MEMORIALS OF MRS. GILBERT.

CHAPTER I.

HULL.

CONTENTS OF CHAPTER I.

Salome's Marriage—Anxiety for her Sister—A poetic Effusion—Death of the Princess Charlotte—Politics—Summer Days at Ongar—Visit of her Father and Mother—Her eldest boy at Ongar—Letter to Mrs Laurie—Miss Greaves—The Greenland Fishery—Supposed fatal illness of her Father.

CHAPTER I.

HULL.

1817-1820.

|

"But little know they of the toils of thought, Heart, head, and conscience, to the labour brought; The search for truth in Scripture's deepest mine; The snare resisted, not to teach, but shine." |

| ANN GILBERT. |

| "Many an evening by the waters did we watch the stately ships." |

| TENNYSON. |

"EIGHT happy and successful, though truly laborious years" were, as Mrs Gilbert wrote long afterwards, spent by her husband in Hull, as pastor of the large congregation at Fish Street Chapel. During those years six more children were added to the household; and she herself was not less active and laborious in her sphere, and certainly not less happy, than her husband. But in dealing with this, as with other busy periods of her life, it will be necessary to compress the narrative much more than hitherto.

Three weeks after they had entered their new home, her third child, a son, was born.

"He wants nothing but a name," she writes, "which we are quite at a loss about. I should like to call him 'Isaac,' but Mr Gilbert does not like it, and nobody thinks it pretty. Indeed, I cannot deny there is nothing but association in its favour."

Her husband's lively niece Salome was at this time absent for a few months, and an allusion to this in a letter home reveals that with all her interest in the orphan girl, she had proved some check to the happy freedom of domestic intercourse, as the addition of a third in the home of any newly married couple was likely to be.

"The last three months, I believe, we have had more confidential conversation than for three years before; and this is about the only cause of regret to me that Salome is with us. It is almost impossible for three to converse so freely as two, even if all were equally intimate; but I am so persuaded that it is duty to keep her here, and when I look at my own dear children, I feel too so deeply how strong are the claims of an orphan, that if holding up my finger in the dark would remove her, I would not do it. It is a little crook in a happy lot, and I dare not ask to have everything my own way."

This "little crook" did not last long. Richard Cecil, a son of her old friend, and a student at Rotherham College, had now confided to Mr Gilbert his attachment to Salome. Some delay to make up her own mind was all that remained, "and," said his wife, "if I am anything of a conjuror, I can prognosticate the event." Perhaps this prognostication did not require a conjuror. It was soon a settled thing, as we find by the following reference:—

"Salome does not allow that she shall marry for many a year, but if he should be settled soon, I conclude it would not be long, and I cannot help smiling at the little domestic observations which she, unlike her wont, now occasionally makes—of course, quite in a casual way—such as, 'dear, how was this made?' or, 'Was that rabbit's head quite right?' But the smile is quite in my sleeve. Oh, it is a real blessing to have had a little practice in the minutiæ of housekeeping before one is called to perform in the eye of the world, and what is worse, of his wife. When I see the splendid dinners which all the merchants give here, I wonder what I should have done had I settled at —, and in a situation where I must have given, as well as received; for verily in this instance, it is not more blessed to give than to receive."

The "crook" was succeeded by a real anxiety. Allusions presently occur to indications in her sister's health, which after some years ended in her death, the first sorrow of the kind since childhood, that entered this loving family circle. The trial to such a nature was poignant, yet she says—

"I cannot but admire the goodness of God in the many mitigating circumstances with which this affliction is accompanied. How merciful it is that she had not to brood over it during her retirement in Cornwall; that Isaac does not now need her attention; that she is able to feel so much pecuniary ease without continued writing; and that her own mind should have been so previously strengthened and girded for the trial."

In bearing this trouble, too, the elder sister, however prone to dwell in imagination upon dark possibilities, was helped by a characteristic energy of practical hopefulness. She was unwearied in suggesting and investigating all remedies that came to her knowledge, and always sanguine about them. And, then, there was ever the bright domestic duty at hand.

"This is the first evening for weeks I have been able to sit down alone and at home, and now I am enjoying myself. The house is got nicely in order at last; I have just finished a three weeks' wash, and I am every moment expecting Mr Gilbert from Leeds. I have a comfortable parlour, with a neat, brisk fire to greet him, and in the kitchen a little chicken roasting for his supper, added to which all the three children are quiet and in bed."

It may have been observed that, in all her references to her husband, he is termed "Mr Gilbert" or "Mr G." This formal style, which continued almost to the last, was, it need hardly be said, no indication of coldness, but took its rise from early shyness at any exhibition of affection before Salome's sarcastic glances; a proof that the constraint of which she speaks existed in no small degree. The deep and tender devotion of her heart was poured forth whenever it was confided to the pen. His absences, on ministerial duties among the Yorkshire churches, were now very frequent. During one of them she writes:—

"If we look round at other families, we may easily persuade ourselves that ours are light afflictions, dealt out with a sparing and tender hand. If we may be still indulged in this respect, I shall enjoy the thought of your finding a little more rest at home than for a long time you could have had there. There is no thought more delightful to me than that of making your fireside both rest and recreation. It grieves me to think that, with family cares, you should ever find it otherwise, but sometimes you know I am lawfully too tired for the latter. Ah! if I could but plead that at others, I was lawfully too cross for the former, I should have less reason to say, forgive me! . . . I have attended to your study plants with a direct and affectionate reference to their owner,—also with no disrespectful feeling towards themselves."

In the midst of incessant occupation, her pen, if used at all, was devoted to thoroughly homely matters of correspondence, but the receipt of a poetic effusion of her husband's and a breath of country air at the little village of Welton, where she had taken lodgings for her children, seem to have revived the old inspiration. She writes,—

"January 19, 1818.—Why describe the loveliness of one still the idol of your fancy, but whose slightest outline I dare not appropriate? Was it to make me jealous? If I can help it, it shall only make me emulous. But, however, if you had any ill design, I have meditated a sort of revenge in sending you, on the following page, the praises of my first love,—of one who still holds a wide empire in my heart. On receiving your beautiful, inappropriate verses, I longed very much for leisure to reply in kind; but when yesterday, in my solitary ride from Welton, the spirit came over me, it did not flow in that direction. I found my mind carried out towards another object, so I did not check its flight, but gave myself up without reserve to the passing impression. If you can, love it for my sake, as I must endeavour to gaze on the beauties of your mistress for yours, and if I can grow more like the charming original I will. But remember there will always be a painful difference between the seen and the unseen. The visible Helen, I will venture to say, was not so enchanting as the invisible personification which poetry has given to her loveliness. The 'seen,' in this case, is mere mortal clay, drest in a cap and gown; and though I am not intimating that, if you did not see me, and did but know it, I am a Helen, or even a distant relation of that lady, yet I would meet the dis- appointment half way, and assist you to remember that material substance cannot—do what it will, or be what it may—possess the poetic attraction of ethereal essence.

"O beautiful nature, how lovely thou art

In thy bonnet of blue and thy mantle of green!

Love, early and pure, it was thine to impart,

My bosom's soft soother, my fancy's fair queen!

Does life seem a labour, perchance for a while,

Its promise a cheat, by no pleasure repaid?

One glance of thine eye, and one glimpse of thy smile,

Rekindle its brightness, thou beautiful maid! *. . . . . .

"But now for news from that homely scene, where your muse takes her rest with resigned cheerfulness—that good red brick messuage known by the name of No. 8, Nile Street, Hull. . . . The house is now perfect neatness and order; silence and solitude reign throughout (all the children away in the country), interrupted only by the occasional singing of the mangle, or the swing of the oven door; if you would but add the postman's ring, it would be all the music I wish for."

In November 1817, came the shock of the Princess Charlotte's death.

"O," she says to her sister, "this mournful mourning! Before I begin with anything else, I cannot help expressing my interest and grief in the event which has clothed us all in the garments of genuine sorrow. Night and day it has scarcely been out of my thoughts, so deeply melancholy is every view we can take of it; and I confess, though I feel for the public, it is the private part of the story that affects me most. realise every aggravating particular till I can hardly bear to think of it. How it enhances the mercies of our own firesides! I look at dear little H— now as a double favour."

The general grief on the day of the funeral called forth a sermon from every pulpit, that by Robert Hall achieving a wide celebrity. Mr Gilbert chose for his text Jer. xxii. 29, "O earth, earth, earth, hear the word of the Lord!"

"Read it," she says, in writing home, "but be sure you do not look at the following verse! ('Write ye this man childless, a man that shall not prosper in his days,' &c.) It was deeply affecting; the place crowded, the pulpit hung with black, and every eye in tears. O it was most mournful, in the quiet moonlight of that melancholy night, to hear the dumb peals from the churches, chiming till past twelve; and to think that the same sad music was sweeping over the whole land from north to south. We went in the evening to one of the churches, and during the performance on a fine organ of the 'Dead March in Saul,' I gave myself up to the full power of imagination, and I saw the scene then passing in the Chapel Royal like reality."

A lively interest in public events always distinguished her; and she warmly embraced the cause of "the Queen," which became so curiously mixed up with political feeling. At a later period, when "the Manchester Massacre," a charge of Yeomanry upon the people, was in all mouths, she writes,—

"We were at a large party last week, and got so deep into Manchester politics that we were obliged to conclude with a chorus of 'God save the King' called for by the Low party. What do you think of the signs of the times? Mr Gilbert can hardly rest in his bed for interest and anxiety. He is afraid there are fetters forging for his children. I heard there a neat characteristic story of Mr Parsons of Leeds.* He was at a dinner where a very high Tory gave 'Church and King,' supposing Mr Parsons would not drink it. Mr P. drank it, however, very cheerfully; but when his turn came proposed the 'Queen and the Dissenters.' Did you see a reply of Hunt's as he passed in procession through Manchester?—you know, perhaps, that he is separated from his wife—a man as he passed called out—'Hunt, who sent away his wife?'—'The Prince Regent,' my man, 'but hush, we don't talk about that, you know.'"

With the first Spring time in Hull came longings that the dear ones at Ongar might see something of her new home,—nay, if possible, the father and mother, who had never taken so long a journey in their lives, and to whom there was now the special obstacle opposed, of that six miles of water between Barton and Hull, to be traversed only in a precarious sailing boat, for, as yet, no paddle-wheel beat the surface of the Humber. So early as January 1818 she introduces the subject—

"I make one enquiry with all imaginable earnestness. Is it possible that my dear father and mother could visit Hull this year? The journey from London to Barton is about from evening to evening, fare £2, 16s.; and if you were to see the Barton packets coming in every day, as we do, you would begin to think the danger small. There has never been one lost since the days of Andrew Marvell, whose father perished in a very stormy passage; but when the weather is so rough as to be dangerous, they do not sail. The coach passengers always rest at Barton the night, and cross in the morning. When the wind is favourable the passage is made in half-an-hour, and the vessel, though called a boat, is a sloop with mast and deck. Now do, my dear parents, try and think that you will come in the course of the-summer."

The same letter notices her father's recently published, and perhaps in its day, best known work, "Self-Cultivation."

"It appeared to us to make a great improvement in style about the middle of the third chapter, and several parts, especially some chaste but striking figures, we have marked with pencil notes of admiration:—that of the 'echoes among the mountains' is extremely beautiful.* But I do not mention the figures because we think them the best parts either, the whole stream of thought is excellent, and as far as books,—poor quiet books, are ever likely really to improve that stubborn material human nature, I should say that it must be useful."

Of course, her mother, timid with all her courage, was quick enough to see her advantage in the Andrew Marvell accident. "I foresaw," says her daughter, "your ill use of Andrew Marvell, and therefore added what you seem to have overlooked, that when it is so rough as to be dangerous, the boats do not sail." The pleasant thought was not to be fulfilled that year, but in its stead there came the happy prospect of a visit to that dear Ongar, to think only of which, in its rural peace, was she said, "a constant rest to her spirit." Yet there was always now a secret anxiety.

"It grieves me," she says, in writing to her sister, "that you should be obliged to carry daily in your mind even a 'bearable anxiety,' but in this world we shall have tribulation, and it were vain, and perhaps foolish, to wish to evade the universal sentence, either in our own persons, or in those that are dear to us; and soon, even at the longest, the trials we have passed through will appear indeed unworthy to be remembered, but for the peaceable fruit they shall have produced. Oh, woe to those who suffer under barren sorrows!—who get no nearer heaven by the rendings and wounds that detach them from earth."

April 17, 1818.—"Here I am in the study. It is a beautiful afternoon, the wind is blowing the Humber into foam; a number of little vessels are labouring down the stream; the pretty gardens all round us are just coming into bud, and the only green field we can see is looking like spring on a holiday, Oh, how I wish, not that you were just coming over, as I often do, but that you had just got safely in, and were admiring the beautiful prospect now before me! But alas! alas! when and where are we to meet again? If it were possible for father, mother, and Jemima!—but I am afraid you will think me teasing."

The visit of her parents was not yet to be, but the happy day came instead, when she and her husband and child set off for Ongar. It is amusing to contrast the journey with one by the Great Northern Express of these days: how, leaving Hull at four in the afternoon, on May 4, they supped at Lincoln, breakfasted at Peterboro, dined at Baldock, and got into London at half-past ten at night! A few days later they went down to Ongar, and thence she and her husband, and her sister Jane made a delightful four days' excursion to Colchester, driving all the way, and sleeping on the road, both going and returning. It was the first visit to those loved scenes,—The High woods, Mile End, Lexden springs, the Balkerne hill—since the whole family drove away from Colchester nearly seven years before.

At Ongar, in the old house a mile away in the fields, her diary and letters show how happily and characteristically the days passed,—the walks and talks in the well known lanes and meadows, and teas on the grass plot, or in the vine-covered porch; the visits of her brothers Isaac and Martin, coming down to supper on Saturday night, and off on the Monday morning; even her uncle Charles, the "learned" editor, who always treated her father as decidedly the younger brother, driving down in a post-chaise one Sunday. She records her father's preachings in the neighbouring hamlets; her mother's birthday (sixty-one), with its little festival; the family work going on;—"mother with a tale completely written, the production of three weeks' mental fever; father just in receipt of £70 for another book." And then, after five weeks' stay, the sorrowful departure, though with the happiness of taking her youngest sister, Jemima, back with her to Hull. An extract or two from letters to her husband, who had returned to Hull before her, may be permitted.

"Ongar, June 12, 1818.— . . . When will you remember that in order to enjoy a complete sympathy with those I love I like to know the exact times at which anything interesting befalls them? On Wednesday evening, when I believed you would be leaving London, I thought of you incessantly, and spoke the same full often enough; we were drinking tea under the pear tree on the front grass plot, and should have enjoyed ourselves completely, but for the oft-repeated wish that you were with us, and for the recollection that instead of enjoying that Italian sky and balmy air, and beautiful country, you were sitting to be tarred and feathered with heat and dust on a stage coach. On Sunday we expect Martin, and then, if all should be well, we shall once more assemble an entire family at our father's table, and with one pretty sample of a third generation; how I wish that you and the two dear children at home could complete the circle! but let us hope we all may meet one day in a higher house and a fuller company! . . . Dear little J. is much engaged in watching the gardener, and the carpenter, and the bricklayer who has been paving the Hermitage in the shrubbery; and "Master Wood," who has been clearing out the pond; and the sheep-shearers, who have been busy in the farm-yard. I hope he will return to Hull rich in health and knowledge. I am also quite well myself, only half baked and half broiled with incessant sunshine; but I have had two falls, one down the stony declivity towards the pump in the kitchen, and the other down stairs with Jane's beautiful desk in my hand, which fell on its face, and bears my signature at every corner, which I am very sorry for. I am quite unhurt, except a few picturesque bruises. Isaac came on Tuesday, and has begun my portrait. Your likeness I think perfect of the kind, but you know it is the wrong side, and has the wrong expression. It is like you when you wish to be pleasant, but wish still more that you need not be.

. . . The thought of Nile Street and the spring-tide of comforts I have there, is so sweet, that sometimes I feel in a strait betwixt two; yet the thought of leaving this dear peaceful, beautiful spot, with all its living interests, is almost more than I dare indulge,—how impossible it will be to take one more look when I have once turned the corner of the road! But then Hull and all that is dear to me there, will rise like a sun over the distance."

She returned home on the 27th of June in a brisk gale, which she inadvertently admitted laid the vessel "gunwale to." The young Jemima was a bright addition to the household. "Ah," said one of their Hull friends, "I have seen your sister, I have seen the lady that is famous;" "Yes," she replied, "and now, Sir, you see the lady that is not famous."

Her husband's health gave way under his laborious duties, and the unhealthy atmosphere of Hull. Her children (she had eight of them about her before she left Nile Street) and her servants, were continually suffering from illness; visitors were incessantly coming and going, and if any of them were needy or troubled, their stay was only the more prolonged in the hospitable home. In the societies and charities of a large town she took her part; but a brave spirit and unflagging energy bore her through it all; only when anxiety for dear ones touched her, then for the moment, as she expressed it, she "became weak as water," till faith and hope, those "angel helpers," came to her aid.

Her long letters to her family, or to her husband, during the absences which his impaired health now made necessary, are little else than domestic journals, enlivened with little gems of tenderness, or here and there sparkles of fun. A bundle of them in 1818 is chiefly concerned with negotiations for a new arrangement with the publishers of the various works in which herself and her sister were jointly interested. Some difficulty was experienced in obtaining terms, which, under the large sale and increasing popularity of the poems, were considered "just," but that they should be just was her only wish. Characteristically she observes:—

"In order to maintain firm ground, we must ourselves feel convinced that it is reasonable. . . . Martin deems it wise to come forward with 'large and bold demands,' but to our feelings, the path of wisdom, to say nothing of honesty, seems to be somewhat diverse from this. We feel, or fancy, that we can never make a stand to a bold demand till we have ascertained, as well as we can, that it is a just one,—that to use decided language when our own minds hesitate, would be both wrong and foolish; and that the sinking below an extravagant demand (which if it were extravagant must be done), would place us in a more humble situation than the most scrupulous care betrayed to them, lest in the first instance we should ask too much."

Her sister Jemima left Hull for the long journey home on the 30th of March 1819, threatening "to cry all the way to Lincoln, six and thirty miles." Writing to her afterwards, she says,—

"On Friday, while some people were drinking tea with us, I indulged myself with a few minutes' coze with my eyes shut, in order to realise your arrival at Ongar,—hoping to join your circle as well as a separate spirit can. Is father at work on Boydell yet? How we admire Isaac's article on Madame de Stael! he has a magical use of words that gives the beauty and expressiveness of a new language."

But this year was made a very happy one by its fulfilling the great wish of her heart, a visit from her father and mother. Her father, who had suffered latterly from repeated attacks of illness, had been recommended to try sea air and bathing, and the opportunity was taken for the whole family to remove to Hornsea. She herself, too, was very unwell, and though suffering plainly from exhaustion, had, according to the practice of the day, been frequently cupped till the symptoms became alarming. On the 11th of August, avoiding the possible fate of Andrew Marvell by travelling through Doncaster, her father and mother reached Hull. They had timed their journey so as to meet Robert Hall there, and to hear him preach on the Sunday at Fish Street. On the 17th, her brother Isaac's birthday, they all removed to Hornsea, a little fishing village, then so out of the way that letters arrived only three times a week by carrier.

Her mother's penetrating eye and practical good sense soon led her to distrust the effect of the cupping treatment, and low diet, upon so delicate and emaciated a frame. In a shrewd and racy letter home, which gives a glimpse of the life at Hornsea, she says,—

"I remain nearly as sceptical as ever respecting Ann's disorder, notwithstanding ye long list of symptoms with which you were entertained in ye last letter. And I am sure, though I cannot get her to own it yet, that her looks are improved here, and her spirits are better. We all enjoy ourselves very much. You may think of us from ten to one every day walking or riding; and again in afternoon or evening, when the tide is up. I ride on a donkey almost every day, and am become so good a horsewoman as to keep my seat when the animal is sinking in the sand, struggling, and kicking. We have, too, a donkey-cart, which carries the whole party, your father excepted. This all adds to the expense, and extorts from me many a sigh and groan, and I fear when the fun is over, like ye children, I shall cry for my money again: yet we are willing to avail ourselves of such an opportunity, and not to spoil a ship for a halfpenny-worth of tar. Plunging headlong, however, into the sea, does not well suit my nerves. 'Take your time, ma'am,' the women say, when I am clambering up the ladder from the waves, but you can guess how it is, I daresay, as well as if you saw me. Yet I had rather bathe in the sea ten times, than once seethe and roll about on the surface of a warm bath like a bottle! We hope to hear from you now,—no, not every post, but every errand-cart. Let me hear how you all are in plain truth, and no lies. Also how the maid goes on, whether she is gone, or going, and what else is gone, stolen, or strayed.

"On Monday at Hull we are to drink tea at Mrs Carlill's to meet Robert Hall and several more, but all this does not prevent my waking sorely ill this morning."

After some stay in Hull, on leaving Hornsea, her father and mother returned home, taking with them their eldest grandchild, then nearly five years old,—an event to both families, since, with exception of one or two visits home, he remained at Ongar till the death of his grandfather, ten years later.

Her mother became very ill on the journey.

"Little did I think," writes the daughter, "how you, my dear mother, were suffering! How often, during that day, did I wish I could see you for one five minutes; and how distressed I should have been if I had! O, I can hardly believe that the pleasure I have been anticipating and feasting on in many a pleasant reverie, for almost these six years, is gone!—gone so swiftly! How often I think of that dark and dreary morning when I stood crying at the corner of the market place, watching till the coach turned down Silver Street, and the rattle of the wheels died away! I shall never forget it,—nor that pleasant evening when I first caught a glance of the 'Rodney' and dear mother's bonnet, as it drove down the market. These, with the stopping of the chaise at Masbro', with dear Jane and Isaac, are seasons written on my heart.

"If it were possible you could be here when we are quiet, or rather, if we could possibly be quiet when you are here, how glad I should be! I reproach myself now for many things, but I try to put the thought aside. I think I may safely say, that since we have been in Hull, no minister has preached at Fish Street of whom so much has been said by everybody, as of dear father. His praise is, at least, in all this church. I was much pleased to hear that when he rose to speak at the Tract Society, he was clapped up; this is a testimony to general estimation, very different from the rattle of a few sticks at a piece of wit, perhaps hardly worth saying. . . . I thought of you all, on Friday evening at six, very satisfactorily, but was sadly puzzled to decide on which side of the coach Isaac would stand, when he came to meet you at the corner, and whereabouts they would catch the first glimpse of J— ."

Of course the absence now of her eldest child drew forth, from time to time, many a tender thought and word.

"I perceived," she says, "when last at Ongar, that without indulgence, he was yet sensibly injured by being the sole object of attention. This is almost unavoidable, but as far as it can be prevented, I rely upon your joint care. Bless his little heart! How I enjoy the thought of his many privileges and comforts, ghostly and bodily, especially his gardening. . . . Yet I regret very much that there is a portion of his life—a stage of his growth, which I shall never remember; my little boy of five years old, I shall never see, though I may find eventually a better one of six."

Dec. 31, 1819.—"As to dear mother's anxious feeling of responsibility, I wish I could remove it by assuring her how completely my own mind feels at ease respecting him. Not,— O do not suppose it, that I feel any confidence in having him spared to us. I feel rather as if all my comforts were exposed on the brink of a precipice, with a loose and crumbling soil. Disease and accident have keys for every door, and I feel no persuasion that our dear child will not meet with them, even at Ongar."

To Mrs Laurie, Feb. 8, 1820, she writes—

"Whether or not your hands are full, I assure you that mine are; and this alone is the reason that the friends of my youth—they whose names are associated with most that is dear and interesting in that interesting period, are all as nearly forsaken as they can be, while my affections remain faithful to their trust. You ask many particulars relative to my present circumstances, and were I to enter into the detail of my days and weeks, and years, you would believe that my time for correspondence was very small—small enough, pretty nearly, to justify the long intervals I allow in it. . . . I could wish for a little more leisure, or more properly, for a little more time for necessary duty; but far, far, do I prefer this constant pressure to the busy trifling of a life of leisure. I heard a married lady, described, the other day, by a morning caller, as being well, and well dressed, in a well-furnished room, at twelve in the day, sorting seals! O, I felt the privilege of having more work than I can accomplish, compared with the inanity of such occupations! Our dear children, of whom you inquire so kindly and specially, are all (as we think) nice children. . . . Dear J— is altogether a Gilbert; A— is a genuine Taylor—thought a beauty by some, and plain by others; I take a middle opinion. H— is a rough, fat, rosy, honest fellow, with as good-natured a face as ever smiled,—when he is not roaring under some affliction, that makes it look more like a door-knocker, or the lion-faced spout on a church steeple. 'Edward Williams'* improves upon all of us, in one respect, in having beautiful soft curling hair, which his mother turns round her fingers sometimes, with no little pleasure. I think he will be pensive; he is a delicate, elegant, little creature, and wins upon papa amazingly. . . .

"With regard to their dress, it is as plain as can be for many reasons: first, we find it necessary to pursue a strict economy, and think it highly advantageous to them to be educated in similar habits. It always grieves me to see a child with the air of style and fashion about its dress; it seems to be doing it the unkind office of just setting it in at the wide gate, to take its own course on the broad way; besides, it seems to me to spoil the simplicity which should characterise childhood. Secondly, I cannot afford the time, either in work or washing, which would be necessary to keep them in the 'mode,' even if I were to set them in; and thirdly, I am sure that a minister's family rather loses than gains respect, by any assumption of style. You are not to suppose, however, that we distinguish ourselves by an affected and obvious plainness, that would, of itself, attract attention; but I wish my own dress, and that of the children, to be such, that if anyone takes the trouble to cast an investigating look at it, it may be evidently plain, neat, and economical. One thing has long prevented them from looking 'fashionable,' however nicely they might be dressed; I never would suffer the exhibition of their little shoulders, its look of uncomfortableness, and its direct tendency to inure a girl to future exposure, are quite sufficient objections."

Her sense of responsibility in the management of a family and her means of meeting it, are shown in the following extract.

"It is frightful to contemplate the long descent of evil and suffering, resulting from the mistakes, the prejudices, the ignorance, the ill tempers, the want of self-control, the indolence, or the unavoidable hurry of occupation of one individual mother; herself, perhaps, a half-educated girl, and yet entrusted with a freight of incalculable, of eternal value! To such an one, how needful is heart religion, a daily sense of dependence, and yet a cheerful courage, resulting from the assurance that all who lack wisdom, are invited to ask it of God. None can know till they make the experiment, how much of strength and direction for secular duty may be derived from this source. I am myself disposed to believe that nothing which it is right to do, and therefore to do well, is beneath the range, the warrant of prayer. The privilege may be abused by bringing the humbler necessities of life into social prayer, but, between ourselves and Him, to whom the final account must be rendered of work He has given us to do, nothing is mean that requires more wisdom than we have; and in the daily exercise of this emergent communion, 'whoso is wise, and will observe these things, shall see of the loving kindness of the Lord.'"

February 17, 1820—To Ongar.—"I suppose we have all been feeling pretty much alike about the good old King, but I confess that after the death of the Princess I am almost impenetrable. Nothing can be so touching as that, and it is too recent to be forgotten. I try to make the children remember the death of the King, because such an event often supplies a date to the recollections of childhood; but Anne, when I tell her King George is dead, always corrects me with 'George King'—it seems to her that I put the cart before the horse! As we are glad, I suppose you will be glad, to hear that Miss Greaves has just purchased the house next door to us, and has decided upon giving up Greystones. Everybody is pleased to see her settle amongst us, and we are not sorry, I assure you."

The lady here alluded to was a friend at whose hospitable mansion, near Sheffield, they had frequently visited, and it was the value she set upon Mr Gilbert's preaching that induced her to remove to the very inferior situation at Hull. Eventually, by turning two houses into one, and purchasing adjoining gardens, she obtained a roomy and comfortable residence, the delights of which with boundless generosity she threw open to the family of the minister, for whom she had sacrificed so much. The faithful and solicitous friendship of this lady during many years, not only requires grateful acknowledgement, but was too important an element in the happiness of the household with whose fortunes we are concerned, not to receive a passing notice. When the garden ground was purchased, Mrs Gilbert turned her father's garden lore to account, and spent much time in laying it out for her friend; and along those gravel walks the children romped and screamed many a day, always without rebuke from the gentle face that watched them from the window.

A sea-port town offered interests very different from those of the inland places to which the wife, at least, had only been accustomed. A branch of her husband's family had for several generations been connected with the Royal Navy. One member of it, accompanying Captain Cook in his first voyage, gave his name to a group of islands in the Pacific; another, then a midshipman on board, but who afterwards became post captain in the service, was present at Captain Cook's death, and brought home his watch, which, bequeathed to him by the great navigator's widow, remains still as an heirloom. These associations gave Mr Gilbert great interest in the sea, and he himself was always a favourite with sailors. He was concerned in the establishment of a floating chapel at Hull, and once a year the departure of the Greenland whaling fleet gave occasion to a striking service, when Fish Street Chapel was crowded with sailors, and a special sermon was addressed to them. During their absence in the frozen seas, prayer-meetings were held on their behalf at some private houses, at which the minister and his wife were always present; and from the study window, which then commanded a view of the Humber, the returning ice-battered vessels were eagerly watched for. Many of them belonged to friends deeply interested in the results, and news of the number of fish and tons of oil, of this and the other well-known ship in the offing, was brought to the door by hasty footsteps. With yet deeper interest the distant rigging would be searched by the telescope to see whether a coffin suspended from the yard-arm announced a death on board during the voyage. Too often it was so, and the minister departed on a heart-rending errand to some mournful household. For a ship to be reported "clean" might be almost ruin to the owners, and once a famous "captain," whose success was all but unvaried, arrived insane in his cabin from an unusually disappointing season.

Most people of any means in Hull had shares in, if they did not own, a Greenland ship; and Mr Gilbert at one time held a small share, so that for some years his wife's letters to Ongar contain unwonted references to news from the ice, and especially to the fortunes of the Perseverance, sometimes fairly successful, more frequently not, and one unlucky year all but "clean"—a result traced eventually to the circumstance of the "captain" having been drunk most of the voyage. A burden was lifted off the heart of the wife when the share, involving so much uncertainty and anxiety, was sold; and the good folks at Ongar seem never to have considered a "share in a venture "quite a right thing to be concerned in.

The Lincolnshire coast lies opposite Hull, and in May 1820, Mrs Gilbert for the first time made the acquaintance of her husband's Lincolnshire relatives, spending a fortnight among the hospitable farm-houses sprinkled through the Wolds, and with the novel experience of riding on a pillion behind him.

Heavy anxiety rested over the latter part of the year from the dangerous illness of her father. To her mother she writes:—

"I fear that this long and anxious trial will prove very unfavourable both to you and to Isaac. I pray, my dear mother, that you may all be supported, and that as your day your strength may be also. We have the best of all consolations in the full persuasion that even at what we should call the worst, dear father has nothing to fear. The day which should grow darker and darker to us would grow brighter and brighter to him. Dear father is a happy man, whatever may now be before him, and whether you look backward or forward. I greatly enjoy to review his life from his youth up; with all its difficulties, it has been a cheerful ascending path. He has tasted all the best streams of earthly happiness, and enjoyed them all, and there is yet the river of the water of life, clear as crystal, of which he shall one day drink and thirst no more."

When it was possible to remove him, Isaac and Jane accompanied their father to Margate.

"How well," she says, "we can now see it to be that Jane and Isaac did not come into Yorkshire early in the summer, as we wished to contrive! Oh, upon how many things as life proceeds, do we look back and say they were well, though perhaps at first they appeared much otherwise! This day nine years we arrived at the Castle House, Ongar, and how well that has been! Do you remember what a beautiful evening it was?"

When a slow recovery led to thoughts of return, the anxious daughter at Hull writes—"Of course, you will not venture home by steam-packet, except in calm weather. They are perhaps less manageable even than sailing vessels, when the weather is so rough as to leave one wheel out of the water"—a singular apprehension, but no doubt expressing the nautical opinion of Hull at that time.

MEMORIALS OF MRS GILBERT.

CHAPTER II.

HULL.

CONTENTS OF CHAPTER II.

The "Peaked Farm" and its Inmates—Letters to her Husband, Father, and Sister—Cleethorpes—Death of Jane Taylor—Letter of Consolation to her Mother—Perplexity at Home—Departure from Hull.

CHAPTER II.

HULL.

1820-1825.

|

"Across its antique portico Tall poplar-trees their shadows throw." |

| LONGFELLOW. |

| "This river has been a terror to many; yea, the thoughts of it also have often frightened me; but now, methinks, I stand easy." |

| BUNYAN. |

MY mother treasured to the end of her life a thick volume, the gift of a friend at Hull. It was then the days of albums, and this was one; but it was rescued from the common fate of such by the use she made of it as a family record. She immediately appealed to the circle at Ongar for a worthy commencement, soliciting a contribution both in pen and pencil from each. A single withered oak leaf with an acorn, in water-colours, its rich yet pathetic tints of decay exquisitely rendered, was one of two drawings by her sister's hand. It was accompanied by the following sadly significant lines,—

"A faded leaf! and need the hand that drew

Say why from autumn's store it made this choice?

Stranger, the reason would not interest you,

And friends, to you the emblem has a voice.

"I might have plucked from rich October's bower

A fairer thing to grace this chosen spot;

A leaf still verdant, or a lingering flower,

I might have plucked them, but they pleased me not.

"A flower, though drooping, far too gay were found,

A leaf still verdant; Oh! it would not do!

But autumn shed a golden shower around,

And gave me this, and this I give to you.

"But should these tints—these rich autumnal dyes,

Appear too gay to suit the emblem well,

They are but dying tints, the verse replies,

A withered leaf, that faded ere it fell." *

Her brother Isaac, among other contributions, gave one in his favourite manner of firm yet fine outline, drawn with a camel-hair brush, representing a babe and a skull resting upon the surface of the round earth, while above, through a rent in the clouds, is seen the resurrection trumpet. Beneath is the legend,—"Dust! Dust!"

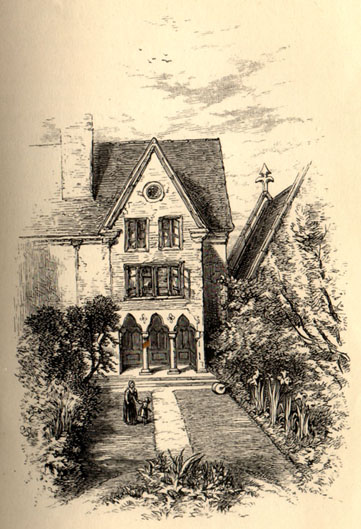

Her father inserted a vigorous water-colour drawing of the "peaked farm," his then residence, to match one in pencil, finished like an etching, of the Castle-House, by Jane. Her father's sketch set his daughter Ann's pen going, and upon the succeeding page she wrote,—

"There's a spot far away, where the distance is blue,

'Tis dear, 'tis delightful to me,

The traveller that passes returns to the view,

Half seen through the arched yew tree.

"There's a low white porch where the vine leaves cling,

And chimnies where fleet swallows play,

And there have they builded, in the merry time of spring,

Through many a good king's day.

"The tall old elm, which the evening light

Tips still, when the day is done,

How long has it creaked in the drear winter's night,

And waved in the summer's sun!

"And many are the feet which have danced in its shade,

When the harvest moon beamed high,

That now 'neath the churchyard trees are laid,

And O, how still they lie!

"But yet sweet spring, with her stir of leaves,

And her primrose breath moves on;

And the tame robin chirps from the vine-clad eaves,

As in years that are past and gone."

. . . . . .

The poem is too long to be quoted entire.

The "yew tree," the "vine-leaved porch," half the gabled peaks, one of the massive chimney stacks, the surrounding poplars, have all been improved away. The elm tree itself, last remnant of a rookery, has been lopped of its noble arms; and the garden has gone to ruin.

But at the time of our narrative the old house and its inhabitants offered a remarkable spectacle—a literary and artistic workshop. A large, low, wainscotted parlour was the common room for the very lively meals and winter- evening gatherings. At these the father sat in an arm-chair on one side the fire, the mother on the other, leaning with her hand behind her ear to catch the sounds; Isaac, Jane, Jefferys, Jemima, completed the circle. Some one might then read the last composition amidst a running fire of comments,—sarcastic from the mother, genial from the father, acute from Jane, sedate, though not without humour, from Isaac, droll from Jefferys; Jemima, the youngest of the circle, joining in occasionally with quiet little hits that left their mark. When Ann was of the party, pun and repartee abounded more than ever. The writer well remembers hearing his uncle Jefferys read the "Tolling Bell" one winter night, the wind roaring in the chimney, and wailing among the tall poplars outside, so that it became quite impossible to go to bed up the black oak creaking staircase, except well accompanied, and with a candle left in the room till sleep should come.

The father's study, furnished with the best English literature, opened from an adjoining passage, and on the other side of the same passage, what was called the "brown room" was entered. This was used for engraving, and was redolent of oil and asphaltum, of aquafortis and copper-plates, but always warm and cosy, and even picturesque, for it was oak pannelled, and the wide mantle piece displayed elaborate carving. Beyond this, a small room was fitted up as a cabinet for pictures, collected during the long art-life of the father, all of them good, and some carrying well-known names. Upstairs were roomy bedrooms; that of the father and mother opened into a small chamber over the "vine-clad porch," occupied as a study by the latter. Here were collected several family treasures, in the shape of china, books, and miniatures, and here her writing-table stood. Jane's bedroom, smaller than the rest, looked out behind, over the green meadows of the Roding Valley—but she has herself described the view. "Twilight already stealing over the landscape, shades yonder sloping corn field, whence the merry reapers have this day borne away the last sheaf. A party of gleaners have since gathered up the precious fragments. Now all are gone; the harvest moon is up; a low mist rising from the river floats in the valley. There is a gentle stirring amongst the leaves of the tall elm that shades our roof—all besides is still." *

Isaac's study, for he was now residing at home, was a strange remote place, approached by dark and narrow stairs across the kitchen and a dreary lumber-room. Its one window, high up, opened under the spreading branches of the elm tree, and had scarcely any other prospect. This room was not unpleasantly perfumed with Indian ink, his designs for books being always executed in that delicate pigment. Miniatures were also frequently in hand, and shelves were beginning to be laden with vellum-bound editions of the Fathers; but literary work was always carefully hidden away under lock and key. The "sanctum" of Jefferys was still more out of the way. A range of attics at the top of the house was unused; the floors of some were understood to be dangerous, and one of the huge stacks of chimnies was always regarded with anxiety by the inmates in windy weather. One of these attics, looking towards the west, between the waving poplars, and very rarely intruded upon by any but the owner, belonged to Jefferys, and contained, besides a few books, a turning lathe, and numerous odd bits of machinery; for, like his brother Isaac, he possessed a strong mechanical genius, and here invented a machine for ruling such portions of engraving work as required straight and close lines, which at one time was of much pecuniary advantage to him. Here, too, "Harry's Holiday," and "Æsop in Rhyme," were written, with other popular works; fragments of MSS. lay about carelessly enough.

Such was the dear old "rabbit-warren," as somebody called it, never long absent from my mother's thoughts in her distant home. When her husband once visited it without her, she writes to him:—

"I have, as you will believe, accompanied you in spirit along every foot of your road to Ongar—saw the laden coach climb the last woody hill, and heard its wheels grate upon the gravel, as it approached the well-known corner. There I saw Isaac's cheerful but sedate welcome, watched you, unseen, towards the white wicket, and saw the busy lights, thronging, with happy voices, into the porch, as your steps were heard. This, and much more, I have enjoyed in a little private picture gallery, of which I only have the key. It is hung round with many pleasing portraits, and some tender landscapes."

. . . . .

"I need not tell you how my heart has bounded at your account of our dear promising child; but be very cautious to betray to him nothing but affection and kind approval. Never let him read admiration in the corner of your eye. Do not let him hear a single word of his repeated, or have the praise of man substituted in his heart for the pure love of things, good and beautiful. Oh that he may be preserved from that vile pollution—the thirst for admiration, as it differs from approbation."

In the summer of 1821, she was herself at Ongar. From a batch of letters to her husband, we make a few extracts

"MY DEAR HUSBAND,—I cannot begin with an expression which means more to my own heart than this. It includes all that the world can do to make me happy, and it does make me happy indeed. If, by long experience, I had not learned to distrust myself, and to fear, from mischiefs no bigger than a midge's wing, I should look forward to our meeting again with unchastised delight. . . . I would rejoice to be your companion in the highest sense, and towards a still brighter happiness; but I fear that Hamilton gave me the key to many of my religious feelings in that word 'romance.' There is so much that is picturesque and poetic in the idea of travelling hand in hand to heaven, that it is hard to distinguish the false from the true. It is like church music, a dangerous test of devotion. One thing often affords me real consolation, and that is the belief expressed in your letter that it was Providence that united us. When I reflect on your prayers for direction, and remember that I was the answer—brought, as it were, from the ends of the earth, and as unlikely, as bread and water by the ravens, I cannot but believe that it was so. I might, indeed, suppose that I was selected from the world as the most appropriate trial that could be devised for you; but (not to mention that you tell me it is not so) I cannot but think you might have been made miserable, if need were, nearer home. It was sending you to a distant shop, indeed, if it was only to buy a rod."

"Perhaps we had both too much of poetry about us to be entrusted, at the outset, with the romance of love. I was not the vision of your early musings; as if on purpose to destroy that illusion, I was even less so than I might have been, and what I could have felt of enthusiasm, was strangely checked as by a spell. I was in fetters, when it would have been lawful and delightful to unbend, and the streams of affection which had been wandering for years through fields and flowers, seemed unnaturally thwarted, instead of being suffered to expand in the sunbeams which then began first to play upon them. I have often pondered over these circumstances, and have fancied that I could perceive the wisdom and still more the justice of them. But whatever we have lost, it is matter of no small thankfulness that the loss came first, and the gain afterwards."

"I was much pleased, the other day, with three quaint verses I met with, by Dr Donne, addressed to his wife; having nothing better to add, I transcribe them,—

"If we be two, we are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two,

Thy soul—the fixed foot—makes no show

To move, but doth if th'other do.

"And tho' it in the centre sit,

Yet when the other far doth roam,

It leans and hearkens after it,

And grows erect as that comes home.

"So shalt thou be to me, who must

Like th' other foot eccentric run,

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes an end where I begun.""An old-fashioned writer, in whom I found it, says that 'true conjugal love, on the part of the woman, is the love of her husband's wisdom; and true conjugal love, on the part of the man, is his love of her love of his wisdom!' Take heed, therefore, that I have wherewithal for this most excellent sorte of affection."

She fell in, at this time, with one of the Sunday school anniversaries—great occasions at Ongar, for there were then no other Sunday schools in the neighbourhood. The children arrived in tilted waggons and carts from outlying villages; an excellent dinner was provided for them and the visitors, in a large barn, decorated with flowers and evergreens, and two of the most eminent ministers of the day preached the sermons. Upon one occasion, Edward Irving, in the zenith of his fame, gave a magnificent oration, two hours long, upon the somewhat unsuitable subject of the battle of Armageddon, the chapel windows being taken out to allow a crowd outside to participate in the service.

"I retire," she writes, "from the pleasures of a very pleasant and busy day, to enjoy a sweeter hour of converse with you. Your welcome letter arrived just as we were beginning the bustle of our anniversary, which has gone off exceedingly well. Mr John Clayton preached in the morning, and Dr Ripon (a worthy fatherly man) in the afternoon, for an hour and twenty minutes, from the gospel of St Parenthesis, a loose paraphrase of which he gave from the first to the fiftieth chapter inclusive! We had beautiful weather, and besides the children, dined a party of a hundred, in the greenly decorated barn."

On the 17th of August 1821, her brother Isaac's birthday (thirty-four), she records in her diary—"Martin left us at four in the afternoon," and adds at a later date, "father, mother, Ann, Jane, Isaac, Martin, Jefferys, and Jemima, met for the last time in this world." On the 3d of September she and her sister Jane walked to the Castle House, returning, through the pleasant meadows which separated the two houses, to the "peaked farm." This was the last walk of the sisters together. The elder left next day for Hull.

In January 1822, writing for her father's birthday, she says—

"As to Ongar, and all that is dear to me in it, I do not know how to think, and, of course, not how to speak of it. It seems to me a sort of dream that you are going to leave the house, and how to think of you in the course of a few months I cannot tell. Yet Providence has always favoured your particular tastes, and allowed you something better than brick and mortar to look at, and I hope you may be equally favoured now. It will be in some respects no disadvantage to have both house and garden on a smaller scale, and if a little more air-tight within doors, so much the better also,—and then there are the chimnies! So that it may happen, as when you left the Castle, that you will not really regret the change, though the parting must be painful. Oh, that 'low white porch where the vine leaves cling'! I shall never forget it."

. . . . . . .

"And so in an hour or two after you receive this, I, if I live, shall be between forty and fifty! Nothing but registers, and almanacks, and pocket-books, and the most authentic traditions, could induce me to believe it! I feel just as young, for anything I can perceive, as ever, only with this difference, that I think of myself twenty years ago as a more disagreeable and foolish personage than I was then aware of. But it seems to me as if Luck, and Susan, and Anna, and Josiah, and Isaac, and Martin, and Jane, and I, were a kind of intermediate order of beings, never intended to grow old like other people in consequence of living long, but only to grow wise, and useful, and sober young people still."

The news about the house was too true. It was required by the landlord, and after much difficulty another was purchased in the outskirts of the town, with some pleasant views from the upper windows, but entirely unpicturesque in itself, and with a sadly small plot of garden attached. Mr Taylor built a study, and a cabinet for his pictures, adapted an outbuilding for his "brown room," and did wonders with the garden. His cheerful spirit conquered everything, but his daughter Jane, declining in health, suffered keenly in the change. Her sister, with much the same practical view of things as her father, speedily conformed to circumstances.

"I want (she writes) exceedingly a catalogue raisonée of your rooms, closets, and conveniences, that I may be able to feel my way pretty well about your new habitation. I have solid satisfaction in thinking of you in it, and airy regrets when I think of the other,—of which, indeed, I do not much like to think."

Her father sent her a drawing of the house, writing under it—

"My house again, my love, I am removed

From scenes so rural, and so well beloved.

One more remove, and then!—Ah, could I give

A sketch of that where next I hope to live!

Beyond my powers to paint, or yours to see,

Yet may I say, come there, and visit me."

Anxieties began to cloud the year of 1822. In the course of it her husband, whose failing health obliged him to spend much time away from Hull, sailed for Hamburg, to take part in an ordination there. A long and stormy passage home delayed his return till the hearts of the waiting ones were well-nigh sick.

"I cannot tell you (she writes), how we, and our friends for us, have watched both winds and tides; nor how many a dead flat of disappointment we have fallen into, when, after tracing vessel after vessel up the Humber, there was not at last the one we wanted. He was off a very dangerous shoal near the Elbe, during thirty-six hours of tremendous storm, and has scarcely been free from anxiety the whole time; but between seven and eight this morning we had one messenger after another to say the vessel was coming up, and most thankful we feel that he is in perfect health and safety, and finds all well. A vessel that left Hamburgh two days before is not in yet. Oh, the anxiety we should have endured if he had come by that, as he was recommended to do! The voyage was rough, but I believe they were borne on the prayers of two large and affectionate congregations—one at Nottingham and one at Hull.*

But the permanent anxiety was now her sister Jane, whose malady took her to Margate for several months, and who was besides deeply troubled by the circumstances of an attachment, to which there seemed little prospect of a happy ending.

"What I fear to hope I dare to pray" (wrote the elder sister), and on another occasion—

"I had felt, dear Jane, almost disposed to write to you, but, on consideration, I preferred leaving the case to better wisdom than either yours or mine. My husband and I, therefore, met for the express purpose on Sabbath evening, of commending you once more to the kind and wise influences of a superintending Providence. We have in seasons of difficult and anxious decision sought and found direction thus, for which we have felt constantly grateful when the event appeared. Few promises are more special than those which undertake to direct those concerns which are humbly placed in His hands. Scripture and experience are alike encouraging—"Is any afflicted let him pray: does any lack wisdom let him ask of God;" "Cast thy burden on the Lord and He will sustain thee; He shall direct thy steps." And there is one text still more express, but I cannot remember the exact words, but they are the words of God."

The following year (1823) she wrote to her sister—

"We must not murmur. The scene through which you have been led has been so evidently providential, so, as we may say, almost singularly contrived to distress you, so knit together by well ordered accidents and coincidences, that we cannot but regard it as a special interference in the course of your spiritual discipline. Though we may look upon every affliction as designed for benefit, yet there are some (and this is one) in which the shaft seems to be more than commonly pointed, and sent with direct almost articulate aim. It is the Lord's doing, and who can feel a doubt that the end will be, you shall come forth as gold? It is, I had almost said, the natural element of our mental constitution to live in spiritual darkness; not to breathe the free air, nor enjoy the clear shining of that grace which is in the gospel. But it is free grace nevertheless; free in the offer, free in the administration, over above, and notwithstanding all our iniquities. . . . Take the consolation, dear Jane, of this distinguishing feature of Christianity, and do not suffer the enemy of your peace to embue you with feelings (for I cannot in your case call them views) less evangelical. I could not and would not endeavour to rest your hope on any review of past usefulness, but when you spoke of a 'life misimproved,' I could not help thinking how few had been able to reach the extent to which you have served religion in your writings, every word of which has a direct Christian bearing, and that with an inviting sweetness and "naiveté," which will give them influence, and make impression, where many a sermon would have failed."

On the 30th of January this year, the family festival, she wrote of her father—

"He and I seem growing nearer and nearer each other every year, though with one and forty years over my head I cannot yet feel myself a middle-aged woman. I cannot believe that 'The Associate Minstrels' are all past the prime of life, not one of them young any longer! In a very few years, if they are spared, J. and A. will take the standing that we once held; may they be wiser and better, and therefore happier. I will not grudge them any improvement on the original pattern. On our wedding-day (Dec. 24) we had our Christmas dinner, and afterwards sat round a blazing Yule clog according to our ages; the baby fastened in his chair by the parlour broom, and a vacant chair being placed by me for dear J— at which a kiss was regularly left as it went round."

The following quotation will explain how what was to her the happy event of that year came about:—

"It has been, I may say, for years our wish to see J— once more among his brothers and sisters at our fireside, that his right to the situation may not be imperceptibly questioned; that that principle which is truly second nature may not be wholly wanting to strengthen the domestic affections between us; that he and we, in short, may feel as well as know our relationship. I have seen lovely children, who, from being long separated from their families in childhood, have never seemed to regain their full relationship, and have been treated more like children-in-law than anything else on their return. To prevent even the possibility of such feelings among us, we have, after long and frequent deliberation, and not without counting the cost, determined that once before his final return our dear boy should come and lay claim to his brothers and sisters, and take up the freedom of his father's house."

He was to meet them all, their friends the Cowies included, at the sea-side, and a small house was taken at Cleethorpes at the mouth of the Humber. It was then a sequestered village, separated from Grimsby by three miles of open common, that charming, but nearly extinct feature of English scenery.

"On Tuesday, June 17, we sailed, as proposed, at one, after such a bustle as you may conceive, if you sit down and shut your eyes, and think about it, but not else. We had a fine passage of two hours and a-half—I terribly sick, Mrs Cowie more terribly frightened, and Ann, Jane, and Edward all ill together, so that I could not help laughing in spite of my own calamity. At Grimsby, having piled up two carts within half a foot of safety, we set off over a pleasant heath with our straggling regiment, and got into very cheerful lodgings to a hearty tea at six."

Here, a week later,—

"From our upper windows, by help of a good telescope, we had the pleasure of seeing the Grimsby packets discharging their passengers, and at half-past nine Mr Gilbert and J— made their appearance, J— having run or danced all the way. Then came a day of complete riot; one and all the children seemed wild. To-day we are all a little soberer, but still enjoying ourselves quite sufficiently."

July 17, they all returned to Hull, on a fine but blowing morning. "I thought if dear mother could have seen us in the boat which conveyed us to the vessel, dancing like a cork on the waves, she would have given all up for lost."

The next night her husband was seized with pleurisy, and had a dangerous relapse a fortnight afterwards. As soon as he was able he was removed to Harrogate, and the family union so long looked forward to, was broken up. However anxious might be the wife at home, she always wrote trustfully and cheerfully:—"I am content to like disagreeable things if I can. It is the only way in my power of making them agreeable, and there are very few things that I have met with that have not something or other about them better than might have been."

But the year closed peacefully. J—, now nine years old, returned to Ongar in November, encountering some peril from extraordinary floods, which carried away bridges, and filled roadside public-houses with the passengers, coachmen, and guards of the long north mails, detained till by aid of many men and horses they could be dragged through the wreck. At one point, in the night, the doors of the coach were set open to allow the free rushing of the water through, while with torches and shouting it was hauled over a water-course.

At the end of the year, his mother, as she often did at that season, reviewed the characters and progress of her children. Of one she says:—

"He is trying hard, as they have all done about his age, to establish the doctrine of Divine right. He is indeed quite a Stuart, but I hope to continue Mrs Cromwell notwithstanding. He has one naughty trick, most amusing to witness, most dangerous to indulge. When accused of a misdemeanour, though caught beyond all contradiction in the very fact, he exclaims, with vehement indignation, 'I didn't! I didn't!' I am sure he does not understand the grammatical meaning, but only perceives it to be an approved mode of justification when it can be maintained."

1824 was the year that severed Ann and Jane for ever in this world, but, though very ill, there seems to have been little expectation that the life of the latter was so soon to close. Less than a month before (March 16), the elder sister, after urging, as so frequently during the last year or two the claims of some new remedy, turns to other subjects, and quotes from a letter recently received from Montgomery, who had been soliciting contributions to the "Climbing Boys' Album," an attempt to interest the public in the miserable condition of the poor red-eyed little fellows.

"'When you write to Jane,' he says, 'pray say that I am yet alive at this date, and alive to all the kind remembrances of former years, when we occasionally met in company or in print. In the latter, I know not when I have seen her, and am sorry that she could not put her beautiful little spirit into three or four stanzas for our poor climbing lads, but I should have been more sorry if she had put that spirit on the poetical rack to please me at any expense of suffering.' 'Should this find her better, it is not yet too late.' Of my contribution he says (if I may be allowed to repeat it), that 'it is truth, nature, humanity, in the mother tongue of all three.' You will see it, if you wish, when the work appears, it being too long to transcribe—more than 150 lines written before night on the day of receiving his application, so my family has not to reproach me with wasting much time over it."

On the 28th of March she writes her last letter to Jane, telling her that as she was about to accompany her husband to Nottingham, where he was engaged to take part in the ordination of Richard Cecil, who, with his wife (Salome), was just settled there, they thought of extending their journey to Ongar:—

"I only wish, dear Jane, there were nothing to abate the pleasure of the visit. I will hope that you may have improved greatly by that time, but, after all, the peace of your mind is a mercy that ought to counterbalance in our feelings all the trial. 'To read your title clear' ought to enable you, and all of us, to say, 'let cares like a wild deluge come.' You have indeed borne a heavy blast of affliction since we last met, but are they not light afflictions compared with the joy that shall be revealed? My dear Jane, may you be supported beyond yourself, your own hopes, your own expectations. It is our daily prayer."

On the 12th of April they left Hull, reached Newark at half-past six the next day, and on a beautiful evening (Tuesday the 13th), as she records in her diary, went over the fine castle ruin, all unknowing that an hour before at Ongar, the father, the mother, the brother, and the sister, had witnessed the last sigh of Jane Taylor. On the 14th, alarmed by the tenor of a letter from her brother Isaac which met her at Nottingham, she writes that if they can obtain places in any of the coaches, they hope to reach Ongar on Friday evening, adding, "Dear Jane, my tenderest love to you." This they did; passing through London, she learned from her brother Martin that she was too late, and at six that evening she and her husband joined the sorrowing circle in the house thus early consecrated by death. The day after the funeral she wrote the following letter to her eldest daughter:—

"My dear child.—As I wish you never to forget your dear aunt Jane, and as my best hope and prayer for you are that you may live and die as she did, I write this letter for you to keep. Often read it over, and think to yourself—'Well, the same God who made dear aunt Jane good and useful, will make me so too if I wish, and pray, and try for it.'

"I am now writing, my dear A— in the room in which she died, and where I have been many times every day to look at her. She looked very pleasant, but so still and cold! They tell me that at first, just after she died, there was a beautiful expression in her face, and about her mouth especially, like the smile that a person has when they feel inwardly very happy—more happy than they could tell you—and this was certainly the look which she gave just as her departing spirit caught sight, as I may say, of heaven. O, my dear child, what a feeling that must have been! Do not you think it worth while denying yourself, and resisting temptation for it? Your dear aunt had been able to sit down stairs every day till that on which she died. Uncle Isaac used to carry her up and down stairs in his arms, and you may be sure it is a great comfort to him, now his sister is gone, to remember how kind he was to her; always think of this, my love, when you are disposed to be unkind to your brothers and sisters, and say to yourself, 'how should I like to think of this if they were dead?' On Tuesday morning he lifted her out of bed to her easy chair, where she sat two or three hours and talked a little, as well as her weakness would let her, about dying. She said, 'How good God is to me to let me die without pain!' She repeated that beautiful verse—

Jesus, to thy dear faithful hand

My naked soul I trust,

And my flesh waits for thy command

To drop into the dust.This she said very strongly, and repeated, 'My naked soul—my naked soul.' About one or two o'clock she said she was very tired, and begged they would lay her down. She said, 'Put me on a clean cap, and set the room to rights, for I am going.' After this grandpapa asked her how she felt, she replied with a very firm voice, 'Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will fear no evil.' Most of the afternoon she lay quite still, breathing quick, and turning her eyes about as if reading. About a quarter of an hour before she died, uncle Isaac asked her if she felt any pain, and she said, 'No, dear, only a little sleepy.' Those were the last words she said, and about five and twenty minutes before six, she gave one long sigh, and died.

"Oh, how happy I should be if I could know that you and I, dear A., and your dear papa, and dear J. and H., and E. and J., and Chas. and C., would all die like her, beloved by all who knew us, and carried by angels, as we believe she was, directly to heaven! You see how kindly Jesus conducted her through that deep river which you know Bunyan says was so shallow sometimes that they passed almost dryshod. This was just the case with her. She had often been like 'Much-afraid,' but God was better to her than her fears, and made her death more like falling asleep than dying. Yesterday morning the coffin was brought down into uncle Isaac's study, and after breakfast we all went in to look at her for the last time. Oh, it was such a thought that her eyes would never open till the last trumpet should sound, and the grave should break open, to let her meet the Lord in the air! At twelve o'clock we began to move to the chapel, which is very near. First the coffin, then grandpapa and I, then uncle Isaac and aunt Jemima, then uncle Martin and uncle Jefferys, and then papa and J. She lies close by a tall poplar near the vestry door, and poor grandmamma was at one of the back windows here, and could see her let down into the grave. There is only a garden and one field between. Though we all grieve very much, yet we are all comforted and thankful to think of the goodness of God towards her. She was in her life kind, tender, active, generous, and always anxious to be useful to others. She was willing to deny herself of everything, and was never so happy as when she was doing a kindness to her brothers and sisters. Above all, she feared God from her youth, and did not leave that great work till she came to die. May this be your case, my dear children, and then I shall be your happy, as well as your affectionate mother,

ANN GILBERT."

To her friend Mrs Whitty she writes:—

"You will believe that there is not one of us to whom it is a light trial. My father and mother are both deeply affected, and from what I know of the latter I fear the wound will never heal. Dear Isaac has lost his friend, his nurse, his most endeared associate, one with whom he took sweet counsel, and such a loss he feels it. His sweet assiduities during the whole course of her illness were all that affection could desire, and that strength could sustain. Dear Jemima feels most severely bereaved, for her only female companion is gone, one who was always awake to her interests, and active to promote all her pleasures. My heart fails me more than ever at the thought of parting, though I have one less to leave, but I cannot help feeling that sorrows have now begun. But as soon as I set my face fairly northward, I shall feel the glow of what I am going to. It is a mercy to have two such homes, but you see as the old divine says, "though these pleasures have crowns on their heads, they have stings in their tails."

After reaching home she wrote to her mother—

"Most thankful should I be if I knew the balm by which the sufferings of a 'deeply wounded and bleeding heart' might be soothed, and, indeed, there are so many sources of comfort in this cup of affliction that it seems easy and almost trite to point to them. Do, my dear mother, make the strongest daily effort to resist what is doubtless a temptation, too fitly addressed to your natural feeling, and bodily sensibility. O, how many parents would be ready to expend their remaining lives in thankfulness for anything like the consolation in their losses, which you have in yours!"

"For what purpose were you made a mother? not certainly to rear children who should live for ever in this world. What would you have asked, if, at the birth of dear Jane, you could have been offered any lot you might choose for her? Would you not have been ready to say, 'O let her be but a Christian, and if I survive her let me feel an assured hope of her immortal happiness, and I am little anxious about the rest.' But suppose, that having this granted, so much more had been freely added as has been bestowed on her. Suppose you had received the promise that she should be gifted with eminent talents, all of which should be devoted to eminent usefulness; and that after receiving favours from Providence such as is the lot of but here and there a distinguished mind, she should fall asleep in Jesus without one of those pangs, or those fears, that render death terrible, would not your heart have overflowed with gratitude? If the giving of the promise would have been esteemed so great a mercy, why should the fulfilment of it be felt so inconsolable a trail? . . ."

The sorrow at Ongar led in a singular manner to an occasion for joy, in the engagement of Isaac Taylor to the young lady who afterwards became his wife. But her brother's usual reticence drew from his absent sister a characteristic request—

"I am sure I rejoice with those that do rejoice, and hope they are not few, but I sadly want information beyond the bare fact. My mind likes to walk in a defined path, with a close fence of particulars, as I suppose you know. Let anybody who feels disposed give me at least as many as may enable me to find my way without stumbling."

It was from her husband, during a hasty visit to Ongar, that she learnt something of what she wanted, and especially of her brother's new home—

July 21, 1825.—"A most pleasant ride brought me to Stanford Rivers; there I was arrested in my journey by Isaac, Jemima, and J—, and after looking round the delightful domain of your brother, came here by a pleasant footpath to sleep. Isaac is really situated just as I have always thought I should like to be: the house neat, commodious, comfortable, pleasantly surrounded with clean gravel walks, grass plots, roses, fruit—everything that is 'pleasant to the eye and good for food.' It is just what one would like to take a simple-hearted, tender, good tempered, cheerful, kind, contented young bride to. They are to be happy in less than a month."