The Wood Carver's Wife

And Later Poems

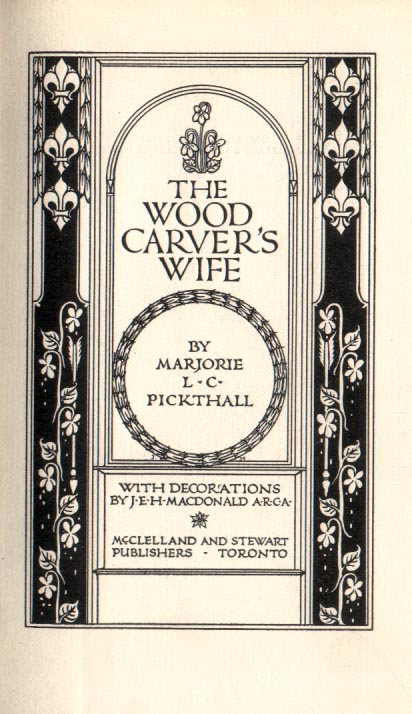

THE

WOOD

CARVER'S

WIFE

BY

MARJORIE

L.C.

PICKTHALL

WITH DECORATIONS

BY J.E.H. MACDONALD A.R.C.A.

MCCLELLAND AND STEWART

PUBLISHERS ❤ TORONTO

COPYRIGHT, CANADA, 1922

by MCCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED, TORONTO

Printed in Canada

Poems included in this book have appeared in the London Times, the Century Magazine, the University Magazine, The Youth's Companion, the Dial, the Sunset Magazine, the Woman's Home Companion, and the Smart Set, to all of which acknowledgments are due.

M. L. C. PICKTHALL.

Dedication

LORD, on this paper white,

My soul would write

Tales that were heard of old

Of perilous things and bold;

Kings as young lions for pride;

Lost cities where they died

Last in the gate; the cry

That told some Eastern throng

A prophet was gone by;

The song of swords; the song

Of beautiful, fierce lords

Gone down among the swords;

The traffick and the breath

Of nations spilled in death;

The glory and the gleam

Of a whole age

Snared in a golden page,–

Such is my dream.

Yet thanks, if yet You give

The crumbs by which I live,–

Blown shreds of beauty, broken

Words half unspoken,

So faint, so faltering,

They may not truly show

The blue on a crow's wing,

The berry of a brier

Cupped in new snow

As though the snow lit fire, . . .

Marjorie Pickthall: A Memory

It was in June and amid the wild loveliness of sea and forest that the writer first saw the manuscript of this book. The author of it sat where great rocks wedged a fallen log–fallen so long that its dead, gray bark had changed to the many greens of velvet mosses. Below lay the Pacific and above and far back the mountains rose. Forest sounds, secret and musical, accompanied the rise and fall of the poet's voice as she turned the pages, reading here and there. When she had finished little was said–silence and the dim loveliness of the place seemed the most fitting comment; beauty had melted into beauty, making each more beautiful.

It is inevitable that a note of sadness should attach itself to a book whose author has not lived to see its publication. Yet at the risk of being accused of sentiment, it may be worth while to insist that, to the poet, publication, though a happy thing, is never the supremest joy. Not in recognition, but in creation, is to be found that incommunicable thrill, the echo of what God felt when he made a world and saw that it was good. Perhaps it was because in Miss Pickthall's mind these essential values were never confused, because she saw so clearly and chose so unhesitatingly the better part, that her work has been singularly untouched by considerations lesser than the high demand of her art. The easy ways were not for her, but rather the long patience, the single-hearted waiting upon that breath of inspiration which answers no summons save its own. Certain it is that to this attitude of hers we owe these lyrics in which every word gleams, a facet of the gem-like whole.

Besides this quiet yet deep belief in the sanctity of her work, Miss Pickthall possessed an originality of mind and a genius for rare and perfect phrasing which will strongly support her claim to real distinction. Her voice is never an echo. Kinship with other poets she has, but the origins of her inspiration are securely set within her own unique personality. And here it may be well to note that personality is a far wider thing than personal experience. And it is evident that Miss Pickthall very early grasped the happy fact that in the poet's winged imaginings lies the sure way of escape from every confining space and an open road to every denied experience. In this inspired fancy lies the sufficient explanation of how one possessing it may live so simply and yet feel and know so much. Could any mother have uttered a cry more poignantly true than "A Mother in Egypt"? And can anyone reading "The Wood Carver's Wife" doubt that its writer knew its passions and despairs, its exaltations and strange cruelties? To ask whence comes this sure and subtle knowledge is to ask the unanswerable. It is the poet's birthright–one can say no more than that.

But though tragedy is a high thing, joy is not less nobly born. In this poet, at least, there was a wealth of happy interest which linked her most companionably with the life of everyday. To her, a sense of humor was always the saving grace, the balance-holder which never confused the great things with the small nor let the sublime slip into the ridiculous. Tears were for secret places but laughter shared with a friend was a bond which made a closer bond more possible.

With such a sane combination of humor and mysticism to build upon, her work would undoubtedly have broadened with the years. But since she will write no more it is idle to speculate upon what she might have written. Rather should we treasure and enjoy the legacy which is ours–that portion of her rich endowment which she so generously gave.

The last poem written, in her own hand, in her manuscript book is "The Vision," and however we may interpret it, it rings most gladly confident. There is no hint here of work unfinished or promise unfulfilled, but a sure knowledge and content that

"Life and death are one."

ISABEL ECCLESTONE MACKAY.

Contents

Sleep

HERE is a house, so great, so wide

It will take in the whole world's pride.

Yet, when I looked, it seemed I saw

Only a vast room strewn with straw

That was threshed of moony gleams

And dew of branches and star beams.

Here cheek by cheek the drowsed souls lay

Still as leverets in the hay.

Merry it was to see in Sleep

How each soul had found his brother;

Here a king and there a sweep

Lay hand-fast and kissed each other,

There a queen that had been sad

Mothered in Sleep a shepherd lad,

And lovers saw the loved one's face

Star-like in a lonely place.

But the Lamp that gave them light

Was lovelier than the dreams of night.

Angels watched lest any steal it,–

Christ's own heart, laid here to heal it.

The Tree

IN the dim woods, one tree

Was by the cunning seasons builded fair

With the rain's masonry

And delicate craft of air.

Unknown of anyone,

She was the wind's green daughter. Her the dove

Made, between leaf and sun,

His murmuring house of love.

Quiet as a seemly thought

Her infinite strength of shade she stretched around.

Peace like a spell she wrought

On that encloséd ground.

Bred of such lowly stuff,–

Blown mast, a sheltering day, a tender night,–

Now stars seem kin enough

To company her height.

She knows not whence she grew.

So in my heart, from some forgotten seed,

The lovely thought of you

Towered to the lovelier need.

Miranda's Tomb

MIRANDA? She died soon, and sick for home.

And dark Ilario the Milanese

Carved her in garments 'scutcheoned to the knees,

Holding one orchard-spray as fresh as foam.

One heart broke, many grieved. Ilario said:

"The summer is gone after her. Who knows

If any season shall renew his rose?

But this rose lives till Beauty's self be dead."

So wrought he, days and years, and half aware

Of a small, striving, sorrowing quick thing,

Wrapped in a furred sea-cloak, and deft to bring

Tools to his hand or light to the dull air.

Ghost, spirit, flame, he knew not,–could but tell

It had loved her, and its name was Ariel.

From a Lost Anthology

IN A STRANGE LAND.

By an unnamed river-anchorage have we raised a shrine to Apollo. If these strange winds cool the grass where he sleeps, we know not, nor if he will hear us. But round about grows the dark laurel, and here also the young oak fattens her acorns against the end of the wheat-harvest.

SPARROWS.

When I was a child I woke early, and the sparrows chirped to me from the cool eaves of the house. Since then each morning have I recalled their merry voices. But those little birds have long flown to nest about the white feet of Proserpine, where I who alone remember them shall follow them alone.

THE ROSE.

Above the ashes of me, Rhodora, they planted a rose, but it died. Pity me that I died also who was also a rose.

THE SALT WELL.

I am a well of brackish water springing from the unfruitful sand hard by the striving sea. Wherefor men have named me for Love, since all wayfarers must drink here, and drink again, lamenting the draught.

FRIENDSHIP.

When the black ships take thought of the sea and the winds are invoked, many are the dear gifts offered on the rocks to Priapus, and to thee, Leucothea of the clear hair; baskets of rye straw with ripe figs, and wine in curved sea shells. But to me Lysis gives a richer offering, even his grief and his farewell.

THE APPLE TREES.

I am an old man, but I have planted young apple trees along the dewy edge of my cattle field. Nymphs of the deep meadows, crowned with rue and fed on wild thyme honey, remember me when in years to come you rob me of my fruit.

THE SLEEPER.

Is there indeed a life after death? Then is sleep become a yet more precious thing. Wake me not.

A SHEPHERD.

Me when young, the mild-faded sheep followed. I fenced the folds, I sheltered the ewes, and at shearing time long strands of wool unwoven clung to my coat. Now by the fenceless sea I lay my bones and the foam blows over me, clinging to my bare tomb as white as wool. Yet am I far from the folds and the hill pastures of Thrace.

A POET.

That she will soon forget me, I know. Yet build my tomb high in the birch wood above the seaport road, so that the mariners who pass by singing my songs may pause, even if she bring me no myrtle. And plant strong saplings about it, and clean seeds, and cuttings from my rose garden, so that the birds may build there and the dry twigs blossom at the end of the winter. For I would not, O Cyprian, that the dove and the rose should forget me as soon as she.

A DEAF GIRL.

Here lies Chryseis, my bride. She was beautiful, but the gods of life denied her hearing. Nor have the gods of the dead been kinder. In proof whereof I come here daily and call her,–Chryseis, Chryseis. Witness thou, O stranger, she hath not heard me.

To Timarion

HAD I the thrush's throat, I could not sing you

Songs sweeter than his own. And I'm too poor

To lay the gifts that other lovers bring you

Low at your silver door.

Such as I have, I give. See, for your taking

Tired hands are here, and feet grown dark with dust.

Here's a lost hope, and here a heart whose aching

Grows greater than its trust.

Sleep on, you will not hear me. But to-morrow

You will remember in your fragrant ways,

Finding the voice of twilight and my sorrow

Lovelier than all men's praise.

Adam and Eve

WHEN the first dark had fallen around them

And the leaves were weary of praise,

In the clear silence Beauty found them

And shewed them all her ways.

In the high noon of the heavenly garden

Where the angels sunned with the birds,

Beauty, before their hearts could harden,

Had taught them heavenly words.

When they fled in the burning weather

And nothing dawned but a dream,

Beauty fasted their hands together

And cooled them at her stream.

And when day wearied and night grew stronger,

And they slept as the beautiful must,

Then she bided a little longer,

And blossomed from their dust.

Mary Tired

THROUGH the starred Judean night

She went, in travail of the Light,

With the earliest hush she saw

God beside her in the straw.

One poor taper glimmered clear,

Drowsing Joseph nodded near,

All the glooms were rosed with wings.

She that knew the Spirit's kiss

Wearied of the bright abyss.

She was tired of heavenly things.

There between the day and night

These she counted for delight:

Baby kids that butted hard

In the shadowy stable yard;

Silken doves that dipped and preened

Where the crumbling well-curb greened;

Sparrows in the vine, and small

Sapphired flies upon the wall,

So lovely they seemed musical.

In the roof a swift had built.

All the new-born airs were spilt

Out of cups the morning made

Of a glory and a shade.

These her solemn eyelids felt

While unseen the seraphs knelt.

Then a young mouse, sleek and bold,

Rustling in the winnowed gold,

To her shadow crept, and curled

Near the Ransom of the World.

Christ in the Museum

BRONZE bells and incense burners, and a flight

Of birds born out of iron, and fine as spray;

A dial that told the longest summer day

How sure, how swift the night:

And o'er the silent treasury, so high

No lips may kiss, no grieving hands have clung,

Numbered and ticketed, the Christ is hung.

The many pass Him by,

None pause. Here come no agonies, no dreams.

Nothing is here to hurt Him, nor to wake.

Year after year the golden iris gleams

A little paler by her lacquered lake,

And the dust gathers on the hands, the side,

The lonely head of Love the crucified.

The Chosen

CALLED to a way too high for me, I lean

Out from my narrow window o'er the street,

and know the fields I cannot see are green,

And guess the songs I cannot hear are sweet.

Break up the vision round me, Lord, and thrust

Me from Thy side, unhoused without the bars,

For all my heart is hungry for the dust

And all my soul is weary of the stars.

I would seek out a little roof instead,

A little lamp to make my darkness brave.

"For though she heal a multitude," Love said,

"Herself she cannot save."

The Coloured Hours

GRAY hours have cities,

Green hours have rhymes

Of hearts grown loving

In old summertimes,

But the white hours have only

A cloud in the sky

And a star, bright and lonely,

To remember them by.

Gold hours have laughter,

Red hours have song

Drawn from lost fountains

Of beauty and wrong.

But the white hours,–O, tender

As rose-flakes they lie,

With youth's fallen splendour

To remember them by.

Quiet

COME not the earliest petal here, but only

Wind, cloud, and star,

Lovely and far,

Make it less lonely.

Few are the feet that seek her here, but sleeping

Thoughts sweet as flowers

Linger for hours,

Things winged, yet weeping.

Here in the immortal empire of the grasses,

Time, like one wrong

Note in a song,

With their bloom, passes.

The Gardener's Boy

ALL day I have fed on lilied thoughts of her,"

The gardener's boy sang in Gethsemane.

"She is quick, her garments make a lovely stir,

Like the wind going in an almond tree.

She is young, she hath doves' eyes, and like the vine

Her hands enclose me,–hers as she is mine.

"She shall feed among the lilies where I am,

Learning their silver names. When evening grows,

One bower shall hold me and my love, my lamb.

Which shall I clasp," he sang, "her or the rose?"

When the palm shadow barred the juniper

He lay at last to sleep and dream of her.

He saw not those who came when night was deep

Up from the city, walking hastily.

One seemed a strong man wan for fear and sleep.

One bore a lantern. One moved stumblingly.

The gardener's boy dreamed on the sunburned sod,

Smiling beside the agony of God.

Bartimeus Grown Old

YEA, I am he that dwelt beside this tomb.

I was a child. God smote me from the sun.

A little while, I had forgot to run

Under the rain-sweet roof of almond bloom.

I had forgotten summer, and the flaw

Ruffling the gray sea and the yellowed grain.

Now I am old and I forget again,

But a man came and touched me, and I saw.

Long years he dowered me with imperial day,

Bright-blossomed night and all the stars in trust.

Now I am blind again, and by the way

Wait still to catch his footsteps in the dust.

Surely he comes?–and he will hear my cry,

Though he were stricken and dim and old as I.

Ecclesiastes

UNDER the fluent folds of needlework,

Where Balkis prick'd the histories of kings

Once great as he, that were as greatly loved,

Solomon stooped, and saw the dusk unfold

Over the apple orchards like a flower.

"O bloom of eve," he said, "diviner loss

Of all light gave us, dove of the whole world,

Bearing the branch of peace, the dark, sweet bough,–

Endure a little longer, ere full night

Comes stark from God and terrible with stars,

Eternal as He or love.

Now no one wakes,

But a lean gardener by my apricots,

Sweeping the withered leaves, the yellowing leaves

Down the wind's road. Perish our years with them,

Our griefs, our little hungers, our poor sins,

Leaves that the Lord hath scattered. He shall quench

The fierce, impetuous torches of the sun,–

Yea, from our dead dust He shall quicken kings,

Unleash new battles, sharpen spears unborn,

Shadow on shadow; but His stars remain

Immortal, and love immortal crowned with them."

Night came, and all the hosts thereof. He saw

Arcturus clear the doorways of the cloud,

And One that followed with his shining sons,

In the likeness of a gardener that strode

Over the windy hollows of the sky,

And with a great broom drave the stars in heaps,–

The yellow stars, the little withering stars,

Faint drifts along the darkness. New stars came,

Budded, and flowered, and fell. These too He swept,

And all the heavens were changed.

Then Solomon stood

Silent, nor ever turned to the Queen's kiss.

Singing Children

IN the streets of Bethlehem sang the children

So merry and so shrill,

"He shall have sweet cedars in his garden

And a house on Hermon Hill.

He shall have the king's daughter for his fellow,

A king's crown to bind upon his head."

And with bracken buds and straw, brown and yellow,

Mary made His bed.

In the streets of Nazareth sang the children

So clearly and so sweet,

"He shall lead us to the spoiling of the nations,

He shall bruise them with his feet.

His standards shall outface the stars for number,

Red as field-lilies when the rains are done."

And Mary heard them singing in her slumber.

And woke to kiss her Son.

In the streets of Jerusalem the children

Sang, passing to their play,

"The king's daughter waits in her apparel

All glorious as day.

We charge you, O ye watchmen, of your pity

Reveal us our belovéd, call his name."

And the shadow of a cross beyond the city

Fell softly o'er their game.

In the ways of all the world sing the children,

"We know Him, we have named Him, He is ours,

Like leaves we have fluttered to His shadow,

He has gathered us as flowers.

And when the bud falls all too soon for blossom

And when the play has wearied of its charm,

He bears the tired lambs within His bosom

And the young lambs in His arm."

Inheritance

DESOLATE strange sleep and wild

Came on me while yet a child;

I, before I tasted tears,

Knew the grief of all the years.

I, before I fronted pain,

Felt creation writhe and strain,

Sending ancient terrors through,

My small pulses, sweet and new.

I, before I learned how time

Robs all summers at their prime,

I, few seasons gone from birth,

Felt my body change to earth.

On Lac Sainte Ireneé

ON Lac Sainte Ireneé the morn

Lay rimmed with pine and roped with mist.

The old moon hid her silver horn

In shadow that the sun had kissed.

One went by like a wandering soul,

And followed ever,

By reed and river,

The silent canoe of the lake patrol.

On Lac Sainte Ireneé the noon

Lay wolf-like waiting by her hills.

No voice was heard but the sad loon

And the wild-throated whip-poor-wills.

But one went by on the bitter flaw,

And followed ever,

By rapid and river,

The swift canoe of the white man's law.

On Lac Sainte Ireneé the moose

Broke from his balsams, breathing hot.

The bittern and the great wild goose

Pled south before the sudden shot.

One fled with them like a hunted soul,

And followed ever,

By ford and river,

The little canoe of the lake patrol.

On Lac Sainte Ireneé the blue

Vast arch of night was starred and deep.

No footsteps scared the caribou

Nor waked the wolverine from his sleep.

Loosed indeed was the hunted soul,

And homeward ever,

By rapid and river,

Slipped the canoe of the lake patrol.

When Winter Comes

RAIN at Muchalat, rain at Sooke,

And rain, they say, from Yale to Skeena,

And the skid-roads blind, and never a look

Of the Coast Range blue over Malaspina,

And west winds keener

Than jack-knife blades,

And rocks grown greener

With the long drip-drip from the cedar shades

On the drenched deep soil where the footsteps suck,

And the camp half-closed and the pay-roll leaner,–

Say, little horse, shall we hunt our luck?

Yet. . . I don't know. . . there's an hour at night

When the clouds break and the stars are turning

A thousand points of diamond light

Through the old snags of the cedar-burning,

And the west wind's spurning

A hundred highlands,

And the frost-moon's learning

The white fog-ways of the outer islands,

And the shallows are dark with the sleeping duck,

And life's a wonder for our discerning,–

Say, little horse, shall we wait our luck?

Riding

IF I should live again,

O God, let me be young,

Quick of sinew and vein

With the honeycomb on my tongue,

All in a moment flung

With the dawn on a flowing plain,

Riding, riding, riding, riding

Between the sun and the rain.

If I, having been, must be,

O God, let it be so,

Swift and supple and free

With a long journey to go,

And the clink of the curb and the blow

Of hooves, and the wind at my knee,

Riding, riding, riding, riding

Between the hills and the sea.

The Woodsman in the Foundry

WHERE the trolley's rumble

Jars the bones,

He hears waves that tumble

Green-linked weed along the golden stones.

Where the crane goes clanging

Chains and bars,

He sees branches hanging

Little leaves against the laughing stars.

Where the molten metals

Curdle bright,

He sees cherry petals

Fallen on blue violets in the night.

When the glow is leaping

Redly hurled,

He sees roses sleeping,

Forest-roses in a windy world.

The Wife

LIVING, I had no might

To make you hear,

Now, in the inmost night,

I am so near

No whisper, falling light,

Divides us, dear.

Living, I had no claim

On your great hours.

Now the thin candle-flame,

The closing flowers,

Wed summer with my name,–

And these are ours.

Your shadow on the dust,

Strength, and a cry,

Delight, despair, mistrust,–

All these am I.

Dawn, and the far hills thrust

To a far sky.

Living, I had no skill

To stay your tread,

Now all that was my will

Silence has said.

We are one for good and ill

Since I am dead.

The Hearer

"SING of the things we know and love."

But the singer made reply,

"There are greater lands to tell you of

And stars to steer you by."

So he sang of worlds austere and strange,

Of seas so wildly wide

That only the journeying swan might range

The marches of the tide.

Men heard the thunder and the rain,

The tempest in his song,

They turned to their hearth fires again

And thought the night too long.

And only one man dared to hear

The deeds that singer told;

Against the stars he swung his spear

And died ere he was old.

The Wood Carver's Wife

The Wood Carver's Wife

|

JEAN MARCHANT, the wood-carver. DORETTE, his wife. LOUIS DE LOTBINIERE. SHAGONAS, an Indian lad. |

The scene is a log-built room. There is a door; and a narrow window, both open. Outside can be seen fields of ripe corn, a palisade, and the corner of a loopholed block-house; beyond is the forest; all is silent and deserted in the sun.

The walls of the room are hung with skins, and here and there with things Jean has carved,–masks, two crucifixes, pipes, a panel showing a faun dancing to the piping of an Indian girl; there are guns also, rods and nets, a long French spade, and a shelf with a few books.

The bare floor is strewn with fine wood-shavings. Jean is carving a Pieta for the new church, in high relief on panels of red cedar wood. Opposite him, facing the door, is Dorette, in a rough chair covered with a fur rug; she is sitting to him for the face of the Madonna. In the doorway sits Shagonas, mending a snare.

The Wood Carver's Wife

| Jean. (singing) |

Hard in the frost and the snow, The cedar must have known In his red, deep-fibred heart, A hundred winters ago, I should love and carve you so. And the knowledge must have beat From his root to his height like the mid-March heat When the wild geese cry from the cloud and the sleet, And the black-birch buds are grown. Then, were you then a part Of the vast slow life of the tree? Did you rise with the sap of his spring? Did you stoop like a star to his boughs? Did you nest in his soul and sing, A silver thrush in a shadowy house, As now, beloved, to me? |

| Dorette. | Not I. I have not sung. |

| Jean. |

The sight of you Sings to the eyes. A little lower down,– Lean but a little lower that fair head, The head of Mary o'er her murdered Christ, The head I kiss in darkness all night long,– Lord! and the delicate hollow of the cheek Defeats the tool. There's no blade fine enough, Unless a strand of cobweb steeled in frost, Or Time's own graver. |

| Dorette. | Hush. I'll not grow old. |

| Jean. | Grow old? I shall grow old along with you. |

| Dorette. |

Together? No, old age is solitary. A little stretching out of hands, a little |

|

Breathing on ashes, and even regret is gone. I tell you, I have seen old people here As not in Picardy. The milk-dry woman Crouching above her death-fire in the snow, The old man biting on a salted skin,– Their patience and the forest–O, I fear Age more than anything. | |

| Jean. |

You are yet too young, Beloved, for my Mary. |

| Dorette. | What do I lack? |

| Jean. |

Why, the cold barren look on nothingness, The grief that cannot weep, for if it could It would be less grief. The inconsolable Dumb apprehension, the doubt that asks for ever |

|

"Is it so?" of Love and hears the answer "Yea," For ever. . . I would grieve you if I could To make my Mary perfect. | |

| Dorette. |

You are hard. You love your cold woods more than loveliness Of look and touch. |

| Jean. |

Why, only as Lord God Might love the delicate dust He made you from, You and great trees, rivers and clouds, the plain Of ripened grasses running into flowers, And all that breathes in the world. There, you have moved! |

| Dorette. |

I only moved a little way to look. You have carved Our Lady's hair in Indian braids. |

| Jean. | Why not? |

| Dorette. |

And laid the Lord on cedar boughs, Wrapping His body in a beaded skin. |

| Jean. |

Why not? He would have walked in our New France Greatly as there, and died for these as well. |

| Dorette. | He is half-Indian. The Intendant will not like it. |

| Jean. |

The Intendant will not see in the dark church. Old Father Peter has a new lace cope, And even his dark-skinned servers will go fine. |

| Dorette. | Ah, the dark people! How I fear them too. |

| Shagonas. |

The lady should not fear. Their hearts are open Even as Shagonas' heart. Shagonas knows Only the ways of stream and wood a little, |

|

And whence to bring the lady snake-root, whence White waterlilies, whence sweet sassafras, And berries in the moon of Falling Leaves. | |

| Dorette. | Not you, Shagonas. I've no fear of you. |

| Shagonas. |

The young dog-foxes running in the fern, The bittern and the arrow-dropping kite, The tall deer with five summers on his head,– These were Shagonas' brothers. Now he comes With broidered nut-bags and a little snare To catch a musk-rat for the lady's sake. Is it well made? |

| Jean. |

Well made and strong, Shagonas, You sleek wolf apt to catch the herd-dog's bark. |

|

The musk-rat ate our pansies out of France And vexed the lady. | |

| Shagonas. |

She must not be vexed. Shagonas dreamed the lady had two shadows. If but the following darkness touches her, Or strikes at her, Shagonas will strike too. So! |

| Dorette. | O, the knife, the knife! |

| Jean. |

Put up, Shagonas. We love it not, the steel in a red hand, Who have seen too much. But what did the boy mean? Beloved, how you cried! |

| Dorette. |

It was the sunlight On the bare blade. I did not guess he wore it. |

| Jean. |

They always have a claw beneath the pelt. I know them well. |

| Dorette. |

When do you go to see The place preparing for your altar-piece? |

| Jean. |

Why, any hour. But I can't leave her yet. Look, how the long hand grows from grain to flesh! Did not the bosom lift? Here at her throat's The beating of a vein. O, if she came From her imprisoning dead cedar wood,– 'Gemma decens, rosa recens, Castitatis lilium,'– You, or the Mother of God? I do not know. I should have two breathing lilies in my room, Two queens, two heavenly roses, O, donum Dei! And yet . . . the face, the face! |

|

Beautiful. But there's no despair in her. That makes despair in me. Look you my girl, Suffer it with her. Think. She only knows The dead weight of the Saviour on her knees As it were a little child's. She's woman. There Is her dead heaven, her babe, her God, her all, Unrisen. The grave yet holds Him. Why, you weep. | |

| Dorette. | I am tired and cold. |

| Jean. |

Well, . . Rest you, little heart. I would not have you greater. Dry your tears. She has dried hers long ago. |

| Dorette. |

I have sat too long. Will you go now to the church? |

| Jean. | Yes, yes, and see |

|

The shrine prepared to put my Lady in. You or the Virgin Mother? You, I think. They'll see you there between the candle flames A hundred years. The lads will worship you And maids with innocent eyes will wonder at you. Your beauty will lift many souls to God. Come, boy. | |

| Shagonas. |

The lady must not be afraid Of any shadow. |

| Jean. | Fare you well, my rose. |

Jean kisses her, takes his sword and broad hat, and goes out, followed by Shagonas. Dorette watches them through the open door as they cross the cornfields towards the blockhouse. When they are out of sight she shuts the door, crosses the room, and kneels before the Pieta, her face hidden in her hands.

| Dorette. |

If you have lain in the night And felt the old tears run In their channels worn on the heart, Pity me, Mary. If you have dreaded the light And turned from the warmth of the sun Like a blind child groping apart, Pity me, Mary. If you have risen from sleep To the shadow of death, and the moon White as one slain for your sake, Pity me, Mary. If you have longed for the deep Close dark in the fulness of noon When the eyes of the forest awake, Pity me, Mary. O, you who went folded in wings Of Godhead, the maiden of God, First star of the morning He made, Pity me, Mary. |

|

No bird of the meadow that sings, No bud that shines up from the sod But pierces me too with its blade. Pity me, Mary. Ah Christ! but will she pity, being pure? You also, yet you pitied. Have compassion. You stilled the wild seas at Gennesaret. Stretch out Your hand and still me. I am torn With tempest, and the deep goes over me. He does not stir. He is dead. O, Louis, Louis! |

There is a soft knocking at the door, but she does not hear. She remains motionless before the Virgin. The door opens, De Lotbiniere enters and shuts it behind him. Seeing her, he uncovers, steals across the room and kneels beside her. Presently she lifts her head and looks him in the face.

| Dorette. | Louis! |

| De L. | O loveliest, join me to your prayer. |

| Dorette. | Louis! |

| De L. |

I too will kneel to Christ and weep That anything so beautiful as love Should have such sorrow on it. |

| Dorette. |

O my dear, I think I knew. But you are mad to come here, Here in broad day. |

| De L. |

I am growing tired of darkness, Dark hours, dark deeds, and little darkling ways, A dirty smoke across the flame of love. I had rather meet your Jeannot face to face With sunshine and clean air. Clean hands, clean heart, They would be his. He's welcome. Does he know? |

| Dorette. | You have not kissed me yet. |

| De L. |

Come to my heart. Now answer me. |

| Dorette. |

The boy Shagonas knows, Not yet my husband. |

| De L. | I almost wish he knew. . . |

| Dorette. |

O, Louis, Louis, if you're in haste for that, Content you. He will learn it very soon. The sharp-tongued grasses that I trod towards you Will whisper him, the winds will tell him, Here, The dews will lie at noontime to betray me, The dawn come out of hour, the dark boughs sigh, There, there the foul thing passed. |

| De L. | O, my Dorette! |

| Dorette. |

That's right. I'll stand and let you kneel to me. Will you kneel gladly? |

| De L. | As I would to her, |

| God's Mother, looking earthward with your face. | |

| Dorette. |

There's not a chisel-stroke he used to brand My likeness there, but casts me farther out From God's forgiveness. |

| De L. |

Alas, my pretty dove. You make me hate myself, my love, my choice That so hath caged you, for you flew so cheerly Between the kind leaves and the little clouds. Gold were your feathers and your wings of silver, And now you feel the mire. |

| Dorette. |

Nay, you have loosed me A flight above the stars. God pity us. We were not made for sin. I love you, Louis. |

| De L. | Why, so I came to hear. |

| Dorette. | You are in haste? |

| De L. |

So bound to my great cousin the Intendant I may not breathe without his lordship's leave Nor tie my shoe without a grant for it. That's right, you smile. You look less angel so, But match me better. I have so much time As the old priest here uses for a pater, No more, no less. |

| Dorette. | But that's enough for love. |

| De L. |

Why, love's timed by the heart beat or the slow Century's half. I have no thought but you, No care, no pride, no hope, no anything. I am not myself but you. My very flesh Has taken your tender likeness on. I see, |

|

Speak, breathe, hear, hunger but as you, Dorette. | |

| Dorette. |

I smiled upon you once, Out in the forest when you talked to me. It seemed no sin among the idle leaves. But here the very windows are sealed up With watchfulness, the doorsill seems aware Who lately crossed it. Louis, I cannot smile. I fear for you, beloved. Will you go? |

| De L. |

What, go so soon? I have scarcely looked at you, Nor touched your hair, nor lifted your sweet hands. My chalice has gone drained of you its wine These three days. Love, I cannot leave you yet. |

| Dorette. | But if he comes. . . . |

| De L. |

When will you to the forest, My dear wild dove? I saw red lilies there Burning in sun-bleached grass, and gentians spread Beside a little pool, less blue than he, The great kingfisher poised on the dead bough. Black squirrels chirred against the quarrelling jays, There came a flight of emerald hummingbirds, While through the wind-swayed walls of reed and vine Laced the quick dragonflies. Sweet, will you come? |

| Dorette. |

I am yours, my heart, wherever I may be. Let it content you. |

| De L. | I am not content. |

She leaves him, goes to the Pieta, and standing before it, speaks.

| Dorette. | O Mother, tell him I cannot go. |

| De L. | Dorette. |

| Dorette. | O Mother, hold me fast against his voice. |

| De L. | Dorette. |

| Dorette. |

O Mother, hide me from his eyes. Build from your sorrowing hands a little ark Where that storm-driven bird, my soul, may rest Till all its heaviness is overpast. Where will that be? In the grave? I think not there. Though my slight bones had lain for centuries Bound over with the prisoning forest roots, And had no other feasting than the rain, And known no other music than the wind, I should yet go climbing upward every spring, |

|

When the whitethroat came and burgeoning grains put out | |

| De L. | I heard none. |

| Dorette. |

It was like The sound of a stretched bow this side the river. Beyond the fields. It had a sound of death. |

| De L. |

Loveliest, what frights you? Life is all for us. The fulness and fruition of the year Are on our side, deep rose and darkening grape Are with us, and the strong bird fledged to fly Forgetful of the nest. In those deep woods I found white flowers beside a little stream |

|

With three waxed petals round a core of gold. | |

| Dorette. |

If you owe me any favour, any grace, Of a promise I once kept, I pray you go. |

| De L. | Are you tired of loving me? |

| Dorette. |

I tired? O Christ! I would lay my body for your feet to walk on, And make a carpet of my hair for you, Be the unsensed wood, the stone, the dust you trod, So that you trod safety. |

| De L. |

Dear, I'll go, But kiss me first. |

| Dorette. |

O Louis, I will seal you With a charm of sevenfold kisses against wrong, Here, here, and here, on hands, cheeks, lips, and head. When first I saw you, back in Amiens, Go riding with the great folk past our door, I thought that head a king's. |

| De L. |

Sweet, losing you I should go unkinged for ever, since my kingdom Rests but in this. |

| Dorette. |

You need not fear to lose me, Save as the strong tree loses the dead leaf Or the full tide one star. Though I should die Soon, and be set behind you like a song Heard once between the midnight and the dawn, |

|

And then forgotten, yet all I was, looked, said, | |

| De L. | First love, and last. |

| Dorette. |

And last. . . and last. . . . Go now. O Christ, too late. |

| De L. | Too late? |

| Dorette. |

They are coming upward from the river, Jean and his Indian boy. |

| De L. | So soon returned? |

| Dorette. | He is walking very fast. I think he knows. |

| De L. | Does he, at last? |

| Dorette. |

Perhaps Shagonas told him, Perhaps the dumb earth lightened into speech, As often times to flowers, or the blank air Took colour in our likeness. . . Why, you wait! O, I am going mad. Have you no limbs, No breath, no natural motion? Would you bide Thus, thus the loosening rock, the falling tree, Fingering a sword? |

| De L. |

Is your Jean not so much? Let him find me here beside you. |

| Dorette. |

If he does I shall go mad indeed. Have I no claim? Have you no pity for me? Is your love Of such a bitter substance that my tears |

|

Can wring no answer from it, nor my hands | |

| De L. | There, lest my heart break. There, poor child, I'll go! |

| Dorette. | Now? Now? |

| De L. |

Now, now. Why, you will make me laugh At these so tender terrors. I will slip Into the berried elder-brake that throws Shade on your sill, and wait till he's within, And the door shut. |

| Dorette. | Go, go. |

De Lotbiniere slips from the door which he leaves open and hides in the thicket which has thrown leaf shadows upon it through the afternoon. Dorette again kneels before the Pieta.

| Dorette. |

Keep open door, O Saviour, of your mercy. Blot him out In soft leaf-shadows like a little death. Shut thou his eyes with webs, his breath with buds, Prison his hands with branches. Strew Thou me Dust on the wind to blind them so they see not, Nor hear . . . . . . Ah! |

Jean is heard singing as he approaches the house.

| Jean. (singing) |

Three kings rode to Bethlehem By the sand and the foam. Three kings rode to Bethlehem. Only two rode home. O, he hath stayed to watch her face And make his prayer thereto, |

|

And to lay down for his soul's grace |

As his song ends, Jean reaches the door and stands within it, gazing at Dorette, who remains before the Pieta. Presently he enters the room, his gaze still upon her.

| Jean. | Do you pray there to yourself? |

| Dorette. | Rather to God. |

| Jean. |

Why, that's a better prayer. You should not pray to yourself. You are too tender, You irised bubble of the clay, to bear The weight of worship. Prayer must not be made To the weak dust the wind cards presently About the world. Why, even your shadow, she, Madonna of the reddening cedar wood, Hath but a troubled momentary power, A doubtful consolation, and a look As though the wind would rend her and the fire Eat to swift ash. No comfort there for sinners. But you're no sinner, need no comforting Other than mine,–as this, and this, and this. |

| Dorette. | You hurt me. |

| Jean. |

I? What, hurt you with a kiss? Shall I go kiss her so? |

| Dorette. | It were a sin. |

| Jean. |

Here is too much of sin and sin and sin. Go, get you to that chair. |

| Dorette. |

Why do you look So strangely on me? |

| Jean. | Is my look so strange? |

| Dorette. |

Yea, sure, as if you found me dead but now And saw my face. |

| Jean. |

I see a kind of death there. Go, sit you in your chair. |

| Dorette. | Where is Shagonas? |

| Jean. | Lingering to shoot at crows with his great bow |

|

More fit for war. He has fledged an arrow thrice | |

| Dorette. |

Jean, not now. I am sick. I am weary. |

| Jean. |

Do you pray to me? You should not. You're Our Lady. You will taste The year-long incense and the holy heat Of candles. They will hail you mystic rose, The tower of ivory, the golden house, Sea-star and vase of honour. Sit you there. |

| Dorette. | I cannot. |

| Jean. | Go. |

| Dorette. | You are very harsh with me. |

| Jean. |

'Tis you are hard to please. I kiss; you tremble, I speak; you are in tears. |

| Dorette. | Where is Shagonas? |

| Jean. | Without, without. |

| Dorette. | I have an errand for him. |

| Jean. |

He will come soon . . . Fie, what a withered look, How your heart beats. You are fevered. Sit, Dorette. Lift your face to the light,–a little forward,– So, now,–and dream you hold across your knees What's dearest of your world, and slain for you That blood may wash out sin. |

| Dorette. | O, Christ! |

| Jean. |

Of course. Who else but Christ? That suits me. Hold your peace. |

While they are speaking, Dorette has seated herself again in the chair facing towards the door, upon which the lightly-stirred shadows of elder leaves come and go. Jean takes up his tools.

| Jean. |

'Tis a fine blade, this one. Do you remember? I sold its fellow when we were in France To buy you a ring. |

| Dorette. | I had forgotten. |

| Jean. |

Turn Your face this way. Look towards me, not the door. What see you? There is only sun outside, Harsh elder drops, ripe fields and ripening hours, |

|

Soft birth of wings among the woven shadows, | |

| Dorette. | Shagonas . . . where? |

| Jean. | What do you say? Are you sick? You speak so low. |

| Dorette. | O, sick of heart! Jean, Jean, I cannot bear it. |

| Jean. |

If you move more, I will bind you to the chair As the Indians bind a prisoner to the stake Lest they miss one shuddering nerve, one eyelids droop Before the lifting fires, . . . Your pardon, wife. Was I so fierce? There's fire in me to-day |

|

Would close a burning grip on the whole earth | |

|

Was worshipful, just, and mighty, His great place | |

| Dorette. | This heat. . . I am dying. |

| Jean. |

What is it you say? If I should gash this sacred brow I smoothe Would you break blood? If I should pierce your heart Would she of the sevenfold sorrows leap and cry? I cannot part you. O the grief of it, That Mary should sit there with you, and you Climb heaven with her. I am grown old with grief In a short hour. To work, to work,–your face. |

| Dorette. | Call, call Shagonas. |

| Jean. |

Has he the art to heal you? What do you fear? I would not have you fear. I would have you like poor Mary here, who passed Beyond it, of a Friday. |

| Dorette. | O my heart. |

| Jean. |

Broken like mine? And so you had a heart, As well as those round limbs, those prosperous lips, The bloom of bosom and hair? 0, he hath stayed,– O, he hath stayed to watch her face And make his prayer thereto, And to lay down for her soul's grace His life beneath her shoe,– Why, I have changed the song. What's come to it? An ill song for the Mother o' God to hear. Well, well, your pardon. Keep your face to me. |

| Dorette. | Pity, O Saviour. |

| Jean. |

I am saving you, Your soul alive, a brand in a great burning Here in my breast. I saw where you will sit Years in the little forest-scented church, And lives like peaceful waves will break in foam Of praise before you. Then I turned me home. I saw–I saw–O, God, the chisel slipt And I have scarred you! I will heal the wound, Thus, thus. Be still. I am saving you. Now, Shagonas! |

Jean has crossed the room, caught her to her feet, and stands holding her and her face to the door. Suddenly the note of a drawn bowstring is heard outside, something flashes past, there is a silence. Then among the shaken shadows of elder leaves on the door is seen for one moment the shadow of a man, erect, with tossed arms, and pierced through with a long arrow. Comes the sound of a fall, or broken branches. Then again silence, and the shadows of the leaves are still. Jean seats Dorette again in the chair, where she remains quite motionless; he returns to the Pieta and takes his tools.

| Jean. |

Your face again. Why, now you are fulfilled. You will make my Mary perfect yet, your eyes Now, now the barren houses of despair, Of the passion that is none, of dread that feels No dread for ever, of love that has no love, Of death in all but death. O beautiful, Stretched, stamped and imaged in the mask of death, The crown of such sweet life! Your looks, your ways, Your touches, your slow smiles, your delicate mirth, All leading up to this! And his, the high |

|

Clear laughter on the threshold of renown, |

Shagonas enters, carrying De Lotbiniere's sword, which, obeying a gesture of Jean's, he lays across the knees of Dorette. She looks down upon it as though blind.

| Jean. |

Your only fruit Destruction and the severing steel, the heat Of tears unshed, the ache of day and day Monotonous in want, inevitable, The dry-rot of the soul. Have you no words? |

| Dorette. | He said–he said there were flowers in the forest, |

|

White flowers by a blue pool, Our Lady's colours. | |

| Shagonas. |

There is no fear In the forest shadows now for the fair lady. |

| Jean. |

Fear's slain with that it fed on. To your wilds, You wolf that watched the flock. I will wait here with her,– Stay, hearing a certain crying from the ground, The faint innumerable mouthing leaves, The clamour of the grass, the expectant thunder Of a berry's fall. Go you, go you. But first |

|

Turn me her head a little to the shoulder Now, now my Virgin's perfect. Quick, my tools! |

All is silent save for the tinkle of a little church bell ringing for vespers, and a faint sound of chanting.

| Jean. |

Salve, Regina, Mater misericordiae, Vita, dulcedo, et spes nostra, salve. O clemens, O pia, O dulcis Virgo Maria. Will the light hold until they come for me? |

(Curtain)

Out of England

Merlin's Isle

O, I went down to Merlin's Isle,

And when that I had found it,

I kneeled me down a little while

And praised the peace that bound it.

There were no seas around it,

But the full tide of turf in flood

To the rim of the berried hawthorn wood,

And a dew-pond where the dear stars stood

Too deep for me to sound it.

O, I went down to Merlin's Isle

And there I soon did learn-a,

The winds they did implore me,

How sweet two beech-brown eyes may smile

Among the maiden fern-a.

My poor heart took a turn-a.

In a warm wind the whitebeam foam

Ran quick along the silvering loam,

And I was young and far from home,

As you may well discern-a

O, I went home from Merlin's Isle,

My dear was there before me.

In the moonshine by the shepherd's stile

A kind of grief came o'er me.

The winds they did implore me,

"And come," they said, but I said "Nay,

For the honey star hath closed the day,

And love that borrowed my soul away,

Sweet love shall now restore me."

Sheep

LIKE the slow thunder of long seas on the height

Where God has set no sea,

Voices of folded sheep in the quiet of night

Came on the wind to me.

Like the low murmur of full tide on a beach

Where tide shall never roll,

They sent their mournful, inarticulate speech

Heavily on my soul.

Past is my sorrow, the night past, and the morn

Bright on her golden sills.

Only the hill-fold voices drowsily scorn

The comfort of the hills.

"When I was a Tall Lad"

WHEN I was a tall lad with money in my hand,

I'd pots and pans a plenty, and friends about the land.

I'd golden roads in sunshine and silver roads in rain,

And a little gray donkey and a girl out of Spain.

Now I am an old man with rings in my ears,

All too sad for laughter, all too wise for tears.

And the Spanish girl has left me, and the money's coming slow

And the little gray donkey he was lamed long ago.

When I get to heaven where tinkers may be seen,

I'll wear a yellow kerchief and a coat of velveteen,

And out beyond the shining streets I'll take the road again

With a little gray donkey and a girl out of Spain.

Going Home

UNDER the young moon's slender shield

With the wind's cool lips on mine,

I went home from the Rabitty Field

As the clocks were striking nine.

The yews were dark in the level light,

The thorn-trees dropped with gold,

And a partridge called where the dew was white

In the grass on the edge of the fold.

O, had your hand been in my hand

As the long chalk-road I trod,

The green hills of the lovely land

Had seemed the hills of God.

The Fortune Seeker

HOLLYHOCKS slant in the wind,

Gallantly blowing,

Crinkled and purfled and lined,

Thank God for their growing.

Their burden is only of bees,

Banded and brown,

But she, O, she's

The worth of my world on her head for a crown.

How can she step it so freely, so lightly,

Her head like a star on a stem showing whitely,

Mow can she carry her

Wealth with that innocent air?

I'm going to marry her, marry her, marry her,

Just for the wealth of her hair.

Larkspurs as deep as a pool,

Lilies like ladies,

Silvered and silked where the cool

Elder tree shade is,

These are the queens of the sun,

Splendid and sweet,

But she, my one

Flower's without price from her head to her feet.

How can she go by the lanes and the ditches,

Her little proud head unbowed by its riches?

How can she carry her

Fortune so light in the air?

I'm going to marry her, marry her, marry her,

Just for the gold of her hair.

Canada To England

GREAT names of thy great captains gone before

Beat with our blood, who have that blood of thee:

Raleigh and Grenville, Wolfe, and all the free,

Fine souls who dared to front a world in war;

Such only may outreach the envious years,

Where feebler crowns and fainter stars remove,

Nurtured in one remembrance and one love,

Too high for passion and too stern for tears.

O little isle our fathers held for home,

Not, not alone thy standards and thy hosts

Lead where thy sons shall follow, Mother Land.

Quick as the north wind, ardent as the foam,

Behold, behold the invulnerable ghosts

Of all past greatnesses about thee stand.

Marching Men

UNDER the level winter sky

I saw a thousand Christs go by.

They sang an idle song and free

As they went up to calvary.

Careless of eye and coarse of lip,

They marched in holiest fellowship.

That heaven might heal the world, they gave

Their earth-born dreams to deck the grave.

With souls unpurged and steadfast breath

They supped the sacrament of death.

And for each one, far off, apart,

Seven swords have rent a woman's heart.

When It is Finished

WHEN it is finished, Father, and we set

The war-stained buckler and the bright blade by,

Bid us remember then what bloody sweat,

What thorns, what agony

Purchased our wreaths of harvest and ripe ears,

Whose empty hands, whose empty hearts, whose tears

Ransomed the days to be.

We leave them to Thee, Father, we've no price,

No utmost treasure of the seas and lands,

No words, no deeds, to pay their sacrifice.

Only while England stands,

Their pearl, their pride, their altar, not their grave,

Bid us remember in what days they gave

All that mankind may give

That we might live.

For All Prisoners and Captives

OVER the English trees and the English meadows

Twilight is falling clear,

But my heart walks far in the homeless winds and the shadows

For those who are not here.

Youth and pleasure and peace and the strong flesh clothing

The freeman's soul, they gave;

Beauty they gave for a scar and honour for loathing

And life for a living grave.

But not of the least they gave was the English, mellow

Sunlight on beech leaves spread,

And the Squirrel flickering earthward to find his fellow

Where the chestnut husks lie dead.

And not of the least they lost was the calm star climbing

Over the elm tree's height,

And the heron high in the mists, and the hoar frost riming

The ivy leaves at night.

Night and the early moon, and the dead leaves burning,

And England secure and free

By the price of uncounted heartbreaks toward her turning

Across her kindred sea.

Night, and the smell of the earth, and the blue reek lifting

Straight as a prayer from the plain.

Loose them, O Sleep, to the sun and the beech leaves drifting

And the stubble fields again!

Night, and the robins still, and the long smoke folding,

The fallow on either hand,

And the spirits of those who sorrow afar, beholding

In dreams their native land.

English Flowers

YE have been bought

With an immortal price,

O, windflowers quick as thought

Of love in solitude,

And daffodils, the year's young sacrifice

When summer's on the wood.

In no forgetful hour

Through the wind-trodden gold,

I follow the springs dower

Of leaf and sallow spray,

Men gave the flower of life that I might hold

Blossom and leaf to-day.

Again

JUST to live under green leaves and see them

Just to lie under low stars and watch them wane,

Just to sleep by a kind heart and know it loving

Again–

Just to wake on a sunny day and the wind blowing,

Just to walk on a bare road in the bright rain,–

These, O God, and the night, and the moon showing

Again–

"THE WOOD CARVER'S WIFE AND LATER POEMS, " BY MARJORIE L. C. PICKTHALL, WITH DECORATIONS BY J. E. H. MACDONALD, A.R.C.A., HAS BEEN PRODUCED FOR MCCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED, BY WARWICK BROS. & RUTTER, LIMITED, TORONTO.