1

1

A Dream and A Blow

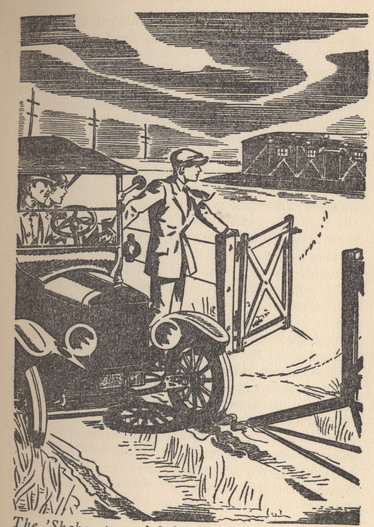

THE RATTLESHAKE, the Morgans' Model T Ford, chugged on and on through the white dust of endless, deserted roadway. Nobody talked; everyone was too tired. Charley's square hands steered automatically. Dad, small and spare of person, for once merely passive of mood, sat limply beside his son. As for Sayre, Charley's seventeen-year-old twin sister, so tightly was she wedged in among the camping equipment and supplies of that back seat that she could not have moved even if she had not been afraid of awaking Hitty, weightily asleep in her arms.

All day the 'Shake had been jolting them across Wyoming. Mile after mile of desolation. Great gray stretches of arid plain as far as eye could reach. No hint of people anywhere except an occasional glimpse of a sheepherder's wagon in the distance. No sign of animal life except a snake, probably a rattler, which Charley had pointed out to them sunning itself beside the road.

All day that hot, dry wind, laden with light desert dust, had swept into their faces, parching their skin and torturing their eyes, while overhead a fierce sun had glared down on them out of a sky too brilliantly blue.

Now in the late afternoon it was cooler. Because of the altitude, Dad said. They were coming into inhabited land, too, still flat and treeless, but spotted with large, green-cropped fields, cut with canals and ditches through which slow water flowed. Dad roused occasionally to point out some especially luxuriant stretch. "That," he would say in a triumphant tone, "is what this land will do when Uncle Sam brings water to it. Builds a big dam — maybe miles away — and a whole irrigation system.

Most of the buildings scattered among these fields were little more than low, flat-roofed shacks, relentlessly exposed to that hot sun and dry, beating wind; yet at the same time lost, too, in the wide monotony of the landscape. Only occasionally did a real house appear with gabled roof, and porches, and sheltering trees. Some of them, Sayre reflected, looked homey, and she wondered which kind Sam Parsons' house would prove to be when they got there. It was to be their home, their new home, here in the West, and — Sayre's hope was almost a prayer — their real, permanent home, at last. Her thoughts were busy with speculation as to the future that lay only a few miles ahead of them now. It held uncertainty, and risk, and plenty of hard work for all of them, she realized; discomfort, too, if the Parsons house were just one of these small, tarpapered shacks. Well, whatever the house, the fields themselves were beautiful. Great shimmering masses of tall green, tinged all over their tops with varying shades of purple from delicate, spray-like blooms. This must be alfalfa; Sam Parsons had told them that this was alfalfa country.

Suddenly they were running into a town. "Upham," Dad chirped. "Biggest town on the whole Pawaukee Irrigation Project. Nearly a thousand people.

Sayre scanned the place from over Hitty's tousled head. None of the mellow loveliness of those faraway, tree-shaded villages that she remembered as a child. A charm of its own though. Small, but very trim and confident under that lowering sun. Something almost blatant in the newness of its red brick business blocks and the wide bareness of its one main business street, lined with upstart sticks which were as yet scarcely even promises of trees. Sayre did not know these yet for cottonwoods.

Charley brought the 'Shake to a stop in front of a store before which stretched a wide platform of wooden planks. A tall, angular man was standing there talking assertively to a boy of about Charley's age. The boy was as tall as the man, but darker and much more heavily built.

Dad leaned out of the 'Shake's open side. "I'm looking for a tract of land," he said to the pair. "An unproved-up homestead claim known as Parsons' Eighty. It's seven or eight miles beyond this town, I believe. Do you know the place? Can you tell us, please, which turn to take?"

The man stepped toward them with genial, self-important bearing. "Gladly." He gave them directions with a courtesy almost exaggerated. "Strangers?" he finished.

"A friend of Sam Parsons. Came out here from Chicago to take over this abandoned homestead claim of his. Name's Morgan, sir, Charles Morgan."

"I am Franklin Hoskins. We'll meet again."

"That fellow sure thinks he's somebody," Charley commented as the 'Shake sputtered on.

Dad was excited. "Hoskins," he repeated. "That's the man Sam Parsons said was the community's most prominent citizen, the best and most generous friend the farmers on this part of the Pawaukee Irrigation Project have. Wasn't he pleasant?"

Sayre did not answer. She had noticed the way the man's glance had flitted over Dad's small person with a quick interest that had had something "funny" in it. "Almost as if he owned him," she thought, resentfully.

"It was the young fellow took my eye," Charley was remarking. "Sure built like a football player. Bet he's a good one."

"Looked too sulky to me," was Sayre's indifferent response.

The country through which they were now traveling was less attractive than that on the other side of the town, sprinkled less often with settlers' shacks and showing fewer cultivated fields. Dad and Charley were too absorbed studying Sam Parsons' directions to notice much, and soon they were turning in at a gateway through a wire fence. The 'Shake bumped and leaped over deep ruts in a sage-mottled strip of hard, gray soil, evidently a pretense at a driveway; and lurched at last to a stop behind a queer-looking black building, low, long and narrow.

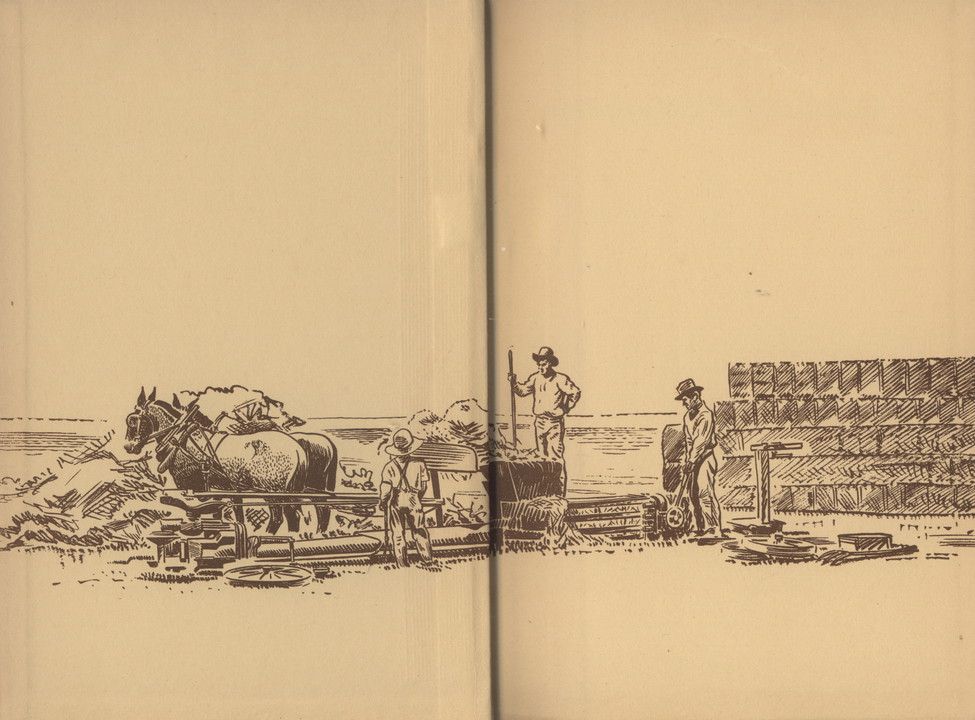

The 'Shake stopped behind a queer-looking black building

So this was the house. Yes, it was only a shack, built without foundation on the ground, and shaped like an enlarged and elongated freight car. Two doors exactly opposite each other marked the centers of both broad sides. Before each door ran a low step. Windows, fairly large but placed peculiarly high toward the roof, punctured all four black walls symmetrically. The roof, too, was shaped like that of a freight car. At Sayre's first glance this roof was the building's most conspicuous feature. For as a means of protection against the ripping of the winds, its tarpaper covering was studded thick with huge metal discs, which glistened now under the setting sun like enormous thumb-tacks.

"Here we are!" Dad proclaimed. He hopped from the 'Shake with that spryness like a bird's which always marked in him one of his moods of elation. Charley sprung out feet foremost over an unopened door. Hitty was waking up. Sayre sat still for a moment, looking about her.

Weariness dropped from her like a cloak. Her spirit began to glow and soar to new happiness and new hope. Not even the ugly, crude little house could spoil this place, she thought, under a spreading sunset glow that spread its evanescent tints over all this great world of soft silver distances and touched even that encircling, protecting horizon of haze-hung mountains. It was lovely, she told herself as she set about waking Hitty; and wasn't this shack a lot better than that dark, dingy flat on West Van Buren Street in Chicago which had been the latest of the Morgan family's many habitations? And when she remembered some of the others, and how many times they had moved —

Dad was lifting Hitty from her lap to the ground, and Sayre followed. The wind had gone down, and the air was clear now and wonderfully exhilarating. The girl drew a deep breath. It tingled through her like wine, with a peculiar tang in it, a spiciness which she just seemed to catch at the very moment it eluded her. Must be the sage.

Even Hitty felt it. Her hand fumbled into Sayre's, the little girl murmuring sleepily, "Oh, doesn't it breathe nice here?"

Stooping, Sayre swept the frail child to her with an impetuous hug. "Doesn't it, baby?" she exulted.

The embrace startled Hitty far enough awake to confide in a whisper, "What makes it so awful still? I can 'most hear my thinks tick." The child slipped away to break into a sharp, glad cry, "Oh, Sayre, see what a nice far look there is!"

Sayre did see. Then for a moment Charley almost spoiled things. He had been lifting baggage out of the 'Shake, but stopped now to nod at his twin with a wave toward the new shelter. "Guess we can pack the Morgans into the Crate!"

Sayre bristled. Just like Charley, dubbing the place right off with a joke. The house did look like a huge crate — she had to acknowledge that — the way those laths were crisscrossed over the outside to hold the tarpaper on. Laths evidently did on the outside walls the work the discs did on the roof. But what of it? Did he expect to be given a palace? She spun around toward her brother. "Who cares what it looks like? A crate or anything else? If it's a home crate?"

Snapping at Charley wasn't the right way to begin, she reflected, though unrepentantly. To see him show signs of that awful changeableness of his right off, just because the place looked dreary! It wasn't very attractive on the outside, she admitted to herself. The ground around the house was pretty bare; it had queer white patches on it as if it had been sprinkled thick with coarse salt. Alkali, Sayre had already learned. But well behind and to one side of the house reached out great massed stretches of those glorious, green, purple-flowered fields.

Thank goodness, Dad was still confident. He had unlocked the back door with the key Sam Parsons had given him, and was flinging it wide.

Sayre stepped into the opened doorway. Trembling a little, she lifted one arm to brace her hand against the door jamb and let her glance sweep in half-fearful appraisal over that interior. Larger than she had expected from the outside. Partly filled with untidy furniture, covered thick with dust. Dad was cautiously lifting one home-made window shade. Late sunlight fluttered in. It revealed long diagonal lines of shimmering dust motes across unoccupied space; a greasy cookstove; cobwebs, everywhere; old papers in corners, mouse-nibbled.

Dad kept on moving briskly about, opening the whole place up to air and fading daylight. Just three rooms. A bedroom partitioned off at each end from the one main big room, which after all was really two. One half of it was meant for living-room; that was plain. The other half was kitchen. When cleaned up, what a cosy kitchen it would be! Its compact arrangement of shelves and table and benches and stove made of it a sort of country kitchenette, much nicer than any city one, because into it sweet air could flow and sunshine flood. "It's like a great big country dollhouse," Sayre thought happily. She turned and called Hitty to come and see.

All her misgivings were gone now. With everything scrubbed up, and Dad's easy chair in it, and the books, and Mother's picture, and the curtains, freshly laundered, she no longer had any doubt of being able to make a home out of this place.

The Parsons family had left enough in the house for them to get along with temporarily until their own things should come, things Aunt Mehitable's money had paid to bring, just as it had paid to get the family there. As always, thinking of Aunt Mehitable's money made Sayre feel ashamed. She went back to the 'Shake and set to work helping Charley unload.

Sayre slept that night with a profundity born of the enfolding silence. She awakened, wonderfully refreshed, to stand at her bedroom window and watch the dawn. No one, not even the most favored of Chicago's millions, ever saw a sunrise like that. Instinctively the girl sank to her knees on the floor. Elbows propped on the sill, chin cupped in her hands, she watched the scene with reverence and bated breath.

Behind her on the bed, Hitty stirred in her sleep, fair hair spread wide on the pillow, one thin arm outflung. The sound brought to Sayre the swift crystallizing of a resolve so deeply felt that it became a vow.

"The Morgans are through with moving. We're going to stay here. We're going to make a home here. Hitty's little yet. She's going to have a home and live in it, and be one of a family that really belongs somewhere. And that somewhere's going to be right here on this federal irrigation project in Wyoming!"

All her life Sayre herself had longed for a real home — above all, a home in the country. She had never expected actually to have it. But she had liked to escape into the dream of it when realities were hard. When she drew books to read out of the public library, she always sought out farm stories, or else tales of the days before all this great western United States was settled. Then the Government had given away new land in the West to people who would live on it, improve it, and make farm homes out of it — what they called homestead it. Sayre had devoured eagerly every story about this sort of thing she could lay hands on, filled with regret that the time of these stories was always in the past. If only, she had often thought, there were such opportunities now!

Then this summer Sam Parsons had told the Morgans there still was new land in the West on which people could homestead. He had explained to them everything about it. It was land overgrown with sagebrush and dwarf cactus, which nobody had thought worth anything in the old days except for sheep grazing. But all it had really needed to make it produce was water. And now the Government had brought water upon it by means of its big dams and irrigation systems. Mr. Parsons had shown them maps and diagrams that told all about such systems. And, at last, thanks to Sam Parsons himself, who had really brought about their coming, here they actually were, the four Morgans, arrived on eighty acres of this new, reclaimed, irrigated land. Could anything so good be really true?

Gratitude surged through the girl's heart toward fussy Mr. Parsons. She felt very guilty these days that she had never used to like him. He was a floorwalker in Reeves & Beebe's department store basement in Chicago where Dad had clerked for a while in the hardware department.

Mr. Parsons and his wife had started to homestead these eighty acres two years ago but had never proved up on them; that is, lived on them and improved them enough to get full legal ownership of them. Mr. Parsons' wife had hated the loneliness of the life, and Sam himself had found he was never meant for a farmer. So they had come back to Chicago and turned over to Dad, on long, very easy terms, their chance on these eighty acres of homestead land, already partly cropped, and fenced, and provided with temporary house and sheds. Sayre was still lost in the wonder of it. Thankfulness sang in her this morning softly like a prayer.

Suddenly she shivered at her open window. The morning air was chill in this high altitude. She rose and began to dress. She was a sturdy, dark-haired cricket of a girl; every movement was quick and true. She had need to hurry. There was lots to do today. Was she not the Morgan housekeeper? She had been ever since her mother's death three years before.

It was afternoon before she went with Dad to town. He had to see about having the right to homestead these eighty acres transferred from Sam Parsons' name to his own — to "file on the claim," as the phrase was, for himself.

Sayre gave Dad's hand a quick squeeze as they entered the land office of the Pawaukee Irrigation Project. Dad did not seem to fit into the place. It was such a new, shiny room, and Dad, in spite of his cheerfulness, looked old and worn — just like that threadbare suit of his which would sag to shapelessness in spite of all that her iron could do.

The land agent was not the only person in the office. In a back corner three men occupied tilted chairs in a semicircle of friendly intercourse. Undertones from their conversation reached Sayre as she sat and listened to Dad telling the agent how the Morgans' move had come about. And now, hearing the story as it was told to a stranger, Sayre found sweeping over her a deeply dismaying realization of what they had really done. She hadn't thought about it in this way before. What had they actually known, back there in Chicago, about the situation here? Nothing but what Sam Parsons had told them. They hadn't asked, hadn't looked up facts, had just accepted his word for the conditions that they would find, and come out in blind confidence that everything would be all right. Why did Dad have to be making all that so clear to this man? He even told the agent that the money for the move had come from Aunt Mehitable, "the principal of a big New York City public school." Why tell that? What business was it of the land agent's? Dad was so simple and straightforward and honest that sometimes he was too frank.

"You can see, sir," he wound up, "what this venture means to me. I'm a man with a dependent family, sir, a widower. I've been unfortunate in the past. So a chance like this, to secure a comfortable home for my family and an assured future — it is nothing less than a godsend."

The land agent looked grave; he began to ask questions. Sayre shrank from her father's answers. Long before that questioning was over, she wanted to cry to the questioner, "Oh, please don't try to be so kind. Just tell him right out!" For there was that in the agent's manner, sympathetic though it was, which made Sayre feel humiliated. She wanted to rise up and shield her father. Instead she only sat very quiet, consternation mounting in her heart, her intent blue eyes watching the cheerfulness of her father's face fade into that gray dejection which, even as a little girl, she had learned to dread with an astuteness beyond her years. It so often followed a new move. Why? Why, anyway, all her life long, had their family had to move and move and move?

Aunt Mehitable said it was because Dad was visionary. Sayre had come of late years to understand what her aunt meant. Dad was always seeing somewhere at a distance ideal conditions of living which made what the family had unendurable. Yet when his restlessness had found a way to grasp at this distant vision, it was never what it had promised to be; often it was worse than what they had left behind. Then Dad would grow restless again, and begin to reach out toward another dream.

Dad exasperated Aunt Mehitable. Yet she really loved him, Sayre knew. The girl could remember hearing her aunt sigh and say that Dad had never been meant for the practical world, that if only his eyes had not failed so badly during his theological seminary course, life might have been very different for him and for his family.

As it was, the family had lived in so many places that it was hard for Sayre to remember their exact order. The Ohio town where Dad had had a shoe store. The Michigan mining town where Aunt Mehitable had bought Dad a little hardware business — which she had had to sell again because Dad would trust people he never should have trusted. New York City for quite a while after that, with Dad a partner in a second-hand bookstore which had failed, leaving Dad stranded again and hating New York's turmoil. The family had drifted south then, to towns in West Virginia and Florida, then back to a Pennsylvania coal town where Dad had sold insurance and real estate for a man, and the man had absconded.

There had followed that slow sort of gypsy trip back to the Middle West, with Dad selling a line of household mops and brushes to small-town merchants. In this capacity he had at last reached Chicago, having looked forward to it as a big center of opportunity, but finding himself unable to cope there with the competition he met. From then on he had been a grasping at any opportunity to earn some sort of living, Dad always calling what he was doing "temporary," and looking for something better. Clerking in Reeves & Beebe's basement had been the last.

Of all the places they had been Sayre shrank most in memory from the shabby southern Indiana town where, on their way Chicagoward, Mother had died suddenly of pneumonia.

Dad had been discouraged much more often since then. He blamed himself deeply, Sayre knew, for having made their mother's life too hard. Sayre's heart ached for him; yet she knew he was right to blame himself. He had made life too hard for all of them; it had not been good for them. Charley was growing up restless and fickle, and Hitty, frail.

Thus had been planted in Sayre, before she was old enough to be conscious of it, that longing for a permanent home which had grown deep-rooted with the years. Because of it, no member of the Morgan family had welcomed this Wyoming move more eagerly than she.

And now!

The agent kept talking on and on about a lot of complicated things: alkali; new soil conditions; drainage; settlers' failures to meet Government construction charges; losses of money; abandoned claims; new rulings; a Government investigation into the situation. Through all this Sayre's clear, candid mind slashed straight to the awful truth.

Dad could not file a homestead claim to the Parsons' eighty!

Worse than that, he could not file a homestead claim to new land anywhere!

Why? Unflinchingly Sayre's mind sifted away all but the hard kernels of the facts.

Dad could not file on Parsons' eighty because farming on some of the federal irrigation or reclamation projects, including this part of the Pawaukee, had proved so disastrous that the Government was not letting settlers file any more until it had studied out the causes of all the trouble. He could not file on new land anywhere because he had no money, no equipment, no supplies. He had never farmed before; he did not know how to farm. He had never, really, been a success at anything. The Government did not want — would not have — men like that as homesteaders. And Sam Parsons must have known all these things when he had let them come.

Sayre sat trying to grasp this, and found she couldn't. She felt stunned, all her joyous hopefulness of the morning submerged in terrible disappointment. Would that agent never stop talking?

"You're welcome, Mr. Morgan, under the circumstances to stay on the Parsons place as long as you find it convenient, but I can give you no legal hold nor prospect of possession. Not all the land out that way is a failure, either. A few farmers, mostly foreigners, are making things go. And that Parsons' eighty has twenty mighty good acres of alfalfa — if it's free."

Only much later was Sayre conscious of having noted that last phrase. Now it seemed there was not a feeling in her. Yet her pride was quick to detect that Dad was meeting the situation with his usual self-effacing dignity. Fiercely she loved him for it.

The two men rose, and Sayre realized that the agent had said something about their need to look in at another office down the street. Her father asked "May my daughter stay here while we are gone? It would be more comfortable for her than out in front in that burning sunshine." She hardly noticed the two going out, so numbed was she. Yet through her numbness there was already rising something stubborn and defiant. What was Dad up to now? Going out to see if he could pick up some kind of temporary job to tide things over? That was what he was always doing. Giving up. Yielding to discouragement. Why couldn't he ever fight harder against circumstances? Against situations like this? Why couldn't he for once be more like Aunt Mehitable? Aunt Mehitable never gave up. She always managed somehow to accomplish the thing she had set out to do.

Sayre leaned against the wall, and shut her eyes tight to squeeze back the threatening tears. Her body was rigid; her will-power centering in one vast determination.

It was Aunt Mehitable whom she, Sayre Morgan, was going to be like. Not for all the land agents in the country, not for all the rules the Government could make about homesteading new land, was she going to give up this beautiful dream of hers which had seemed so near accomplishment, a farm home for the Morgans which one day would be all their own!

Wild schemes raced through her head. If times were so hard on these farms around here as that agent made out, there must be some people who had lived on their land long enough to prove up on it — that is, get full legal ownership of it — who would be willing to sell out for a song. Well, what difference did that make? She almost laughed. Perhaps she was a bit hysterical. The Morgans had not even a song. All they had was a rattletrap Ford, some shabby furniture, a few worn-out clothes, and a ten-dollar bill. And that ten-dollar bill was Aunt Mehitable's.

Suddenly she sat erect, jacking up her thoughts in self-contempt. Here she was, letting her mind run on it the way Dad talked in one of his despondent moods, when she had just decided that she was going to be like Aunt Mehitable! Why, they had a good roof over their heads, a place they could stay on indefinitely even if they could not own it, the right to use the land. They had health and strength. Not by any means did she have to give up her dream. Part of it seemed gone. She would have to find a way to bring that back; she would do it, too. But even now for the present there was a part of that dream to which she could cling. They could all learn to farm. Perhaps Dad and Charley could get work on one of those nice places out the other side of Upham where they would learn a lot, and earn. Then, later on, the day would come.

She opened her hands. She had not realized she had been sitting with them clenched. Body and mind began to relax. Into her consciousness floated scraps of talk from the men at the back of the room. She caught the word "Hoskins." Why, that was the name of the man of whom they had asked directions yesterday. She listened a little.

Evidently this Mr. Hoskins was president of the local school-board. One of these men at the back of the room, too, the big man with the foreign speech, seemed to be on the board. There had been some kind of trouble. Mr. Hoskins had been trying to keep some high-school teacher from being rehired and the big foreigner had kept Mr. Hoskins from getting what he wanted. The teacher in question was a Mr. Kitchell, who was high-school athletic coach and who also — Sayre caught the words distinctly — taught agriculture.

Taught agriculture! Sayre clutched at the phrase. It was more than the proverbial straw to the drowning man; it was a floating spar. She began to listen with all her might.

"What's Hoskins got against Kitchell anyhow, Hansen? Is that big lump of a Frank Hoskins so swelled in the head about his football playing he can't get along with his teachers? Kitchell's always struck me as about as fine a young chap as we've ever had on our teaching force."

"Nuttin' personal. Nuttin' personal at all." Into the monotonous voice with the foreign accent crept a good-humored sarcasm that evoked ripples of amusement from its hearers. "Meester Kitchell is a most esteemable young man." (The words were plainly a quotation.) "But he can't coach so good as — "

"Oh, come on, Hansen. We all know Hoskins' blind talk as well as you do. What's he really got against the teacher?"

"Dat's easy. He hates de teacher for vat he teach about alfalfa, dat ve must not sell it so much, dat ve must plow it into de soil. Hoskins is, I t'ank, afraid a leetle. Ain't he de big hay-buyer of all dis part of de Pawaukee Irrigation Project?"

"De teacher says vy ve farmers is all so hard up is because all de time most of us raise alfalfa hay to sell. He says dat ve must plow under all our alfalfa ve do not need for our own use, and plant udder crops vere de alfalfa vas. Ve must get livestock and feed 'em our hay and our udder crops. Den ve vill not haf such hard times. De Ag teacher, he teach dis all de time to his boys, and Hoskins, he don't like it.

"De teacher says, too, his big yob ain't football. His big yob is to make real farmers out of dis part of de Pawaukee's farm boys. I t'ank, maybe — " and the monotonous voice broke into a sudden chuckle; then added with an expressionless distinctness startling in emphatic effect, "Hoskins ain't ready yet for too many good farmers on dis part of de Pawaukee Project!"

Silence, expressive of understanding, was broken by, "All the other board members vote with you, Hansen?"

"Ven Hoskins, de big man, kick so plenty? Not on your life! Ve have only von more vote dan half, and vat got him vas de teacher's idea for anudder agriculture course, vat he calls a part-time class."

"Ain't ve all poor like Yob's turkey around here? And our big boys, ain't ve got to have 'em home most all de time for vorkin' if ve're going to hang on to our land? And don't dat make us feel mighty bad, not to give our big boys no shance?

"Veil, de Ag teacher say after football he don't vant to be athletics coach no more. He vant to run a short Ag course for our big boys in de dull farm season, four months, November to a little in March, all day at de high school. In de mornings he vill teach 'em agriculture and farm shop; in de afternoons udder teachers vill teach 'em English so dey can speak and write good, and Civics to make 'em good citizens. Even Hoskins can't beat down dat good idea, so ve vote back dat teacher."

"Hoskins'll sure be loving you for that, Hansen."

"Vat vould I vant," again the monotonous voice broke into that irresistible chuckle, "vid Hoskins loving me?"

At this point, with Sayre leaning forward, her mind a sudden whirl of new ideas — in came Dad again. She knew at once that whatever his errand had been, it had not been successful. He came out of his dejection for just one flash of cheerfulness on their way home.

"Sayre, I met that Mr. Hoskins in town. Knew me at once. Was most cordial. I had not the heart to tell him the truth about our situation, even though Sam Parsons said he was always so helpful to everybody around here."

"Oh, Dad, surely you can't believe Mr. Parsons' ideas about people or things out here, any more?"

Her father sighed. "I can't bring myself to believe that Parsons sent us out here under intentionally false pretenses."

"That land agent certainly believes it! The queerest look came into his eyes, kind of sharp, it was, when you said Mr. Parsons thought he might come to visit us next summer."

"But what could Parsons' object have been if he knew the land was too worthless for me to want it? And that they wouldn't let me have it anyway? Sayre!" The sudden tightening in Mr. Morgan's tones implied one of those flashes of insight he sometimes had, always as an aftermath of disillusioning experience. "Parsons must want to hold on to that land! We're out here to work it for him the way the Government requires a homesteader to do. It requires him to live on it, too. That's what he'll tell the Government he's doing when he comes to visit us. To think that a man I had such faith in could be so underhanded!"

So Dad saw it at last, and she didn't know whether to be glad or sorry. But her mind was by now busying itself over something more important. This afternoon's experience had been valuable, in spite of the distress it had brought, for out of it there was slowly emerging a plan; she spelled it Plan in her mind, with a capital. As she turned it from side to side during their journey homeward, trying to see what it involved, and all that it might mean to the Morgans, she made up her mind that she would keep it a secret. No use of talking about it yet, not even to Charley; but tomorrow she must get at the first steps. The thought of Charley made her wonder what effect the news that she and Dad were taking home would have on him. Start him off again on some crazy notion, joining the Navy, like as not! Yet without Charley she could not hope to carry her Plan through, however persistent she herself might be. Hang on to her brother she must.

As they pulled up at the "crate" her father asked her what she was smiling about, but she only shook her head. Really, she was smiling a little ruefully at herself, remembering some of the things that Aunt Mehitable had so often said to her; that however changeable — sometimes even undependable — Charley might be, she could hardly sit in judgment on him as long as she kept her childhood impulsiveness, her impatience with other people that was often actual crossness, her insistence on having her own way, her "bossiness," Aunt Mehitable called it! All right, maybe she was bossy; somebody had to be, in the Morgan family!

2

2

Sayre's Plan Is Started

IF SAYRE could keep a secret, so also could Charley. For the result of the evening's dismayed discussion among the three of them was his announced decision to go straight to town next morning, on what errand he would not say. Sayre contented herself with asking to be driven in with him; if she showed herself inquisitive about his reason for going, he might insist on knowing hers. So, while he was parking the 'Shake, she slipped away to the Upham Consolidated School building.

"The Ag teacher's office is at the head of the stairs," the janitor told her when she sought him out to inquire. "Go right up and in. Mr. Kitchell's there; he stays on the job all summer."

Sayre's step slackened as she climbed. Not that she was backing out. Only, even enthusiasm and determination have moments of misgiving. She had expected to find this Mr. Kitchell alone. Those voices upstairs proved he had company.

She recognized one voice, little as she had heard it. It belonged to Mr. Hoskins, smooth and pleasant, yet "awfully cocky." That other voice was nicer, it must be the Ag teacher's.

Sayre mounted four more steps. She could hear every word. Yet those men weren't talking loud! That distinctness must come from their being so awfully polite to each other.

Alfalfa. Was it always alfalfa people were talking about on this Pawaukee Project? The voices rose higher.

Why, this was a scrap! Those polite words were really blows. Ought she to go right in? She'd wait a little first, standing just outside the open doorway so that they would know she was there.

The nice voice was speaking. "I have never discouraged alfalfa projects among my pupils, Mr. Hoskins. Alfalfa is essential to this country as a first crop, to be plowed under to give this light soil the humus it must have to grow other things. But I have used, and I shall continue to use, all my influence against this steady wholesale marketing of alfalfa hay for ready cash. Such a procedure is ruination to our farmers. Our present circumstances prove that."

"Our present circumstances," rejoined Mr. Hoskins a little sharply, "prove that our farmers have to sell for cash anything they can get cash for! Men in such straits can't live on your hazy 'future prospects,' Mr. Kitchell. We will dismiss the subject for the present, however, and get down to the matter that brought me here.

"I'm in the alfalfa business. I want my son Frank to learn that business, all of it, the growing side as well as the marketing. That is why he is enrolled in your regular four-year high school vocational agriculture course. Nowhere, I knew," the voice settled into a purr, "could he learn the growing part better than under your efficient instructorship."

The other man made no attempt to break the ensuing pause.

"Mr. Hoskins can't jolly that teacher," thought Sayre with delight. She was growing uncomfortable. Yet she was not eavesdropping; she was within plain sight of both those men.

"But Frank" — censure slid slyly into the smooth tones — "is not so much interested as he should be. So I propose to stimulate his interest by offering a prize for a contest. All your agriculture pupils will be eligible, Mr. Kitchell, those who will enroll in your part-time class as well as those in the regular high school course. It will cost no pupil anything to enter. I shall provide the seed."

Sayre stepped nearer, her personal interest pricked for the moment to the point of unselfconsciousness.

"I shall offer a prize of one hundred and fifty dollars to that pupil who by the end of the next growing season shall have received the highest market returns from five new acres of alfalfa, either of fall or of spring planting."

Sayre's eyes grew big. A contest open to both groups of high school Ag students. Could anything fit better into her plan? And one hundred and fifty dollars — a magnificent sum!

Then her attention centered again upon those men. The silence within that room was growing uncomfortably long.

"This is, of course, Mr. Hoskins" — my, but that teacher was chilly! — "an attempt on your part to destroy my influence among my pupils — to undermine my teaching."

"Not at all, Mr. Kitchell. Not at all." The teacher's increased aloofness was as nothing compared to the other man's increased pleasantness. "Not for a moment would I have you or anyone else put such an interpretation upon my offer. My sole object is to induce my boy to learn the complete alfalfa business."

Another silence, longer than the previous one. "I do not see how I can refuse your offer," came at last without any thawing in the teacher's tones. "I make one condition. It must be understood this prize contest of yours is a private affair, offered without my personal or professional sanction. Under that condition I shall do all I can to help the alfalfa growers." The emphasis on the last word was unmistakable. The teacher stood up. Was it because he wanted his visitor to leave? He was still talking. "But I shall advise against the selling. For unless this locality's farmers go in before long on a bigger scale for something besides market hay, they're done for. I cannot believe that a man of your intelligence fails to realize that fact as well as I."

Sayre's indecision was over. She was not going to hear any more; but she wasn't going away, either. She stepped forward and knocked, well aware that the hard, dry sounds her knuckles made were puncturing an atmosphere taut with tension and constraint.

Another intrusion was at hand, however, in the approach of a big lad who lumbered up the stairs to brush past Sayre into the office. It was the boy whom she had seen two days earlier talking with Mr. Hoskins, evidently "my son Frank" arriving by appointment to meet his father. He gave a surly nod toward Mr. Kitchell and stood by, indifferent to the point of ungraciousness, while the older man made a stiff farewell to the teacher. Then both were gone.

"So that's the Hoskins boy," Sayre thought. "Why didn't he say something? Not be so rude! He doesn't look like his father, but he's just as horrid."

Yet there had been something impressive about that boy. He was finely built, a little overgrown, but muscular, not fat; and his dark, brooding eyes had caught the girl's attention and held it.

Mr. Hoskins, meanwhile, had given Sayre just one glance. What was in it? Not resentment exactly; she was not important enough for that. Just the same she knew he had not liked her overhearing Mr. Kitchell "get the best of him." Sayre did not care. For no reason at all, she had drifted into the spirit of that overheard scrap entirely on Mr. Kitchell's side.

She moved expectantly forward to the chair Mr. Kitchell had indicated. How big the teacher looked as he turned toward her, so broad, and tall, and a little clumsy in a way that was nice. How pleasant, too, his face was, firm and very decided, yet quiet and kind. Oh, she could trust this young man! She began to pour forth her story.

He listened with an interest that made her feel as if a lot of his thoughts were really reaching back of the Morgans themselves.

"So we're here," she concluded. "And I am determined about one thing. We are going to learn to farm. If you could persuade my brother to go back to high school in the fall and take your regular course in vocational agriculture — "

"He's interested in farming?"

"Not the way he ought to be," replied Sayre with characteristic candor. "But he won't hate studying it the way he did some of the things he used to have to take in school. It's football, though, you'll have to get him with. He's an awfully good player. It's his legs."

"What about his legs?"

"They're football legs, halfback's. Hard to tackle; have to be tackled so low down that the other team's men are afraid of them. They're short, you see, below the knee, and strong. Yet Charley's awfully quick."

"He's played before?"

"Oh, my, yes! He was star halfback last year on West End High School team. In Chicago, you know, where we lived last. But he quit school at Christmas. Dad felt dreadfully, he'd always hoped one of us at least could get an education. But Charley said that even for football he couldn't stick some of the stuff they made him take. Yet he isn't stupid. When he wants to be, Charley's smart. Like building over that old Ford he got for twenty dollars' worth of work so that we all came out here in it without a bit of trouble."

"I'll certainly look the boy up and see what I can do."

Sayre moved to the edge of her chair, alight with gratitude. "If you can just get him interested," she breathed. "When Charley's interested, he can do anything. And how he will work! But" — Sayre's intensity broke — "it isn't easy to keep him staying interested.

"I can try." The teacher's slow smile was "nice."

"And you won't let him know about my coming to you? He'd be furious. He hates my managing him!"

"Never. Trust me for that. As for that Parsons eighty you're on, there are twenty acres of alfalfa on that farm that are better than almost anything else in that locality; and a lot of the alkali on the rest is the result of overwatering. In time, when the Government completes its new drainage system — "

But Sayre was nerving herself to her next question. "That — that part-time agriculture class you're going to start in November. Could a girl join it?"

The teacher stared at her in what was plainly astonishment. "Oh, I shouldn't think so," he said quickly. "At least, it's never been done — never even been asked for."

"But," the girl put in eagerly, "there's no rule against it?"

"Not that I ever heard. You see, the course has never been given here before. But my plan, the one I laid before the school board, didn't take girls into consideration at all, I'm afraid!" And he laughed a little apologetically. "It never occurred to me that any girl would want to join the group. There's too much physical labor involved, in the first place, in what we agricultural people call 'projects.' They are genuine farm enterprises on a big enough scale to be real business undertakings. The pupils will have to do practically all the work themselves: plowing, planting, cultivating, harvesting, and marketing or feeding, in a crops project like, say, five acres of field peas. Or all the care of the stock: breeding, rationing, marketing, raising the feed, and perhaps even providing quarters if necessary, in an animal project, like a dozen beef steers. You see, a lot of that sort of work would be much too hard for a girl!"

But even as she watched and listened, Sayre was conscious of a curious new look coming into Mr. Kitchell's eyes — as if, almost, he were sizing her up, and wondering. . . . She leaned forward as he paused, her eager face with its big eyes, deep Celtic blue in color, radiant with self-confidence. "Please, I could try. Even if I'm not big. I'm strong, and I'm used to hard work. All my life I've wanted so much to live in the country and work out of doors!"

"Oh, I'm sure you would do your best," he returned courteously. "Still, no girl I've ever heard of even thought of tackling such work."

"But nowadays," she broke in, "there isn't anything a boy does that a girl can't do. You know that!"

"We—e—e—ll" — was he giving in? — "personally I should have no objection. And I suppose that I could make it all right with the board. You yourself might put in a word with Mr. Nels Hansen. He's a neighbor of yours, and one of the board members. There's no better natural farmer on the whole Pawaukee."

A little later a buoyant Sayre awaited her brother's coming in the old Rattleshake, one who strove to keep Charley from detecting her mood as they chugged homeward side by side.

"Isn't this country a fade-out, Sayre? Small wonder more'n half the claims out our way from town are abandoned. Turn your goggles towards that specimen."

Reluctantly Sayre's glance followed Charley's gesture toward a miserable, isolated clutter of tarpaper shacks, by no means unique in the outlying landscape. Under the desert sun they seemed visibly shriveling into ruin. Around them swept dead acres, not only bare of any green spear of a cultivated crop, but now so white with encrusted alkali that even the original dwarf sagebrush and scrub cactus had vanished.

"They're not all like that," Sayre protested. "Out the other side of Upham there are some mighty nice-looking farms, with alfalfa fields, and beans, and field peas, and even a little wheat."

Sayre's quickness at having learned the local crops brought no approval from Charley. "And who owns 'em? Men like that Mr. Hoskins, who earn their living in town. And talk about getting them free! When the Government's got to be paid back for all the cost of building the big dam and the canals and the ditches and the headgates and the flumes and all the rest of the whole irrigation system that brings the water here? Sounds easy because the paying has to be done only little by little every year for forty years. But do you know, Sayre, there's hardly a farmer around who's been able yet to pay the Government anything at all? Even that Hoskins can't pay on the land he owns, and he's the biggest man in Upham. Some folks say, though, that he can't pay just because he's so good to the settlers about store credit and lending money."

Sayre tried not to show how hard she was listening. Charley sounded so superiorly informed that she did not want to flatter him with too much interest. He never even noticed her attitude. "But it's none of our worries," he concluded. "I've got something better to think about. I've landed a job. Two of them, if you want to know."

"A job? What kind?" Not on a farm. She knew that by the way he told of it.

Charley ignored the metallic quality in Sayre's tone. "General handy man in a garage at a dollar and a half a day. Washing tourist cars, mostly, for a while, I suppose. But I'll soon work up to being a mechanic. Showed the boss this junk pile. Told him how I'd rebuilt it to bring the Morgan tribe out to this Paradise."

"Of course you told him it brought you out here to be a farmer?"

Charley ignored his sister's sarcasm. "Grubbing out my days on these cactus flats? Not Charley. Now, a garage in a town like Upham — so near to Yellowstone Park, with tourists going through all the time — is a live place. Before long, when I've worked up — "

"So that's the latest, is it? A mechanic? Last fall it was a professional athlete. This spring an engineer. But for six whole weeks now all you've been able to talk about was the farmer you would make. That's what you came out here for, wasn't it? If I were a boy, I'd make up my mind once and for all what I was going to be. Then I'd stick, and I'd work, even if it killed me. Then, maybe, I'd get somewhere, even if I were a Morgan."

Charley lurched away from his sister in a half-crouching, entirely good-natured gesture of mock fear. Then he lapsed into silence, not of anger, but of complete unconcern. That was always the way with Charley. He wouldn't be half so exasperating or so hopeless if he'd only get mad.

Before the 'Shake had covered another mile, Charley was his affable self once more. "Guess maybe I can swing Dad down into my other job."

"What other job?"

"Told you I landed two, didn't I? Got this one first, awfully easy, too, before I went to the garage. Nothing but half-day clerking in Hoskins' general store. Dad could take that job, instead of me. Five dollars a week to be paid from the store's stock. Still it would keep him partly busy while we've got to stick around here. We can't get away without a cent, can we? And asking Aunt Mehitable for money to move with again right away won't go. What's eating you, Sayre? I'm darn lucky to have bagged these jobs!"

Sayre checked the retort that sprang to her lips. Here she was, furious because he had not got a job on a farm as she had intended he should until time for school to begin. Unreasonable? If it were, she was not going to acknowledge it. Bossing things that weren't any of her business was, of course, what he was always accusing her of doing. Oh, but this was her business. Only, he didn't know it!

Sayre did not like to own that she was not always fair to Charley. Getting those jobs, scarce as jobs must be around here, was so like his energetic, cheery, irresistible self. "If only he were as good at sticking as he is at getting," she thought vindictively. She studied her brother a little out of the corner of her eye. The face above that short, compact, sturdy body was decidedly good-looking, and its bright, genial expression made it still more attractive. Yet something about it was a little too loose. She did wish Charley's face had more of that quiet, firm look there had been on the agriculture teacher's.

Mentally she went right on making her own plans. That evening something happened that helped them out. Their neighbor, Mr. Nels Hansen, prompted by kindly curiosity, dropped in for a welcoming chat with Dad.

Big, raw-boned fellow that he was, they all warmed to him at once because of the sympathy with which he listened to their story. His interest reminded Sayre of Mr. Kitchell's; it went deeper somehow, than the mere Morgan part of the story. He and Dad were seated on the railless back step where shy Hitty had consented to be perched upon the visitor's big knees. Sayre was watching and listening from the doorway behind, while Charley lay sprawled on the gray ground beyond.

"You stick!" the monotonous voice of the visitor counseled. "You can make it to live here dis vinter if you can get a leetle yob."

"I've got the job," Charley announced, and told him about the garage.

"Dat, I t'ank, is only a summer yob. Ven Yellowstone Park shuts up for de vinter and no more tourists ride into Upham and out vonce more, de garage has not much business."

Inwardly mean enough to be exultant, Sayre watched the cloud descend over Charley's mobile face.

"And you haf dat good alfalfa," the visitor went on slyly.

"He wants to find out something," Sayre surmised. Aloud she burst impulsively into the conversation. "Oh, that isn't ours this year, except enough for a head or two of stock. Mr. Parsons owes it for a debt. But next year'll be different."

"I haf a cow," the visitor's voice droned on. "I do not need it and nobody vill buy it. It milks easy. I vill rent it to you for feeding it. I vould like my cow" — the monotone broke into a sudden, irresistible chuckle — "to eat dat alfalfa!"

"What a queer speech," Sayre thought. "Why our alfalfa especially? I believe he likes to say things like that just to puzzle people." Aloud she asked, "Why?"

The tow head nodded sagely. "Yust for fun. Ve haf maybe de beginning of a little fight on alfalfa now in dis country. Ven you stay here, maybe you, too, can get into dat fight."

Was he offering them a privilege? Sayre's blue eyes bubbled with laughter. Well, being "in" things was what she had always wanted for the insignificant Morgans.

The bargaining going on between Mr. Hansen and her father was making her light-hearted. If Dad would work for Mr. Hansen in his spare time that fall during harvest, Mr. Hansen would pay him in winter stores. "I haf no money, but I haf plenty chickens and plenty garden; potatoes, cabbage, carrots, onions, squash, navy beans — plenty to eat. And ve ain't shipping it much yet."

"And he's one of the best natural farmers on the Pawaukee," Sayre's memory quoted.

That night after their visitor had gone Sayre wrote a long letter to Aunt Mehitable all about everything. It contained the following paragraphs:

"Things don't look quite so bad tonight as they did yesterday. Perhaps if Charley and I can manage to go back to school again, even Dad may grow to feel that our coming out here was not such a 'crushing mistake.' That's what he calls it now. He's awfully blue, of course. But I'm not. I've got too many interesting things to learn and do.

"I've got my heart set on getting into that part-time class. I'm going to see that Mr. Hansen who called tonight to talk to him about it when Charley isn't around. He's important on the school board. And I think he liked me. Besides, if Mr. Hoskins doesn't want me, and I'm pretty sure he won't, I think Mr. Hansen will work hard to get me in, because Mr. Kitchell's willing.

"I like Mr. Kitchell a lot, Aunt Hitty, and I did not like Mr. Hoskins a bit. So I've about decided that when I go to school I won't try for that alfalfa prize even if it is one hundred and fifty dollars. I hope Charley won't. Probably the Hoskins boy will get it anyway. It was plain that his father meant him to."

And her letter ended with these words:

"Anyhow, it looks as if we were settled out here for a while, at least. It isn't starting exactly the way we expected, you see, and Dad is still terribly disappointed. But I'm doing my best to manage things so that Charley will give up his garage job the first of September, and enter high school in the regular vocational agriculture course. Then, if I can just get myself into the new, extra part-time agriculture class, which begins in November, and is meant for people like me who can't go to school for the full regular school year — Oh, we've just got to stay here, Aunt Mehitable, for two years at least! In that time Charley could graduate from high school, and I could finish the part-time course."

3

3

The Plan Begins to Work

THE BUSY, satisfying weeks of late summer and early fall flew by for Sayre with amazing speed. Things seemed to go almost too well. How she worked! But nearly all she did was fun.

Charley had "swung Dad down" into the afternoon job at the Hoskins store with surprising ease, almost as if Mr. Hoskins really wanted a Morgan in his employ, newcomers though the Morgans were in this hard-pressed community where so many people needed work. Dad was happy in that store; he liked the sociability of it. He received his pay every Saturday night in five dollars' worth of store supplies: flour, sugar, coffee, rice, kerosene, gas, articles of any kind of merchandise the family happened most to need. It was fun each week-end for them all with heads close together to figure out just what he had better get.

Mornings, most of the time, Dad worked for Nels Hansen, taking his pay in supplies from the flourishing Hansen fields and vegetable garden. Some of these vegetables Sayre canned; the rest she stored in the root cellar that Dad found time to dig according to Mr. Hansen's directions.

Taking Hitty with her, Sayre, too, worked for the Hansens for ten days when Mrs. Hansen's new baby came, her pay being pullet hens; the Morgans would have eggs that winter.

In the same way, through Mrs. Hansen's recommendation, Sayre did an occasional day's work here and there on neighboring farms during the time when Mr. Hoskins' big baler and its crew were busy baling the Pawaukee Irrigation Project's one big crop, alfalfa hay. She learned lots of things as she worked: how, for instance, in a community like this, without ever having any real money, to live comfortably, in many ways better than they often had lived in the city; how to cook navy beans deliciously at this high altitude; how to bake in the altitude, also, so that muffins and cakes would not fall, and bread would be light. All this was fun.

When the weather grew cool, as it does early in that country, Charley took what he had saved of his garage earnings and bought soft coal from the surface mines not many miles away. The coal was cheap; renting the truck to haul it cost as much as the coal itself. Charley and Dad stored it in one end of an open shed. There the white kitten that Hitty had found to mother cavorted over the pile gayly at all hours until its coat was more black than white. Hitty's loving arms never rejected her pet because of that; she lugged it around and hugged it close until her clothes were often a sight to behold. To Sayre that was not so much fun. It sometimes made her decidedly cross.

She really had almost too much to do for a seventeen-year-old girl these days, for in between times she was sewing: mending, patching and making over until the Morgan wardrobes, if not all they might be, were at least whole and warm. Then Aunt Mehitable's fall box came, full of plain practical things to help out. The prettiest thing it held was a new school dress for Sayre, blue just the shade of her eyes, the most becoming dress she had ever had. She was immensely happy over it.

She often felt thankful that she was so busy through the summer months; it kept her from worrying too much over what September would bring in the way of the need for decisions. Need for decision by Dad. Was he well enough satisfied with his job at the store to be willing to stay on, or would he get to talking about moving again? Need for decision by Charley. When the garage job was over would he want to find another? Or, would Mr. Kitchell be able to fulfill her hope by persuading Charley to give up work and enter high school? She was worried, too, by the silent unconcern with which Charley greeted every mention of her own plan to enrol in the part-time class in November. Indifference was his way of expressing disapproval, of course. Thank goodness, she would not have to rely upon Charley's 'Shake to take her back and forth when part-time class began. The part-time pupils were to be collected and carried home daily by a school bus.

Then came the last Saturday in August, with Charley coming home and announcing, "The garage job's ended." Well, that was hardly news; they had known for a week that the proprietor would not need him much longer. This was not, apparently, his real news. He paused in front of his sister, who was sewing, to add with a carelessness behind which lurked both apology and defiance: "And Monday morning I'm starting into school again at Upham High School. Junior. Specializing in vocational Ag. Got acquainted with the Ag teacher. He's been coming into the garage lately, and I've been working on his car. He's a dandy guy — I sure like him. And he says they need a good half-back pretty bad on the high school football team. A — a fellow's got to put in his time doing something."

For just a second Sayre looked up from the blue work shirt she was patching, while she tried to summon surprise into her face.

"Well," she conceded, "I suppose he has."

But acting a part was too unnatural for her to dare to keep up the attempt. She escaped back into concentration upon her work, stifling her desire to laugh. She knew perfectly well that Charley had expected from her a tirade about his changeableness. Later she had a most enjoyable private giggle over the situation. Charley was going to high school, after all!

Charley took to it too, better than she had dared hope. If at home he was soon talking more about the football team than about his lessons, he was keen about the farm shop work. There was a class project under way there that greatly interested him, the converting of a large, old touring car into a commodious bus to carry the part-time pupils back and forth to school when the part-time agriculture class should begin. Charley worked a good many voluntary hours on the job.

"I'd give my hat," he remarked once to Sayre, "to find out who's going to get to drive that bus."

"Mr. Hansen might know," she suggested slyly.

So the first Monday morning in November rolled around, the date set for the part-time agriculture class to begin. Sayre, up since dawn, wiped and set in the sun the pail that had held the milk from the Hansen-Morgan cow. She had put up the lunches and had got little Hitty ready for her usual morning at the primary school. Now there was nothing left to do but change her own dress. "I'll be ready when you are, Charley."

Her brother lifted the refilled water pail to the bench near the door. "What you going to do with the kid after primary hours?" He did not look at Sayre.

"I'll manage." If Charley could be exasperating, so could she. If he had any sense he would know that Dad would keep Hitty with him afternoons in the store until Sayre's school was out. Charley had been silent all morning with that horrid indifference of his. Sayre understood it, of course. It was not until the last minute that he had accepted the fact that she had meant what she had said about going to school. His attitude made her furious. She had tried hard to take Mother's place as best she could ever since that dreadful day three years ago when Mother had died; but this did not give Charley the right to act as if it were his mother who wanted to go to school with him. Wasn't she his twin, exactly the same age as he was?

Why couldn't he act about her new plan the way dear old Dad did? "If you can find any way, Sayre," he had told her some weeks before, "to make up for my neglect of you in the matter of education, no one will be more pleased than your father." At which Charley had whistled a bar of "Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie." Sayre shut her mouth tight. She would have to watch out to keep that quick tongue of hers from defeating her own ends!

Now Charley was bringing the car up for her and Hitty. But this time it was not the old Rattleshake. What Charley was driving so proudly was the improvised school bus. After all, there was stuff in Charley! The school board would never have appointed him the driver of this bus if some of its members had not believed in him. And they had even entrusted him with the care of it at night, so that it was kept at the Morgans'. This bus work was a pay job, too.

For the next three weeks, however, while the football season lasted, Charley would not be able to drive the bus home in the afternoons. He would have to stay after school for football practice, and come home at supper time with dad in the 'Shake. Young Nels Hansen, although slightly under age, had been given a permit to act for those three weeks as Charley's afternoon supply, and drive the bus home each day after school at four o'clock.

"Glad to take you in, Sayre, of course," Charley was saying. "But your going's simply crazy. You're a girl. They'll never let you register. Not in Ag."

"I can try anyhow." Sayre dropped her eyes in a demure gesture which hid the gleam of triumph behind the long, dark lashes. She had paved the way for what she was doing better than he knew.

The bus began to pick the part-time pupils up in small groups at the cross roads. All but two or three came from the foreign element among the settlers. In this Sayre read Nels Hansen's influence, just as she read it in other things that had to do with school affairs. At one stop two stolid-looking fellows mounted the bus steps with heavy deliberation. Their round, visorless caps and the shapeless cut of their home-made clothes showed that they belonged to that clannish colony of German-Russian sugar-beet growers who the spring before had settled on some of the abandoned claims between Upham and Nels Hansen's.

"Hello, Ivan. So you got Boris to come. Bully for you!" Charley waved his hand cordially at the newcomers.

Light kindled in the wide, patient faces.

"Yess." "Goot morning." The careful gutturals were warm with friendliness. Shy uplifted eyes beamed at the young bus driver.

"He actually knows them," Sayre thought. After all, was there ever anyone like Charley, so friendly to everybody? Or as darling as Hitty? The little girl was smiling coyly at the last comers from out the refuge of Sayre's arms.

But Sayre did not smile at them. A sudden thought had gripped her with a puzzled sense of injustice. Could foreigners like these, if they were naturalized citizens, homestead on new land when her own father could not? Only at some such rare instant did Sayre any longer pause to realize that she and Charley were setting out to learn to farm on land to which they had no legal right; so like a home had Parsons' eighty already begun to seem to her.

Her hardest moment in that first school day came early, at the joint meeting that Mr. Kitchell called of all Ag pupils of both groups, regular and part-time. She was the last to enter the room. Just over the threshold she paused. All around her she sensed hostility. It took the breath from her like a cold plunge; color mounted into her cheeks. Then she thrust her head high, moved sturdily across the room, and seated herself, not next to Charley, but among the foreigners. They might be just as unfavorably disposed as the others toward having a girl in their midst, but they were too submissively impressed by their surroundings to show their feelings so plainly. Of all the glances that came Sayre's way none was more hostile than the dark, brooding stare of the Hoskins boy. She eyed Mr. Kitchell nervously. To her relief he acted as if there were nothing unusual in the situation.

After the meeting was over she approached his desk. "I can stay then? Even if I am a girl? The board's willing?"

She knew nothing of the eager brightness of her own face above the becoming new blue dress. She did know that the teacher's half-playful nod and slow, cordial smile were full consent. She could scarcely wait for the moment when she could triumph over Charley. Before it arrived, however, another incident had overshadowed her sense of triumph.

All that first day at school Sayre had been much impressed by the difference in spirit between the serious part-time pupils and the light-hearted youngsters of the regular four-year courses. She watched the latter darting in and out and everywhere about the school building in an irresponsible casual goodfellowship which she secretly envied. She began to understand how Charley felt about this new school venture of hers. When school was out at four o'clock a thin, red-haired girl opened her eyes more fully.

"You're Charley Morgan's sister, aren't you? I'm Irene Osgood. Rene for short. Wouldn't you like to go and watch football practice for a while?"

Sayre accepted gratefully. She would not go back in the bus of the morning. There were beans and a custard cooked for supper; Dad had Hitty; she would wait for Dad and Charley and they could all go home together in the 'Shake.

Together Sayre and her companion walked toward the big athletic field. It felt good to Sayre to have some girl companionship. There had been so little time for it in her life these last three years.

"I think it's simply horrid," the other girl burst out suddenly, "The way the regular pupils feel about you part-time ones! I don't see what there is about us to make us feel so superior. I think you're perfectly splendid to do what you're doing." (Sayre began to feel uncomfortable. Whatever this girl was, she was a gusher, and she had absolutely no tact!) "I told Charley he ought to be ashamed to mind about your coming in. The fellows'll just razz him all the more if he shows so plain that he's sensitive. What I say is, he's only an Ag himself, if he is a full-time regular. But, of course, he can play football. And with Frank Hoskins in the Ag bunch, it's got social standing."

Sayre tried not to betray her distaste for this silly speech. The two girls were moving in the wake of several boys in football uniform, who were clumping along with that peculiar gait that is imposed by spiked shoes on uncongenial ground. Sayre suspected her companion of deliberately keeping close to these boys. Presently the short boy near the lead swung his head back toward the powerful fellow at his heels. Yes, that short fellow was Charley. Sayre could never be quite sure of his identity in those type-leveling togs. But the face framed by that dingy helmet was not Charley's usual one. This face had a glower. Sayre was suddenly glad that Charley's face could look like that. She saw him eye the big, burly lad behind him in unmistakable contempt. Then he spoke, making each syllable so distinct that even above the sounds of hurrying pupils thronged all around, Sayre caught every word.

"Once and for all, Frank Hoskins, never-you-mind-about-my-sister! Understand?"

Sayre could not hear whether the other fellow answered, but as he lagged back to join the boys at the rear, she had a glimpse of the face that his helmet encircled. It was sullen to vindictiveness, and it belonged to the first boy she had laid eyes on in Upham.

Meanwhile the girl at Sayre's side was prattling on. "Look, that's Frank Hoskins. Isn't he powerful? Not many high school teams can show a fellow as strong as that. He just about makes the team. He's full-back, you know, and by far the best player on it."

Sayre smiled. She was beginning to wonder whether this sharp-featured girl was as artless as she seemed.

The practice that afternoon was a scrimmage between two extemporized teams the coach had made up for a purpose which Sayre learned later. It seemed that the high school to be played the following Saturday had a half-back much like Charley in build, whose famed dodging Frank Hoskins would have to block. So today Charley was to play on one team and Frank Hoskins on the other. One play occurred often: it was Charley, carrying the ball, going through the line on an off-tackle play. Go through it he did again and again, his compact, darting, twisting form evading with swift adaptation and elusiveness Frank's dogged, determined lunging.

The coach kept shouting reprimands to Frank. "Lower! Lower, didn't I tell you? Nothing but a ground tackle'll get a fellow like Morgan!"

At last Frank did "get" Morgan in a play that was farther away from the rest of the teams than it should have been. Charley was downed at the side lines right at the spot behind which the girls were standing. That was how Sayre saw so plainly. It was a quick action for one of Frank's bulk — the way in which his big foot swung up to jam its kick straight into Charley's side as Charley lay screened from the other players' view by Frank's own big body.

Sayre's blue eyes flashed black. She leaned forward. "You — you c-contemptible c-c-coward!"

Instantly there jerked itself up to meet hers a heavy, sullen face; in it she read the leap of fear. The sight steadied her anger and her voice. "You needn't be so scared," she scoffed. "Nobody saw you but two girls. Charley won't tell. He's a game sport!"

But from a vantage point some distance away somebody else had seen. A moment later the coach's hand gripped Frank's shoulder with a power which twirled the big fellow around in the direction facing the school's gymnasium door. "March. Straight back to the dressing room, and take off that suit."

Surprised, cowed, and sullen, the boy stumbled forward in angry obedience out from the silent circle of boys which by this time had gathered thick about the scene.

Sayre heard the girl at her side mutter something about its being "mean to humiliate a boy like that right before everybody." But she did not address Sayre directly; nor did Sayre speak. Soon it appeared that Rene had lost interest in the practice, and she made an excuse to get away. Sayre wandered toward the Hoskins store, got Hitty, settled the child and herself in the 'Shake, and tried to study. Getting down to study was going to be a little hard for her, she realized, even when Hitty's restlessness and chatter were not close at hand.

At home that evening while Dad read Little Black Sambo aloud to Hitty, who was curled in his lap, Charley wiped the supper dishes for Sayre. All trace of the morning's feeling between the twins had vanished. Careful though both were not to speak of the matter, both were conscious that each, that afternoon had had sure proof of the other's loyalty.

"Saw you chumming with Frank Hoskins' girl."

"Frank Hoskins!" Sayre was concentrated scorn. "I hope the coach meant that that brute had to hand in his suit for good. Did he?"

"Aw — not exactly. You see, the fellow's a darn good player, and he's worked hard. And the coach sure gave him one bawling out after practice right before the whole squad about being jealous of me, and working too much for his own glory, and all that kind of stuff. Hoskins is a queer kid, you know. Always has to be 'it' at anything he's in. Usually is, too, I guess, 'cause he's smart. And — "

The reason for Charley's sudden volubility did not escape Sayre. Plunging both arms deep into the soapsuds and resting the palms of her hands on the dishpan's bottom, she faced her brother. "Charley Morgan," she divined, "you begged off for him."

Charley avoided his sister's gaze like a culprit. "Aw, well, we wouldn't have had a chance in the game next Saturday without him. And besides — "

"I knew it!" Sayre vigorously resumed her dishwashing. "All I've got to say is, I hope he appreciates what you've done for him."

Charley laughed. "Hoskins isn't exactly the sort to 'appreciate' favors from a fellow who's crowding him a little. Guess likely he's got it in for me worse'n ever."

Dish-water slopped and dishes clinked and rattled. "You see," Charley's big hands clumsily manipulated a towel around the edge of a cup, "it isn't only football between Hoskins and me. I guess he's sore at my telling the other Ag fellows that they won't catch me in that alfalfa contest of Hoskins' father, not considering the way Mr. Hansen says Mr. Kitchell really feels about it."

"Isn't Mr. Kitchell nice?" Sayre murmured cordially.

"Nice!" Charley scoffed at the ineffective word. "He's a prince, that fellow. Made of the right stuff all over and clear through, every darn inch of him."

Sayre poured the dish-water into a pail; then she swirled the dishcloth around the pan in happy content. If this hero-worship of Charley's only kept up, where might it not lead him?

Charley picked the pail up and carried it outside.

"Sayre." (So Dad had not been completely absorbed in Hitty and Black Sambo.) "Hadn't you and Charley better not be too independent? Remember that the father of this boy that Charley seems to be having trouble with, the man who offers that prize in the alfalfa contest, happens to be my employer."

Did Dad mean he wanted them to enter that contest? Sayre did not ask. "It's that Mr. Hoskins," she said to herself. "He's been hinting to Dad about our going into it." What luck that they had no five acres of land fit for a new alfalfa planting. Even a greenhorn like her knew that.

4

4

Projects

IN SPITE of the friction between its two best players, Upham High School won the next Saturday's football game, and the two games that followed. Then the season ended. Sayre was glad. Charley would not see so much of Frank Hoskins now, and also, he would have more time for his Ag work.

Nevertheless she sat up for Charley's homecoming on the night of the closing football banquet, at which next season's officials were to be chosen. "They elected you," she cried when he came in. She knew by the glow in his eyes.

"You see before you, Miss Morgan, next year's captain of the Upham High School football team!" How Charley did love making this announcement!

But Sayre's heart skipped a beat. Well, he deserved it, she supposed. Had not his playing brought the school the most successful season of its history? There was another comforting thought in the situation, too: it would take a good deal now to make Charley quit school. Yet it was true, also, that he was a newcomer, whereas Frank Hoskins had given the school three years of hard service. Queer, what a jumble of satisfaction and misgiving a person could get out of exactly the same happening!

Suddenly the misgiving dominated. "And Frank? How did he take it?" Sayre knew only too well after a month of school contacts that the failure of a Hoskins to attain a set desire was no trifling matter in that community.

Charley laughed in the way he always did of late when Sayre spoke of Frank Hoskins. "Well, he didn't congratulate me personally. But he made a speech. Said all the right things, in public, anyway. Some of the fellows say his father wrote it for him. Told him he'd got to make it if he lost the election. It sure sounded fine. Mr. Kitchell used a big word about it. Said it showed magnanimity."

Magnanimity! Sayre was to hear that characterization repeated often during the next few days; and she scoffed inwardly every time she heard it. For as the days went by she caught the reflection of Frank's real feeling from Rene Osgood's remarks. And she also saw Frank and Charley together without other witnesses.

Football interests began to recede into the background, however, and the girl became too absorbed in study and plans for projects to bother her head much about Frank Hoskins. Projects, in the sense in which Mr. Kitchell had explained them to Sayre on that first visit of hers to the school house, were now ever on the tongues of the vocational agriculture pupils of both part-time and full-time groups.

Dad was really the first Morgan to start a project. He was attending, chiefly for sociability, a series of ten evening classes on hog production which Mr. Kitchell was offering to adult farmers in the community. Much to Charley's and Sayre's amusement, he came home one night with a Hampshire sow in the back of the 'Shake.

"Where'd you get it?" Sayre queried.

"Bought it. On credit, of course. Mr. Hoskins very kindly endorsed my note."

The girl's mood hardened. "How much?"

"Well, it's a purebred; they're expensive, you know. Ei-eighty dollars."

"Eighty dollars!" Sayre was stunned.

She trusted to Mr. Hansen to do the chiding, as she knew he would when he heard of it. "I vould not let dat man Hoskins get no more rights on me, Meester Morgan. He likes dat too much."

"He isn't going to keep any rights on us," Sayre resolved. "We'll pay for that sow with its next season's litters, and that's the last we'll ever owe him. Charley and I must finance our projects some other way."

At last Sayre decided what her own projects were to be. The biggest was to be turkeys. This dry tableland was natural turkey country. Mr. Hansen was already beginning to develop substantial turkey markets for this section of the Pawaukee Project, so that now was just the time to go into the turkey business.