurately. In time he brought the problems indoors by painting "The Chess Players" in which on a small bit of wood not quite twelve by seventeen inches he painted a crowded room. Two men are playing chess; chess board and chess men are in perspective. Eakins' father, Benjamin, stands watching them, his left hand on his hip, the right on the back of a chair, which is in perspective. To the left an elaborately carved table holds a glass decanter and a glass bottle and three glass wine goblets all of which are partly, colorfully, full, and all of which are in perspective. To the right the cat, which is in perspective, is busy washing itself. As far as painting in perspective goes Eakins had reached the limit. He made no further elaborations on that theme. Eventually he gave the "Chess Players" to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art which subsequently bought the perspective sketch made for the painting.

|

| "The Chess Players" |

| 1876 |

However, Eakins continued to use simply in his own paintings the method of perspective he himself had evolved. Even in his portraits, Eakins would put the chair in perspective and that would put the seated figure in perspective, too. As a teacher Eakins was very insistent that all of his students study this field and he gave them a course of twelve lectures with copious exercises from original notes which he always meant to publish but never did.

Henry Ritter, as a lad one of Eakins' students, ever afterwards claimed it was the thoroughness and precision of the perspective taught him by Eakins that made possible Ritter's later work in the drawing of crystals. Although Dr. Ritter was told on all sides verbally and in print that it was impossible to draw crystals as they appear in three dimensions, told that by people who thought they knew, he proceeded to do so. The drawings are very impressive shaded color studies of atomic or molecular groupings, determined by X-ray, in crystal structures; you see space solids developed upon a totally flat surface. By accurate mathematics Dr. Ritter allowed for the difference in the views of the thing as seen by the right eye and as seen by the left, so that the crystal drawings when put into a stereoscope give true pictures of the depth, width, height and general structure of the crystals. Several of the drawings give the effect of fourth dimensional perspective, for as you look at the color shaded molecular crystal structure, it seems to move out into space toward the beholder. The drawings themselves are delicate and beautiful, with various sized colored balls to mark the intersections of the lines of the lattice planes, and the sizes and positions of the atoms.

It was not alone in thoroughness and precision that Eakins' teaching was valuable. He made an original and telling contribution to the problem of perspective as the artist needs to use it.

The Perspective of Thomas Eakins

Eakins used as a control set of circumstances typical conditions that would show objects without distortion; for example, he let the object be 12 feet from the beholder and the eyes 60 inches from the floor. Acting this out, he would place a vertical stick 12 feet away from the spot on which the beholder was standing and on the stick would mark a point of sight, directly opposite the eyes, 60 inches from the floor. If these two dimensions gave an un-distorted view of the object, the dimensions to represent changes in its distance from the beholder could be worked out proportionally. For example, suppose the object is to be seen from a distance of 3 feet but without distortion. If you are 3 feet away, you are one fourth as far away as you were when the distance was 12 feet. Since you have divided the distance by 4, you must also divide the other dimension (the 60 inches to the point of sight) by 4 if you want to keep the same proportions you had in the first problem; 60 divided by 4 gives 15, and the point of sight is marked 15 inches from the floor on the vertical stick when it is 3 feet away. The problem is essentially one in ratios, 3:12::X:60, and X is seen to be 15.

In drawing after drawing Eakins used his one point perspective. He would draw with chalk a line on the floor of his studio and represent this on his paper by a vertical line down the center. Then he would place on the floor in their proper positions the things he was going to paint; for his "Chess Players", for example. It was the floor of the studio, squared off on his canvas, which Eakins put in perspective, parallel perspective, the lines that formed the sides of the squares fanning out to the base line at an angle determined by the height of the point of sight. The base line was made to cross at right angles the vertical line down the center at the point from which was measured the height of the point of sight. On this base line, a series of points was laid out at regular intervals, say an inch apart for example. Each of these lines was connected by a slanting line to the point of sight marked off on the vertical line that went down the center. The slanting lines represented the sides of the hypothetical squares on the floor. The distance to mark off the point of sight above the point at which the base line crossed the vertical was determined by the height of the eyes from the floor, or by that height as determined by Eakins' own method which has just been described. If we use the control problem we started with, the point of sight would be 60 inches above the point of intersection if the picture was to be seen 12 feet away; the point of sight would be 15 inches above the point of intersection if the picture was to be seen 3 feet away. The perspective drawing for one of these two sets of circumstances would look very different from the perspective drawing for the other set, because the slant lines representing the sides of the squares on the floor would fan out in one drawing at an angle very different from the angle at which they would fan out in the other. On his studio floor, Eakins measured for each object to be painted the distance from the chalk line. Then he blocked each object in on his perspective drawing a proportionate distance from the vertical line down the center. The vertical line on the floor was the guide for placing each of the objects in a relative position on the squares drawn in perspective.

An article of furniture that had irregular lines was always drawn first as though it were enclosed in a box; the box in proper position was first drawn in perspective and then the details of the object were put in afterwards. A mechanical drawing can be made only of things that are mechanical, not of living creatures such as moving animals and people. Eakins got around this difficulty in his portraits by putting in perspective the chair in which a person sat, using the chair as a frame of reference.

In his perspective drawings, Eakins got his horizontals in the manner usual for parallel perspective. He drew thru the point of sight a line at right angles to the vertical, and he measured off from the point of sight, to the right or left, on this horizontal the distance of the beholder from the point of sight. A diagonal was drawn from the point on the horizontal across the vertical to some point on the base line. At the intersection of this diagonal with each of the slant lines running from the point of sight to the base was drawn another horizontal. The series of horizontals gave in correct perspective the tops and bottoms of the squares. If the point on the first horizontal came inconveniently far from the point of sight, Eakins reduced the distance between the two points, but this gave a proportionate change in the distance represented between each two horizontals. For example, if he reduced the distance of the point on the horizontal from the point of sight by one fourth, then the distance between each of the other horizontals and the one next to it would be four squares instead of one. In making the drawings on paper, Eakins used three inks, red, blue, and black, to prevent confusing the many lines.

For the rest of his life Eakins taught his own pupils the theory of perspective as he had worked it out. Among the series of problems Eakins required of his students were problems dealing with objects that were tilted at some angle. A simple way to get the tilt was to draw a square divided by horizontals and verticals into smaller squares. If an object was tilted at an angle of 1 to 3, that could be represented by a line which passed diagonally through the height of three blocks. The diagonal would represent a line that could be drawn through the center of the object. The students were instructed to use a brick or a cigar box and place this in position with the necessary tilts. Eakins was particularly fond of the problem in perspective presented by a vessel sailing and would instruct his students to take into careful consideration the three tilts a sailing vessel was almost sure to have. She would probably not be sailing in the direct plane of the picture; she would be tilted by the wind; she would be riding a wave either up or down. The box or brick that stood for the vessel must be given all three of these tilts before the resulting drawing was placed in one point perspective.

Eakins was also fond of setting other problems that involved angles of tilting. The final and hardest problem his students had to do was to put in perspective a spiral stairway, but some of the other exercises could scarcely be called easy. For example, his students were required to do this particular problem of drawing a wheel in motion.

Hoop, Tilted

| Picture from eye 3 feet |

| Horizon 64 incites |

| Diameter of wheel 52 inches |

| Center 41 feet 1+ inches forward |

| To the right 6 inches |

| Tilt of wheel 1 to 3 |

| Running at an angle of 2 to 3 |

A mechanical drawing of a wheel 52 inches in diameter, tilted, seen from a distance of 3 feet gives an egg shaped distortion somewhat reminiscent of effects achieved by later artists in their experiments to depict exactly what they saw. Eakins worked out the problem by first drawing the wheel, tilted at two different slants, on a ground plan marked off in squares. This drawing, placed in Eakins' one point perspective, resulted in a wheel that was seen without distortion from a distance of three feet. The squares of the ground plan were the things put in perspective and used as guides for sketching in the tilted wheel, the lines of the wheel being made to touch the squares on the perspective drawing at points corresponding to those at which the lines of the wheel touched the squares on the ground plan. Inaccuracy in placing the points could be reduced to a minimum by subdividing the squares until they were so small that a possible error could be made to be less than any given amount.

Here again Eakins was master in his use of the problem. The oval plaque, "Knitting," shows a middle-aged woman in old fashioned dress seated beside a table with a tipped top. Modeled in high relief, the edge of the round table shown thus in a vertical plane is seen as an oval extending out from the plaque into space. The table slants away from the plaque at a sharp angle, giving Eakins his chance to use complicated perspective. For a companion piece, "Spinning," an oval in high relief, a young girl in short waisted dress sits on a stool at a spinning wheel. Both plaques were modeled about six years after Eakins had done the "Chess Players" in perspective, were modeled while Eakins was at the Academy of the Fine Arts as teacher in the 1880's.

|

|

End of Eakins' Perspective

* * * * * * *

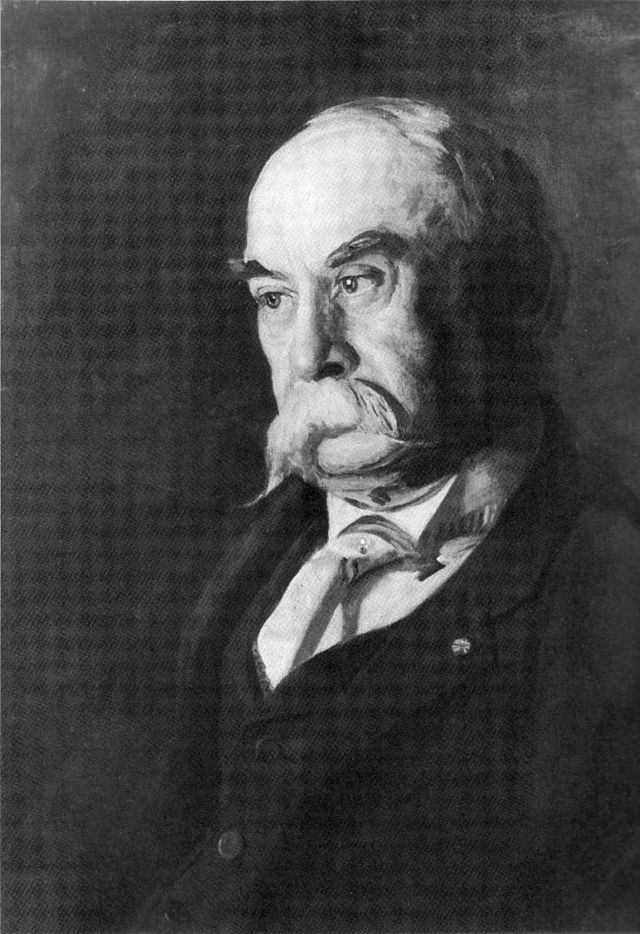

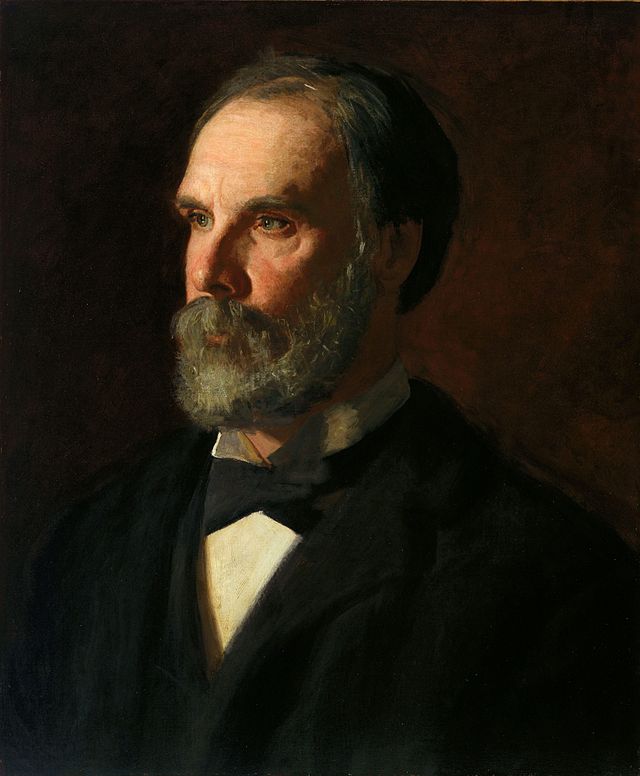

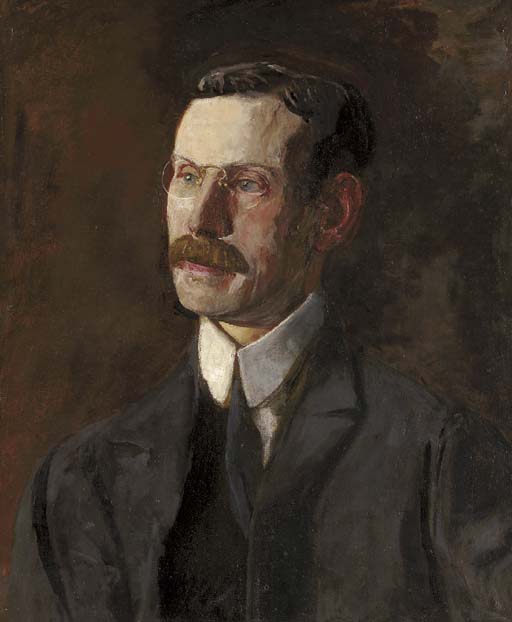

When Eakins was thirty, in 1874, he was writing to Kathryn Crowell, his fiancée, rather gentle, formal little letters. One of Kathryn's best friends was Sallie Shaw and another was Thomas Eakins' sister Maggie, all three about the same age. Over seventy years later Sallie Shaw remembered Kathryn well, remembered her as very short, with medium brown hair, "just a good decent girl" and not a tom-boy like Sallie herself. Kathryn played the piano but "nothing special;" she was not artistic. Although she enjoyed fun, she herself did not make much fun. Sallie thought Katie Crowell was rather exclusive, not associating with many. As Sallie Shaw remembered it Thomas Eakins associated with a great many, with so many girls in fact that his father, Benjamin Eakins, put his foot down and told Tom he had to get engaged. It was his father who had really engineered Tom's engagement to Kathryn Crowell. The father, Benjamin Eakins, was Sallie Shaw's great uncle, and she thought him a wonderful looking man who held himself with great dignity. His hopes for his son Tom's marriage were abruptly ended. Kathryn Crowell, in 1879 when she was twenty-seven, died of meningitis; the dates of her birth and death were recorded in the Crowell family Bible.

As Sallie Shaw saw matters, his family thought that Thomas Eakins was very domineering. His older sister Fanny gave as her reason for not having gone to high school the fact that Tom didn't approve of higher education for women. Sallie Shaw herself was very proud of having gone to the Girls' High School, then near Tenth Street between Vine and Race. Fanny, however, had been well trained in languages and music, and the two younger sisters, Margaret and Caddy Eakins, went to the high school. Sallie Shaw thought Tom Eakins ruled his mother as well as the rest of the family. Tom Eakins was always teasing Sallie Shaw about her going to church and to Sunday School. It got to be very annoying. Once when he did that at the dinner table, his father lit into Tom and lectured him so that he never did that again.

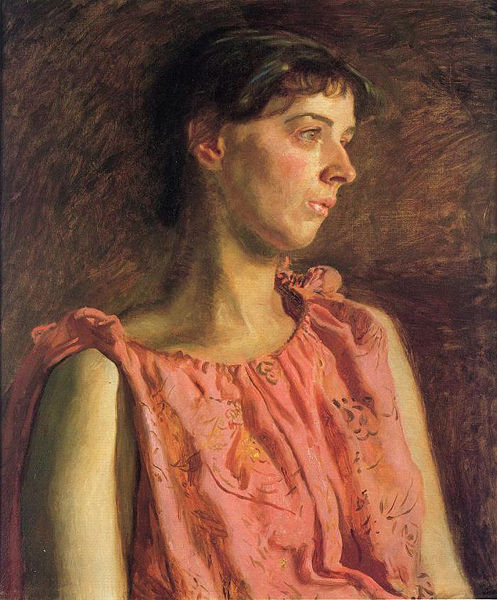

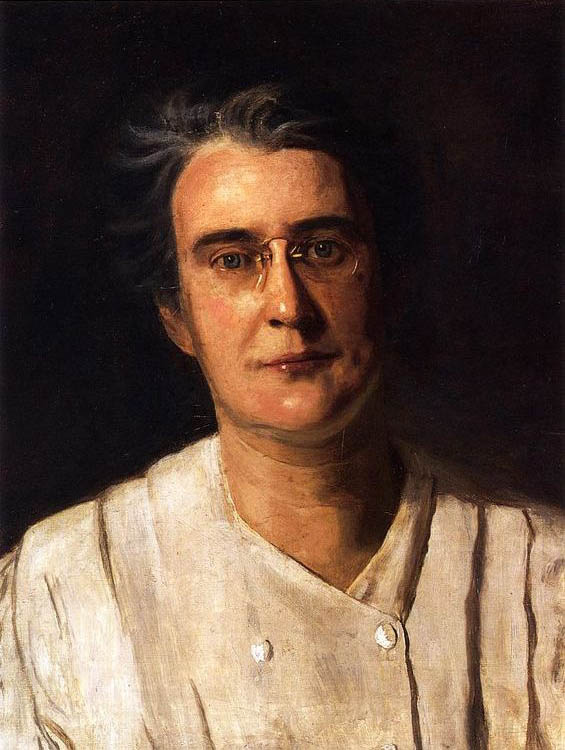

Thomas Eakins painted a portrait of his mother, but he painted it about two years after her death, about 1874, from a photograph. Her brown hair, parted in the middle, is drawn down smoothly into a knot, and a narrow white collar edges the throat of her black dress. The next year, in 1875, Eakins painted Katie Crowell's sister Lizzie, "Elizabeth at the Piano". She was younger than Kathryn and very vivacious as well as pretty. Rumor had it that she was the one Eakins loved but never won.

|

|

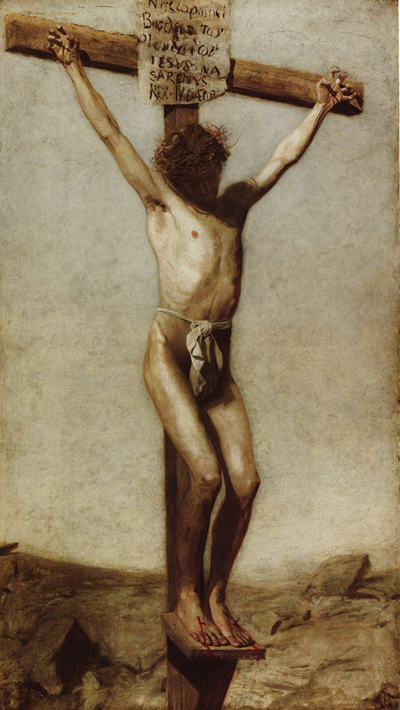

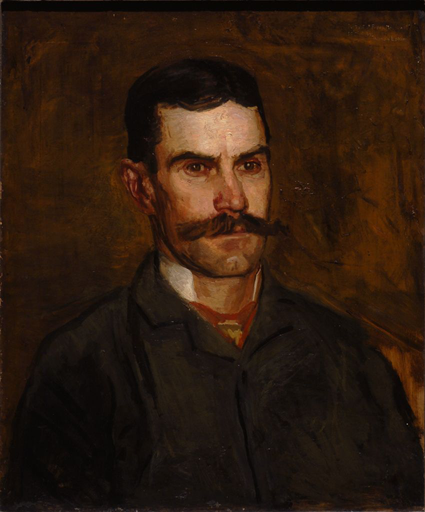

In 1873 and 1874, Eakins went to the Jefferson Medical School to study anatomy, a subject which became for him the love of a lifetime. For Thomas Eakins,real romance lay in this, the study of anatomy. Once he had found it absorbing, to Eakins no one was a bore, for every one had muscles and no two people were built alike. One of the astonishing things about the study of muscles is the extent to which they vary. Take the sartorius muscle which flexes the leg upon the thigh. Its variations included slips of origin and the ability to split up with a large selection of choices for insertion. Or it may just be absent. There is a surprising amount of absenteeism among muscles. The bodies most often available for dissection purposes are those that are to be buried at public expense and are therefore those most likely to have poorly developed muscles with many missing completely. Once after Eakins had been dissecting for years, a huge and muscular stevedore was killed by some accident. This was a bonanza. The man had been killed in some way by which he was not mutilated. Eakins and his students, able to obtain the body, gleefully made casts of section after section in the dissection room at the Academy of the Fine Arts. The casts were nicely colored in different shades of red and kept for years as models for the other students to work by. Those casts were among the many things that had belonged to Eakins which, after his death, were treasured by his wife, who had them cast in bronze. Throughout his life Eakins insisted his students should study anatomy, for to cite a book on the subject already in existence when Eakins went to Jefferson, the famous "Gray's Anatomy," it is impossible for a person to throw just one muscle into action; it is movements, not muscles, that are represented.

Eakins shared the admiration for the human body which Oliver Wendell Holmes expressed in the "Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table" by "The Living Temple or the Anatomist's Hymn." Eakins realized with Holmes that "we find a mathematical rule at the bottom of many of the bodily movements," and that the pelvis is the center of the body around which all the rest is built. Wrote Holmes the Autocrat: "You think you know all about walking, – don't you, now? Well how do you suppose your lower limbs are held to your body? They are sucked up by two cupping vessels, ('cotyloid' – cup-like – cavities,) and held there as long as you live, and longer. At any rate, you think you move them backward and forward at such a rate as your will determines, don't you? On the contrary, they swing just as any other pendulums swing, at a fixed rate, determined by their length. You can alter this by muscular power, as you can take hold of the pendulum of a clock and make it move faster or slower; but your ordinary gait is timed by the same mechanism as the movements of the solar system."

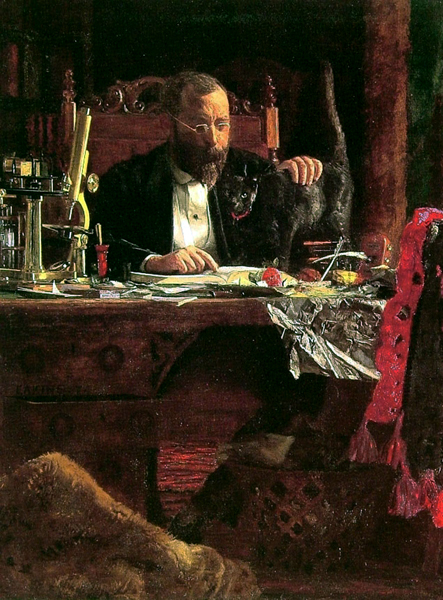

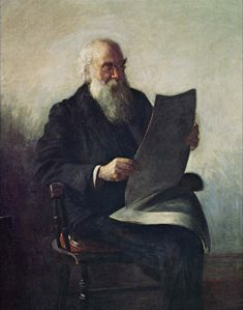

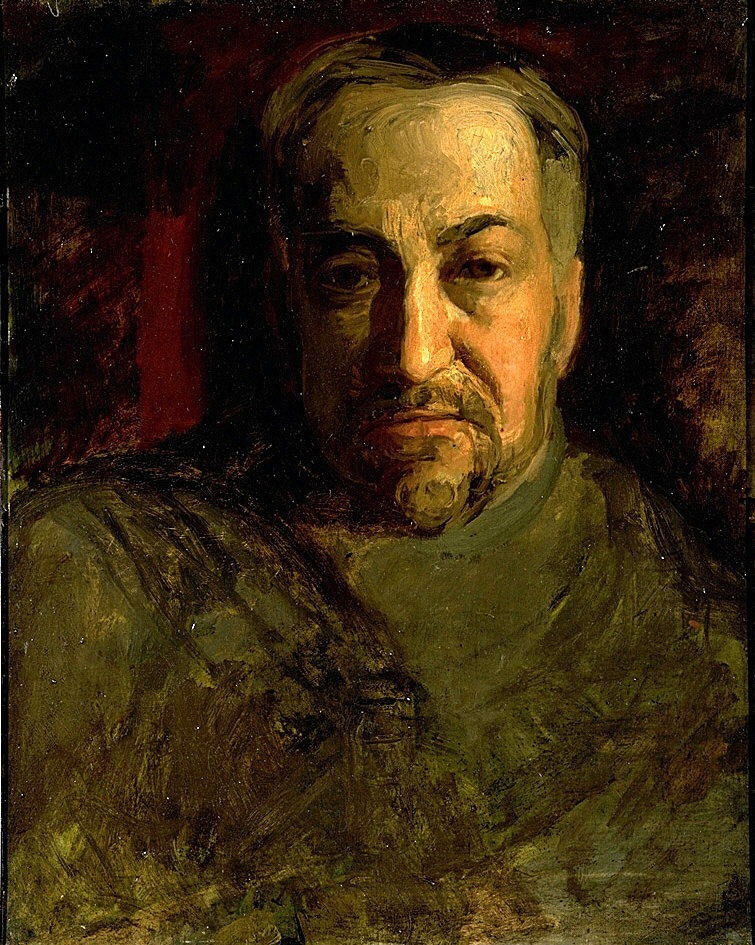

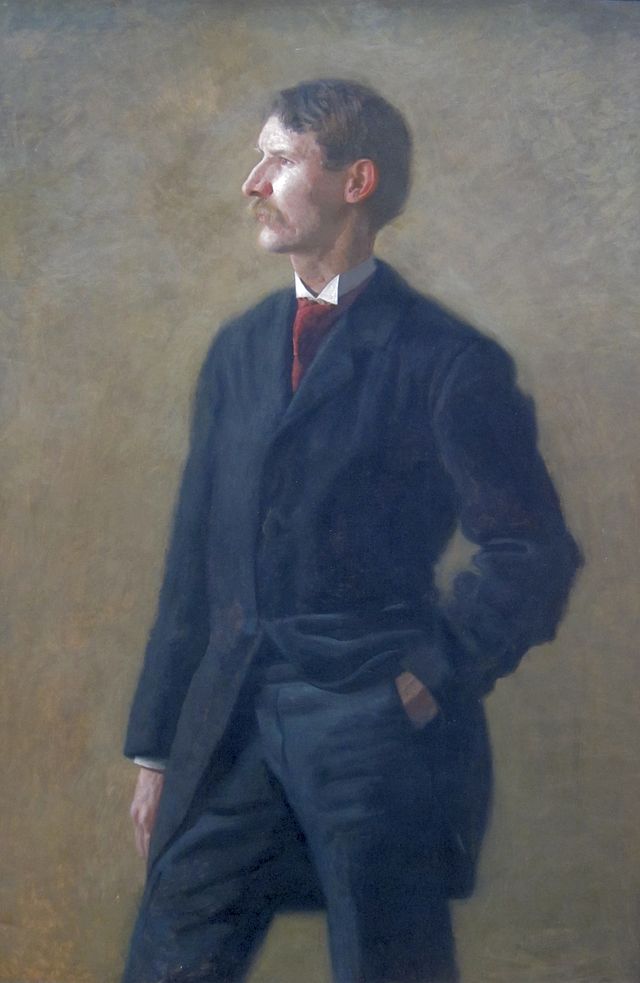

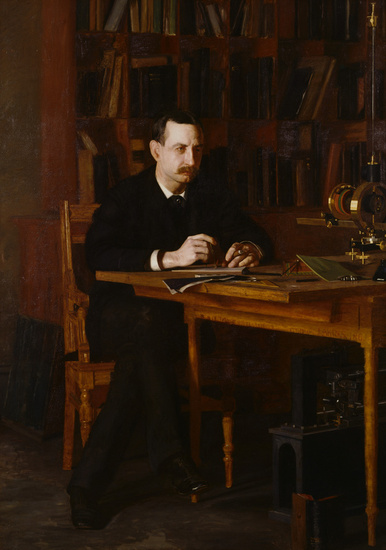

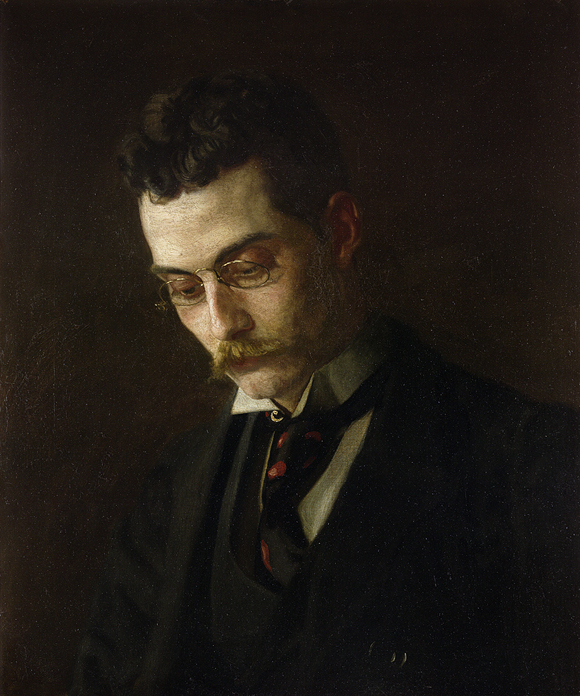

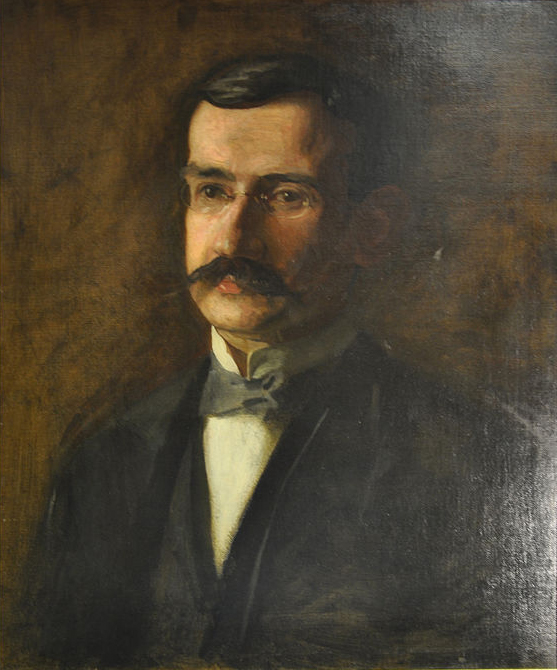

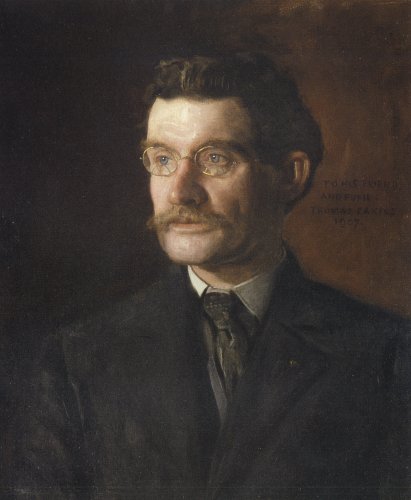

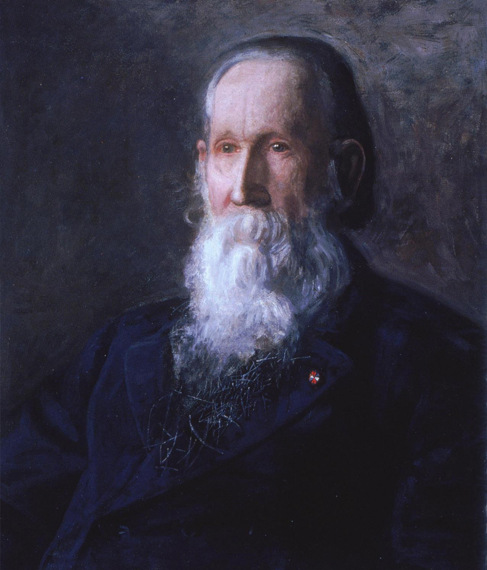

Eakins himself once wrote that he had "taught in life classes and lectured on anatomy continuously since 1873." However, this could not have been at Jefferson for he would have needed a degree in medicine to have taught there. He never registered in the Medical School but simply sat in on the lectures. In 1874 Eakins did a portrait of one of the Jefferson professors, Benjamin Howard Rand, professor of chemistry and for some years dean of the College. Professor Rand had taught at Central High School when Eakins was there as a student. Later Dr. Rand was for years secretary of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences before which eventually Eakins presented his original findings on those muscles that passed two or more joints. It was in this paper on muscles that Thomas Eakins finally articulated his philosophy of painting. It was much earlier when he was only thirty that Eakins asked Professor Rand to pose for a portrait.

In this first portrait of a man of science, Eakins painted Professor Benjamin H. Rand seated behind a table rather over-full of a surprising collection of things. On the left stand a microscope, test tubes and other instruments, setting a precedent Eakins followed the rest of his life of including in a portrait something to suggest the achievements of the person posing. The liquid in one test tube is a brilliant red, and the brass of the microscope shines. On the right of the table is a black cat which Professor Rand holds by the back with his left hand while with his right he points to a page of an open book. A spot of color is achieved by a pink rose, green leaves, lying on the book, a piece of bluish crinkled paper hanging down from the table over a blue cover, and a vivid piece of reddish purple cloth with tassels over a chair in front of it. These props from the artist's studio thrust onto a man of science created an effect which Eakins never strived for again. They are conspicuously absent from his other portraits.

|

|

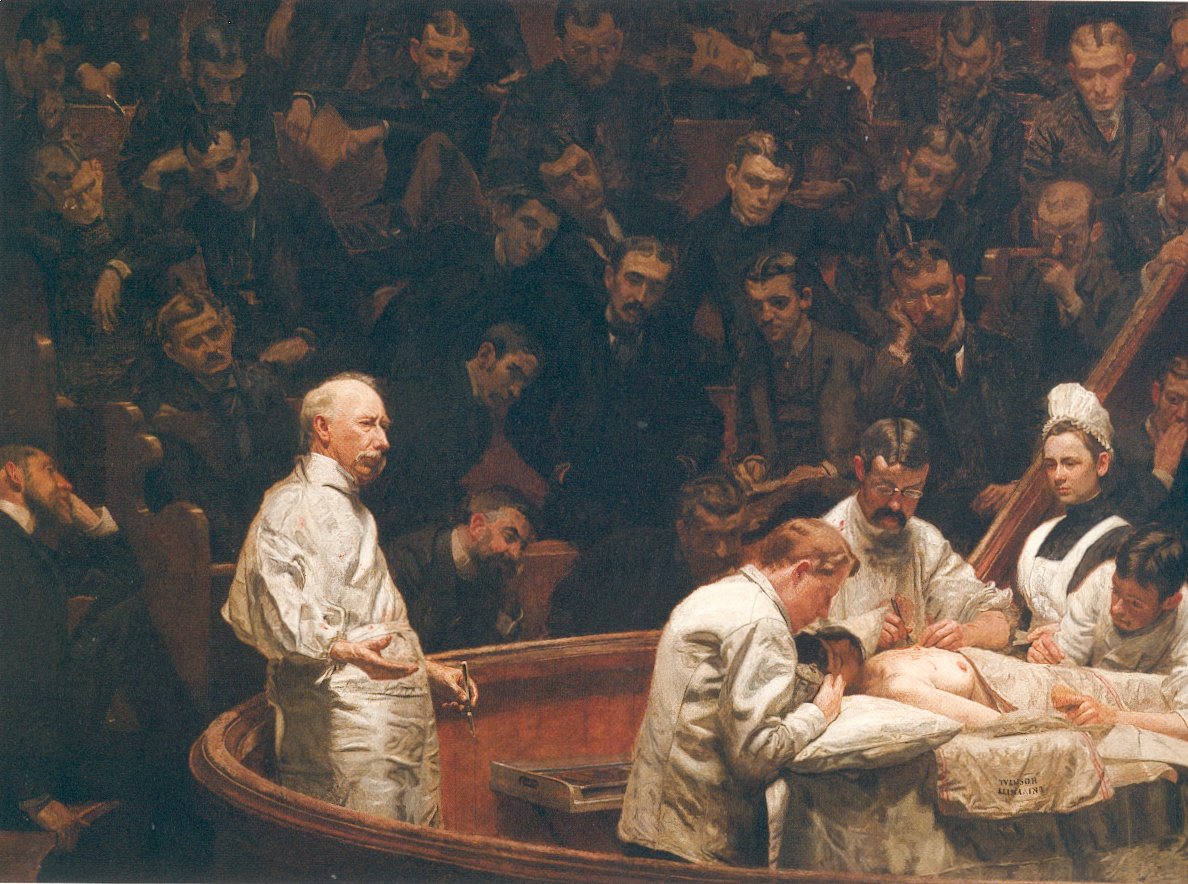

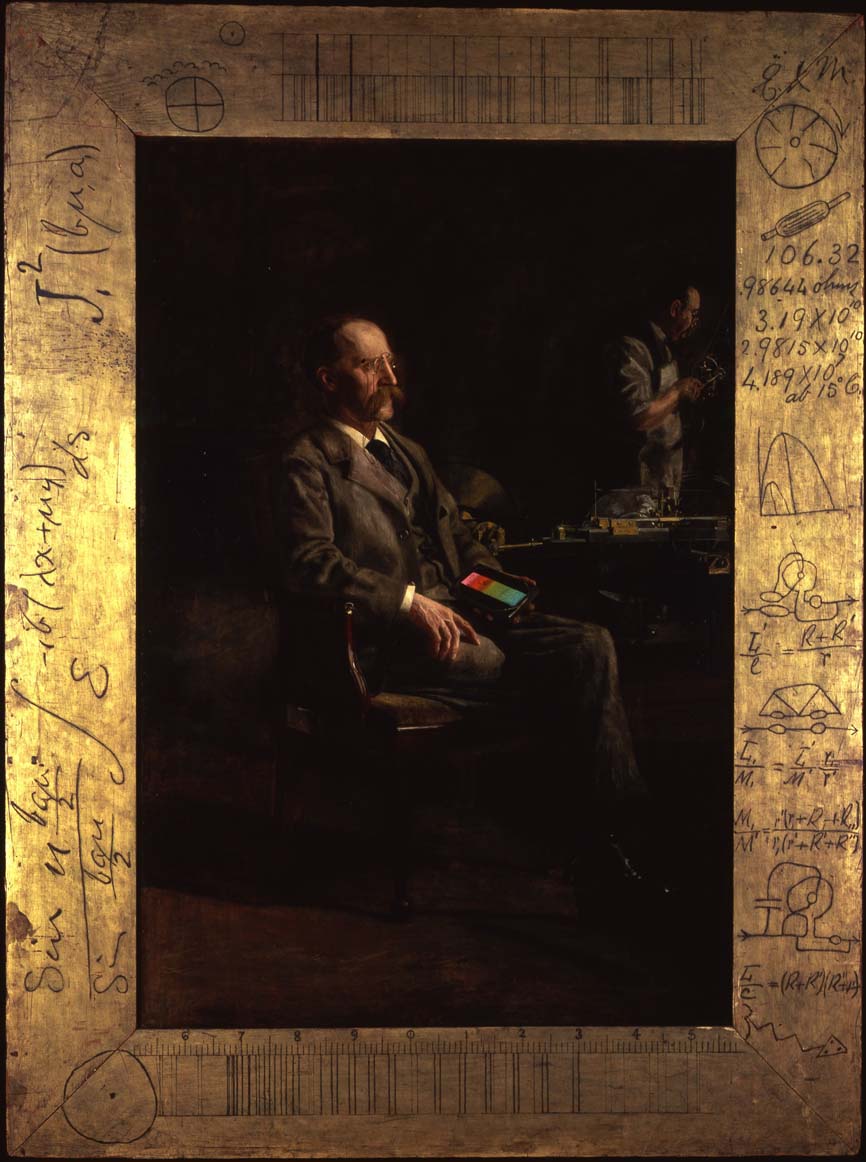

In 1875 Eakins painted the "Gross Clinic," and in 1876 the portrait of Dr. John H. Brinton, also of Jefferson, the surgeon who succeeded to the chair of Dr. Samuel D. Gross. The "Gross Clinic" was destined to become one of the most famous of the paintings by Thomas Eakins. It is, as its name suggests, more than a single portrait. In the foreground Dr. Gross, scalpel in hand, explaining, stands to the left of an operating table around which are grouped four assisting physicians. At the far end of the table the patient's head is covered with a towel, and in the foreground the upper part of the left leg is exposed for the operation. Dr. James M. Barton is probing the wound and behind him, leaning against the wall, is Professor Gross's son, also a doctor. Each figure in the painting is a portrait. In the matter of color the painting is somber, relieved by the high lighted woodwork across the front of the tier of students attending the clinic, three of whom are asleep, and by the warm flesh tints of the portraits. The instruments in the tray in the lower left-hand corner are also high lighted and placed on a towel with a lavender-reddish border and yellowish white fringe. A blue towel folded is under the patient. Blood red is so tellingly used on Dr. Gross's fingers, the patient's wound, and the linen, that it caused considerable agitated comment.

|

| "The Gross Clinic" |

| 1875 |

With penetration Eakins painted Gross as capable of being completely oblivious to the horror agonizingly endured by the woman seated at his elbow, the patient's mother. In speaking of his many fruitful experiments in vivisection, Professor Gross had written that they had "involved a great sacrifice of feeling on my part." He had become a doctor in days when heroism was the quality most needed for the task. Anaesthetics came into use only during Professor Gross's own lifetime, and his early practise belonged to the time when it was a feat of endurance and bravery just to reach a patient's bedside at night over impossible roads. Dr. Samuel D. Gross had himself gone to New York City and faced the cholera epidemic of 1832 when it was at its height in midsummer. The violent contortions of bodies after death struck him as primarily odd, with "legs thrown about in different directions, literally kicking the air and everything else coming within their reach." He found the medical treatment of his own day very unsatisfactory, remarking in his autobiography, "I, however, soon carved my own way." This he did in part by writing his own elaborate "System of Surgery."

There is no greater contrast than that between Dr. Samuel D. Gross of the "Gross Clinic" and Dr. D. Hayes Agnew of the equally famous "Agnew Clinic" painted by Eakins some years later. Dr. Agnew, a very gentle person who observed the Sabbath Day religiously, had been impelled to become a great doctor by his conviction that in healing men he was serving God Himself the Lord. Not only the sick whom he healed but also the many doctors who consulted him remembered Dr. Agnew for his marvellous kindness. Also he had come to his profession when it was somewhat less grim than it had been shortly before. Dr. Samuel D. Gross had been driven by a relentless ambition which succeeded directly a boyhood made miserable by blushing shyness and timidity. Dr. Gross had deliberately and grimly set out to be a great doctor, and had succeeded. Whereas Dr. Agnew was mellow, Dr. Gross, much the older of the two, was smart. The latter became a Unitarian because "many of the most distinguished men that ever lived were Unitarians, or upheld Unitarian doctrines," and he regretted that he was so busy professionally on the Sabbath that he could attend but few services. But Dr. Agnew and Dr. Gross were alike in this: however different the motives which urged them on unceasingly, both were in truth great physicians. Eakins showed by his expert characterizations that he knew them well.

|

| "The Agnew Clinic" |

| 1889 |

Some years later Eakins painted two other professors of the Jefferson Medical School, Professor James W. Holland with his marvellously characteristic and expressive stance, a painting titled "The Dean's Roll Call"; and Professor William Smith Forbes, his hand on "The Anatomy Act" which he drew up for Pennsylvania.

|

|

It was at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 that the "Gross Clinic" was exhibited. Eakins, to his disgust, was unable to get it hung in the section devoted to art because of his choice of subject. The painting was placed instead in the room for the display of medical supplies. There it hung on the west wall and dominated the place.

Although the two "Clinics" were painted in Eakins' studio, his anatomical drawings were made in the dissecting room. Some elaborate human anatomical drawings made by Eakins are dated 1878.

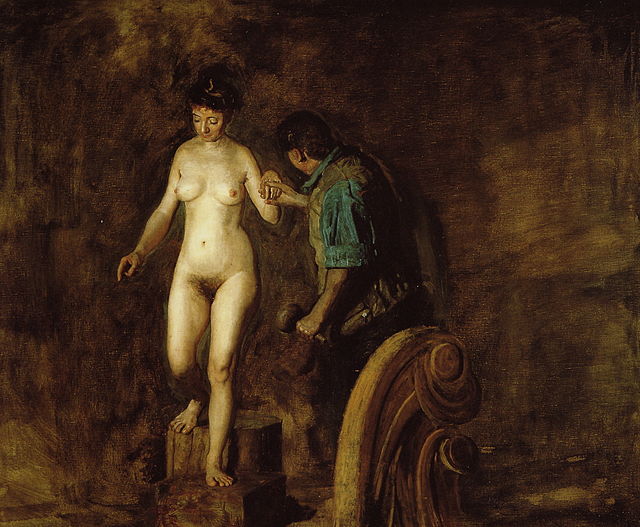

The year that Eakins was forced to place the "Gross Clinic" in the medical section at the Centennial Exhibition, he designed a study of Columbus very sad in prison. The white haired explorer sits on a prison bench and head in hand wearily meditates upon a globe. But the study was never completed. The next year Eakins produced instead some of his most decorative work; a painting of William Rush carving an allegorical figure of the Schuylkill River, and several charming little water colors.

|

The painting of Rush carving is primarily a study of a nude figure as she poses on a block of wood; she turns slightly to the left with her back to the beholder, and she balances with her right hand "Webster's Unabridged Dictionary." Her colorful clothes are on a chair in the foreground and at the right sits the chaperone knitting. In the left background the first native-born American sculptor, William Rush, dressed in the breeches and waistcoat of 1809, is carving out of wood his statue, "Water Nymph and Bittern", which was for the new Center Square Water Works on the spot which is now City Hall Plaza in Philadelphia. His water nymph is clad in classic draperies and she has a classical hair-do. The bittern on the right shoulder is an American bird familiar to the marshes that bordered the Schuylkill in Philadelphia where later grew up Boat House Row. The up-raised neck and beak of the bird form the fountain. Thomas Eakins himself wrote of Rush's statue: "A withe of willow encircles her head, and willow binds her waist, and the wavelets of the wind-sheltered stream are shown in the delicate thin drapery, much after the manner of the French artists of that day whose influence was powerful in America." In the painting by Eakins a rich background suggests the achievements of the sculptor Rush, the scrolls and designs for the figure-heads of ships, ships that went to London and drew crowds to see his work. In the painting the figure of Washington, whom William Rush knew as a personal friend and served during the Revolution, represents Rush's statue of him long in Independence Hall. Its place on the rostrum of the Senate Chamber where Washington was inaugurated, on the second floor of Congress Hall, is appropriate. It is appropriate, too, that in time Horace T. Carpenter, who had been a pupil of Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, became curator of the five buildings which make up Independence Hall, having as his office the John Adams Room directly next to the Senate Chamber with its statue by Rush. To add one more link with Eakins, the latter's maternal grandmother, Margaret Jones, had as a child been picked up and kissed by Washington on his triumphal entry into Trenton.