A Manhattan Christmas Story

CHAPTER I

NICHOLAS APPEARS

ON a snowy Christmas Eve a Brownie was hiding in the Children's Room of the Public Library, waiting for something wonderful to happen.

The Brownie had lived in this room for years and years and although she knew every nook and cranny of it by daylight, or moonlight, or electric light on ordinary days, on Christmas Eve it was different. Everything was touched with magic and the Brownie's eyes sparkled as she looked over to the Christmas Tree in the Fifth Avenue window and saw a Norwegian Troll climbing down one of its branches.

"Merry Christmas, old Giant," said the Brownie softly, for she knew that Trolls are very shy when they first appear on Christmas Eve. "There's a fine bowl of porridge with thick cream set out for you down in Hudson Park and all your old friends are waiting for the good luck you bring every year."

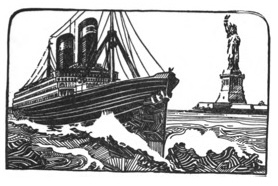

"Skaal, Brownie, my love," the Troll called out. "I saw you down in the Christmas Tree Market the day my ship sailed up North River. I was on the Bridge with the Captain when you picked out this very Christmas Tree and the holly wreaths in the windows and all the hemlock boughs. It seems like home the way you've fixed things for Christmas here. I like the smell of it. I'm coming down."

The Troll gave a leap from the Christmas Tree and landed right beside the Brownie in a corner of the window seat. Just then the Fifth Avenue window swung wide open and in walked a strange boy about eight inches high. His face glowed like a Christmas fire as he shook the snow from his woolen muffler and stood there on the window sill looking out over the red tiled floor.

He was dressed in a pair of long, bright blue cloth breeches reaching to his ankles and a short jacket of brown homespun edged with red. Underneath his jacket a white vest showed just the least little bit. On his head was the blue helmet of a French poilu, on his feet the kind of wooden shoes the boys wear in Holland. His cheeks and lips and nose were bright red and his hands were the kind of hands you want to shake or to fill full of things to give away.

Closing the window very carefully this strange boy climbed down to the little platform below the window seat on which the Brownie was sitting and looked up at her.

"Who are you?" asked the Brownie wonderingly.

"Don't you know me, Brownie? I'm Nicholas."

"Where did you come from, Nicholas?"

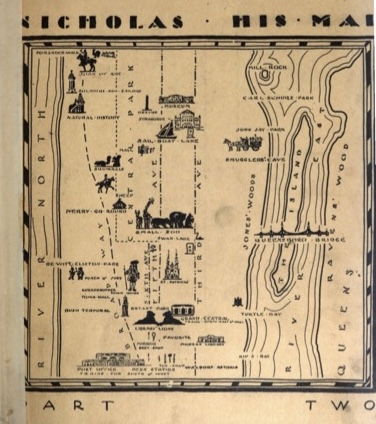

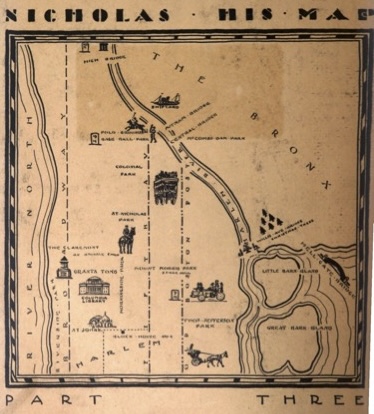

"Straight from the ship. I got off at the Battery and walked along shore to the north until I came to that funny round building down there, then I began to run and the first thing I knew I was right back where I started from. I was in a hurry to get up town so I looked at my map, walked across Battery Park to the Sixth Avenue 'L' station and took the first train up to Forty-second Street. I like riding on the Elevated. When I got to Forty-second Street I walked straight over to Fifth Avenue and asked a policeman the nearest way to Christmas in New York. The policeman pointed over here and I came along up the steps past the flagstaff, and saw the window open so I slipped through the grating and walked in. Was anybody expecting me?"

"I was," said the Troll. "I knew you would be coming along so I left the window open for you."

"Very thoughtful of you, I'm sure," said Nicholas. "What do you do here on Christmas Eve?"

"I give a party," said the Brownie, "and invite everybody–Fairies, Giants, Trolls, Witches, Christmas Ghosts, Nixies, Pixies, Elves, Gnomes, Goblins, White Bears, Black Cats, Parrots. All the animals that talk or sing and all the people I like–Alice, Pinocchio, Hansel and Grethel, Sindbad and the rest. They're glad enough to get out of the books once a year I can tell you. The whole Brownie family takes a hand and we have lots of fun."

"Could I come to the party?" asked Nicholas.

"Glad to have you if you can be here on the stroke of midnight," said the Brownie. "But remember, when the clock in the Traffic Tower stops striking twelve all the windows and doors shut tight. No one can get in after that."

"I'll be on hand," said Nicholas. "May I look at the books to see who is coming to the party?"

"You may if you will be sure to put every one back just where you find it," said the Brownie. "I've given every one a number and they hate losing their places and getting lost on the night of a party."

"All right," said Nicholas, "I'll be careful," and he climbed down from the window seat and clattered away over the red tiled floor into the picture-book room where he found Peter Rabbit, Tom Thumb, Aladdin, Robinson Crusoe and other old friends, waiting for the Christmas Party to begin.

Nicholas had just taken out his little red leather book and was writing down the names of some books he had never seen before–"Perez the Mouse," "The Magic Fishbone," and "The Short History of Discovery," when the Brownie called out:

"I'm nearly starved! Come along Nicholas. Let's go over to Lucky's for a Christmas bite."

Rummaging through one of the drawers of the desk she drew forth a long red candle, lighted it, and handing the candle to Nicholas, the Brownie ran out of the Children's Room by the Forty-second Street entrance and disappeared in Bryant Park.

CHAPTER II

AT LUCKY'S

BRYANT PARK lay deep in snow behind the Library. It was silent and deserted, and for a moment Nicholas stood holding the red candle not knowing which way to turn to go to Lucky's. Then he heard. voice calling:

"Nicholas, Nicholas, run, I pray,

Thrice round the Fountain;

And when I say

Cross over, cross over, cross over, criss,

The way to Lucky's you cannot miss."

Nicholas ran three times around the Fountain and the third time round, the Brownie, who had been hiding under the canopy of William Cullen Bryant's statue, jumped down crying: "Come along Nicholas or we shall be too late. Lucky goes home early on Christmas Eve."

Just then Nicholas heard a rumbling sound he had heard before and looking up through the frosty trees he saw the train he had taken up from Bowling Green running rapidly back down town with a light in every window.

"I like Bryant Park with the Elevated running by," said Nicholas.

"So do I," exclaimed the Brownie. "I love it better than any place on Manhattan Island. I've lived here a long, long time, Nicholas. Before there was a Library here there was a big Reservoir with ivy growing over its walls. It was beautiful in October when the ivy leaves turned red. I always gave a party then–an out-of-doors party at sunrise, for at sunrise, Fifth Avenue is cleared for dancing all the way from Central Park to Washington Square."

"Why not give a party on the roof of the Library," asked Nicholas, "and invite the oldest fairies in the city up there to look around?"

"A fine idea," shouted the Brownie. "I could invite the fairies from Bowling Green, the Bowery, Gramercy Park, and Van Cortlandt Park. Oh, Nicholas, I'm glad you've come to New York. Shall you stay long?"

"That depends," said Nicholas.

"Do be careful crossing Fortieth Street," cautioned the Brownie, "it is getting almost as crowded as Forty-second Street and there's no policeman."

Forty seconds after Nicholas and the Brownie stepped out of Bryant Park they were walking down a long passage-way with steps at the bottom, leading straight to Lucky's Christmas fire. There was a flower-shop on one side of the passage-way and a hat-shop on the other. There was always room enough in the hat-shop to hold the hats at any season, but the flower-shop was much too small at Christmas. Then the passage-way was lined with Christmas trees standing straight against the wall and there were orange trees with little oranges growing on them, pots of white heather, primroses, cyclamens and Jerusalem cherries making. garden path of the way to Lucky's.

"Lucky would like it to be this way all the time," confided the Brownie as they scampered along. "Lucky likes gardens best of all."

They could hear people talking and laughing and the clinking of silver teaspoons and glass goblets and, as they passed the last of the Christmas trees, Nicholas could smell the delicious fragrance of Maryland chicken and Christmas cakes just out of the oven.

Nicholas felt a little strange and far away as he stood at the top of the steps leading down into that cheerful room filled with people who seemed to feel so much at home there.

There were branches of red berries on the tables and holly wreaths in the windows. There were shining copper and brass candlesticks and jars, pewter mugs and plates and porringers on chimney piece and dresser, and the firelight shining on these things made Nicholas think of home. He looked at his candle. It had gone out. Nicholas untied his muffler and stood quite still for a moment.

"Do you suppose Lucky will let me light my candle at her fire, Brownie?" he asked.

"Of course she will, there comes Lucky now," whispered the Brownie. "Did you ever see such a Christmasy looking lady?"

And Lucky, who was actually even more Christmasy than she appeared to be, looked down just as Nicholas looked up.

"Oh, you darlings," she exclaimed, speaking in a tone so low that no one else could hear her. "I was sure you would be coming, Brownie. Your Christmas bite is all ready the same as always. I've just seen the cook about it. I've invited two of my friends this year for I knew some one else was coming. I think I know his name. How do you do, Nicholas?" and Lucky took Nicholas's hand and shook it so cordially that the last feeling of strangeness left him.

"I'm well," said Nicholas. "But how did you know me, Lucky? I had to tell Brownie who I was."

Lucky laughed one of her merriest laughs.

"It's a secret from everyone else, but if you really want to know, Nicholas, I had it from a fairy who was hidden away in one of the bulbs I got for my garden last Christmas time. Those tulip bulbs come over from Holland every year and I always watch for a fairy to give me the news.

"Last Spring I listened and I heard very plain: 'On St. Nicholas Day (December 6th) a boy called Nicholas will leave Holland and go forth through France and Belgium to America. Watch for him on Christmas Eve and make him welcome.' So you see, Nicholas, I've been expecting you ever since tulip time."

"I'm glad I came," said Nicholas.

"I'm starving, Lucky, starving," murmured the Brownie.

"So are Ann Caraway and John Moon," said Lucky, and in no time at all she had piloted the Brownie and Nicholas across the room to the table nearest the fire. Two people were sitting there looking very happy.

"I have a little surprise for you," said Lucky to Ann Caraway. "Shut your eyes tight and don't open them until I give the word."

So John Moon, who was a boy about twenty-one years old, and Ann Caraway, who was a lady of no particular age, shut their eyes tight and when Lucky called "Open" they saw by the light of a tall red candle, which stood in the middle of their table, a strange boy about eight inches high, accompanied by a Brownie.

"Oh, Nicholas," Ann Caraway said, shaking the hand he stretched out to her, "I knew you would come this Christmas Eve. I've been telling John that something wonderful, mysterious, and entirely different from every other Christmas was sure to happen and here you are at last. I suppose you left Holland on St. Nicholas Day, didn't you?"

"Yes, I did, but how could you know that, Ann Caraway?"

"I felt it in my bones," said Ann Caraway, and then her eyes danced so merrily that John Moon and Nicholas burst out laughing, and they laughed so heartily there was no stopping them until Bessy appeared with smoking hot little chicken pies, toasted cheese muffins, guava jelly, mince pie, and some special dainties sent up by the cook for the starving Brownie.

"Dear old Brownie," whispered John after they had all been eating in silence for some time. "I've often seen you in Bryant Park but how did you find out the way to Lucky's?"

"O'Brien told me one night as he was closing the gate to the Library Court. Lucky had brought him a great bunch of flowers from her garden that day. O'Brien loves flowers. I've come often since then and I know the way upstairs to that little ball-room, with the crystal chandeliers, and the balcony where you sit and eat cherry pie and tell secrets to Ann Caraway in Springtime. I like that little ball room."

"So do I," said John Moon.

When they had all eaten as much as they could John Moon took out his pipe and lit it, and as he smoked and talked, and talked and smoked, he leaned over and touched Nicholas's helmet very gently, saying, "Where did you find it, old chap?"

"On the Chemin des Dames," said Nicholas and turned his head away for a moment. Then he said, "John Moon, I want to do something for those children whose homes were destroyed in the War, and I put on this helmet so that I shouldn't forget about it."

"I understand," said John Moon. "I don't want to forget either. I came out of college in my freshman year because I wanted to do something. I drove TM (trench munitions) over the same road you took to the Chemin des Dames."

"And I understand, too, Nicholas," said Ann Caraway, "although I have never been in France except in my dreams. Perhaps I can help you find some way to do the things you want done over there. Will you stay here and tell me just what you think the French children would like to have us do?"

"I will stay on one condition, Ann Caraway."

"And what is the condition?" asked John Moon.

"That I'm free to go and come when I feel like it and not fussed over."

"I think you will want to go where Ann Caraway goes," said John Moon, "for fear of missing something. She makes things happen any time, not just at Christmas."

"I'll promise, Nicholas, you shan't be bothered by anybody and that you shall never go where you don't want to go," said Ann Caraway. "I'm on my way now to hear the Carols at Trinity. Would you two boys like to walk down Fifth Avenue with me?"

"We'd love it," shouted John Moon.

"Shall I give the red candle to Lucky?" asked Nicholas, and the Brownie called out:

"Oh yes, and be sure, Ann Caraway, to get her a branch of your pine and a Christmas rose to take home tonight, and another one, please, for O'Brien at the Library Gate, for I haven't time. I promised the cook to clear up Lucky's kitchen and then I have to get ready for the party." Away scampered the Brownie down the back stairs, and with a Merry Christmas to Lucky, away walked Nicholas, Ann Caraway, and John Moon past the Christmas trees and the door of the flower-shop and up Fortieth Street to Fifth Avenue.

"Shall we cross over?" asked John Moon.

"I'd like to," said Nicholas. "I want to look in the shop windows."

CHAPTER III

DOWN FIFTH AVENUE

"THE loveliest window I know is in a flower-shop opposite the Library," said Ann Caraway. "I see a new flower every time I look in, and Nicholas, one of the oldest fairies on Murray Hill lives under that big lacy fern. We will go there for our Christmas roses."

"What color shall we choose for O'Brien?" she asked as they entered the shop.

"A pink one for Lucky and a red one for O'Brien," said Nicholas, "and be sure, Ann Caraway, that they smell like roses. I like the smell of a red rose best."

John Moon offered to take the roses back across Fifth Avenue if Nicholas and Ann Caraway would choose a present for him in one of the windows of the Favorite. They were not to buy it until he came back, he said, as he might not like their choice of a present.

But there were so many other people looking for presents in every single one of the ten windows of the Favorite that Nicholas and Ann Caraway could see nothing at all so they waited for John Moon at the corner of Fortieth Street.

"Why not step across and look in a Mirror?” called John Moon as he stood on the opposite corner on his way back from Lucky's.

Ann Caraway shook her head and John Moon crossed over.

"It would be silly to stop to look at ourselves in a mirror on Christmas Eve," said Nicholas, who supposed John Moon meant a looking-glass. John Moon laughed and Ann Caraway suggested waiting until after the Carols to visit the Favorite and the Mirror.

"The streets and shops will be less crowded then," said she, "and we can buy presents for other people as well as for you, John Moon."

"Are all the people in the world spending Christmas in New York?" asked Nicholas, as they stood on the crest of Murray Hill while hundreds of men, women, and children carrying parcels of every color, shape, and size streamed past them.

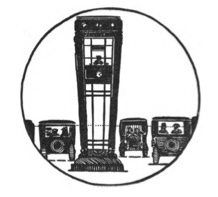

High above Fifth Avenue at Forty-second Street rises the Traffic Tower and in it, like a captain on the bridge of his ship, stands the new traffic policeman–the Policeman of the Signal Lights. When he flashes an orange light, long lines of shiny motor cars and taxicabs–black, orange, yellow, blue, brown, red, green, gray, black-and-white, brown-and-white, and checkered come running north and south–down the avenue on one side–up the avenue on the other side for two minutes.

When he flashes a red light everything stops, north and south, east and west.

When he flashes a green light, two great armies of motor trucks and cars rush out from the side streets and run east and west for two minutes. At the same signal all the people walking on Fifth Avenue who want to cross the street, cross over.

"That is the finest set of flash lights I've ever seen!" exclaimed Nicholas. "I wish I could see how they are worked from inside, but I suppose no one ever climbs the ladder of the Traffic Tower except the Policeman of the Signal Lights."

"No," said Ann Caraway. "The Policeman of the Signal Lights looks out of every one of the windows in his little tower–north, south, east and west. There's no room for anybody else up there."

"Let's move on with the crowd," suggested John Moon, stepping back from the curb where they had been standing to watch the signal lights.

"I've marched to music often," said Nicholas, "but I never marched to lights before."

"Where do all the people come from and where are they going, Ann Caraway?" he asked, as they walked on down Fifth Avenue.

"I often wonder," said she. "I like to think of them as Christmas Folk come from far and near on Christmas Eve to walk or ride over the most beautiful street of the City just because they love to do it. All the great parades march up or down Fifth Avenue, Nicholas, but the greatest processions of all are like the one we have just joined."

"Fifth Avenue is the street our soldiers marched down on their way to France, and it became a street of the World when it was hung with the flags of the Allies in 1918. Everybody came out to walk on 'the Avenue of the Allies,' and one night all the motor cars and green buses were sent up Madison Avenue and the people of New York danced on Fifth Avenue, right in the middle of the street. It was a wonderful time."

"Why, there's the Waldorf!" exclaimed Nicholas.

"Who on earth told you where to find the Waldorf, Nicholas?" asked John Moon.

"Nobody. I've seen pictures of it and the Waldorf is marked on my map as the house where the King and Queen of Belgium stayed. King Albert was always slipping out incog at night to see the city from an airship, the Woolworth Tower, or, on his own feet, and I intend to do the same thing from wherever I stay."

"The Prince of Wales stayed at the Waldorf, too," said John Moon, "and so did Li Hung Chang."

"There's one man at the Waldorf I should like to meet," said Nicholas. "His name is Oscar and he is a wonderful chef who knows just what to give all the famous visitors for breakfast, dinner, and supper. Do you know Oscar, Ann Caraway?"

"I've never had the pleasure of meeting him, Nicholas," replied Ann Caraway, "but I've often seen his picture lighting the candles on a birthday cake and I have visited his kitchens. Kitchens are much more fun to see than big empty ball rooms and bed rooms. There is always something cheerful going on in a kitchen, but cooks are not very fond of having visitors."

"If Brownie would invite me to go with her I'm sure it would be all right," said Nicholas. "She probably knows the Waldorf cook. I'll ask her."

"BIRDS and DOGS," shouted Nicholas in big gold letters, above the noise of the traffic at Thirty-first Street. "I must have a look in the window of that shop! I can't wait to see what kind of birds and dogs they keep here on Fifth Avenue."

"I'll cross over with you, Nicholas," said John Moon, "if you will cross right back again with me and have a look at the sail boats in my old toy-shop window."

"Pick me up at Brentano's in exactly five flashes," exclaimed Ann Caraway. "I've thought of a present Nicholas must have on Christmas Eve," and away she sped down Fifth Avenue leaving John Moon and Nicholas to cross over to look in the window of BIRDS and DOGS and cross back again on the next flash from the Traffic Tower to look in the toy-shop window.

When they came to Twenty-seventh Street Nicholas said, "Isn't Brentano's the shop where you can buy books in all languages?"

"It certainly is," said John Moon, "but how came you to know about it, Nicholas?"

"The Captain told me. He goes there often to buy books for his cabin–books in all languages. He said I would find wonderful picture books there–picture books from all over the world."

There was no time for even a peep inside the big book-shop for Ann Caraway came hurrying out with a small flat parcel which she gave to John Moon to put in his pocket.

Out into Madison Square they moved with the great stream of Christmas Folk. The snow was still falling and the lights in the windows of the tall Flatiron building straight ahead of them glittered like hundreds of stars.

"All the winds and the mists gather about the Flatiron," said Ann Caraway, "and sometimes the great building itself looks like a ship moving up Fifth Avenue."

"Step back across the Square for a moment, Nicholas," said John Moon, "and take a good look at Diana on the tower of Madison Square Garden."

"If the Circus comes to Madison Square Garden," said Nicholas, "it must be a bigger building than it looks from here to hold all the animals."

No sooner did Nicholas set foot in Madison Square than a bird-like voice rang out from the Christmas Tree:

"I'm lonely down here in Madison Square,

I'm the last fairy left, does nobody care?"

"Of course somebody always cares," said Nicholas, "specially on Christmas Eve. But why do you stay here if you feel the way you sound? Why didn't you move away when the others did?"

"I stayed for three reasons," replied the Madison Square Fairy. "First, because I love Diana. Second, to keep Admiral Farragut company. He has nothing else except his field glasses and with all the high buildings in front of him he can't see very far. Third, I stayed hoping to gather enough fairy light for the Christmas Tree. You see Nicholas they use too much electricity. There is nothing magical about so many red and green electric bulbs. Diana says it looks more like a rocket than a Christmas Tree."

Just then the chimes rang out from the Metropolitan Tower and at the flash of its red beacon light, the Madison Square Fairy flew out from the Christmas Tree and perched on Admiral Farragut's shoulder, singing:

"I'm gay as a lark in old Madison Square,

Since Nicholas looked on my Admiral fair."

"I'll come to see the Admiral often," said Nicholas. "I like him very much."

"We must take a car down Broadway now," said Ann Caraway, "or we shall be late for the Carols!" As they stood waiting for the car where Broadway and Fifth Avenue come together, Nicholas suddenly called out, "What is that funny looking thing running along so close to the ground? It looks like a big green caterpillar."

"That is our Broadway car, Nicholas, and it opens by magic," said John Moon. Sure enough, before the car stopped, the doors flew open on one side and when Nicholas stepped in he saw the conductor sitting high up in the middle of the car in a little ticket office on stilts. John Moon dropped some nickels into the box and Ann Caraway found a vacant seat in the front end of the car, which looked just as queer inside as it did outside, the two ends being much higher than the middle.

"This kind of a car was invented for ladies who wore hobble skirts to hobble into," said John Moon to Nicholas, as they stumbled in after Ann Caraway.

The green caterpillar crawled rapidly down past Union Square, Grace Church, and City Hall Park, and when the doors flew open at the gate of Trinity Churchyard ever so many children got out and quickly disappeared through one of the side doors of the church. The central doors were closed. Ann Caraway was about to follow the children into the church when Nicholas called to her, "Please wait a minute, Ann Caraway. I like to stand outside and listen to the chimes and I think I've seen this place before. I want to make sure."

Just then Nicholas heard the same rumbling sound he had heard up in Bryant Park and looking across the snow-covered churchyard he saw an elevated railway train stealing down behind the old brown church.

"Oh, now I remember. I rode past here on my way uptown and there is an 'L,' station at the back, the first stop after Battery Place."

"Old Trinity is nearly as old as the city, Nicholas," said Ann Caraway, "and it belongs to every one who loves New York. Before the tall buildings shot up so high Trinity spire could be seen for miles and its bells and chimes could be heard over on Long Island and far down the Bay."

"I'm ready to go in now," said Nicholas, and Ann Caraway led the way by the side door the children had entered.

"There is something mysterious about those front doors," thought Nicholas, as he crossed the threshold and discovered that the corresponding inside doors were closed also, and he said to himself, "I wonder what they do here on Christmas Eve."

CHAPTER IV

AT OLD TRINITY

TRINITY CHURCH was full of children when Nicholas came in with his two friends.

"We are just in time," whispered Ann Caraway as they slipped into the only vacant seats near the mysterious doorway.

As Nicholas turned to look again at the closed doors he saw above them, all along the organ loft, not one, but many flags–the flags of other countries.

"I like to see the flags here," he whispered to Ann Caraway. Then, as he sat quite still, smelling the fragrant pine and watching the candles burn above the roses on the altar–far, far away he heard boys' voices singing:

"It came upon the midnight clear

That glorious song of old."

A door to the left of the chancel opened and out streamed the choir.

All over the church the children rose up, looking as if they were starting out on a wonderful journey. Down one side aisle came the choir and up another, circling the church, still singing:

"Look now, for glad and golden hours

Come swiftly on the wing."

"The Bishop of New York is walking at the end of the procession," Ann Caraway whispered to Nicholas, as the choir and the clergy were taking their places in the chancel.

There was a short service and then the Bishop, instead of mounting the high stairway into the pulpit, came and stood at the lower edge of the chancel, as near to the children as possible. Very clearly and beautifully he told the story of the first Christmas Eve and invited everybody sitting there in Trinity Church to go on a pilgrimage to Bethlehem.

As the Bishop spoke the last words of his invitation, the mysterious doors opened, and deep in the old doorway there stood a manger with the figures of the Christ Child and the Virgin Mary, the Shepherds with their sheep, and the Wise Men with their gifts.

At the call of trumpets the choir boys rose and, led by the trumpeters, they came down the central aisle to the mysterious doorway singing, "Noël, Noël."

Behind the choir came the clergy and the Bishop, then came the children–hundreds of children from all over the city–and the mothers and fathers and friends who had come with them walked beside them.

Everyone paused before the manger, then up the right-hand aisle moved the long procession singing, "Good King Wencelas." Through mysterious rooms behind the altar the children followed choir and clergy singing one old carol after another.

Down the left-hand aisle they came until at last every one had passed by the manger. As Nicholas and Ann Caraway slipped back into their seats the choir boys were singing:

"Oh, little town of Bethlehem

How still we see thee lie

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by."

"What a beautiful carol," exclaimed Nicholas as it ended, "I've never heard it before."

"It is an American carol, Nicholas," said Ann Caraway. "The words were written by a man everyone loved who became a bishop and whenever I hear them sung down here, where the great city of New York began as a little town, it seems to me no larger than the little village where I was born and first heard about him.

"An aunt of Phillips Brooks lived just across the street from my old home–a charming old lady who was the grandmother of one of my playmates."

"'I rocked Phillips in his cradle,' she would often say and she would tell things about him as a baby, a boy, and a man with nieces and nephews of his own–things which made him seem so real that I grew up thinking of Phillips Brooks as one who understood children and Christmas better than anyone else in the world."

"Did you ever see him, Ann Caraway?"

"Yes, twice, in his own Trinity Church in Boston. He was more wonderful than I know how to tell you. I always like to think of him here for he often came to Old Trinity to preach."

"Will you tell me about the big white flag with the blue and the gold stars?" Nicholas asked as they rose to leave the church.

"It is Trinity's Service Flag, Nicholas. There is a blue star for every one of the hundreds of men who served in the War and the gold stars are for the men who gave their lives."

"The church was often filled with soldiers in war time. I remember a Sunday when troops of Anzacs came to a service here on their way to France from their distant homes in Australia and New Zealand. The Bishop, who was not a bishop then but the rector of Trinity Church, welcomed the soldiers just as he welcomed the children today."

John Moon had become separated from Nicholas and Ann Caraway during the procession and he now joined them as they stood once more before the manger.

As they turned to go out from the church by the side door they met the Bishop wishing everybody a happy Christmas and looking as if the wish had already come true for himself.

"Please thank him for me, Ann Caraway," said Nicholas. "Tell him I shall come here whenever I am in New York on Christmas Eve."

Now Ann Caraway had never spoken to the Bishop before, but she couldn't well refuse to give a message from Nicholas, and the moment she began to speak he became a friend on the street of her own little town.

"I look forward to this Christmas Eve visit to Bethlehem all through the year, quite as eagerly as the children do," said the Bishop. "That must be why it seems so real," thought Nicholas.

CHAPTER V

BOWLING GREEN AND THE BATTERY

"LET'S keep on down to Bowling Green and look for St. Nicholas where Oloffe the Dreamer saw him," said John Moon with a beaming smile, and they passed through the gates of Old Trinity and turned down Broadway.

"Who was Oloffe the Dreamer?" asked Nicholas. "Will you tell me about him, John Moon?"

"Oloffe was a countryman of yours, Nicholas, of that famous race of Knickerbockers Washington Irving tells about. His real name was Oloffe Van Kortlandt and he longed for lands of his own for he had possessed none in the old world. Oloffe had an amazing talent for dreaming and for making his dreams come true. Irving says he was the first great land speculator in these parts."

The sun had gone down but sunset lights were still in the sky and a fresh wind was blowing up from the harbor. Lower Broadway was deserted at that hour and as he walked along listening to John Moon's story of Oloffe the Dreamer, it seemed to Nicholas that he could see that old Dutch ship–the Goede Vrouw with the image of St. Nicholas at her bow–sail slowly out from the harbor of Amsterdam in Holland over the same sea he had just crossed, through the Narrows, and up the Bay to the exact spot where he had landed that very Christmas Eve.

"Your countrymen landed in New Jersey first," John Moon was saying. "They were planning to build a great Dutch city over in Pavonia, as New Jersey was then called, but Oloffe told them that St. Nicholas had appeared to him in a dream the night before and told him to look for a better site for the new city. They were all very much impressed by Oloffe's dream and an expedition was at once fitted out to explore the coast. Oloffe was commodore of this voyage and he set forth in the jolly-boat of the Goede Vrouw with a squadron of three canoes.

"As they were coasting along past Governor's Island, a school of jolly Porpoises came rolling and tumbling by. Oloffe hailed the Porpoises with joy for he looked upon the appearance of these round, fat fish–burgomasters among fishes, he called them–as a happy omen of the success of the undertaking and directed his squadron to steer in their track.

"The Porpoises gave them a lively voyage up East River, where the rapid current seized the tub of a jolly-boat, whirled it about and hurried it forward with such velocity that Oloffe believed they were in the hands of some supernatural power and that the Porpoises were towing them to a fair haven where all their wishes and expectations would be realized.

"Borne on by the resistless current, they doubled the point of land we call Corlear's Hook and drifted into a sunny lake to which they gave the name of Kip's Bay in honor of the valiant Hendrick Kip at the bow of the jolly-boat. A sudden turning of the tide drove them to land at Bellevue, where they held a council-dinner, in the course of which the great family feud between the Tenbroecks and the Hardenbroecks broke out. Oloffe put an end to their lively and interesting dispute by deciding to explore still further in the track of the Porpoises.

"The tide having turned in their favor, they coasted along by Blackwell's Island, admiring the beauties of the fair island of Mana-hatta, with its great tulip-trees rising from forests of oak and chestnut and elm, until they came to a lovely woodland vista through which they looked toward Haarlem and Morrisania. The sun had gone down and they drifted quietly on in the purple haze of a Spring twilight until they were suddenly roused by the violent tossing of their boats. Great waves were boiling and foaming about them. Oloffe bawled aloud to put about, but his words were lost in the roaring of the waters. The winds howled, the waters raged and those infamous rocks, the Hen and Chickens, nearly sealed the fate of the heroes of Pavonia.

"But worse was yet to come. Into that tremendous whirlpool, the Pot, the jolly-boat was drawn and there whirled about until Commodore Van Kortlandt and his crew were completely overpowered by the horror of the scene and the strangeness of the revolution.

"When they came to their senses they found themselves stranded on the Long Island shore. Oloffe told many wonderful stories of his adventures in the Pot–how he saw spectres flying in the air and heard the yelling of hobgoblins and put his hand into the Pot when they were whirled about and found the water scalding hot, and beheld strange beings seated on rocks skimming it with ladles.

"Most of all he enjoyed telling that he saw the Porpoises, who had betrayed them into this peril–some broiling on the Gridiron and others hissing on the Frying-pan. Having made his escape from its terrors Oloffe naturally wished to give an appropriate name to this perfidious strait and he called it Helle-Gat (Hell-Gate). The Devil has been seen there, it is said, sitting astride of the Hog's Back playing on the fiddle or broiling fish before a storm.

"Oloffe and his remaining followers, for the squadron had been totally dispersed by the disaster, decided that it would never do to found a city in so diabolical a neighborhood. They made up their minds to roam no more and they steered their course back fully determined to build the Dutch city of their dreams in the marshy region of Pavonia where they had first landed. But just as they sighted the familiar shores of their own village of Communipaw, Commodore Van Kortlandt's tub was rolled high and dry on the point of an island which divided the bosom of the bay. Oloffe looked about and saw that the shore of this island abounded with oysters and he at once decided to celebrate his wonderful escape from Hell-Gate with a banquet.

"Invitations admitting of no refusal were dispatched to the oysters. A fire was made at the foot of a tree and all hands fell to roasting and broiling and stewing and frying and a sumptuous feast was soon set forth.

"Oloffe ate profoundly, and when he had finished he sank down upon the green turf and a deep sleep stole upon him.

"And the sage Oloffe dreamed a dream, and lo! the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children and he descended and lit his pipe by the fire and sat himself down and smoked, and as he smoked the smoke from his pipe rose into the air and spread like a cloud overhead. And Oloffe bethought him, and he hastened and climbed up to the top of one of the tallest trees, and saw that the smoke spread over a great extent of country; and as he considered it more attentively, he fancied that the great volume of smoke assumed a variety of marvellous forms–palaces, domes, and lofty towers appeared and then faded away until the whole cloud rolled off and nothing but the green woods were left.

St. Nicholas at Bowling Green

"And when St. Nicholas had smoked his pipe, he twisted it in his hatband and laying his finger beside his nose, gave the astonished Van Kortlandt a very significant look, then mounting his wagon he disappeared over the tree tops. And Van Kortlandt awoke from his sleep greatly instructed; and he roused his companions and related his dream, and interpreted it to be the will of St. Nicholas that they should settle down and build a city here and that the smoke of the pipe was a type of how vast would be the extent of the city.

"Having accomplished their purpose, the voyagers returned merrily to Communipaw where they were received with great rejoicings. A general meeting was called of all the wise men of Pavonia and when they had listened to the whole history of the voyage and to Oloffe's dream they began at once to prepare to move from the green shores of Pavonia to the pleasant island of Mana-hatta.

"The 'grand moving,' as it was called, took place upon May Day. And after they had bought Manhattan Island from the Indians and had built a fort and a trading-house and some houses to live in, your countrymen built a chapel to the good St. Nicholas on the spot where he had appeared to Oloffe the Dreamer–the very spot where we are now standing, Nicholas," said John Moon, for they had entered Bowling Green Park, and Nicholas was staring straight ahead at the Custom House.

"What a perfectly wonderful Christmas Story! John Moon," he exclaimed.

"And you told most of it in Irving's own words," said Ann Caraway. "You must have learned it by heart."

"I suppose I do know that story almost by heart," John Moon responded. "I never tried telling it before but I liked it so much the first time I fished it out of Knickerbocker that the words stuck along with the story."

"Was Washington Irving named for George Washington?" asked Nicholas.

"He really was, Nicholas," said John Moon. "When General Washington entered New York with his army there was a little baby in a house not far from old Trinity whose mother settled the question of his name by saying, 'Washington's work is ended and the child shall be named after him.'

"This boy was six years old when George Washington came back to New York as President of the United States. Thanks to the enterprise of Lizzie, a Scotch maid in the Irving household, little Washington was presented to his great namesake. Lizzie wasted no time in formalities but followed the President into a shop one morning and saluted him saying:

"'Please Your Honor,' pointing to the little boy, 'here's a bairn as was named after you.'

"And Washington placed his hand on Washington Irving's head and gave him his blessing."

"He must have been very proud of his name after that," said Nicholas.

"He was proud of it," John Moon replied, "but Washington Irving was too full of fun and mischief when he was a boy to tell how much he really cared. He became a famous traveller, Nicholas, and he began to travel as soon as he could walk. The Town Crier was always bringing him home from his explorations of Manhattan Island, and as he grew older he wandered further away–up the Hudson to the Catskill Mountains, or down to the piers to watch the ships."

"Shall we go and watch the ships ourselves," said Ann Caraway, "the lights are coming on all over the harbor now."

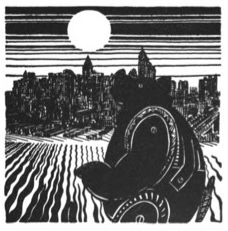

"Why, there's the funny Round House I ran around!" exclaimed Nicholas as they crossed Battery Park. "It looks like a fort from here."

"Our Government did build it for a fort," said John Moon, "but the fort wasn't needed very long so it was turned into a great pleasure palace called Castle Garden with a bridge leading out to it from the mainland. A famous party was given there in honor of Lafayette and years afterward Barnum brought Jenny Lind over from Sweden to sing in Castle Garden. People came from all over the country just to hear her sing and to walk on the Battery, which was the fashionable promenade in those days."

"Do they have parties in the Round House now?" asked Nicholas.

"Marvellous parties," John Moon replied. "Blue Angel Fishes, Red-Breasted Sunfishes, Telescope Gold-fishes and Rainbow Trout swim around in the boxes and balconies where people used to sit and listen to Jenny Lind, while Seals and Sea Lions, Alligators and Crocodiles, Turtles and Bull Frogs slip and slide and hop and glide over the old ball-room floor. All the fishes and sea animals live in the Round House now and we call their palace The Aquarium."

"Are there any Porpoises?" asked Nicholas.

"Sometimes,” replied John Moon, "but Porpoises are not very fond of living in a palace. They like to be on the move."

"Exploring the coast for Oloffe or signalling ships, I suppose," said Nicholas. "I saw lots of them coming over."

"The nicest time of all to visit the fishes," said Ann Caraway, "is when the sun is shining straight into their palace windows. Then you can watch the gayest ones of all slip into one lovely ball dress after another while the old Sea Lion mounts his platform and calls the dances from the ball-room floor. Beau Gregory of the Bermudas leads off with Queen Trigger in her royal purple and gold–then little Half Moon comes dancing along with her other half, both in exquisite silver blue, carrying the tiny ladders they brought with them from South America, and looking back over their shoulders to watch the Japanese Goldfish spreading fantails and fringe tails to the sound of sea music. Faster than you can count, Nicholas, they come to the ball–Blue Parrots and Rabbit Fish, Red Snappers and Spot Snappers with old Sergeant Major; Moonfish and Fool Fish, Puffers and Blowers with Cow Pilot as leader, Nurse Sharks and Surgeons and hundreds of others, and after them all ride the Sea Horses."

"I'm coming down to the Round House the first sunny day!" exclaimed Nicholas, and as they walked back across Battery Park, he said to himself, "I wonder what the Fishes do Christmas Eve."

CHAPTER VI

TO WASHINGTON SQUARE

THE moon was looking over the clock tower on the Jefferson Market Court House straight into Patchin Place when Ann Caraway walked in with the two boys.

"I love to stand under the old street lamp at the far end and pretend I'm in London," said she. "Wouldn't you both like to try it while I choose some Christmas wreaths at the little flower-shop on the corner?"

Over the unbroken snow of Patchin Place ran Nicholas in his wooden shoes, never stopping until he stood under the old gas lamp at the far end.

"I've never been in London, John Moon, but it does look like pictures I've seen," he said.

Ann Caraway was waiting for them at the door of the flower-shop under its painted sign of a basket of flowers. She had chosen a soft pine wreath with cones on it and two smaller ones of red partridge berries.

"There are lovely holly boughs outside the other little flower-shop. Please pick out some branches with lots of berries, John Moon," she said and vanished from sight.

"Where are you, Ann Caraway?" called Nicholas. No answer. "She didn't go into the flower-shop, John Moon. Where can she be?"

"Ann Caraway. Ann Caraway," he called again and this time he called louder for a Sixth Avenue elevated train was thundering by.

"Lift up the latch and walk in, Nicholas," a merry voice called back, and to his utter amazement Nicholas beheld a green wooden gate close beside the flower-shop. Lifting the latch very cautiously he stepped from the sidewalk into a snowy courtyard. It was dark and mysterious.

"If Hans Andersen had ever lived in New York, I'm sure he would have lived in Milligan Place," said Ann Caraway, who was standing under the old street lamp by the side wall watching the doorways of three old houses on the other side of the courtyard.

"The landlord fills that old urn with flowers for the Greenwich fairies every Spring," she said, "and I know that people live in the three old houses but whenever I look in here I see only the cats of Milligan Place."

Just then John Moon stepped through the green gate with an armful of holly boughs.

"Once upon a time"–he began.

"There isn't time for a story, John Moon," said Ann Caraway. "We've still all the presents to buy, remember."

"Let's begin at Ugobono's!"

In one of the two windows of Ugobono's pastry shop there was a wonderful thin cake watch, with a chocolate stem winder, pink and white dots for the minutes, and vanilla hands. Back of the watch was a heap of round loaves of pani toni with raisins and citron sticking out of their sides and burnt almonds on top, a fluted-icing basket of meringue mushrooms stood on one side, and a pan of marrons glacé in pink and white paper cases on the other. In the other window were the most fascinating tin boxes and glass bottles swinging from basket hangers. They quickly filled a box with almond cakes and macaroons, pani toni and marrons, and Nicholas bought a big tin box with twenty-four little packages of nougat inside, each with a different picture of Italy on the wrapper.

When they came out of Ugobono's they walked along Eighth Street looking into the windows of fruit-shops and markets with Christmas trees beside their doors, until they heard the carol singers singing to the artists who live in the old stables in MacDougall Alley.

Candles burned in the stable windows and through an open doorway a Christmas fire sent its light across the snow.

"Let's follow on out into Washington Square," suggested John Moon.

"Some of the people who kept their horses in the stables of MacDougall Alley still live in the beautiful old red houses on the North Side," said Ann Caraway, as they passed out into the great Square which lay white and glistening in the moonlight.

"It is a lovely place to live," said Nicholas. "I'd like to look inside one of the old houses some day."

The windows of the tall apartment houses to the east and west were lighted also and as the Christmas Waits sang north and south, windows were raised and doors stood hospitably open.

As the singers moved across the Square on their way to Greenwich Village, John Moon suddenly exclaimed, "Here's our very own bus, Nicholas, scramble up on top!"

With a hand to Ann Caraway, they mounted the stairway to the top of a green bus and rode up past Washington Arch with its lighted Christmas trees, past the old Brevoort with holly wreaths in all the windows and a gay company of Christmas guests streaming in and out of its wide white doorway.

"Where are we going now?" asked Nicholas.

And John Moon leaned across the holly boughs to whisper in his ear. "We are riding north on a St. Nicholas bus. Do you like little old New York, Nicholas?"

"I love it," said Nicholas.

CHAPTER VII

CHRISTMAS EVE IN CHELSEA

"WILL you ride down to the Night before Christmas Country in our orange taxi or must we leave you at the Pennsylvania Station?" said Ann Caraway to John Moon as they came out of the Favorite loaded down with presents.

"I'd love to come to Chelsea with Nicholas," John Moon replied, "but Mother is expecting me home early to spend Christmas Eve with her, so please drop me at the station."

When they walked into the Mirror before visiting the Favorite, Nicholas discovered that the Mirror wasn't a looking-glass at all but a big candy-shop with all sorts of surprise presents. John Moon handed him a package of chocolate cigarettes and when Ann Caraway said, "Choose something, Nicholas," he pointed to a glass jar filled with red and white striped bull's eyes.

"Now let's fill a big box for other people," said Ann Caraway. They had great fun choosing, first a layer of lollipops, next a layer of red and yellow barley sugar horses and elephants and camels, then a deep layer of sticks and stumps of red and white and pink Christmas candy; after that came gum drops, marshmallows, and striped peppermint sticks. On top there were ever so many little surprises–no two alike–with candy canes slipped in between, and in the crooks of the canes little round cakes of chocolate frosted with tiny white sugar beads, and last of all, heaps of red checkerberries.

The box had to be kept right side up, so after Ann Caraway had paid for it, receiving in exchange for her money a handful of little silver watches and fiddles, pipes, trumpets, and steamboats, they put it in an orange taxi while they shopped at the Favorite.

All the presents at the Favorite cost either five cents or ten cents and with a jingling bag of new dimes and nickels there was no waiting for change. In less than ten flashes they had bought fifty presents, with ten gaily decorated boxes to put them in, and piled them high on the floor of the orange taxi. There was just room to squeeze in themselves.

Down Fifth Avenue they rode on a flash of orange light from the Traffic Tower, and turning west by the Waldorf on a flash of green, they were soon coasting rapidly down the long runway of the Long Island side of the Pennsylvania Station.

As he leaped from the taxi to run for his train, John Moon drew from his pocket the parcel tied with red cord and tossing it into Ann Caraway's lap he called, "I've guessed what it is, Nicholas. 'Happy Christmas to all and to all a good-night!'" and waving a trumpet and a Scotch plaid notebook he raced past the eager Red Caps and disappeared inside the big station.

"I like John Moon," said Nicholas. "What does he do, Ann Caraway?"

"He writes news for a newspaper but sometimes a story or a poem steals into his mind and he writes it down in a book of his own. That's why he wanted a note-book for a present."

"There's the Post Office!" cried Nicholas as they turned south on Eighth Avenue. "Please go slow," he called to the driver and leaning out of the taxi window he saw letters and packages coming out of every one of the eleven front doors of the big Post Office.

"The nicest presents of all are the Christmas Letters from Everywhere," said Ann Caraway. "Read what it says across the front of the Post Office–just above the pillars:

NEITHER SNOW–NOR RAIN–NOR HEAT

NOR GLOOM OF NIGHT STAYS THESE

COURIERS FROM THE SWIFT

COMPLETION OF THEIR

APPOINTED ROUNDS

"I'd like to be a Postman," said Nicholas. "It sounds wonderful."

"We're coming to the Night before Christmas Country!" Ann Caraway exclaimed at Twenty-fourth Street. "Prepare for surprises, Nicholas. There's Lucky's town house, she lives in one of the old Chelsea cottages with an iron portico in front and a little garden behind, but her real garden, where the tulips bloom, is out in the country."

On Tenth Avenue they met the first surprise. A boy on horseback, waving a lantern and a red flag as he rode just ahead to clear the way for the locomotive of a long freight train. This was not the kind of a locomotive you see anywhere else. It was made to look like a funny little house in the days when horses were afraid of the old wood-burning kind of engine with its big spark-drum and cow-catcher.

"We call him the Paul Revere of Chelsea, but the New York Central Railroad calls him a 'dummy-boy," said Ann Caraway. "You will hear his trains go by at all hours of day or night, Nicholas, and you will hear all the big steamers that put in or sail out from Chelsea Docks and all the little tugs that screech alongside them, and the whistles and the foghorns blowing from the ferry-boats crossing North River on stormy nights and mornings."

"I'm glad I came here with you, Ann Caraway," said Nicholas as they rode up past London Terrace, a row of old houses with deep door yards in front and gardens at the back which look into the gardens of Chelsea cottages.

At the oldest fruit-shop in Chelsea they stopped for a basket of red apples which George Bernero assured Ann Caraway came from "Up-State."

"There's Joe Star at the window," cried Ann Caraway as the orange taxi drew up before one of the old red brick houses in West Twentieth Street.

"Merry Christmas, Joe!" she called. "We can't move for the presents!"

"I'm coming!" shouted Joe Star, and a moment later he had gathered up every single one of the presents and was climbing the stairs to the Christmas Room leaving Nicholas and Ann Caraway to follow on behind.

Joe Star had been so intent on the presents that he didn't even see Nicholas until he turned to greet Ann Caraway with a "Joyeux Noël, ma chère tante!"

"Oh, Joe," said Ann Caraway with laughing eyes. "Here's Nicholas come for Christmas. My nephew Joe Star from Maine, Nicholas."

"Joyeux Noël, Nicolas!" responded Joe Star, shaking hands so cordially that Nicholas felt entirely at home, untied his muffler, and ran over to the fireplace to warm his hands.

"This accounts for the mysterious hamper I found on the steps as I came in," said Joe Star. "It is marked:

MERRY CHRISTMAS TO NICHOLAS AND JOE STAR

from LUCKY

per order of BROWNIE.

I didn't venture to unpack the hamper until I knew who Nicholas was."

"Suppose you and Nicholas unpack it now while I slip into another dress," said Ann Caraway and she left the two boys alone in the Christmas Room.

It was a big square room with two windows overlooking Chelsea Square. There was a Christmas tree in one window and red candles burned on the old mahogany desk which stood in the other.

When Ann Caraway came back she was wearing a cherry-colored dress and black velvet slippers with sparkling buckles. Taking a wreath of partridge berries from the heap of presents Joe Star had piled up on the floor she placed it on a pewter plate under the pine boughs on the dresser.

"A bit of the Maine woods, Nicholas," she called gaily and then she spied the little supper table in front of the fire.

"I've been saying, 'Little table appear,' all the time I've been dressing," she cried, "and here it is with quite the most delectable Christmas Eve supper I've ever seen." And seating herself in the big wicker chair Joe Star had placed for her, Ann Caraway took a second look at the wishing-table and she saw a plump little roast duck, a mould of red currant jelly, olives, bacon and celery sandwiches cut in three-cornered shapes, thimble biscuits, light as feathers, and a round Dutch cheese marked N. with hard toasted crackers beside it.

On the dresser were some very special Christmas cakes marked N., A. C., J. M., T. and B., a mince pie marked J. S., and two gingerbread boys.

"We unpacked only one layer of the hamper," said Joe Star. "Then we came to a big sign:

GO NO FURTHER, SAVE FOR BREAKFAST CHRISTMAS MORNING."

"I don't see what else there can be," sighed Ann Caraway."There's everything and more here."

"But you must both be hungry. Let's begin!"

"I'm nearly always hungry," said Nicholas as Joe Star began to carve the duck.

It was a merry little supper round that wishing-table for Joe Star cracked jokes and told funny stories, sometimes in English, sometimes in French, not that he knew the language very well but he liked to use all the French he knew.

"What do you do, Joe Star?" asked Nicholas.

"I go up to the moon in a large balloon, Nicholas, old boy. I take a hop whenever I can but I'm out of the Navy now looking for Captain Kidd's treasure here in New York."

"I can show you just where Captain Kidd used to live," cried Nicholas. "It is marked on my map. Can I help you look for treasure, Joe Star?"

"You certainly can, Nicholas, old boy. We'll have a high old time treasure-hunting up and down Wall Street and Maiden Lane, although they do say Gardiner's Island is the place to search."

When they had all eaten as much as they could, the wishing-table disappeared, and as they sat talking before the fire Ann Caraway suddenly remembered Nicholas's present and gave it to him.

Untying the red cord, Nicholas drew from its wrapping a flat red book with, "A Visit from St. Nicholas" printed on the cover.

"It's a jolly book," said he. "You read it to us, Ann Caraway."

"Yes, do read it," urged Joe Star and settled himself down in a big armchair before the fire. "I haven't heard it for almost a year."

So Ann Caraway began to read:

"'Twas the night before Christmas

When all through the house

Not a creature was stirring

Not even a mouse.

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds

While visions of sugar-plums danced through their heads,

And Mama in her kerchief and I in my cap

Had just settled our brains for a long winter's nap–"

Ann Caraway stopped short, and she and Nicholas watched Joe Star, open-mouthed. He was squatting on the hearth balancing a live coal over the bowl of his pipe and drawing at it furiously. Puffing clouds of smoke, Joe Star tossed the coal back into the fire and walked over to the window.

Ann Caraway read on:

"When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter

I sprang from my bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash...."

The window rattled. Nicholas and Ann Caraway turned in their chairs. Joe Star was hanging out of the window.

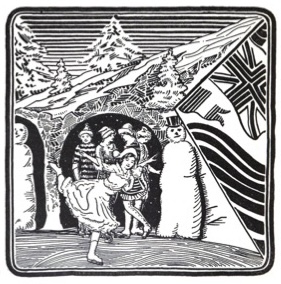

"Nicholas!" he called softly, "Nicholas, old boy!"

Nicholas ran over to the window.

"The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow

Gave a lustre of midday to objects below."

"On such a night a hundred years ago," continued Joe Star, "St. Nicholas came to Chelsea. It was a countryman of yours, Nicholas, a ruddy-faced Dutchman who lived on the old place who gave Clement Moore the high sign. And Clement Moore, I'm dead certain, deserted his library, left that remarkable Hebrew dictionary of his–he made the first one–and all his Oriental books and took a walk around his grandfather's Chelsea farm with the Dutchman, who told him everything he knew about St. Nicholas. There were no rows of houses in Chelsea then. It was like the open country and they could walk all over the place from Eighth Avenue to the river and cross lots from Nineteenth Street to Twenty-fourth Street.

"You see the church tower over in Chelsea Square, Nicholas. Just beyond it on a hill, facing the river, stood the old three-storied stone house where Clement Moore was born. It had a cupola and wide chimneys on top and on this side of it was a broad porch with a roof, shaded by a tall tree, most conveniently placed for climbing in and out of windows."

Nicholas chuckled and gave Joe Star a poke in the ribs.

"There was another porch in front of the house with a high flight of steps leading up to it, where the children used to sit and watch the boats on the river, but Clement Moore came back to the side porch after his walk with the Dutchman, you may be sure, and stood there in the moonlight looking across the fields and orchards he had already begun to give away.

"Then he lifted the latch very cautiously and went in, put on his cap, and sat down by the fire to watch for St. Nicholas.

"Your little red book tells the story of St. Nicholas's visit just as Clement Moore wrote it down as a present for his own little girls that Christmas Eve, never dreaming that he was writing our American Christmas poem. The children liked their father's present so much that they showed it to some of the many visitors who were always coming to stay at Chelsea. One of them copied it into her album and when she went home (she lived in Troy, New York) gave it to the editor of the Troy Sentinel, who published it with an old woodcut of St. Nicholas the very next Christmas (December 23, 1823).

"Other newspapers copied it and the boys and girls all over the country soon knew the poem by heart and have been repeating it on Christmas Eve ever since.

"How's that for a true story, Nicholas?"

"It's a good one, Joe Star. Tell me some more about that old house on the hill. What was it like inside?"

"I was never inside, Nicholas, old boy. The old house and the hill where it stood disappeared years ago [1853]. I saw a picture of it hanging in the real estate office round the corner. It reminded me of another old grey house on a hill in Portland, Maine, the house where I was born. It has a cupola, too, and it looks across an arm of Portland harbor to Cape Elizabeth. My grandfather was always walking about his old place.

"Clement Moore's grandfather–Captain Thomas Clarke, had a long record of hard fighting in the French and Indian Wars. When he was retired he decided to spend his old age in America, so he bought this tract of land three miles from City Hall and called it Chelsea after the old hospital near London.

"His house was burned over his head in his last illness and Clement Moore's grandmother, Mistress Molly Clarke, built the house St. Nicholas visited and lived in it for many years. When she died she willed it to her son-in-law Bishop Benjamin Moore who was Clement Moore's father."

"Clement Moore's father was the second Bishop of New York and a rector of Old Trinity," said Ann Caraway coming over to the window. "There was no school for bishops and clergymen in this country in his time so Clement Moore gave one of his fields and an orchard and helped build one. There it stands out in Chelsea Square. Up the street a little way there is an old grey stone church with a high tower which he also helped to build after first giving the land."

"Is it named for St. Nicholas?" asked Nicholas.

"No, for St. Peter. No one dreamed in the days when the church was built that this part of New York would ever be called, 'the Night before Christmas Country.'"

Joe Star drew in his head. "I haven't heard a single carol," he said with a sigh. "Is it too late?"

"We will be just in time to hear the Carols sung at Calvary Church if we start right off," said Ann Caraway. "The church is lighted only with candles and it is very lovely at this hour. We'll walk round the corner and see the moon over Gramercy Park afterward. Would you like to go, Nicholas?"

"No, thank you, I'm sleepy," said Nicholas. "I'll stay by the fire."

"You'd better turn in, Nicholas, old boy," said Joe Star. "I'll take the next watch."

Nicholas hopped into bed and before the street door closed behind Ann Caraway and Joe Star he was fast asleep.

CHAPTER VIII

ST. NICHOLAS COMES

THE hands on the clock of the Traffic Tower were pointing toward midnight when through the wide open windows of the Christmas Room came the first faint sound of jingling bells–nearer and nearer came the bells and then on the roof, the clatter of reindeers' hoofs and the calls of their driver.

Nicholas opened his eyes and there on the hearth stood a jolly old man, dressed all in fur, holding out a little fur coat and a scarlet cap.

"Quick, Nicholas, it's close upon midnight!"

In a twinkling Nicholas was inside the little coat and drawing the scarlet cap down over his helmet, he sprang up the chimney after St. Nicholas and into the waiting sleigh.

A word to the reindeer and away they flew–high over the snowy roofs above the fields and orchards of old Chelsea.

Far down North River they could see the lights of the ferry-boats crossing back and forth to the Jersey shore and tall ships rose in the moonlight beyond the Bay.

"I came by the harbor way," said St. Nicholas, "up over the Bowling Green and dear old Greenwich to Chelsea, and at midnight I always drive over the Bowery where my good friend Peter Stuyvesant rests."

In another second they were above St. Marks and Tompkins Square.

Far down East River they could see the twinkling lights of Brooklyn Bridge and Long Island, a fairyland under the stars.

The sleigh swerved in a zigzag and another sharp turn sent them flying north again. Faster and faster they flew over Stuyvesant Square, over Irving Place, and Gramercy Park.

"There's Diana," called Nicholas. "Merry Christmas, Diana!" he shouted as they passed, and Diana, standing on tiptoe, watched them fly up over Madison Avenue.

A little white marble palace shimmered in the moonlight as they looked down into a lovely garden sparkling with frost and snow. Then higher than they were riding, just above the reindeers' horns, rose a wonderful tower and the next instant the reindeers' hoofs struck the roof of a great marble palace and down one of its chimneys sprang St. Nicholas with the boy from Holland.

The fire had burned down to coals in the deep fireplace of a very beautiful room and beside it, in a comfortable armchair, sat an old man fast asleep.

"I wake him up every year," whispered St. Nicholas, "and this year I'm waking his children, for when I leave Haarlem I drive out over the Hudson River and straight on past the Kaatskill Mountains. Watch closely as I go, Nicholas, and when you hear the sound of a trumpet lead him over to the window before he sleeps again." And laying his finger aside of his nose, St. Nicholas gave a nod and vanished up the chimney.

The only light in the big room came from the moon streaming in through windows from which the soft blue velvet curtains had been drawn back, yet Nicholas could see quite clearly the face of the old man sitting there and it seemed to him one of the kindest and merriest he had ever looked upon.

As the reindeer raced off over the roof above his head, the old man woke with a start.

"There goes old St. Nicholas and I've missed him again. But, bless my soul, who are you!" he exclaimed. "The Old Fellow leaves me something every year but never a boy like you before. Who are you?"

"Don't you know me, Sir? I'm Nicholas. And you are, you are–I know you are–Washington Irving."

"To be sure I am, Nicholas, but how did you recognize me?"

"John Moon told me, Sir, just how you look. John Moon knows Diedrich Knickerbocker's History of New York by heart. He told me that funny story of Oloffe Van Kortlandt and the Porpoises on the way down to Bowling Green to look for St. Nicholas where Oloffe saw him."

Washington Irving chuckled with delight: "So John Moon remembers Oloffe, does he? Knows Knickerbocker by heart, does he? I have been asleep a long, long time but I'm wide awake this Christmas Eve."

And stretching out both hands to the little Dutch boy who stood smiling up at him from the hearth rug he called: "Jump up, Nicholas! and I will tell you a marvellous tale of the Goblins who guard the gold in the Kaatskill Mountains."

And as Nicholas sat listening to the story of the Goblins he could see the good St. Nicholas flying north over the Hudson–beyond the Palisades to the Catskill Mountains. And the sides of the mountains opened as he passed and out trooped an army of strange little men, laden with glittering gold, who marched down to the river and piled their gold on ships that waited there, and as the ships sailed away into the moonlight, Nicholas heard the distant call of a trumpet, and taking Washington Irving by the hand he led him over to the window as St. Nicholas had told him. And as they stood there at the wide-open window of the great palace they heard men's voices singing and the tramp of marching feet.

"They are singing the great song of St. Nicholas," cried Washington Irving.

"Look! Oh, look! Nicholas, the Knickerbockers are coming!"

And leaning far out of the palace window, Nicholas saw a great company of men marching two and two in the moonlight, led by a jolly fat trumpeter. They wore broad-brimmed, black sugar-loaf hats on their heads, queer broad-skirted coats with big buttons, and wide breeches which reached to their knees. The silver buckles on their shoes flashed at every step they took, and great clouds of smoke rose from the long pipes they were smoking.

"There's Oloffe the Dreamer!" called Nicholas. "I know it's Oloffe marching on ahead."

"And there's Anthony Van Corlear blowing his own trumpet!" cried Washington Irving, "and Hans Reinier Oothout with his long spy-glasses, and that's old Walter the Doubter, the first to sit in the Governor's chair, and William, the restless one, with the cocked hat on the back of his head, with his windmills, and here comes old Hard-Koppig Peet in his brimstone-colored breeches, carrying a fiddle tonight in place of his sword."

"St. Nicholas likes him best of all," said Nicholas.

"And so do I," exclaimed Washington Irving. "Oh Nicholas, what a Christmas celebration we will have when we open the doors for the Knickerbockers to come in!"

"Quick, Sir!" exclaimed Nicholas, "or the Knickerbockers may be gone."

"You are right, Nicholas, there isn't a second to lose," and taking him by the hand Washington Irving led Nicholas swiftly across the room and opened a door leading into a dimly-lighted corridor guarded by great bronze gates.

CHAPTER IX

BROWNIE'S BIG PARTY

THE LIONS' SHARE

"I MUST run round the corner and tell the Library Lions to be on the look-out for Nicholas tonight," said the Brownie to the cook as she swept the last crumb from the floor of Lucky's kitchen.

Thirty seconds later the Brownie stood in front of the first Library Lion. He was looking very handsome, for he was covered with snow.

"Merry Christmas, Leo Astor!" she called. "Be on the watch for a strange boy from Holland just before midnight. He's coming to my party."

The first Library Lion stared at the Brownie and burst into a hearty laugh.

"Why, Brownie," said he, "that must be the very boy my brother and I have been talking about. My brother saw him cross Forty-second Street and go up past the city flag-staff early this afternoon and I saw him go down Fifth Avenue. I've never seen a boy like him before. Why don't you give him a big party and invite everybody?"

In a great flutter of excitement the Brownie ran across the plaza in front of the Library. "Merry Christmas, Leo Lenox!" she called to the second Library Lion who was looking equally handsome, for he too was covered with snow. "Be on the watch for a strange boy from Holland tonight. He's coming to my party."

Leo Lenox looked very superior as he replied: "You mean Nicholas I suppose. He came across Forty-second Street early this evening just after the old Troll passed along. I've been sitting here ever since the Library was opened, Brownie, and I've seen millions of people go by–my brother and I review all the celebrities as you know–but never before have we seen anyone like Nicholas looking for Christmas.

"Why don't you give him a big party and invite everybody? Everybody who came down from the LENOX,” roared Leo Lenox.

"Everybody who came up from the ASTOR," roared Leo Astor from the other end of the plaza.

"If you Lions will only roar like that I can do anything," cried the Brownie. "Nicholas shall have the biggest and best party that ever was given. I'll go straight back to the Children's Room and send out the invitations."

Up the long flight of steps to the Fifth Avenue entrance of the Library scampered the Brownie. "Merry Christmas, dear Colonel Flanagan!" she called to the stately old Guard who was closing the great doors for the night. "I'm giving a Christmas party for Nicholas. Please come if you can."

And Flanagan turned with a knowing smile as he said: "When I heard Leo Astor roaring for all his old friends from the Astor to be invited I thought I might be wanted to count them."

Through the great marble halls and downstairs to the Children's Room rushed the Brownie.

"Merry Christmas, Lucie Lenox!" she called to the statue of the girl crossing a brook, which stands outside the door of the Children's Room. "It's high time you had some Christmas fun. Jump down from your pedestal and come to my party for Nicholas."

Lucie Lenox first stared, then she smiled as she balanced herself on the log, and jumping down she followed the Brownie into the Children's Room with a hop and a skip. She had not been inside the room for years.

"The Boy Wizard was here while you were gone, Brownie," called Aladdin as the door opened, "and when he heard us all talking about the party he wanted to come himself. I told him you had given everyone a number but he only said, 'Rub your lamp for me Aladdin,' and disappeared."

"Where did he go?" cried the Brownie. "The Boy Wizard is the very one to help me with the party for he knows every nook and corner of the Library."

"He's gone where he goes every Christmas Eve, behind the Blue Door with David Blaize. Shall I call him back, Brownie?"

"No, never call a boy back from anywhere," said the Brownie, "he will come back when he is ready."

"Brownie," whispered Hasan of Bassorah very confidentially as he leaned far out of the Book of Wonder Voyages, "I've never felt right about the magic cap and rod I took away from the two little brothers who were quarrelling over them. They belong to boys, not men. I've been looking ever since for the right kind of a boy to give them to and from all I have seen and heard of this Boy Wizard he answers my requirements. He was born in one of the city towers–and although he was brought to this Palace of Books to live when he was but two years old he is not in the bondage of books, he speaks the language of all the little animals, the birds, and the fishes, loves music, knows great men when he sees them, understands magic, and sets store by his dreams. Shall I give the Boy Wizard the cap and rod, Brownie?"

"Oh, yes, Hasan, and be quick about it for the Blue Door is opening and the Boy Wizard is coming back!"

And as Hasan handed the magic cap and rod to the astonished Boy Wizard, the Brownie shouted:

"Hail to our Master of Ceremonies. Where's the Troll? I appoint him Chief of Police with power to choose his own officers. Aladdin, you will be responsible for the illumination of the palace.

"Hindbad, you will not merely guard all the portals, you will, like any true porter, wake up the sleeping ones from time to time.

"Sindbad, you will act as interpreter to Nicholas for the guests from the Oriental Department. It will be lots of fun and you can tell stories in Arabic whenever you feel like it."

THE BOY WIZARD'S PLAN

"Let's plan the way the party is going to be," said the Boy Wizard, and he sat down at the head of the long table with a glass top under which the Mappe of Fairyland lies.

Just as the Brownie, the Troll, Aladdin, Sindbad, and Hindbad were taking their seats, Puss-in-Boots walked in.

"Come along, Puss! we need your advice," shouted the Brownie. Puss surveyed the group for a moment, and then, with a low bow to the Brownie, he drew up a chair opposite the Boy Wizard.

"The first thing to be done," said the Boy Wizard, "is to open the Stuart Gallery for the reception. You remember, Brownie, it wasn't half big enough to hold the people who came to welcome Marshal Joffre. Suppose I use my magic rod on those walls and turn the whole front of the building into one big room? It would be jollier."

"I should say so!" cried the Brownie. "And then think of the costumes! They could actually look them up in the Prints Room and get them right for once," and the Brownie shook with laughter.

"We'll hold the banquet in the big Reading Room, of course," continued the Boy Wizard. "But we must change the tables and run them the length of the room instead of across, then we can seat hundreds more at the banquet for we can shove them up close together and use the galleries all round the room."

"I trust, Sir," said Puss-in-Boots earnestly, "that you will leave untouched the wall which separates the Banquet Hall from that Hall of Ancestral Shades commonly known as the Genealogical Room."

The whole group nodded their heads in approval of this wise counsel, and turning to Puss-in-Boots the Boy Wizard said, "No wonder the Marquis of Carabas depends on you, Puss. The same advice holds good for the opposite wall, for behind it sleep the Shades of the Sachems of the Five Nations in the American History Room."

Sindbad the Sailor turned to the Brownie and whispered, "Do you think anybody will come out of that room? I'd like to see an American Indian. I've never seen one."

"I don't know about the others, Sindbad, but I think the Leatherstockings will be here," the Brownie whispered back.