THE SOUDAN.

CHAPTER I.

VOYAGE OUT.

MY STEP-DAUGHTER AND MYSELF START FROM ENGLAND – PASSENGERS ON BOARD – ALGIERS – RITUALISTIC AND LOW CHURCH CONTROVERSY – MALTA – ITS CHURCHES – GOVERNOR'S PALACE – DIVERS – NEWS OF DISASTER – PORT SAID – NEWS FROM MY HUSBAND – TAKEN OFF BY THE GENDARMES – CAFÉ CHANTANT – POST-BOAT IN CANAL – ISMAILIA – ANECDOTE OF LATE KHEDIVE'S A.D.C. – MARKS OF BRITISH OCCUPATION – LINES OF TEL-EL-KEBIR – THE EGYPTIANS PLOUGHING – DRAWING WATER – ZAGAZIG – ITS MANUFACTURES AND STATION – FIRST VIEW OF CAIRO – MEET MY HUSBAND.

AS the cholera epidemic had passed away in Egypt, and it was considered quite safe to return there, my step-daughter and myself took passages by the British India line of steamers, and on the 14th of November, 1883, started from the Royal Albert Docks, in the Eldorado. I must say, she was not a good specimen of the line, for she was very dirty, and the food was very badly cooked. The saloon tables were decorated with an attempt at finery, in the shape of artificial flowers of every description, and these, though good of their kind, failed like all shams. The waiters were all natives of India, as is usual with lines plying to the East. Consequently, until they put on their own white native costume at Malta, they looked excessively dirty and miserable. It was a very fine day at starting, but as we approached the Isle of Wight it got so very foggy that the steamer nearly ran aground there. The sea was, however, comparatively calm, thus allowing the passengers to make each other's acquaintance from the beginning. Principal amongst them was Mr. Plimsoll, M.P., his daughter, and a friend, who were going to Calcutta; a Major and Mrs. Empson, and about twenty others, proceeding to other places in India. We caught it, though, on reaching the Bay of Biscay, for we came in for the roll left by a big Atlantic storm. This made every one disappear below; and, indeed, we were very uncomfortable until we got into the Mediterranean.

20th. – What a contrast it is to-day, to the cold, damp weather in England which we have only left six days ago! Here, in view of Algiers, with its Oriental buildings glowing in the rays of a Southern setting sun, the bright hues of the Mediterranean Sea, so completely in harmony with the gorgeous scene, making everything so bright, peaceful, and quiet, it seems hard to believe that little more than a hundred years ago this picturesque town was still the seat of a pirate horde. But here are four bells striking, and the dinner-bell going, so we must rouse ourselves from our reveries and return to everyday life.

On the 21st we passed the island of Panteliari, one of those volcanic productions of the Mediterranean, which even now are growing up, rising, and disappearing. The town on the island is made up of square, flat-roofed houses; they are invariably whitewashed, and therefore give the appearance, in the distance, of a lot of tombstones, the vegetation being so scarce that it does not take way from this effect.

A very amusing story has just been told me, relating to the controversy between a swell and very advanced Ritualist, and a by no means clever, but very determined member of the Low Church. These two were sitting opposite to each other at dinner, when the Ritualist happened to observe that they always had matins in his church. The other immediately pricked up his ears at this, and taking it as a challenge, shouted, much to the amusement of the company, "Why, mats, only mats! We have in our church, kamptulicon right up to the altar!"

We arrived at Malta at 5 a.m. the 23rd of November, and, passing the splendid lighthouse of St. Elmo on our right, and port Ricasoli on our left, anchored close to the Custom-house. The captain having told us the ship was to remain until the afternoon, everybody hurried off to the town. Our party landed at the steps and walked on to the square in front of the Government-house, to enjoy fresh bread and butter, and good coffee – a luxury we had so long been deprived of. After that we visited the Church of St. John, which, crowded as it is with remembrances of the old Knights of Malta, in the shape of various relics of that time, and the chapels to the different nations situated on either side of the aisle, brings vividly back to one's mind the romantic history of their struggles with the infidels. Besides the above the most remarkable things are the following: – In the Portuguese chapel a group of statuary, representing Charity and Justice, by Mariano Gavano, a Maltese sculptor, who died in France. He has also another group behind the altar, supposed to be his masterpiece, and especially remarkable as being carved out of one block of marble. The subject is the Baptism, of our Saviour by St. John. In the French chapel the sculptured figure on the tomb of the Comte de Beaujolais, brother of Louis Philippe, representing him as having fallen asleep on the camp ground, is very good. The artist was an Italian. In the Italian chapel was a very fine picture by Michael Angelo, representing St. Jerome studying a book. An extremely interesting portion of the church is the marble flooring, inscribed with the arms of the various knights of the order who are buried below. Every great family of Europe has its representatives, and it would be in the highest degree interesting to study their various histories, I fancy many a book more than vieing with even the best of Sir W. Scott's could be made out of the materials so gathered; but we have no time to examine them all, and so go on to the solid silver gates at the entrance to the Irish chapel, though, after all, these have very little effect, as the brown painting with which the silver was coated in order to give them the effect of bronze, and thus to prevent the French soldiers looting them, still remains.

After leaving the Church of St. John, we went to the market, a very dirty and not at all interesting spot, with nothing much to be got there but Mandoline oranges, not yet ripe enough to be good eating. From the market we went to the Governor's palace, where there is a very fine ball and council room. The walls of the latter were covered with tapestry eight hundred years old, representing the four quarters of the globe. We also saw, in the same room, several chairs, including the Grand Master's, all relics of the Knights of St. John. Passing on, we came to the armoury, filled with old armour that had belonged to the same knights. On the walls of this room, were the colours of the 63rd and another regiment, looking strangely out of place amongst all this armour, for somehow one expects old colours to be put away in some church, and not in a store like this. Inside the courtyard of the palace was a lovely garden, filled with large trees, and looking all the brighter for the want of anything of the kind in the rest of the town. There was a very large poinsettia in full blossom, also orange trees with plenty of oranges on them, and a lovely bougainvillea in full flower, climbing up the west wall. I saw also a blue ipomæa on the opposite side. Flowers in Malta are very cheap, and we were offered a large basket of roses and heliotrope for a shilling. I bought a large bunch for a penny, and they lasted three days on board ship. Time passing, we had to put an end to our roamings and return to the ship, which sailed soon afterwards.

While waiting to start, we had an opportunity of seeing the wonderful diving powers of the Maltese, who, helped by the clearness and buoyancy of the water, rapidly pick up the shillings and sixpences that are thrown down, before these have sunk to any depth. They showed their real powers by diving under the ship from one side to the other without any apparent difficulty. It is evidently a regular trade, and the divers get very sharp about it, as they will not go down for anything but silver. They know the glint of the latter very well, and though a gentleman on board threw down a well-burnished farthing, no one would go after it, for all knew that none of the passengers would throw them gold. The clanging of the bells is another curious circumstance. The Maltese have a superstition that this ringing drives away the devil, so they go at it as fast as they can, without reference to time or tune. By-the-by, this is just the contrary to the Mussulman idea, who think that ringing brings the devil, and therefore have no bells in their mosques, but call to prayers by means of men shouting from the minarets. The Maltese themselves do not as a whole bear a very good character, though a great many work very hard indeed, and become respectable members of society; but there is no doubt the scum of the Mediterranean population is composed of Maltese, Southern Italians, and Greeks, and it is notorious what a very bad scum this is. They are exceedingly superstitious and very vain. An amusing instance of the latter quality occurred on the occasion of a grand public dinner which was given here to the officers returning from the Crimea. One of the officers of the Malta Fencibles, rising, proposed the toast of "Malta and England," adding that as long as they were allied together, they could face the whole world.

Before leaving the island we heard the great and unfortunate news of the defeat of General Hicks's army in the Soudan, and the total massacre of his troops. This news much excited us, for we thought it might have some effect on my husband's future movements. From to-day, the 26th, we were enabled to sit on deck and enjoy the warmth. It really seemed to give one new life, and we enjoyed it all the more because, while basking in this lovely sunshine, one's thoughts recurred to the climate that we had just left. After leaving Malta we did not see land until we arrived at Port Said, on the 28th of November at 5 a.m., when we were awoke by the whistle of the boat making a great noise; so, despairing of getting any more sleep, especially as there were several other boats whistling at the same time, we got up, dressed, and went on deck, and amused ourselves by watching the busy life around us.

I was expecting news of my husband, and, none coming, got impatient and sent him a telegram saying I had arrived. At about 12 o'clock, the Comte de Montjoie, who was commanding the police at Port Said, came on board, introduced himself, and gave me a letter from my husband, who wrote that on account of the preparations for the war he could not meet me, and that the Comte de Montjoie would do all that was necessary. Accordingly the latter returned to the shore to send off boats with two or three of his men and his brigadier, who took entire charge of the boxes and ourselves too. We were very much chaffed by the passengers, who said we were being taken off by gendarmes, but it was a great comfort, and very pleasant having everything done for us. When we arrived at the hotel, our room and luncheon had been ordered at the only good hotel there, the "Pays Bas."

In the evening Mr. Burrel, the English Vice-Consul, took us to the great Café Chantant, a place kept up most respectably, though greatly on the proceeds of a rouge-et-noire table belonging to the house. Major Shakespeare, of General Wood's army, Mr. Baker, Consul for Khartoum, and the Comte de Montjoie also came with us. All the principal people have their regular seats; in fact, it is almost a theatre. A rather good actress was there that night, and she raised a furore by singing the "Marseillaise" with great entrain, the greater part of the audience being French troops on their way to Tonquin, who had just come in by a French troop-ship. What delighted these soldiers most was the compliment she paid to their country by coming on to the scene, wearing three ribbons across her dress, arranged according to the French colours.

The applause was deafening even at the very first, and when she finished her song, it was repeated over and over again. One reason for staying so late was the inconvenient hour the postal launch starts down the Canal, viz. midnight, and it was only after a good deal of trouble that, getting the baggage to the wharf, we started with several other passengers, all crowded up in a small saloon. We might have stayed till next day, but were in a hurry to see my husband, for we were much startled by hearing he would have to go to the Soudan almost immediately.

What a night we had of it! The seats were narrow; the people were many of them foreigners, who would try and shut out all ventilation; the sides of the cabin were straight up, and so gave no rest to one's back; and we had to go on all night, not arriving at Ismailia till nearly 7 a.m. At that place there is a rather nice little hotel close to the water, but by mistake we passed it, and went on to a small French one, where luckily they gave us a decent breakfast, and at 11 a.m. got into the train for our final day's travel.

Before quite leaving off all notice of the great salt-water Canal, I could not help thinking what a splendid instance this was of the late Khedive's power of will, and how lucky it was for the world he had this will, for without him the Canal could not have been made. It is as well not to look too closely at the history of its construction, nor the lives lost over it, amounting to hundreds of thousands. The Bulgarian atrocities did not cause more misery. The poor wretched gangs of fellahs starved and driven by the Koorbash to work to their last gasp, present an awful picture of misery that is almost too painful to think about in spite of the great results obtained. His magnificent extravagance is well exemplified in the small palace he built for the Empress Eugénie, and which has never been occupied since. Here, too, an instance of thorough Oriental arbitrariness occurred. The Empress, while thanking the Khedive for the magnificent reception he had given her, happened to say that the only thing she had not seen was an Arab marriage. "Indeed," said the Khedive, "this shall soon be remedied." So he sent for his A.D.C., gave him one of his Circassian slaves from the harem, presented him with a large dowry, and told the astonished official that everything was to be ready in two days. Accordingly, on the second day there was a grand marriage à l' Arabi. The Empress was greatly pleased, and the A.D.C., a man far more European than Egyptian, and who spoke several European languages, splendidly found himself indissolubly attached to a Mahomedan wife, while all along it had been the dream of his life to marry a European lady, one educated like himself, and with whom he could associate. But he knew he dared not refuse, and so an accident settled his whole future life.

While going out of the Ismailia station our attention was attracted to the marks of the late English occupation, in the shape of notices written on the walls of various buildings, to the effect of this being the bakery, that the artillery store, another the commissariat, etc. From what we saw of the place, one cannot but come to the conclusion that the French manage to make up a much neater town than we do. The roads are all at right angles to each other, very well kept, and there are small and pretty public gardens in the centre; not only that, but the native town, equally straightly laid out, was kept, with all its stinks, well away from the European quarter. To get to Nefish one has to cross a large fresh-water canal, and on it we saw our first diabeah. I was rather interested in this, as we were to have lived in one at Cairo. From this station the rail runs through the desert, nothing but sand the whole way until just before we got to Tel-el-Kebir, where cultivated ground steadily begins to dominate. Coming up to this latter place, there were all along the route unmistakable signs of the passage of English troops, in the shape of empty meat-tins of every kind, bits of telegraph wires strewed about, the little well-known fireplaces of the Indian troops, broken crockery, and even bits of paper blowing about. From the train a very good sight is obtained of the lines of Tel-el-Kebir. They stretch right and left on either side of the railway, and do not seem to be very formidable, owing to the want of what military men call flank defence. The cemetery, where are buried those of our troops who fell there, is close to the station, and though the trees and flowers have only been planted a very short time, yet their extraordinary growth proves how fertile the so-called desert is when it is watered even a little.

It is curious to observe how defined the line is between the rich green cultivation and the barren yellow desert. The only kind of trees of any size are the graceful date palms, which have no foliage to hide this boundary. Signs of the rise of the Nile strike one everywhere; the canals are all full, and the water is being let into the fields in that careful and methodical manner for which the Egyptian fellah has always been famed. He works with the same instrument as his forefathers, the same old wheel at the well turned by the patient buffalo; he has the same way of raising water by lever and weight, or else by men standing on either side of a small water-hole, lifting up the water with a wretched old palm-leaf basket. Nothing seems changed from what one remembers to have seen drawn in the sketches of their oldest monuments. There is, however, a very great want of cattle, owing to the disease and the exigencies of the late war. Camels and donkeys or camels and buffaloes are constantly seen harnessed together, the wretched camel looking intensely miserable, and as if he would like much to make them understand that his business was to carry, and not to draw. We soon had to give up observing the country, and shut up the windows tight, as the dust got so troublesome; and we amused ourselves in the best way we could until we got to Zagazig, where we had lunch – a meal for which we paid greatly and got very little. Zagazig is the most important junction in Egypt. It is at this place that all the principal railways of the country meet. The town itself is inhabited by a considerable number of Europeans, and there are several manufactories. Others were in the process of construction; but the late war stopped them all, and the English occupation, instead of increasing business, seems to diminish it still more – at least, so the inhabitants declare.

Near here there is a very ancient city, the traces of whose existence are lost in the dim mists of past ages, but it is so ruined, and tradition is so still about it, that only the most learned antiquaries find interest in it. The station was crowded with all sorts of people – Jews, Greeks, English, French, Italians; Mussulmans of all kinds, Turks, Egyptians, and Arabs, the two latter distinguished by their dirty appearance; women with their faces covered up; children howling, their eyes filled with flies; – indeed, specimens of all tribes and races, clean and unclean, which it would take me longer than the time the train stops at the station to notice specially. The constant passing of passengers and tourists makes the boys and hangers-on at this station a set of most impudent beggars; they are always on the look-out for backshish, and keep putting their heads in at the carriage window, shouting for something.

After leaving Zagazig and approaching Galloub, the first sight of the citadel of Cairo is got, and soon after the Pyramids come into. view; trees also get larger and more numerous – indeed, so much so that people say that the climate is in consequence beginning to change and become more damp. If such is the case, good-bye to many of the monuments of old, such as mummies, etc., which have only been preserved through all these long ages owing to the intense dryness of the desert air. What a pity that would be! But there was no time then to think of these things, as we were fast approaching Cairo, and we could already see the railway buildings that had been blown up during the time of the British occupation, owing to a train-load of shells and ammunition taking fire. At the station itself we were met by my husband, who, by way of greeting, informed us that he was off to the Soudan the next day, and that if we wanted to see anything of him we must go with him to Suakim. This was, indeed, anything but pleasant news, though of course we made up our minds at once to go with him; fortunately, we had no time to think, but had to hurry off to our house in the Shoobra Road.

CHAPTER II.

CAIRO.

EGYPTIAN WATCHMEN – OUR HOUSE – SHOOBRA ROAD – CATHOLIC CONVENT – CELEBRATED GARDENS OF CICOLANI – FASHIONABLE DRIVE – THE KHEDIVE – SIR EVELYN BARING – A VISIT TO GENERAL BAKER – SHEPHEARD'S HOTEL – GENERAL BAKER'S DIABEAH – PARTY TO THE PYRAMIDS – THE HOWLING DERVISHES – SUPERSTITIONS OF THE EGYPTIANS – COPTIC CHURCH – EGYPTIAN FLIES – CITADEL – DONKEY-BOYS – VIEW OF CAIRO AND THE SURROUNDING COUNTRY FROM THE CITADEL – HOUSES OF EGYPTIAN FELLAHS – BOULAK MUSEUM – DISCOVERY OF PHARAOH OF THE BIBLE – CAIRO DOGS – TURKISH GENDARMERIE REFUSE TO GO TO THE SOUDAN – PARADE BEFORE THE KHEDIVE – EXTRAORDINARY SCENES AT THE STATION ON DEPARTURE OF TROOPS – OUR SERVANTS – MY HUSBAND HAS AN AUDIENCE WITH THE KHEDIVE – VISIT TO THE VICE-QUEEN – THE ESBEKIAH RESTAURANT – TRAIN GOES OFF WITHOUT US – THE WOODEN ARMY – MR. CLIFFORD LLOYD'S IDEA OF THE HOPELESSNESS OF ANYBODY COMING BACK SAFE – OUR DEPARTURE – THE BITTER LAKES – THE EGYPTIAN POSTAL STEAMER ZAGAZIG.

WE had intended to sleep late, as we were tired, but, although the shouting of the Gaffirs, or watchmen, and the occasional howl of one of the many dogs about, prevented us from having an altogether undisturbed night, we were thoroughly awoke in the early morning by men driving camels and donkeys, coming in laden with grass and vegetables, and who made so much noise that we were obliged to get up, in spite of still feeling the fatigue of the previous day; but when once out of bed, the delightful clear atmosphere, the fragrance of the flowers, and the newness of the place made one forget the troubles of the night.

The first thing we did was to look over our house. It is a very large, square-built one, with a splendid big marble hall on the ground-floor, and an equally fine granite staircase communicating with the upper floor. A fine date-palm tree looks in at the big window half-way up the staircase. Upstairs there are six large rooms, besides smaller ones, all eighteen feet high, and therefore thoroughly suited for the summer heat. The drawing-room is furnished with Indian furniture, while my boudoir was arranged to suit the very pretty Zanzibar grass-cloth curtains my husband had brought from Aden. One special piece in this room that was always admired was my writing-table, made of teakwood in the old Saxon style, by Wimbridge of Bombay. There is a large balcony in the front of the house, looking on to the Shoobra Road. It is along this latter that the Khedive drives twice a week, and in consequence every one else does the same thing! On account of the water of the Nile having permeated everywhere, our garden was not yet in a state to walk in; but it will look lovely later on, for it is full of poinsettias, honeysuckle, oleanders, orange trees, etc. I must not forget the date trees, and also the luxuriant vine, which covered the picturesque well in the centre of the garden. Close to us is the Catholic convent, where an excellent education is given at a very cheap rate; a little beyond is the celebrated garden of Cicolani, a rich draper of Cairo. He made up this garden, and built a splendid house in the midst of it, in hopes that Ismail Pasha, late Khedive, would buy it; but he rather over-shot his mark, by putting such a price on it that even Ismail Pasha, much as he liked new buildings, drew off.

The drive into the garden is along an avenue branching off from the Shoobra Road. For this bit of ground, about 300 yards, Cicolani, they say, had to pay £10,000, for it appears that when he originally bought the property there was no road leading up to it from any regular thoroughfare, and Cicolani was too much employed building his palace and making up his garden, to think about that. The consequence was, that when he came to bargain with the owner of the land along which the avenue now runs, the aforesaid owner had already seen how impossible it was for Cicolani to do without it. Poor Cicolani had, therefore, to pay this exorbitant price. But whatever the question of money was, the gardens are nevertheless beautifully laid out. The avenue of oleanders during the month of May is a sight not to be seen anywhere else, for they are one mass of double flowers that quite cover up the parent tree. Then, the peculiar climate of Egypt enables many of the northern trees and plants to grow luxuriantly side by side with those of tropical climes, and thus allow of the full charm of variety. Nothing can be more beautiful than the wonderful clusters of purple bougainvillea growing all over a kind of grotto made up of petrified wood, from the celebrated forests of the same. In a little water in front of the grotto is the lotus-flower, a regular Indian plant; while in the shade of some of the petrified wood are several beautiful English ferns. Overshadowing the water bends a graceful clump of bamboos, hardly hiding a group of ash trees which spring straight up behind it. Mixed with all these are beautiful clusters of roses, enormous tropical aloes, palm trees of every kind; while darting through them here and there, and adding life to the scene, are small birds of various colours, pursuing the bright dragon-flies that flit about the water. While, to complete all, the bright, soft radiance of a Southern winter sun diffuses its cheerful influence all round, making one think that here at least perfect peace and happiness is possible. A little past the grotto is another small piece of water, springing from the centre of which is a rockery tastefully covered with ferns, and forming the pedestal to two statues of children, a boy and girl, the boy holding an umbrella over the girl's head; the trees around cover them with a deep shadow, and the tout ensemble is very pretty and shows great taste. We did not go into the house, as it requires special permission from the owner; and, after all, it is only furnished in the gaudy Parisian style. Cicolani himself comes here from his shop, for an hour or so, morning and evening, and when he does sleep here always occupies two small scantily furnished rooms over the stables.

The day after we arrived at Cairo was one of the Shubra gala-days, and everybody drove or rode along it. Let us suppose ourselves on the balcony watching them. To begin with, here are the mounted gendarmes coming to station themselves along the road. They are dressed in blue uniform with yellow facings, long boots, tarbooshes, and mounted on grey horses. Their arms are swords and a sort of long-barrelled pistol in their hands, to which a kind of steel triangle is attached, so as to enable them, in case of necessity, to use the triangle as a butt and fire from the shoulder. These gendarmes appear about 3 p.m. Soon after, a few carriages begin to drive up, containing generally strangers or others who do not quite know the customs of the place. About 4 p.m. the real business begins. Here come, for instance, half a dozen carriages driving wildly up, two of them containing ladies of some harem, the transparency of whose veils invariably is in proportion to the beauty or otherwise of the face underneath. The veil (yashmak) is so thin with some of them that it really does not hide the face at all, but merely slurs over any little defect in the complexion; and undoubtedly adds very much to the piquancy of the eyes, for which these Circassians are so much famed. The yashmak is a sort of double veil. The first brought round the forehead and gathered neatly up behind and on the head; the second, pinned on behind to the first, falls sufficiently in front to uncover the eyes. The common people wear a hideous black thing, hung on to the sort of black silk, or other kind of thick stuff cloth that covers their head, by a kind of nose-guard. Another amongst these carriages belongs to one of the consuls, as we know by the gorgeously dressed dragoman who is seated on the box; the next is loaded with young France out for a holiday, and therefore smoking, shouting, and singing to show how completely they are at their ease. Mixed with these carriages are black eunuchs, riding on splendid horses, dressed up in the latest European fashion, and looking far more important than their masters, who have probably just gone quietly by. The snob of this place is also well represented in the shape of a dozen or so European and native riders, who go rushing frantically about, hoping to show off their horsemanship, while in reality they only scatter mud about the place, stampede the horses, and bring general execration on their heads from the passers-by. Equally a nuisance are the native cartmen, with their long low carts drawn by mules or donkeys, and which they drive in the most reckless manner, as hard as these poor wretched animals can go, for they know that their carts cannot suffer damage, and that therefore every one must get out of the way.

Now it is about five o'clock, and accordingly here comes the Khedive, bowing, right and left, to all those he meets. In olden times the natives, at least, had all to stop their carriages, get out, and stand by them, making the usual salaam till he had passed. Now all this is over; people of course salute, but in a very different manner, and it is evident the power of the Khedive is not much thought of. His escort consists only of a dozen or so of his body-guard, and with him in his carriage is one of his principal aide-de-camps; while behind, in a couple of others, are a few more of his suite. His horses are fine English ones; the carriage is a simple victoria; everything is in the most simple style.

Soon after the Khedive, the English minister, Sir E. Baring, passed, and the drive is at its fullest. It is a curious thing, with reference to this promenade, that people make it a duty to come here on these two special days, when they would find it so much less dusty and crowded on any other. If, as in India, there was some place at the end of the drive where a band played, and people could meet together and have a chat, there would be some sense in it; but, as it is, nothing but the usual obedience to the laws of fashion can account for it. The road itself is very bad, and threatens the strongest carriage-springs; the repair being done with the soft stone quarried from the Mokattem heights, and therefore, within a month of its being laid down, the holes and hollows are as bad as ever. The only pretty part of it are the large trees which line its whole length, and which are being rapidly cut down, and the view being at the end close to the old palace of Shoobra, where a very fine sight of the Nile and the Pyramids in the distance is obtained. Half an hour after sunset the last of the carriages has passed on its way home, and, as we had taken the precaution to give notice to the head of the Gaffirs that we would not allow their shouts close to our house, the whole place is quiet.

In the morning my husband went back to his office, as there was a great deal to do with reference to sending off the troops to Suakim. I will not now anticipate the next chapter, which gives the detail of the forces, but will go on to the incidents of the day. We went to see my husband at the office at 10 a.m. It is in the Ismailia quarter, close to the large buildings which contain the War Office, Public Works and Sanitary Department. Everything was in the greatest bustle, it being extremely important that the troops should go at once. We here saw, for the first time, poor Colonel Abdul Russak, who was afterwards killed at Teb. We then went off and called on General Baker Pasha at Shepheard's Hotel. His daughter, Miss Baker, being very ill, our visit was naturally a short one, but we took away with us the impression of a very kind, quiet-mannered gentleman. Shepheard's Hotel is a regular meeting-place for everybody, and is as much renowned now as it was in the olden time, when there was no railway, and travellers used to be jogged about in those awful vans across the desert. It is on the piazza in front that everybody who wishes to gather news meets of an evening; it is also a most convenient place to watch the passers-by, the road in front being one of the principal thoroughfares in Cairo. At the end of the garden is Cook's tourists' office; a little further on, Seebah, an excellent photographist. In front, under the arcades, are a column of fine shops, containing all that is necessary for travelling. The Esbekiah gardens are also close by. These were got up by Ismail Pasha, who, as usual, did the thing well. A band plays there every day; in hot weather there is an open-air theatre, with an excellent Italian company. The walks are very nicely laid out, and, as a small charge is made for entering, the absolute riffraff is kept out, thus making it a most pleasant lounge. There is also a very good restaurant here, where breakfast, tiffin, and dinner can be had at very good and cheap rates.

In the afternoon we went off to see General Baker's diabeah, which was moored to the banks of the Nile at Gazeerah. The Hermione, as it is named, is a large, long, flat-bottomed boat, the after part of which is entirely devoted to cabins. There were six sleeping-cabins, with accommodation for ten people, a saloon about twelve feet by twelve, and another about twelve feet by eight, a pantry, and servants' cabin. The deck above was covered over with matting, lined inside with chintz, thus making one fine big room. Needless to say, it was beautifully furnished, with carpets brought by the General from all parts of the world, and several pieces of moresque furniture from that famous man Parvis. This latter is a great man in Cairo. His moresque furniture stands quite unrivalled, and it is a real treat to go to his shop. I was disappointed at the view from the boat. Cairo has not the number of minarets and mosques that make Oriental cities look so pretty. We saw nothing but square-built, dirty houses, lending anything but enchantment to the view. Near here is the palace of Prince Hassan, the Khedive's brother, who has only lately been permitted to return to Egypt. His children were driving along the road as we came on shore; they are very pretty and ladylike, and are being educated by English governesses.

Of course, following out the regular routine, we had to visit the Pyramids, and so made up a party to go there, consisting of Colonel Harington, Mrs. Greville Davis, ourselves, and one or two others. We went in two carriages, and on our way passed through the Khedive's grounds at Gazeerah. He has here two large palaces and a very great extent of land surrounded by a big wall. This land the late Khedive caused to be raised to a height of six feet over the usual level, partly to please himself by having dry ground during the rise of the Nile, but principally in order to give work to crowds of his poor subjects who were suffering from the effects of a bad Nile. Immediately outside the gates, towards the Pyramids, is the town of Gazeerah, a most dirty, overcrowded place, which therefore, of course, suffered most severely during the late epidemic of cholera. The road from here runs almost straight to the Pyramids. Nothing worth noticing occurs the whole way along, especially as one's attention is really fixed to lessening as much as possible the effects of the jolting one is constantly suffering from when going along it. The moment you arrive you are surrounded by a crowd of yelling Arabs, who as a rule take regular possession of any sightseers that may happen to come. We fortunately had Colonel Harington with us, who knew the whole place well, and therefore very soon got rid of all these natives but the necessary one or two. The Pyramids and the Sphinx have been so often described that I will not attempt it again here. All that I can say is, that the general impression is one of vastness, unchangeableness, and repose. Bret Harte, in his "Innocents Abroad," gives as good an idea as any I have ever seen described.

On Friday is the day to see the howling dervishes. These wretched fanatics assemble in a mosque close to the old town. They have a leader, who, standing in the middle of a semicircle formed in front of him, repeats one of the ninety-nine names of Allah (God); the others catch it up, go on repeating it, throwing themselves backwards and forwards quicker and quicker till they get perfectly exhausted. Many of those in the circle are very holy dervishes, and therefore have very long hair, and are exceedingly dirty. At each change in the name they get more and more excited, and throw off their superfluous clothing to give themselves increased freedom in their movements. One of them, after a time, advances towards the centre, and, keeping one foot on the ground as a fulcrum, shoves himself round and round with the other. A tom-tom is further used as the excitement flags; but at last physical force can do no more, and they are obliged to stop, and then comes the demand for backshish. The origin of this curious custom is probably the superstition that to every one of the ninety-nine names of Allah a powerful angel is attached; so when a devotee has lived a life pleasing to God, and has repeated one of these names often enough, God orders the angel belonging to that name to become the faithful slave of the above devotee, and thereby enables the latter to be all-powerful in this world. Such is, indeed, the means by which the Mahdi gained his power over the ignorant Soudanese, for he separated himself for eight hours a day for several years, lived in a cave, incessantly shouting only the name of one of those attributes, until at last he obtained the desired power – so, at least, the Soudanese and Arabs believe. Another reason, too, is that each believer is supposed to possess a certain portion of ground in Paradise. Every time this believer repeats certain prayers and goes through the names of Allah, so many trees plant themselves in his possessions there. Should he, therefore, have said his prayers properly, it lies in his power to have a far more magnificent property in Paradise than any of those rich men here below, who have no time or will to pay attention to these duties.

From the mosque of the howlers a short distance takes us to another, where there is a well, which, the Egyptians are firmly convinced, communicates direct with Mecca. It is affirmed, in proof thereof, that a lady once dropped a water-jar into this well, and shortly afterwards going to Mecca, found it there. Turning to Christian traditions, there is the Coptic church, built over the place where the Virgin Mary rested herself on her flight from Jerusalem. There were three small niches in the sides of the cave, which the holy family were supposed to have occupied. There was nothing else interesting in the church, though outside, the small narrow, crooked streets, the high houses, the dirty inhabitants, the donkeys and small shops made each nook and corner look extremely picturesque, while at the same time the smells emanating from these same corners rapidly sent us off to more open parts of the city.

As in old days, the flies are the great plague. Nothing strikes strangers so much as the extraordinary manner in which natives, old and young, allow these flies to crawl about their eyes, nose, and mouth, without attempting to brush them off, or even seeming to feel them. We have often seen men lying down asleep in the middle of the day, with their nostrils and month quite covered with flies, and yet their sleep was as peaceful and calm as if they were dreaming the houris were fanning them. Naturally ophthalmia is very prevalent. It is very rare indeed that one meets an Egyptian who has both eyes perfect.

All people who come to Cairo should read the Arabian Nights carefully, not so much for the stories as for the excellent description of the everyday manners and customs which are now, at this moment, seen in all their entirety quite as much as in the days when that book was written. In any one of the crooked streets of the old town one sees the porter of Dinezarde, the three calendars of the story, all of them one-eyed, as if to carry out the exact resemblance; in some one of the corners sits the man with his basket of crockery and glass, probably dreaming on the very same subject as his prototype; the small coffee-shops, the talkative barbers – everything, indeed, is still present. But seeing the actual reality takes away much of the pleasantness, however much it adds to the graphicness, for it would require all the glamour of the most distant romance to enable one to think that any of these muffled-up harridans could be the beauties described in that book, or that the dirty, stinking, shut-up houses could contain the halls of delight that were ever present to our youthful fancies. Thus musing, we passed through the streets into the Grand Mosque at the citadel. The barracks all about here have had British troops in them since the occupation, and an amusing sight it is to see these soldiers, many of them bestriding the small and well-known donkeys of the country, and thoroughly enjoying their ride. The donkey-boys are famed for giving extraordinary names to their donkeys. They have Bismarck, Gladstone, Cornwallis West, Dickey Temple, and so on, and in some curious way they hit on characteristics of the person whose name they take. For instance, one of them, who owned the donkey Dickey Temple, proclaimed its goodness by shouting out, "Here, take Dickey Temple! He always goes; he never stop work, work; he always go!"

The mosque in the citadel is rather disappointing. It consists of one vast dome, with a large open courtyard towards the east. A certain amount of alabaster is used to line the interior, but it is not carved or decorated in any way. The really only interesting part is the tomb of Mahomed Aly, which is at the south-east corner, it being built on the place where the janissaries were murdered. It was a foul murder because it was done in so treacherous a manner, but there is no doubt that these janissaries, or small landowners of the country, were its tyrants, and that until their death no reform was possible; and however cruel Mahomed Aly was, one cannot help thinking that a little of this energy would have saved Egypt many sufferings in the last few years. On going into the mosque, they made us put on very large red cloth slippers, which caused us to slip about in the most absurd manner, and I could but laugh to think what grotesque figures we must have looked in them. Still, they do allow Christians to enter, thus showing a very different state of things from what it was even at the beginning of this century, when Christians were rigorously excluded, except, as in the mosque at Tunis, where a Christian workman was allowed to enter on all-fours, to repair the clock, "because," as the Sheikh said to his co-religionists who objected, "in case of repairs, is it not true, O true believers, that a donkey enters this holy place carrying stones on his back; and is it not also true that one who does not believe in the true religion is an ass and the son of an ass? Therefore, O brothers, let this man go in as a donkey." From the height here there is a splendid view of Cairo and the surrounding country. It is bounded behind by the Mokattem heights, which rise about two hundred feet above Cairo; to the left stretches away the little railway of Helouan, where are the sulphur baths; then from there, looking onwards and to the right, comes the Nile, with its multitude of boats, whose sails prettily reflect the rays of the setting sun. Far away are the Pyramids of Sakkara; nearer to us loom the great Pyramids, holding steadfastly to their right of being the principal objects of any landscape which contains them. Then come the palaces of Gazeerah; and next in order Cairo itself, with its teeming population; while, stretching out to the southward as far as eye can reach, again shimmers the Nile, flowing calmly through an ever-widening tract of magnificent cultivation. It is a curious circumstance with reference to old Cairo that, during the last cholera epidemic, there were very few deaths indeed in it, although it is in the most unsanitary state possible. Boulak, the quarter on the Nile, was the one that suffered most, as many as four hundred dying daily during the height of the disease. Attempts were therefore made to burn down infected closely inhabited parts; this was also done to the villages about, which were all hotbeds of the disease. They tell me it is perfectly wonderful how difficult it is to burn down closed-in earth-walled huts, particularly when, as my husband explained to me, they are built in rooms communicating from one to the other by small doors throughout their whole length, and, except these same doors, have no other opening; so the stench, he says, was frightful. All who saw them agreed that the air of Egypt must have a most wonderful health-giving property to enable people who inhabit such holes to live at all.

The great museum of antiquities is at Boulak, pleasantly situated on the banks of the river. The great object of interest to us was the late discovery of the mummies of the twenty-second dynasty. This is the one which contains the Pharaoh that Bible records say was drowned in the Red Sea. Should his particular mummy not be found, it will be an extraordinary and welcome affirmation of the historical correctness of that great Book. The belief which the Egyptians had in the absolute necessity of embalming was owing to their idea that in eternity the body could not come to life again unless all the principal parts were carefully bound up and preserved. Under these circumstances, something very peculiar must have happened to prevent the mummy of one of those powerful kings being laid with those of his dynasty. By-the-by, while talking of that period, I saw this morning a man dressed in one of those many-coloured coats which so strongly reminds one of Jacob's curious taste in dressing up Joseph in the same way.

While writing this, I was attracted by dogs furiously barking – evidently a tribal dispute, for from my bedroom window I can just see the boundary of the domain between two tribes of dogs. A small bridge separates them, and a most dreadful growling ensues when one or the other tries to pass the limits. I had hardly believed the many stories that have been told of the way different dogs have to stick to their owners but here I daily see the truth of those reports, and can vouch for their not being exaggerated. Quantities of pigeons, too, fly about. Every village has its pigeon-houses, looking like great mud cones, and in the evening the owners go out and call them in. An amusing instance of the usual Egyptian dishonesty was told me the other day. When a man wants to get hold of extra pigeons, he goes out of an evening, but instead of calling them he frightens the pigeons away. They do not understand this, keep circling above, and swoop down now and then towards their houses. Other pigeons, seeing this commotion, join them, and as soon as the man sees there are enough, he hides. The whole of the birds, old and new, then go into the house, and the man, returning, shuts them in. This would be a fine business if it were not that all of them do the same thing, and therefore each gets caught in his turn. They know this perfectly well, but no Egyptian fellah could resist the temptation of cheating his neighbour.

My husband has had a great deal to do to-day (the 2nd), as the Turkish reserve gendarmes declared their intention of not going to the war. The cause of this, in all probability, is some intrigue on the part of their Egyptian officers, who have the strongest objection to anything in the shape of fighting. It took every one by surprise, as they only made known their determination at the very moment they were called on to parade before the Khedive at the Abdin Palace. The Cairo Battalion of Egyptian Gendarmerie were also to appear before the Khedive at the same time. In the end, about one-third of the Turks thought better of it; but all those who had families and were domiciled in the country absolutely refused to go. The parade was held at 5 p.m., in the Abdin square, the troops marching past the Khedive, who was standing on the balcony of the Palace; General Baker, Sir E. Wood, Cherif Pasha, the Prime Minister, and several of the foreign consuls were with him. After the march was over, the troops formed up in close column facing the Khedive, who sent out a kind message to them by his aide-de-camp. Every one was much pleased with the appearance of the men, who were individually big, strong, and powerful, hardly any under five feet nine; and, having been almost without exception non-commissioned officers in the late Egyptian army, they were very well up in their drill. Their number was about eight hundred. The only question was, would they fight? Many of those who knew best expressed great doubts on the subject, and most others agreed with them when it was found 280 out of the 800 had escaped from the train while the regiment was on its way to Suez.

No other nation could show such a scene as that which took place at the Cairo station while the men were waiting to start, for between two and three thousand of their relations crowded the whole station, the women and children crying, screaming, and howling, begging their husbands, brothers, etc., not to leave them, not to go to certain death, etc., the soldiers responding, and nearly all crying, like the women themselves. Nothing, indeed, could possibly be more calculated to take every bit of soldier-spirit out of them, even if they had any originally; which I doubt, for the men were not in the least ashamed to cry, nor were they or their officers disinclined to say how odious the present duty was to them, and that, in going into the gendarmerie, they had expected to give up all active service and remain quietly at home. We were not at all astonished to hear of the number of desertions after seeing all this, and that, to prevent such an occurrence in future, martial law is to be declared in force for all troops going to the Soudan from the moment they are under orders.

Our departure for Suakim, which has been put off from day to day, is now definitely fixed for Saturday, the 3rd of December. So we have to repack a few things, leaving the others, with the house, in charge of an excellent Italian servant we have, named Anna Debenac. Before leaving, my husband went with General Baker to say good-bye to the Khedive, who received him most kindly, and told him that he was going to give him the rank of Pasha, and that he thanked him very much for undertaking to help General Baker in so onerous a task.

We, my step-daughter and myself, went to see the vice-queen, who lives in the Palace of Ismailia. The entrance to her apartment is the one on the left of that going into the Khedive's. As usual in all Mussulman buildings, there are no openings from or to the outside except those absolutely necessary, and however nice the inside may be, nothing of it can be seen by outsiders. The vice-queen's residence is no exception to this rule, for the Khedive is, above all things, a most strict Mussulman. From the outer entrance the carriage goes on about fifty yards, and then turns to the right through an archway, into first an outer and then an inner courtyard. In both these eunuchs are posted at every door. My husband left me when the carriage entered the archway mentioned above. We entered the harem by a double flight of splendid steps meeting in the centre, about fifteen feet above the level of the ground, and then on through a fine hall into the reception-room, to which we were conducted by some white women servants, who were all dressed very plainly, but in bright colours, green and red predominating. The vice-queen herself was seated on a sofa towards the far end of the room, ready to receive her guests. She is very stout, but at the same time very pretty; has fair hair and skin, with dark eyes and eyebrows. Her hands are particularly small and white, and she looks very aristocratic. She wears on her fingers some very handsome rings. Her hair is arranged according to the present fashion on the top of the head, with a few curls on her forehead. She was dressed in a very striking purple velvet brocade with long train, the whole trimmed with exquisite lace. Her manner was most engaging, quiet, ladylike, and pleasant. When we came in, she rose, shook hands, and asked us to sit down on a sofa near her. She speaks Arabic, Turkish, and French, and is very fond of seeing foreign ladies if they can talk French with her. She began to talk about matters in general, concerning which she seemed to be well informed.

In the meanwhile coffee was brought in, in small china cups without handles, and handed round by a woman attendant. These cups are inserted in filagree gold holders shaped somewhat like hour-glasses. The coffee Is made à la Turque – that is to say, with all the grounds in it; but, as these latter are very finely ground, they sink to the bottom of the cup, and the clear liquid remains at the top. The-vice-queen has four children, two boys and two girls. The girls I did not see, but the boys we often met when driving out. They look bright and intelligent enough, and it is to be hoped that they will get a European education. Their mother seems very fond of them, and she told me about her girls, how that once she had insisted upon the elder girl bathing in the sea, and that the poor child was so frightened that she nearly fainted on coming out. The vice-queen spoke most feelingly about it, and showed all through how fond she was of them, and how she looked after them. Whilst telling us this a very tall, very black eunuch came in and said a few words in Arabic to her. She answered; then, turning round to me, said, "Madame, votre mari est en bas, parce-qu'il m' envoie ses compliments."

This eunuch was decorated with the Egyptian medal, and looked taller than ever on account of being dressed in a long frock coat. There was nothing particular in the room we were sitting in, which was furnished in crimson and gold, with the walls panelled in gold. The carpet was a Turkish one, and the size of the room prevented the gold from being too staring. While coffee was being served the Comtesse de la Sala came in. She is a Russian by birth, and, like her country-people, speaks several languages very well, amongst them English. She is one of the nicest people in Cairo. I do not know much of the Comte de la Sala, who is A.D.C. to the Khedive, but my husband says the same thing of him. The theme of conversation happened to turn on the cholera, and the vice-queen said how sorry she felt for the poor people who suffered. She seemed to take it as a matter of course that she should have accompanied her husband when he pluckily came up from Alexandria to Cairo, at the time the latter place was at its height of its suffering. She gave one the impression of a kind, gentle, but spirited woman, whose great misfortune was being shut up in a harem, and thus unable to take her part in the outer world. On taking our leave the vice-queen again shook hands with us, and we got into the carriage and drove out of the courtyard, where we met my husband, who was waiting in an anteroom beyond.

The battalion from Alexandria has just come in. They are to go with us. It is as equally fine a regiment as the Cairo one, and the commandant is Colonel Iskander Bey, an officer who served under General Baker in Turkey.

As we had packed up everything, ready to start, and as my husband was too much engaged to go backwards and forwards from the house at Shoobra to his office, we all met for our meals at the restaurant of the Eshekiah gardens. From what we hear, there is very little to be got at Suakim, so we took care to enjoy the snipe, vegetables, and other good things that Egypt produces at this time of the year. One of the Egyptian officers told me that the other day the Minister of War, Ali Pasha Mobarek, gave a grand déjeuner here to all the officers going, at which several of the Egyptians got very lively. One or two speeches were made, a great amount of intention was expressed, and then all broke up, in order that they might seriously begin the work of the expedition.

On the 3rd, in the morning, we sent down all our luggage to the station, the troop-train starting at 7 p.m. We had with difficulty got hold of what appeared to be two good servants, one named William, a Levantine Englishman, who spoke several languages; the other an Egyptian cook. These were ordered to stay with the baggage and await our arrival. General Baker and several officers and friends were going to see us off, and so we went quietly down at six o'clock, thinking to be in time, when to our astonishment we heard a whistle, and saw the train moving along, amidst a prolonged howl from thousands of natives, assembled as before to see the men off. It then turned out that General Baker, wishing to put an abrupt end to this disagreeable scene, which could not otherwise than dishearten the soldiers, sent off the train suddenly. It was a very good plan as far as the soldiers were concerned, but, unfortunately for us, our paragon William had begun a series of thinking by ensconcing himself in a waggon with all our baggage, without troubling in the least as to our being present or not, and saying afterwards that he thought we were coming all right. So there was nothing for it but to go to Shepheard's Hotel and stay there the night. General Baker told my husband that in any case he wished him not to leave by that train, as he had some last orders to give him.

That evening there was a grand assemblage on the hotel piazza, amongst them, several Egyptian army officers, English, who naturally were all wishing to go to the war, and could not understand why the gendarmerie went, while the army were carefully kept back. A joke was passed round that it was "Wood's" army and therefore "wouldn't" go! I expect, though, that if Sir E. Wood had really his wish, he and his army would be in Suakim now.

By-the-by, I heard another bon mot of poor Colonel Morice Bey, the one who was afterwards killed, when Sir E. Malet left, and the first news came that Sir E. Baring was coming. He said with reference to both Sir Evelyn Wood and Sir Evelyn Baring, "Poor Egypt! there is one great evil in Egypt now; what will she do with another bigger evil still?" In the morning my husband went to General Baker's, and saw there Colonel Messadeglia Bey, an officer who had served under General Gordon in the Soudan, and had compiled most of the list of Arab tribes and their Sheikhs, which is alluded to in Colonel Stewart's most excellent report.

As a last thing before leaving, my husband drove over to the Ministry of the Interior to say good-bye to Mr. Clifford Lloyd, who was most civil and pleasant, wishing him all luck, and saying that he would much have liked to have gone himself, although he thought that few of the English officers would ever come back again. On arriving at the station, we found it crowded by officers and friends, waiting to see us off. General Baker was also there, and said he hoped to join us at Suakim in about ten days, but that he would not leave Cairo till he had seen everything go before, or in such a state of preparation that there could be no doubt of its reaching its destination. His parting instructions to my husband were – "On no account to advance until he himself arrived," but that everything that could be done by means of money should be tried, as soon as ever he landed. Also the troops were to be under his command; no orders were to be taken from the Egyptian authorities out there. At 11 a.m., the 4th of December, the train moved off, amidst general good wishes from all present. Four English non-commissioned officers who had been promoted to lieutenants in the Egyptian army came in the same train with us. They were to be used as scouts – a most important duty, and one which requires a large amount of pluck and coolness to carry out properly, for not only have they to point out the position of the enemy, but they ought to be able to make a very good guess of the numbers that they have seen.

Almost the whole route has already been described. The extra short distance from Nefish to Suez, being merely a run through the desert, requires no comment except as regards the beautiful blue waters of the Bitter Lakes, whose splendid colouring is brought out by the rich yellow of the surrounding desert. They say that these lakes teem with fish, but I saw no boats on either of them. We arrived at Suez about an hour after dark, and then were taken on by a special engine to the docks, where we found the Zagazig all in readiness to start. Our luggage and servant were there all right. William had only the most stupid excuses to make, and began soon to show that he, like all the rest of his tribe, required some one to wait on him, instead of his waiting on us. The cabins allotted to us on the steamer were very good, but although the night was dark, the frightful stinks everywhere proclaimed it an Egyptian steamer, manned by an Egyptian crew, with the unpleasant addition of a crowd of native soldiery. It was found, of course, that there was not sufficient food on board for the first-class passengers, and at the last moment we had to wait two hours before a fair start could be made. During that time careful guards were put on by Colonel Iskander Bey, to prevent any desertion. The men were informed of their being under martial law, but in spite of all that one managed to disappear, and it took some time before he was caught again. He was not tried by court-martial, because he might possibly have fallen asleep at the place where he was found, and though circumstances were very suspicious against him, yet possibly his excuse might have been true, for he looked such a fool. At 11 p.m. we started, so good-bye to Egypt for a time.

CHAPTER III.

THE MAHDI AND GENERAL HICKS PASHA.

THE MAHDI'S EARLY TRAINING – HIS PIETY – HE CLAIMS POWER AS A GREAT SHEIKH – STATE OF THE SOUDAN – HIS FIRST VICTORIES – HICKS PASHA – HIS DIFFICULTIES – INTENDED SOUDAN COMMITTEE – EXPEDITION TO GEBEL-AIN – STEAMERS LAID UP FOR WANT OF FUEL – EGYPTIAN TROOPS OBJECT TO OUTPOSTS – EXTRACT FROM HICKS'S DESPATCH ABOUT HIS SKIRMISH AT MARABIA – COL. FARQUHAR'S CORRESPONDENCE – REPORT RESPECTING YUSEF PASHA'S MARCH FROM FASHODA – DESTRUCTION OF HIS FORCE FOR WANT OF GUARDS – MR. O'DONOVAN – MR. POWER – DIFFICULTIES ABOUT WATER – DISGRACEFUL REINFORCEMENTS.

TO explain properly how the Suakim expedition came about, it will be necessary to go back to the events in Egypt during the last twelve months. The landing of the British army, the battle of Tel-el-Kebir, the masterly political and strategical movements of Lord Wolseley, are known to all in England. But it is not so well known that the troubles in the Soudan, Kordofan, and the equatorial provinces, had commenced about that time. Had Arabi been really a patriot, the small rising that it was then could have been suppressed at once; for the Mahdi, or Saviour, was then but a very unimportant man, with a very small following. As Colonel Stewart in his excellent reports relates, a detachment commanded by two Egyptian officers could easily have made him a prisoner if these two wretched Egyptians had not quarrelled at the last moment, and allowed themselves to be surprised.

The Mahdi, whose name is Achmet, was born in the province of Dongola; his father was a carpenter by trade. When Achmet was about twelve years old he began to disapprove of work, and went up to Khartoum to join his uncle. While there he made another bolt, and attached himself to the following of a Sheikh. These Sheikhs are a peculiar institution in the Soudan; they are supposed to be men under the special protection of a particular angel of God, whose interposition is effected by the Sheikh having isolated himself for eight or nine hours daily during a term of years, and constantly repeating all that time one of the ninety-nine names of God. After a period, as described when writing about the howling dervishes, the individual in question declares himself invested with the power of the angel, and it is supposed that he has received some occult intimation to the effect that God has ordered this angel to be his faithful slave, and to obey all his wishes, The devotee then takes the name and dignity of Sheikh, collects a following of dervishes round him, and proceeds to live upon the offerings of other people. It was in this way that Achmet went on.

After staying some time with his Sheikh, and learning by heart a considerable part of the Koran, he started by himself to the island of Abba in the White Nile. Here he stayed several years in a cave for many hours a day; he muttered or yelled the name of Allah (God); he fasted often and long, dressed in the most scanty and dirty clothes, and in every way fulfilled the Mussulman idea of a great religious fanatic. At last he emerged from this retreat, and commenced to claim power as a great Sheikh; and then, seeing his following increase very rapidly, he gradually began to claim power as the Mahdi. The times also helped him very much, for Egypt was just then in the throes of Arabi's rebellion. The Soudan was left to itself, and consequently more than ever misgoverned by the Egyptian authorities who were there. The Turkish Bashi-Bazouks, who, before the time of Gordon, kept the country quiet by wholesale bullying and tyranny, had been abolished by that general. No force was, however, left to make up for them. The Egyptian troops were willing enough to do the tyranny and bullying part, but fighting was quite another thing; consequently the Mahdi, obtaining some small successes at the beginning, rapidly increased his party, particularly when he declared against the Egyptian Government and against the payment of taxes.

There was also another thing that militated against the constituted authorities, namely, the abolition of the slave trade, and the taxing of the lands, villages, etc., held by the Sheikhs or other religious communities. The taxes used before to be paid in kind; money was not an available article. The Egyptian Government tried to change this, and insisted on money; and thus it became the custom, when a certain country was assessed, that the inhabitants should collect and hand over a number of slaves to some one of the great slave-traders who passed that way. From them they got bills on Khartoum, and so the taxes were paid with no other trouble than what they had been accustomed to from time immemorial, viz. a yearly slave-hunting expedition.

Just about the time that this means of payment became no longer possible, owing to the pressure put on Egypt to abolish slave-trading, and her loyal efforts to fulfil her obligations, the taxes were greatly increased on account of the religious properties becoming very much more extensive, and, according to custom, being exempted from taxation; thus, while the Government demand remained constant, the area of land taxed diminished so rapidly that even the fanatical Egyptian authorities began to think that religious lands could be let off their burden no longer. Every one then became discontented, everybody's personal interest was touched in its tenderest point, religious questions came into play, and just at this moment Achmet's pretensions to being the Mahdi were put forward. No event could have been more opportune for him, especially as all the traditions of the Mussulman world point out that year as the year of the true Mahdi's coming. He defeated the various few small expeditions that were sent against him without any difficulty. The Egyptian soldiers, there is no doubt, began to believe in him; they attributed magical powers to him, and declared that whenever they fired against him or his troops the powder changed to water and the bullet dropped close by.

During Arabi's rebellion, and the English occupation, no attention was paid to the Soudan, and the Mahdi was enabled, in the end of 1882, to gather a large force together in Kordofan, invest Bala and Obeid, and at last take both those towns with hardly any loss to himself, although garrisoned by a very strong Egyptian force. In these places were considerable stores of ammunition, rifles, and guns; it is not, therefore, astonishing that the prestige of the Mahdi increased to such an extent that his every word was considered sacred. How could it be otherwise, when all his followers were not even armed with spears and swords, but many had only sticks, and yet found themselves without loss in possession of all these, to them, wonderful things. The Mahdi further kept up his reputation by living as simply as ever, dressing as badly, and praying as much. He was also sharp enough politically, as he spared and treated well all those that gave themselves up to him and acknowledged his divine mission.

These latter events, the taking of Obeid and Bala, happened last year, just at the time when the Khedive had determined to try and stem the Mahdi's progress by sending up a few English officers to remodel his forces in the Soudan. First amongst them was Colonel Hicks, late A.A.G., Bombay Army. He had not much experience in active service, but had possessed the reputation of being an all-round excellent officer. The officers who were selected to accompany him were all from the retired list, it having been determined by the English Government, for some reason, that none of the active list should go. One would have thought that in a time like this the little help that was given would have been given in as ungrudging a manner as possible, and that Egypt would have had the choice of the whole range of officers on any and every list, and thus been able to get the best possible. As it was, General Hicks, for he was made a Pasha, got a certain amount of guns and cavalry, was appointed chief of the staff in the Soudan, and started off with special orders that the Delta of Senaar, between the two Niles, should be the first part of the country brought into order. General Baker and Sir Samuel, his brother, who had been specially consulted by the Khedive in this matter, both urged General Hicks not to attempt moving beyond the Nile, because, while there with the river steamers in his possession, his power for attack or defence was very great, but any movement away from those rivers enormously decreased his strength, owing to the great difficulties he would have to encounter from want of water in the arid districts.

General Hicks had, however, the greatest troubles to contend with. The English Government kept telling him that they were in no way responsible for anything he might do or any risk he might run; at the same time, they interfered so much with all the arrangements that he could not but think that he was under their control. He trusted, when he left, that General Baker would have the entire management as far as the Egyptian Government were concerned. I believe that the latter intended that this should be the case; and there is no doubt that a Soudan committee was at one time contemplated, the principal member of which was to have been General Baker. Unfortunately, this most sensible idea was not carried out, and so poor Hicks rushed unrestrainedly on to his fate. It will hardly be believed that even direct correspondence in an official manner between General Hicks and Baker Pasha was objected to. When General Hicks went up to Khartoum, he found his position of chief of the staff quite untenable, for, though all would listen, none would take his advice. It was only by threats of resignation that he at last obtained the necessary power. This he made use of by organizing an expedition down the Blue Nile to Gebel-Ain, the double mountain, where he met and defeated one of the principal of the rebel chiefs. Even on this short expedition, which lasted only a month, he was twice delayed for provisions, and yet the Nile was navigable along its whole length for steamers, and the wind at this time of the year blows permanently from a northerly direction. Several times the steamers were laid up at different points, waiting for fuel, although in almost every case the day before they had run out of wood they had passed some depôt or a forest where the fuel was usually procured from. Even as it was, in the small skirmishes which occurred in this expedition, he complained of the way the Egyptian soldiers fired in the air; how absolutely callous they were as regards sentries and outposts, the highest officers objecting, as they said the poor men would thus be placed in dangerous positions! A few extracts from General Hicks's letters and his chief of the staff, Colonel Farquhar's, correspondence, will give a good idea of the troubles they had to contend with. The first of them, dated the 6th of May, reports his action at Marabia, and is as follows: –

"Cairo, May 6.

"To his Excellency the Minister of War,

"EXCELLENCY,

"You will have received, through the telegrams from me, which I requested might be communicated to you, and from those of his Excellency Aladdin Pasha, Governor-General of the Soudan, the intelligence of our victory over the rebels near Marabia. On account of the great difficulty in obtaining any information, I preceded the main body of the army on its leaving Kawa, and with a small force proceeded up the river to reconnoitre and to take possession of the ford at Abuzed. On arrival at the ford, I found it in possession of a small body of Arabs, which I had no difficulty in dislodging. On the 23rd of April I remained there, placing the boats which I had brought up with me, containing Bashi-Bazouks under command of Yahia Bey, who is an excellent officer, in echelon across the stream, in which position they could command a very considerable length of the ford, which extends for about a mile, and support one another in case of an attempt at a forced passage. Having made these dispositions, I left on the morning of the 24th for a reconnaissance up to Gebel-Ain. On reaching the ambatch woods to the south of the ford, I discovered a large number of stacks of ambatch ready cut and prepared for raft-making on an extensive scale. A party was landed, and the whole of them were burned. These stacks had evidently been prepared by the rebels for use in the event of their being obliged to cross. On proceeding up the river, we found the banks occupied by straggling groups of Arabs, with whom we exchanged shots. On the 24th I visited the Shillock village of Mozran, having already arranged with the Sheikh for information to be obtained of the enemies' movements. I learned here that the rebels had left Gebel-Ain, and were marching in force under Ameer Makushfi and many dervishes to attack the 'Turks' on their march from Kawa, Having ascertained that the information was correct, I steamed back to the ford of Abuzed, warned Tahir Bey, and during the night I dropped down the river to join the army. I found the army at the north end of the island of Abba, and, with Colonel Farquhar and Captain Evans, joined it. In the evening the rebel cavalry appeared, and were driven back with a few shells. On the 27th of April we received information from a spy whom we captured, and also from other sources, that the enemy intended to attack us on that day; so, as we were in a good open position, and in front the country was wooded and unfavourable, I determined to remain and await the attack. But the night passed, and, with the exception of a few false alarms, nothing occurred. We advanced on the 28th, and on the 29th, before we had reached the unfavourable ground, Colonel Farquhar, whom I had sent with a few native Bashi-Bazouks to reconnoitre, returned with the information that the enemy were about two miles in our front, and were advancing at a rapid rate. In about a quarter of an hour after they appeared in considerable force, cavalry and infantry, and spread out round our flanks with the view of surrounding the square. They then advanced steadily and quickly, led, we could see, by several chiefs on horseback, with banners borne before them. There was some delay and difficulty in getting our guns into action, but at last this was effected, and the range being accurately estimated, at once the very first shell burst in the centre of some cavalry, a second was also effective, and this seems to have caused them, the cavalry, to move rapidly off to our right flank, and eventually off the field, for they appeared no longer as a compact body. The infantry still came on boldly, and, although shot down in numbers, succeeded in getting close enough to the square to throw their spears into it. There were not many armed with rifles, but two of our men were killed by

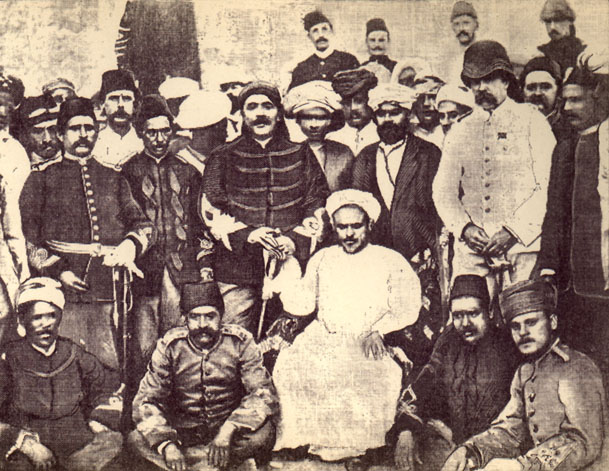

| Lt.-Col. COLBORNE. | Captain MASSEY. | Major MARTIN. | COETLOGAN PASHA. | Mr. EVAN. |

| Lt.-Col. FARQUHAR. | H. E. Lt.-Col. BAKER PASHA. | H. E. HICKS PASHA. | Captain WALKER. |

rifle-shots. I fancy the enemy fired high, as I am afraid our own troops did to a considerable extent. The action lasted for about half an hour, and the troops of his Highness behaved well and steadily. I estimated the strength of the enemy attacking us at the time to be between four and five thousand; but I have reason now to believe that I much underrated it. The enemy's loss in killed was about five hundred, with the Makushfi and six other chiefs; the wounded many. Our loss was trivial, viz. two killed and five wounded. Had I only had some cavalry I could have inflicted severe loss, as the enemy was completely broken up and fled in confusion."

In Colonel Farquhar's correspondence he mentions, on July 16, that the rebel forces about Senaar were dispersed, but it is evident that the Mahdi was in full power, for most of these Arab chiefs were with him. He says, since Lord Dufferin's departure from Egypt it is believed here that Hicks Pasha has lost his support at head-quarters, and therefore every obstruction is placed in his way. Slaten Bey had gathered together a certain number of men and defeated the Hami Arabs, who were not strong enough to attack the Mahdi al-Abeid. He also gives a copy of the report respecting the march of Yusef Pasha from Fashoda on the White Nile to Gebel Gedir.

It shows how utterly without precaution was the above Pasha's march.

The want of discipline is quite extraordinary; but the extract given below speaks for itself, and only makes one astounded that any Egyptian troops ever escape. Fancy the Pasha listening to his subordinate, Mahomed Suleiman Bey! It is really wonderful.