THE GIRL NEXT DOOR

THE GIRL NEXT DOOR

CHAPTER I

MARCIA'S SECRET

"MARCIA BRETT, do you mean to tell me – "

"Tell you – what?"

"That you 've had a secret two whole months and never told me about it yet? And I 'm your best friend!"

"I was waiting till you came to the city, Janet. I wanted to tell you; I did n't want to write it."

"Well, I 've been in the city twelve hours, and you never said a word about it till just now."

"But, Janet, we 've been sight-seeing ever since you arrived. You can't very well tell secrets when you 're sight-seeing, you know!"

"Well, you might have given me a hint about it long ago. You know we 've solemnly promised never to have any secrets from each other, and yet you 've had one two whole months!"

"No, Jan, I have n't had it quite as long as that. Honest! It did n't begin till quite a while after I came; in fact, not till about three or four weeks ago."

"Tell me all about it right away, then, and perhaps I 'll forgive you!"

The two girls cuddled up close to each other on the low couch by the open window and lowered their voices to a whisper. Through the warm darkness of the June night came the hum of a great city, a subdued, murmurous sound, strangely unfamiliar to one of the girls, who was in the city for the first time in all her country life. To the other the sound had some time since become an accustomed one. As they leaned their elbows on the sill and, chins in hand, stared out into the darkness, Marcia began:

"Well, Jan, I might as well commence at the beginning, so you 'll understand how it all happened. I 've been just crazy to tell you, but I 'm not good at letter-writing, and there 's such a lot to explain that I thought I 'd wait till your visit.

"You know, when we first moved to this apartment, last April, from 'way back in Northam, I was all excitement for a while just to be living in the city. Everything was so different. Really, I acted so silly – you would n't believe it! I used to run down to the front door half a dozen times a day, just to push the bell and see the door open all by itself! It seemed like something in a fairy-story. And for the longest while I could n't get used to the dumb-waiter or the steam-heat or the electric lights, and all that sort of thing. It is awfully different from our old-fashioned little Northam – now is n't it?"

"Yes, I feel just that way this minute," admitted Janet.

"And then, too," went on Marcia, "there were all the things outside to do and see – the trolleys and stores and parks and museums and the zoo! Aunt Minerva said I went around 'like a distracted chicken' for a while! And beside that, we used to have the greatest fun shopping for new furniture and things for this apartment. Hardly a bit of that big old furniture we brought with us would fit into it, these rooms are so much smaller than the ones in our old farm-house.

"Well, anyhow, for a while I was too busy and interested and excited to think of another thing –

"Yes, too busy to even write to me!" interrupted Janet. "I had about one letter in two weeks from you, those days. And you 'd promised to write every other day!"

"Oh well, never mind that now! You 'd have done the same, I guess. If you don't let me go on, I 'll never get to the secret! After a while, though, I got used to all the new things, and I 'd seen all the sights, and Aunt Minerva had finished all the furnishing except the curtains and draperies (she 's at that, yet!), and all of a sudden everything fell flat. I had n't begun my music-lessons, and there did n't seem to be a thing to do, or a single interest in life.

"The truth is, Jan, I was frightfully lonesome – for you!" Here Marcia felt her hand squeezed in the darkness. "Perhaps you don't realize it, but living in an apartment in a big city is the queerest thing! You don't know your neighbor that lives right across the hall. You don't know a soul in the house. And as far as I can see, you 're not likely to if you lived here fifty years! Nobody calls on you as they do on a new family in the country. Nobody seems to care a rap who you are, or whether you live or die, or anything. And would you believe it, Janet, there is n't another girl in this whole apartment, either older or younger than myself! No one but grown-ups.

"So you can see how awfully lonesome I 've been. And as Aunt Minerva had decided not to send me to high school till fall, I did n't have a chance to get acquainted with any one of my own age. Actually, it got so I did n't do much else but moon around and mark off the days till school in Northam closed and you could come. And, oh, I 'm so glad you 're here for the summer! Is n't it gorgeous!" She hugged her chum spasmodically.

"But to go on. I 'm telling you all this so you can see what led up to my doing what I did about – the secret. It began one awfully rainy afternoon last month. I 'd been for a walk in the wet, just for exercise, and when I came in, Aunt Minerva was out shopping. I had n't a new book to read nor a blessed thing to do, so I sat down right here by the window and got to thinking and wondering why things were so unevenly divided – why you, Jan, should have a mother and father and a big, jolly lot of brothers and sisters, and I should be just one, all alone, living with Aunt Minerva (though she 's lovely to me), with no mother, and a father away nearly all the time on his ship.

"And it seemed as if I just hated this apartment, with its little rooms, like cubbyholes, all in a row. I longed to be back in Northam. And looking out of the window, I even thought I 'd give anything to live in that big, rambling, dingy, old place next door, beyond the brick wall, for at least one could go up and down stairs to the different rooms.

"And then, if you 'll believe me, Jan, as I stared at that house it began to dawn on me that I 'd never really 'taken it in' before – that it was a very strange-looking old place. And because I did n't have another mortal thing to do, I just sat and stared at it as if I 'd never seen it before, and began to wonder and wonder about it. For there were a number of things about it that seemed decidedly queer."

"What 's it like, anyway?" questioned Janet. "There were so many other things to see to-day that I did n't notice it at all. And it 's so dark now I can't see a thing."

"Why, it 's a big, square, four-story brick house, and it 's terribly in need of paint. Looks as if it had n't had a coat in years and years. It stands 'way back from the street, in a sort of ragged, weedy garden, and there 's a high brick wall around the whole place, except for a heavy wooden gate at the front covered with ironwork. That gate is always closed. A stone walk runs from the gate to the front door. 'Way back at the rear of the garden is an old brick stable that looks as if it had n't been opened or used in years.

"You ll see all this yourself, Janet, when you look out of the window in the morning. For this apartment-house runs along close to the brick wall, and as we 're three floors up, you get a good view of the whole place. This window in my room is the very best place of all to see it – fortunately.

"But the queer thing about it is that, though the shutters are all tightly closed or bowed, – every one! – and the whole place looks deserted, it really is n't! There 's some one living in it; and once in a long while you happen to see signs of it. For instance, that very afternoon I saw this: 'most all the shutters are tightly closed, but on the second floor they are usually just bowed. And that day the slats in one of them were open, and I thought I could see a muslin curtain flapping behind it. But while I was looking, the fingers of a hand suddenly appeared between the slats and snapped them shut with a jerk.

"Of course, there 's nothing so awfully strange about a thing like that, as a rule, but somehow the way it was done seemed mysterious. I can't explain just why. Anyhow, as I had n't anything else to do, I concluded I 'd sit there for a while longer and see if something else would happen. But nothing did – not for nearly an hour; and I was getting tired of the thing and just going to get up and go away when – "

"What?" breathed Janet, in an excited whisper.

"The big front door opened (it was nearly dark by that time) and out crept the queerest little figure! It appeared to be a little old woman all dressed in dingy black clothes that looked as if they must have come out of the ark, they were so old-fashioned! Her hat was a queer little bonnet, with no trimming except a heavy black veil that came down over her face. She had a small market-basket on her arm, and a big old umbrella.

"But the queerest thing was the way she scuttled down the path to the gate, like a frightened rabbit, turning her head from side to side, as if she was afraid of being seen or watched. When she got to the gate, she had to put down her basket and umbrella and use both hands to unlock it with a huge key. When she got outside of it, on the street, she shut the gate behind her, and of course I could n't see her any more.

"Well, it set me to wondering and wondering what the story of that queer old house and queer little old lady could be. It seemed as if there must be some story about it, or some explanation; for, you see, it 's a big place, and evidently at one time must have been very handsome. And it stands right here in one of the busiest and most valuable parts of the city.

"The more I thought of it, the more curious I grew. But the worst of it was that I did n't know a soul who could tell me the least thing about it. Aunt Minerva could n't, of course, and I was n't acquainted with another person in the city. It just seemed as if I must find some explanation. Then, all of a sudden, I thought of our new colored maid. Perhaps she might have heard something about it. I made up my mind I 'd go right out to the kitchen. So I went and started her talking about things in general and finally asked her if she knew anything about that old house. And then – I wish you could have heard her! I can't tell it all the way she did, but this is the substance of it:

"It seems that she 's discovered that the janitor here is the son of an old friend from North Carolina. Of course she 's been talking to him a lot, and he has told her all about the whole neighborhood, and especially about the queer old house next door. He says it 's known all around here as 'Benedict's Folly.' "

"Why?" queried Janet.

"Well, because years and years ago, when the owner built it (his name was Benedict), it was 'way out of the city limits, and everybody thought he was awfully foolish, going so far, and building a handsome city house off in the wilderness. But he was n't so foolish after all, for the city came right up and surrounded him in the end, and the property is worth no end of money now.

"But here 's the queer thing about it. Old Mr. Benedict 's been dead many years, and the place looks as if no one lived there – but some one does! It 's a daughter of his, a queer little old lady, who keeps herself shut up there all the time; some think she 's alone, others say no, that some one else is there with her. No one seems to know definitely. Anyhow, although she is very wealthy, she does all the work herself, and the marketing; and she even carries home all the things, and won't allow a single one of the tradesmen to come in.

"Mr. Simmonds (that 's our janitor) says that two years ago, in the winter, a water-pipe there burst, and Miss Benedict just had to get a plumber; and he afterward told awfully peculiar things about the way the house looked, – the furniture all draped and covered up, and even the pictures on the walls covered, too, – and not a single modern improvement except the running water and some old-fashioned gas-fixtures. And the little old lady never raised her veil while he was there, so he could n't see what she looked like.

"Mr. Simmonds says every one thinks there is some great mystery about 'Benedict's Folly,' but no one seems to be able to guess what it can be. Now, Janet, is n't that just fascinating? Think of living next door to a mystery!"

"It 's simply thrilling!" sighed Janet. "But, Marcia, I still don't see what this has to do with a secret. Where do you come in? I don't see why you could n't have written all this to me."

"Wait!" said Marcia. "I have n't finished yet. That was absolutely all I could get out of our maid Eliza, all she or any one else knew, in fact. But as you can imagine, I could n't get the thing out of my mind, and I could n't stop looking at the old place, either. I tried to talk to Aunt Minerva about it, but she was n't a bit interested. Said she could n't understand how any one could keep house in that slovenly fashion, and that 's all she would say. So I gave up trying to interest her.

"Now, I must tell you the odd thing that happened that very night. You know I 've said it was raining hard all that day, and by ten o'clock the wind was blowing a gale. I was just ready for bed, and had turned off my light and raised the shade, when I thought I 'd take another peep at my mysterious mansion across the fence. All I could see, however, were just some streaks of light through the chinks in the shutters in that one room on the second floor. All the rest of the place was as dark as a pocket. And as I sat staring out, it suddenly came to me what fun it would be to try to unravel the whole mysterious affair all by myself. It would certainly help me to pass the dull days till you came!

"But then, too, the only way to do it would be to watch this old place like a cat, and I knew that would n't be right. It would be too much like spying into your neighbor's affairs, and, of course, that 's horrid. Finally, I concluded, that if I could do it without being meddlesome or prying, I 'd just watch the place a little and see if anything interesting would happen. And while I was thinking this, a strange thing did happen – that very minute!

"The wind had grown terrific, and, all of a sudden, it just took one of the shutters of that lighted room, and ripped it from its fastening, and threw it back against the wall. And the next moment a figure hurried to the window, leaned out, and drew the shutter back in place again. But just for one instant I had caught a glimpse of the whole inside of the room! And what do you suppose I saw, Jan?"

"What?" demanded Janet.

"Well, not much of the furnishing, except a lighted oil-lamp on a table. But, directly in the center of the room, in a perfectly enormous armchair sat – a woman! And it was n't the one I 'd seen in the afternoon, either. I 'm sure of that. I could n't see her face, for it was in shadow, but she was looking down at something spread out on her lap. And she held her right hand over it in the air and waved it back and forth, sort of uncertainly. You can't imagine what a strange picture it was – and then the shutter was closed. There was something so weird about it all.

"If I was curious before, I was simply wild with interest then. It seemed as if I must know what it all meant – what that strange old lady could be doing, sitting there in state in the middle of the room, and all the rest of it. You don't blame me, do you, Jan?"

"Indeed I don't! I 'd be ten times worse, I guess. But what about the secret? And did you find out anything else?"

"Yes, I did. And that 's the secret. The whole mysterious thing is in the secret, because no one but you knows I 'm the least interested in the affair, and I don't want them to – now! I 'll tell you what happened next."

But just at this moment they were interrupted by a knock at the door, and a voice inquiring:

"Girls, girls! have n't you gone to bed yet? I 've heard you talking for the last hour."

"No, Aunt Minerva!" answered Marcia, "we are sitting by the window."

"Well, you must go to bed at once! It 's nearly midnight. You won't either of you be fit for a thing to-morrow. Now, mind, not another Word! Good-night!"

"Good-night!" they both answered, but heaved a sigh when Aunt Minerva was out of hearing.

"It 's no use!" whispered Marcia. "We 'll have to stop for to-night. But there 's lots more, and the most interesting part of it, too. Well, never mind, I 'll tell you all the rest to-morrow!"

CHAPTER II

THE FACE BEHIND THE SHUTTER

JANET had no sooner hopped out of bed next morning than she flew to the window to examine "Benedict's Folly" by broad daylight. In the streaming sun of a June morning the dingy old mansion certainly bore out the truth of Marcia's mysterious description.

"Gracious! I should think you would have been interested in it from the first!" she exclaimed.

"Interested in what?" yawned Marcia, sleepily, opening her eyes.

"'Benedict's Folly,' of course! Let 's see," went on Janet, who possessed a very practical, orderly mind; "from your story last night it seems there must be two people living there – but look here! how did you know, Marcia, that it was another old lady you saw that night when the shutter blew open?"

"Why, for several reasons," answered Marcia. "In the first place, the one who goes out is short and slight. The one sitting in the chair was evidently large, and rather stout, and – and different, somehow, although I did n't see either of their faces. And then, it was n't the lady in the chair who closed the shutter. She evidently never moved. So it must have been some one else."

"Yes, it must have been," agreed Janet, convinced. "Queer that nobody seems to know about the second one. I wonder who she is? And are there any more? Go on with your story, Marcia."

"No," said Marcia. "Wait till we can be by ourselves for a long while. I don't want to be interrupted. Aunt Minerva 's going out this morning, and then we 'll have a chance."

So, later in the morning, the two girls sat by Marcia's window, each occupied with a dainty bit of embroidery, and Marcia began anew:

"Well, after that rainy night, for several days I did n't see a thing more that was interesting about the old house or the queer people who live in it. I used to watch once in a while to see if the little lady in black would go out again in the afternoon, as she did before, but she did n't. Then, a day or two later, I did something that surprised even myself, for I had n't the faintest intention of doing it. I had been taking a walk that afternoon and was just coming home, passing on the way the high brick wall of the Benedict house. It was just as I reached the closed gate that an idea popped into my head.

"You know, they say that no visitors are ever admitted, and no rings or knocks at the gate are ever answered. Well, something suddenly prompted me to ring that bell and see what would happen. I never stopped to ask myself what I should say if some one came and inquired what I wanted. I just rang it suddenly (and I had to pull hard, the old thing was so rusty) and far away somewhere in the house I heard a faint tinkle.

"Then I got kind of panic-stricken, wondering what I 'd say if any one did really come. But I need n't have worried, for what do you suppose happened?"

"Nothing!" answered Janet, promptly.

"That 's just where you 're mistaken; but you 'd never guess what it was. About a minute after I 'd rung the bell, I heard light footsteps on the walk behind the gate. But, instead of coming toward the gate, they were hurrying away from it; and in another minute I heard the front door close. After that it was all quiet, and nothing else happened. Then I went on home."

"I know," interrupted Janet, whose quick mind had already worked out the problem, "exactly what occurred. It was Miss Benedict, who had been just about to come out on her way to do the marketing. And your ring frightened her, and sent her hurrying back into the house. Is n't it all singular!"

"Yes, that must have been it," agreed Marcia. "And it made me more curious than ever to understand about it. And I was so annoyed at myself for ringing at all. If I had n't, I might have seen Miss Benedict close by, when she came out of the gate. It served me right for doing such a thing, anyhow!

"But after that I got to watching, every time I went out, thinking I might see her on the street somewhere, especially if it was about the time she usually did her marketing – along toward dusk. Several days passed, however, and I never did. I had thought of watching from my window to see when she went out, and then following her. But that did n't seem right, somehow. It would be too much like spying on her. So I just concluded I 'd trust to chance. And luck favored me at last, one morning, about a week after I 'd rung her bell.

"It happened that the night before, Eliza suddenly discovered we were all out of oatmeal for breakfast, and I promised her I 'd get some very early in the morning, when I went to take my walk. You know, I 've found that on these warm summer days in the city it 's much pleasanter to take a walk in the real early morning than to wait till later in the day, when it 's crowded and hot. And I always used to love walking in the early morning, up in Northam.

"Well, anyhow, I got up that day about six. I knew that no stores near here would be open so early, and I decided to walk over toward the other side of town. It 's a sort of poor section there, and the stores often open up quite early, so that folks can do their marketing before they go to work. It was a beautiful, cool morning, and I was quite enjoying myself when – Jan, what do you think? – I looked up, and about half a block ahead of me was a little black figure with a market-basket, hurrying along. I knew it was Miss Benedict!

"Can you imagine my surprise – and delight? I suddenly made up my mind I 'd keep behind her, and go into the same store she did. There could surely be no harm in that! And by and by I saw her turn into a little grocery-shop; and a minute or two after in I walked, went to the counter, and stood right near her. There was no one in the store beside ourselves and the grocer. He looked sleepy, and was yawning while he wrapped up something for her. He asked me to 'Wait a minute, please!' which, of course, I was only too delighted to do, as it gave me a perfect right to stand close by my mysterious little neighbor and hear her speak.

"And it was right there, Janet, that I got the surprise of my life. She still wore her black veil, and it was so thick that not a bit of her face could be seen. Her dress was the most old-fashioned thing – it looked twenty years old, if not more. I don't know what sort of a voice I had expected to hear, but it was nothing in the least like what I did hear.

"I can't exactly describe it to you, Jan, but it was the most beautiful speaking voice I 've ever heard in my life! It was soft, and flute-like, and so – so appealing! It somehow went straight to my heart. It made me feel as if I wanted to take care of Miss Benedict, somehow, I can't exactly explain it. Even when she was speaking of such commonplace things as butter and eggs and sugar, it was like – like music!

"Well, in a few moments she had finished, and the grocer packed her things in her basket, and she went away. I had to stay, of course, and get my oatmeal, and I did n't see her again. But being so close to her and hearing that lovely voice had changed my whole feeling about her. At first, I had just been interested and awfully curious about the whole mysterious affair, and, I 'll confess, just a wee bit repelled by the account of the queer little lady and the strange way she lived. I wanted to know the explanation of the mystery, but I did n't particularly want to know her. But after that, I felt different, – sort of bewitched by that beautiful voice. I wanted to help that Miss Benedict. I wanted to do something for her, or try to make her happier, or – or something, I could n't quite explain what. And I wanted – oh, so much! – to see her face, and know what she was like, and more about herself. Can you understand, Jan?"

"Indeed, I can. But do go on. Did you ever meet her again?"

"No, I did n't. But I 've seen – and heard – something else that 's strange, more strange than all the rest!"

"Tell me, quick!" demanded Janet.

"Two nights ago, I sat here by the window. It was too hot to turn on the light, but it was very dark outside. Presently I heard footsteps in the Benedict garden. They were light, quick footsteps, and sounded exactly as if some one were running about, or skipping and jumping. First I thought it must be a big dog, for it could n't possibly have been either one of those two old ladies, running and skipping that way! And then I heard a soft humming, as if some one were singing a tune half under the breath. And then, very soon after, a door opened, and a voice called out, very softly, 'Come in, now!' And after that all was quiet. Now, Janet McNeil, I 'm simply positive there 's some one else in that house beside the two old ladies, – some one who has n't been seen yet. What do you make of it?"

"You must be right," replied Janet, thoughtfully. "It could n't be either of them running about in the garden in the dark and humming a tune. It is n't at all what they 'd be likely to do. I think it must be some one else, more – more human and natural, somehow. And younger, too. But what on earth do they all keep so shut up for, and act as if they were afraid to be seen! It 's the queerest thing I ever heard of. You certainly have moved next door to a 'dark-brown mystery,' Marcia!"

For the ensuing hour the girls embroidered steadily and discussed "Benedict's Folly" and its inmates in all their peculiar phases. But, turn and twist it as they might, they could find no answer to the riddle. After a while, Janet changed the subject.

"By the way, Marcia, how are you coming on with your violin practice? Have you begun taking lessons here yet? You know that was one of the principal things you folks moved to the city for, – so that you could study with the best teachers."

"Yes, I 've begun with Professor Hardwick," said Marcia, "and I 've practised quite hard lately. It 's about all I had to do. He says I 've made some progress already."

"Oh, do get your violin and play some for me!" begged Janet. "I 'm just starving for some good music. I have n't heard any since you left Northam."

So Marcia obligingly went to the parlor and brought back her violin. When she had tuned it and tucked it lovingly under her chin, she sat down in the window-seat and ran her bow over the strings in a shower of liquid melody. For one so young she played astonishingly well. Janet listened, breathless, absorbed.

"Marcia dear, you have improved!" she exclaimed, as her chum stopped for a moment. "Now do play my favorite!" Marcia laid her bow on the strings once more, and slipped into the tender reverie of the "Träumerei." But before it was half finished, Janet, wide-eyed with astonishment, laid her hand on Marcia's arm.

"Look!" she breathed. Marcia followed the direction of her gaze, and turned to stare out of the window at the house opposite. And this is what she saw:

The shutter of a window on the top floor had been pushed partly open, and a face looked out, – a face with big, appealing eyes, and a frame of golden, curling hair falling all about it. Straight over at the two in the Window it gazed, eager, absorbed, delighted. And then suddenly, as it detected their own interested stare, it withdrew, and the shutter was softly closed.

The two girls drew a long breath and gazed at each other.

"Janet, – what did I tell you! There is some one else in that house!" cried Marcia.

"I guess you 're right!" admitted Janet, quieter, but no less excited. "But do you realize who that third person is, Marcia Brett? It is n't an old lady; it 's some one just about our own age – it 's a young girl!"

CHAPTER III

THE GATE OPENS

FOR the two ensuing days, Marcia and Janet, tense with excitement, discussed the most recently discovered inmate of "Benedict's Folly," and watched incessantly for another glimpse of the face behind the shutter. How was it, they constantly demanded of each other, that a girl of fourteen or fifteen had come to be shut up in the dreary old place? Was she a prisoner there? Was she a relative, friend, or servant? Was she free to come and go?

To the latter question they unanimously voted "No!" How could she be aught else but a prisoner when she was never seen going in or out, was forced to take her exercise after nightfall in the dark garden, and was kept constantly behind closed shutters? No girl of that age in her right mind could deliberately choose a life like that!

"Do you suppose she has always lived there?" queried Marcia, for the twentieth time. And as Janet could answer it no better than herself, she propounded another question:

"And why do you suppose she opened the shutter and looked out, seeming so delighted, when I played, and then drew in again so quickly when we noticed her? Is she afraid of being seen, too?"

"Evidently," said Janet. "She must be as full of mystery as the rest of them. And yet – I can't, somehow, feel that she is like them; she 's so sweet and young and – oh, you know what I mean!"

Of course she knew, but it did n't help them in the least to solve this latest phase of their mystery. Finally Marcia, who still clung a bit shyly to the fairy lore of her earlier years, declared:

"I believe she 's a regular Cinderella, kept there to do all the hard work of the place by those queer old ladies, and I should n't be a bit surprised if she 's down in the kitchen this minute, cleaning out the ashes of the stove! Come, Jan, let 's go for a walk, and when we come back I 'll play on the violin by the window. Maybe our little Cinderella will peep out again!"

The two girls put on their hats and strolled out for their usual afternoon walk and treat of ice-cream soda. But they had gone no farther from their own door than the length of the Benedict brick wall when they were suddenly brought to a halt in front of the closed gate by hearing a sound on the other side of it. It was a sound indicative of some one's struggling attempt to open it – the click of a key turning and turning in the lock and the futile rattling of the iron knob. And then the sound of a voice murmuring:

"Oh, dear! What shall I do? I can't get this open!"

"Janet," whispered Marcia, "that 's not the voice of Miss Benedict! I know it! I believe it 's Cinderella, and she 's trying to run away! What shall we do – stay here?"

"No," Janet whispered back. "Let 's just stroll on a little way, and then turn back. We can see what happens then without seeming to be watching."

They walked on quickly for a number of yards, and then turned to approach the gate again. Even as they did so they saw it open, and out stepped a little figure.

It was not Miss Benedict! The slim, trim little girlish form was clad in plain dark clothes of a slightly unfamiliar cut. But the face was the one that had appeared in the upper window, and the thick golden curls were surmounted by a black velvet tam-o'-shanter. On her arm she carried a small market-basket, and her eyes had a bewildered, almost frightened, look.

In their excited interest Marcia and Janet had, quite unconsciously, stopped short where they were and waited to see which way their Cinderella would turn. But though they stood so for an appreciable moment, she turned neither way, and only stood, her back to the gate, gazing uncertainly to the right and left. And then, perceiving them, she seemed to take a sudden resolution, and turned to them appealingly.

"Oh, please, could you direct me how to find this?" she asked, holding out a slip of paper. Marcia hurried to her side and read the written address. And when she had read it, she realized that it was the little grocery-shop on the other side of town where she had once encountered Miss Benedict.

"Why, certainly!" she cried. "You walk over five blocks in that direction, then turn to your left and down three. You can't miss it; it 's right next to a shoemaker's place."

The child looked more bewildered than ever, and her eyes strayed to the busy street-crossing near which they stood, crowded with hurrying trucks and automobiles.

"Thank you!" she faltered. "Do I go this way?" And then, with sudden candor, "You see, I 'm strange in these streets." Her voice was clear and pretty, but her accent markedly un-American. Both girls half consciously noted it.

"See here," said Marcia; "would you care to have us take you there? We 're not going in any special direction, and I 've been there before."

An infinitely relieved expression came over the girl's face. "Ch, would you be so kind? I 'm just – just scared to death on these streets!"

They turned to accompany her, one on each side, and piloted her safely across the busy avenue. Then, in the quiet stretch of the next block, they proceeded together in complete and embarrassing silence.

It was a silence that Marcia and Janet had fully expected their companion to break – possibly to reveal some reason for her errand and her strangeness in the streets. They themselves hesitated to say much, for fear of seeming curious or anxious to force her confidence. But she said not a word. The strain at last became too much for Janet.

"I don't blame you for feeling nervous in these city streets," she began. "I 'm a country girl myself, and I act like a scared rabbit whenever I go out alone here." The girl turned to her with a little confiding gesture.

"I 've never been out in them alone before," she said. Then there was another silence during which Marcia and Janet both searched frantically in their minds for something else to say. But it was the girl herself who broke the silence the second time.

"Thank you for your music the other day," she said, turning to Marcia. "I heard you. I often hear you and listen."

"Oh, I 'm so glad you liked it!" cried Marcia. "Do you care for music?"

"I adore it," she replied simply.

"Look here!" exclaimed Marcia, suddenly; "how did you know it was I that played the violin?"

"Because I 've watched you often – through the slats!"

Marcia and Janet exchanged glances. So the watching was not all on their side of the fence! Here was a revelation!

"That last thing you played the other day – will you – will you tell me what it was?" went on their new companion, shyly.

"Why, that was Schumann's 'Träumerei,' " answered Marcia. "I love it, don't you?"

"Yes but I never heard it before; that is, I never remember hearing it, and yet – somehow I seemed to know it. I can't think why. I don't understand. It 's as if I 'd dreamed it, I think."

Marcia and Janet again exchanged glances. What a strange child this was, who talked of having "dreamed" music that was quite familiar to almost every one.

"Perhaps you heard it at a concert," suggested Janet.

"I never went to a concert," she replied, much to their amazement. And then, perceiving their surprise, she added:

"You see, I 've always lived 'way off' in the country, in just a little village – till now."

"Oh – yes," answered Janet, pretending enlightenment, though in truth she and Marcia were more bewildered than ever.

But by this time they had reached the little grocery-shop, and all proceeded inside while their new friend made her purchases. These she read off slowly from a slip of paper, and the grocer packed them in her basket. But when it came to paying for them and making change, she became entangled in a fresh puzzle.

"I think you said these eggs were a shilling?" she ventured to the grocer.

"Shilling – no! I said they were a quarter," he retorted impatiently.

"A quarter?" she queried, and turned questioning eyes to her two friends.

"He means this," said Marcia, picking out a twenty-five-cent piece from the change the girl held.

"Oh, thank you! I don't understand this American money," she explained. And Marcia and Janet added another query to their rapidly growing mental list.

On the way back home, however, she grew silent again, and though the girls chatted back and forth about quite impersonal matters, – the crowded streets, the warm weather, the sights they passed, – she was not to be drawn into the conversation. And the nearer they drew to their destination, the more depressed she appeared to become. At last they reached the gate.

"Shall you be going out again to-morrow?" ventured Marcia. " If so, we will go with you, if you care to have us, till you get used to the streets."

The girl gave her a sudden, pleased glance. "I – I don't know," she said. "You see, Miss Benedict hurt her ankle a day or two ago, and she can't get around much, so – so I 'm doing this for her. If she wants me to go to-morrow, I will. I 'd be so glad to go with you. How shall I let you know?"

"Just hang a white handkerchief to your shutter before you go, and we'll see it. We 'll watch for it!" cried Marcia, inventing the signal on the spur of the moment. And then, impetuously, she added:

"My name is Marcia Brett, and this is Janet McNeil. Won't you tell us yours, if we 're to be friends?"

"I 'm Cecily Marlowe," she answered, "and I 'm so glad to know you." As she spoke she was fumbling with the big key in the lock of the gate, and as the latter swung open, she turned once more to face them, with a little pent-up sob: "I don't know why I 'm here – and I 'm so lonely!" Then, frightened at having revealed so much, she turned quickly away and shut the gate.

As they listened to her footsteps retreating up the path and the closing of the front door Marcia and Janet turned to each other, a thousand questions burning on their tongues. But all they could exclaim in one breath was:

"Did you ever!"

CHAPTER IV

THE BACKWARD GLANCE

THE next twenty-four hours were spent in delightful speculation. So her name was Cecily Marlowe! Was she any relation of Miss Benedict? "Marlowe" and "Benedict" were certainly dissimilar enough.

"But then she might be a relation on Miss Benedict's mother's side," suggested Marcia.

"Does it sound likely when you think what she said just at the last – that she did n't know why she was there?" replied Janet, scornfully. "She could n't be in doubt about it if she were a relation, either come on a visit or there to stay!" Which argument settled that question.

"But where do you suppose she has come from?" marveled Marcia. "She said she 'd always lived in a little country village, and she did n't know a thing about American money. She 's foreign – that 's certain. Even her clothes and her way of speaking show it. But from where?"

"Did you notice that she said 'shilling'?" suggested Janet. "That shows she must be English. She looks English. Now will you tell me how she could get 'way over here from England and not know why she had come?"

"It sounds as if she might have been kidnapped," said Marcia. "Why, Janet! this is precisely like a mystery in a book. Do you realize it? And here we are living right next door to it! It 's too good to be true!"

Janet's mind had, however, gone off on another tack. "I can't understand that remark she made about the music. 'Träumerei' is certainly about as well known as any piece of classic music. She said she never remembered hearing it, and yet it seems somehow familiar to her. Can you make anything out of that?"

Marcia could n't. "Maybe it 's all just a notion," she suggested helplessly. "Suppose I play some on the violin here in our window right now. She seems to enjoy it so. And maybe she 'll open her shutter again."

So they sat on the window-seat, and Marcia played her very best, including the "Träumerei," but no golden head appeared from behind the shutter that afternoon.

"Never mind," said Janet. "We 'll see her to-morrow, most likely. Perhaps she 's busy downstairs now."

"But is n't she the prettiest little thing!" mused Marcia, reminiscently. "The loveliest big blue eyes, and curly golden hair, and such a trusting look in her face, somehow! It went right down to the very bottom of my heart, if it does n't sound silly to put it that way."

"Yes, I know," agreed Janet. "I felt the same way. But does n't it strike you queer that – "

"Oh, the whole thing 's queer!" interrupted Marcia. "The queerest I ever heard of. I guess you agree with me now, Janet, that I had a secret worth talking about in 'Benedict's Folly.' But let 's wait till to-morrow and see what happens."

The morrow came and went, however, and nothing happened at all. Hour after hour the two girls watched for the signal of the white handkerchief, but every shuttered window of the old mansion remained blank. Neither did any one go in or out of the gate. Late in the afternoon Marcia played again at the window, but the sweetest music called forth not a single sign from behind the walls of the house next door. Janet had but one solution to offer.

"They probably did n't need any marketing done to-day, so she naturally did n't go out."

"But why could n't she have at least looked out a moment from her window?" cried Marcia, disconsolately. "Surely that would have been easy to do, when she said she cared so much for the music. She must have known I was playing just for her!"

"She may have been somewhere in the house where she could n't. You can't tell, and ought n't to blame her without knowing," declared Janet, defending the conduct of the mysterious Cecily. "To-morrow we 'll see her again, no doubt."

On the morrow her prophecy was fulfilled. They did see her again, but under circumstances so peculiar that they were quite dumfounded. All the morning they watched and waited in vain for some signal from the upper window. But none came. And the main part of the afternoon passed in precisely the same way. They sat very conspicuously in their own window-seat, so that there could be no doubt in Cecily's mind about their being at home. Marcia even did a little violin practice while they waited. And still there was no sign. Suddenly, about five o'clock, Janet clutched at her chum's arm.

"Look!" she cried.

Marcia looked, and down the path from the front door of the strange house she saw Cecily, dressed to go out, approaching the gate. It was plain that she was bound on another marketing expedition for the basket hung from her arm.

"Well! what do you make of that!" exclaimed Marcia in bewilderment. "Did she signal to us?"

"No, she did n't," returned Janet. "I 've watched every minute. She could n't have forgotten it. But, do you know, there may be some very good reason why she did n't – or could n't – and perhaps she 's hoping we 'll see her, and be on hand outside, anyway, as we promised."

"But she must have seen us sitting in the window," argued Marcia. "She might at least have looked up and waved her hand, or nodded, or smiled – or something!"

Cecily, meanwhile, was fumbling with the lock of the big old gate, which seemed, as on a former occasion, to give her a great deal of trouble.

"Come," cried Janet to Marcia. "We 'll just about have time to catch her if we hurry." And seizing their hats, the girls hastened downstairs. Their front door closed behind them just as Cecily came abreast of them. What happened next was like a blow in the face!

They had started forward, each with a friendly smile, expecting their new companion to meet them in similar fashion. To their

Cecily Marlowe passed them by without a look

amazement, Cecily Marlowe, after the first sudden look into their faces, dropped her eyes, and passed them by without a glance, precisely as if they were utter strangers to her.

Both girls gasped, stared at her departing figure till she turned the corner, and then into each other's faces.

"The ungrateful little thing!" Marcia presently exploded. "If that was n't the 'cut direct,' I 've never seen it before!"

"An unmistakable way of telling us to mind our own business!" even Janet had to admit. "How humiliating! And yet – "

"Yet – what?" demanded Marcia, indignantly. "You 're surely not going to try to excuse such inexcusable conduct as that! I see very plainly what 's happened. She 's thought it over and decided that we were meddlesome and just trying to push an acquaintance with her, and she thinks she 's a little too exclusive for that kind of thing, and the simple remedy was to 'cut us dead'!" Marcia was quite out of breath when she finished this summing up.

"It does look like it," Janet admitted. "But somehow, even yet, I can't feel that she wanted to do it – of her own accord, I mean."

But Marcia could n't see it in that light. They discussed the question hotly, still standing on the front stoop of the apartment. So long, in fact, did they argue it back and forth, turning and twisting the sorry little occurrence, viewing it in every possible light, that before they realized it, Cecily was returning, her errands accomplished. How she had managed to find her way and cross the streets in safety, they could only conjecture.

To reach her own gate, she had to pass directly by where they were standing, and they saw her approaching down the block.

"Here she comes," muttered Marcia. "Now, let 's stand right here and watch her as she goes by. She can't help but see us. We 'll give her one more chance to do the proper thing."

And so they waited, breathless, expectant, while the girl came rapidly on, her eyes cast down, watching the pavement. But even when she was quite in front of them, she did not once look up, and without comment their gaze followed her retreating figure to the gate.

As she fitted the big key and swung the gate open, they were just about to turn to each other in angry impatience when something else happened.

Cecily Marlowe turned her head and looked back at them for one long, tense moment. It was such a wistful, imploring look, a gaze so full of appeal for forgiveness, so plainly in contrast with her recent conduct, that their hearts melted at once.

Simultaneously they waved their hands and smiled at her, and she smiled back in return, the most adorable little smile in the world, full of trust and confidence and utter friendliness.

Then she hurried in and closed the gate, leaving her two new friends outside more bewildered than ever.

CHAPTER V

THE HANDKERCHIEF IN THE WINDOW

THE next day was spent by the two girls in an expedition to one of the near-by ocean beaches with Aunt Minerva. Under ordinary circumstances it was a treat that would have delighted their hearts. But, as matters stood, they only chafed with impatience to be back at their bedroom window, watching the house next door. The date for the trip, however, had been set some time before, and Aunt Minerva would have thought it very strange if they had begged off, for such flimsy reason as they could have offered.

The day after found them again on watch, though what they expected to see they could n't have told. It was plain that, in spite of appearances, Cecily Marlowe's friendly feeling toward them was undiminished. The charming backward smile had indicated that unmistakably. But how to make it fit in with her refusal to signal and her forbidding conduct they could not understand, and the mystery kept them in a constant ferment of surmise.

But even as they sat discussing it next morning, their fancy-work lying unheeded in their laps, they looked out suddenly with a simultaneous gasp of astonishment and delight. There was a tiny white handkerchief attached to the shutter in the upper window and fluttering in the breeze!

"It 's the signal – our signal!" cried Marcia. "Now what shall we do? – show that we 've seen it by waving something? Here 's my red silk scarf."

"No," decided Janet. "Perhaps she 'd rather not have us do anything that might attract attention. Let 's go right down to the street, as we said we would, and see if she 's there."

They lost not a moment's time in reaching their front steps. But there was no sign of Cecily till they had come abreast of the Benedict gate. This they discovered ajar, and two blue eyes peeping out of a narrow crack. As they came in sight, there was a smothered exclamation, "Oh! I 'm so glad!" The gate opened wider, and Cecily stood before them.

"You are so good!" she began at once, in a low voice, stretching out both hands to them. "I was afraid you – you would n't come. I left the signal there almost all day yesterday – "

"We were away!" cried Marcia, promptly. "I 'm so sorry. We went – "

"Oh, then – oh, it 's all right!" breathed Cecily, in relief. "I was sure you were angry at – at the way – I acted."

It was on the tip of Marcia's tongue to demand why she had acted so, but she refrained. And Cecily hurried on:

"I – I just had to signal for you. I – we are in great trouble – and I don't know what to do."

"Oh, what is it?" cried both girls together.

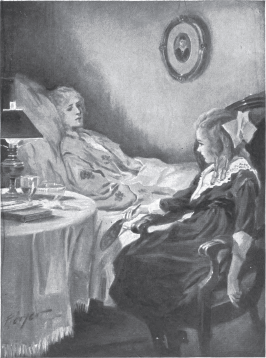

"Miss – Miss Benedict is very ill," she continued hesitatingly. "She – she fell and hurt her ankle the other day, and – it 's been getting worse ever since. She 's in bed – suffering great pain both yesterday and to-day. It 's terribly swelled – "

"But why does n't she send for a doctor?" interrupted Janet, hastily. "She ought to have one if it 's as bad as that."

"I asked her that, too, yesterday, and she only said: 'No, no! I cannot, must not have a doctor, child!' And when I asked what I could do for her, she answered, 'I don't know, I 'm sure!' So there she lies – just suffering. And – and I could n't think of anything else to do, so I signaled to you. You are my only friends – in all this city!"

There was something infinitely pathetic about the way she brought out this last statement. It touched the hearts of both her listeners, and because of it they inwardly forgave her, once and for all, for any action of hers that had offended them. And they had the good sense not to comment on the strangeness of Miss Benedict's behavior.

"Well, if she won't have a doctor, we must think what else there is to be done, began Janet, practically.

"I wish you 'd let me bring Aunt Minerva in to see her," said Marcia. "She hurt her ankle just like that, two years ago, and she 'd know exactly what – "

"Oh, no, no!" cried Cecily, starting forward. "Miss Benedict would not want that – does not want to see any one. Please – please do not even mention to your aunt anything about her – or me! Miss Benedict would not wish it."

The request was certainly very peculiar, but the girls were able to conceal their surprise, great as it was. "Very well," said Marcia, soothingly. "If you 'd rather have it that way, we certainly won't speak of it. But I 've just had another idea. I remember Aunt Minerva had a certain kind of salve that she used for her ankle, and she kept it tightly bandaged on. It did her lots of good – cured her, in fact. Now I believe I could get that salve at a drug-store here – "

"Oh, could you?" exclaimed Cecily, in immense relief. "Let us go at once."

"But you need n't trouble to go," said Marcia. "We won't be ten minutes and will come right back with it."

"I prefer to go," replied Cecily Marlowe, with such an air of quiet finality that neither dared to question it. All three started out, after Cecily had locked the gate, and proceeded to the nearest drug-store. Here Marcia made the purchase, and paid for it from the change in her own hand-bag. But when they were outside the store Cecily turned to her gravely:

"I have a little English money of my own, but I did not like to offer it in the shop. If you will – will tell me how much the salve cost – in shillings – I will give it to you." And she held out several English shillings to Marcia.

"Oh, you need n't do that! I 'm glad to be able to think of something to do for Miss Benedict. It 's such a little matter – "

"Please!" reiterated Cecily. "I wish to tell her I bought it myself."

"Why?" cried Marcia, and then the next moment wished she could recall a question that seemed to border on the personal.

"Because I – I dare not tell her I have – have been talking to you!" hesitated Cecily, in an unusual burst of candor. And after that revelation they all walked back to the gate in an uneasy silence.

When they stood again in front of the blank barrier to the mysterious house, Cecily turned to Marcia.

"I love your music," she said. "I always listen to it whenever you play. I knew you had been playing – just for me – these last few days, and I wanted to look out of my window and – and wave to you, but – I must not. I am always there when you play – listening. I wanted you to know it."

"Oh, I 'm so glad!" cried Marcia, delightedly. "I hoped it would please you. I 'll play more than ever now. I 'll do all my practising there, too."

"Cecily," said Janet, abruptly, venturing on personal ground for the first time, "you are very lonely there, in that big house, with no other young folks, are n't you?"

"Yes," answered Cecily, speaking very low, and glancing in an uncertain way at the gate.

"Well, why don't you ask – er – Miss Benedict, if you could n't run in and visit us once in a while, or go out for a walk with us sometimes? Surely she would n't object to that."

"Oh, no, no!" cried Cecily, hastily. "I 'd – oh, how I 'd love to, but – but – it would n't do, – it would n't be allowed! No, I must not." There was nothing more to be said.

"At least, then," added Marcia, "you 'll let us know if you need anything else – you 'll signal to us?"

"Yes," said Cecily, "I 'll do that." She got out the key, and unlocked the gate. Then she faced them with a sudden, passionate sob.

"You are so wonderfully good to me! I love you – both! You 're all I have to – care for!"

Then the gate was shut, and they heard her footsteps fleeing up the pathway.

CHAPTER VI

CECILY REVEALS HERSELF

THAT night the two girls held a council of war.

"It 's perfectly plain to me," said Marcia, "that that poor little thing is right under Miss Benedict's thumb. I think the way she 's treated is scandalous – not allowed to go out, or speak to, or associate with, any one! And scared out of her wits all the time, evidently. What on earth is she there for, anyhow?"

Janet scorned to reply to the old, unanswerable question. Instead she remarked:

"She 's breaking her heart about it, too. I can see that. And, Marcia, was n't it strange – what she said just at the last – that she loved us, and that we were all she had to care for! Where can all her relatives and family be? Miss Benedict certainly can't be a relative, for Cecily calls her 'Miss.' To think of that lovely little thing without a soul to care for her – except ourselves. Why, Marcia, it 's – it 's amazing! But the main question now is what are we going to do about it? We must help her somehow!"

"I know what I 'm going to do about it," replied Marcia, decisively. "I 'm going to tell Aunt Minerva about it, and see if she can't – "

"Wait a minute," Janet reminded her. "You forget that Cecily fairly begged us not to mention anything about her to any one."

"That 's so," said Marcia, looking blank. "What are we going to do then?"

"There 's only one thing I can think of," answered Janet, slowly. "Miss Benedict may forbid Cecily to meet or speak to us, but she can't forbid us meeting and speaking to Cecily, can she? So why can't we just watch for Cecily to come out, and then go and join her? She can't stop us – she can't help herself; and between you and me, I think she 'll be only too delighted!"

"Good enough!" laughed Marcia. "But what an ogre that Miss Benedict must be! I 'm horribly disappointed about her. After I heard her speak that time I was sure she must be lovely. It does n't seem possible that any one with such a wonderful, sympathetic voice could be so – so downright hateful to a dear little thing like Cecily."

"I must say it seems just horrid!" cried Janet, vehemently.

That night, after darkness had fallen, the two girls, settling themselves without a light at their open window, heard, as Marcia had once before described, the sound of running feet in the garden beyond the wall. This time there was no doubt in their minds about it. It was certainly Cecily, taking a little exercise, probably on the deserted path.

"I wonder why she runs," marveled Marcia. "I should n't feel like running around there all by myself."

"I think I can understand, though," added Janet. "She 's cooped up all day in that dreary old place, and probably has to keep awfully quiet. I 'd go crazy if I were shut in like that. I 'd feel like – like jumping hurdles when I got out of doors. And she 's a country girl, too, remember. Get your violin, Marcia, and play something. I know it will comfort her to know we 're near by and thinking of her."

So Marcia brought her violin, and out into the darkness of the night floated the dreamy, tender melody of the "Träumerei." The romance of the situation appealed to her, and she played it as she never had before.

At the first notes the running footsteps ceased, and there was silence in the garden. When the music ended, they thought they could distinguish a soft little sound, half sigh, half sob, from the velvet blackness below; but they could not be sure. And a little later came the click of a closing door.

Marcia put down her violin. "The lonely, lonely little thing!" she exclaimed, half under her breath.

For two days thereafter they maintained a constant, but fruitless, vigil over "Benedict's Folly." Cecily did not appear, either at her window or on a marketing expedition. Neither was there any sound of her footsteps in the garden at night.

The girls began to worry. Could it be that Miss Benedict had discovered the truth about the remedy for her sprained ankle and had, perhaps, shut Cecily up in close confinement, or even sent her away altogether? They were by this time at a loss as to just what to think of that mysterious lady.

On the third afternoon, however, to their intense relief, they saw Cecily emerge from the house and walk toward the gate, with the market-basket on her arm. It took them just about a minute and a half to reach the street.

Cecily came abreast of their own door-step in due time, her eyes cast down as usual; but they were waiting in the vestibule, and she did not see them.

She was well in advance, but still in sight, when they came down the steps and strolled in the same direction. It was not till they had turned the corner that they raced after her, and at last, breathless, caught up with her.

"Oh!" she exclaimed, with a little start; "I – I did not expect to see you to-day. I – you must n't come with me!" In spite of her words, however, it was evident that she was really delighted by their unexpected appearance.

"Look here, Cecily," began Marcia, "why can't we join you when you go to market or are doing your errands?"

"Oh, that would be lovely!" answered Cecily – "only Miss Benedict usually asks me when I come in whether I have met or spoken to any one, and – I can't tell what is n't true!"

Here was a poser! The girls looked crestfallen.

"No – you can't, of course," hesitated Janet.

"And besides that," went on Cecily, "this is the last time I shall go, anyhow, because she 's very much better now, – the salve helped her ankle very much, – and she says she 's going out herself after this. I don't expect to get out again."

There was a moment of horrified silence after this blow. Then Janet, no longer able to endure the bewilderment, burst out:

"Cecily dear, please forgive us if we seem to be prying into your affairs. It 's only because we think so much of you. But who is Miss Benedict, and what is she to you?"

"I don't know!" said Cecily slowly.

"You don't know!" they gasped in chorus.

"No, I really don't. It must seem very strange to you, and it does to me. Miss Benedict is a perfect stranger to me, and no relation, so far as I know. I never saw or heard of her before I came here."

"But why are you here then?" demanded Marcia.

"I – don't know. It 's all a mystery to me. But I 'm so lonely I 've cried myself to sleep many a night."

"Won't you tell us all about it?" begged Marcia. "We 're your friends, Cecily, – you say the only ones you have, – and we don't ask just out of curiosity, but because we 're interested in you, and – and love you."

"Well, I will then," agreed the girl, as they walked along. "I 'll just tell you how it all happened. Ever since I can remember anything, I 've lived in Cranby, a little village in England. Mother and I lived there together. We never went anywhere, not even up to London, because she was never very strong. Father was dead; he died when I was a tiny baby, she told me. We just had a happy, quiet life together, we two.

"Well, about the beginning of this year, Mother was suddenly taken very, very ill. I don't know what was the matter, but I hardly had time to call in a neighbor and then bring the doctor." Cecily paused and choked down a rising sob.

"She – she just slipped away before we knew it," she went on, very low. Marcia pressed her hand in wordless sympathy. Presently Cecily continued:

"Afterward, the neighbor, Mrs. Waddington, told me that while I was fetching the doctor Mother had begged her to see that, if she did n't recover, I should be taken over to New York, and left with a family named Benedict, and she had Mrs. Waddington write down the address. But just then Mother grew so much worse that she could n't explain why I was to be taken there, or what they were to me or I to them. After it was all over we searched everywhere, hoping to find some papers or letters or something that would tell, but we found nothing. So Mrs. Waddington kept me with her for two or three months. Then a friend of hers, a Mrs. Bidwell, was going to the States, and it was arranged that I should go in her care. About two weeks before we sailed Mrs. Bidwell wrote to the Benedict family, saying she was bringing me to New York.

"So we sailed from Liverpool, and the very day we landed, Mrs. Bidwell brought me here. We rang the old bell at the gate, and then waited and waited. I thought no one would ever come. But at last the gate opened, and Miss Benedict stood there in her hat and veil.

"She acted very strangely from the first. Mrs. Bidwell told her all about me, and she never said a single word, but only shook her head several times. I thought she was certainly going to refuse to take me in, her manner was so odd. After she had stood thinking a long time she suddenly said to me, 'Come, then!' and to Mrs. Bidwell, 'I thank you!' And she led me inside, followed by the driver with my box, and shut the gate." Cecily stopped short, as if that were the end of the story.

"Oh, but – go on!" stammered Marcia, quivering with impatience.

"But I must do my marketing now," said Cecily. "Here we are at the shop. I 'll tell you the rest when we come out."

CHAPTER VII

SURPRISES ALL AROUND

"HOW long have you been in New York?" began Janet, when at last they emerged from the little shop.

"About two months," said Cecily. "And I 've lived in that place all this time, and have not known why. Miss Benedict has never explained. She acts toward me as if I were a lodger, or – or some one she allowed to stay there for reasons of her own, but did n't particularly want to have about. She 's kind to me, but never – friendly. Sometimes she looks at me in the strangest way – I can't imagine what she 's thinking about. But why does she live like this?" and she turned inquiring eyes on the girls.

"I 'm sure we don't know!" exclaimed Marcia. "We only wonder about it. The house seems to be all shut up."

"Why, it is!" Cecily enlightened them. "And it makes it so dark and gloomy! There is lovely furniture in the drawing-room, but it is all covered over with some brown stuff – even the pictures. And most of the other rooms are not used at all – nothing on the ground floor. I eat down in the basement, and my bedroom is on the top floor – where I looked out that time. I have never been in any of the other bedrooms except Miss' Benedict's, when her ankle was bad."

"But what do you do with yourself all day?" asked Janet.

"I keep my room in order, and help Miss Benedict whenever she lets me. Of course, she prepares all the food herself, but in such a pretty, dainty way. But there are a good many hours when the time hangs so heavy on my hands. Sometimes she lets me dust the rooms on the ground floor. She keeps everything very, very neat, even if it is all covered up and never used. The rest of the time I sit in my room and read the few books I brought with me, and tell myself long stories, or listen to your music. I dare not now even peep through the shutters. Once I opened them, when you were playing, but Miss Benedict came in just then and forbade me to do it again."

"Does n't she ever let you go out and take a walk or get a little exercise?" questioned Marcia.

"No, the only times I have gone out have been just lately, when her ankle has been so bad. At night, after it is dark, she lets me run about the garden a bit, but never in the daytime."

"But how did she find out about your knowing us?" broke in Janet.

"Why, of course I told her – that first time after you were so good to me – all about meeting you, and how lovely you were to me. I thought she 'd be so glad I 'd found such nice friends. But she looked so queer – almost frightened, and she said: 'You must not speak to them again. It was kind of them to help you, but you must not encourage them in any way. Remember, child!' And I was only trying to obey her when I passed you without looking up the second time I went out."

"Cecily," said Marcia, suddenly, "what does Miss Benedict look like, anyhow? Do you ever see her without that veil? Is n't she very old and plain?"

"Why, no," answered Cecily, simply. "She 's very beautiful."

"What!" they gasped in chorus.

"Yes, I was surprised too, that day I came. After the driver had brought my box into the hall (she would n't let him take it any farther), and she had shut the door behind him and we were left alone, she seemed to – to hesitate, but at last she raised her hands and took off her bonnet and veil. I don't know what I expected, but I was surprised to see such a lovely face. Her hair is gray, almost white, and so soft and wavy. And yet she has rosy cheeks, and white teeth, and the most beautiful big gray eyes. And her voice is very sweet, too. Do you know, I believe if she 'd only let me, I could just love her, but she holds me off as if she were somehow afraid of me. It 's all very strange."

The girls were completely nonplussed by this latest bit of information, and found it hard to couple Cecily's attractive picture with the little black-robed and veiled figure that they knew as Miss Benedict. The voice alone tallied, and Marcia recounted how she had once met Miss Benedict in the little grocery-shop. Suddenly, however, she was struck by a new thought, and demanded:

"But how about the other one?"

Cecily opened her eyes wide. "Other one?" she queried. "Oh, you mean the other person in the house?"

"Why, yes," said Marcia. "The other old lady who sits in the room on the second floor."

"Oh, is it an old lady?" inquired Cecily, in surprise.

"Why, of course! Did n't you know it?" exclaimed Marcia.

"I knew there was some one in there – some invalid. For Miss Benedict has always warned me to be very quiet in going by that door, because some one was ill in there. But she never told me who it was, nor anything more about her. She always waits on her herself. Even when her ankle was hurting her so, she would drag herself out of bed many times a day to go into that room. But tell me, how did you know there was an old lady in there?"

Then Marcia recounted what she had seen on the night the wind tore open the shutter. "How strange this all is," she ended, "that Miss Benedict should never tell you who this person is! Why do you suppose she is keeping it a secret?"

As this was a problem none of them could solve, they could only conjecture vainly about it as they walked along. But by this time they had approached within a block of the house itself, and before they turned the corner once more they all unconsciously halted.

"Cecily," said Marcia, suddenly inspired with a bright idea. "I have the grandest scheme! If Miss Benedict is going to do the marketing after this, perhaps we won't see you again for some time. But I 've a plan by which we can hear from each other as often as we like. You take a walk in the garden every night, don't you?"

"No, not always," answered Cecily. "Miss Benedict allows me to, but often I don't care to. It 's so dark and – and lonesome."

"Well, after this, be sure to go out every night. Our window, you know, is directly over the garden wall, only three stories up. I 'm going to have a long string with a weight attached to it, and fasten it in the window. Every night, after dark, we 'll write a note to you, fasten it to the string, and drop it down into the garden among the bushes. You can find it in the dark by feeling for the string, and if you have one written to us, you can fasten it on, and we 'll pull it up. Is n't that a dandy idea?"

Cecily's eyes sparkled for a moment, but suddenly her face clouded. "Oh, it – it would be glorious!" she murmured. "Only – I must not. Even if Miss Benedict does n't know about it, I know she would forbid it if she did. So – it would be wrong for me to do it!"

"Oh, Cecily! why should you care?" cried Marcia, impatiently. "And why should she object to three girls sending little notes to one another? It would be cruel to forbid that. It is n't really wrong, you know."

"But she is n't cruel to me," Cecily interrupted. "You must n't think that. She – well, somehow, I feel she would be nice to me, only something is holding her back. She is n't a bit cruel. I sometimes feel as if I could care for her in spite of everything. So I don't want to go against her wishes."

"Well, then," began Janet, "here 's a way out of it. We will write to you anyway. Miss Benedict can't forbid us to do that, and you need n't answer at all – need n't even read them, if you don't want to. But we 'll write, nevertheless, and you can't prevent it!"

When Cecily smiled, her face lit up as if touched by a shaft of sunlight. And she smiled now.

"I don't believe I ought to read them," she said; "but, oh! it would keep me from being so very lonely. But I must be going back now. I 've been longer than usual. Good-by!"

Cecily was still smiling as she turned away, while Janet and Marcia stood looking after her, waving farewell to her as she rounded the corner.

CHAPTER VIII

AT THE END OF THE STRING

IT was past midnight, that night, before the two girls could settle themselves for a wink of sleep. So bewildering had been Cecily's revelations about herself and Miss Benedict and the conditions in the mysterious house, that they found inexhaustible food for discussion and conjecture.

The most interesting question, of course, was the absorbing mystery of how Cecily came to be there at all.

"Why should her mother have sent her there?" demanded Marcia, for the twentieth time.

"Perhaps she was a relative," ventured Janet.

"That 's perfect nonsense," argued Marcia, "for then Miss Benedict would surely have acted quiet differently. If she had been the most distant connection, Miss Benedict would surely have told her. No, I should say she might be the child of a friend that Miss Benedict never cared particularly about, and yet she does n't quite like to send her away. Is n't it a puzzle? But what do you think of Miss Benedict being beautiful! I can't imagine it!"

"And then, too, think of Cecily's not knowing there was another old lady in the house!" added Janet.

"What a darling Cecily is!" exclaimed Marcia, irrelevantly. "If Miss Benedict knew how sweet and loyal and obedient Cecily is, she 'd be a little less strict with her, I 'm sure. I suppose she does n't want her to gossip about what goes on in that queer house. And, by the way, we must get our string in working order to-morrow. Let 's send her other things beside notes, too – things she 'd enjoy."

And until they fell asleep they planned the campaign for lightening the lonely hours of the girl next door.

Next day they jointly wrote a long letter, – telling all about themselves, their homes, their

They heard Cecily's light footsteps

schools, their studies, and any other items they thought might interest her, – fastened it to the end of the string, and dropped it into the dark garden after nightfall. Later they heard Cecily's light footsteps in the gloom below, and when they pulled up the string just before they went to bed, the note was gone.

"Well, she 's evidently decided that it would be all right for her to take it," said Janet; "and I 'm relieved, even if she does n't answer. I can see why she might n't think it right to do that. And now we must plan to send her something besides, every once in a while. I should think she 'd just die of lonesomeness in that old place, and with hardly a thing to do, either!"

That night they sent her down a little box of fudge that they had made in the afternoon, and the next night a book that had captivated them both. And when they pulled up the string the evening after, there was the book again, and in it a tiny note, which ran:

DEAR GIRLS: You are too, too good to me. I ought not to be writing this. It is wrong, I fear, but I just cannot sleep until I have thanked you for the sweets, and this beautiful book. I read it all, to-day. You are making me very happy. I love you both.

CECILY.

Meantime, they had seen Miss Benedict go in and out once or twice, limping slightly, and had watched her veiled figure with absorbed interest.

"Who could possibly imagine her as beautiful!" they marveled. And truly, it was an effort of imagination to connect beauty with the queer, oddly arrayed little figure. Also, at various times during each day, Marcia made a point of giving a little violin concert at her window, and, at Janet's suggestion, had chosen the liveliest and most cheerful music in her repertoire for sad little Cecily's entertainment.

The two girls likewise exhausted every possibility in the line of small gifts and tiny trifles to amuse and entertain their young neighbor. But there was no further communication from her till one night after they had sent down an embroidery ring and silks, the latest pattern of a dainty boudoir-cap, and elaborate instructions how to embroider it. Next night there was a note on the end of the string when they drew it up. It read:

How dear of you to send me this! I love to embroider, and had brought no materials with me. And now I want to ask you a question. Do you mind what I do with it after it is finished? Is it my very own? What can I ever do to repay you for all your kindness!

In their answer they assured her that she could make any use of the boudoir-cap that pleased her. And then they spent much time wondering what use she was going to make of it.

Two nights later, when they pulled up the string, they found, to their surprise, a small parcel attached to the end. It contained a little box in which lay, wrapped in jeweler's cotton, a tiny coral pendant in an old-fashioned gold setting, and a silver bracelet of thin filigree-work. The pendant was labeled, "For Marcia, with Cecily's love," and the bracelet, "For Janet, with love from Cecily."

The two girls gazed at the pathetic little gifts and sudden tears came into their eyes.

"Oh, Jan!" half sobbed Marcia; "we ought n't to keep them! They 're probably the only trinkets she has."

But Janet was wiser. "We must keep them," she decided. "Cecily does n't want all the giving to be on one side, and she has probably been longing to do something for us. I suppose these are the only things she had that would be suitable. Much as I hate to have her deprive herself of them, I know she 'd be terribly hurt if we sent them back. To-morrow we must write her the best letter of thanks we can."

So the days went by for two or three weeks. The girls caught, in all this time, not so much as one glimpse of Cecily, but they managed, thanks to their "line of communication," to keep constantly in touch with her. Meantime, the summer weather waxed hotter and hotter, and the city fairly steamed under the July sun. Their own time was taken up by many diversions: trips to the parks, beaches, and zoo; excursions out of town with Aunt Minerva; shopping, and quiet sewing or reading in their pleasant living-room. Every time they went out of their home on a pleasure-jaunt, they felt guilty, to think of the lonely little prisoner cooped up in the dreary house next door, and both declared they would gladly give up their places to her, had such a thing been possible.

Then, one night, something unusual occured. They had sent down the usual note, and also a little work-basket of Indian-woven sweet-grass, the souvenir of a recent trip to the seaside. To their astonishment, when they drew up the string, both note and basket were still attached. This was the first time such a thing had happened.

"What can be the matter?" queried Marcia. "Can it be possible that Cecily feels she must n't do this any more?"

"I did n't hear any footsteps down there to-night, did you?" said Janet.

"No, come to think of it, I did n't. She must have stayed indoors for the first time since we began this. But what do you suppose is the reason?"

Janet suddenly clutched her friend. "Marcia, can it be possible that Miss Benedict has discovered what we 've been doing, and won't let her come out any more?"

"I believe that 's it!" Marcia's voice was sharp with consternation. "Would n't it be dreadful, if it 's so?" They sat gloomily thinking it over.

"Well, what are we going to do about it?" demanded Marcia.

"Wait till to-morrow night and try again," counseled Janet. "It 's just possible Cecily had a headache or felt sick from this abominable heat and could n't come down. Let 's see what happens to-morrow."

The next night they tied the basket and another note to the string and dropped it down hopefully. But they drew it up untouched, precisely the same as before.

"It 's just one of two things," decided Marcia. "Either Cecily is ill or Miss Benedict has found out about our little plan and forbidden Cecily to go on with it. What are we to do? Keep on sending notes, or stop it? Suppose Miss Benedict herself should find one sometime."