Memoirs

of an

Arabian Princess

CHAPTER I

FAMILY HISTORY

THE PALACE OF BET IL MTONI — THE BATHHOUSES — EQUESTRIAN AND OTHER AMUSEMENTS — PRINCESS SALAMAH'S FATHER — PURCHASE OF HER MOTHER — SEYYID SAÏD'S PRINCIPAL AND SECONDARY WIVES — HIS CHILDREN — THE BENJILE — A QUESTION OF DISCIPLINE — BROTHER MAJID REACHES HIS MAJORITY — THE AUTHORESS'S FIRST CHANGE OF RESIDENCE

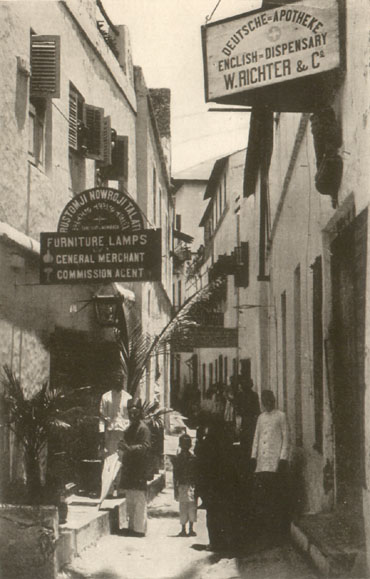

IT WAS at Bet il Mtoni, our oldest palace in the island of Zanzibar, that I first saw the light of day, and I remained there until I reached my seventh year. Bet il Mtoni is charmingly situated on the seashore, at a distance of about five miles from the town of Zanzibar, in a grove of magnificent cocoanut palms, mango trees, and other tropical giants. My birthplace takes its name from the little stream Mtoni, which, running down a short way from the interior, forks out into several branches as it flows through the palace grounds, in whose immediate rear it empties into the beautiful sparkling sheet of water dividing Zanzibar from the continent of Africa.

A single, spacious courtyard is allotted to the whole body of buildings that compose the palace, and in consequence of the variety of these structures, probably put up by degrees as necessity demanded, the general effect was repellent rather than attractive. Most perplexing to the uninitiated were the innumerable passages and corridors. Countless, too, were the apartments of the palace; their exact disposition has escaped my memory, though I have a very distinct recollection of the bathing arrangements at Bet il Mtoni. A dozen basins lay all in a row at the extreme end of the courtyard, so that when it rained you could visit this favourite place of recuperation only with the help of an umbrella. The so-called "Persian" bath stood apart from the rest; it was really a Turkish bath, and there was no other in Zanzibar. Each bath-house contained two basins of about four yards by three, the water reaching to the breast of a grownup person. This resort was highly popular with the residents of the palace, most of whom were in the habit of spending several hours a day there, saying their prayers, doing their work, reading, sleeping, or even eating and drinking. From four o'clock in the morning until twelve at night there was constant movement; the stream of people coming and leaving never ceased.

Entering one of the bath-houses — they were all built on the same plan — you beheld two raised platforms, one at the right and one at the left, laid with finely woven matting, for praying or simply resting on. Anything in the way of luxury, such as a carpet, was forbidden here. Whenever the Mahometan says his prayers he is supposed to put on a special garment, perfectly clean — white if possible — and used for no other purpose. Of course this rather exacting rule is obeyed only by the extremely pious. Narrow colonnades ran between the platforms and the basins, which were uncovered except for the blue vault of heaven. Arched stone bridges and steps led to other, entirely separate apartments. Each bath-house had its own public; for, be it known, a severe system of caste ruled at Bet il Mtoni, rigidly observed by high and low.

Orange trees, as tall as the biggest cherry trees here in Germany, bloomed in profusion all along the front of the bath-houses, and in their hospitable branches we frightened children found refuge many a time from our horribly strict school-mistress! Human beings and animals occupied the vast courtyard together quite amicably, without disturbing each other in the very least; gazelles, peacocks, flamingoes, guinea fowl, ducks, and geese strayed about at their pleasure, and were fed and petted by old and young. A great delight for us little ones was to gather up the eggs lying on the ground, especially the enormous ostrich eggs, and to convey them to the head-cook, who would reward us for our pains with choice sweetmeats.

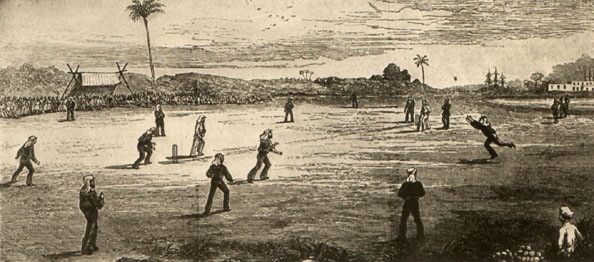

Twice a day, early in the morning and again in the evening, we children — those of us who were over five years old — were given riding lessons by a eunuch in this courtyard, without at all disturbing the tranquillity of our animal friends. As soon as we had attained sufficient skill in the equestrian art, our father presented us with beasts of our own. A boy would be allowed to pick out a horse from the Sultan's stables, while the girls received handsome, white Muscat mules, richly caparisoned. Riding is a favourite amusement in a country where theatres and concerts are unknown, and frequently races were held out in the open, which but too often would end with an accident. On one occasion a race nearly cost me my life. In my great eagerness not to be outstripped by my brother Hamdan, I galloped madly onward without observing a huge bent palm tree before me; I did not become aware of the obstacle until I was just about to run my head against it, and, threw myself back, greatly terrified, in time to escape a catastrophe.

A peculiar feature of Bet il Mtoni were the multitudinous stairways, quite precipitous and with steps apparently calculated for Goliath. And even at that you went straight on, up and up, with never a landing and never a turn, so that there was scarcely any hope of reaching the top unless you hoisted yourself there by the primitive balustrade. The stairways were used so much that the balustrades had to be constantly repaired, and I remember how frightened everybody was in our wing, one morning, to find how both rails had broken down during the night, and to this very day I am surprised that no accident occurred on those dreadful inclines, with so many people going up and down, the round of the clock.

|

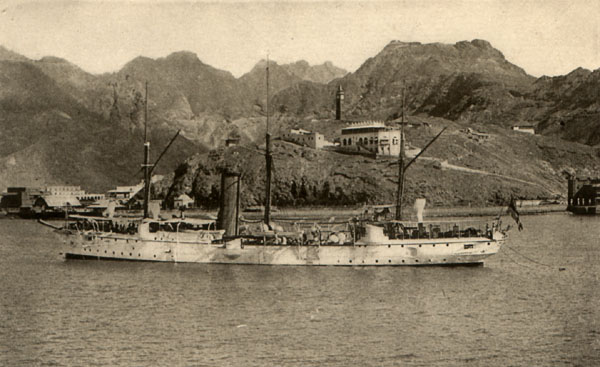

| Photograph by Coutinho Brothers, Zanzibar |

| THE SULTAN'S PALACE TO-DAY |

Statistics being a science unfamiliar to the inhabitants of Zanzibar, no one knew exactly how many persons lived at the palace of Bet il Mtoni, but were I to hazard an estimate, I think I should not be exaggerating if I put the total population at a thousand. Nor will this large number seem excessive if one considers that whoever wants to be regarded as wealthy and important in the East must have an army of servants. No less populous, in fact, was my father's town palace, called Bet il Sahel, or Shore House. His habit was to spend three days a week there, and the other four at Bet il Mtoni, where resided his principal wife, once a distant relative.

My father, Seyyid Saïd, bore the double appellation of Sultan of Zanzibar and Imam of Muscat, that of Imam being a religious title and one originally borne by my great-grandfather Ahmed, a hereditary title, moreover, which every member of our family has a right to append to his signature.

As one of Seyyid Saïd's youngest children, I never knew him without his venerable white beard. Taller in stature than the average, his face expressed remarkable kindness and amiability though at the same time his appearance could not but command immediate respect. Despite his pleasure in war and conquest, he was a model for us all, whether as parent or ruler. His highest ideal was justice, and in a case of delinquency he would make no distinction between one of his own sons and an ordinary slave. Above all, he was humility itself before God the Almighty; unlike so many of great estate, arrogant pride was foreign to his nature, and more than once, when a common slave of long and faithful service took a wife, my father would have a horse saddled, and ride off alone to offer the newly wedded couple his good wishes in person.

My mother was a Circassian by birth. She, together with a brother and a sister, led a peaceful existence on my father's farm. Of a sudden, war broke out, the country was overrun by lawless hordes, and our little family took refuge "in a place that was under the ground" — as my mother put it, probably meaning a cellar, a thing unknown in Zanzibar. But the desperate ruffians found them out; they murdered both of my mother's parents, and carried away the three children on horseback. No tidings ever reached my mother as to the fate of either brother, or sister. She must have come into my father's possession at a tender age, as she lost her first tooth at his home, and was brought up with two of my sisters of her own years as companions. Like them she learned to read, an accomplishment which distinguished her above the other women in her position, who usually came when they were at least sixteen or eighteen, and by that time of course had no ambition to sit with little tots on a hard schoolroom mat. She was not good-looking, but was tall and well-built, and had black eyes; her hair also was black, and it reached down to her knees. Of a sweet, gentle disposition, nothing appealed to her more than to help someone who might be in trouble. She was always ready to visit, and even to nurse invalids; to this very day I remember how she would go from one sick bed to another, book in hand, to read out pious counsels of comfort.

My mother had considerable influence with Seyyid Saïd, who rarely denied her wishes, though they were for the most part put forward on behalf of others. Then, too, when she came to see him, he would rise, and step toward her — a signal distinction. Mild and quiet by nature, she was conspicuously modest, and was honest and open in all things. Her intellectual attainments were of no great account; on the other hand, she showed admirable skill at needlework. To me she was a tender, loving mother, which, however, did not prevent her from punishing me severely when I deserved it. Her friends at Bet il Mtoni were numerous, a rare circumstance for a woman belonging to an Arab household. No one's faith in God could have been stronger. I call to mind a fire, which broke out one moonlight night in the stables, while my father was in town with his retinue. Upon a false alarm that our house had caught, my mother seized me under one arm and her large Koran under the other, and ran out of doors. Nothing else concerned her, in that moment of peril.

So far as I can remember, my father — the Seyyid, or Sultan — had only one principal wife, from the time I was born; the other, secondary wives, numbering seventy-five at his death, he had bought from time to time. His principal wife, Azze bint Sef, of the royal house of Oman, held absolute sway in his home. Although small and insignificant-looking, she exercised a singular power over her husband, who fell in readily with all of her ideas. Toward the Sultan's other wives and to his children she behaved with domineering haughtiness and censoriousness; luckily she had no children of her own, else their tyranny would certainly have been unendurable. Every one of my father's children — there were thirty-six when he died — was by a secondary wife, so that we were all equals, and no questions as to the colour of our blood needed to be raised.

This principal wife, who had to be addressed as "Highness" (for which the Arabic is Seyyid and the Suahili Bibi), was hated and feared by young and old, high and low, and liked by none. To this day do I remember how stiffly she would pass everybody by, hardly ever dropping a smile or a word. How different was our kind old father! He always had a pleasant greeting to give, whether the person was one of consequence or a lowly subordinate. But my high and mighty stepmother knew how to keep herself on the top of her exalted rank, and no one ever ventured into her presence without being specially invited. I never observed her to go out unless grandly escorted, excepting when we went with the Sultan to their bath-house, intended for their exclusive use. Indoors, whoever met her was completely awestruck, as is a private soldier here in the presence of a general. Thus the importance she gave herself was felt plainly enough, although upon the whole it did not seriously spoil the charm of life at Bet il Mtoni. Custom demanded that all of my brothers and sisters should go and wish her a "good morning" every day; but we detested her so cordially that scarcely one of us ever went before breakfast, which was served in her apartments, and in this way she lost a lot of the deference she was so fond of exacting.

Of my senior brothers and sisters some were old enough to have been my grandparents, and one of my sisters had a son with a grey beard. In our home no preference was shown to the sons above the daughters, as seems to be imagined in Germany. I do not know of a single case in which a father or mother cared more for a son than for a daughter simply because he was a son. All that is quite a mistake. If the law allows the male offspring certain privileges and advantages — for example, in the matter of inheritance — no distinction is made in the home treatment given to children. It is natural enough, and human too, that sometimes one child should be preferred to another, whether here in this country or in that far southern land, even though the fact may not be openly acknowledged. So with my father; only it happened that his favourite children were not boys, but two of my sisters, Sharife and Chole. One day my lively young brother Hamdan — we were both about nine years old at the time — accidentally shot an arrow into my side, without, however, doing me much injury. The affair coming to my father's ears, he said to me: "Salamah, send Hamdan here"; and he scolded the offender in such terms as to make his ears tingle for many a day after.

The pleasantest spot at Bet il Mtoni was the benjile — close to the sea, in front of the main building — a huge, circular, open structure where a ball could have been given, had such a custom been in vogue with our people. This benjile somewhat resembled a merry-go-round, since the roof, too, was circular; the tent-shaped roof, the flooring, the balustrades, all were of painted wood. Here my dear father was wont to pace up and down by the hour with bent brow, sunk in deep reflection. He limped slightly; during a battle a ball had struck his thigh, where it was now permanently lodged, hindering his gait, and occasionally giving him pains. A great many cane chairs — several dozen, I am sure — stood about the benjile, but besides these, and an enormous telescope for general use, it contained nothing else. The view from our circular look-out was splendid. The Sultan was in the habit of taking coffee here two or three times a day with Azze bint Sef and all of his adult offspring. Whoever wanted to speak to my father in private would be apt to find him alone in this place at certain hours. Opposite the benjile the warship Il Ramahni lay at anchor the year round, her purpose being to wake us up early by a discharge of cannon during the month of fasting, and to man the rowboats we so often employed. A tall mast was planted before the benjile, intended for the hoisting of the signal flags which ordered the desired boats and sailors ashore.

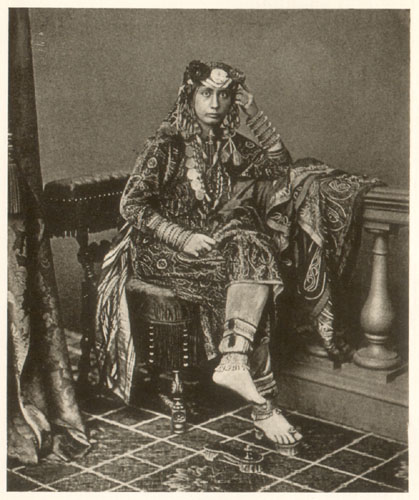

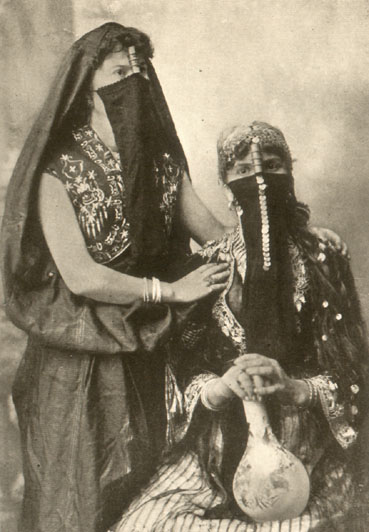

As for our culinary department, Arabian cooking, and Persian and Turkish as well, prevailed both at Bet il Mtoni and Bet il Sahel. For both establishments harboured persons of various races, with bewitching loveliness and the other extreme fully represented. But only Arabian dress was allowed to us, while the blacks wore the Suahili costume. If a Circassian arrived in her flapping garments or an Abyssinian in her fantastic draperies, either was obliged to change within three days, and to wear the Arabian clothes provided her. As in this country every woman of good standing considers a hat and a pair of gloves indispensable articles, in the East ornaments are essential. In fact ornaments are so imperative that one even sees beggar-women wearing them while plying their trade.

At his Zanzibar residences and at his palace of Muscat, in Oman, my father kept treasuries full of Spanish gold coins, English guineas, and French louis; but they contained as well all sorts of jewellery and kindred female adornments, from the simplest trifles to coronets set in diamonds, all acquired with the object of being given away. Whenever the family was increased, through the purchase of another secondary wife or the birth — a very frequent event — of a new prince or princess, the door of the treasury was opened, so that the newcomer might be suitably endowed according to his, or her rank and position. In case of a child being born, the Sultan would usually visit mother and child on the seventh day, when he would bring ornaments for the infant. A newly arrived secondary wife would likewise be presented with the proper jewellery soon after she was bought, and at the same time the head eunuch would appoint the domestics for her special service.

Although my father observed the greatest simplicity for himself, he was exacting toward the members of his household. None of us, from the oldest child to the youngest eunuch, might ever appear before him except in full dress. We small girls used to wear our hair braided in a lot of slender little plaits, as many as twenty of them, sometimes; the ends were tied together; and from the middle a massive gold ornament, often embellished with precious stones, hung down the back. Or a minute gold medal, with a pious inscription, was appended to each little plait, a much more becoming way of dressing the hair. At bed-time nothing was taken off us but these ornaments, which were restored next morning. Until we were old enough to go about veiled, we girls wore fringes, the same that are fashionable in Germany now. One morning I surreptitiously escaped without having my fringe dressed, and went to my father for the French bonbons he used to distribute among his children every morning, but instead of receiving the anticipated sweetmeats, I was packed out of the room because of my unfinished toilette, and marched off by an attendant to the place from which I had decamped. Thenceforth I took good care never to present myself incompletely beautified before the paternal eye!

Among my mother's intimates were two of the secondary wives who were Circassian, like herself, and who came from the same district as she did. Now, one of my Circassian stepmothers had two children, Chaduji and her younger brother Majid, and their mother had made an agreement with mine that whichever parent survived, should care for the children of both. However, when Chaduji and Majid lost their mother they were big enough to do without the help of mine. It was usual in our family for the boys to remain under maternal tutelage until they were about eighteen to twenty, and when a prince reached this age he was declared to have come to his majority, that is to say, the formalities took place sooner or later, according to his good or bad conduct. He was then considered an adult, a distinction as eagerly coveted in that country as anywhere else; and he was at the same time made the recipient of a house, servants, horses, and so on, beside a liberal monthly allowance.

So my brother Majid attained his majority, which he had merited rather by his disposition than his years. He was modesty itself, and won all hearts through his charming, lovable ways. Not a week passed but he rode out to Bet il Mtoni (for, like his deceased mother, he lived at Bet il Sahel), and although my senior by a dozen years played games with me as if we had both been of the same age.

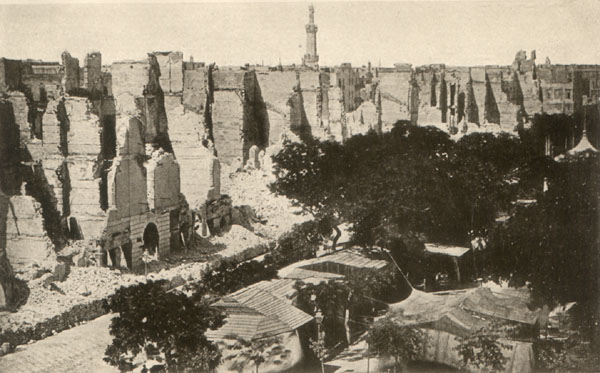

|

| Photograph by A. C. Gomes & Co., Zanzibar |

| RUINS OF PRINCESS SALAMAH'S EARLY HOME. |

One day, then, he arrived with the glad news that his majority had been announced by his father, who had granted him an independent position and a house of his own. And he besought my mother most urgently to come and live, with me, in his new quarters, Chaduji sending the same message. To his impetuous pleading my mother objected that without his father's consent she could not accept, and said she must therefore first consult him; as for her, she was willing enough to share Majid's and Chaduji's dwelling if they wished. But Majid offered to save my mother this trouble by himself asking the Sultan's sanction, and the next day, in fact — my father happening to be at Bet il Sahel — he brought back the coveted permission. Thus our transmigration was decided upon. After a long talk between my mother and Majid, it was concluded that we should not move for a few days, when he and Chaduji would have had time to make the necessary arrangements for accommodating us.

CHAPTER II

BET IL WATORO

MAHOMETAN BELIEF IN FOREORDINATION — PARTING GIFTS — A LITTLE JOURNEY BY STATE CUTTER — BET IL WATORO — ARABIAN HOUSE FURNITURE AND DECORATION — HOMESICKNESS — MAJID'S FIGHTING-COCKS — AMAZONIAN ACCOMPLISHMENTS — ORAL MESSAGES AND WRITTEN — CHADUJI THE HAUGHTY

THE change, after all, was not an easy one for my mother. She felt deeply attached to Bet Il Mtoni, since she had spent most of her life there; besides, she disliked novelty. Yet the idea of possibly being of some help to her friend's children outweighed her personal inclinations, as she afterward told me. Scarcely had her decision to move become known, when on all hands the complaint was addressed to her: "Jilfidan (this was my dear mother's name), is your heart closed to us, that you are deserting us forever?" "Ah, my friends," was her reply, "it is not by my will that I leave you; but my departure is ordained." No doubt some readers will mentally cast a glance of pity at me, or shrug their shoulders, because I say "ordained." Perhaps those individuals have hitherto kept their ears and eyes shut against the will of God, rejecting His divine manifestations while allowing mere chance full sway. It must, of course, be noted that the author of this book was originally a Mohometan, and that she was brought up as such. Furthermore, I am telling about Arabian life, about an Arabian household, where — in a real Arabian family — two things were totally unknown, that word "chance" and also materialism. The Mahometan acknowledges God not only as his creator and preserver; but is conscious of the Lord's omnipresence, and believes that not his own will, but the Lord's must govern in all matters, great or small.

Several days sped by pending our preparations, and we then waited for the return of Majid, who was to supervise our journey in person. Three playmates I particularly regretted leaving, two of my sisters and one of my brothers, almost exactly my age. On the other hand, I was overjoyed at the prospect of bidding adieu to our new, unmercifully severe schoolmistress. Owing to the forthcoming separation, our quarters resembled a huge beehive. Everybody, according to their circumstances and degree of affection, brought us farewell presents — a very popular custom there. However trifling the present he is able to give, nothing will induce an Arab to withhold it from the departing friend. I remember a case in point. One day — I was quite a small girl then — after visiting a plantation, we were about to start the homeward journey to Bet il Mtoni in our boats. Suddenly, I felt a slight jerk at my sleeve, and upon turning round beheld a little old Negro woman. She handed me an article wrapped in banana leaves, saying, "This is for you, mistress, in honour of your departure; it is the first ripe thing from my plot." Speedily opening the leaves, I found a freshly picked head of maize. I did not know the old Negro woman, but subsequently learned that she was a long-standing favourite of my mother's.

Well, at last Majid arrived, with the announcement that the captain of the Ramahni had been ordered to send a cutter for us the next evening and another boat for the luggage and the escort. My father happened to be at Bet il Mtoni the day we were to leave, and we repaired to the benjile expecting to find him there. He was thoughtfully pacing up and down, when, seeing my mother approach, he came forward to meet her. They were soon absorbed in a lively conversation touching the journey, the Sultan having meanwhile commanded a eunuch to bring me some sweetmeats and sherbet, probably to stop my everlasting questions. As may easily be imagined, I was tremendously excited and curious regarding our future home, and in fact about everything that concerned the town-life. Up till then, I had been in town only once, and but for a very short time, hence I had the acquaintance of many brothers, sisters, and stepmothers in store for me. We eventually betook ourselves to the apartments of the high and mighty Azze bint Sef, who graciously vouchsafed to dispose of us standing up, a concession on her part, so to speak, because she usually received and dismissed people in a sitting position. My mother and I were privileged to touch her dainty hand with our lips — and to turn our backs upon the lady forever. Then we travelled upstairs and down, to say good-bye to our friends, but barely half were in, so my mother determined to go back at the next hour for prayer, when she would be sure to see them all.

At seven in the evening our large cutter — not used except on special occasions — appeared before the benjile. She was manned by a dozen sailors, I remember, and at the stern, as well as at the bow hung a plain crimson flag, our ensign, which bears no pattern nor any kind of symbol. The rear part of the vessel was covered with an expansive awning, and under this were silken cushions for perhaps ten persons. Old Jahar, a trusted eunuch of my father, came to inform us that everything was in readiness; he and another eunuch had been ordered to accompany us by the Sultan, who watched us from the benjile. Our friends saw us to the door with weeping eyes, and their sorrowful "Wedah! Wedah!" (Good-bye! Good-bye!) rings in my ears to this very day.

Our beach was rather shallow, and we had no landing stage of any sort. There were three methods, however, of reaching your boat. You sat on a chair, which was transported by lusty sailor-men; or you mounted on one of their backs; or you simply walked across by a plank from the dry sand to the edge of the craft, and this was the method chosen by my mother, only she was supported on either side by a wading eunuch. Another eunuch carried me over, and put me down in the stern with my mother and old Johar. The cutter was lit with coloured lamps, and as soon as we started the rowers intoned a slow rhythmic chant, according to Arabian custom. We skirted the coast-line, as usual, while I went fast asleep. I was awakened by the sound of many voices calling out my name. Decidedly startled, though half drowsy, I observed that we were arriving at our destination. The boat stopped almost under the windows of Bet il Sahel; they were brilliantly illuminated, and full of spectors, mostly my strange brothers and sisters and stepmothers. Some of the children were younger than myself, and no less anxious to make my acquaintance than I theirs; it was they who clamoured for me so loudly when the expected cutter appeared. The landing was accomplished in the same manner as the embarkation. My young brothers greeted me with more than enthusiasm, insisting, too, that we must accompany them at once; but my mother of course declined, since otherwise Chaduji, who was then already waiting at the window of her own house, would have been disappointed by the delay. To be sure I was grieved enough at not being allowed to go with my brothers and sisters immediately, having long looked forward to that happy moment, yet I knew my mother well enough to be aware that she would not change her mind once it was made up; despite her incomparably unselfish love toward me, she was always quite firm and resolute. Meanwhile she comforted me by promising to take me to Bet il Sahel for a whole day upon my father's return thither.

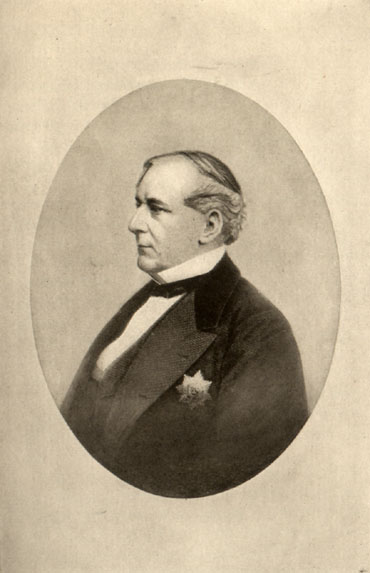

|

| Photograph by A. C. Gomes & Co., Zanzibar |

| SEA FRONT OF THE CITY OF ZANZIBAR. |

So we passed on to Bet il Watoro, Majid's house, which lay quite close to Bet il Sahel, and likewise commanded a fine view of the sea. We found my sister Chaduji awaiting us at the foot of the stairs. She welcomed us right heartily to Bet il Watoro, and led us to her apartments, where a servant soon brought us all kinds of refreshments. Majid and his friends remained in the anteroom, not being allowed to come up until Chaduji sent permission by my mother's request. And how delighted that splendid, noble Majid was at being able to welcome us to his home!

Our own room was of fair size, and from it was visible a neighbouring mosque. It was furnished like most Arabian rooms, and we found nothing lacking. One room was sufficient for us; wearing the same sort of clothes by night as by day, people of rank, with their fastidious cleanliness, can easily dispense with special rooms set apart for sleeping. Persons of wealth and distinction arrange their dwellings about as follows:

Persian carpets or daintily woven, soft mats cover the floor. The thick whitewashed walls are divided into compartments running perpendicularly from floor to ceiling, and these niches contain tiers of wooden shelves painted green, forming a succession of brackets. On the brackets stand arrayed the most exquisite and costly articles of glass and china, in symmetrical order. An Arab does not care what he spends in adorning his niches; let a handsomely painted plate or a tasteful vase or a delicately cut glass cost what it may, if it looks well he buys it. An effort is made to hide the bare spaces of wall between the compartments. Tall mirrors are put there, reaching from the low divan to the ceiling; they are usually ordered from Europe, with the dimensions exactly specified. Mahometans disapprove of pictures as trying to imitate the Divine creation, but latterly this objection has been losing force to some extent. Clocks, on the other hand, are in great vogue, and in a single house one often sees a whole collection; some are placed at the top of the mirrors and some in pairs on either side.

In the gentlemen's rooms the walls are decorated with trophies of valuable weapons from Arabia, Persia, and Turkey, with which every Arab embellishes his abode in the measure of his rank and riches. A large double bed of rosewood, adorned with marvellous carvings of East Indian workmanship, stands in the corner, shrouded entirely with white tulle or muslin. Arabian beds have very long legs; to get in the more comfortably you mount on a chair first, or borrow the hand of a chambermaid for a step. The space under the bed is often utilised for sleeping purposes too, for instance by nurses of children or invalids. Tables are quite rare, and only found in the possession of the highest personages, though chairs are common, both in kind and quantity. Wardrobes, cupboards, and the like are unfamiliar furniture, but you find a sort of chest with two or three drawers and a secret place besides for money and jewellery. These coffers — several of them to each room — are large and massive, and studded with hundreds of small brass-headed nails by way of ornaments. Windows and doors we would leave open all day, never shutting the windows at all except for a little while when it rained. Hence the phrase "I feel a draught" is unknown in that country.

At first my new quarters did not suit me in the least; I missed my young brothers and sisters too much, and Bet il Watoro seemed so cramped and confining when I thought of the immense Bet il Mtoni. "Am I to live here forever?" I continually kept asking myself the first few days; "and am I to sail my boats in a washtub?" for there was no river Mtoni here, so that the water had to be fetched from a well outside the house. When my good, kind mother, who would have liked to give away everything she owned, advised me to present my nice sail-boats, that I was so fond of, to my brothers and sisters at Bet il Mtoni, I would not hear of it. In short, I experienced feelings I had never undergone before, of great unhappiness, and I was deeply afflicted. But my mother was in her element. With Chaduji, she was occupied all day in planning and settling house-hold affairs, so that I saw very little of her. Majid gave me the most attention; the day after my arrival he took me by the hand, and showed me his whole domicile, from top to bottom. Only I could see nothing to admire; in fact I begged my mother fervently to go back with me as soon as possible to Bet il Mtoni and my accustomed playmates. This was of course out of the question, especially as she was genuinely useful in her new sphere.

I was glad to find a lover of animals in Majid, who kept a great variety of them. His white rabbits caused my mother and Chaduji fearful annoyance, since they ruined the new house. He also had a number of fighting cocks, from every corner of the earth; such a rich collection I have never even seen in a zoölogical garden. So I got into the habit of accompanying Majid whenever he visited his pets, and he most good-naturedly allowed me to share in his amusements. No very long period elapsed before I became the possessor — through his kindness — of a veritable army of fighting cocks which rendered my solitary existence at Bet il Watoro a great deal easier to bear. Nearly every day we marshalled our champions, conducted before us and taken away again by slaves. A cock-fight is by no means a dull business; the spectator's attention is fully engrossed, and the whole thing offers an entertaining, sometimes a comical, performance.

Later on Majid taught me how to fence with sword, dagger, and lance, and when we went into the country together we would practise pistol and rifle shooting. Thus I developed into something like an Amazon, to the utter dismay of my mother, who entirely disapproved of fencing and shooting. But I very much preferred manipulating these weapons to sitting still by the hour over needle or bobbin. Indeed, my new pursuits coupled with complete freedom — another mistress had not been found for me yet — soon cheered my spirits, so that my former aversion to the solitary Bet il Watoro began to fade. Nor did I neglect horsemanship; Mesrur, a eunuch, was ordered by Majid to continue the instruction he had begun. As I have said, my mother had little time to devote to me privately, being so monopolised by Chaduji. The result was that I attached myself by degrees to a trustworthy Abyssinian; her name was Nuren, and I learned some Abyssinian from her, though I have forgotten it all long ago.

We remained in constant communication with Bet il Mtoni, where our friends received us with the warmest hospitality. Otherwise we kept in contact through verbal messages delivered by slaves. People do not care to correspond in the East, even if they know how to write. Everyone there of wealth and station owns several slaves, good runners particularly reserved for the transmission of messages. A runner must be able to cover a lot of ground in a day, but he is unusually well-treated and cared for; on his discretion and integrity — since he is intrusted with the most confidential matters — the welfare, or more, of his owners may depend. Occasionally a messenger of this kind for the sake of revenge destroys life-long relations of friendship. However, that induces few individuals to learn writing, and thus make themselves independent of their slaves for life; nowhere is the term "easy-going" fraught with deeper significance than in our country.

My sister Chaduji was extremely fond of company; hence Bet il Watoro often resembled nothing so much as a dove-cote. Hardly a day in the week but the house would be full of visitors from six in the morning till twelve at night. The guests arriving at six of the forenoon and intending to stay all day were met by the servants, and shown to a special apartment, waiting there until eight or nine before they were received by the mistress of the house. The interval between their arrival and formal reception, those lady visitors would spend in making up the lost hours of sleep in the aforesaid room.

|

| Photograph by Coutinho Brothers, Zanzibar |

| PANORAMA OF THE CITY OF ZANZIBAR. |

Though a close affection existed between myself and Majid, I was unable to conceive the same sort of liking for Chaduji. Imperious and fault-finding, her character differed in great degree from her brother's; and in this view of their unlikeness I was not alone, as everyone acquainted with both was well aware which was the more affable of the two. She was wont to be very cool, and even offensive, toward strangers, thereby gaining enemies rather than friends. Anything new or foreign inspired her with strong repulsion; despite her renowned hospitality, she was much put out if a European lady sent in her name, although such a call would last only a half or three-quarters of an hour at the very most. I confess she was a good, intelligent housekeeper, scarcely knowing a moment's idleness, and if any spare time did fall to her she would go sewing and stitching away as busily at clothes for her slaves' younger children as at other times she would be working at my brother Majid's shirts. I remember that three of these children were delightful little boys, whose father performed the functions of an architect in our service. They were my junior by a few years, but as I lacked companions of my own age they became my regular playmates, until I finally grew acquainted with my other brothers and sisters at Bet il Sahel.

CHAPTER III

BET IL SAHEL

A CROSS-GRAINED DOORKEEPER — FASCINATIONS OF CHOLE — THE VERANDA AT BET IL SAHEL — LIFE IN THE COURTYARD — AN OUTDOOR BUTCHERY, KITCHEN, AND LARDER — LOVE OF ARABS FOR THEIR HORSES — SOCIAL DISTINCTIONS AT TABLE — WHY BET IL SAHEL WAS PREFERABLE TO BET IL MTONI — RACE HATRED BETWEEN CIRCASSIANS AND ABYSSINIANS — CURSHIT — ENFORCED TUITION

THE day I had so ardently longed for at last arrived — that day, the whole of which I was to spend at Bet il Sahel, whither my mother and Chaduji were to take me. It was on a Friday — the Mahometan Sunday — that we left our house quite early in the morning, probably at five or six o'clock. We had not far to go, however, as our destination was scarcely more than a hundred steps away.

The faithful, but unbearably cantankerous old doorkeeper gave us anything but an amiable welcome. He complained that he had been on his shaky old pins for the last hour answering female visitors. A Nubian slave belonging to my father, his beard had grown white in honourable service: I say "beard" advisedly, because male Arabs are in the habit of shaving their heads. My father was much attached to him, particularly since this servant had once saved him from committing a hasty act which he might have regretted all his life, by knocking a sword out of his hand just as he was about to strike down a man who had roused his anger. But we small children had no respect for the old fellow's virtues, and in the exuberance of a frolicsome mood would often play naughty tricks on this ancient and worthy servitor. We were particularly fond of abstracting his keys, and I suppose there was hardly a room in the whole of Bet il Sahel where they had not lain hidden from him at one time or another. One of my young brothers seemed to have a peculiar aptitude for secreting those keys in places unsuspected even by us conspirators.

Ascending from the ground floor to the first story, we found the ladies of the house all astir and active, only that the exceptionally pious were still engaged in their morning devotions, and hence invisible to the outer world. No one would think of disturbing a Mahometan at prayer under any circumstances, no, not even if the house should take fire. Our father was one of the devout worshippers on this occasion, and so we were obliged to wait until his prayers were done. Our visit had purposely been arranged to coincide with his presence at Bet il Sahel, to which, in fact, the unusual concourse was due. It must not be imagined that the ladies assembled were all friends or acquaintances of ours. On the contrary, some were entire strangers to us, and most of these came from Oman, our virtual mother-country, to ask my father for assistance of a material kind, which, indeed, was rarely denied. Our mother-country is as poor as our relatives there, and our own prosperity really dated from my father's conquest of the rich island of Zanzibar.

If the law prohibits, in general, a woman from holding personal intercourse of any sort with a strange man, it makes two exceptions, in favour of the sovereign and of the judge. Now, as thousands and thousands are totally ignorant of penmanship, and therefore cannot make their petitions in writing, nothing remains for such needy ones but to come themselves, even if they have to undertake the little journey from Asia to Africa. At all events, my father used to endow his petitioners according to their rank and position, omitting to harass the poor wretches with a lot of questions, as the custom is in Europe. It was assumed that nobody would go begging other people's help for pure amusement's sake, and I daresay this may frequently apply to Germany as well.

My brothers and sisters — whether previously acquainted with me or not — were all most cordial in their manner of welcome, none more so than the perfect Chole, dear to my memory forever. Hitherto the affections of my young heart had been entirely devoted to my sweet mother, but now I began to worship this angel of light as well. Chole soon became my ideal; she was greatly admired by others and was Seyyid Saïd's favourite daughter. Anyone judging her impartially and unenviously felt obliged to acknowledge her extraordinary beauty; and where is the human being completely insensible to the charm of beauty? Bet il Sahel contained no such misanthropist, at any rate. This sister of mine was without peer in our family, her good looks being positively proverbial. Though fine eyes are not at all uncommon in the East — as everyone must be aware — she was inevitably called Star of the Morning. An Arab chief from Oman once inflicted an injury upon himself through falling too deeply under the spell of her fascination. In the course of a sham fight, enacted before our house, the chief caught sight of her at a window, and became so enraptured with Chole's appearance that he forgot everybody and everything about him, and in this fit of amorous abstraction planted the point of his spear into his foot, not noticing the blood and feeling no pain, until awakened from his blissful dream by one of my brothers.

Bet il Sahel is relatively much smaller than Bet il Mtoni, and is likewise situated hard by the sea; there is something smiling and pleasant about the place which is reflected in the residents. All the living-rooms of Bet il Sahel command a glorious view of the water and the shipping. Well do I remember the enchanting scene. The doors of the living-rooms — which are all on the upper story — open on a long, broad veranda, the most magnificent I have ever seen. The veranda has a roof supported by pillars reaching to the ground, and has a balustrade along its entire length. Numerous chairs were set out, and coloured lamps hung up, which by night lent the house an aspect of fairyland. You looked down over the balustrade into the courtyard — the liveliest, noisiest spot imaginable — communication between which and the upper story being maintained by means of two large stairways. It was up and down, down and up, all day and all night, and often there was such a crowd at the foot or head of the stairs that it was difficult to reach them.

In a corner of the yard cattle were slaughtered, skinned, and cleaned in quantities, all for the sole use of the house, which, like every house in Zanzibar, must provide its own meat. In another corner sat Negroes having their heads shaved, while near them a lot of lazy water-carriers lay full length on the ground, paying not the slightest attention to the urgent calls for water, until unpleasantly reminded of their duty by a muscular eunuch. I have known these leisurely gentleman to start up, and to dash away like lightning with their jugs at the mere frown of their formidable taskmasters. Near by nurses sunned themselves and their little charges, whom they were regaling with fairy tales and stories. The kitchen, too, was in the open, and the smoke ascended freely to heaven as it might fancy, for chimneys do not exist. Strife and confusion were the rule among the host of culinary sprites, the head cooks dealing out boxes on the ears in liberal style to the quarrelsome or dilatory scullions of either sex. In the Bet il Sahel kitchen the animals were cooked whole, and I have seen a fish arrive carried by two sturdy blacks; small fish were not taken in excepting by the basketload, nor fowl but by the dozen. Flour, rice, and sugar were reckoned wholesale by bags, while the butter, imported from the north, especially from the island of Socotra, came in jars of a hundredweight each. Only spices were measured by the pound. Still more astonishing was the quantity of fruit consumed. Every day thirty or forty, or even fifty, men brought loads of fruit on their backs, apart from the consignments delivered by the little rowboats which supplied the plantations along the shore. I am probably making no extravagant estimate if I put Bet il Sahel's daily consumption of fruit as high as the capacity of a railway van; but some days, for instance, during the mango harvest, the demand would be still larger. The slaves intrusted with all this fruit were extremely careless; they would plump the heavy baskets from their heads violently to the ground, so that half the contents would be bruised or squashed.

|

| Photograph by A. C. Gomes & Co., Zanzibar |

| BRINGING FRUIT INTO TOWN. |

The place was protected against the sea by a long wall about twelve feet thick, and when the tide was low some of the horses were tethered in front of this wall so that they might roll in the sand and enjoy themselves. My father was immensely attached to his thoroughbred steeds from Oman; he saw them regularly, and if one fell sick he would go to the stable, and satisfy himself that it was properly attended to. The fondness of Arabs for their favourite horses I can prove by my brother Majid's example. He owned a very handsome brown mare, and was exceedingly anxious that she should have a colt. So, when the time came for the fulfilment of this hope, he gave orders that he should be notified of the birth at whatever hour it might occur. Thus, we were actually roused up out of bed one night, at about two o'clock, to be informed of the happy event. The groom who bore the welcome news received a fine present from his overjoyed master. But this is no exceptional case; in Arabia Proper the devotion to horses is said to be still more intense.

Between half past nine and ten my elder brothers left their apartments to take breakfast with my father, in which repast not a single secondary wife, however great a favourite with the Sultan, was allowed to share. Besides his children and grandchildren — those who had passed infancy, that is to say — the only persons admitted to his table were the principal wife Azze bint Sef and his sister Assha. Social distinctions in the East are never observed more rigorously than at meals; one is extremely cordial and affable toward one's guests, just as people of high station are here in Europe, or perhaps even more so, though at meals one excludes them from one's company. The custom is so ancient that no one takes offence. In Zanzibar the secondary wives had a system of sub-distinctions. The handsome and expensive Circassians, fully conscious of their superior merits and value, refused to sit at table with the brown Abyssinian women. Thus each race, in accordance with a tacit understanding, kept to itself when eating.

At Bet il Sahel I got the impression that the residents of the place were a much gayer set than at Bet il Mtoni. The reason was that at Bet il Mtoni, Azze bint Sef ruled supreme over husband, stepchildren, their mothers, in short over everybody, whereas at Bet il Sahel, where Azze rarely appeared, everyone, my father not excepted, felt free and untrammelled. And I think my father must actually have appreciated this liberty of action very keenly, as he had for years sent no one to Bet il Mtoni for permanent residence unless by such person's request, although that place always had rooms empty, and the other was crowded. The overpopulation I speak of at last gave rise to so much inconvenience that my father hit upon the idea of putting wooden pavilions on the broad veranda to serve as living rooms; eventually he had another house built — which went by the name of Bet il Ras (Cape House) — on the sea-coast a few miles north of Bet il Mtoni, and which was designed particularly for the younger Bet il Sahel generation.

A painter would have found rich material for his brush on the veranda at Bet il Sahel. To begin with, there were quite eight or nine different facial hues to be taken account of, and the many colours and shades of the garments worn would have offered the most vivid contrasts. No less lively was the bustle and stir. Children of all ages tore about, squabbled, and fought; shouting and clapping of hands — taking the place of the Western bell-ringing — for servants, resounded incessantly; the enormous, thick, wooden sandals of the women, sometimes inlaid with silver or gold, made a distressing clatter. We children enjoyed the confusion of tongues immensely. Arabic was supposed to be the only language spoken, and in the Sultan's presence the rule was invariably obeyed; but no sooner was his back turned than a sort of Babel would break loose, Persian, Turkish, Circassian, Suahili, Nubian, Abyssinian, to say nothing of dialects. However, no one took exception to mere tumult but now and then an invalid, and our dear father was quite used to it, and never objected in the least.

Here, then, on the veranda, my sisters were assembled the day of my visit. They were festally clad in celebration of our Sunday and of Seyyid Saïd's coming; the mothers walked up and down or stood in groups, talking and laughing and joking so vivaciously that one not knowing the country would never have taken them for the wives of the same man. From the stairs sounded the clinking of arms worn by my brothers, who had also come to see their father, in fact, to spend the whole day with him.

More luxury and extravagance prevailed than at Bet il Mtoni, and I found better looking women than there, where my mother was the only Circassian but one. Here, on the other hand, the majority of the Sultan's wives were Circassians, who undoubtedly are much finer in appearance than the Abyssinians, though among them, too, great beauties may be seen. Of course these natural advantages gave rise to envy and malice on the other side: a Circassian of noble bearing would be avoided, if not detested — having offended no one but the chocolate-coloured Abyssinians simply because she looked dignified. Under such circumstances it was natural enough if ridiculous race hatreds manifested themselves among the children. Her virtues notwithstanding, the Abyssinian is usually of a spiteful, revengeful disposition, and when she flies into a temper goes beyond the limits not only of moderation but of decency. We daughters of Circassian mothers were called "cats" by our sisters who had Abyssinian blood in their veins, because some of us had the misfortune to possess blue eyes. And then they spoke to us sarcastically as "your Highness," as further proof of their indignation at our having come into the world with white skin. Nor did they forgive my father for selecting as pets his two daughters Sharife and Chole from the loathsome tribe of cats.

Under the oppressive Azze bint Sef, life at Bet il Mtoni had always been more or less cloistral; at Bet il Watoro I felt still lonelier; consequently I relished the cheerfulness and the movement at Bet il Sahel all the more. Two little nieces of mine, daughters of my brother Khaled, were brought from their home every morning to Bet il Sahel — and taken back in the evening — so that they might do their lessons with their young uncles and aunts, and play with them afterward. Curshit, Khaled's mother, a Circassian by birth, was a very unusual woman. Of heroic bodily stature, she combined extraordinary will power with a highly developed intelligence, and I do not remember encountering her equal among the members of my sex. On one occasion that Khaled represented my father, during his absence, it was said she governed our country, with Khaled as her puppet. Certainly her counsel was invaluable to our family, and her decisions were momentous. Her two eyes were so sharp and observing that they saw as much as Argus's hundred eyes. In matters of importance she showed the wisdom of Solomon. But the small children found her repulsive, and gladly avoided her.

Evening came at last, and we began to think of returning to Bet il Watoro. Suddenly my father announced, to my mother's infinite dismay, that I must resume my lessons. Upon her plea that it had been impossible to find a suitable governess, he decreed that I was to be sent to Bet il Sahel each morning, and taken back in the evening, like my two nieces; thus I should be instructed together with my brothers and sisters there. To me this news was most unpleasant: I was far too wild to get any joy out of sitting still; besides, my last mistress had altogether spoilt my taste for lessons. Yet momentarily the prospect of being with my brothers and sisters all day — except on Fridays — comforted me, especially as my charming sister Chole offered to take charge of me and watch over me. And so she did — like a mother. My real mother grieved terribly over my father's order separating us six days in a week, but of course, she was obliged to acquiesce. She however bade me show myself several times during the day at a certain spot, by which means she could catch a glimpse of me from Bet il Watoro, and wave her greetings.

CHAPTER IV

FURTHER REMINISCENCES OF CHILDHOOD

JUVENILE TRICKS — PRINCESS SALAMAH CLIMBS A PALM TREE — MAJID'S SEIZURE — A FAMILY QUARREL WHICH ENDS IN DIVORCE AND ANOTHER CHANGE OF ABODE FOR THE AUTHORESS — EXTRAVAGANCE OF A PERSIAN SULTANA — MORE DIVORCE — LESSONS IN CALIGRAPHY

I LIKED Bet il Sahel more and more, for we had our own way there to a far greater extent than at Bet il Watoro. Nor did we miss many opportunities to play silly tricks, and when punishment was the result I fared better than the others, on account of Chole's extreme good nature.

We owned several handsome peacocks, one of which possessed an ugly disposition and could not endure us children. One day, as five of us were crossing over from Bet il Sahel to Bet il Tani — a sort of annex to the former — the peacock in question suddenly made a furious attack upon my brother Djemshid. We all immediately pounced upon the monster and vanquished it, but were much too angry to think of letting it go without a reminder for its misconduct. So we concluded upon a hideous revenge, and pulled out the bird's handsomest tail feathers. And what a pitiful wreck that proud, bellicose beauty looked then! Luckily our father happened to be in Bet il Mtoni that day, and the affair was hushed up by the time he returned.

I remember that two Circassians joined us, from Egypt, and that we children noticed how haughty one of them was, ignoring us completely, in fact. This struck at our vanity; we accordingly tried to hatch out some scheme for the offender's undoing. It was no easy matter to reach her, as she avoided us, and we never had any dealings with her. But this only aggravated us the more, especially as she was our senior by only a few years. One day, passing her room, we found the door open. She was sitting on a fragile Suahili bed, constructed of little else but a mat attached by cords to four posts. She was merrily singing some national ditty to herself. My sister Shewane acted as ringleader; she gave us a significant glance of which we, all kindred spirits, were not slow to catch the meaning. In a moment we had rushed in, seized the bed at its four corners, lifted it up as high as we were able, and let it bump down to the floor again, to the great terror of the amazed occupant. It was a childish trick, but was warranted by the effect it had, which was to cure our victim of her indifference toward us for good and all, so that ever after she was affability itself. Our object was therefore attained.

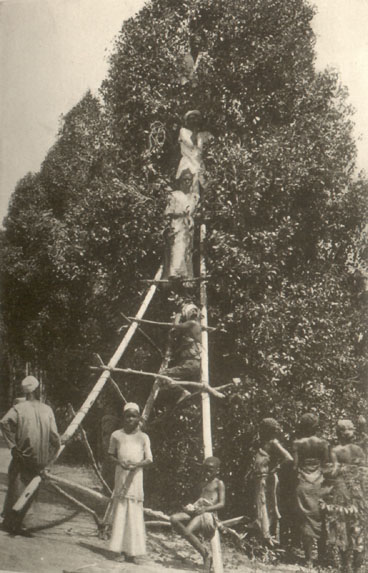

But occasionally I would play some prank on my own account. Once, soon after our removal to Bet il Watoro, I risked my neck in a humorous adventure of the sort. One morning I made my escape, and climbed a tall cocoanut palm as quick as a cat and unaided by a pingu, the stout rope that even expert climbers never dream of dispensing with. Having got half-way up, I impudently began to call down my greetings to the passers-by. What a fright they got into! A group of alarmed individuals collected round the tree, imploring me to come down with all the caution I could muster. It was out of the question to send anyone up for me; in climbing a palm tree, one's hands are fully occupied, and one cannot take care of a child besides oneself. However, I was enjoying myself capitally, and not until my mother appealed to me in heart-broken accents of despair, promising me all sorts of fine things, would I vouchsafe to descend, which finally I did, sliding down with great deliberation, and reaching the ground in safety. That day I was everybody's pet; presents were showered upon me to celebrate my fortunate deliverance from danger, though I really deserved a severe flogging. We were always playing some trick or other, no punishment deterring us from the continuation of our naughtiness. There were seven of us, three boys and four girls, who kept the house lively, and often, alas, got our poor mothers into trouble.

Now and then my dear mother kept me at home on some other day than Friday, which opportunities the indulgent Majid seized upon to spoil me thoroughly. It was on one of those occasions that he gave us a terrible fright. He was subject to frequent cramps, whence he was rarely, if ever, left unattended. Even if he took a bath, my mother and Chaduji, whose confidence in the servants was limited, took it in turn to watch at the door, exchanging a few words with him from time to time, when he would indulge in his favourite pleasantry of exclaiming "I am still alive!" Thus Chaduji, while walking to and fro outside the bathroom door one day, suddenly heard a heavy thud inside. Entering, in great perturbation, she found my beloved brother on the floor, in the throes of a violent attack — the worst he had ever suffered. A mounted messenger was at once despatched to Bet il Mtoni, to summon my father.

From their ignorance about diseases in general, the people of Zanzibar are dupes of quackery; indeed, now that I am familiar with the natural and rational treatment of diseases by competent doctors, I feel tempted to believe that many deaths at home must have been due to barbarous medical methods rather than to sickness.

Unfortified with that adamantine faith in our "destiny," I hardly know how we should have supported our grief over the numerous deaths among our family and retainers. Poor Majid, who lay unconscious for hours in his spasms, was obliged to breathe air which would have been injurious to the healthiest person. Despite our great indoor love of free, fresh air, an invalid, especially if suspected of visitation by the Evil One, is rigidly secluded from the outer atmosphere, and his room, as well as the whole house, vigorously fumigated.

The Sultan landed about an hour after Majid's seizure in a mtumbi, a tiny fishing boat holding only one person. He hastened to the house, and though the parent of more than forty children was passionately affected by the illness of one. Bitter tears coursed down his cheeks as he stood at the sick bed, crying out aloud "Oh, Allah, oh, Allah, preserve my son!" Thus did he pray without ceasing. The Most High listened to his petition, and Majid was restored to us.

When my mother questioned the Sultan as to his reason for coming in such a miserable craft, he replied: "At the moment the messenger arrived, there was not a boat of any kind ready on the shore, and none could have been obtained without first being signalled for. I had no time to spare, and did not even want to wait for a horse to be saddled. Just then I happened to catch sight of a fisherman in his mtumbi close to the benjile; I hailed him, caught up my arms, jumped in, and made off immediately." Now you must know that a mtumbi is nothing but the trunk of a tree hollowed out, is supposed to hold but one, and is propelled by a double paddle instead of oars. Narrow, short, and pointed at the bow, it therefore differs from what is known in Germany as the "Greenland canoe." In this country too it must sound strange that a man plunged into anxiety about his son's life should yet think of his weapons. Well, customs vary all the world over. As to the European the Arab's fondness for his arms is incomprehensible, so the Arab mind has much difficulty in understanding some of the Northern usages. Just now the awful toping by the male sex occurs to me as an example.

Thus I went to school every day at Bet il Sahel, returning each evening to my mother at Bet il Watoro. After having learnt about a third of the Koran by heart, I was supposed to have done with school, at the age of nine. Thenceforth I repaired but on Fridays to Bet il Sahel — my father's day there — in the company of my mother and Chaduji.

We went on living contentedly in this way at Bet il Watoro for two years. But good times cannot be expected to last; usually some unforeseen and untoward event disturbs one's peace. So in our case.

The cause of strife in our household was a creature than whom none could have been more charming and lovable. Assha, a distant relative of ours, had recently come from Oman to Zanzibar, where she was soon taken to wife by Majid. We were all devoted to her, and all rejoiced over Majid's happiness, with the single exception of his sister Chaduji, who, I deeply regret to confess wronged Assha entirely, from beginning to end. Assha, I have remarked, was in every respect charming; besides, she was quite young, so that Chaduji ought to have instructed her, and by degrees have imparted dignity to her. But she treated her with scorn and enmity. Her marriage to Majid entitled Assha to first place in the household; nevertheless, Chaduji patronised her so that the poor, gentle soul would go weeping to my mother, to complain of this unwarranted treatment. My mother's situation between two fires, as it were, became most difficult and unenviable. Chaduji declined to surrender any of her imaginary rights, and continued to look upon Assha as an irresponsible child. In vain did my mother endeavour to rectify her views, and to make her recognise the position of Majid's wife; in vain she besought her to spare Majid whatever annoyance she could, for his own sake. Yet it was all done in vain. Our once agreeable existence at Bet il Watoro became unbearable, and in order to escape from a scene of perpetual discussion my mother decided to leave the house she liked so well.

Majid and his wife would not hear of her departure, Assha being quite inconsolable; Chaduji, on the other hand, remained unmoved, which served to strengthen my mother in her resolve. Assha herself at last felt she could put up with Chaduji's autocratic ways no longer, and obtained a divorce from Majid. The poor thing took her wretched experiences in Zanzibar so to heart that she would none of the country or its inhabitants. Under favour of the south wind she sailed back to Oman, where she had an aunt living in the neighbourhood of Muscat, the capital, both her parents having died. As for my mother and me, our removal had been planned for some time, and we migrated to Bet il Tani. My sister Chole was delighted, as we now were almost under her very roof; she in fact secured and arranged our new quarters for us.

The Sultan's houses were all so crowded that it was no easy matter to get rooms, and gradually a habit had arisen of counting upon vacancies through death. It was really abominable to see a woman prick up her ears at another woman's cough, as if hoping for a case of consumption. Sinful as such thoughts must appear, they were of course due to this overcrowding. My mother and I owed it to Chole that we got a fine, large room at Bet il Tani without having to wait for somebody's decease. Chaduji we rarely saw now; she felt insulted by our change of abode, and accused my mother of lack of affection for her, quite wrongfully, to be sure. But my mother had simply been unable to endure Chaduji's oppression of the girl whose chief offense was having become Majid's wife. He continued to visit us, however, and to remain one of our best friends.

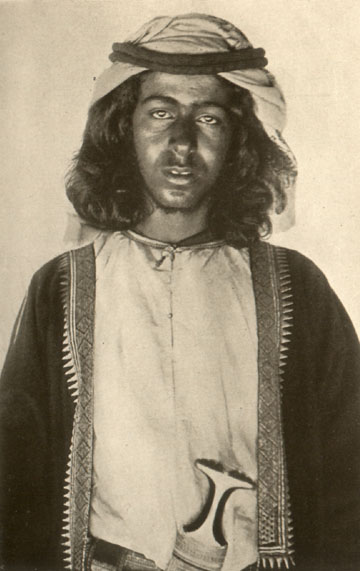

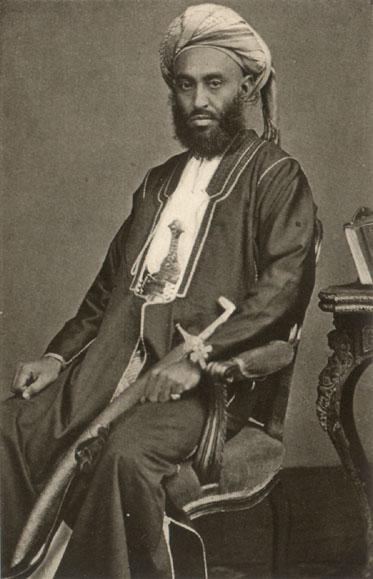

|

| Photograph by Mr. Samuel Zweeren |

| TYPE OF OMAN ARAB |

Bet il Tani was situated in immediate proximity to Bet il Sahel, and was connected with it by a bridge that passed over a Turkish bath-house midway between the two. At the time I speak of Bet il Tani presented but a shadow of its former splendours. On its first story there had once lived a Persian princess, Shesadeh by name. She was one of my father's principal wives and a great beauty. Said to have been enormously extravagant, she nevertheless had the reputation of great kindness toward her stepchildren. A hundred and fifty Persian horsemen, who occupied the ground floor, formed her modest suite; she rode and hunted with them in the open light of day, which, according to Arabian notions, was going rather too far. The Persian women seem to receive a sort of Spartan education; they have a great deal more liberty than ours, but are coarser both in thought and behaviour.

Shesadeh, I was told, had led a most luxurious life. Her clothes — Persian style — were literally stitched with genuine pearls from top to bottom; if a servant, sweeping the rooms, found any on the floor, the princess would always refuse to take them back. She not only made desperate inroads upon the Sultan's bounty, but transgressed against sacred laws. Marrying my father for his wealth, her heart was bestowed on another. The Sultan went nigh to incurring blood-guiltiness one day, in the heat of his anger, when a faithful attendant stayed his arm, saving Shesadeh from death and my father from a dreadful sin. Nothing but divorce was possible after that; fortunately the union had been childless. Some years later the Sultan was fighting the Persians at Bender Abbas, on the Persian Gulf, when, it was reported, the handsome Shesadeh was observed with the hostile forces, aiming at members of our family.

In that princess's erstwhile home I began to learn writing on my own account, and after a very primitive method. Of course this had to be done in secret, as women are never taught to write, and any knowledge they may acquire of it must not be discovered. For a first lesson I took the Koran, and tried to imitate the characters on the shoulderblade of a camel, which in Zanzibar does duty for a slate. Success inspired me with encouragement — I made quick progress. But eventually I needed some guidance in caligraphy proper, so I imposed upon one of our "educated" slaves the huge honour of acting as my writing master. Somehow the affair came to light, and torrents of obloquy descended upon me. But not a rap cared I!

CHAPTER V

NATIONAL SINGULARITIES

THE VAUNTED ACTIVITY OF NORTHERN PEOPLES — INFANT DRESS — A CLIMATE FAVOURING EASE — PRAYER FIVE TIMES A DAY — INTERVENING PURSUITS — CHEWING BETEL — GOING TO BED — MENU À LA ZANZIBAR — REAL COFFEE

OVER and over again I have been asked: "How on earth do the people manage to exist in your country, without anything to do?" And the question is justifiable enough from the point of view of the Northerner, who simply cannot imagine life without work, and who is convinced the Oriental never stirs her little finger, but dreams away most of her time in the seclusion of the harem. Of course, natural conditions vary throughout the world, and it is they that govern our ideas, our habits, and our customs. In the North one is compelled to exert oneself in order to live at all, and very hard too, if one wishes to enjoy life, but the Southern races are greatly favoured. I repeat the word "favoured" because the frugality of a people is an inestimable blessing; the Arabs, who are often described in books as exceedingly idle, are remarkably frugal, more so perhaps than any but the Chinese. Nature herself has ordained that the Southerner can work, while the Northerner must. The Northern nations seem to be very conceited, and look down with pride and contempt upon the people of the tropics — not a laudable state of mind. At the same time they are blind to the fact, in Europe, that their activity is absolutely compulsory to prevent them from perishing by the hundred thousand. The European is obliged to work — that is all; hence he has no right to make such a great virtue of sheer necessity. Are not Italians, Spaniards, and Portuguese less industrious than Germans and Englishmen? And what may the reason be? Merely that the former have more summer than winter, and consequently that they have less of a struggle for existence. A cold climate implies the providing and securing oneself against all sorts of contingencies and actualities quite unknown in southern lands.

Luxury plays the same part everywhere. Who has the money and the inclination will find opportunity to gratify his fancies, whatever quarter of the globe he may inhabit. So let us leave this subject untouched, and confine ourselves to the real necessities of life. If in this country the new-born infant requires a quantity of things to protect its frail existence against the perversities of a changeable climate, the little brown-skinned Southerner lies almost naked, slumbering easily while fanned by a perpetual current of warm air. If in Germany a two-year-old child needs shoes, stockings, pantalettes, a couple of petticoats, a dress, an overcoat, gloves, scarf, gaiters, muff, and a fur cap, whether it belongs to a banker or a labourer — the quality being all that differs — in Zanzibar the costume of a royal prince of the same age comprises two articles, shirt and cap. Then why should an Arabian mother, whose demands for herself and child are so small, work as hard as a German housewife? She has never heard of darning gloves and stockings, of performing the sundry labours done for a European child once a week.

A certain great institution of European households we are ignorant of — washday. In Zanzibar we wash every day whatever needs washing, and in half an hour's time the things are all dry, pressed (not ironed), and put away. We also dispense with curtains, which besides being troublesome and keeping out the sunlight, have to be kept clean and in repair. An Oriental woman, whatever her rank, tears her clothes to a surprisingly limited extent, which is natural enough, since she does not move about so much, frequents the public thoroughfares less, and possesses fewer garments.

All these, and several other considerations help to make the Oriental woman's lot more bearable and comfortable than the European's, without particular regard to social station. But in order to be familiar with the details of their daily life one must have spent some time among them. Tourists, who make only a brief sojourn in those parts, and who, perhaps, get their information from waiters at hotels, are scarcely to be considered as credible witnesses. European ladies who may actually have penetrated into a harem, perhaps in Constantinople or in Cairo, are still unacquainted with the real harem; they have only known its outer semblance in the rooms kept for show, rooms where European finery is partially aped. Besides, the climate is so generous and beneficent that one hardly need trouble about the morrow. I do not deny that the people down there are disposed to taking things easy, but remembering the heat of July and August in Europe, one may conceive what sort of effect the tropical sun would have upon one.

The Arab has no leaning toward commerce and industry; he cares for little else than warfare and agriculture. Few Arabs take to a special trade or profession; they make indifferent merchants, though much given to bartering; the Semitic sense of business they appear to lack. His frugality enables the Arab to make ends meet easily, and as a rule he thinks only of the immediate present. He never plans for the distant future, for he knows that any day may be his last. Thus the life of the Oriental glides smoothly and easily along. Still, I now am describing only the life in Zanzibar and Oman, which in various respects differ from other Eastern countries.

The Mahometan's day is regulated — if that is not saying too much — by his religious devotions. Five times a day does he bend the knee to God, and if he properly performs all the contingent ablutions and changes of raiment in accordance with scriptural ruling, fully three hours will be consumed. The rich are awakened between four and half-past five for the first prayer, after which they return to bed, but the common people begin the day's work with their first prayer. In our establishment, where hundreds of inmates tried to follow their individual tastes, it was hard to maintain fixed rules, although the two general repasts and the devotions compelled a measure of systematic order. Most of us, then, slept on again until eight o'clock, when the women and children were roused by a gentle and agreeable kneading process, at the hands of a female servant. A bath of fresh spring water was ready, and likewise our wearing apparel, strewn the night before with jessamine or orange blossoms, and now scented with amber and musk. Nowhere in the world is the cold bath used and appreciated more than in the East. After dressing, which usually took up an hour, we all went to see our father, to wish him "good morning," and then to partake of the first meal. To this we were summoned by a drum, but as the table was completely set beforehand, much less time was occupied in eating than the European method demands.

It was then that the day's real activities opened. The gentlemen prepared for the audience chamber, while the ladies — who were not obliged to work — took seats at their windows, to watch the passing in the street below, and to catch such private glances as might occasionally be thrown up at them. This provided great amusement; only sometimes a cautious mother or aunt would contrive to coax one away from the coign of vantage. Two of three hours thus sped quickly by. Visits were meanwhile being exchanged among the gentlemen, the ladies sending out servants with verbal appointments for the evening. Sedately minded persons, however, went to their airy apartments, where, either alone, or in small groups, they did needlework, stitching their veils, shirts, or trousers with gold braid, or a husband's, son's, or brother's shirt with red or white silk, which needed particular skill. The remainder would read stories, visit sick or well friends in their rooms, or attend to other private affairs. By this time it was one o'clock. Servants came to remind us of the second prayer. The sun was at its height then, so that everyone was glad to open the early part of the afternoon reposing, in a thin, cool garment, on a soft, prettily woven mat with sacred inscriptions worked upon it. Between dozing, chatting, and nibbling at fruit or cake, the time passed very pleasantly until four o'clock, when we prayed for the third time; a more elaborate toilette followed, and we repaired again to the presence of the Sultan, to wish him "good afternoon." The grown-up children were allowed to call him "father," but the little ones and their mothers had to address him as "Sir."

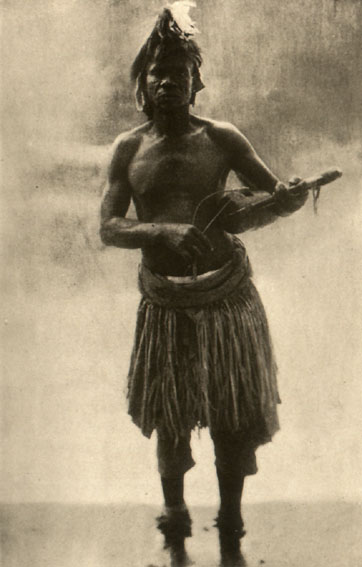

Now came the second and last meal of the day, at which the family would assemble. Upon its termination, the eunuchs would carry European chairs out upon the broad veranda, but only for the adults; the small people stood up as a mark of respect for age, which is held in greater reverence there than anywhere else. The family gathered about the Sultan, while a row of smart, well-armed eunuchs lined the background. Coffee was passed round, as well as beverages prepared from the essence of French fruits. The conversation was accompanied by a stupendous barrel organ, the biggest I ever saw; by way of change one of the large music boxes would be set going, or a blind Arabian girl named Amra, who was gifted with a lovely voice, would be ordered to sing.

In about an hour and a half the family separated, each following his or her own devices. Chewing betel was a favourite pastime. It is a Suahili habit, so that the Arabs of Arabia Proper find no pleasure therein; but those of us born on the east coast of Africa, and brought up among Negroes and mulattoes, took to the habit quite readily, in spite of derision from our Asiatic relatives. We chewed betel surreptitiously, however, while absent from the Sultan, who had forbidden the practice.

With the aid of miscellaneous diversions the brief space slipped by till sundown, announced by musketry fire and drumming on the part of the Indian guard. This also constituted a signal for prayer. But the fourth observance was the most hurried of the day, since everybody not intending to pay visits would be expecting guests at home — sisters, stepmothers, stepchildren, secondary wives. For entertainment there was coffee and lemonade, cakes and fruit, jesting and laughing, reading aloud, playing cards (but not for money or any other stake), singing, listening to the sese being played upon by a Negro, sewing, stitching, lace-making — just as one felt inclined.

So it is altogether wrong to suppose that the rich Oriental woman has nothing to do. True, she neither paints, plays the piano, nor dances (as understood here). But those are not the only existing methods of passing the time. Down there we are all contented; to us the feverish, everlasting chase after new pleasures and enjoyments is quite foreign. From the European point of view, therefore, the Oriental might no doubt be looked upon as a Philistine.

|

| Photograph by Mrs. Emma Shaw Colcleugh |

| NATIVE MUSICIAN |