TIBETAN WOMAN AND SON

| With the Tibetans in Tent and Temple |

| NARRATIVE OF FOUR YEARS' RESIDENCE ON THE TIBETAN BORDER, AND OF A JOURNEY INTO THE FAR INTERIOR |

| BY SUSIE CARSON RIJNHART, M.D. |

Third Edition |

|

Fleming H. Revell Company Chicago, New York & Toronto Publishers of Evangelical Literature MCMI |

COPYRIGHT, 1901,

BY FLEMING H.

REVELL COMPANY

TO THE MEMORY OF MY

HUSBAND, WHOSE HEART

AND LIFE WERE GIVEN

TO THE TIBETANS, THIS

VOLUME IS DEDICATED

PREFACE

In the following pages I have attempted to narrate briefly the events of four years' residence and travel among the Tibetans (1895-1899). The work does not aim at literary finish, for it has been written under the stress of many public engagements. It is sent forth in response to requests and suggestions received from friends in all parts of the United States and Canada.

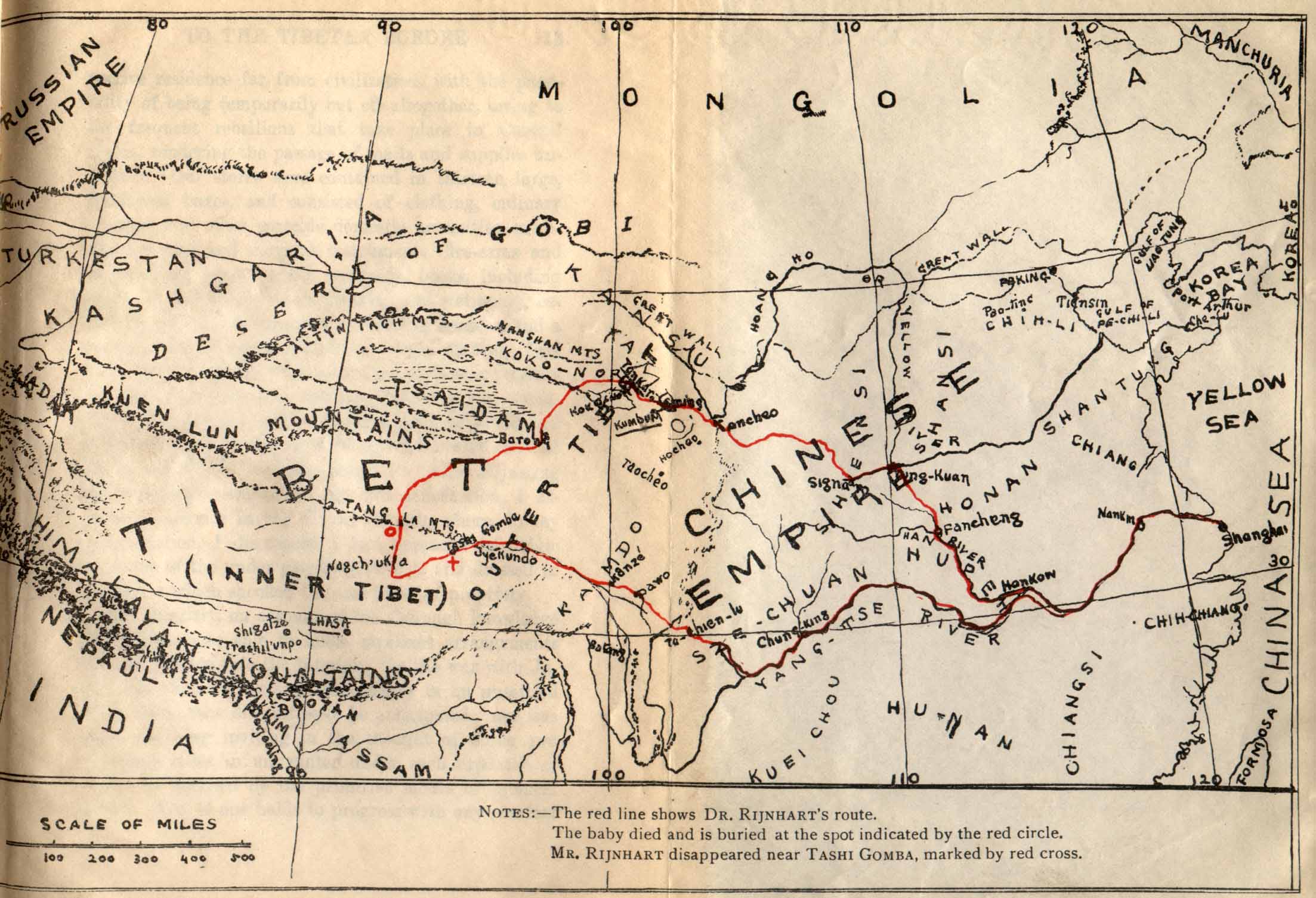

If I may succeed in perpetuating and deepening the widespread interest in the evangelization of Tibet, already aroused by the press and platform accounts of the missionary pioneering herein described, I shall be glad. To this end I have incorporated in the narrative as many data concerning the customs, beliefs and social conditions of the Tibetans as space would allow. My close contact with the people during four years has enabled me to speak with confidence on these points, even when I have found myself differing from great travelers who, because of their brief sojourn and rapid progress, necessarily received some false impressions. The map accompanying the book shows the route of the last journey undertaken in 1898 by my husband, myself and our little son, and of which I am the sole survivor. Leaving Tankar on the northwestern frontier of Chinese or Outer Tibet, crossing the Ts'aidam Desert, the Kuenlun and Dang La Mountains, we entered the Lhasa district of Inner Tibet, reaching Nagch'uk'a, a town about one hundred and fifty miles from the capital. In describing this journey, such portions of Mr. Rijnhart's diary as I was able to preserve, and also his accurate geographical notes, have been of inestimable value to me.

My thanks are due to Rev. Mr. Upcraft, Baptist missionary at Ya Cheo, China, for photographs from which some of the illustrations were made. And I am especially grateful to Prof. Charles T. Paul, of Hiram College, who placed at my disposal the fruits of his many years' study of Tibetiana, and rendered me invaluable assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

SUSIE C. RIJNHART.

Chatham, Ontario, Canada.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | TO THE TIBETAN BORDER. – Mission in a Buddhist Lamasery – Preparation for the Journey – Across China – Impressions by the Way | 9 |

| II. | AMONG THE LAMAS. – Arrival at Lusar – Strange Lama Ceremonies – Medical Work – Our Tibetan Teacher – First Experience with Robber Nomads | 27 |

| III. | A MOHAMMEDAN REBELLION. – Moslem Sects – Beginnings of the Struggle – Our Acquaintance with the Abbot – Refuge in the Lamasery – The Doctrine of Reincarnation | 50 |

| IV. | WITH THE WOUNDED. – Refugees at Sining – Our Isolation at Kumbum – The Siege of Shen-Ch'un – To the Battlefield – A Ride for Life – Rout of the Mohammedans | 68 |

| V. | MISSIONS AND MASSACRES. – Bible School at Lusar – Mohammedan Revolt at Sining – Terrible Slaughter by Imperial Soldiers – The Fall of Topa – Peace at Last | 86 |

| VI. | THE LAMASERY OF KUMBUM. – Tibetan Lamaseries – Legend of Tsong K'aba – Origin of Kumbum – The Gold Tiled Temple and Sacred Tree – Nocturnal Devotions and Worship of the Butter God | 102 |

| VII. | A BUDDHIST SAINT. – Mina Fuyeh's Abode – His Previous Incarnations – Mahatmas – Conversations on Christianity – Jambula – Behind the Scenes | 120 |

| VIII. | OUR REMOVAL TO TANKAR. – Tankar and Surroundings – A New Opportunity – Ani and Doma – The Lhasa Officials – Drunken Lamas – Visit of Captain Wellby | 133 |

| IX. | DISTINGUISHED VISITORS. – Mr. Rijnhart's Absence – Our House is Robbed – Visit of Dr. Sven Hedin – Tsanga Fuyeh – Medical Work among Nomads – Birth of our Little Son | 155 |

| X. | AMONG THE TANGUTS OF THE KOKO-NOR. – Tangut Customs – Journeys to the Koko-Nor – Nomadic Tent-Life – A Glimpse of the Blue Sea – Robbers – Distributing Gospels | 170 |

| XI. | TOWARD THE TIBETAN CAPITAL. – Lhasa the Home of the Dalai Lama – Need of Pioneer Work in Inner Tibet – Our Preparations for the Journey | 191 |

| XII. | FAREWELL TO TANKAR. – Leaving Faithful Friends – Our Caravan Moves Off – Through the Grass Country to the Desert – Two Mongol Guides | 205 |

| XIII. | IN THE TS'AIDAM. – The Ts'aidam and its People – Polyandry and Cruelty to the Aged – The Dzassak of Barong – Celebration of Baby's Birthday – Missionary Prospects | 219 |

| XIV. | UNPOPULATED DISTRICTS. – Crossing the Kuenlun Mountains – "Buddha's Cauldron" – Marshes and Sand Hills – Dead Yak Strew the Trail – Ford of the Shuga Gol – Our Guides Desert Us – Snow Storm on the Koko-Shilis – We Meet a Caravan – The Beginning of Sorrows | 232 |

| XV. | DARKNESS. – Nearing the Dang Las – Death of Our Little Son – The Lone Grave Under the Boulder | 245 |

| XVI. | BEYOND THE DANG LA. – Accosted by Official Spies – Our Escape – The Natives Buy Copies of the Scriptures – Our Escort to the Ponbo's Tent | 254 |

| XVII. | NAGCH'UK'A. – Government of Nagch'uk'a – Under Official Surveillance – Dealings with the Ponbo Ch'enpo – We are Ordered to Return to China – Our Decision | 265 |

| XVIII. | ON THE CARAVAN ROAD. – The Start from Nagch'uk'a with New Guides – Farewell to our Last Friend – Rahim Leaves for Ladak – Fording the Shak Chu Torrent – Reading the Gospels – A Day of Memories | 275 |

| XIX. | ATTACKED BY MOUNTAIN ROBBERS. – We Cross the Tsa Chu – Suspicious Visitors – A Shower of Bullets and Boulders – Loss of Our Animals – Our Guides Disappear – The Dread Night by the River | 289 |

| XX. | OUR LAST DAYS TOGETHER. – The Robbers' Ambush – The Worst Ford of all – Footmarks and a False Hope – A Deserted Camp – The Bed under the Snow – Mr. Rijnhart Goes to Native Tents for Aid, never to Return | 302 |

| XXI. | LOST AND ALONE. – Waiting and Watching – Conviction of Mr. Rijnhart's Fate – Refuge among Strange Tibetans – Their Cruel Treatment – The Start for Jyékundo for Official Aid | 312 |

| XXII. | WICKED TIBETAN GUIDES. – The Apa and the Murder of Dutreuil de Rhins – Conference with a Chief – New Guides, Treacherous and Corrupt – The Night Camp in the Marsh – We are Taken for Robbers – A Lamasery Fair | 325 |

| XXIII. | A FRIENDLY CHINAMAN. – A Protector at Last – I Receive a Passport from the Abbot of Rashi Gomba – A Lama Guide – Battle with Fierce Dogs – Arrival at Jyékundo – No Official Aid | 342 |

| XXIV. | MORE ROBBERS. – From Jyékundo to Kansa – Difficulties with Ula – At the Home of the Gimbi – Corrupt Lamas – Attacked by Drunken Robbers – Deliverance | 357 |

| XXV. | SAFE AT LAST. – The Approach to Ta-Chien-Lu – My Pony becomes Exhausted – Long Marches with Blistered Feet – Chinese Conception of Europeans – Among Friends Once More – Conclusion | 377 |

| GLOSSARY | 399 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| TIBETAN WOMAN AND SON | Frontispiece |

| MAP SHOWING DR. RIJNHART'S JOURNEY | 12 |

| BORDER TYPES | 22 |

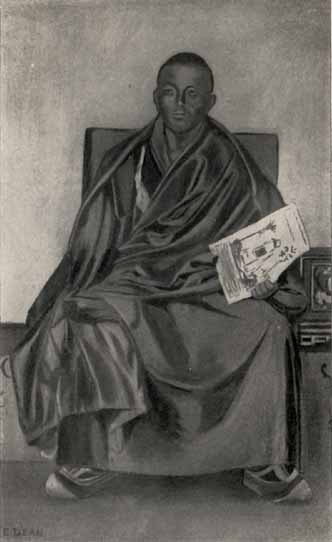

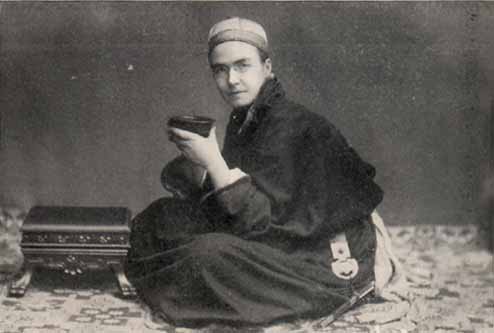

| TIBETAN BUDDHIST LAYMAN | 109 |

| MINA FUYEH | 120 |

| TANGUT ROBBERS | 188 |

| A TIBETAN TRAVELER | 214 |

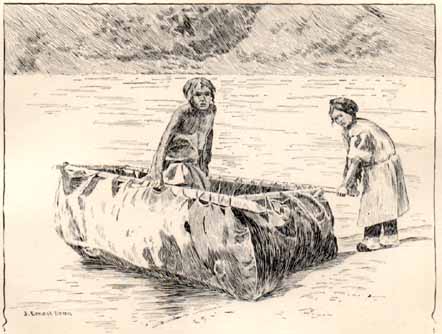

| TIBETAN CORACLE | 262 |

| CROSSING A ROPE BRIDGE | 282 |

| PETRUS RIJNHART | 302 |

| THE AUTHOR IN TIBETAN COSTUME | 312 |

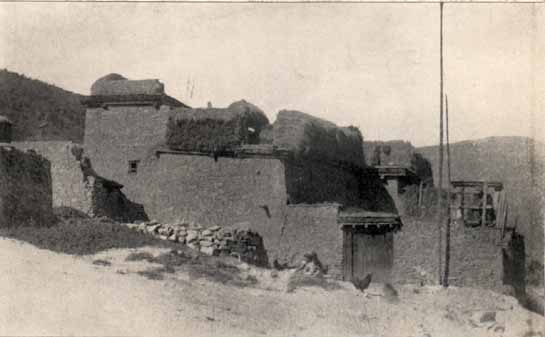

| A TIBETAN HOUSE | 326 |

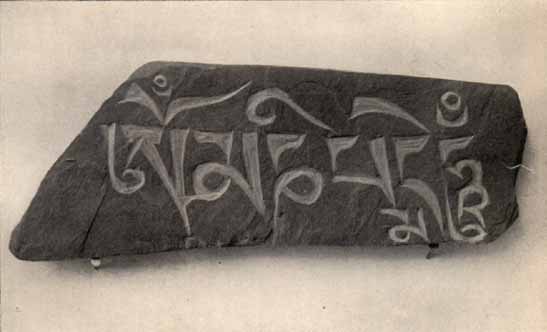

| MANI STONE WITH INSCRIBED PRAYER | 346 |

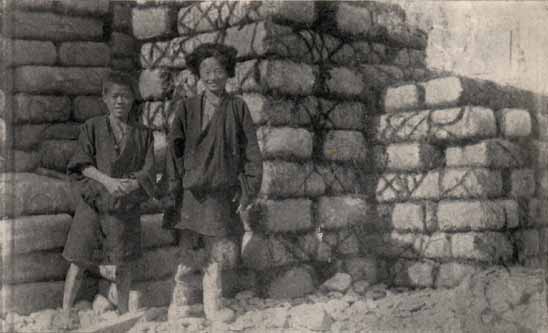

| A WALL OF TEA BALES | 362 |

WITH THE TIBETANS

CHAPTER I

TO THE TIBETAN BORDER

Mission in a Buddhist Lamasery – Preparation for the Journey – Across China – Impressions by the Way.

On the slopes of two hills in the province of Amdo, on the extreme northwestern Chino-Tibetan frontier, nestles the great lamasery of Kumbum, famed among the devotees of Buddha as one of the holiest spots on Asiatic soil. As a center of Buddhist learning and worship it is known in the remote parts of China, Manchuria, Mongolia, and in all the Tibetan territories, even to the foot of the Himalayas, and is estimated to be second in rank only to Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. It is the seclusive residence of some four thousand lamas and, at festive seasons, the goal of pilgrimages from all Buddhist countries contiguous to Tibet. Desiring to carry on missionary work among the Tibetans we left America in the autumn of 1894, having Kumbum as our point of destination. We expected to make our home and establish a medical station at Lusar, a village which may be called the secular part of the lamasery, where the lamas do their trading, and which is only about five minutes' walk from the lamasery proper. The considerations which led us to select Lusar as a basis of operations, besides its proximity to the lamasery, were as follows: My husband, Mr. Petrus Rijnhart, about three years previous had conceived the idea of entering Tibet for missionary purposes, from the Chinese side. From the experiences of Huc and Gabet, the Lazarist fathers, who, following a route through Tartary and China, had gained free access into the forbidden land, he was convinced that the antipathy to foreign intrusion everywhere manifested in the vigilantly guarded passes of the Himalayan frontier south and west did not exist to any extent on the northeastern border between Outer Tibet and China. In this he was right. Crossing the Chinese Empire, he had reached Lusar in 1892, had resided for ten months in the vicinity of the lamasery, had been well received by the priests, who called him a "white lama from the West," and had labored diligently to make known the Gospel. His work had consisted principally of private conversations with the lamas, and of short journeys among the nomads of the surrounding country, preaching and teaching, and wielding what little medical knowledge he possessed in the treatment of the sick. Among his patients were people of high and low degree, lamas from the great monastery, Tibetan and Mongol chiefs of the Koko-nor tribes, officials, merchants, shepherds, and even robbers. The interest with which his ministrations were received gave him great encouragement and deepened the intense longing he had already conceived for the evangelization of the Tibetans. Many with whom he came in contact had never seen a European nor heard the name of Christ. Some of the lamas said the Christian doctrine was too good to be true; others inquired why, if the doctrine were true, the Christians had waited "so many moons" before sending them the glad tidings. During one of his itinerating journeys "a living buddha" with his train of dignitaries came to the tent, having heard, as he said, that a man with a white face had come, and, sitting at the feet of the white stranger, the Buddhist teacher listened with rapt attention to the wonderful story of the world's Saviour. During his sojourn no official, either Chinese or Tibetan, asked for his passport, or questioned him as to his intentions of penetrating to the interior. Thus under circumstances unexpectedly favorable, surrounded by good will and hospitality, and free from that prejudice and espionage with which foreigners approaching the Tibetan border are usually regarded, he had had ample opportunity of studying the life, needs and disposition of the people, and his knowledge gave us assurance of the reception that awaited us at the lamasery village. Again, Lusar was advantageous from a topographical standpoint, being situated near the juncture of several important highways; one leading to China, another to Mongolia, and still another, the great caravan route, leading to Lhasa. Here we could easily receive supplies, and would be likely to come in contact with the people on a large scale, owing to the amount of traffic that passes along the great roads. Also, the surrounding country being inhabited by a cosmopolitan population comprising Mongols, Chinese, Tibetans, and a few Turkestani Mohammedans, it was a good place in which to become conversant with the languages we should require, looking forward as we were to a life-long sojourn in the regions of Central Asia. We left America for our distant field without any human guarantee of support, for we were not sent out by any missionary society. Although, through Mr. Rijnhart's lectures in Holland, the United States and Canada, considerable interest had been aroused and many friends won to the cause of Tibetan missions, yet our visible resources were limited at best. We went forth, however, with a conviction which amounted to absolute trust that God would fulfil His promise to those who "seek first the Kingdom," and continue to supply us with all things necessary for carrying on the work to which He had called us. From the outset we felt that we were "thrust forth" specially for pioneer work, and although anticipating difficulties and sacrifices we were filled with joy at the prospect of sowing precious seed on new ground.

Our party, consisting of Mr. Rijnhart, his fellow-worker, Mr. William Neil Ferguson, and myself, sailing from the Pacific Coast, had decided to follow substantially the same route across China which Mr. Rijnhart had taken on his former journey. From Shanghai up the Yangtse to Hankow we would go by steamer; thence by house-boat up the Han as far as Fancheng, situated about four hundred miles up the river. The remainder of the journey would be completed overland by cart and mule. We had endeavored, before leaving America, to equip ourselves as well as possible, not only against the long journey, but also, in view of our pros-

[Map showing Dr. Rijnhart's journey]

pective residence far from civilization, with the possibility of being temporarily cut off altogether, owing to the frequent rebellions that take place in Central China, rendering the passage of mails and supplies uncertain. Our stores were contained in thirteen large, ponderous boxes, and consisted of clothing, culinary utensils, and other portable domestic necessities, medicines, dental and surgical instruments, fire-arms and ammunition, photographic materials, books, including copies of the Scriptures in Tibetan, and stationery, besides compasses, thermometers, a sewing machine and a bicycle. In Shanghai we added drugs, clothing, food for the river journey, Chinese brazen oil lamps, trinkets for bartering, and other articles. Knowing the advantage of traveling in native costume, each of us donned a Chinese suit. It was my first experience with oriental attire, and I shall not soon forget it. After adjusting the unwieldy garments to my own satisfaction, I attended a service in the Union Church, where, to my consternation, I discovered I had appeared in public with one of the under garments outside and dressed in a manner which shocked Chinese ideas of propriety.

Mr. Rijnhart, on account of his thorough knowledge of Chinese, was able to make excellent arrangements for our passage into the interior. As the war with Japan was then raging and the country in an unsettled state, there were difficulties to be anticipated; nor was there anything inviting in the thought of doing two thousand miles in midwinter under such exposure as would be entailed by the primitive modes of oriental travel. Yet, if one holds to progress with any comfort worthy the name, there are reasons for making the journey during the hibernating period of the greater portion of the inhabitants of China, namely, the verminous!

Our first stage up the Yangtse was made in a steamer manned by English officers and a Chinese crew. There was a sense of security, which afterwards we sadly lacked, in the feeling that the great river was but an arm of the gentle Pacific that laved our native shores, stretched far inland as if to assure us of protection. Our first stopping-place was the city of Hankow, an important commercial centre situated at the confluence of the Han and Yangtse rivers, and, following the sinuosities of the Yangtse, distant about eight hundred and fifty miles from the seaboard. The city was full of stir on our arrival. The people were intensely excited over the war, and signs of military activity were on every hand. The spacious harbor at the mouth of the Han presented the appearance of a forest of masts in which all the ships of Tarshish and of the world had congregated in one dense fleet. They were chiefly house-boats and cargo junks that usually ply up and down the river, but conspicuous among them were the high-pooped transports, their decks crowded with blue and red jacketed soldiers on their way to the scene of action.

We took passage for Fancheng in the inevitable house-boat, a long, clumsy-looking scow divided into three compartments; the captain's cabin at the stern, inhabited by himself, his wife and little child; another long cabin for the passengers, situated amidships and separated from the former by a movable partition; and a space at the bow where the crew discharged the functions of eating, sleeping and working. Under each compartment was a hold for the belongings of its occupants. On the rare occasions when the winds were favorable the sails were sufficient to propel the awkward craft; otherwise she was pulled along by the sturdy trackers on the shore. In deep water the captain steered by means of a prodigious rudder; in the shallows he managed with a long, stout bamboo pole. This mode of traveling was not without its amenities. The weather being fine, and the scenery along the river banks charming, we frequently disembarked and went afoot, and occasioned no little commotion as we passed through the villages, a foreign woman being an object of especial interest. Crowding around, the people would handle my clothing and ply me with questions, evincing astonishment at the size of my feet.

The villagers were mostly of the agricultural class, and appeared to be very industrious. The door-yards were tidy, as were also the farms, every available foot of land being cultivated. Everything about the houses betokened an air of freedom, even the pigs and chickens being allowed to go in and out at will. Signs of religious life were not wanting. In one village we came across an old temple mostly in ruins, in the one remaining corner of which were ten idols, some incense bowls and sticks, while near by lay the huge bell, silent and long since fallen from its lofty place. In the evening the people flocked to the old ruin to worship amid the sound of firecrackers and the beating of a huge gong by the attendant priest, and as the weird sounds were carried afar and re-echoed in the cold, still evening air there was about the whole scene a touching picturesqueness not unmingled with solemnity. Christmas day found us still on the house-boat, and with it came many pleasant memories of that glad, festive season in the homeland, and many reflections concerning China's teeming millions to whom the Christ of Bethlehem was still a stranger.

On January 7 we reached Fancheng, none the worse for our river journey. A hearty welcome was given us by the resident Scandinavian missionaries, Mr. and Mrs. Matson, Mr. and Mrs. Woolin, and Mr. Shequist, whom we found engaged in a most valuable work. Besides preaching, they conducted a boys' school, and at the time of our visit were erecting a school for girls. Our stay in Fancheng was brief, just long enough to get through the unenviable and seemingly endless preliminaries to an overland journey by cart. The hiring of the carts was itself no little matter even with the assistance of our Scandinavian friends, but finally the piao was signed, by which we secured two carters, with two large carts and a small one, to take us to Signan. By the word "cart" this Chinese vehicle is but faintly described. It consists of a clumsy, bulky frame set on a single axle, innocent of springs, its two wheels furnished with tires several inches in width and in thickness. The frame is covered by an awning of matting to shelter the traveler and his baggage from the heat and rain. The smaller carts, constructed on the same plan, are generally painted and have a cloth covering with windows in the sides. These carts are drawn in China by mules or horses, in Mongolia by camels or oxen. In many of the principal roads deep grooves have been worn by the constant passing of the great wheels, and, the length of the axle differing in the various districts, the grooves are not equidistant on all roads, so that it occasionally happens that at certain junctures all axles have to be changed. At Tung Kuan, for instance, a town situated at the meeting-place of the provinces of Shensi, Shansi and Honan, this operation is necessary.

On January 11 we were ready to start. We had taken the precaution to furnish our cart with a straw mattress, some pillows and comforters, to provide against the jolting which we knew awaited us. Our boxes being already in position, after Scripture reading with the missionaries our little caravan moved off. Two of the missionaries accompanied us outside the city gates to bid us God-speed, and it was only after we had parted ways with them that we realized we had actually set out on the most difficult part of our journey across the Celestial Empire. The road from the start was very uneven, a fall of two feet being not uncommon. I received a severe bump on the head, and experienced so many changes of position and came so frequently and emphatically into collision with various portions of the cart as to have remembered that springs are not a luxury of cart travel in China.

Carters are supposed to make a certain stage each day, and inns are found at the end of each stage for the accommodation of travelers. In order to cover the required distance we were frequently on the way in the middle of the night, and even though traveling from long before daylight until dusk we were not always able to reach an inn. At such times one must either sleep in the cart or put up in a farmhouse. Even the regular inns are by no means inviting. We first stopped in one of these thirty-five miles from Fancheng. It was a flimsy structure, with great crevices gaping in the walls, in which were rude lattice windows with paper panes; the ceilings were composed of bamboo poles nailed across the rafters, from which cobwebs hung in profusion; the sleeping-room had no floor, and the bed was as hard as boards could make it, springless of course, and destitute of covers. But one welcomes any variation from the tedium of a Chinese cart journey, and after the jolting of the first day can rest even in a Chinese inn.

One night, having failed to make the required stage, we sought shelter in a native hut on a hillside and slept on the k'ang, an article of furniture which no traveler in Western China soon forgets. The k'ang is a sort of elevation built across one end of the room, resembling a hollow platform, the top sometimes covered with flat stones. It serves the purpose of all the principal articles of furniture in an occidental house – chairs, stove, bed and table. It is warmed by a fire placed in the box, and, when the surface is moderately heated, one may recline with comfort; but on this night the k'ang was so hot that we soon became uncomfortable, being almost roasted on one side and frozen on the other. We were finally obliged to get up and rake out all the fire, and at last fell asleep from sheer exhaustion and despair.

A foreigner's passport in China enables him to pass free of charge all customs, and also the ferries that are usually found, in lieu of bridges, plying across all the rivers of considerable size which cut the great highways. The ferry which took us across one large river was crowded with people going to market on the other side, paying their passage, some with vegetables, some with cash. The ferryman collected the fee as he sat on the ground in front of his straw wigwam. After congratulating ourselves on the safe passage of the river, one of the wheels of our heaviest cart sank fast in the sand, and two extra mules had to be hitched on to pull it out.

Our carters were interesting fellows, but their knowledge of Chinese politics, as of things in general, was limited. Referring to the war with Japan, one of them informed us that Li Hung Chang had been made Emperor of China. Some of the people through whose territory we passed had heard nothing of the war, and others said that the Emperor's subjects in France had rebelled!

China is favorable soil for the flourishing of the older cults, Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism standing side by side and being largely intermingled. A Chinaman may with no sense of incongruity profess all these beliefs at once. He would not appreciate Dr. Martin's statement that logically the three are irreconcilable, Taoism being materialism, Buddhism idealism, and Confucianism essentially ethical. Like the state, he makes a unity of them by swallowing a portion of each.1 As we journeyed onward the monuments to this complex religious life increased in abundance. Here, passing through a city, we beheld the "gates of virtue," immense, carved stone arches spanning the streets, and erected to the memory of some sage, or pious person; there, on the hillsides, reared to some Buddhist saint, "stones of merit," on the tops of which little bells are fixed so that the wind causes them to ring out the praises of the great man long since passed away. Caves also, formerly the abodes of hermits, were pointed out to us, and colossal statues of the Buddha hewn from the solid rock, gazing down upon us with an air of sublime and majestic calm, still bearing witness to the zeal of the early Buddhist bhikshus who wandered forth from India to make known "the Teacher of Nirvana and the Law." In Western China nearly every farm has its contiguous graveyard in which may be seen the tables whereon the people place their offerings to the spirits of the dead. As we reflected on the part that the great non-Christian religions have played in China, and on the deep-grained, age-long impress they have made upon her people, the magnitude of our mission to a people not less religious, more superstitious, and enchained in a denser ignorance and a more blighting system, grew upon us in unwonted realization. Yet our faith did not waver. In much weakness we were going to undertake a stupendous task – not in our own strength but in His who when He commanded His disciples to "go and make disciples of all the nations," also promised "Lo, I am with you all the days, even unto the end of the world."

Crossing a stone bridge of stately and antique architecture, we reached the city of Signan, the old imperial capital of China, and at present the capital of the province of Shensi. Here our carters made arrangements with other carters to take us on to Lancheo, they themselves returning to Fancheng. Signan is the most important trade centre of the northern interior, the home of the Emperor of a former dynasty, a city of heavy walls, paved streets, stately palaces and handsome governmental buildings. It is the site of the famous Nestorian tablet which bears record of Christian missions in China as early as the seventh century of our era. The surrounding country, relieved by undulating hills, is particularly charming; great roads branch off in all directions, two of the main ones leading to Kansu. The merchants of Signan carry on trade in all the surrounding provinces, and even in Mongolia, Tibet and Turkestan.

With our new carters we set out once more, although unfortunately for us it was the Chinese New Year, and consequently very difficult to buy food, as during that festive season all the shops are closed for days together. However, we did not wish to tarry at Signan. Bright, sunny days and cloudless skies, with nothing more adverse than an occasional wind or dust storm, such as are common in Western China, seemed to us to be favorable conditions for pressing on.

One of the important functions in connection with the celebration of the New Year is the lantern festival observed on the fifteenth of the first moon. Arriving at a large city one night, intending to put up at an inn in the suburbs, we found ourselves in the midst of the festival. The long street was lined on either side with lighted lanterns of exquisite and varied designs. Crowds of people surged up and down, and all was life, movement and jubilation – a weird scene, the moon shining down in icy calmness upon it all. Our horses becoming frightened at the tumult and glare of light and at the passing of a long string of camels with ringing bells, almost upset our carts in their frantic efforts to hide somewhere. We thus attracted attention even against our will, and it was with difficulty that we ourselves avoided being mobbed. Relieved indeed we felt when we reached a miserable inn, which in our thoughts was transformed almost into a palace, as it afforded us a haven of rest and safety from that brilliantly lighted festive street.

It was a happy day for us when we reached Lancheo, the capital of Kansu, for we had looked forward to a few days' respite in that city. Shortly after we had taken up quarters in an inn, Mr. Mason, of the China Inland Mission, came with a message from Mr. and Mrs. Redfern, extending to us a pressing invitation to stop at their home. He had brought the mission cart to transport us, and we soon found ourselves enjoying the hospitality of the missionaries. At Lancheo we formed the acquaintance of Mr. Wu, a Chinaman who had studied eight years in America, making a specialty of telegraphy. He had been up in the new province superintending the laying of telegraph lines, and in com-

BORDER TYPES.

pany with his companions in Lancheo, was now returning to Peking. The day before we had arrived he had entertained Messrs. Redfern and Mason at a feast in a restaurant, where, of course, according to Chinese etiquette, ladies could not be present. Wishing to entertain us all, he prepared a second feast, which was served in the sitting-room of the mission house, so that the ladies might with propriety attend. Everything, including dishes, was brought from the restaurant. While on the road we had had considerable practice in using chopsticks, and we thoroughly enjoyed the food, which was dainty to the palate and artistic in appearance. Knowing our views regarding the use of wine as a beverage, Mr. Wu had provided delicious tea in elegantly decorated covered china cups, and sweatmeats by way of compensation. Chinese politeness ruled the feast, each one helping with his own chopsticks another to whom he wished to show courtesy. Among the many delicacies there was a sucking pig cut into little pieces and cooked in a perfect manner, also bamboo sprouts, lily tubers and other dishes of which at the time we did not even know the names. Western people are mistaken who imagine that the only items in the Chinese menu are rice and rats. As cooks the Chinese vie even with the French, and some of the most delicious meals we partook of while abroad were prepared by the Chinese. In acknowledgment of Mr. Wu's hospitality, Mrs. Redfern in turn prepared a feast for him; it was a proper English dinner, with several kinds of dessert; yet we must confess, in point of delicacy the Chinese feast was superior.

After a few days, Mr. Rijnhart and Mr. Ferguson went up the big cart road to Sining with the luggage, while I remained behind with Mr. and Mrs. Redfern, until Mr. Rijnhart, who would go on from Sining to Lusar to rent a house, should return for me. I shall ever gratefully remember the intervening pleasant days spent at Lancheo and the kindness received from the missionaries. Within a few days Mr. Rijnhart came back and announced that he had been successful in leasing a house, but that considerable repairs would be necessary. We left the next day for Sining, Mr. Rijnhart riding on a horse and I on a donkey, both of which had been generously loaned us by Mr. Ridley, of the China Inland Mission of Sining. The two animals had been companions for so long that wherever the horse led the donkey followed, a fact which I appreciated on this, my first donkey ride, as it solved for me the anticipated difficulty of guiding one of these proverbially stubborn animals along steep and difficult paths. Not far from Lancheo we arrived at the branch of the Great Wall which crosses the Yellow River, and found the ancient structure in a very dilapidated condition, broken by great gaps and much worn by the rains of centuries. It was not more than five feet in height, and however effective a defence it once may have been against the incursions of Turks, Mongols and Manchus, it would not be a serious obstacle before a modern army. There are two roads from Lancheo to Sining; one for cart, the other for mule travel. The carts make the journey by the "big road" in ten days; by the "short road" over the mountains, the one we had chosen, mules arrive in half the time.

The Kansu country presents an elevation varying, according to Rockhill's itinerary, from four thousand to nine thousand feet. Hilly ridges run in several directions, sheltering from the cold winds the fruitful valleys, remarkable for their luxuriant production of grapes, melons, peaches, apricots and all kinds of grain. Around the city of Lancheo tobacco is grown in large quantities and forms the basis of the city's industry. Part of our route lay beside the Yellow River, and for a time, also, we followed the rushing waters of the Hsi-ho, one of its tributaries. We saw Mohammedan merchants coming down the river with their cargoes of vegetable oil, destined for the Lancheo market, on rude floats made of inflated cowhides lashed together. How exciting it was to see the skillful boatmen guide one of these heavily laden floats around a sharp bend in the river, where the water boiled and foamed over the shallows. Just when it seemed certain that destruction against some sharp ledge awaited the craft, by a dexterous thrust it would be sent out into the current and carried past the point of danger amid the shouts of all the spectators.

Passing over the ruins of many villages which had been devastated in the Mohammedan rebellion of 1861-74, we came eventually to a narrow gorge of considerable historical importance. Ascending the road that skirts the precipice, we saw the river boiling below, beating itself into foaming rage in protest against its sudden limitation. It was in this pass that the Mohammedans held the Chinese army at bay during that bloody period forever memorable to the inhabitants of Kansu, and where again, in 1895, they placed themselves thousands strong, and sought to repeat the tactic. Little did we think, as we passed along the river edge on a beautiful sunny day, beneath an over-arching sky of cloudless blue, and amid the peaceful solitude of the mountains, broken only by the patter of the animals' hoofs and the low monotonous thud of plunging torrents, that this very place was within a few weeks to be again the scene of military tumult, filled with legions of infuriated, bloodthirsty rebels; and we dreamed even less that the massing of the Mohammedans here to check the advance of the Chinese army, was to be the providential dispensation which would prevent them from sweeping down on Lusar and Kumbum, where they would have found us an easy prey.

The people of Kansu we found to be gentle and obliging. They quite sustained their reputation of being less disagreeable than the natives of other provinces, for they treated us with the utmost kindness and did all in their power to expedite our journey. On the fifth day after our departure from Lancheo the walls of Sining loomed in the distance, and we were within the gates in time for afternoon tea at the China Inland Mission Home, where we were cordially welcomed by Mr. and Mrs. Ridley and Mr. Hall. Fifty li westward lay Lusar, where our house had already been secured, and the glittering turrets of the great Buddhist lamasery of Kumbum.

CHAPTER II

AMONG THE LAMAS

Arrival at Lusar – Strange Lama Ceremonies – Medical Work – Our Tibetan Teacher – First Experience With Robber Nomads.

The western portion of the province of Kansu, variously denominated by geographers as part of Chinese or Outer Tibet, is known to the Tibetans as Amdo, and the inhabitants are called Amdo-wa. According to Chinese ethnographers the foreign population of Amdo may be divided into two great classes, the T'u-fan, or "agricultural barbarians," who have a large admixture of Chinese blood, and the Si-fan, or "western barbarians," who are of pure Tibetan stock. The Si-fan live, for the most part, a nomadic life and are organized into a number of bands under hereditary chiefs responsible to the Chinese at Sining, to whom they pay tribute. Chinese authors further say that the present mixed population of Amdo is the progeny of many distinct aboriginal tribes, but there are some elements of it that must be accounted for by later immigrations. Westward from Sining the road leads through a highly cultivated plateau; the farms are watered by a perfect system of artificial irrigation, bearing evidence of the industry and skill of the peasants. The houses in the villages are all built of mud and have flat roofs. On the road one meets groups of merchants, partly Chinese, but bearing a strong resemblance to the Turk and distinguished by a headdress which seems to be a cross between a Chinese cap and a Moslem turban. These are Mohammedans going down to trade in Sining. Next comes creeping along a small caravan of camel-mounted Mongolians or Tibetans, clad in their ugly sheepskin gowns and big fur caps, on their way to see the Amban of Sining, or perhaps going to Eastern Mongolia or Pekin; or one may meet a procession of swarthy faced Tibetan pilgrims returning single file, with slow and stately tread, from some act of worship at Kumbum, to their homes in the valleys north of Sining. The entire western portion of Kansu, so far as its inhabitants are concerned, marks the transition between a purely Chinese population and a foreign people, the Chinese predominating in the larger centers but the villages and encampments being made up largely of foreign or mongrel inhabitants.

Mr. Rijnhart had left me at Sining and had gone on to Lusar to complete the preparation of our house; but I had become impatient, not having too much confidence in masculine ability to set a house in order in a way altogether pleasing to a woman, so I rode up to Lusar with Mr. Hall. Half a day's journey brought us within sight of the hills that surround Kumbum, and as we approached we could see some of the lamas attending to their horses or gathering fuel. But the strangest sight of all was that of Mr. Rijnhart and Mr. Ferguson in European clothing; so accustomed had our eyes become to oriental attire that they appeared more grotesque even than any of the fantastically arrayed travelers we had met on the road. Assisted by some native carpenters, they had been very busy at the house, but when I arrived I found everything in confusion, just as I had anticipated. Yet I was thankful that our long journey had been completed, not a single accident worthy the name having happened to us since we left the Pacific Coast of America six months before.

Lusar boasts of a single main street with mud-brick flat-roofed buildings on either side, and, at the time of our arrival, contained about one thousand inhabitants, evenly divided between Mohammedans and Chinese, with a sprinkling of Tibetans and Mongols. These different peoples could be distinguished by their general appearance as well as by their speech. The Mongol, with his broad, flat, good-natured countenance and short-cut hair, clad in his long sheepskin robe, with his matchlock thrown over his shoulder, could not be mistaken as he waddled through the street followed by his wife a few paces behind him; the pure Tibetan, likewise robed in sheepskin, heralded his nationality by the sword he carried in his belt. To mistake a Chinaman was, of course, beyond question, while the Mohammedan of Turkestani origin could be recognized by his aquiline nose, slender face and straggling beard or moustache. Being the trading station of the Kumbum lamasery Lusar is visited by merchants from China, Mongolia and various parts of Tibet. Especially during the great religious festivals held from time to time at the lamasery a brisk trade is done in altar-lamps, charm-boxes, idols, prayer-wheels and the other paraphernalia of Buddhist worship. Near the village is a remnant of an old wall which evidently at some time had been used as a rampart of defence. In Huc and Gabet's narrative no mention is made of Lusar for the reason that it probably did not exist when these travelers passed that way, the business of the Kumbum lamasery being done formerly at Shen-ch'un, a few miles distant from Kumbum.

The Chinese carpenters made characteristically slow progress with our house. The noise that accompanied the work was at times almost deafening, the workmen all shouting at once when anything urgent was to be done. The house, situated at the foot of a hill, the façade pointing toward the main street, was a substantial mud-brick structure with flat roof, built entirely according to Chinese ideas of architecture, and after we had the premises put in order the disposition of the apartments was about as follows: The main gate led into an outer courtyard, walled but not roofed; from the outer court a dark, narrow passage led to the central or inner courtyard, around which the rooms were arranged on all sides. In one corner was the kitchen, and diagonally opposite to it a storeroom, and in another corner the stable, while along the sides nearest the entrance were the two guest-rooms, one for men and the other for women, the latter containing a cupboard for drugs. The guest-rooms we destined for the reception of visitors coming for medical treatment or to inquire about spiritual matters. The walls were hung with colored Bible pictures which did us good service in suggesting topics for religious conversation. Many of the pictures represented scenes in the life of Christ and aroused the natives to the asking of questions which opened for us golden opportunities to read the New Testament and to tell them more fully the Gospel story. The furniture was plain and scant, a large table four feet square, a few high, straight-backed and very uncomfortable chairs, and the indispensable k'ang. Opposite the guest-rooms were our dining-room, study and bedroom. On the two remaining sides were Mr. Ferguson's apartments, our Chinese servant's bedroom and a sitting-room where we all met for prayer, Bible study and conversation. Access to the flat roof of the house could be had by means of a ladder, and oftentimes when the weather was fine we repaired thither to take our constitutional, or to sit basking in the sun. Behind the house on the hill we afterwards prepared quite a large piece of garden, in which we raised several kinds of vegetables from seeds sent to us by a friend in Canada. Our housekeeping was reduced to simplicity. Han-kia, our Chinese "boy," aged about twenty-two years, soon learned under my tuition to prepare many kinds of food in English or American style, and twice a week he regaled us with m'ien. Having no oven in our stove, we extemporized one out of a paraffin tin, in which we could roast meat and bake cookies. Altogether we did not fare badly at Lusar; in the market we could buy mutton, eggs, milk, vegetables, flour and rice. Custom soon introduced us to our new surroundings, and when the carpenters had finished, we were, taking it all in all, as happy in our far-away, isolated home as we possibly could have been in America.

Not long after our arrival we were visited by Mr. and Mrs. Ridley and their little baby Dora. They had come up for the purpose of recuperating their health among the hills, and during their sojourn we witnessed the interesting ceremony of burnt offerings celebrated near the Kumbum lamasery. Crowds of Chinese and Tibetans, men, women and children, had congregated to see the procession of lamas issue from their temple, and, discovering that some foreigners were among the throng, they turned their attention to us, almost overwhelming us with their friendly curiosity. It seemed at times that we would be crushed to death. Being surrounded we could not return home, and we were obliged to devise at once some means of protection. Inviting the native women to sit down beside us we were soon in the midst of a large group squatting tailor-fashion about us, serving as an effective bulwark, preventing the crowd from surging in upon us. Mrs. Ridley drew the women into an interesting conversation, taxed to the utmost all the while to keep them from laying violent hands on her baby.

The Tibetan women were to us an especial object of interest, conspicuous in their long, bright colored dresses fastened around the waist by green or red sashes, their clumsy top-boots and their elaborate head dress. The hair was done up in a number of small plaits which hung down the back and were fastened together with wide strips of gay colored cloth, or by a heavy band of pasteboard or felt covered with silver ornaments, shells and beads, and on top of it all was a hat with white fur brim and red tassels hanging from the pointed crown. From the ears were pendant great rings, to which were attached strings of beads hanging in long loops across the breast. The Chinese women with no hats, their black hair shining with linseed water, their common blue dresses and deformed feet, were not nearly so attractive as their neighbors, the Tibetans.

Presently the sound of horns, cymbals and gongs announced the approach of the procession, and all in confusion rushed off to see the sight. Hundreds of lamas, clad in their flowing robes, issued with solemn tread from the lamasery, some of them carrying large, irregular wooden frames painted red, blue and yellow, and huge bundles of straw. The frames were set up in an open place, the straw arranged around them, and the ceremony of burnt offerings was ready to begin. The lamas fired off guns, chanted some unintelligible incantations, blew deafening blasts on their gigantic horns, and then set fire to the straw. The frames were soon reduced to ashes, and the purpose of the ceremony, we learned, was to ward off the demons of famine, disease and war.

As soon as the people found out that we were prepared to treat their ailments and dispense medicines they came to us quite freely. The Chinese were the first to approach us, but soon the Tibetans came, even the lamas, and it was not long before we had as much medical and resultant guest-room work as we could attend to. As it is impossible to get a crowd of Tibetans to listen to a discourse, our evangelistic work consisted chiefly in conversing upon Christianity with the people who came to see us, and from the very beginning we were able to interest them in the teachings of the New Testament. The Tibetans themselves having no medical science worthy the name, the treatment given by the native doctors generally means an increase of agony to the sufferer. For headache large sticking plasters are applied to the patient's head and forehead; for rheumatics often a needle is buried in the arm or shoulder; a tooth is extracted by tying a rope to it and jerking it out, sometimes bringing out a part of the jaw at the same time; a sufferer with stomachache may be subjected to a good pounding, or to the application of a piece of wick soaked in burning butter grease; or if medicine is to be taken internally it will consist probably of a piece of paper on which a prayer is written, rolled up into the form of a pellet, and if this fails to produce the desired effect another pellet is administered, composed of the bones of some pious priest.

Although the natives appear to have great faith in the native doctors, yet they were quick to bestow their patronage upon us. Among the common ailments we were called upon to treat were diphtheria, rheumatism, dyspepsia, besides many forms of skin and eye disease. One morning a woman brought to us her husband, who was suffering from diphtheria, and asked us to give him medicine. After explaining that the disease was very fatal, and that her husband was so ill that he would probably die, adding that we would not be responsible if he died, we gave him what treatment we could, including some medicine to be taken at home. The next morning his wife came to announce that he could not take the medicine. I then offered to go to the house, purposing to clear away some of the membrane and relieve the sufferer, but on our arrival we found that a lama had pasted a notice on the door forbidding anyone to enter because, he said, a devil had taken possession of the house. We were obliged to turn away and our hearts were saddened to hear two days later that the man and also one of his little children had died.

Since it was our intention to work principally among the Tibetans, we at once faced the problem of acquiring the language, although we might have got along with Chinese alone since all the Tibetans on the frontier speak that language as well as their own; but knowing that the Tibetan language would be to us a means of closer communication with the natives, we set about to find a teacher. As the lamas are the sole possessors of Tibetan letters, the great masses of the lay population being unable either to read or write, they were not over pleased with the thought of communicating their sacred language to "foreign devils," and we had great difficulty in persuading any one to teach us. Finally a young, rather good looking lama, named Ishinima,2 consented to give us instruction for a nominal sum, on condition that we would not let it be known, for he seemed very much afraid lest someone might accuse him before the sung kuan, or disciplinarian of the lamasery, of being on too friendly terms with the foreigners; for of course as yet we were looked upon with more or less reserve and perhaps with a little suspicion. Ishinima was of medium height, well built, and favored the Mongolian type rather than the Tibetan, although he always said that he was of the latter parentage. His face was pockmarked, but not devoid of expression, and when he smiled his whole countenance glowed with good humor. He did not belong to the highest class of lamas, yet, not having to do menial work, he was well dressed, wearing the lama's ordinary habit – a sleeveless red jacket, a full skirt girded around the waist, and a long, wide scarf carelessly, yet always in the same manner, thrown about the shoulders. His garments were dirty, but not ragged. The first money he received in payment for his lessons he invested in cloth at Sining, and I made him garments of it on my sewing machine. He told us that the lamas were not allowed to wear sleeves, trousers or socks except upon special occasions, and added that on this point the lamasery had a code of very strict laws, violation of which entailed severe punishment, sometimes even expulsion. Though Ishinima could read the Tibetan character well, we found to our disappointment that he could not explain it at all, so our lessons took a more practical turn, we giving him Chinese words and phrases which he translated for us into Tibetan. He came to teach us every day except Sunday, on which day he always attended the religious service held in the guest-room.

Tibetan belongs, philologically, to the Turanian family of languages. It is essentially monosyllabic, resembling in this respect many of the languages of our North American Indians. The verb system is built up on roots with prefixes and affixes, the syntax is comparatively uninvolved and the idioms clear and expressive. The alphabet, adapted from the Sanskrit by Tou-mi-sam-bho-ta, a noted Tibetan scholar and statesman, about 623 A. D., affords a character simple and easily formed, contrasting strongly with the cumbrous glyphics of the Chinese. There are two principal dialects of the language – Lhasa Tibetan, supposed to be the standard of excellence, and Eastern Tibetan, which varies from it to a considerable degree. The Koko-nor Tibetans, in fact, have great difficulty in understanding the speech of Lhasa traders and lamas. For colloquial purposes we were particularly interested in the Eastern Tibetan, though of course if one desires to read, the Lhasa dialect must be learned, as that is the literary language of the country.

Our professor yielded to none in the matter of uncleanliness, hence we made it our endeavor to instill into his mind some idea of hygiene. After some instruction he learned to use the towel and soap, and though the lamas have a rule not to allow scissors to touch their heads when having their hair cut, he allowed his head to be shaved by the clippers, which were an endless source of wonder and interest to the natives. By degrees he took on an appearance of decency, and began to show some signs of interest in new ideas. Being somewhat of an epicure he went freely into the kitchen, supervising the preparation of the dainties for which he had a preference. He taught our Chinese servant to make oma-ja, a decoction which the Tibetans drink with great relish. The ingredients are implied in the name – a piece of brick-tea is put into a pot of water and allowed to boil a few minutes, then about half as much milk as water is added, and the whole brought to boiling point again. When later we were without a servant, our boy having gone to enlist as a soldier, Ishinima would make the m'ien. Instead of cutting it into strips he would cut it into squares, and add it to water, meat and vegetables, making a palatable and substantial dish. Though we studied hard at our Tibetan and endeavored to understand the people and to communicate with them, we did not make the progress we should have made, the cause of this being that he taught us a mixture of Tibetan and Mongolian, which was to a large extent unintelligible to either people. In this and other things we found him unreliable, and some of his actions bordered on dishonesty.

Soon after we had made his acquaintance, Ishinima invited us to his home in the Kumbum lamasery, and, having set his house in order for our visit, he came to escort us thither. Crossing the ravine which divides Kumbum into two sections, and threading our way along narrow alleys and past rows of whitewashed dwellings, we finally stood before one of the outermost and best houses of the lamasery. The courtyard presented a tidy appearance, and was graced by a flower garden in the center, in which some yellow poppies were in bloom. Several red-robed lamas with bare heads and smiling faces gave us a Mongol welcome, holding out toward us both hands with the palms turned upward, and immediately ushered us through a small room into a still smaller one, of which the k'ang covered the entire floor. Upon the door hung a curtain, laden with the dust and grease of ages. The furniture was that usually found in a lama's home. There was the k'ang table, about ten inches in height, on which were placed some china basins, a brightly-painted tsamba dish, and a wooden plate containing bread fried in oil, none too inviting either by its taste or smell. The walls of the room were adorned with the pictures which we ourselves had given to our host, and which with their western flavor seemed quite out of keeping with the rude interior. During a very pleasant conversation about the great monastery with its revered lamas and sacred traditions, about Lhasa, the home of Buddhist learning, and of the great Dalai Lama, about the doctrines of Christianity, and about the great western world, of which Ishinima knew next to nothing, we drank tea and partook of other refreshments which the latter had prepared with his own hands. According to custom he offered us a large lump of rancid butter, which, had we been as polite as our host, we should have dropped into our cup of tea in lieu of sugar; but knowing Ishinima so well, we refused the dainty morsel, although to have done so under any other circumstances would have been considered little less than insult. He was, moreover, so thoroughly charmed with Mr. Rijnhart's telescope and camera that we might have ignored all Tibetan politeness with impunity.

After tea we were conducted across the courtyard to Ishinima's private chapel, or room containing his household altar and instruments of worship. Upon the altar sat several diminutive but none the less hideous brass and clay idols, representing various Buddhist divinities, before which were burning small butter lamps, also of brass, filled with melted butter, each furnished with a wick and darting up its little flame. Other flat brazen vessels of water, some khatas or "scarfs of ceremony" – narrow strips of veil-like cloth, corresponding in use to the western carte-de-visite – , a few musty-looking tomes of Buddhist literature, completed the equipment of this domestic sanctuary. We found Ishinima withal a most genial host, exercising every art within his grasp to make our visit pleasant; yet we were glad when the time came to return to our own clean and airy dwelling at Lusar, and we left conscious that we had done Ishinima good service in ridding him of a generous share of the vermin in his sacerdotal abode. Our battle with this unwelcome company was to begin when we reached home.

Through our friendship with Ishinima we gained a knowledge of Kumbum and all that pertained to it, which otherwise we might long have sought in vain. Shortly after our visit to his home he accompanied us again to the lamasery to witness an elaborate ceremony on the occasion of the ordination of the priest who was to serve as lamasery doctor. Ishinima having some scruples about appearing publicly as our guide, walked about fifty yards ahead of us, never, however, turning a corner until he assured himself that we were following. Having arrived in the courtyard of the temple where the ceremony was to be held, we took our places, Ishinima standing at some distance opposite us and scarcely taking his eye off us from first to last. The walls of the temple court were hung with all manner of fantastic pictures executed in flaming colors by Chinese artists. In the middle of the enclosure was a long narrow table, similar to those often found on American picnic grounds, on which were placed rows of decorated plates and brazen vessels of various shapes and sizes, containing tsamba, rice, barley, flour, bread, oil and other eatables. These, we learned, were offerings which had been brought to be sacrificed in honor of the new candidate for the position of medical superintendent. A large crowd of spectators had congregated and were gazing with reverent and longing looks upon the feast prepared for the gods, when suddenly a procession of about fifty lamas broke into the courtyard, arrayed in red and yellow robes, each one carrying in his hand a bell. As soon as they had seated themselves on the stone pavement, the mamba fuyeh, or medical buddha, came in and took his place on an elevated wooden throne covered with crimson and yellow cloth. He wore a tall, handsomely embroidered hat and brilliant ceremonial robes, befitting the occasion. The ceremony began by a deafening clatter of discordant bells, each lama vying with the others to produce the most noise from his instrument. The music was followed by the muttering of some cabalistic incantations and the weird chanting of prayers. Immediately in front of the mamba fuyeh was a large urn in the bottom of which a fire was smoldering, sending up its vapory clouds of smoke and incense. At a given signal some of the lamas rose and, each one taking up in a ladle a portion of the delicious viands that stood on the table, walked gravely to the urn and dropped it into the fire as an offering in honor of the new mamba fuyeh, and finally a stream of liquid which we took to be some kind of holy oil was poured in from a little brass pot. Then there were repetitions of the prayers, incantations and bell-ringing, and it was a long time ere the mamba fuyeh was declared duly installed. The position of medical lama is considered one of great importance. The office in the Kumbum lamasery is held for varying periods of time, depending partly on the incumbent's efficiency, but more perhaps on the number of his influential friends.

Like most lamas, Ishinima had many strange tales to tell of the Koko-nor, the blue inland sea, that lies away to the west of Lusar and Kumbum, far up into the grass country. Many an evening he entertained us detailing in reverent tones something of the wealth of legend which tradition and the popular fancy have woven around that body of water. It is known by Tibetans, Mongols and Chinese, each calling it by a different name, but the Mongol name "Koko-nor," meaning "Blue Lake," seems to have gained ascendency. Its religious importance is recognized throughout a large portion of Central Asia. Even the Amban, the Chinese Ambassador or Governor of North-eastern Tibet, who lives at Sining, makes a pilgrimage to it once a year and pays it homage. The immediate effect of Ishinima's representations was to arouse in us an intense desire to visit the lake, to make the acquaintance of the Koko-nor tribes and to ascertain the prospects for missionary work among them. As Ishinima had never seen the lake himself, he seemed overjoyed when we asked him to accompany us. The date for the departure was set in the month of June when the hills had taken on their luxuriant carpeting of green, and all nature seemed to conspire in producing ideal conditions for such an excursion. As W. W. Rockhill, the American traveler, had written about the opposition of the Amban and other Chinese officials to Europeans going into the grass country, all our preparations were very quietly made. We employed a muleteer with four animals, collected stores for the entire journey which, going and returning, we calculated would last about twelve days, and in the highest spirits started off, leaving our home in the care of a servant. Ishinima, perched high on a load consisting of the tent and bale of food, wore a large straw hat with the wide brim of which he carefully concealed his face until we got out of the locality where he was known. Reaching Tankar late in the evening, we pitched our camp outside the gate. Anxious to avoid officials, we arose at daybreak and passed through the town to the west gate, being frequently accosted by men who wanted to drag us before the lao-yeh at the yamen; but we escaped into the grass country, and passed the monastery of Gomba Soma, although every one we met was looked upon as some official who might possibly forbid us to go any further. Ten miles from Gomba Soma, and still a long way from the lake, we camped for breakfast near a bend of the Hsi-ho, or Western River, in a beautiful grassy spot studded with pink flowers. On the other side of the river was spread a charming panorama of rolling hills which in the early morning looked like the grey, slumbering tents of some giant army. Never shall I forget the calm of that beautiful day on the oriental plateau far away from the turmoil of civilization, nor within sight or sound of the rudest encampment or settlement of any kind.

But out of this tranquil environment there was to grow a great unrest. While Ishinima was gathering argols (the Mongolian word for the dried excreta of animals which the nomads use for fuel, and which must be used in fact by all travelers, as these wild regions are bare of wood) our mules broke away from their tether and had soon scampered out of sight. Mr. Ferguson and the muleteer set out in search of the missing animals. All day Mr. Rijnhart and I waited, wondering how both the mules and pursuers fared. We knew nothing definite until Mr. Ferguson's return at eleven o'clock at night, and he could only announce that no trace of the runaway mules had been found, and added, to our horror, that he had become separated from the muleteer and did not know what fate might have befallen him. He might have lost his way somewhere on the dreary plain or among the winding hills, and there was the graver possibility of his having been eaten by wolves or having fallen into the hands of the redoubtable Tangut robbers who lurk in the ravines ready to pounce upon any prey, great or small. Clouds of anxiety hung on Ishinima's dusky face. He could not sleep. Time and time again he went outside the tent, casting his eyes far and wide over the starlit waste, eager to catch any sign of the lost muleteer, but in vain. His anxiety was not without cause, for if anything should have happened to the muleteer he would have been held responsible. A feeling of insecurity pervaded the whole camp, Ishinima having succeeded in persuading us that the Tanguts might swoop down upon us at any moment. The agony and stillness of that awful night, broken only by the subdued sounds of our own voices, the distant howl of a wolf, and the monotonous babble of the Hsi-ho rapids, were not soon forgotten. At daybreak next morning, just as Ishinima was preparing breakfast, two of the missing mules, quite mule-like, returned of their own accord, and soon after, to our great joy, our muleteer came running into camp. The faithful fellow had continued his fruitless search away into the night, and, having lost his way, had crouched down behind a rock to rest till daybreak; he seemed quite compensated for his trouble on finding that two of the mules had come back. One black animal being still astray, Mr. Ferguson went out again on the search. As he did not return after an unaccountably long time, Mr. Rijnhart took the sweep of the horizon with the telescope to see if there were any trace of him, and, after a short absence, came running to the tent shouting, "Get the guns ready! There are six wild Tibetans after Will!" Excitement reigned supreme and every preparation was made to show the enemy our ability and readiness to defend ourselves and our goods if need be. Mr. Ferguson rode well, outstripping his pursuers all but one, a big Tibetan armed with a spear, who followed closely on his track. We knew that Mr. Ferguson was quite capable of looking after himself, as he carried a revolver, and usually the sight of foreign arms of any kind has a salutary effect on these wild nomads. Soon not only Mr. Ferguson but the six Tibetans had reached our tent, and the latter were preparing to help themselves to our possessions when Ishinima remonstrated, informing them that we had foreign guns, whereupon they threw their rude matchlocks and clumsy spears to the ground, sat down beside them, filled their pipes and smoked and chatted in a very friendly manner. Presently another group of Tibetans came galloping toward our tent. They were ten in number, and as they drew near we espied our lost black mule among their animals. These Tibetans were well dressed in garments of various and gorgeous colors. We did not know their intentions, but they kept assuring us in the name of Buddha that they were good men, and if any proof were wanting they triumphantly added that one of their company was a lama. At the same time the predatory instinct began to manifest itself; the newcomers insisted on having first one thing and then another of our belongings, and were only restrained from looting the entire camp when Mr. Rijnhart threatened to shoot if they laid hands on a thing. After some further altercation we gave them some cash for catching our mule – Ishinima gave them a mani, or rosary, of great value, and the entire band rode off. The question now was: should we continue our journey to the Koko-nor or return home? I was ever so grateful when Ishinima declared that the Tibetans who had just left us were Tangut robbers, and that they would most assuredly return presently with reinforcements to attack us, for that announcement led to an immediate decision to turn back. Although later we made the Koko-nor journey with no fear, but with greater experience and knowledge of the grass country and its inhabitants, for the moment the vision of the Blue Lake grew dim, and loading our mules we leaped into our saddles, and were soon galloping toward Tankar, with sweet dreams of the safety and shelter that awaited us in our little home at Lusar.

Deviating a little from the road by which we had come, we arrived at Chang-fang-tai, a Tibetan village nestling on the edge of a small stream. The country hereabout was quite fertile, although in an uncultivated state. Roaming along the bank of the stream, we gathered specimens of ferns, grasses and wild flowers. The inhabitants seemed to be peaceably disposed, coming into our tent and taking tea with us. Here, by the way, I tried my first dish of tsamba, the staple article of diet throughout Tibet, taking the place of bread in other countries, and which I had always imagined must be very delicious from the zest with which Ishinima invariably devoured it. Tsamba is a kind of meal made from parched barley, which, after being thoroughly kneaded with the fingers in a mixture of tea and butter, is taken out in lumps and eaten from the hand. Though Mr. Rijnhart added sugar to make it more palatable, I could not eat it.

In the midst of our enjoyment at this village we heard the first alarming tidings of the terrible rebellion which shortly broke out in full fury among the Mohammedans of Western Kansu. Faint rumblings of the storm had already been heard, but we had not considered the outlook serious. During the day we had noticed clouds of smoke rising in the distance, and these, a Tibetan courier informed us, marked the scene of the beginning of Mohammedan depredations. A column of the rebel fanatics had swept across the North country and fallen upon a Chinese village, killing all the inhabitants, setting fire to the buildings, and leaving nothing but ashes, smoke and charred corpses. Hastily we pulled up our tent, and, though the night was dark, we rode off toward Kumbum, with great difficulty following the trail which wound in and out among the hills, while every dark object became to our excited imagination a crouching Mohammedan ready to dart his merciless spear. A sigh of relief escaped us as we arrived at the gate of Lusar, yet we knew more serious news awaited us as, contrary to custom, the gate was closed and carefully guarded. The old gate-keeper, whom we knew well, opened to let us in, and informed us of the danger that like a dark cloud had fallen on the village since we left. At any moment the Mohammedans were expected to rush in from some neighboring ambush. But amid the gloomy forebodings that for the moment filled our minds, there was a tremor of joy at the thought of our good fortune in returning to Lusar when we did. The Divine Providence had indeed overshadowed us and directed our movements. Had we gone on to the Koko-nor and attempted to return later, we should have found our way intercepted by the Mohammedan stronghold which a few days afterwards commanded the roads from Tankar to Kumbum.

CHAPTER III

A MOHAMMEDAN REBELLION

Moslem Sects – Beginnings of the Struggle – Our Acquaintance with the Abbot – Refuge in the Lamasery – The Doctrine of Reincarnation.

Among China's four hundred millions the Mohammedan element, though comparatively small, must be counted as a significant factor. Like a fomenting leaven, a hotbed of domestic turmoil within themselves, and ever and anon working to the surface of the national life, the followers of the Prophet have proved a constant source of trouble to the Chinese authorities, especially in the provinces of Shensi, Yunnan and Kansu, where they have planted their most extensive colonies. According to Dr. Martin, there are about ten millions of them throughout the empire, although other authorities place the number much higher. They are known by the general appellation of Siao-chiao, that is, adherents of the "small religion," as opposed to the Chinese, who, with their complex cult of ancestor worship, idolatry and incense burning, are of the Ta-chiao, or "great religion," the comparative magnitude of the two religions being estimated of course by the relative number of their adherents. The Mohammedans are further distinguished from the Chinese by their abstaining from opium, wine, tobacco, pork and other meats except when killed by a Mohammedan slaughterer who has been specially authorized by the ahon. Travelers, for this reason, may always be certain of getting good, clean meat from Mohammedan butchers, whereas the Chinese do not scruple to cut up and offer for sale an animal that has died of disease. Besides being generally clean, the Mohammedans are industrious, making a success of whatever calling they embrace, be it that of a merchant, muleteer, carter, cook, innkeeper, or worker in copper, silver or iron. Their restaurants along the great highways enjoy the liberal patronage of all classes, while on the other hand no Mohammedan will partake of the "ceremonially unclean" dishes of the ordinary innkeeper of the Ta-chiao persuasion.

The Mohammedans of the province of Kansu, numbering about one million and a half, constitute one-fourth of its population. In the principal cities, such as Lancheo, the capital, and Sining, they monopolize the suburbs, and whole villages and towns of them are to be found in various parts of the province, even as far west as the Tibetan border. Besides being known under the usual designation of Siao-chiao, to distinguish them religiously from the Chinese, they are also called by the latter Huei-huei, while the Tibetans and Mongolians speak of them as K'a-che. Though now having lost to a considerable extent their racial characteristics through intermarriage with the Chinese, they are still recognized as the descendants of the great migrations which came from Turkestan, Kashmir, and Samarkand nearly five centuries ago. They are divided into two sects, called the "white-capped" and "black-capped," the latter being identical with the Salars, who are much more fanatical and exclusive than the other sect. In the Sining district the two divisions are known as the Lao-chiao, or "old religion," and the Sin-chiao, or "new religion," the latter being, as far as we could ascertain, the same sect as the Salars, or "black-capped" Mohammedans. They have not merged nearly so agreeably with the Chinese as the former, for, while they are usually ready to rebel, the Lao-chiao, as a rule, remain neutral, or even cooperate with the Chinese.

The Salars who boast of their Samarkandi origin are settled around Hocheo, Hsuen-hua-ting, Mincheo and Taocheo, the first mentioned town of thirty thousand inhabitants being their stronghold, where the Chinese have to keep a large body of soldiers, as nearly every year for the most trivial reasons there is trouble. The Salars speak their own language, which is understood by travelers from Kashgar, and when we visited their country in 1897, Rahim, our Tibetan boy, a native of Ladak, was delighted that he could converse in their own tongue, which he had learned on his journeys into Turkestan. The men have a purely foreign look, good figures, oval faces, aquiline noses, and wear the Chinese queue, while the women do not bind their feet, though the Mohammedans around us were as much in love with small feet as were the pure Chinese. They are all supposed to be conversant with Arabic, but, as a fact, have not usually much knowledge of it, except the ahons, some of the latter being Turkestani. Occasionally some great mufti from Mecca or other important Moslem center visits the faithful in Kansu, exhorting them to greater zeal; while the many mosques that tower above the Chinese dwellings, the dogged fidelity with which the devotees perform their religious services, and the death-embracing fanaticism with which in times past they have fought for their faith, all attest the vigorous hold which Mohammedanism has gained in the land of Confucius.

The religious dissimilarities between the two sects are trivial, the lines of cleavage being quite as insignificant as some that divide Christendom. The chief bone of contention is a difference of opinion as to the hour at which the fast may be broken during the Ramadan, and as to the propriety of incense burning. The cause of the dispute which culminated in one of the most sanguinary and disastrous wars that ever took place in Western China was the question as to whether or not a Mohammedan might wear a beard before the age of forty!

It need not be wondered at that terror filled the minds of the people of Lusar and Kumbum, and of all the surrounding villages, when the news spread that the Mohammedan sword was again unsheathed; for fresh in their memories were the terrible atrocities perpetrated during the former uprising, which was one long intermittent period of bloodshed and pillage lasting from 1861 to 1874, both parties, however, assenting to a cessation of hostilities each year during seedtime and harvest. The government troops sent to subdue the rebels had been, on account of their inadequate numbers, hewn down, harrassed and beaten year after year, and only succeeded finally in quelling the outbreak because of a dissension among the Mohammedans themselves as to whether the Koran sanctioned the use of tobacco. Our own little Lusar had in those troublous times been twice destroyed, while before the rebellion Kumbum, the great monastery, had been the residence of 7,000 lamas, hundreds of whom dyed their temple thresholds with their blood, falling in defense of their treasures and their homes, repulsing the rebels barely in time to save their treasure-house, and to keep unholy hands from ravishing their gold-tiled temples. Whenever the lamas look at the bullet-pierced silver bowl which is still in service on one of the altars, they remember that Kumbum's palmiest days ended in that great struggle, for never since has it contained more than four thousand lamas.