THE SNOWDROP

THE SNOWDROP

IN THE SPRING-TIME GARDEN

"Oh-ooo!"

It was a most delighted little cry. In fact, Phyllis was a most delighted little girl. Right here in her own garden was the first spring blossom. Phyllis's bright brown eyes shone eagerly, and her brown gold curls blew wildly as she rushed to the door to tell the family.

"It was my secret!" cried the little girl, dancing first on one foot and then on the other. "I've known for whole days that it was coming!"

"What is it?" cried Jack. "When did it arrive? Who brought it? What is it?"

"I think the sunshine brought it," said Phyllis. "I think that warm rain yesterday helped bring it. It is a little snowdrop. Come and see how lovely it is! How it hangs its pretty nodding head and how it lets the wind rock it!"

After the family had admired the little messenger of spring and gone back into the house, Phyllis still lingered.

"You are very lovely," said Phyllis, stooping lower over the little cluster of blossoms.

"I am so glad you have come. You see, when I put those dry-looking bulbs in the ground last fall, it seemed hard to believe that anything so dainty and delicate and sweet as you could come from them."

The snowdrop nodded sweetly at Phyllis's words of praise.

"I always come with the earliest spring sunshine," said the snowdrop.

"I wish I knew all about you," said the little girl, wistfully. "The birds and the bees have told me their stories. I should so love to know about the blossoms which come every summer to make me happy."

"I am a very simple flower," said the snowdrop, "but I have lived in the world for countless summers. If you like, I will tell you what I can of myself."

Phyllis drew closer to the little plant and softly touched it with her finger-tips.

"Do tell me," she said.

"I am one of the blossoms of spring," said the snowdrop. "I come to tell you that the long winter is over; that the summer will soon be here.

"I usually bear my blossoms in an umbel, though there is sometimes but a single blossom on a stalk."

"What is an umbel?" Phyllis wondered.

"An umbel, Phyllis, is a number of blossoms starting from a common centre on a single stalk."

"Your petals are not all the same size," said Phyllis. "I notice that though you really have six petals, the three outer ones are large and lap over the smaller inner petals. The outer petals are notched. How snowy white they are, and what a tender green are your grasslike leaves."

But the snowdrop only nodded its bowed head, and said not another word.

THE SEED

|

A wonderful thing is a seed; |

HOW THE SNOWDROP CAME

The whole earth was bare and desolate. The trees were bare, and the grasses were broken and brown. The snow fell fitfully.

Adam and Eve sat outside the Garden of Eden and remembered the beautiful green of the leaves and grasses, and the gorgeous colours of the flowers.

Then Eve shivered and sobbed softly to herself, for the earth seemed big and empty. All had once been lovely.

Then an angel in heaven looked down and saw Eve weeping. And the angel came down to comfort her.

As the angel spake to Eve a snowflake fell on her hair. The angel took it in his hand. "Look, Eve," said the angel, "This little flake of snow shall change into a flower for you. It shall bud and bring forth blossoms for you!"

As he spoke, the angel placed the snowflake on the ground at the feet of Eve. As it touched the earth it sprang up a beautiful flower of purest white.

And Eve, looking down, saw the blossom, and dried her tears and smiled in joy.

"Take heart, dear Eve," said the angel. "Be hopeful and despair not. Let this little snowdrop be a sign to you that the summer and the sunshine will come again."

And about the feet of Eve there sprang up through the snow numberless little white-cupped blossoms. Thus, the legend tells us, the snowdrop came to earth.

CALLING THEM UP

|

"Shall I go and call them up,– |

TO THE SNOWDROP

|

Pretty firstling of the year! –Barry Cornwall. |

ALL ABOUT THE SNOWDROP

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to amaryllis family.

Blossoms in early spring.

Common in gardens–grows from bulb.

Flowers generally on an umbrel–at other times single–in colour they are pure white, with drooping nodding heads. No cups for flower–three of the petals are longer than the other three. These are notched and lap over the shorter ones. Three cells to pod.

Leaves long, slender, grass-like.

THE

NARCISSUS AND THE TULIP

THE NARCISSUS AND THE TULIP

ALL IN A GARDEN FAIR

The tulips stood up very stiff and tall. They looked neither to the left nor the right, but straight up toward the sky. They lifted their stiff petals a little higher as if shrugging their shoulders. Their stiff stalks would have broken rather than have bent.

The great yellow daffodils stood in a long golden row just across the path from the tulips. They danced and bowed and shook their fluffy heads. They nodded in a very friendly fashion to their cousins, who huddled shyly together in the corner of the garden.

Now the daffodils' cousins were the narcissus blossoms who bloomed in quiet beauty in the garden corner. They were as tall as the yellow daffodils, and more slender.

They wore lovely broad white collars, and their golden hearts were bound with dainty pink or crimson. They seemed not half as proud and stiff as the tulips, nor half as gaudy and gay as the daffodils.

Indeed, the narcissus blossoms paid little heed to the more gaudy flowers. They just bloomed in quiet and peace for those who cared for them.

Phyllis stood in the midst of the garden and listened for the faint flower voices.

"Those are cousins of mine." The daffodil spoke to a scarlet tulip, and she nodded in the direction of the narcissus blossoms.

"Do you mean that the narcissus is a relation of yours?" asked the tulip, still looking skyward.

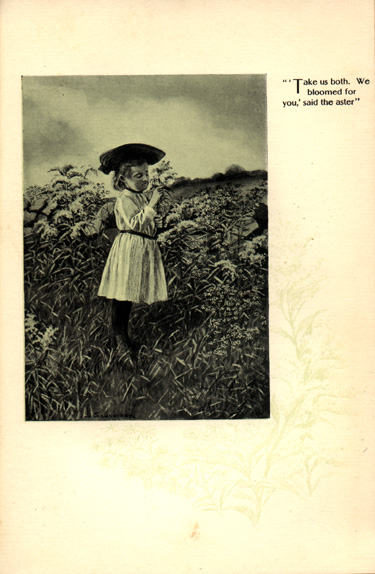

Phyllis stood in the midst of the garden

"Yes, indeed," said the daffodil. "We do not look much alike, to be sure. But our family name is the same."

"Now that you mention it," said the tulip, "I think there is a little resemblance. You both have those long, slender stalks and those grasslike leaves. But you wear yellow while the narcissus dresses in white and gold. What is your family name?"

"Both the narcissus and myself belong to the amaryllis family," said the daffodil, proudly. "My blossoms are larger and more showy, but there are those who like my cousin's dress the better. She is called the poet's narcissus, while I am daffodil narcissus–"

"But we children have a dearer name for you," Phyllis interrupted. "We call you little daffy-down-dilly."

The daffodil shook all her many skirts out proudly in the sunshine. Then she bowed three times until her head fairly touched the ground. The tulips still stared stiffly at the sky.

"We belong to the lily family," said one tulip, after a pause. "We wear gorgeous dresses and hold our heads proudly because Mother Nature bade us do so.

"We are dear friends of those wonderful creatures, the bees. The butterflies, too, sometimes visit us."

"I think," said Phyllis, shyly, "that the butterflies must be your cousins, or, at least, you must get your dresses from the same loom."

The tulips could not bow, but one less stiff than the others actually shook so hard with laughter that a section of its dress fell off.

"What a dear little girl," said the quiet poet's narcissus from the corner. "I am glad that we live in her garden."

It was Phyllis's turn to bow and run into the house for tea.

DAFFY-DOWN-DILLY

|

Poor little Daffy-down-dilly! |

NARCISSUS

Once, in a far-away country, there lived a handsome youth whose name was Narcissus. He was a very beautiful young man. His hair was as yellow as the flax stalks when they are ripe. His eyes were as blue as the flax flowers when they bloom. His face was as pink and as white as the clouds in a morning sky.

But Narcissus sat beside a stream and wept. He looked neither to the right nor to the left. His tears flowed fast, and his heavy sobs were the only sound to be heard in the wood.

Then there came roaming by the brook side a maiden. She was as beautiful as the cool shadows of the woodland. She was as gentle as the spring breezes among the grasses. She spoke to Narcissus.

"I am Echo, the maid of the hills and the wood," said the maiden. "Long have I watched you as you mourned. Often have I called and you did not heed.

"I know the cause of your grief, Narcissus. I have heard how you once had a lovely twin sister. She was the very image of yourself.

"I have heard how your lovely twin sister has now crossed the river of Death. Now you mourn day after day and will not be comforted.

"Look up, Narcissus, I pray you! Your tears cannot bring your sister again to you. Look up, and I, Echo, will comfort you!"

Now the voice of Echo was soft and sweet, and her words were kind, but Narcissus did not look up. He bent farther over the stream which flowed so slowly just there.

As he glanced down into the water, Narcissus started in surprise. He thought he saw his sister looking up into his eyes from the quiet depth of the water. Again and again did Echo call, but Narcissus no longer even heard her voice.

Still Narcissus gazed at his own reflection in the water, thinking that he looked into the eyes of his lost sister.

Day after day he sat there gazing, and sorrowing that he could not reach her. The face in the water looked sad, and Narcissus would fain have comforted his sister.

Not for one moment would he leave the brook side. Not for one instant would he heed the sad, sweet pleadings of Echo.

Thus, sorrowing for his lost twin sister, Narcissus died. Then the voice of Echo, the beautiful, became softer and sadder. Her form became more and more slender until at last she could no longer be seen, though her voice might still be heard.

Then one day there sprang up by the brook side a slender, beautiful flower, as white as the cheeks of the maiden, as yellow as the hair of the youth.

Its blossoms bent over the water, and their reflections swam beneath. And the drooping willows, which hung over the stream, looked down at the strange new blossom, and touched leaves and whispered: "It is Narcissus. It is the youth Narcissus."

And the soft, sighing voice of the formless maiden, Echo, replied, "Narcissus!"

GRANDMOTHER'S GARDEN

|

Stately and prim grew the hollyhocks tall, –Dorothy Grey. |

A TULIP STORY

In the sweet long ago, there lived a lovely old lady in the midst of a most beautiful garden.

The old lady was quiet and gentle, and the flowers seemed to know her and grow for her as for no one else.

They sprang up beside every path.

In the earliest spring-time her tulips lifted up their stately heads and bowed as she passed among them.

The sweet old lady watered the flower-beds and pulled weeds from among the plants, and loosened the earth about their feet that they might grow taller and blossom more beautifully.

One evening after sunset, the old lady sat quietly in her garden. She watched the tulips as they rocked gently back and forth.

She heard faint, sweet whisperings among the flowers and amid the long grasses.

"They sound like the whisperings of the fairies," said the sweet old lady to herself.

"Indeed," she went on, softly, "I have often heard that the fairies dance in the dell below. Why, then, should they not sometimes wander into my garden?"

"Why not, indeed?" laughed the faintest fairy voice right in the sweet old lady's ear.

Looking up, she saw the most wonderful little creature in soft, fluttering robes of shaded green. Her red-gold hair floated in a cloud over her shoulders. Her milk-white fairy feet peeped from beneath the shimmering skirts.

But most wonderful of all, the little creature bore in her arms a baby! It was the tiniest little pixie baby, wrapped so completely in its dainty green blankets that only a wee tip of its pink nose could be seen.

"I am the Queen of the Fairies," said the tiny mother, as she gently rocked her baby to and fro. "It is but right that I should let you know that we come often to your beautiful garden."

The sweet old lady looked at the Queen of the Fairies and smiled.

"I am truly glad that you find my garden a fit place for fairies," she said. "I have often been told that you danced in the dell. I have sometimes even fancied that I heard the faint, sweet tinkling of fairy music in my garden. But never before have I been sure that you really came."

"Do you know," said the fairy, softly, for the fairy baby stirred in her arms, "do you know that it is here we come to sing our babies to sleep?"

"Then I did hear fairy music?"

"You heard the cradle-songs of the fairies, and sometimes you heard the cooing laugh of the fairy babies before they fell asleep. Sometimes you heard the soft swish of fairy dresses as we softly slid away to dance in the dell."

"And you left your babies sleeping in my garden!" said the sweet old lady, wonderingly.

"Ah," laughed the Queen of the Fairies, "where else would they have been so safe? Your tulips kept our secret well.

"They never told you that it was fairy nurses who rocked their stems so gently in the moonlight and the starlight. You thought it was the wind that swung their tall stalks.

"You did not know that in the morning each tulip held her head so proudly because all night long a fairy baby had been cradled in her heart.

"When you saw our babies' silver drinking cups which the nurses hung in the sun to dry, you called them dewdrops which sparkled in the sunlight."

"No," said the sweet old lady, "I did not know all those things. Neither did I know why my tulips grew so tall and fragrant and beautiful. But now I see it all, for fragrant and dainty and sweet must be the cradles of the babies of the fairies."

The Queen of the Fairies laid her finger to her lips with a low "Sh-h," and, looking down, the sweet old lady saw that the fairy baby was fast asleep.

The tiny mother seemed to blow across the old garden to the tallest golden tulip of them all. Then, softly singing, she laid her precious little one in the stately cup which rocked every so gently in the moonlight.

"I must be off to the dell," said she, a moment later. "You will see that no harm befalls the cradles of our babies?"

"Yes, yes," cried the old lady, eagerly. "So long as I live I shall watch over my garden with care. I will not allow one blossom to be broken from its stem."

The Fairy Queen thanked her, and the old lady was left in the garden with the fairy babies and the fairy nurses who rocked the fairy cradles.

But look as she might, the spell being broken, the sweet old lady could see nothing but her own beautiful tulips bending and bowing the moonlight.

For many years the sweet old lady kept her garden. For many years she heard the soft sighs of the fairy babies and the whispering songs of the fairy mothers. For many years she watched the fairy cradles as the fairy nurses rocked them in the soft, mellow moonlight.

Then at length the sweet old lady died and was buried in the little churchyard. The blossoms of her garden drooped on their stalks, withered, and died.

One day the old lady's son came to the spot. He was a coarse, rough fellow, and he did not love nor understand flowers.

"Flowers are but nonsense!" said he. "I shall plant parsnips in this garden. They will be good to eat!"

Then it was that the fairy mothers drew the fairy babies closer in their arms and left the garden for ever.

"He cares for nothing but eating," said the fairies, as they danced together in the dell. "But we do not forget the sweet old lady. He shall never raise parsnips in her fairy garden."

So the parsnips which the son planted did not grow. As soon as the seeds sprouted the young plants withered and died.

"It is of no use," said the son, when again and again he had failed. "But it is strange how those useless flowers which my mother planted would grow on this same spot."

The fairies, hidden in their soft green robes amid the weeds and the grasses, laughed softly together, then danced away to the churchyard. There they scattered seeds on the grave of the sweet old lady, and they watered the seeds from the drinking-cups of the fairies.

Soon there sprang up in the churchyard flowers as tall, as fragrant, as beautiful as those which had once grown in the garden of the fairies.

And even to this day, if you creep softly to the spot when the moon is full and the clocks are striking twelve, you may see the stately tulip cradles bend and sway in the moonlight. Even to this day, if you listen, scarcely breathing, you may hear the soft sighs of the fairy babies as they stir in their tulip cradles, and, listening still, you may hear the soft whispering songs of the fairy mothers as they croon soft fairy music over their darlings, on their return from their dance in the dell.

TO DAFFODILS

|

Fair daffodils! we weep to see –Robert Herrick |

ALL ABOUT THE NARCISSUS

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to amaryllis family.

An early spring blossom–found in gardens–grows from bulb.

Poet's Narcissus.–Stem naked and flattish–about a foot in height–usually one flowered. Flower pure white, but the centre, which is short and flat, is a rich yellow, rimmed with crimson or pink.

Daffodil Narcissus.–Single flower on stem–it is a golden yellow with deeper yellow cup on the naked flower stalk. Very common in gardens–is generally double.

Six stamens–three cells to pod.

Leaves–long, slender, grass-like, with a sort of rounded ridge on under side.

ALL ABOUT THE TULIP

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to lily family.

One of the early blossoms of the garden–herb–grows from bulb.

Stem long, leafless, and unbranching, bearing a single blossom.

Leaves all start from the ground, as do lily of the valley, etc.–leaves are rather broad and thick.

Flowers bell-shaped–six distinct petal-like divisions–colours varied, ranging in many shades of red and yellow, or in a mixture of the two colours.

THE ARBUTUS

THE ARBUTUS

FROM UNDER THE PINES

The postman rang the bell earlier than usual that morning. To Phyllis he handed a good-sized box well wrapped in brown paper.

"It's from Auntie Nan!" cried Phyllis, in frantic haste to cut the string. "It's from Auntie Nan! I know her writing! What can it be?"

By this time the string was unfastened, and the brown paper torn off. Phyllis slipped the cover.

"Oh!" she said, as though her breath were quite taken away.

"Oh!" and her pink little face was buried in the box. "Oh, where did you come from?"

The pink, pink bloom of the arbutus smiled up at her, and the delicious fragrance filled the whole room.

There were great masses of the small, fragrant blossoms. Phyllis happily lifted them from their box, and filled a big glass bowl with them. This she placed on the table in the dining-room. Their sweetness greeted all as they entered the room.

In the bottom of the box was tucked a note from Auntie Nan. It was directed to Phyllis. Would you like to read the letter?

"Dear little Spring Blossom:–Here are some of your little sisters come to keep your birthday with you. I know you will be glad to welcome them, especially when I tell you that I found them huddled snugly under some brown leaves and half covered with snow.

"'We are Phyllis's birthday blossoms,' they seemed to say, as I brushed away the leaves and the snow, and they looked bravely out.

"So I gathered every one I could find; and I send them to you, little girl, because they make me think of a certain sweet little pink and white baby your mamma sent for me to come and see just eight years ago.

"Are you not glad that you, too, are a little Mayflower, and that your birthday comes on the very first day?

"You know, your friend, the poet, Whittier, calls these little wild wood flowers which I am sending 'The first sweet smiles of May'?

"Did I say that these flowers grew out on the hill among the pines where you played last summer? They tell me that the arbutus is particularly fond of pine-woods and light sandy soil.

"Do you not call them brave to peep forth so very early? But, you see, they were really very well protected by their own heart-shaped leaves, which kept alive and green all winter just for the sake of those blossoms which were to come.

"I think it is no wonder that the Pilgrims, after that first hard, hard winter, were so happy to welcome this little messenger of spring. They called it the Mayflower. We people of New England still call it the Mayflower, but by others it is called the trailing arbutus. Sometimes, too, I have heard it called 'mountain laurel.'

"I have no doubt but that the story of the Pilgrims is quite true, for the flower still grows in its lovely sweetness all about the hills of Plymouth.

"Are you not glad that I call them your flowers, Phyllis? Are you not glad that to us, you, too, are one of 'the first sweet smiles of May?'

"Wishing that all Mayflowers may bloom more and more sweetly as the seasons go, I am,

"Your loving

"Auntie Nan."

TRAILING ARBUTUS

|

Darlings of the forest! –Rose Terry |

ALL ABOUT THE TRAILING ARBUTUS

OR MAYFLOWER

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to heath family.

Blossoms in April and early May.

Found in woodland, especially among pines, under the dead brown leaves of autumn–grows best in sandy soil.

Stem is covered with fine hairs of rusty brown–is trailing like a vine.

Flowers are small, clustered, and very fragrant–in colour vary from purest white to deepest pink–hidden under its own broad, protecting leaves–five sepals–corollas five-lobed, hairy inside–pistil one–stamens ten.

Leaves are evergreen–on hairy stalks, heart-shaped and thick.

JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT

JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT

ABOUT A LITTLE PREACHER

Jack was reading an Indian story. He had not spoken for an hour. He only shook his head when Phyllis invited him to walk in the woods with her.

Now she peeped into the library, rosy-cheeked, bright-eyed, laughing. Jack was still with the Indians.

"Jackie, dear, there are some friends of yours waiting in the parlour," said Phyllis.

"They're late," said Jack, throwing his book down.

"Just in season," said Phyllis with a faint giggle.

In a moment, Jack came back. He was half-frowning, half-laughing.

"You fooled me that time, little sister," he said. "There is no one waiting for me!"

"Oh, yes, big brother, there is a whole family in there. They are just in season. Come, I will introduce you, since you seem to have forgotten."

Phyllis led Jack into the parlour. Still he saw no one. She led him up to little side table. On it stood a vase and in it stood–

"Jack-in-the-pulpit, let me introduce Jack-my-big-brother," and then Phyllis fell into a big chair and laughed.

"Phyllis," began Jack, crossly, for now he remembered that he had left the Indian story unfinished.

"Jack-in-the-pulpit is talking to you," said Phyllis, holding up a finger warningly. "You are very rude. I'm sure you did not bow to his wife."

"How do you know which is Jack and which is Mrs. Jack?" he asked.

Phyllis opened her eyes wide.

"I'm s'prised," she said, solemnly. "I see I shall have to tell you all about your name-sakes.

"Do you see how staunchly Jack stands in his pulpit? Nowadays our pulpits are not covered over, but they used to be in olden times. In England to this day you may find these roofed pulpits."

"There are some in the old Colonial churches of New England even now," said Jack.

"Do see how gracefully this little fellow's pulpit-leaf arches!" said Phyllis. "It is light green with veins of dark green. Jack is particular, and always preaches from a green pulpit."

"But here is a pulpit stained with purple," said Jack.

"Oh, that is Mrs. Jack-in-the-pulpit. That is the purple hood which she wears to church when her husband preaches."

"Well," said Jack, "her bonnet looks exactly like the pulpit."

"Except the colour," explained Phyllis.

Jack stood a moment examining the quaint green flowers.

"I know another name for him," he said. "These plants are called 'memory-roots' by some."

"Why?" Phyllis questioned.

"That's just what I asked Will the other day, and he said if I would bite into the root of the plant I'd find out."

"And you found out?"

"I did!" answered Jack, with a wry face. "My tongue was almost blistered. It is sore yet. I know now why it is called 'memory-root.'

"Will told me afterward that the Indians boiled these roots for food. He said he tried it himself once when he was camping and playing Indian. The acid seems quite gone after cooking, and they are rather tasteless and good for nothing. Please, little sister, may I go back to my story now?"

"You may," said Phyllis, laughing, "if you think the sermon is over!"

"I came near not understanding the sermon," said Jack. "Do you know what he said to me?"

"Yes," said Phyllis, "I hope I shall always listen as you did, Jackie."

I wonder if you know what the children meant by the lesson that those little green flowers taught Jack.

JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT

|

Jack-in-the-pulpit –Clara Smith |

ALL ABOUT THE JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT

OR INDIAN TURNIP

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to arum family.

Blossoms through the month of May.

Found along the edges of deep woods or in lighter spots in the forest.

Usually two leaves on long stems or petioles–these leaves are divided into three leaflets, with loose wavy margins–leaves taller than blossom.

Flower–green with markings of a deeper green or purple–the "Jack" is a spadix which bears the pistils and stamens–the "pulpit" is an enfolding leaf which curls over the flower in a graceful, protecting curve–from this curved leaf the plant receives its name, it seeming to resemble those old-fashioned roofed pulpits.

The "pulpit" is of a bright green, in some plants veined with a darker green, and in others stained with purple–the colour is said to show the sex of the plant–the females wearing the purple.

The fruit is a close cluster of scarlet berries–ripe in June or July.

Plant derives its name of "Indian turnip" from the fact that Indians find the bulb-like base edible.

THE PANSY AND FORGET-ME-NOT

THE PANSY AND FORGET-ME-NOT

IN MAMMA'S ROOM

Mamma had been ill for a whole week, and could not leave her room. At last she was able to sit up.

Outside in the hall there was the stealthy tread of two little pairs of feet. There was the gentlest of little taps. There was a warning "Sh." Then mamma cried, "Come in."

Jack opened the door, and Phyllis entered, with her hands behind her. Jack followed, with his hands behind him.

"Guess, mamma, dear!" cried Phyllis. "Guess what we have for you!"

"An apple?" guessed mamma.

"Something sweeter," said Phyllis.

"Candy?"

"Something sweeter," said Phyllis. "Do you give up?"

"I give up," said mamma.

The little girl placed a basket of forget-me-nots on the broad, flat arm of her mother's chair.

The little boy placed a basket of pansies in full bloom on the other arm of the chair.

"Oh," cried mamma, "how lovely! It's like bringing the garden into the room."

"Just what we said," Jack cried. "We saw these baskets of flowers as we came up from the square, and we bought them for you. You see they are planted and blossoming nicely for you. They will be just right for your window. Shall we put them there?"

"By and by," said mamma. "I want to see first if these flowers will talk to me as they do to Phyllis."

"Why, of course," said Phyllis. "I only get their secrets by watching."

"I know a lovely name for the pansy," said mamma. "My grandmother used to call pansies heartsease. I always think of her when I look into their bright little faces.

"The pansy is a relative of the violet, you know. In fact, I think it is a violet grown more gorgeous by cultivation."

"Yes," said Phyllis, "it has five petals, just as the violet has. The two upper ones are larger and longer than the other."

"Just look at the soft, velvety colours," said Jack. "See how they nod on their green stems. Never more than one blossom on a stalk, is there?"

"No, no," laughed Phyllis. "And look the heart-shaped leaves. They are thick and strong and green."

"I believe I like the forget-me-not best," said mamma. "It belongs to an entirely different family. It is not so gorgeous as the pansy, but it blossoms all summer long, just as the pansy does, and its blossoms seem to look up at one like little blue eyes uplifted.

"Look at the delicate blossoms in tiny bunches. Do you see how round and flat the corolla is? We call it salver shaped. A salver, you know, is a flat tray–and that is the reason we say the forget-me-not is salver shaped.

"Its leaves do not grow as pansy leaves do. They grow upon the stem with the blossoms, and there are many of them. They alternate upon the stem, and they are small and pointed."

"Does it grow only in gardens?" Jack asked.

"Oh, no, indeed; in some places it grows wild, in low, wet places, or on the banks of streams. But I shall be very happy with these little blossoms on my window-sill. Will you put them there for me now?"

"Mamma," said Phyllis, "I found a little forget-me-not poem yesterday. Shall I say it for you before we go?"

"Yes, indeed, that would be a very sweet way of saying good night."

So Phyllis placed the baskets in the window, and, coming back, stood before her mother and repeated these lines:

"When to the flowers so beautiful,

The Father gave a name,

Back came a little blue-eyed one,

All timidly it came.

And standing at its Father's feet,

And gazing in his face,

It said in low and trembling tones,

And with a modest grace,

'Dear God, the name thou gavest me,

Alas, I have forgot.'

The Father kindly looked Him down,

And said, 'Forget-me-not.' "

Mamma's eyes were closed when Phyllis finished, and the children tiptoed softly out of the room.

THE FOOLISH PANSY

|

A dainty little pansy –Jenny Wallis. |

THE PANSY

|

Out in the garden, wee Elsie –Eben E. Rexford. |

THE PANSY'S STORY

A modest floweret bloomed in the glade. So shy was she that she crept into the shadow of a tall leaf. Then she spread her blossoms.

Soon there crept out from the shadows of the tall leaf an exquisite, delicate perfume. Soon there crept under the tall leaf a little singing bird, who spied the purple and gold of the floweret's blossoms. When he flew out he sang of her sweetness to all the world.

At last, one day, an angel flew down to earth with a mission of love. Now the long white wings of the angel swept close to earth. They brushed aside a tall leaf. The angel discovered the blossoms of purple and gold. She inhaled the exquisite, delicate perfume.

"Ah!" cried the angel. "How lovely you are! Too lovely to dwell alone in the shadows. You should be a flower in the gardens of the angels.

"But wait, I have thought of something even more beautiful for you. You shall be the angel's blossom, but you shall bloom in the land of man.

"Go, sweet pansy, bloom in every land. Bring to all people sweet thoughts of peace and love and faith."

Then the angel stooped and kissed the floweret, and lo, from each little blossom looked out a tiny angel face.

So it happened that the pansy came into our gardens to live. When you see the tiny faces in her blossoms will you remember the angel whose kiss was kindness and gentleness and love?

THE STORY OF THE FORGET-ME-NOT

One morning, in the golden days of the early world, an angel sat just outside the gates of Paradise, and wept.

"Why do you weep?" gently asked one who passed that way. "Surely the world is lovely, and Paradise is so near!"

"Alas!" said the angel, "I must wait long before I may enter Paradise."

"Why," said the other, "it seems but a step to the gates. Why must you wait?"

"Look," said the angel, pointing earthward. The other looked and saw a dainty blue-eyed maiden stooped over the grass by a brookside.

"Do you see those tiny blue flowers which she is planting?" whispered the angel. "They are as dainty as she is herself. They are blue as her own eyes. They have hearts of gold as true as her own true heart."

"Why, then, do you weep?" asked the other.

"Ah," said the angel, "I love the gentle maiden, and with her I would have entered Paradise. But, lo, when we came to the very gates we were not allowed to enter."

"Tell me more," said the other.

"A task was given to this earth maiden," said the angel. "In every corner of the world must she plant this tiny blue flower. I may not enter the gates of Paradise without her. Thus it is that I sit outside and weep."

"Nay, nay," said the other. "weep not. There is a better way than that."

Then he whispered in the angel's ear.

And the angel flew to earth where the maiden stooped over her dainty blue flowers. He came to assist her in her task.

Hand in hand the angel and the beautiful maiden wandered over the land. In every corner of the earth they planted the blue forget-me-nots.

Then one day, when the task was done, they sat together beside the stream and wove wreaths of forget-me-nots.

And with garlands of their own flowers about them, the angel gathered the beautiful maiden in his arms and carried her with him to the gates of Paradise.

The gates swung wide at their coming, and ever after the angel and the maiden whom he loved wandered mid fields of happiness in the land of Paradise.

ALL ABOUT THE PANSY OR HEARTSEASE

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to violet family.

Blossoms throughout summer into late fall.

Stem–slender–nodding–single flower on stalk–low.

Leaves grow in cluster about the root and on stem–sometimes cut–often heart-shaped.

Five petals–five sepals–five stamens–one pistil–one-celled pod–lower petal has a little spur–beautifully colored in shades and mixtures of yellow, violet, and purple.

ALL ABOUT THE FORGET-ME-NOT

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to borage family.

Blossoms throughout the summer.

Found along the banks of streams and in low, marshy places.

Stems–slender, branching, somewhat rough when rubbed upward.

Flowers–light blue, small, on a one-sided raceme, coiled up at the tip and unfolding as the flowers open–calyx five-lobed–corolla is round and flat, or salver shaped–stamens five–there is a white species of the flower.

Leaves–small and pointed–broader at the base–alternate.

THE WILD ROSE

THE WILD ROSE

BANKS OF ROSES

On the last day of June, Phyllis and her best doll went for a walk. It was a delightful day to walk. The sunshine was not too hot, nor the wind too strong.

Phyllis and her doll wandered a long way. At last they found themselves on a country road. On one side of the road was a ditch. Beyond the ditch was a steep, high bank.

When Phyllis looked across to the high bank she gave a cry of delight. I am shocked to say that she dropped her very best doll in the grass, and forgot all about her for at least ten minutes!

Do you wonder why? That steep bank was just thick with rose-bushes. They were in full bloom, and looked so fresh and pink and sweet sitting on their rustling beds of green leaves! Is it any wonder that Phyllis wished to get to them as soon as possible?

She gave a wild leap across the ditch, and landed right in the midst of the wild roses.

"Oh!" cried Phyllis, the next instant. "Oh, you have hurt me! You are not so lovely, after all!"

The pinkest pink rose of them all tossed her head jauntily.

"We are only protecting ourselves," she said. "Mother Nature told us to use our thorns when we were in danger."

Phyllis looked down, a little ashamed. At her feet was a broken stem and a crushed rose.

When she returned to the roses, Phyllis came more gently

"I didn't think I should jump so hard," she said. "And I didn't know your thorns were so sharp. I really did not intend to harm you.

"I will set the broken rose in the water of the ditch. Perhaps it will live for a little time there!"

When she returned to the roses, Phyllis came more gently than she did the first time. The pinkest pink rose nodded in a more friendly fashion.

"How long have you been here?" Phyllis asked, still feeling a little hurt by her unfriendly reception.

"Oh, we bloom here year after year," said the pink rose. "This roadside bank is our home. We have never been away from it.

"The rose-bush and the thorns are here the whole year. But the flowers and leaves do not last so long.

"The tender green leaves came out early in the summer. My sister blossoms shook out their pink skirts a day or two ago. Yesterday I was just a bud with a pink, pink tip. The day before that I was a green bud with no pink tip."

"Your pink dress is very beautiful," Phyllis said.

"Yes, but it fades in the sun, and it does not last long. Look at my sister on your right. Her dress is almost white. A day or two ago it was deep a pink as my own.

"Look at my sister on your left. Her dress is coming to pieces. One petal has already fallen.

"Look at this little baby bud beside me. Her pink skirts are all rolled up inside her green cloak. To-morrow she will slip out of the coat and come out to play with the wind and the sunshine."

The wild rose touched the baby bud playfully. Then she rose again on her stem.

"But we do not stop growing just because our dresses become old and fall to pieces. Do you see the green cup below my petals, and the green ball which will some day be twice as large and quite as lovely as my pink dress now is?"

"Oh," said Phyllis, "that is your seed-cup."

"When autumn comes the leaves will turn brown and fall off," said the pink rose. "By that time this green ball will be filled with seeds, and it too will have changed colour.

"Every rose-bush by the roadside will bear bunches of crimson berries instead of pink-skirted roses. If you come by in the autumn and see us, Phyllis, I should be glad to have you pick me and carry me to your home. I have never in the world been away from this bank."

"Indeed," said Phyllis, "I will be sure to remember. I will remember, too, not to jump into your home so rudely that you take me for a burglar."

Then Phyllis again jumped across the ditch and gathered up her neglected doll. Together they walked home without a single pink rose in her hands, but with a good number of scratches from the roses' thorny stems.

TWO LITTLE ROSES

|

One merry summer day –Julia P. Ballard. |

THE MOSS ROSE

Once a little pink wild rose bloomed by the wayside. To all who passed her way she threw out a delicate perfume and nodded in kindly welcome.

The larks and the humming-birds all loved the pink wild rose. The baby grasses and the violets snuggled up at her feet in safety. To all she was kind and sweet and helpful.

One day Mother Nature passed that way. She saw the gentle wild rose sending out her helpful cheer to all. Mother Nature was pleased.

She stopped a moment on her way to speak to the simple flower. She praised the wild rose for her sweetness and her beauty and her kindness. At last she promised her her choice of all the beautiful things that were in the store of Nature.

The pink wild rose blushed quite scarlet at the praise. For a moment she stopped to think.

"I should like," said the wild rose, blushing more and more, "I should like to have a cloak from the most beautiful thing you can think of."

Mother Nature looked down at her feet. She stooped. She arose and threw about the blushing pink rose a mantle of the softest, greenest, most beautiful moss.

Mother Nature passed on her way.

The sweet rose by the roadside drew her mantle of moss closely about her and allowed it to trail down the stem. She was very happy. She was never again to be called the simple wild rose, but in her heart she knew that her beautiful mossy mantle would only help her in spreading sweetness and kindness and beauty and the perfume of happiness through Mother Nature's world.

HOW THE SWEETBRIAR BECAME PINK

Eve was young, and she walked in the Garden of Eden. Countless as the stars were the nodding heads of the flowers of her garden. Sweeter than the perfume of a hundred summer-times was the fragrance of her blossoms.

Eve looked again and again, and was never weary. She wandered for many happy hours in her Garden of Eden.

One morning, she again walked forth, she spied a rose of purest white. It was the sweetbriar, and when Eve approached, delighted with the blossom, the whole plant sent out from every leaf a sweet, delicate perfume. The pure white rose lifted its cup eagerly.

"Ah," said Eve to the white sweetbriar rose, "you are beautiful. You are exquisitely sweet!"

She drew the blossom down to her and kissed its white petals with her sweet red lips.

So when the sweetbriar rose swung back to its place its petals were pale pink. They had drunk the colour from Eve's red lips.

THE TRANSPLANTED FLOWER

"Every time a good child dies, one of God's angels comes down to earth and takes the dead child in his arms, then spreads his large white wings and flies over all the spots which the child best loved and plucks a whole handful of flowers, which he carries up to the Almighty, that they may bloom in still greater loveliness in heaven than they did upon earth; and the Almighty presses all such flowers upon His heart, but He gives a kiss to the one He prefers, and then the flower becomes endowed with a voice, and can join the choir of the blessed."

These words were spoken by one of God's angels, as he carried a dead child to heaven, and the child heard him as in a dream; and they passed over the spots in his home where the little one had played, and they passed through gardens filled with beautiful flowers.

"Which shall we take with us and transplant into the kingdom of heaven?" asked the angel.

There stood a slender, lovely rose-bush, only some wicked hand had broken the stem, so that its sprigs, loaded with half-open buds, were withering around.

"Poor rose-bush!" said the child; "let's take it, in order that it may be able to bloom above, in God's kingdom."

And the angel took it and kissed the child for its kind intention, and the little one half-opened its eyes. They plucked some of the gay, ornamental flowers, but took likewise the despised buttercup and the wild pansy.

"Now we have plenty of flowers," said the child, and the angel nodded assent; but did not yet fly upward to God. It was night, and all was quiet; they remained in the large town, and hovered over one of the narrow streets, where lay heaps of straw, ashes, and sweepings. There lay fragments of plates; pieces of plaster of Paris, rags, and old hats, and all sorts of things that had become shabby.

And amidst this heap the angel pointed to the broken fragments of a flower-pot, and to a lump of mould that had fallen out of it, and was kept together by the roots of a large, withered field-flower, which, being worthless, had been flung into the street.

"We will take it with us," said the angel, "and I will tell you why as we fly along."

And as they flew, the angel related as follows:

"In yon narrow street, a poor, sickly boy lived in a lonely cellar. He had been bed-ridden from his childhood. In his best days, he could just walk on crutches up and down the room a couple of times, but that was all. During some days in summer the sun just shone for about half an hour on the floor of the cellar, and when the poor boy sat and warmed himself in its beams, and he saw the red blood through his delicate fingers, that he held before his face, then he considered that he had been abroad that day. All he knew of the forest and its beautiful spring verdure was from the first green sprig of beech that his neighbour's son used to bring him, and he would hold it over his head, and dream that he was under the beech-trees, amid the sunshine and the carol of birds.

"One spring day the neighbour's boy brought him some field-flowers besides, and among them there happened to be one that still retained its root, and which he therefore carefully planted in a flower-pot and placed in the window near his bed. The flower was planted by a lucky hand; it throve and put forth new shoots, and blossomed every year. It became the rarest flower garden for the sick boy, and his only little treasure here on earth; he watered it, and cherished it, and took care it should profit by every sunbeam, from the first to the last, that filtered through that lonely window, and the flower became interwoven in his very dreams; for it was for him it bloomed; for him it spread its fragrance and delighted the eye, and it was to the flower he turned in the last gasp of death, when the Lord called him. He has now been a year with his heavenly Father, and for a year did the flower stand forgotten in the window, till it withered. It was therefore cast out among the sweepings in the street on the day of moving; and this is the flower, the poor faded flower, which we have added to our nosegay, because this flower gave more joy than the rarest flower in the garden of a queen."

"And how do you know all this?" asked the child, as the angel carried him up to heaven.

"I know it," said the angel, "because I myself was the little sick boy who walked on crutches; I know my own flower."

And the child opened his eyes wide, and looked full in the angel's serenely beautiful face. At the same moment they reached the kingdom of heaven, where all was joy and blessedness.

And God pressed the child to His heart, when he obtained wings like the other angel and flew hand-in-hand with him; and God pressed all the flowers to His heart, but kissed the poor withered field-flower, which then became endowed with a voice. It joined the chorus of the angels that surrounded the Almighty, where all were equally happy.

And they all sang, great and little, the good, blessed child, and the poor field-flower that lay withered and cast away among the sweepings under the rubbish of a moving day, in the narrow, dingy street.

–Hans Andersen.

A CHRISTMAS ROSE

The old black pine on the mountainside cast a long dark shadow across the thin covering of snow which covered the whole mountain and even the valley below.

The cold winds blew fiercely and the old black pine waved his shaggy arms fitfully and laughed at the soft snowflakes that nestled themselves fearlessly among his long needles.

"Ho! Ho!" laughed the old black pine. "Ho! Ho! winter has come, but I do not fear him. The flowers have gone, but I shall brave the winter storms. I shall laugh at them as I have done for countless seasons."

Then a fiercer blast of wind struck the pine-tree and bent his tall head so low that he saw a little plant growing at his very feet. It was a hardy little mountain rose, and it had two buds already half-open. The pine-tree also heard a weary little sigh.

"Why do you sigh and fret?" asked the pine-tree, his shaggy arms spread to protect the plant.

"Alas!" said the rose-plant, "the other plants are long since asleep. I wish I might bloom when the others do. My buds are beautiful, but who is there to admire them?

"What fun it would be to blossom with the blue-eyed gentian or the lovely goldenrod. They would have admired my blossoms. But now no one cares. I see no use in blooming at all. Oh, dear! Oh, dear!"

"Ho! Ho!" laughed the old black pine. "Ho! Ho! What nonsense you talk, little friend. The snowflakes and I will admire you. Do not be a grumbler.

"Do you not remember that you are a little Christmas rose? You are named for the Christ Child. You should be more happy and contented than other plants.

"Be brave, little rose. The snow is growing deeper about you. Push up and keep your head above the drifts. Care well for your precious buds, that they may open into perfect blossoms.

"Keep up heart, little rose. You do not know yet for what purpose you were left to bloom so late. But be sure of this: we were all made for some wise purpose. When the time comes, we shall know."

Then shaggy pine fingers of the old tree touched the rose with a gentle caress as he lifted his tall head once more to the winds. He did not speak again, but the little rose nestling at his feet, thought long of the old pine's wise advice.

"Perhaps he is right," she murmured to herself. "Perhaps I had better do as he said. All the other flowers are dead. If I was made for a wise purpose I shall not long be forgotten."

So the mountain rose lifted her leaves bravely. She sighed no longer. She took good care of her beautiful buds, and watched them as day by day they grew.

It was the day before Christmas when the buds opened lovely and white and perfect. The old pine saw them, and bowed his head to admire the blossoms. He shook all over as he laughed down on the blossoms peeping up through the snow.

"Ho! Ho!" laughed the dark old pine. "Who is unhappy now?" and the blossoms smiled back contentedly.

That day two little children wandered hand in hand up the mountainside. Their father was the woodcutter who lived in the tiny hut below.

Their mother was the pale, sick woman who lay in the tiny hut and answered her children by neither look nor word.

By their mother's bed sat the father, speechless with grief. About the room moved the kind neighbour with tears in her eyes.

"Our mother is very ill," whispered the children. The kind woman shook her head sadly.

"I fear," she said, "that your mother will not live till sunset."

Then, sobbing softly, the two little children stole out of the door. Hand in hand they walked on, scarce knowing where they went. At last they came to the foot of the black old pine.

"Come," said the boy. "The old pine does not care for our grief. Let us go to the valley. There we will find people with kind hearts. They will care for us."

The girl opened her soft, sad eyes and stared at the boy.

"Poor boy!" she said. "Your grief has made you forget. There is always the Christ Child who cares. To-morrow is His birthday."

Then she spied the Christmas roses blossoming so perfectly in the snow.

"Let us take these roses," said the children, "and go to the church. We will pray that our mother may yet live."

The old, white-haired pastor met the children at the church door. Together they entered and prayed. The roses, nodding in the little girl's hand, seemed now to understand why they had bloomed so late.

That night the mother's fever turned. The mother began to grow better. There was joy in the little hut.

ALL ABOUT THE WILD ROSE

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to rose family.

Blossoms in early summer.

Found along streams and roadsides.

Is a low bush–stems woody–stems and branches generally covered with frail prickles.

Leaves–smooth, dark green, from five to seven leaflets, coarsely toothed–alternate.

Blossoms single–calyx is urn-shaped, narrowing at the top–to its lining are fastened pistils and stamens–corolla consists of five (generally) broad petals, varying in colour from white to deep rose pink–buds are deep pink–fruit crimson in the autumn.

THE BUTTERCUP

THE BUTTERCUP

IN THE PASTURE

"Don't tread on me," cried a flower voice at Phyllis's feet.

"Who are you?" asked the little girl.

"I belong to the crowfoot family," said a buttercup, holding her head up very proudly. "Some folks call us the gold of the meadow."

"Some folks call you weeds," said Phyllis. "My brother Jack says that no one but little girls care for buttercups. He says that even cows won't eat you."

"No, indeed," said the buttercup. "I shouldn't like to be eaten by cows. I am glad of the bitter acid in my stem. It protects me. I have no doubt it has saved my head many a time."

"You stand very proudly upon your hairy stem. And so you may stand, for I shall not touch you. If I did, the juice from your stems would probably make my hands smart and itch and burn.

"But you are pretty," Phyllis went on. "How satiny your five yellow petals are, and how erect your stem is! I should judge it to be about three feet high."

The buttercup raised her head a little higher.

"Did you grow from a seed?" Phyllis asked.

"No, from a bulb, but some buttercups grow from seeds, I think. I am the early buttercup. Later in the season will come the fall buttercup. It will be very much like me, save that it will not be so tall nor so large as I. I am sorry that you do not like me as well as you do the wild rose. I really have not treated you as badly as she."

"Well," Phyllis said, "you do seem to be very friendly, and you seem to grow on cheerily without the least encouragement."

"Yes, it's a way we weeds have a way of doing," said the buttercup, serenely.

"Nothing any one can say or do seems to make the least difference to you. I have seen old Boss pass you by with just a single sniff many a time."

"That, too, is because I'm a weed. I'm a sort of plant tramp. I can live almost anywhere. I do not need encouragement nor praise. I am not useful, and yet I am happy."

"I do think you are pretty," Phyllis said. "But I am on my way to the pond, where Jack has been building a raft. He has promised me a ride."

"Good-bye," said the buttercup. "When you have time, look up the story of how buttercups happened to grow in the world."

THE GOLD OF THE MEADOW

Do you believe there is a bag of gold hidden away at the end of the rainbow? Do you think if you could only get there before the rainbow fades you would surely find the gold?

Well, don't you ever run very far to find the end of the rainbow. Shall I tell you why?

Well, then, the bag of gold is no longer there. It is much nearer home, and I can tell you the exact spot to find it! Go down in the meadow where the buttercups grow, and there you will find the gold which was once hidden at the end of the rainbow.

Long ago, just as you have so often heard, the bag of gold lay at the farther end of the rainbow. But, long ago, somebody found it. Have you never heard about it?

Many, many people looked for the gold, and they failed to find it. At last they came to say that no one could ever get it.

It seems almost sad, then, to find out that at last the bag was certainly found by a miserly old man.

This old man was selfish. He was cross. He was unpleasant, and likewise unhappy.

When he found the gold, he wished no one to know of it. He feared that some one might need some of his precious gold. So he decided to hide his wealth in the earth.

So one dark night, when black clouds scurried across the sky and not a star was in sight, the old miser went to bury his gold. He slung the big bag over his shoulder and crept along the dark meadow where the grass was thick and tall. It was, in fact, the self-same meadow in which the fairies danced, but this the old man did not know.

Now the fairies are always good and wise and loving. They do not like selfishness, and they love to do kindnesses for others. But fairies are also sometimes full of mischief. Listen, and I will tell you what one fairy did!

As the old man crept slyly along, a fairy spied him. With a laugh she ripped a hole in the bag with a sharp grass blade. Of this the old man knew nothing.

One by one the gold pieces slipped down among the grasses. Little by little the bag grew lighter, but the old man did not notice, so eager was he to reach the wood before any needy one saw him.

His bag was empty before he reached the wood, but all amid the grasses shone the gold which he had dropped.

"Let us put it on stems, that all may see," said the fairies. "Let the fairy gold be free alike to rich and poor!"

So all night long the fairies worked. When morning came the sun shone down on the meadow which was bright with gold, each piece set on a sturdy stem of its own.

"You may call them buttercups, if you wish," laughed the mischievous fairy, "but they are fairy gold just the same!"

ALL ABOUT THE BUTTERCUP

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to crowfoot family.

A summer blossom–May to July.

Common in meadow and pasture lands.

Leaves from root–with three divisions–cleft and notched or toothed.

Stem erect–about a foot in height–hairy.

Early Buttercup.–Bright, clear yellow–sepals turn back–five in number–petals five, six, or seven–round and quite large–bulb at bottom of stem.

Later Buttercup.–Taller than early buttercup (from two to three feet)–petals not so large nor flower so showy as earlier flower.

THE IRIS

THE IRIS

WITH WET FEET

Phyllis trudged on to the pond without gathering a single buttercup. From the hilltop she saw Jack in the middle of the pond. In his hand was a long pole, and under his feet the tottering raft.

"Come along!" Jack shouted, pushing the raft toward the bank.

"Are you quite sure it is safe?" Phyllis asked, looking doubtfully at the bobbing raft.

"To be sure!" Jack replied, in a tone which made Phyllis sure he thought her afraid. "Haven't I been paddling about here the whole morning? I'm not the least bit wet. Come on!"

So Phyllis clambered on with her brother's assistance. She sat huddled in a little heap in the centre of the raft. Jack drove his pole against the bank and pushed off.

"You needn't be so scared," he said, half-scornfully, "the water isn't deep enough to hurt you any. If our ship should sink, it would be in only two feet of water."

"I could get very wet in only two feet of water," began Phyllis, but a sudden lurch of the raft interrupted her.

Jack scarcely looked at her. Phyllis knew that he thought her very silly. By and bye she grew used to the raft, and was no longer afraid. She even moved a little and laughed when Jack splashed in the water with the pole.

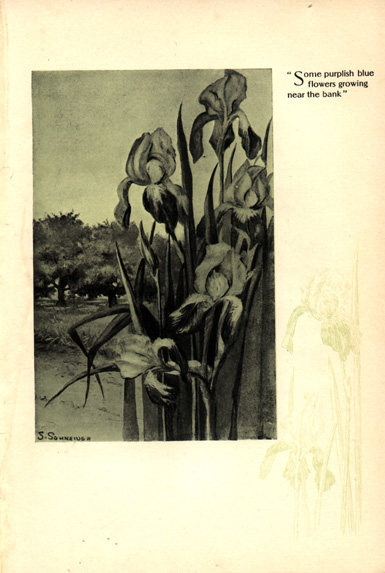

Some purplish blue flowers were growing near the bank

"Isn't this jolly?" asked Jack, when they were almost across the pond.

"It is, indeed," said Phyllis. "I think I shall stay with you the whole morning."

Then her bright eyes caught sight of some purplish blue flowers growing near the bank.

"Oh, brother, push up and get them for me!" she cried.

Jack gave a mighty push and sent the raft in among the reeds and rushes. But, alas, the raft struck a root, and with the jar Phyllis slipped off into the water. By good fortune she landed on her feet. There the little girl stood right beside the blue flowers which she had wished for.

Phyllis began to laugh. So did Jack.

"Well," said he, "why didn't you wait? I didn't know you were in such a hurry. Why don't you pick them now?"

So Phyllis broke off several stalks and some of the long sword-shaped leaves. She could feel the water between her toes.

"I think my feet are very wet," she said. "My stockings are all 'squashy.' "

Then Jack remembered what a cough Phyllis had in the winter. She had been obliged to stay in her room and drink flaxseed tea. Jack had really been sorry as well as lonely.

"Come," he cried, "get back on the raft, and I will get you ashore. I don't want you to be ill again."

In a few moments he reached the sunny bank.

"But I don't want to go home," said Phyllis, wriggling her wet toes.

"Perhaps you could dry your shoes and stockings here in the sunshine," said Jack. "It is very warm."

So the shoes and stockings were laid in the sunshine to dry, and Phyllis sat on the bank with her blue flowers. Jack pushed off again.

"You are beautiful," said Phyllis to the flowers. "May I ask your name?"

"Do you not know the iris?" asked one flower. "We have grown in your pond for years and years. We are called by several names. One of these names is blue flag.

"The French people call us fleur-de-lis. They chose us as their national flower. It is still the emblem of France."

"Your colours are very lovely," Phyllis said. "Your petals appear blue, but through them run tiny veins of purple and white."

"Not every iris blossom is of this purplish blue shade," said the blossom. "Some are creamy yellow. Some are a lovely brown. But we all have six petals, three of which turn back and reveal the yellow crest. The three upper petals stand erect and arch over the three stamens.

"The best friend I have is the bee," the iris went on. "If it were not for his help I could never bear seeds. But the bee is known to love my colours. Besides, he knows of the nectar I have stored up in my heart for him.

"So Mr. Bee often alights on one of my large recurved petals. Then he creeps down into my heart for the nectar. As he does so, I shake my pollen on his head and ask him to bear it to another iris across the way.

"This he does gladly. On the very next flower that he enters he drops the pollen in the place where it will fertilize, and cause the seeds to grow."

"How did you get the name of Iris?" Phyllis asked.

"Oh, Iris, you know, was the rainbow messenger. When she came to earth with a message, she first threw her rainbow bridge across the sky and allowed one end to touch the earth. You know the lovely rainbow colours. Do you not see how many rainbow colours there are in my dress? That is how I came to have the name of Iris."

Phyllis reached over and felt of her stockings. They were quite dry and warm.

"I do not believe I have taken cold," she said.

"It is very queer to think that it will hurt you to get your feet wet," said the iris. "Why, I have stood in the water all my life. I grew tall and strong and beautiful, and I've always had wet feet. Even now I begin to feel quite faint and wish I might stand again in some cool water."

"And so you shall," laughed Phyllis. "Little girls and little blue flags are very different children." And she set the blossoms down in a shallow pool among the reeds until she should be ready to go home. Then once again she tried the raft. Jack was more careful this time, and Phyllis did not try again to stand like the iris with her feet in the water.

THE RAINBOW MESSENGER

It was the festival day of the flowers. Every beauty from Flower Land flaunted her fair blossom in the clear sunshine. Every plain but useful plant sat demurely and reflected on her own importance. Every common, useless plant stood in honest wide-eyed admiration of the others.

All were dressed in their very best. It was indeed a scene of wondrous beauty. It seemed a difficult thing for the judges to choose which was fairest.

At the last moment there came breathlessly into their midst a new flower. Her robe was deep blue like the sky of twilight. It was as delicately shaded as the clouds of sunset. It was trimmed with fluffy golden bands. It was jeweled with dewdrops from the pond.

"Who is this beautiful stranger?" asked the judges in a breath, and the beauties from Flower Land stared in surprise, knowing that the newcomer was more beautiful than they.

But no one answered the question of the judges. No one knew the fair stranger in robes of blue. She did not speak for herself.

For a moment there was silence at the festival of the flowers. Then one of those wide-eyed, useless ones whispered in the judge's ear:

"Do you not see the rainbow colours of her robe?" she asked. "Do you not see the raindrops sparkling in the sunshine? Surely it is Iris, the rainbow messenger. Look again at her gown!"

"Iris! Iris!" whispered the flowers together. "Let us call her Iris the Beautiful!"

So it was that every judge, every beauty from Flower Land, every plain but useful plant, and every common, useless plant, chose Iris for their queen of beauty.

ALL ABOUT THE IRIS, OR BLUE FLAG

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to iris family.

Blossoms in May and June.

Found in wet meadows and boggy places.

Stem stout and jointed–angled on one side–one stem may bear several flowers–from one to three and a half feet high.

Leaves stiff, flat, sword-shaped, folded together for sometimes half their length, sheath-like fastening to stem.

Flowers a little taller than leaves–blossoms are violet-blue with veinings of purple, yellow, white, and green–corolla six cleft–the three outer divisions are large and curved back–the three inner divisions are smaller and stand erect.

Seed capsule one and one-half inches long, then lobed.

THE POPPY

THE POPPY

IN SCARLET DREST

The poppies were dancing in their garden home. The morning breezes were their partners.

They swung and they curtsied. They scraped and they bowed. They spread their scarlet skirts and bent so low that their slender stems seemed in danger of breaking.

Phyllis, as she came down the walk, caught the flutter of the gay skirts of the poppies, and drew nearer to watch the merry dance.

At last the breezes passed, as those little whirling breezes have a way of doing. They left the poppies quite breathless and quiet. One poppy's neck was broken in the last wild whirl, and she stood with drooping head.

In the very centre of the poppy bed stood a tall, stiff poppy with a fluffy white head. She was very lovely, but, being quite old, was too stiff to dance as the younger ones did.

"Those whirlwind breezes are wild things," said the old white poppy. "See, they snatched a handful of my white hair and threw it on the ground. They are very rude."

"Did it hurt?" asked a bud with drooping head.

"Why, of course it didn't hurt," said a newly opened blossom, who held her head erect upon her hairy stem. And the old white poppy shook her head stiffly.

"What a merry family you are," said Phyllis. "You have been blossoming all summer long. Do you like our garden?"

"We double poppies never grow except in gardens," said the old white poppy. "But some of these single poppies escape from the garden where they really belong, and grow wild in the fields. They shake out their four petals there, and pretend that the fields are their real homes.

"They do not always wear scarlet skirts either. Some poppies are white and some are purplish-blue. Other poppies were bright yellow dresses.

"But wherever poppies grow they are play-fellows with the breezes and the sunshine. You may always see them dancing and shaking their full skirts.

"Over in India great fields of poppies are raised. From the juice a kind of medicine is made. So you see, while here in your garden we are only ornamental, yet there are times when even poppies can be useful."

"My mother says that we are of use always if we are cheerful and happy and sunshiny," said Phyllis, running on down the walk.

THE CORN-FLOWER AND THE POPPY

Long ago there was a king who had one beautiful daughter. To her was given whatsoever she desired. Men servants and maid servants waited to do her bidding.

So it chanced that the little Princess became a spoiled and willful child. She never thought of the wishes of others. She always followed her own desires.

The little Princess was vain, and admired her own beauty. She always wore gowns of beautiful red silk. They were as soft and as gaily coloured as the petals of the gorgeous garden poppies.

Every morning the gentle, careful little maid combed the Princess's long dark hair with a golden comb.

At noontime she carried to the Princess a golden plate loaded with the finest ripe fruit. She offered her foaming, creamy milk in a cup of gold.

At eveningtide the maid robed the Princess in a nightgown of silk, and tucked her snugly in the softest and downiest of silken beds.

When the Princess slept, the little maid drew the silken curtains of the bed, and herself slept on a couch close by, that she might waken at the Princess's least movement.

The maid was always gentle, patient, and obedient, and her eyes were as true and blue as the petals of the corn-flower, and her hair as golden as the stalks of the ripe wheat in the field.

One day the Princess sat on the wide veranda on the shady side of the palace. The little maid fanned her with a fan of sweet-scented grasses. Afar in the field the reapers were at work in the harvest.

"Come," said the Princess. "Bring my parasol of bright red silk, and we will go to the fields and watch the harvesters."

The little maid bowed so low that you could not see the blue of her eyes, only the gold of her hair and the blue of her gown. She hastened to bring the red silk parasol, and together they found their way to the harvest field.

Now the reapers loved their king and respected him. For his sake they loved the wilful little Princess. When the Princess and her maid reached the field the workmen stopped their work for a moment and bowed respectfully before the two little girls. The Princess tossed her dark head saucily, and twirled her red silk parasol impatiently. She spoke scornfully to the honest workmen, and bade them go about their work.

But the little maid smiled kindly upon the honest workmen. So though it was to the Princess that the workmen bowed, it was into the blue eyes of the little maid that they looked. It was the flutter of her simple blue gown which they caught as they looked back across the fields.

Now the Princess was weary from her long walk across the fields. She commanded the maid to find her a place in which to rest. The little maid found a soft place on the shady side of a shock of golden wheat, and brought cool water from a stream close by.

As she sat there the Princess looked far out across the fields, and away on the horizon she saw a long, slender, black streak of cloud. She sprang to her feet and clapped her hands and called loudly to the workmen. From their places in the field they came running to do her bidding.

"See!" cried the Princess, pointing with her umbrella, "a storm is rising. Build me a cabin from your sheaves. Be quick! I am the Princess! I am the king's daughter!"

The workmen sprang to do as she wished. But one old man who had long served her father, the king, bowed low before the Princess and spoke.

"Oh, beautiful Princess," he said, "pardon me, but there will be no rain. That is not a rain cloud. See how brightly the sun shines!"

The Princess screamed with rage.

"How dare you?" she cried. "How dare you? Is not the command of your Princess enough? Do you refuse to obey?"

"Your pardon, Princess," said the old man, sadly. "There is not a man in the field but would gladly lay down his life to serve the Princess. But your command is useless, and the sheaves are precious."

The Princess was speechless and white with anger, but she still pointed to the dark cloud which was slowly sinking away.

Quickly the reapers built the shelter for the Princess. They knew that the good sheaves which they wasted might have made bread for their children. Therefore it was sadly that the reapers wrought, knowing that the long winter would surely come.

Presently a tiny house was finished. With golden sheaves of the ripe grain were the floors laid. With sheaves were the walls built. With sheaves were the roof covered.

When it was completed, the Princess lowered her red silk parasol, and, still frowning, passed inside. "Come in!" she cried, sharply, and the little maid, with tears of pity in her blue eyes followed. The workmen turned again to the uncut grain and said nothing.

By this time there was no cloud to be seen in all the blue heavens. The air was clear and cool. But the Princess and her little maid sat within the house of sheaves.

Then without a second's warning an awful thing happened! From the clear sky came a flash of lightning. From the cloudless sky came a roll of thunder.

From the harvest field shot up red tongues of flame, for the house of sheaves was on fire. The burning sheaves fell about the selfish Princess and her little maid. Nothing could save them.

When the flames died out, nothing was left but a heap of gray ashes.

Then the old man who had begged the Princess not to command the workmen's time for a useless whim turned away. He went sadly across the stubble fields and in at the great palace gates. He went straight up the steps to the throne where sat the king and queen. To them he told the fate of the two little girls.

The parents were heart-broken. They mourned long for their little daughter. As the days went by and they sat in their loneliness they came to see that they had made a great mistake in letting their child pet her own selfishness. When they saw this, they bowed their heads and wept aloud.

The following summer at harvest-time the reapers came upon two new flowers blooming in the spot where the house of sheaves was built.

One flower was tall, and stood up proudly among the wheat. Its petals were as silky and scarlet as the gown of the Princess. In the breezes it tossed its head haughtily.

Beside the scarlet poppy grew a pretty little blue corn-flower.

"As blue as the eyes of the little maid," said the workmen in a whisper. "As dainty and simple as the fluttering blue gown she wore!"

Then, turning slowly, they went again about their reaping, leaving the corn-flower and the poppy blooming side by side.

ALL ABOUT THE POPPY

SUGGESTIONS FOR FIELD LESSONS

Belongs to poppy family.

Blossoms throughout summer and fall.

Cultivated, grows in gardens–in Turkey and India it is cultivated for the opium it contains.

Stem from one to three feet high–hairy.

Leaves, divided, cut, and toothed–alternate, rather grayish green in colour.

Blossoms of garden poppies of numerous colours–the white poppy is the opium poppy–petals are four in number, very much crumpled in the bud–buds droop on stem, but flower is erect.

THE SHOOTING-STAR

THE SHOOTING-STAR

AMONG THE GRASSES

"Come with me," said Jack. "I will show you where the shooting-stars grow."

Phyllis did not need a second invitation. She snatched her hat and ran after her brother.

In a few minutes they crawled under the fence which guarded the railroad track. For a while they walked the ties. Phyllis's short legs began to grow weary.

"Look out, now," said Jack. "You go on this side of the track, and I will go on the other. They are right along here!"

In a moment there was a glad cry from Phyllis.

"Here they are!" she cried. "Come over. There are just bushels of them!"

But Jack told her that there were quite as many on his own side of the track.

The shooting-stars were not in the least hard to find. They stood up tall and straight, and shook their blossoms out in lovely fragrant clusters.

"What tall, reddish-brown stems they have," said Phyllis. "They are so bare and so straight, not a leaf on them. They must be at least two feet tall."

Then she looked down at the bottom of the flower stems. There were the leaves in a cluster about the foot of the flower. These leaves were oblong, and lay close to the ground.

At the top of the bare stems grew the blossoms. These flowers were in clusters of fives or sevens, their short stems starting out from the same place on the mother stem.

The blossoms themselves were lovely. In colour they were white, pink, and sometimes a pale lilac.

The petals were long and narrow and broader at the tip than at the base. They not spread out as petals generally do. They turned back and huddled quite close to the mother stem. In fact, they entirely hid the five brownish-green sepals underneath.

But the stamens were far from being hidden. There were five of them, and they stood out brown and stiff. Their tips came together and formed a cone which was tipped with yellow, and somewhat in the shape of a bird's bill.

"Ah," said Phyllis, when she saw these stamens, "I see why some folks call you bird's bill. I see, too, why they call you shooting-stars."

It was not long until the children's arms were full of the long-stemmed, leafless blossoms.

They were very sweet and fragrant. Their colours were very delicate and lovely.

"Let us put them in the big flower-jars in the library," said Phyllis.

"All right," said Jack. "I will fill the jars with water. You may arrange the flowers."

"And then we will call mother to see," said Phyllis, preparing to crawl under the fence and hurry homeward.

THE SHOOTING-STARS

Once, in the time called long ago, the little stars up in the sky jogged and jostled each other sadly.

"Why do you push and crowd?" said their calm, quiet mother, the moon.

"Our big brother, the evening star, will not allow us to shine!" cried the little stars. "We think, O Mother Moon, that there are too many stars in the sky!"

"Do stand still," the evening star exclaimed. "How can I shine steadily with a lot of little stars twinkling about on my toes?"

"Children! Children!" said the Mother Moon, roundly.

"Oh," said one of the little star babies, "I wish we might live down on the earth. There are acres of room down there. How happy we might be on earth!"

"We would not need to stand so still down there," said another star baby, longingly.

"Would it really please you to live on the earth?" asked their father, the Night Wind.

Every star baby twinkled and danced and beamed happily out at the Night Wind.

"Oh," cried they, "may we go?"

"Fold your pink and white dresses closely about you," said the Night Wind. "Fasten on your hearts these little shields of gold. I will carry you to the earth."

So there in the middle of the night, after the evening star and the big calm moon were fast asleep, the little stars slipped from the sky.

Down and down and down the Night Wind carried the little star babies. With their pink and white dresses folded closely about them they sped on and on.