THE RUNAWAY PAPOOSE

CHAPTER I

A NIGHT OF ADVENTURE

Little hares go frisking by,

Racing cloudlets in the sky!

All the desert seems to cry–

"Hi!–Children–Hi!

Here's adventure–here is fun,

And a strange new trail to run,

Leading to the setting sun

And lands that meet the sky!"

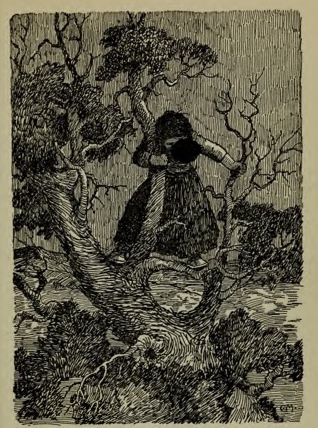

UP OVER the edge of the desert

peeped the big yellow moon, and Nah-tee shivered and drew her little dress

close about her shoulders. Nah-tee

was sitting high in a pinyon tree, as

high as she could go, with her little

feet drawn up under her and her heart going "Boom–boom–boom" like a tiny drum in her breast,

keeping time to her thoughts. For Nah-tee was

frightened–never in all the few years of her life had

she been so frightened–and she trembled so, all

over, that even the pinyon tree trembled, too, and made

its little cones to shake in time to the beating of her

heart. And she had very good reason to be frightened–even a big one would have trembled, too, and

Nah-tee was very, very small.

UP OVER the edge of the desert

peeped the big yellow moon, and Nah-tee shivered and drew her little dress

close about her shoulders. Nah-tee

was sitting high in a pinyon tree, as

high as she could go, with her little

feet drawn up under her and her heart going "Boom–boom–boom" like a tiny drum in her breast,

keeping time to her thoughts. For Nah-tee was

frightened–never in all the few years of her life had

she been so frightened–and she trembled so, all

over, that even the pinyon tree trembled, too, and made

its little cones to shake in time to the beating of her

heart. And she had very good reason to be frightened–even a big one would have trembled, too, and

Nah-tee was very, very small.

She had no eyes at all for the beautiful desert that lay like a great bowl of silver in the moonlight below and around her, or for the powdery gray sage–or the strange-shaped rocks with the black shadow pools under them. Nah-tee was Indian, and all the things of the desert she knew and loved well, but it was a daytime desert that she knew, and never before had she been alone at night in this great strange world. But it was not the night she was afraid of, or the hoot owl that called from a mesquite tree, or the shadows that crept from bush to bush–no, each one of these things alone would have made her to laugh at the thought of fear–it was not a thing that she could see or hear that made the trembly feeling to come, it was something she could not see or hear–not now.

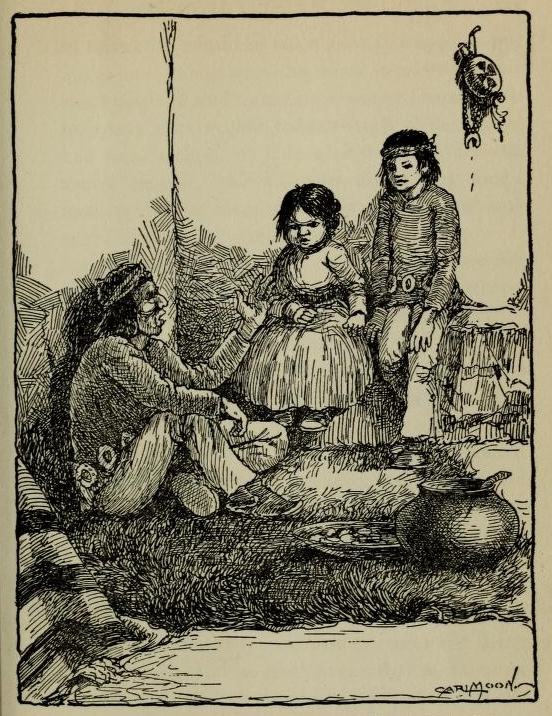

Only this morning–but now it seemed a great, great while ago–only this very morning she had been safe with her father and mother in the shelter place they had built in the desert–with all the friends and loved ones close about them–and last night when the darkness had come the big camp fire of mesquite boughs had sent up snapping bright flames and driven the night dark far back into the desert, where it belonged, and the warm shadows had danced up and down on the tree bark of their shelter home and the big supper pot had bubbled and boiled and sent forth odors so delicious that the very memory of them made Nah-tee weak and squirmy with hunger.

And now, to think of it, it seemed a very strange thing that all of her people had left the shelter of their far-away, cosy pueblo, with the little fields about them, to come out into the desert as they had done. Why had they done that? And the wonder of it made Nah-tee to open her eyes very wide even in the middle of her fear thoughts. For many days they had traveled over this desert, stopping at times and building little shelters of pinyon and mesquite boughs that they might rest awhile and hunt for food to eat–and then they would go on again. It had been very comfortable in that far-away home place near to the hills where little streams ran in the season of rains, and there were deer and plenty of small animals, and many birds, and trees with yellow peaches hanging on them, and the winds made queer noises as they came singing down the cañons. But it was nice in the desert, too–there were rabbit hunts and exciting games that could be played in the sandy washes–and strange people riding by, and always that big wonder of where they could be going–yes, in the desert it had been nice, too–until this day–and a little fresh shiver came to Nah-tee at the thought–this day it had not been nice–this day had been a very terrible day, and not yet was the bad part past.

This morning her father had talked with happy words and had said that now they were not far from the end of their journey and that a new home place was very near, and there were smiling looks on all the faces, and they got ready the packs on the horses and burros to begin again the travel that they knew so well–and then–men had come, riding fast over the desert–men they had never seen before, who began to talk in loud voices and then to fight!

Very quickly there was great confusion in the little camp. The women ran with frightened cries to the shelter of the twig houses they had not taken down, and Nah-tee ran, too, only there was a strange man who stood between her and the shelter houses, so she could not run that way, but ran to a little wash that was near and slid down the steep, sandy bank and ran on–and on–and on–and not until she was altogether out of breath did she stop–and when she stopped she hid in a big clump of sagebrush and listened–and listened! It seemed as though the very world had turned upside down, and for a little even the thoughts in her head stood still and waited for what would happen next. What had happened? Nah-tee did not know. Why would anyone want to fight her father, who was kind always and never said angry words, and the others of her people who had harmed no one? And what would happen now? She listened as carefully as she possibly could, but there was no sound from anywhere, except just the quiet sounds that people do not make–the wind in the dry leaves, and the whisper of small life under the sage. But Nah-tee did not come out from her hiding place in the sagebrush, not for a long, long time; she stood and waited and listened and wondered what she should do–that was the big thought in her mind now–what should she do? If she waited and waited a very great while, surely those men would be gone and she could creep back to the home place to the warm comfort of her mother's arms and the cheery blaze of the camp fire. She must have come very far from the camp–she could not guess how far. She crept out now from her bush and looked down the wash–she did not know that the little wash, which had been made by many seasons of rain, branched away in many different directions. She had not noticed that as she ran–she had not noticed anything at all–but as she began to go back cautiously, when the shadows of evening lay long and purple across the desert, then she noticed that there were many little washes all running into one and then running out again in a most confusing way. And when she followed one wash for a very long way she found it was not the right one; and another one did not lead back to the camp; and another one was strangest of all; and it was then that the trembly feeling began to come, for Nah-tee was lost, and now she did not know which way to go at all.

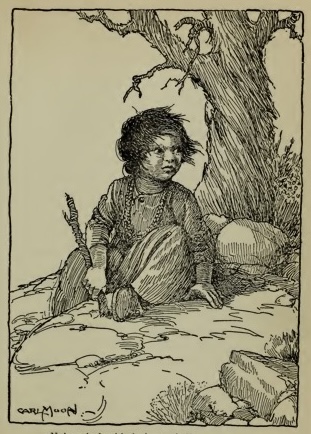

Nah-tee was very small, and her dress was long, and in the dim light she looked like a queer little woman, for her mother dressed her just as she was dressed–in a brown velvet waist with silver buttons and a dark, full skirt that came almost to the ground. Her hair was brushed back, black and glossy, from her face, and was tied in a little bobby knot at the back of her neck, and there were bright bits of blue turquoise in her ears, and silver beads about her neck and silver bracelets on her little wrists, and on her feet she wore the brown buckskin shoes of the Navajos, a little higher than moccasins and fastened with a silver button; but the fading light did not show that her cheeks were like little apples browned by the sun, and her big black eyes had laugh twinkles in them when the fear thoughts were not there. But now they did not have laugh twinkles, and Nah-tee did not feel like a woman at all, even a very small one–she felt like the littlest thing in all the world, and very alone and very hungry, for all day she had had nothing to eat except a few pinyon nuts that she had found on the ground.

But the really trembly time came with the dark, before the moon came up. The whole world seemed to change with that dark–the daytime noises stopped and strange night ones began. The coyotes barked–more coyotes than Nah-tee had ever heard before–and there were strange, prowly noises in the sage, and things that crept with scratchy sounds over the rocks. Anyone would grow trembly with sounds like that, and after a short while of listening Nah-tee ran like a little squirrel for the most branchy tree she could find and scrambled up into it and drew her feet up and sat and trembled–and listened! But she did not cry, somehow she did think about that, and after a time she did not tremble so much, and let down her feet just a little way. The noises did not come any nearer, and not yet had anything hurt her. And now she must think what to do. Thinking was a thing Nah-tee had never been told how to do. When her mother had taught her to do things they had always been things for her hands to do, and her mother had shown her how, and she had done them very carefully and well; and for the rest of the time she ran in the sunshine with the other children and hunted in the little cañons for arrowheads in the rocks, and found queer bits of stone and flowers in the desert, and ate berries and nuts when she came across them, and learned the ways of the animals she knew, and listened to the song of the wind in the trees, and all that did not take thinking at all; but now was a time when she must think!

"Au–ouooow!" said the big empty place inside of Nah-tee where supper had always been on other nights. "Au–ouoow, how I am hungry!" And "Whoo–o-ooo!" cried the little hoot owl in the mesquite tree, and "Yow-wow-wowooo!" cried the coyotes off in the desert, and how could any little girl think with all that noise around her? But just as she thought that, a new sound came through the night, and Nah-tee gave a little jump in her tree place, and her heart began to beat even faster than before. It was a very different noise than the others that she had been hearing, and at first she did not know whether to tremble more or to stop trembling altogether, for it was a voice that she heard, and the voice spoke words in Navajo–words that she understood very well, for Navajo was much like the language spoken by her own home people. It was such a strange thing that a voice should speak in this lonely night place that almost Nah-tee could not believe that her ears had told her a true thing, and she did not breathe for a little to listen for the voice to come again. But it did not come. Far away had sounded that voice, but very clear on the air, and the words brought a smile feeling to the lips of Nah-tee; and fear thoughts cannot stay very long when smile feelings come.

"Ai-ee, but the world is big when the moon shines down," had said that voice, "and if you could talk to me, Chingo, it would not be so lonely in the night"; and the sharp bark of a dog had answered to the voice, and Nah-tee knew, just as well as if she could see them with her eyes, that a Navajo boy and his dog were watching sheep in the desert. It was strange that she had not heard the sheep, for always you can hear sheep in the desert, but she knew that they were there even though she stretched her neck and looked and looked and could see nothing at all but the moonlight on mesquite, sage, and cactus, and the black shadows that lay still when she looked straight at them but seemed to move if she turned away her head. And then, quietly, like a little mouse, Nah-tee began to move in her tree and to slip her feet down a little farther and a little farther, hugging tight to the rough bark until she was standing on the ground again with her heart beating so fast she could not have heard even a loud noise if it had come. She was going to find out where that voice came from–and very quickly. She must find out, for she could not stay any longer in this strange, big place all alone and with the hungry feeling inside growing bigger and bigger every minute. She stood uncertainly by the tree for a moment and tried very hard to hear a sound that would tell her in which direction to go; but, except for those far-away coyotes, everything was very

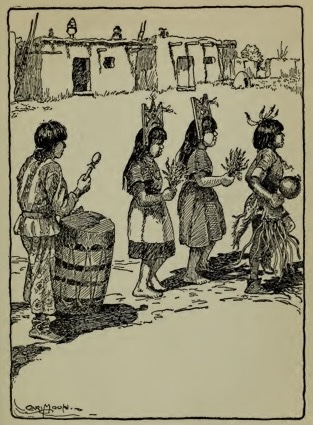

Quietly, like a little mouse, Nah-tee began to move in her tree.

still–and then–Nah-tee turned her head suddenly, and her little nose went up into the air and sniffed–hard! It was a food smell–a very delicious food smell–and almost without her knowing it her feet began to lead her in the direction from which it came.

Her soft little shoes made no sound at all on the hard ground, and so there was not even the bark of a dog to tell of her coming. Large rocks were in this place and in the direction in which she was walking the ground sloped very sharply down after a little rise, and that was why, even from her tree, she could not see very far. And now she could hear the sheep, too, making soft little bleatings as they tried to find comfortable places for the night–and suddenly she saw a little fire behind a big rock, and she stopped when she realized how very close she was now to the boy. She could see that it was a boy and his dog, as she had thought; and there was a pot, too, steaming over the fire. It was the little trail of good smell from that pot that had brought Nah-tee very surely to this place. The dog turned suddenly toward her now and gave a low growl with all his hair sticking up, and the boy looked up, too, and saw the little form so close to them in the rocks, and his eyes opened very wide with surprise, and he called quickly to the dog:

"Down, Chingo–can you not see?–this is not a wolf. Are you a real one?" he called to Nah-tee, "or a shadow thing of the night?"

Nah-tee drew a very deep breath.

"Oh, how that smell is good!" she said, and the boy threw back his head and laughed.

"A shadow thing would not say that," he cried, and then a little frown came to his face. "But it cannot be that you are alone in a place like this–you are only a papoose. Where are the ones who have come with you?"

"No one is with me," answered Nah-tee. "Not anyone at all. Maybe I am not big–maybe I am only papoose–but I have run away–I am lost," and a little tremble came into her voice, "and very much I am hungry."

The boy looked at her with such great surprise that his mouth opened wide before he spoke again.

"You are lost," he said then, repeating the words that she had said. "Why did you run away to get lost?" But he did not wait for an answer, for a look came into the face of Nah-tee that made the boy jump up quickly and put a blanket on the ground by the fire.

"Sit down here," he said in a very kind voice. "I will give you of that supper in the pot, and afterward we will talk."

And very glad was Nah-tee to sit down and to warm her hands by the fire and to give the dog a little friendly pat on the head when he came near to her and sniffed. And, oh, how good was the taste of that supper in the pot! It was a stew of goat's meat, and the boy took a little pottery cup and filled it with the stew, and Nah-tee almost burned her lips with it in her eagerness to eat it before it was cool. And the piki bread was good, too, and the goat's milk and the dried apricots. Never had any feast tasted better than that supper, and the boy smiled at Nah-tee when three times he had filled her cup with the stew and she had emptied it.

"I think the inside of you is bigger than the outside," he laughed when she had finished. "You must be very careful that a cactus needle does not stick you this night."

"Why should I be careful of that?" asked Nah-tee, with her eyes very big in surprise.

"Because I think you would pop right open like a little puffball," said the boy, and he grinned so that his teeth flashed in the firelight. And Nah-tee gave a little giggle at his words–for she could laugh now. She felt very warm and comfortable on the outside and on the inside, too, and this was a nice boy–she liked the way his eyes squeezed up when he smiled, and his voice was pleasant, and he had kind ways.

"Why are you up here?" she asked him then, as she watched the little flames of the fire dance high into the air. "Why are you up here when your sheep are down there?" and she pointed to the little draw below them where she could just see the sheep huddled together in a shadowy mass, with two or three goats standing near, and the watching dogs moving restlessly around them.

"I do not like the cold wind," he answered. "It is good for the sheep down there, for there is grass and they can lie close together and be warm; but here it is best for my fire in the rocks, and there is no wind–I do not like the wind."

"It would be a nice thing," said Nah-tee, with a look in her eyes that did not see things that were there, "if there would be big birds so big they could spread their wings like a hogan wall and keep the wind away."

The boy stared at her.

"Why do you say that?" he asked. "Did anyone ever see birds like that?"

"Oh, no," answered Nah-tee quickly, "but always I think things." She looked at him and smiled. "It is nice to think things," she said; "not the outside things–I do not think about them very much–but the inside things, they are nice," and the look in the boy's eyes made her smile again. But then a look of trouble came into her face. "When it is light I must go," she said. "Will you help me, boy, to find the place where my people are?"

"Yes," he nodded, "when it is light we will go," for Nah-tee had told him of the camp place in the desert where her people were waiting, and of the fight and of the way she had come, and he had said that surely there would be no fight now, and her father would be waiting with anxious thoughts, but they could not find the way while it was dark, and, besides, he could not leave his sheep when there was no one to stay with them.

"When it is light I will go and find a friend," he said. "I have a friend who will stay with my sheep, and then we will go and find your people." And after that Nah-tee could not ever remember one thing more that happened that night. She felt very comfortable, and the fire made crackly, sleepy sounds that seemed to say words to her, but she could not tell what the words were. And then–very suddenly–the boy was smiling into her face, and bright sunlight was shining on the red band about his head. Nah-tee blinked at the brightness of it and put her hand to her eyes, and then, when she looked at the desert, she saw that the moonlight had all gone and everything was sparkly fresh in a new day, and the sheep were bobbing in and out among the rocks to find bits of green to eat, and the dogs running around and around them, barking joyously and glad to be alive. And for a little Nah-tee forgot that she was in a strange place and jumped up to run with the sheep–and then she remembered and the shiny look went from her eyes. The boy was holding a piece of meat on a stick over the fire, and he nodded at her in a friendly way.

"My friend will come," he said. "He has told me he will care for my sheep, and you and I will go and find your camp place. Look, there is my pony–there," and he nodded to where the pony was nibbling grass in the rocks. Nah-tee had not seen him before, and he looked to be a very nice pony. He had a look in his eyes when he lifted his head that seemed to say:

"When you are ready, I am ready, to go anywhere!" and Nah-tee wished suddenly that she could ride on a pony like that. Always she had ridden in a wagon or on a fat little burro that jogged along on very stiff legs. It would be wonderful to go flying along on a pony that looked as if he could go like the wind. And while she ate her breakfast she thought of nothing but that pony and listened for the funny little nicker sound he made when he raised his head to look at them. Almost she forgot to think about what she might find when she rode to the camp place in the desert. But the boy did not forget, and there was a worry look on his face that Nah-tee did not see.

"I am called Moyo," he said when they had eaten, "and if you will tell me what to call you we will go now. See, here is my friend."

The other boy had come so quietly that Nah-tee jumped when she saw him standing close by the fire beside Moyo, but she did not fear him at all, for he was a very little boy, almost as small as she was. and always he was smiling, and he spoke almost not at all.

"Come, then, Nah-tee," cried Moyo, when she had told him her name, and he lifted her high onto the bare back of the pony and jumped up in front of her almost before she knew what was happening; and he told her to put her hands about his waist and to hold very tight–and away they went–flying just as Nah-tee had thought the pony would go, like the wings of the wind. She had never dreamed of herself going like this–so high from the ground! A little she was frightened, but Moyo told her to hold tight and called little words to his pony. And sage and rocks and trees went past like shadows in a dream.

"Oo-ooh!" cried Nah-tee, and she made the word long like a song of the wind. "How quickly we will be there now, Moyo." And down into the little washes they rode–the washes that she remembered so well; but how different they looked in the sunlight–and up again through the sage and through country where there were small trees growing–jack oaks and greasewood–and past high, pointed rocks that looked like the tepees of some giant race–and on–and on; but they did not come to any camp place that was like the camp place of her people.

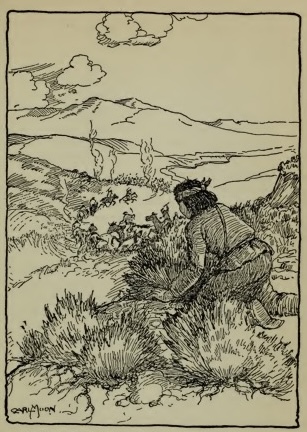

"We will go the other way," said Moyo, with a little frown between his eyes. "Maybe we have come the wrong way." And he turned the pony around, and they rode back very much the way they had come, and then on in the other direction through desert where there were no trees at all, only the tall cactus and sagebrush, and wide stretches of sand and rocks where they could see great distances in every direction; and they looked carefully, both of them, with their hands to their eyes to keep out the bright light of the sun, but still there was no sign of camp fire or shelter anywhere in all that place–not any that they could see.

"There are very many big rocks," said Moyo. "Maybe if we go in a high place we can see better"; and they rode until they found a hill that was higher than the other hills, and from there they looked to the north and south and to the east and west, but they could see nothing at all but desert, and a queer feeling began to grow in the heart of Nah-tee, and a deeper frown place to come on the face of Moyo.

"It cannot be a great way that you came," he said at last. "You could not come very far without a horse. But see how there is no camp anywhere in this desert."

The lip of Nah-tee trembled a very little bit, but she bit it hard with her teeth–she would not let a boy see that she was frightened–not ever would she do a thing like that; and besides, it was only that they had not looked in the right place–somewhere in the desert was that home camp.

"I think," she said slowly, in a voice she could not keep from being a little trembly, "I think we have not looked in that place," and she pointed with a very shaky little finger to a sort of valley that ran between two low hills, and there were more trees there than in other directions. Moyo looked at her quickly, and she did not understand the half smile that came to his face and went away again.

"Well," he said slowly, and he turned his face away so that she could not see his eyes, "we will go there, then." And the pony seemed to go faster even than before when they turned toward the little valley, but Nah-tee did not feel now that they were flying, and she opened her eyes very wide so that the wind would dry the wet feeling that was in them. It could not be a true thing that that camp had gone like a cloud shadow on the sage–things like that did not happen; it must be here in this little valley place. And then she closed her eyes so that she could open them again when they were near. But when she looked she could not help giving a little jump of surprise. Now she could understand why Moyo had looked at her so queerly–they were back in the very same place they had started from. There were the sheep and the dogs and the little fire in the rocks still burning, and now the shiny drops came to the eyes of Nah-tee and rolled splashing down her cheeks–she could not help it.

But she would not have cried–not one single drop–if she had known the things that were to happen! For, if she had not run away, and if the camp had not been lost–But you shall see those things that are to happen, and you shall see how she should not have cried!

CHAPTER II

THE RACE WITH THE STORM

Blow–winds of the desert–blow!

And rattle the pinyons as you go!

Blow the clouds into shiny sails–

And fluff the fur in the little hares' tails!

And pile the tumbleweeds in a row–

Blow–winds of the desert–blow!

WHEN she got down off the back of the horse Nah-tee felt very trembly and queer. Her legs did not want to stand up, and she sat down quickly on a big rock. The two boys looked at her, but they did not laugh and she was glad of that. She did not think it was a laugh thing to be lost and to have shaky legs. But very quickly she had other things to think about, for the new boy–Moyo said he was called Tashi–was talking to Moyo in a voice that showed he was greatly excited, and the words that he said stumbled over one another so that Nah-tee had to listen very carefully to understand–but she did listen, for she thought it might be about her people that he spoke.

"A man came," he said to Moyo, "while you were gone a man came. He rode on a burro with many bundles on top, and he was fat, and he asked for a drink of goat's milk. Then he spoke of the man from the white teaching place–where they teach Indians to be like white people."

"I know," said Moyo, and he made his mouth tight. "I know that place."

"He said," went on the other, "he said the white man is looking for Indian children–all the Indian children there are, and he will take them to the place away from their own people–oh, very far away–and when they come back, in many years, maybe, they will look like white people and talk like white people, and this white man says he can make them all to go."

"Me he cannot make to go!" cried Nah-tee. "I do not want to be like white people–then my father and my mother would not know it was me!"

Moyo looked at her quickly, but his eyes did not see her, he was looking far away with thought in his eyes.

"I want to be Indian always," he said slowly. "I want to be like my father–he is very good, and he is Indian."

"But what can we do?" asked Tashi. "The white man will come–this man says that he will come very soon–and always the Indian must do what the white man says."

"There are very many places we can go," answered Moyo. "Near here are hills and cañons and cave places–the white men do not know about those places–we will go there."

"There is to be a big dance on the high mesa," spoke Tashi again in a very different voice. "All the Indians everywhere are going to that dance–the man on the burro was going–it will last for many days, and there will be good things to eat. I think, maybe, all the Indians in the world will be there."

Nah-tee forgot the trembly feeling in her legs and jumped up from the rock where she had been sitting.

"Maybe it is there that my people have gone," she cried. "Maybe they have traveled all this time to be at that dance. Will you take me to that place, Moyo? Will you take me now?"

Moyo looked at her doubtfully.

"Maybe that is true," he said, but he spoke very slowly, "but that big mesa is a very far place–never have I been there, and I cannot leave the sheep for so great a time."

The face of Nah-tee turned very sad again, and she looked down at the ground not to show the tears that had come suddenly to her eyes, but the other boy spoke quickly.

"I will put my sheep with yours," he said to Moyo, "and there are goats and dogs to keep the coyotes away. I will stay with the sheep and you can go–it is not well for a little papoose to be so great a time away from her mother."

"Oh," cried Nah-tee, "how you are nice. And now–will you go, Moyo–will you take me to that big mesa?"

"But yet it is far," answered Moyo, "and the way is strange to me, but maybe we can find it. Never have I seen a dance big like that dance will be."

"Then we will go now!" cried Nah-tee, and she jumped up and down in excitement. "Now I will find my own people, and we will ride again on that pony!"

"Yes," said Moyo, "we will go now, and we will ride on that pony, but we must have food to eat and a blanket for you to sleep on–it is a very great way to that mesa–I think you do not know how it is far."

But the far part did not worry Nah-tee, not even a little bit, for a very long time she had traveled over the desert, and it was a thing she knew well; and all the fear thoughts had gone now, for she felt very sure that she would find the home people on that high mesa, and there was all the excitement of long rides on that pony before her and of new things to see, and the dance with the many exciting things at the end of the journey. Her eyes sparkled at the thought of it, and then a new thought came.

"Do you think that white man will be there?" she asked suddenly. "Did he ride to the mesa, Tashi?" But Tashi shook his head very positively.

"No, the fat one said that he went to the Trading Post–I think he will not go to the mesa this time–he was going the other way. I think this time you will not see him if you go to the mesa."

"That is good," said Moyo, and he breathed with relief. "Look, I have here food–goat's meat and piki bread, and we will take water in a bottle. Now I am ready. See, I have tied the blanket about my pony. It will be more soft for you to ride that way, and you will have it for the night. Come, Nah-tee," and then he swung her high in the air as before–he was very strong–and again they were flying over the desert, and it seemed to Nah-tee that the little hoofs of the pony hardly touched the ground. They flew past the sheep in no time at all, and left Tashi, grinning, far behind in a flash. And then it seemed that in all that great desert only they were alive–nothing else moved–except the high trail of dust that danced behind them and the little sticks and stones that flicked from the pony's feet. But it was not the sort of loneliness that mattered–it was not the sort that Nah-tee had felt when she was high in her tree in the night–this was a jolly loneliness–it was a sparkly daytime loneliness, and there wasn't a single fear thought hiding away anywhere. Somehow, there was a smile in everything. The little leaves and cones on the trees seemed to wave to Nah-tee as she passed, and she could catch glimpses, every once in a while, of the white stumpy tail of a little hare as it dodged under the sage, and the air was very good with a smell of pine and sage in it that blew down from the far-away hills. And always in the ears of Nah-tee was the whisper of good things to come–exciting things.

She bounced up and down on the pony–not yet had she learned to ride very well–but Moyo turned and smiled at her when she bounced, and he told her how to hold tight to the strong jacket that he wore, and not once did she fear that she would fall.

When they had ridden for a little way with no noise but the thud of the pony's feet on the hard earth, another sound came to them from the trail ahead, and Moyo laughed as he heard it.

"WHACK!" came that sound from ahead, and then it was followed by words in a high shrill voice: "Ai–ee, but thou art lazy! On, on–or never will we reach that place!" and then, "WHACK!" came the sound again, and it did not need more words to tell to Moyo and Nah-tee that the fat man who had stopped at their camp place was very close ahead. And over a little rise they came upon him riding very slowly in a cloud of dust, and the look on his face was not a happy look. He was a very fat man, and looked to be much larger than the very small, very fuzzy burro on which he was riding, and besides himself there were bundles of wood and sacks of things piled high on the back of the little animal. Nah-tee made a little pity sound with her mouth when she saw him, and Moyo said, very low so that only she could hear:

"It is not a strange thing that the burro will not go–I, myself, would not carry so great a load. And look how fat and lazy is the man. Maybe he would not be so fat if he could be that burro for a little while." When they came close to him the man called out to Moyo:

"How is it that you can make your pony to go with two that ride him and this lazy creature will not go with only one on his back?"

Moyo made his pony to stand still and looked for a moment at the man, and Nah-tee could not understand the look that was in his eyes–he did not smile, but there was a twinkle somewhere that Nah-tee could feel, and she watched very closely to see what he would do.

"I can make that burro to go," he said then, very slowly, to the man, "I have a secret way that will make him to go–if you would like."

"What is that?" asked the man quickly, and he looked up at Moyo with eyes very wide and round. "Surely I would like him to go–tell me that secret way."

Moyo jumped down from his pony and walked over to the man.

"You must get down and hold the rope while I speak to him," he said. The man dropped his mouth open when Moyo said that, and almost it seemed as if his eyes would pop out of their places in his head.

"You would speak," he said, and the words would not come easily. "You would speak to him–to that burro?"

Moyo only nodded to that, and Nah-tee was almost as surprised as was the man, but Moyo only waited a little impatiently for the man to get down, which he did in a moment, but as if he moved in a dream, and not once did he take his eyes from the eyes of Moyo. The burro stood on three legs now, as if he were going to sleep. His head and his ears drooped toward the ground, and his eyes were half-closed, but Moyo walked to him and lifted one ear very carefully and whispered to him words that the others could not hear, but like magic came the change in that burro. Up came his head with a quick jerk that almost pulled the rope out of the hand of his master, and his eyes opened very wide with a look of surprise and alarm and one ear shot up and the other one down, and then–in stiff-legged, quick jumps he was off down the road–jerking the fat man almost off his feet at the very start, but making him take queer, long steps that finally broke into a fast, jumpy run to keep up at all. He was too out of breath, that fat man, right away, to say anything at all but, "HI–HI–!" and he could not let go of the rope, he was going too fast–so fast that if he did let go he would fall flat in the dust–but to hold on he had to run faster and faster to keep up with that burro, who was now going like a wild thing over the dusty trail. Nah-tee could hardly believe the thing that she saw, and she called out to Moyo:

"He will fall–that man. Look, how he cannot run like that."

"He will not fall," answered Moyo with a wide grin on his face, "and it is very good for him to run fast, he will not be so fat."

"But how did you make that burro to go like that?" and Nah-tee looked at Moyo as if she saw him now for the first time. "It is a magic–a thing like that."

Moyo pushed a little stick with the toe of his shoe and did not look up at Nah-tee.

"It is not magic," he answered, but he did not say more than that. And the burro and the fat man were altogether out of sight now, but back on the trail very faintly came that voice raised high in protest:

"HI–HI–ai–ee!"

"Why did he go, if it was not a magic thing?" asked Nah-tee, and Moyo looked up at her with the twinkle very plain now in his eyes.

"Maybe it is magic," he said this time, "but it was only a little bur that I put in his ear."

"Oh," cried Nah-tee, "it will hurt him."

"No," answered Moyo, "it will not hurt him at all, it will only tickle him. Right now I think he is laughing in burro talk, and he is very glad to have that fat man off his back. The bur will come out easily when he stops and rubs his ear against a tree, and the fat man will feel good for the run. He will reach the place where he is going more quickly, and he will not be so lazy, maybe, another time."

A little smile came into the eyes of Nah-tee then as she thought of the look she had seen on the face of that fat man when the burro pulled him, jumping, down the trail.

"Look, how everything is running," she cried suddenly to Moyo as some little rabbits dodged into the sage not very far away. And Moyo just as suddenly grew very grave.

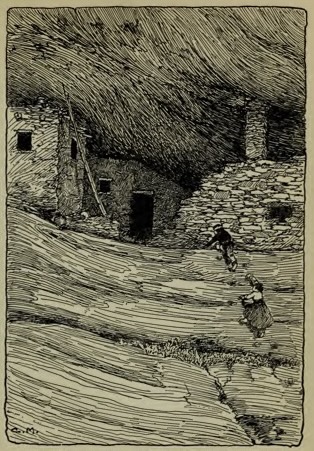

"I saw a coyote, too, a little while ago," he said, and looked up at the sky with a little troubled frown on his face. "The wind is very strange," he said. "And look at those queer clouds–we must get somewhere that is safe. There will be a storm soon, and a very bad storm. I have been taught the ways of the desert, and see how all the desert animals are running for shelter."

The wind was coming in queer, short puffs now–a warm puff and then one that was cold as ice–and far away a sort of sighing sound seemed to come from the very sky, and sand blew in their faces with a sharp stinging feeling. Moyo climbed up on the pony and turned his head away from the wind.

"We will find a place to stay," he cried above the noise of the wind, "until the storm is gone–over there." And he pointed to high, rocky walls far to one side of the way they had been going. "We will find cave places that will be safe and dry." And he made the pony go very fast again. Just back of them the raindrops began to fall, and the sky grew very dark with a yellow color. The wind was steadily cold now, and did not blow in puffs, and the sound of thunder came from far away but was growing steadily nearer.

"We will go fast," cried Moyo again, and he had to shout very loud to make his voice heard above the howling of the wind, "and maybe we can keep away from the storm." And he kicked the pony with his heels and called to him and they went so fast that Nah-tee closed her eyes tight to keep from growing dizzy. But it was very exciting. The rain was falling in a steady sheet now just behind them, but always they kept a little way ahead of it and they were yet completely dry.

"Hi–yi!" cried Moyo as they flew along. "Now we do not belong to the ground–look how we are a part of the storm. We are the little brothers of the wind, and we can go just as fast as he can." And a great boom of thunder almost drowned his words. Dust and leaves swirled about them, and tumbleweeds flew past in great round balls only to pile up in big heaps when they came to rocks or trees they could not pass. On–on they flew–just ahead of the storm–and now the walls of rock they had seen in the distance were growing ever nearer.

"We did not pass that fat man," shouted Nah-tee to Moyo. "Where do you think he has gone?"

"We do not go the trail that he has gone," said Moyo. "We do not go that trail now–now we go to find a cave place that will keep us from the wet of the storm. When that is gone we will find the trail

On–on they flew–just ahead of the storm.

again that leads to the big mesa." And just then the first drops of rain caught up with them. Moyo shouted more loudly to the pony and slapped him with his hands, but he could not go more quickly than he was going, and with a louder howl than any that had gone before, the storm swirled around them, and they felt now very truly that they were a part of it. The noise was loud, and they could hardly see at all for the dark and the water that was dashed into their eyes, and the thunder crashed and boomed so loudly that it seemed the very skies were falling. Soon Nah-tee could just barely see great walls of blacker dark about them, and she knew that they were riding into a cañon. Moyo held his hand to his eyes to keep the rain out and looked carefully for a place of shelter, but not yet did they come to one. Many times they came right up to places that seemed to be the end of the cañon, great walls of rock, but always there was an open place through which they could go, and another big cañon, just like the one through which they had come, stretched out ahead. The brave little pony did not falter once, but pushed on as fast as he could go and answered to every guiding touch from Moyo. It seemed to Nah-tee that for a very long time they rode blindly without seeing where they were going, and she was growing cold as ice and very wet and uncomfortable when Moyo gave a shout that showed he had seen something, and he turned the pony and led him up to one of the stone walls and called to Nah-tee to climb down.

"It is very easy to get to that place," he cried to her. "'See, there is a big cave place up there." And Nah-tee saw, opening deep into the rock, a cave place that looked very black and big in this dim light. It was not hard to climb up, there was a long, rough slant of rock that led right to the open side of the cave; and when they had hobbled the pony under a slanting wall of rock where he was protected from the storm, they climbed quickly up. But they were breathless and not quite so cold when they reached the top. It seemed to be a large cave that went back into the rocky wall of the cañon itself, and below it was a ledge of rock like a little shelf where a sentinel could stand. They could not see how far back into the rock the cave went, for it was dark as the blackest night in there, but they quickly did see things out on the shelf of rock; and just in the opening, where it was not dark, it looked as if other people had been here, for the top of the cave was black with smoke, and the ashes of an old fire still held their shape. And it was dry on the inside of this place, and the cold wind did not come in; and better than all of these things, there were many dry sticks lying on the rocky floor.

"OOH! How I am cold!" cried Nah-tee. "Now we can have a fire and get warm and dry."

Moyo leaned over and picked up one of the sticks quickly, and then he did a very queer thing. He did not make a great pile of them, as Nah-tee thought he would, but he looked very carefully at the stick and picked up another and looked at that in the same strange way. Then he called in a low voice to Nah-tee:

"Do not move–wait for a moment in that place"; and then he leaned down and took a step forward and looked for a long time–it seemed a great while to Nah-tee–into the black dark of the back of the cave. Then he threw one of the sticks as far back into the shadows as he could and looked and seemed to be listening–but nothing at all happened, and he drew a deep breath and stood up.

"What is it?" cried Nah-tee. "What have you seen?"

"Nothing," answered Moyo, but he did not look at Nah-tee. "There is nothing in the cave, and we will build a fire quickly." He found many pieces of wood that were dry, and he took a very short time to pile them into a neat heap; and then he made a fire with the fire stick that he carried always in a fold of the cloth at his waist. To Nah-tee it was always a magic thing to see the whirling fire stick and the first little sparks that seemed to come from nowhere at all. And very quickly the flames were crackling and leaping in the very way they did in the camp fire at the home place, and Nah-tee held her little cold hands to the cheery blaze and watched the warm light creep farther and farther back into the strange corners of the cave–and Moyo, too, watched those shadows creeping back into the darkest parts of the cave, and he looked very often over the edge of the little rocky shelf down into the cañon below.

"We must gather more wood for the fire," he said in a little while, "and we must make pieces for torches. But now we will have supper. We are very safe while the fire burns high."

"Oh, yes," laughed Nah-tee, for the fire had made a happy feeling come into her heart, and now she was getting dry again. "Oh, yes, the fire will keep us safe and warm from all the storm." Moyo looked at her a little strangely, but he did not speak then.

And happier and happier grew that feeling in the heart of Nah-tee, especially when Moyo put some of the goat meat on a sharp stick and frizzled it over the fire and they ate a supper that tasted all the better for the howling of the storm outside.

And then, even more suddenly than it had begun, the wind died down and the rain stopped and the sky began to grow lighter, until the sun sent shining streamers that touched with red gold the rocks high on the cañon wall; for it was late in the day, and very soon the gold went away and only the pink of the afterglow remained, and that, too, faded quickly, and almost before they knew it, night had come. Nah-tee folded her arms over her knees and watched the fire with a great content.

"I am glad we have come," she said. "This is a nice camp place for this night, and when day comes we will go to the big mesa."

"We will start to go to the big mesa when day comes," answered Moyo, "but not for very long will we get there–I told you how it is far."

A sharp sound came from down in the cañon, a clatter as of hoofs on rock.

"It is the pony," cried Moyo, and jumped to his feet in an instant, snatching a blazing piece of tree branch from the fire. A cold feeling ran down the back of Nah-tee, and she, too, jumped to her feet and stood listening, uncertain just what to do.

"Stay here," said Moyo quickly. "Do not move from this fire–I will come back"; and he ran quickly down the slant of rock that led to the cañon floor waving high in the air the blazing torch that he carried. Nah-tee held her breath and listened, and quickly she heard the voice of Moyo speaking words of quiet to the pony, and then in a little he came back up the rocky way leading the pony by a rope–it did not take long to get him up.

"He will be better here," said Moyo, and tied the rope of the pony around a large rock so that he could not get away. Nah-tee watched him with big eyes.

"What is it, Moyo?" she asked then, and she was almost breathless, as if she had been running.

"It is nothing," answered Moyo in a voice that he tried to make sound as it usually did, but a very little it trembled, and Nah-tee could hear the tremble. "I think maybe there are coyotes down there, but the fire will frighten them away," he said, and a great relief came to Nah-tee when he said that, for she had no fear of coyotes–but it was not coyotes that Moyo feared were in the cañon. When first he had come to the cave place he had seen the things that Nah-tee thought were little sticks–but he knew they were not little sticks–they were pieces of bone that some animal had left, and they were not very old, some of them–and coyotes did not live in caves like this–it was mountain lions that Moyo listened for. He knew they often lived in cañons just like this one, and any moment he expected to see their green eyes glaring at him from the dark or to hear the quiet night made fearful by their cry. But Nah-tee must not know this–girls did not have to know such things when others stronger than themselves were there to protect them. And, besides, mountain lions were great cowards and would not come near to the light of a fire. So Moyo gathered many sticks in a pile on the rocky shelf and was very glad that some strong wind had blown them down into the cañon from the trees that grew above. And Nah-tee watched him with a little troubled doubt in her eyes, but already the fire and the supper had made her drowsy, and it was not long before she lay down on the blanket, now warm and dry, and went fast asleep. But Moyo did not sleep–not for a very long time–and not then did he think he slept! But after a while the fire seemed, somehow, to be the flicker of his own fire at home, and the crackly sound of the blaze faded into the rhythmic sound of his mother grinding com–and Moyo was dreaming–and only the fire kept watch.

CHAPTER III

THE MANY-WALLED CAÑON

Some giants must have come–in long ago,

To build these rocky walls–where eagles fly;

Some mighty ones–I think it must be so–

Who else would want their homes to be so high?

WITH the first gray light of dawn Moyo awoke with a start and jumped to his feet. The fire was almost as gray as the dawn, and the air had a frosty nip to it, but it was not the cold that had made him jump to his feet with his heart in his mouth–he had dreamed of mountain lions slinking nearer and nearer to the cave place, and not yet had the dream feeling altogether left him. But there was no living thing that he could see in the cañon and the pony looked at him with a little nicker of surprise and hunger, and ponies always know and have a way of telling to others when wild animals are about, so Moyo very quickly gathered more sticks and built up the fire again, and by that time Nah-tee sat up on her blanket with round eyes very big and wide and blinked for a moment until she remembered the place where she was, and then she smiled at Moyo and jumped as quickly to her feet as he had done.

"The coyotes did not come," she cried, "and nothing else came–and I think I am more hungry than any coyote ever was!" and she was very glad to get the piki bread and meat that Moyo gave her. There was grain, too, to give the pony from a little bag they had brought for him, and they gave him a drink of water from their own bottle. And after that Nah-tee could not keep still–she threw up her head as the pony did at times.

"Oh, how the air is good!" she cried, "and all washed clean with the wind and rain. And we will ride again to-day and see things–and I think never was I so happy!" and she jumped up and down and in little circles all the way round the fire, and some of the wood that Moyo had gathered was scattered again by her little feet.

"Can you not stay still for one moment?" he cried with some annoyance in his voice, the very first that he had shown, for it had not been easy to gather that wood. "Can you not stay still for one

Nah-tee jumped in little circles all the way round the fire.

single little moment?" But a spirit of mischief had come into Nah-tee, and she made a face at him.

"I can stay still for one moment and for more than one moment, but this is not the one," she said. "This is the moment when I am happy and my feet have a dance feeling in them. I will help you to gather that wood in a little while, maybe, but look, Moyo, how it is good to dance now."

He sat back on his heels and looked up at her with a little frown on his face. It was not a real frown, but he tried hard to make it look like one.

"I think never you have been taught to mind," he said then. "Maybe that is a thing they do not teach in the desert where you live. I have been taught always that it is bad not to mind the ones who are older."

Nah-tee was suddenly quiet and opened her eyes very wide.

"Yes, I have been taught that thing, too," she said in a very small voice, "but I did not know–that is a funny thing–I did not know that you were an older one." There was still a look of mischief in her eyes and Moyo made his look and his voice very solemn, so that the mischief would not again go into her feet.

"Yes, I am an older one," he said very seriously, "and I will tell you why always you must mind the older ones."

"I know," said Nah-tee eagerly, "I know why."

"But maybe," said Moyo, "maybe the 'why' you know is not the 'why' of my people. I will tell you my 'why' and then, afterward, if it is not the same one, you can tell me the 'why' that you have been told."

Nah-tee sat down on her blanket and put her hands together and looked down like a very well-behaved little girl and said:

"My ears are open, my father, I will listen."

A little quiver came to the lips of Moyo, but he did not let it get as far as a smile, and he, too, sat down on a rock by the fire.

"This is the way it was told to me by my father," he began, "and before that by his father, and it goes away back to the time when there was only one tribe of people in all the earth and that was a very, very great while ago." Nah-tee nodded her head but did not take her eyes from the toes of her moccasins and Moyo knew that she was trying to tease him; but he could not be teased so easily as that, and went on in the same tone of voice: "Out on the edge of the desert in a queer little hogan lived an old Spider-woman. All humped up and black she was, and so old that her hair was as white as the silk stuff of the milkweed seed, but her eyes were black and shiny as stars, and she knew much magic. At first the little ones had fear of her, for they had heard tales of how she stole children and they never were seen again; but after a while they did not fear her, as she gave to them little seed cakes to eat and spoke only words that were honey sweet and soft. 'Do not go near the hogan of that old Spider-woman,' said the mothers and the fathers to the children. 'She is an evil one, and bad things will happen if you go there.' But not yet had the children learned that always the older ones know more than they, and nothing at all bad happened when they went to the hogan, so they laughed when the mothers said that and called back to them: 'No bad thing will happen to us–that Spider-woman is very little and old, and we have no fear of her.' And they ate her seed cakes and laughed at the joke things she told them, but not ever would they go into her house–that was a thing they would not do, even though she told them of the very fine things that were there : the bow made of the strongest ash wood, fit for a warrior or a hunter of big game, and the blue sky stones that could be traded for many wonderful things, and the soft woven blankets that no cold wind could blow through. But she could not get them to go into the hogan, for something told them that they would not be safe there as they were out in the open air. And then came the time of a great feast. It was the feast of the harvest, when dancers and runners came from the very farthest camping places, and there were games and races and many ceremonies." Nah-tee wriggled.

"Maybe like the dance they will have at the big mesa," she cried, and altogether she had forgotten to tease Moyo and listened with big eyes to the tale he was telling. He nodded in answer and went on:

"The games were for everyone, big ones and little ones, and there were very fine prizes given, and everyone wanted to win those prizes. The best prizes of all were to go for the great race, and everyone was to run in that race. The little ones were in the front, and back of them the women, and farther back still were the men. Before the very day of the feast there was much running for practice, and one young boy watched the others run, and in his eyes there was a very eager look to win. He was the only one of all the children who did not go out to the hogan of the old Spider- woman–'The older ones have said not to go, and they are wiser than we,' he said, and the others laughed at him and jeered and pointed the finger: 'Hi! Brave-young-man-tied-to-the-papoose-carrier-of-his-mother,' they cried, 'See, how he is afraid of the old Spider-woman–Yi! Yi! Brave one! But surely you will win all of the prizes with to-morrow's sun because of the bravery that is in you!'

"'Maybe it is more brave not to go to the Spider-woman than to go,' said an old man who saw what happened, but he said the words inside himself, and no one heard.

"But others saw it, too, and they nodded wisely to one another. And the children who did not mind ran out again to the hogan of the Spider-woman, and to each one she spoke secretly and gave to him a very small bag with a little yellow powder in it.

"'This is a magic charm,' she said, 'a very secret and very strong magic. On the day of that race, at the very start of it, you must swallow this powder, and then you will be more swift than any man there and will surely win.' And each one who was given the magic charm thought he was the only one, and went away with his head in a cloud to think that he would win that race.

"And then, on the very day of the race, there was great excitement. Never had there been such excitement as on that day; and each one of the children looked at the others with the thought that how sad would the other one be when the day was over and the race lost for him–all but the one boy who did not have a magic charm–he looked only straight ahead to the place where they were to run the race, and his thoughts sent only a little prayer to the Great Spirit for speed and the strength to win. The old Spider-woman was there watching, and there was a greedy look in her black shiny eyes that was not good to see.

"And then came the moment when the word was given to start that race, and then–a very strange thing happened–for when the word was given, of all the children only the boy who had minded leaped forward down the track, the others, every one, put to his mouth the little charm bag and stood for an instant while the powder went down his throat–and then–a great shout went up from everyone watching, and louder than all shouted the old Spider-woman, and leaped and sang in joy–for where there had been children standing just a moment ago were now only little black spiders running back and forth and jumping up and down in confusion. The magic had been spider magic, and because they had not minded the older ones the children had put themselves in the power of the Spider-woman, and the boy who had minded won the race, and all the prizes were given to him. And never, in all that tribe, has there been a child since who has not minded the words of the older ones.

"And now," said Moyo, with a grin for Nah-tee, "is that the thing the children of your people are told when they are taught to mind the words of the older ones?"

"No–o–o," answered Nah-tee slowly, and she drew a deep breath. "I like that tale, and I like how the good boy won the race, but they have another tale with my people. Maybe I cannot tell it in the way the Wise men have told it, I do not know the words to tell it that way, but I will tell it to you the way it is in my thoughts."

"Yes," said Moyo, "tell it that way." And he put some more sticks on the fire and sat down to listen very carefully; but just as he did that a sharp click of falling stone came plainly from the cañon below, and they both jumped to their feet in quick alarm. Nah-tee was going to look over the edge, but Moyo held her firmly back and put his finger to his lips.

"Be very quiet," he said close to her ear. "I will see–you must stay here"; and he crept very cautiously to the edge of the little shelf and looked over. But there was nothing to see at all. There were many rocks in the cañon, and almost anything could hide behind them, and in some places there were tall pillars of stone close to the cañon walls that rose almost to the tops of the walls themselves. Everywhere Moyo felt that there might be eyes watching–yellow animal eyes or keen human ones–and he did not like the feeling, it made a shivery coldness run down his back that was not exactly fear, but it was not a good feeling. But, he reasoned, if animals were hiding they were not the kind he need fear, and they would run if he threw a piece of blazing wood at them, and why should he fear anything else? He stood up suddenly and gave a little laugh at the thought.

"I think there is a fear magic in dark places," he said, "and it is dark in this cañon. See how the sun goes right over the top and does not come down inside. Let us go, Nah-tee. I think the desert is a better place." Nah-tee gave a quick little breath of relief at his words.

"Then you do not have fear for the thing that made that noise?" she asked, and there was a shine in her eyes as she looked at Moyo. She thought he was very brave, and it made her feel very much safer when he did not fear.

"No, I have no fear of a thing that is nothing," said Moyo with a toss of his head. He was very glad that Nah-tee thought that he was brave; it made it much easier for him to act that way. "Maybe the storm made loose a rock somewhere," he went on, "and it fell down–that is all I think it was." But very much he wanted to get away from this cave place. There was not wood enough to last a great while, and lions might come back to their own place if there was nothing to frighten them away. And then, too, the pony many times lifted his head into the air and twitched his ears first this way and then that, as if always he were listening, and Moyo did not like that–why should he listen if there was not something to hear?

"I think we will go now," he said slowly, and he listened carefully as he said it, but he could not hear anything. He wished he could have ears that heard things as a pony did. "We will go now and see if we cannot go quickly over the desert and reach the big mesa," and he felt the little food bag with his fingers and knew that there was very little left in it.

"I am ready," answered Nah-tee. Always she was ready to go anywhere, and much she liked to ride the pony. They did not put out the fire, for there was nothing it could burn but the little sticks Moyo had collected, and he thought it might be well to have some sticks burning if he should have a quick need for them. They led the pony down the little slant of rock and were soon on his back again, but they found they had to go slowly and carefully on the floor of the cañon, for the sand was very soft, and the pony had to pick each step that he took. Nah-tee saw that each print he left filled slowly with water, and very quickly a look of worry came to the face of Moyo when he saw that. He knew what that water meant–it meant quicksand, and any moment they might come to a place too soft to be crossed safely. He knew, as all Indians who live near such places know, that after a storm the beds of many cañons are really rushing rivers with only a thin coating of sand on the top, and any moment that sand might give way.

"Look," said Nah-tee suddenly, "there has been someone else here," and she pointed a little way ahead to where there were fresh prints–footprints of a man's foot–in the sandy floor, filling slowly with water as their own had done. Moyo gave a little cry as he saw them.

"This moment have these prints been made," he said, "for, look, they are not yet filled with water–and–" he stopped quickly and a frown of perplexity came to his face–the prints in the sand stopped as suddenly as they had begun! And there was no place on either side of the narrow cañon that they could see where anyone or anything large enough to make those prints could find shelter.

"What is it?" asked Nah-tee in a voice of wonder, "and where has it gone?" Moyo shook his head and kicked his pony with his heels.

"I think we will go fast," he said, "and get away from this place, and then it will not matter." Nah-tee was silent for a little, and then she said :

"My mother tells me that the Great Spirit is everywhere and this is a part of everywhere."

"I am not afraid," answered Moyo, and he made his voice big, so that it echoed from the cañon walls. "I am not afraid one bit–but–but–I like that desert very much better than this place," and he tried to make the pony go a little faster than he was going. But he kept his eyes very carefully searching the rocks on either side in the cliff walls, and also the sandy floor, but he did not see one living thing–but he saw something else. Something that made him pull back quickly on the rope bridle that guided the pony and draw him over to the very edge of the sand where he felt that the rock was underneath, and there he stopped. The sand had grown suddenly too soft to bear their weight, and even as fast as they had been going, the pony's feet had been sinking deeper and deeper with every step.

"We cannot go any farther," said Moyo, and he could not keep the alarm altogether out of his voice. "Look how the sand is turning into water. Soon this place will be a river in the cañon–I have seen it do that way. We are safe right here on the edge of this rock, but we cannot go anywhere else."

Nah-tee looked at the wet sand and then up at the high walls of the cañon, and it was plain that there was no thought of fear or danger in her mind. Instead a little twinkle came to her eyes.

"But how can we stay here and go to that big mesa, too?" Moyo did not answer her; a sudden thought had come to him.

"Maybe it is because we are too heavy–all the three of us–that we sink into the sand," he said. "Get down from the pony, Nah-tee, and we will see if we each one can go alone." And they both got down, and Moyo gave a little pull to the rope of the pony, leading him out into the sand again. He knew that the pony could tell if it was safe.

"Be ready, Nah-tee," he cried. "You must hold my hand, and we will go if he will go." There was a sharp crash of a falling stone from somewhere high in the cañon wall, and the pony, with a loud, startled snort, leaped into the watery sand, jerking the rope out of the hand of Moyo. He floundered helplessly for a moment, and Moyo, with a shout of fear, thought that he was sinking. "GO!" he cried. "GO, NIKI!" and he clapped his hands and shouted as loudly as he could, and the pony thrashed about with his legs in a very great effort to get out, and in a little he did pull himself higher in the sand, on the other side of the narrow cañon, and then looked back at Moyo as if he would return.

"Oh, he will sink down if he comes back," cried Nah-tee. "Do not let him come back, Moyo"; and even as he stood hesitating the sand seemed to be reaching up for him again.

"Go on!" cried Moyo, though there were almost tears in his voice. "Go on, Niki!" and the pony turned slowly and went stumbling and stepping with great difficulty until he disappeared around a big rock in a bend of the cañon wall. The two children stood for a moment watching where he had gone, and a queer, lonely feeling came to them immediately when he was no longer in sight.

"Do you think," asked Nah-tee, a little timidly, "do you think he will wait for us when he finds a place that he can stand on?"

Moyo did not answer immediately. Already he felt that he had done a very terrible thing. How could he be certain that the pony would find any place to wait–and what would they do now, if they did not have a horse? But very surely that pony would have gone down under the sands if he had tried to return to them. And what had been that sound that had frightened him in the first place? They had not looked then, and now there was nothing at all to see. Moyo tried the sand cautiously now to see if it would bear his weight, but he had very little hope–the pony had gone down too quickly just here. The water rose immediately he touched it, and his foot sank over the shoe top before he could draw it out. A cold feeling came into his heart.

"We will have to wait," he said in a voice that somehow did not want to come out of his throat. "We will have to wait until–until–the sand dries a little." But he knew very well that the sand would not dry–already the water was rising above it, here and there, and soon it would be a rushing stream. No, it would not be safe at all to walk on it now–they would quickly sink beyond any help–they could not do that.

"We will find a place to climb up," he said, and he tried not to show in his voice any of the fear that he felt. "Maybe there is another cave that we will find."

Nah-tee leaned against the rocky wall back of her, and a big tear splashed down her cheek. Moyo saw it, and almost a panic came into his heart.

"Maybe you are hungry," he said. "Here–here is piki bread to eat," and she did not know that the little piece of bread that he put into her hand was the very last bit of their bundle of food, and they did not know, either of them–when they sat down on a narrow ledge of rock to watch the waters rise slowly and surely over the floor of the cañon–that from another place eyes watched them as carefully as they watched the waters.

CHAPTER IV

OVER THE WALL

Shining on the cañon wall,

Splashes of bright sunshine fall,

And a silence, grave and deep,

Never changing, seems to keep

Watch forever over all.

MOYO could not say now that the cañon was a dark place! The golden sunlight splashed down from the rocky walls and turned the creeping water into flashing jewels; and beautiful colors in the rocks themselves, almost hidden when the light was dim, came out now and danced in the sunshine. Fear thoughts could not live when the sun smiled like this, and Nah-tee did not have any at all. She jumped up from her little ledge and gave a shake to her small skirts.

"What shall we do now, Moyo?" were the words that she said. "I think if we go in the very edge of the water the sand will not be soft."

"Look there," said Moyo, and he pointed to the place where, just a little while ago, the pony had disappeared around a bend of the cañon. At that place tall sharp rocks reached from the high walls far out into the center of the cañon, and already the water was swirling swiftly around them.

"I saw that place," he said, "and that was why I stopped here. We could not pass that place, and here the wall is not so steep and we might climb up a little way. No, we cannot go in the edge of the water, we cannot go in the water at all–we can only wait here. Maybe it will not be long–maybe the water will go down before night comes."

"But I do not want to wait here until night comes, there is no place to sleep here," said Nah-tee a little impatiently. "The cave place was a better place to wait–and I think I do not want to wait at all."

"You are little and do not know things," answered Moyo. "I have seen how the waters do. Before this I have seen them rise, and it is not a bad thing to wait. A worse thing might come if we did not wait."

"But why do we not climb up?" asked Nah-tee. "What is at the top of this cañon?"

"We cannot climb where there is no place to put our feet," answered Moyo, but always his eyes were searching the rocky wall, and now he began to work his way cautiously away from the little ledge, feeling with fingers and toes for places to hold to. Nah-tee watched him eagerly. The walls of the cañon were almost straight up and down in most places, as if some great giant had taken a huge knife and cut big slices out of the earth, but in other places there were pinnacles and jagged ridges of rock running clear back and up to the tops of the high, brightly colored walls, and in still other places winds and storms had broken off great slabs and dug into the walls with powerful fingers, making shelves and caves and great cracks, and Moyo hoped to find one of these cracks or caves for a shelter until the waters went away, for he had little hope of climbing to the top of the cañon wall, as Nah-tee had suggested. That looked to be quite an impossible thing from here. Not only was it very high and steep, but the top seemed actually to lean forward and to lend no possible hope of a hold for feet or hands. But still he would not stop trying, not ever, until he came to a place where he could not move forward at all. He moved a little farther now–and a little farther–but there did not seem to be any place toward which he was climbing. Not anywhere could he see a ledge even as small as the one on which Nah-tee was waiting. But still he kept moving, just a little bit at a time, and Nah-tee watched him breathlessly. It surprised him to see how far away she looked–he had come farther than he had expected; and then he stopped suddenly, and quickly moved on again with more assurance. He had come to a place that led up gradually–a place that was much easier to climb; he did not have to go slowly at all now, he almost ran. It was like a trail. Nah-tee cried out when she saw how quickly he climbed now.

"You go now like a mountain sheep," she cried. "I want to come up to that place, too."

"You cannot come over this way if I do not help you," he cried. "Wait there–this has the look of a place where others have been–maybe it is an animal trail. I will see where it goes," and there was a sound of excitement in his voice. He remembered now the sound of that falling rock, the one that had frightened the pony. It had come from high in the cañon wall, and this was high in the cañon wall. He would see. It was a very steep climb, but always there was some place to put his hands and his feet, and in a little he saw that the way led through a big crack and he could not see Nah-tee any more.

"You go now like a mountain sheep," Nah-tee cried.

"Where are you?" she called. "I cannot see where you have gone. Is it a cave place, Moyo?"

"It is a little like a cave place," he called back, but he had to call very loud, and the first time she did not hear him. "I will tell you how it is when I come," he called again, and then he did not call any more, for he knew that she could not hear him. Nah-tee was a little frightened to be left alone like this, but she waited with her eyes always on the place where she had seen Moyo go into the rock–for it looked like that from the place where she was–and almost she held her breath to see if she could hear him again. But there was no sound at all now in all that big place, and she could hear her heart beating as she had heard it in the tree when she was alone in the desert, and she did not like that–it made a very lonely feeling come to her.

"MOYO!" she called with all her strength, but only an echo answered back from the other side of the cañon–very far away It sounded–"Moyo"–and then again as if it were almost a dream-thing–"Moyo" . . .

Nah-tee did not like that at all–and she started to climb over the way Moyo had climbed, but her feet slipped and almost she went down into that swirling stream of water that had been sand such a little while ago, and when she slipped she began to tremble so hard that she knew she could not climb anywhere more, and a feeling came into her throat that she knew very well–it was a feeling that did not go away easily unless she could press her little body close into the tight, warm arms of her mother, and, oh, how she did long to do that!

But Moyo was still climbing. Steadily up went that great crack, until he saw, with a jump of his heart, that he was very near to the top of the wall itself–and then he reached it!–that top–and, as he saw over, his heart fell again, 'way down into the toes of his little buckskin shoes, for he looked over a thin edge of rock down into another cañon almost exactly like the one from which he had just climbed! There were the pinnacles of rock and the splashes of red and blue and yellow and purple where the sun drew out in rich beauty the color of the lime and sandstone and shale, and there was the same flashing stream at the bottom of it, and the caves and cracks and crannies carved by the winds. Only one thing was missing, and that was little Nah-tee on her thin little ledge of rock, waiting for him. "She will want to come up to this place," he thought a little wearily, and then he started back down the way he had come.

Nah-tee had little red spots in her cheeks when he came to her.

"How I am glad you have come back!" she cried, and when he had told her of what he had found she was very greatly excited. "Maybe there will be a good cave in that place," she said in a happy voice, "and maybe we will find food. Let us go quickly, Moyo."

It was not easy to get her over the first part of the way, but when they reached the trail part and the crack, it was very easy and Nah-tee could climb as easily as he climbed. And she cried out when she saw down into that other cañon.

"It is much nicer down there," she cried. "See how there are many cave places, and I can smell the desert from here." She threw back her head and sniffed, and Moyo looked eagerly over to the other rim of the cañon.

"When the waters go down," he said, "we will climb up that other side. Maybe the desert is there."

"I smell camp fires," went on Nah-tee, "and a stew cooking–it is in a big pot. In my mind I can see that pot, and can you not smell the stew?"

Moyo gave a sudden sniff, and his eyes grew big, and he leaned over and studied the cañon carefully again.

"Maybe it is because we are very hungry," he said, and he could not help the little sound of longing that came into his voice.

"Yes, I am very hungry," said Nah-tee wistfully. "Is there any food in the little bag, Moyo?" Moyo took the bit of cloth that had wrapped their food and showed Nah-tee how it was empty.

"But I will get something," he said quickly, when he saw the look in her face. "We will find a place to stay down there, and then I will go and look for food. Maybe there are goats. Many times there are goats living in places like this–and goat milk is good." But inside himself he did not have much hope to find goats, for he had not seen anything alive at all in this cañon. "But where there are sounds," he thought to himself again, "always a sound is made by something, and this trail has the look of something living," but whether of man or beast he could not know. In the other cañon it was not so easy to get down as it had been in the first one, and after a while Moyo knew that somewhere they must have missed the trail–this did not seem like a place now where anyone had ever been before–but they could not climb back, it was too steep for that.

"I am tired," said Nah-tee suddenly, after they had been going for what seemed a very, very long time, and she sat down on a flat rock to rest. It made a hurt place to come in Moyo to see how little she looked and how tired and hungry, but he was doing all that he could think to do, and already the sunshine was gone away from the bottom part of the cañon and was creeping steadily up toward the top and turning very rapidly from gold to a dusky red.

"Can you see any cave place?" asked Nah-tee. "Soon it will be night and we cannot sleep on the side of the wall like spiders," and she tried hard to smile.