HOW

THE GUBBAUN SAOR

GOT HIS TRADE

HOW THE GUBBAUN SAOR GOT HIS TRADE

![[illuminated capital] I](I.png) T

was drawing towards night, and the Gubbaun had not given a thought to his sleeping place. All about him was sky, and a country that looked as if the People of the Gods of Dana had been casting shoulder-stones in it since the beginning of time. As far as the Gubbaun's eyes travelled there was nothing but stone; gray stone, silver stone, stone with veins of crystal and amethyst, stone that was purple to blackness; tussocks and mounds of stone; plateaus and crags and jutting peaks of stone; wide endless, spreading deserts of stone. Like a jagged cloud, far-off, a city climbed the horizon.

T

was drawing towards night, and the Gubbaun had not given a thought to his sleeping place. All about him was sky, and a country that looked as if the People of the Gods of Dana had been casting shoulder-stones in it since the beginning of time. As far as the Gubbaun's eyes travelled there was nothing but stone; gray stone, silver stone, stone with veins of crystal and amethyst, stone that was purple to blackness; tussocks and mounds of stone; plateaus and crags and jutting peaks of stone; wide endless, spreading deserts of stone. Like a jagged cloud, far-off, a city climbed the horizon.

The Gubbaun sat down. He drew a barley-cake from his wallet, and some cresses. He ate his fill and stretched himself to sleep.

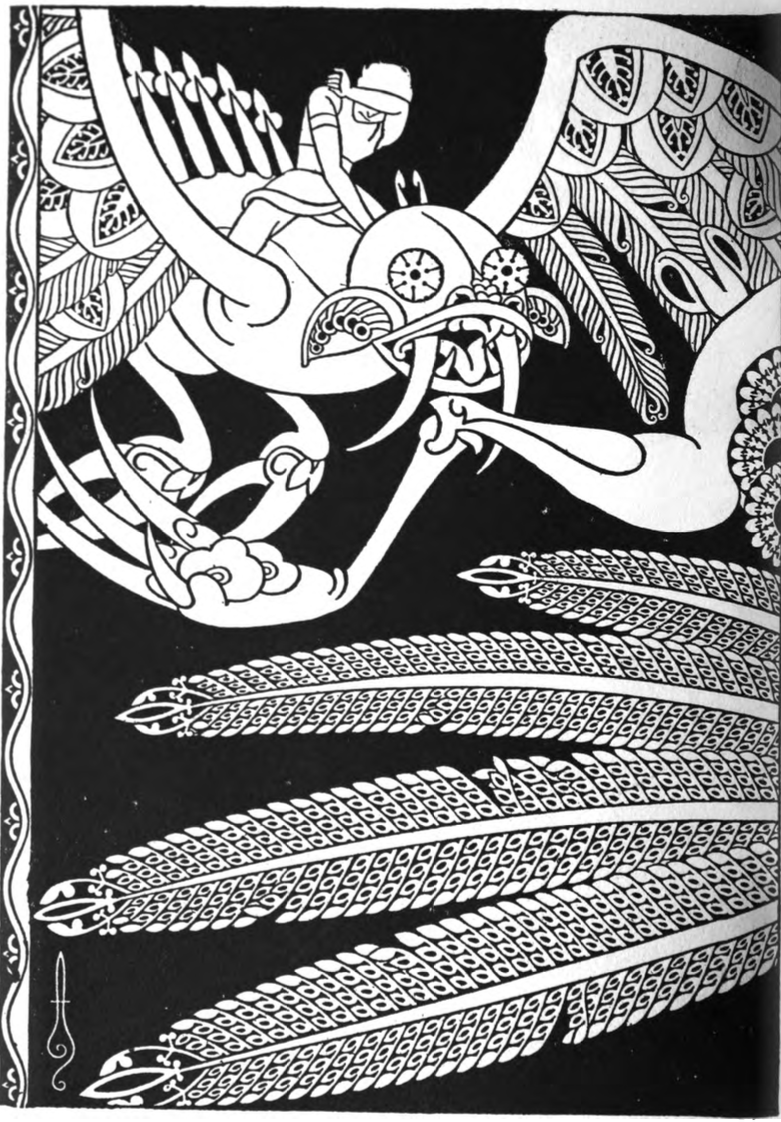

The pallor of dawn was in the air when a shriek tore the sleep from him. He sat up: great wings beat the sky making darkness above him, and something dropped to the earth within hand-reach. He fingered it–a bag of tools! As he touched them he knew that he had skill to use them though his hands had never hardened under a tool in his life. He slung the wallet on his shoulder and set off towards the town.

As he neared it he was aware of a commotion among the townsfolk–they ran hither and thither; they stared at the sky; they clung together in groups.

"What has happened to your town?" said the Gubbaun to a man he met.

"A great misfortune has happened," said the man. "This town, as you can see, has the noblest buildings in the world: poets have made songs about this town. This town is itself a song, a boast, a splendour, a cry of astonishment! Men wonder at this town. The djinns, craning from battlemented storm-winds, have no pride left in them: they are shamefaced before this town.

"Three Master-Builders came to this town–builders that had not their fellows on the ridge of the world. They set themselves to the making of a Marvel; a Wonder of Wonders; a Cause of Astonishment and Envy; a Jewel; a Masterpiece in this town of masterpieces–this place that is jewelled like the Tree of Heaven and drunken with Marvels!

"One pact alone, one obligation they bound with oath on the townsfolk–no living person was to come within the enclosure where they worked; no living person–man, woman, or child–was to set eyes on them when they passed through the town with the tools of their trade in their hands.

"It was Geas for them to be looked on.

"We cloaked our eyes when they passed, we darkened our windows when they passed, we closed our doors.

"Three days they were working and passing through the town with the tools of their trade. We had contentment, and luck and prosperity, till the whitening of this dawn. Then a red-polled woman thrust her head forth–my curse on the breed and seed of her for seven generations–she set the edge of her eyes on the Three Master-Builders. They let a screech out of them and rose in the air. They put the shapes of birds on themselves and flew away–my grief, three black crows!

"Now the stone waits for the hammer: and the hammer is lost with the hand that held it!"

The Gubbaun tightened his grasp on the wallet, and his feet took him of their own accord away from the town.

"The tools have come to the man who can handle them," said the Gubbaun to himself; "but I'll handle them for the first time where there are fewer tongues to wag."

HOW

THE GUBBAUN

PROVED HIMSELF

HOW THE GUBBAUN PROVED HIMSELF

![[illuminated capital] T flanked by horses](T.png) HE Gubbaun wandered at his own will, as the wind wanders. Every place seemed good to him, because his heart was happy.

HE Gubbaun wandered at his own will, as the wind wanders. Every place seemed good to him, because his heart was happy.

He sat by a river cataract and watched the leap of a great king-salmon, silver against the swirling flood.

"My blessing on you, Brother," he cried, "and your own heart's wish to you."

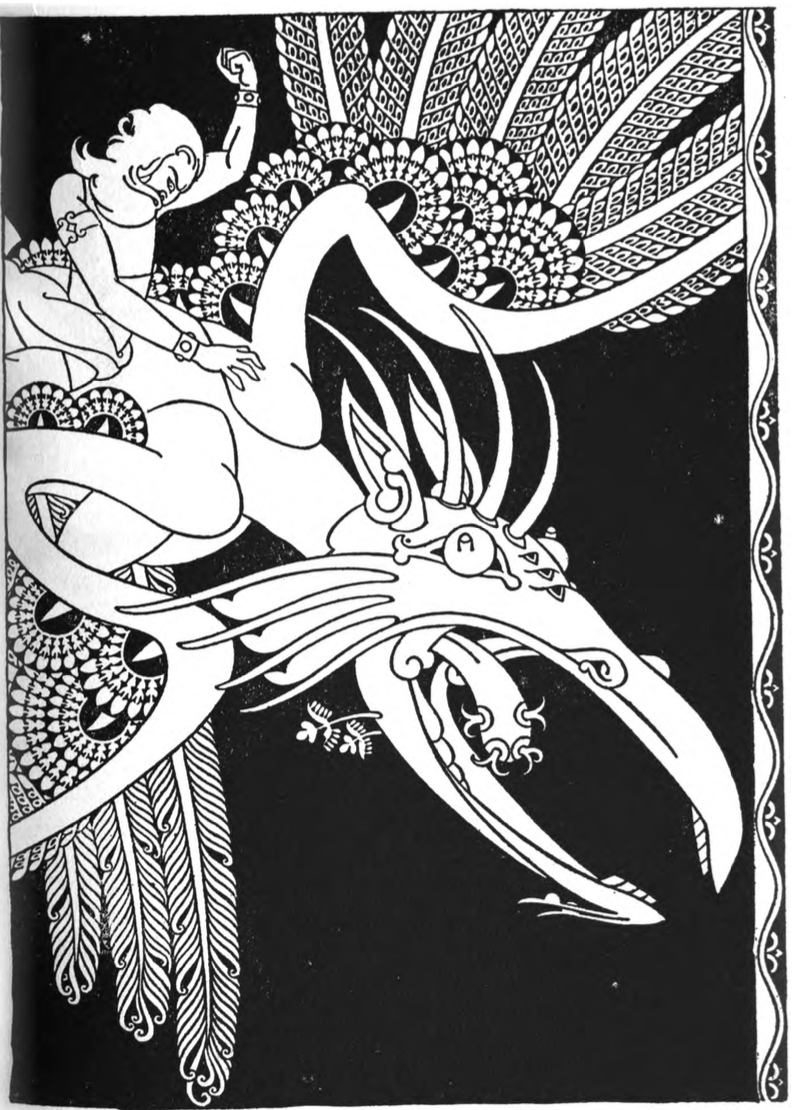

With that a Pooka lifted himself head and shoulders from the spume. He had put the shape of a white stallion on himself. His eyes were blue like ice.

"If you blessed me," he said, "I could take you to the Land-Under-Wave, to the Plain with Red Blossoms."

"I know that Plain," said the Gubbaun; "but it is work on the world-ridge that I am seeking now. I would prove myself and my tools."

"The sun and wind, the rain and hail, will eat into your work. Old age will gnaw at the roots of it. Put your hand on my neck, and your blessing on me!"

"My blessing to you, Brother of mine; White Love of Running Water; White Wave of the Turbulent Sea. I will win you lovers and new kingdoms. You shall be a song in the heart; a dream that slips from city to city; a flame; a whiteness of peace in the murk of battle; a honied laughter; a quenchless delight. These, O my Brother, because of me: and at the last, my hand upon your neck."

"Call, and I follow," said the Pooka:

"I am a Hound whiter than the sun.

A Stag I am with golden antlers.

A Tree I am with silver fruit.

A Voice in the wind's voice I am.

I am running water and growing grass.

Take my blessing, Master-Builder; take my blessing, Wonder-Smith."

"If I am sun to-day, and you the shadow," said the Gubbaun, "to-morrow you are sun, and I the shadow. Day in, day out, let there be love between us–and no farewell."

The Gubbaun shouldered his tools.

Walking at his will, he came to a place where a great chief's dune was a-building. The folk that fashioned it were disputing and arguing among themselves.

"It is right," said one who had an air of authority and a red cloak on him; "it is right that on this lintel there should be

"MY BLESSING TO YOU, BROTHER OF MINE; WHITE LOVE OF RUNNING WATER."

Page 32

an emblem to show the power of the lord of the dune–an emblem to put loosening of joints and terror upon evil-doers."

"It is more fitting," said another, "that the man who carves the emblem should be honoured in it."

"Nay," said a third, "the man who raised the stone should be honoured in it. I myself should be honoured."

So the clash of tongues and opinions went on.

"The blessing of the sun, and the colours of the day to you," said the Gubbaun. "Have ye work for a Craftsman?"

"What Craftsman are you," said they, "that come hither a-begging? The world runs after the Master-Craftsman–we have no need of bunglers!"

"I am a Master-Craftsman."

"Hear him!" cried they all. "Where are your apprentices? What dunes have you built? What jewels have you carved? Tell us that!"

"A man with ill-cobbled brogues, and burrs in his coat–a likely lie!"

"Put me to the proof," said the Gubbaun, "set me a task!"

"So vagrants talk," said the man in the red cloak, "while good men sweat at labour. Have you the hands of a mason?"

"What need to waste wit and words on this churl?" cried another. "It is time now to stretch our limbs in the sun, and to eat. Let us go to the stream where the cresses are."

They went.

When they were well out of the way, the Gubbaun took his tools. He worked with a will. The work was finished when they straggled back.

The first that caught sight of it cried out: the cry ran from man to man of them. There was hand-clapping and amazement.

The Gubbaun had carved the King-Cat of Keshcorran–more terrible than a tiger! The Cat crouched midway in the lintel, and on either side of him spread a tail, a tail worthy that Royal One! Bristling with fierceness it spread; it slid along on either side, with insinuating grace and with infinite cunning, losing itself at the last in loops, and twists, and foliations and intricacies that spread and returned and established themselves in a mysterious, magical, spell-knotted forest of emblems behind the flat-eared threatening head.

"There is an emblem for the Builder in that," said the Gubbaun, "and an emblem for the Carver, and an emblem for the Man who Planned the Dune, and for the Earth that gave the stone for it. Is it enough?"

"It is enough, O Master-Craftsman, our Choice you are! Our Share of Luck you are! Our treasure! Stay with us. The chief seat in our assembly shall be yours. The chief voice in our council shall be yours. Stay with us, Royal Craftsman."

"I have the wisdom of running water and growing grass," said the Gubbaun, "and my feet must carry me further–still water is stagnant! May every day bring laughter to your mouths, and skill to your fingers; may the cloaks of night bring wisdom."

He left them.

Often he was wandering after that when the sun was proud in the sky–and often when the sun was under the earth. He drank honey-mead in Faery-Mounds. He saw the Mountain-Sprites dancing. At last he built a noble habitation for the one daughter that he had and for himself. Aunya was the daughter's name. She had the cleverness of her father, but the Gubbaun's heart was set on a son.

HOW

THE GUBBAUN SAOR

GOT HIS SON

HOW THE GUBBAUN SAOR GOT HIS SON

![[illuminated capital] T flanked by horses](T.png) HE

Gubbaun Saor sat outside in the sunshine, but it's little joy he had of the good day. He was wringing his hands and making lamentation.

HE

Gubbaun Saor sat outside in the sunshine, but it's little joy he had of the good day. He was wringing his hands and making lamentation.

"Ochone! Ochone!" he said, "my share of sorrow and the world's misfortune! Why was I given any cleverness at all, with nothing but a daughter to leave it to? Ochone!"

At that he heard a lamentation coming down the road. It was a woman raising an ullagone, clapping her hands like one distracted. She stopped when she came to the Gubbaun.

"What has happened to you, Jewel of the World," said she, "to be making lamentations?"

"Why wouldn't I make lamentations," said the Gubbaun, "when I have no one but a daughter to leave my cleverness to? 'Tis a hard thing to have all the trades in the world, and no one but a daughter to learn them!"

"The topmost berry is always sweet," said the woman, "and the red apple that is beyond us draws our hearts. You are crying salt tears for a son, and I would give the world for a daughter."

"O, what good is a daughter!" said the Gubbaun. "What good's a girl to a man that has robbed the crows of their cleverness and taught tricks to the foxes?"

"Maybe you'd be worse off," said the woman, "if you had a son. Isn't it myself that is making a hand-clapping and shedding the salt tears out of my eyes because of the son I've got–a heart-scald from sunrise to candle-light!"

"'Tis you," said the Gubbaun, "that don't know how to manage a son. He'd be a lamb of gentleness if I had him.”

"O then take him," said the woman, "and give me your daughter. I'll be well content with the bargain!"

It was agreed between them, then and there. The Gubbaun took the son and the woman got the daughter. She went away after that and left no tidings of herself: she thought it likely the Gubbaun would rue the bargain.

The Gubbaun started to teach the son. He had systems and precepts and infallible methods of teaching, but the boy would not learn. He would do nothing but sit in the sunshine and play little tunes on a flute he had made. He grew up like that.

"Clever as I am," said the Gubbaun, "the woman that got my daughter got the better of me. If I had Aunya back again, 'tis I that would be praising the world. My share of grief and misfortune! Why did I give the red apple for the unripe crab?"

He beat his hands together and lamented: but the son in a pool of sunshine played a faery reel, and two blackbirds danced to it.

HOW THE

GUBBAUN TRIED HIS HAND

AT MATCH-MAKING

HOW THE GUBBAUN TRIED HIS HAND AT MATCH-MAKING

![[illuminated capital] O with intertwining creatures](O.png) NE day the Gubbaun roused himself:

NE day the Gubbaun roused himself:

"What my son needs," said he, "is a clever woman for a wife, and 'tis I that will choose one."

He gave out the news to the countryside, and many a woman came bragging of the daughter she had.

"The eye that looks on its own sees little blemish," said the Gubbaun. "I'll take no cleverness on hearsay: before I make a match for my son, I must talk to the girl he is to get."

It would take a year to tell of the girls that came, with their mothers to put a luck-word on them, and the girls that went, disheartened from the Gubbaun Saor. He out-baffled them with questions. He tripped and bewildered them with his cleverness. There was not a girl in the country-side wise enough to please him. Three girls, with a great reputation, came from a distance.

When the first girl came, the Gubbaun showed her a room heaped up with gold and treasure and the riches of the world.

"That is what the woman will get that marries my son," said he.

"There would be good spending in that pile!" said the girl. "You could be taking the full of your two hands out of it from morning till night every day in the year."

"'Tis not you will be taking the full of your two hands out of it," said the Gubbaun. "My son will get a wiser woman."

The second girl came. The Gubbaun showed her the heap of treasure.

"I'll put seven bolts and seven bars on it," she said, "and in a hundred years it will not grow less!"

"'Tis not you will put the bolts and bars on it," said the Gubbaun. "My son will get a wiser woman."

The third girl came. The Gubbaun showed her the heap of treasure.

"Big as it is," said she, "it will be lonesome if it is not added to!"

"I wonder," said the Gubbaun, "if you have the wit to add to it."

"Try me," said the girl.

"I will," said the Gubbaun. "Bargain with me for a sheepskin."

"If you have the wit to sell," said she, "I have the wit to buy. Show me the skin and name your price."

He showed the skin; he named his price. It was a small price. She made it

HE SET OUT THEN WITH THE HOUND TO TRAVEL THE SOLITARY PLACES AND MARTS OF THE WORLD.

Page 63

smaller. The Gubbaun gave in to her.

"You have a bargain in it," said the Gubbaun; "the money-handsel to me."

"You'll get that," said she, "when I have the skin."

"That's not my way at all," said the Gubbaun, "I must have the skin and the price of it."

"May Death never trip you till you get it!"

"I will get it from a woman that will come well out of the deal–and know her advantage!"

"May your luck blossom," said the girl, "'tis ransacking the faery hills you'll be: or bargaining with the Hag of the Ford."

"Health and Prosperity to yourself!" said the Gubbaun.

She went out from him at that, but the Gubbaun sat with his mind turned inward, considering, considering–and considering.

HOW THE

SON OF THE GUBBAUN

MET WITH GOOD LUCK

HOW THE SON OF THE GUBBAUN MET WITH GOOD LUCK

![[illuminated capital] I flanked by birdlike creatures](I.png) T would be well for you to be raising a hand on your own behalf, now," said the Gubbaun Saor to his Son, "you can draw the birds from the bushes with one note of your flute: maybe you can draw luck with a woman. If you have the luck to get the daughter I gave in exchange for yourself, our good days will begin."

T would be well for you to be raising a hand on your own behalf, now," said the Gubbaun Saor to his Son, "you can draw the birds from the bushes with one note of your flute: maybe you can draw luck with a woman. If you have the luck to get the daughter I gave in exchange for yourself, our good days will begin."

The Son of the Gubbaun got to his feet.

"I could travel the world," he said, "with my reed-flute and the Hound that came to me out of the Wood of Gold and Silver Yew Trees." With that he gave a low call, and a milk-white Hound came running to the door.

"Is it without counsel and without advice and without a road-blessing," cried the Gubbaun, "that you are setting out to travel the world? How will you know what girl has the fire of wisdom in her mind? What sign, what token will you ask of her?"

"'Tis you that have wisdom: give me an advice," said the Son.

"Take the sheepskin," said the Gubbaun, "and set yourself to find a buyer for it. The girl that will give you the skin and the price of it is the girl that will bring good-luck across this threshold. The day and the hour that you find her, send home the Hound that I may know of her and set out the riches of this house."

"Tree of Wisdom," said the Son, "bear fruit and blossom on your branches. The road blessing now to me."

"My blessing on the road that is smooth," said the Gubbaun, "and on the rough road through the quagmire. A blessing on night with the stars; and night when the stars are quenched. A blessing on the clear sky of day; and day that is choked with the thunder. May my blessing run before you. May my blessing guard you on the right hand and on the left. May my blessing follow you as your shadow follows. Take my road-blessing," said the Gubbaun.

"The shelter of the Hazel Boughs to you, Salmon of Wisdom," said the Son.

He set out then with the Hound to travel the solitary places and the marts of the world. He shook the dust of many a town from his feet, but the sheepskin remained on his shoulder. A cause of merriment that skin was; a target for shafts of wit; a shaming of face to the man that carried it. It found its way into proverbs

"OUR KING BESPEAKS YOUR HELP. BEHOLD THE GIFTS AND TOKENS OF BALOR!"

Page 99

and wonder tales, but it never found the bargain-clinch of a buyer.

If it hadn't been for the Hound, and the reed-flute, and the share of songs that he had, the Son of the Gubbaun Saor would have been worn to a skin of misery like a dried-up crab-apple!

One day, in the teeth of the North Wind, he climbed a hill-gap and came all at once on a green plain. There was only one tree in that plain, but everywhere scarlet blossoms trembled through the grass. Beneath the tree was a well: and from the well a girl came towards him. Her heavy hair was like spun gold. She walked lightly and proudly. The Son of the Gubbaun thought it long till he could change words with her.

"May every day bring luck and blessing to you," he cried.

"The like wish to yourself," said she, "and may your load be light."

"A good wish," said he, "I have far to carry my load."

"How far?" asked the girl.

"To the world's end, I think."

"Are you under enchantment?" said she. "Did a Hag of the Storm put a spell on you; or a Faery-Woman take you in her net?"

"'Tis the net of my father's wisdom that I am caught in," said he. "I must carry this sheepskin, my grief! till a woman gives me the price of it: and the skin itself, in the clinch of a good buyer's bargain."

"You need go no farther for that,” said the girl. "Name your price for the skin."

He named his price. She took the skin. She plucked the wool from it. She gave him the skin and the price together.

"Luck on your hand," said he, "is the bargain a good one?"

"It is," said she, "I have fine pure wool for the price of a skin. May the price be a luck-penny!"

"You are the Woman my father brags of," cried the Son. "My Choice, My Share of the World you are, if you will come with me."

"I will come," said the girl.

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor called to the Hound.

"Swift One," he said, "our fortunes have blossomed. Set out now, and don't let the wind that is behind you catch you up, or the wind that is in front of you outrace you, till you lie down by the Gubbaun Saor's threshold."

The Hound stretched himself in his running. He was like a salmon that silvers in mid-leap; like the wind through a forest of sedges; like the sun-track on dark waters: and he was like that in his running till he lay down by the Gubbaun Saor's threshold.

HOW THE GUBBAUN SAOR

WELCOMED HOME

HIS DAUGHTER

HOW THE GUBBAUN SAOR WELCOMED HOME HIS DAUGHTER

![[illuminated capital] M with bird and animal heads](M.png) ANY a time the Gubbaun looked forth to see was the Hound coming. He was tired of looking forth. He flung himself on the bench he had carved, by the hearth-stone.

ANY a time the Gubbaun looked forth to see was the Hound coming. He was tired of looking forth. He flung himself on the bench he had carved, by the hearth-stone.

"I wish I never had a son!" he said. "I wish I were a young boy, wandering idly, or lying in a wood of larches with the wind stirring the tops of them. There is joy in the slanting stoop of the sea-hawk, but a man builds weariness for himself!"

He went to the door and looked forth.

The Wood of the Ridge stood blackly against the dawn. There was a great stillness. The earth seemed to listen. Suddenly the wood was full of singing voices. A brightness moved in it low down; brightness that grew, and grew; and neared; milk-white. The Hound! The Hound, Failinis, at last!

He broke, glittering, from the wood, and came with great leaps to the Gubbaun. The Gubbaun put his two hands about the head of the Hound.

"Treasure," he cried. "Swift-footed Jewel! Bringer of good tidings! It is time now to pile up the fires of welcome. It is time now to set my house in order. A hundred thousand welcomes!"

The Hound lay down by the door-stone.

The Gubbaun strewed green scented boughs on his threshold, plumes of the larch, branches of ash and quicken. Thorn in blossom he strewed; and marsh-mint; and frocken; and odorous red pine. He wondered if it was for Aunya–or for a stranger.

The Gubbaun piled up a fire of welcome. Beneath it he put nine sacred stones taken from the cavern of the Dragon of the Winds. He laid hazel-wood on the pile for wisdom; and oak for enduring prosperity; and black-thorn boughs to win favour of the stars. Quicken wood he had; and ancient yew; and silver-branched holly. Ash, he had, too, on the pile; and thorn; and wood of the apple-tree. These things of worth he had on the pile. With incantations and ceremonies he built it, and with rites such as Druids use in the hill-fires that welcome the Spring and the coming of the Gods of Dana.

The Gubbaun set out the riches of his house; the beaten metals; the wild-beast skins; the broidered work. "If it is

"I AM HRUT OF THE MANY SHAPES, THE SON OF SRUTH, THE SON OF SRU."

Page 115

Aunya," thought he, "and her mind matches my own, she will care more for wide skiey spaces than for any roof-tree shaped by a tool." He thought of a wide stone-scattered plain; of great wings in the night–and his eyes changed colour. The Gubbaun had every colour in his eyes: they were gray at times like the twilight; green like the winter dawn; amber like bog-water in sunlight.

The Gubbaun considered the riches of his house. He looked at the walls he had built; the secret contrivances, the strange cunning engines he had fashioned. "I was bought," he said to himself, "with a handful of tools! Yet to make–and break–and remake–that is the strong-handed choice."

Outside, joyously, rose the baying of the Hound. They were coming! The Gubbaun set fire a-leap in the piled-up wood and ran to meet them.

Flames licked out; flames that were azure; and orange; and sapphire; and blinding white. They lifted themselves like crowned serpents. They hissed. They danced. They leaped into the air. They spread themselves. They blossomed. They found voice. They sang.

"Have you looked on a fire hotter or stronger than this?" asked the Gubbaun of the girl.

She looked on the flame. She said: "The Wind from the South has more warmth and more strength than all the ceremonial fires in Erin." And as she said it, her eyes that were blue like hyacinths in Spring turned gray like lake-water in shadow.

"It is Aunya," thought the Gubbaun, "she has the wisdom of the hills: I wonder has she the wisdom of the hearth."

He took her by the hand, he showed her his finest buildings; his engines; his secret contrivances. "What is your word on these?" he asked.

"You need no word," said the girl, "and well you know it! When the full tide is full, it is full; to-day, and to-morrow no less. Tear stone from stone of these walls in the hope to surpass them–you can do no more than raise them again, fitting each block to its fellow. Trust your own wit on your work, for it's a pity of him that trusts a woman!"

"You are Aunya," cried the Gubbaun, "you are Aunya, the treasure I lost in my youth. You were a dream in my mind when every precious stone was my covering. A hundred thousand welcomes, Aunya! This house is yours, and all its riches yours! The hearth-flame yours! The roof-tree yours!"

"The reddest sun-rise," said Aunya, "is the soonest quenched. You will bid me go from this house one day, without looking backwards to it. All I ask against that day is your oath to let me carry my choice of three arm-loads of treasure out of this house."

"There is no day in all the days of the year that you will get a hard word from me, Aunya, for now my Tree of Life is the holly: no wind of misfortune can blow the leaves from it."

"Bind your oath on my asking," said Aunya.

Then said the Gubbaun:

"On the strong Sun I bind my oath,

My oath to Aunya:

If I deny three treasure-loads to her,

May the strong Sun avenge her.

On the wise Moon I bind my oath,

My oath to Aunya:

If I rue my oath

Let the wise Moon give judgment.

On the kind Earth I bind my oath,

My oath to Aunya.

On the stones of the field;

On running water;

On growing grass.

Let the tusked boar avenge it!

Let the horned stag avenge it!

Let the piast of the waters avenge it!

On the strong Sun I bind my oath."

"It is enough, my Treasure and my Jewel of Wisdom!" said Aunya.

So Aunya, daughter of the Gubbaun Saor, came home.

HOW THE GUBBAUN

QUARRELED WITH AUNYA,

AND WHAT CAME OF IT

HOW THE GUBBAUN QUARRELED WITH AUNYA AND WHAT CAME OF IT

![[illuminated capital] F with knotwork beast](F.png) OR every stroke of work the Gubbaun did before Aunya came into the house, he did four or five strokes after that. His mind swarmed and buzzed with ideas. His feet were too slow for him. His hands that had the skill of the world in them were but two hands after all–he needed a hundred! He broke himself up with the strength and fire that was in him, as the earth breaks up after long winter.

OR every stroke of work the Gubbaun did before Aunya came into the house, he did four or five strokes after that. His mind swarmed and buzzed with ideas. His feet were too slow for him. His hands that had the skill of the world in them were but two hands after all–he needed a hundred! He broke himself up with the strength and fire that was in him, as the earth breaks up after long winter.

The Son of the Gubbaun made new songs every day: his mind was like a pool that holds a star in it, his life was like a stream that slips away singing.

Day after day kindled itself on the hearth of the sky and burned itself to embers there: and no day took anything from Aunya, and no day wearied the Son of the Gubbaun Saor, but the Gubbaun himself was like an otter that swims among salmon when his jaws are too weary to bite.

Oftentimes Aunya told him a thing before he knew it himself: at times when his mind was hooded she was like a blinding light: at times when he drowsed by the hearth-stone, her eyes made him think of mountain-peaks–chill peaks that climbed against the stars.

She was the goad that urged him beyond himself.

One day he burst out on her:

"You are a parcher of blossoms," he said, "you are the Red Wind from the East: you are a sting in the honeycomb!"

"The wind blows out a little flame," said Aunya, "it fans a big one."

"Go forth from this house," cried the Gubbaun, "you that are a heart-scald and a lessener of strength to me!

Do not come back to this house by day:

Do not come back to it by night:

Do not come back to it by the road:

Do not come back to it through the fields:

Do not come back to it with man, woman, or child in your company.

Do not come back to it alone.

Go forth from this house."

"Give me what you bound your oath on; my three arm-loads of treasure!"

"Take them," said the Gubbaun.

She lifted the cradle with the man-child she had borne in it: she set it outside the

BALOR'S DEVASTATING EYE WAS CLOSE SHUT. HUGELY THE EYELID WEIGHED UPON IT.

Page 118

door. "My first arm-load of treasure in this!"

She lifted her man, the Son of the Gubbaun Saor: she set him outside the door. "My second arm-load of treasure in this!"

She lifted the Gubbaun himself: she set him outside the door. "My third arm-load of treasure in this!”

The Gubbaun hadn't a word out of him.

The Son of the Gubbaun called to the Hound.

"It is time to be going," he said, "the world is wide."

The Gubbaun put his hand on the wall of the house.

"It's farewell now," said he, "to everything that I have made: to the first hearth-flame that I kindled; to the threshold; to the roof-tree–farewell! The world is wide."

"My Treasures," said Aunya, "if ye are set upon wandering the world–so it must be. But there is naught to bar this door on us."

"My Prohibition bars it," said the Gubbaun.

"I can cross the hedge of your Prohibition," said Aunya, "I can pass between the thorns of it, unharmed:

'Do not come back to this house by day.'

I will come back to it by twilight.'Do not come back to it by the road.'

I will come back to it, stepping on the ditches and the walls by the side of the road.'Do not come back to it alone.'

I will come back to it with the Hound, Failinis, that is neither man, woman or child, keeping step for step with me."

"The wind blows out a little flame," said the Gubbaun, "you had the right word, Aunya: it fans a big one!"

HOW THE SON OF THE

GUBBAUN SAOR TALKED WITH

LORDS FROM A STRANGE

COUNTRY

HOW THE SON OF THE GUBBAUN SAOR TALKED WITH LORDS FROM A STRANGE COUNTRY

![[illuminated capital] T flanked by horses](T.png) HE oak-wood in the Gap of the Dragon was Summer-heavy: its branches held a murmurous stillness. Sunshine drowsed in it. The road through the Gap was sun-parched. The Son of the Gubbaun sat by the edge of the wood. He was cutting the ogham of a poem on a stave of holly, and he crooned the verse as he worked. Suddenly a strangling blackness clutched him, a breath as of Winter chilled him. The holly stave dropped from his hands. He rose stumblingly.

HE oak-wood in the Gap of the Dragon was Summer-heavy: its branches held a murmurous stillness. Sunshine drowsed in it. The road through the Gap was sun-parched. The Son of the Gubbaun sat by the edge of the wood. He was cutting the ogham of a poem on a stave of holly, and he crooned the verse as he worked. Suddenly a strangling blackness clutched him, a breath as of Winter chilled him. The holly stave dropped from his hands. He rose stumblingly.

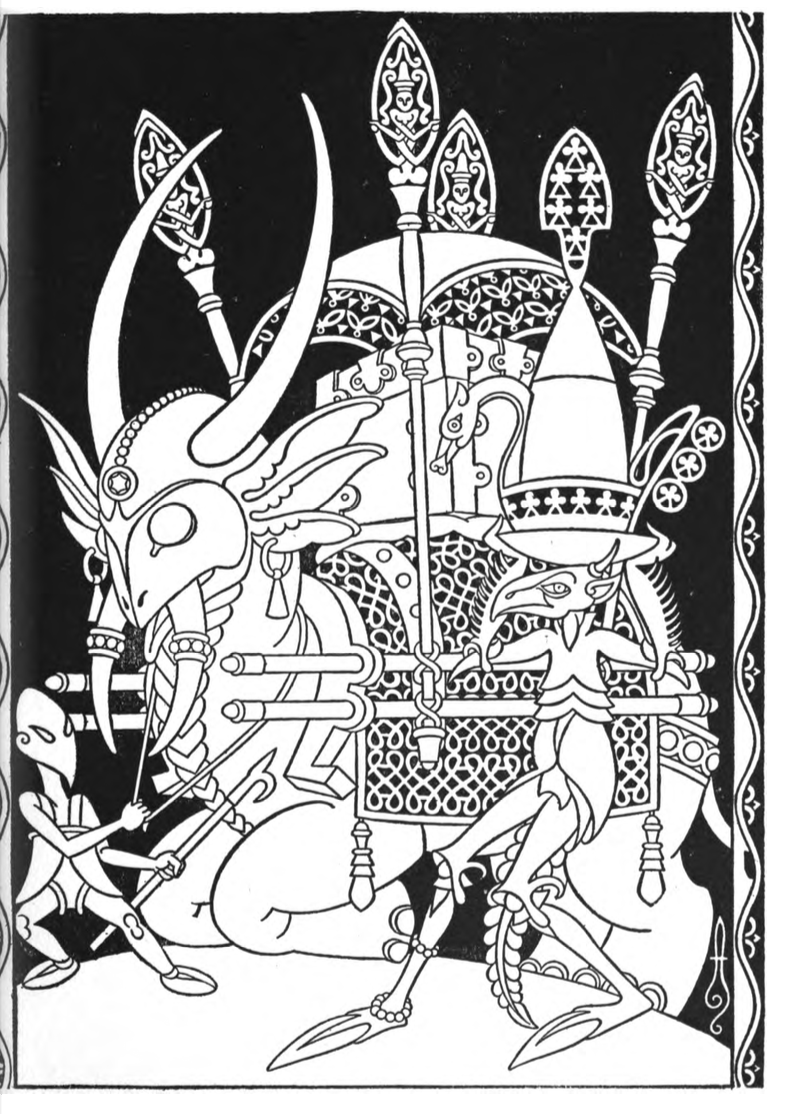

The road through the Gap was filled with strange creatures: monstrous, uncouth animals straddled on it; dwarfs and giants, men that seemed deformed, crowded on it. They were cloaked and hooded. The two that stood nearest to the Son of the Gubbaun had robes that were stiff with gems. Their faces were masked in gold. Their towering head dresses glittered.

"We are come," cried they, "from the Court of Balor of the Mighty Blows, King of the Fomor. A fame and a rumour of the Gubbaun Saor, the Wonder-Smith, has come over the Black Waters into the country of Balor: it has stirred the mind of the king. He would have the Gubbaun build him a dune, a bulk, a rooted vastness that will be a weight upon the earth, a piled-up mountainous strength. To you, O Wonder-Smith, our king sends gifts and tokens. He will not stint the reward."

"You do not speak with the Gubbaun Saor. I am his Son."

"O Son of the Gubbaun Saor, entreat your father for us: of you, too, a rumour has come. Our king bespeaks your countenance and help. Behold the gifts and tokens of Balor!"

Eight slaves blacker than charred wood led forward a pack-bearing beast: a beast to wonder at. He had horns that a bull could not carry: his hide was striped and barred like a tiger's, and a bush of hair, curling in twists, spread on his shoulders. He knelt heavily, and the slaves uncovered a world of riches before the Son of the Gubbaun Saor. They showed him cloths woven of gold and findruiny with patterned dragons coiling in their folds; drinking-cups crusted with gems; daggers hilted with narwhale tooth. The Son of the Gubbaun fingered emeralds as big as the egg of a gull and greener than a field of grass. Deep azure-coloured sapphires slipped through his hands; topazes that were rose-red; rubies like blood; stones very great and precious.

"Choose arles and earnest-money from amongst these," said Balor's messengers, "and at the Black Waters, Balor's folk will await you."

The Son of the Gubbaun chose a ruby, and a stone in which divers colours were spilt. His mind was tangled in the stones for a moment, and when he lifted up his eyes the road was emptiness. The gorgeous train, the fantastic beasts, the lords that had peacocked it, were gone! The sun was hot on his face.

It was with speed and with promptitude and with a fine energy of running that he set out for the house of the Gubbaun. The Gubbaun himself was on the threshold.

"Wonder-Smith," cried the Son, "I have seen a vision though it is not the Eve of Samhain. I have talked with lords from a far country. I have a token for you."

He showed the precious stones and told what had befallen.

"I have worked for many kings," said the Gubbaun, "and was ever the kingliest myself. Balor is a blackener of the earth. He has one eye in the centre of his forehead that can devastate walled cities and blast a country-side. His breath freezes the sea-furrows. Why should I go to the country of Balor?"

"A strange land must Balor's country be," said the Son, "a land of chasms and deserts and icy fastnesses: the beasts of it are not like the beasts of the green earth: the skies have desolate lights in them: the

"A DUNE WITH COURTS AND PASSAGES AND SECRET CHAMBERS."

Page 119

lords of it hide their faces. Strange happenings wait for us in Balor's country. Are you not tired of the roads we know? Is not triumph sweet in an alien land? Let us go to the country of Balor I entreat you."

"Because the green pastures have given you strength and lustihood," said the Gubbaun, "the desert delights you, and the road that dips under the sky-line entices your feet. But since it is so, let us start for the country of Balor with the rising of the sun to-morrow. There is no end to the hunger of the mind."

Before the rising of the sun they rose. The Gubbaun took a gift to the Well of the Hazels. He cut a little rod from the Hazel Tree. He bathed his forehead. But the Son, too eager to start, did none of these things: he was choosing a travelling-cloak.

"May every day delight you till I come back bringing a gift from the Fomor!" he cried to Aunya, and ran out.

The Gubbaun Saor followed.

They had not gone far when the Gubbaun said: "Son, shorten the road for me."

"Put a shape of running on yourself," said the Son, "and your own two feet will shorten it."

"Is that all the road-wisdom you have?" said the Gubbaun.

"It is," said the Son.

"We may as well go back," said the Gubbaun. "It's little help you would be to me in Balor's country."

Home they went. The Gubbaun shut himself up with his engines and secret contrivances, but the Son sat down by the hearth, and the Hound laid a head on his knee. The Gubbaun's Son caressed the Hound and he made a little rann for him. He said:

"Hound

My heart's delight

Moon-white

Sun-bright

Hound from Under-the-Sea

You left a King

To follow me.

And O Hound, and O Hound," said the Gubbaun Saor's Son, "if my wits were as nimble as your feet I wouldn't be sitting here now."

"The Hound drank at dawn from the Sacred Well," said Aunya, "have you returned for a draught?"

"It was a misfortune that brought me back," said the Son. "My father bade me to shorten the road for him. I told him to put a shape of running on himself. He would have none of it. And since I am not a winged demon of the storm, or a gray hawk of the cliffs, I could think only of the swiftness that was in our feet. Back we came on every step we had taken."

"Story-telling," said Aunya, "is the shortening of a road."

"My blessing on the mouth that taught me!" said the Son. "I have tales to last the life-time of a man; tales of scaly dragons and witches of the marshes; tales of deep whirlpools and piasts and spells of enchantment: with these I will shorten the road to-morrow."

On the morrow the Son of the Gubbaun rose in the whiteness of dawn. He put a linen robe on his body. He crowned himself with a chaplet of arbutus that had fruit and blossom. Barefooted he went three times around the Sacred Well, as the sun travels, stepping from East to West. Then he knelt and touched the waters with his forehead and the palms of his hands. He said:

"Well of the Sacred Hazels

Heart of the Hidden Waters

Well of Wisdom

Be a deep coolness in my mind,

Be hidden strength, O Well, in the hour of adversity,

Show me the truth in the hour of deceit.

Nourisher of the Rocks

Life of Waters

Eye that looks on the Stars

Let there be love between us."

Aunya called to him:

"It is time to set out," she said.

"It is not without advice and without a road-blessing that I am setting out," said the Son. "The Well will give me a road-blessing. Give me an advice."

"Whoever you affront where you are going," said Aunya, "put no affront on a woman: for women are the unlockers of secrets, and a woman's hate hunts like the wolf. This is my counsel and I add a gift to it."

She gave him a rod of the hazel.

"It is likely," she said, "that this rod will help you!"

She turned to the Gubbaun.

"It is likely," she said, "that you have such a rod yourself."

"It is more than likely," said the Gubbaun.

They started.

The distance they had gone was not great when the Gubbaun said:

"Son, shorten the road for me."

"Story-telling," said the Son, "is the shortening of a road!"

The oak-wood in the Gap of the Dragon had the redness of Spring on its branches. Midyir's queen came from the Sidhe-mound, lamenting–"

"Is the tale sorrowful?" asked the Gubbaun.

"It is sorrowful in parts, but the joyful parts are stronger than the sorrowful parts: and the end is joyful."

"Continue with it," said the Gubbaun.

The Son continued. He continued till they came to the Black Waters.

THE BUILDING OF

BALOR'S DUNE

THE BUILDING OF BALOR'S DUNE

![[illuminated capital] A flanked by knotwork birds](A.png) T

the edge of the Black Waters two of Balor's lords awaited the Gubbaun and his Son. They were cloaked and hooded and closely masked, yet it seemed to the Son of the Gubbaun that under the hood of one of them there was only half a face, and under the hood of the other the head of some strange animal.

T

the edge of the Black Waters two of Balor's lords awaited the Gubbaun and his Son. They were cloaked and hooded and closely masked, yet it seemed to the Son of the Gubbaun that under the hood of one of them there was only half a face, and under the hood of the other the head of some strange animal.

"Salutation," said the half-faced one, and as he spoke the sea of black waters reared itself in waves. "Salutation to the Wonder-Smith and his Son. I am Hrut of the many shapes, the son of Sruth, the son of Sru, the son of Nar, chief and man of might in the country of Balor–and lo, Balor's boat awaits us!"

Beneath them, huddling against a jagged stairway, a boat lay blackly on the Black Waters. It had neither steersman nor galley-slave, neither sail nor oar. Unmoored it swung blankly like a drowned body cast up by the sea.

Without a word the Gubbaun stepped aboard. The Son followed. The hooded lords took their places. Hrut leaned over the stern. He lifted three handfuls of water and flung them against the sky. He gave a loud, piercing, horrible cry.

At that a sea-demon put his shoulder to the boat. He lifted the sea in a curved black foam-smoking precipice in front of the prow–he left it a gaping hollow behind! Short was their crossing.

Harsh was their welcome in Balor's country. A hard bleak desolate wilderness Balor's country was. The sun never lifted his forehead on it. The moon never showed herself. Every blade of grass in Balor's country was like a knife with a drop of venom on the point of it. The jagged stones were scimitar-edged.

"Will it please you, Wonder-Smith, to walk or ride?" asked Hrut.

"To ride," said the Gubbaun.

Hrut gave a keen piercing cry.

Down THEY swooped out of the air; horribly toothed and clawed, with wings that made a storm about them. Fire came from their nostrils. They bit and clawed one another.

"Will you ride, Wonder-Smith?" asked Hrut.

"I will ride," said the Gubbaun, "put bridles on them."

They put bridles on the biggest one for the Gubbaun, and on the second biggest one for the Son.

"Have you rods," said the Gubbaun, "to encourage them, or to chastise them?"

"They encourage themselves," said Hrut, "No rider has chastised them. Hold fast. As for us we will trust to our feet."

The Gubbaun took a master-grip. The Son copied him. They rose in the air.

"Oh!" cried the Son, "it is nothing I have under me but a slanting icy wind, and that is thinning and spreading away–I am falling!"

"Give your fine steed the rod," said the Gubbaun, "the Hazel rod!"

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor drew a blow on the wind, and with that the scaly-writhing, fire-breathing, feathered monster took shape under him again. It was so till they struck the fastness of Balor.

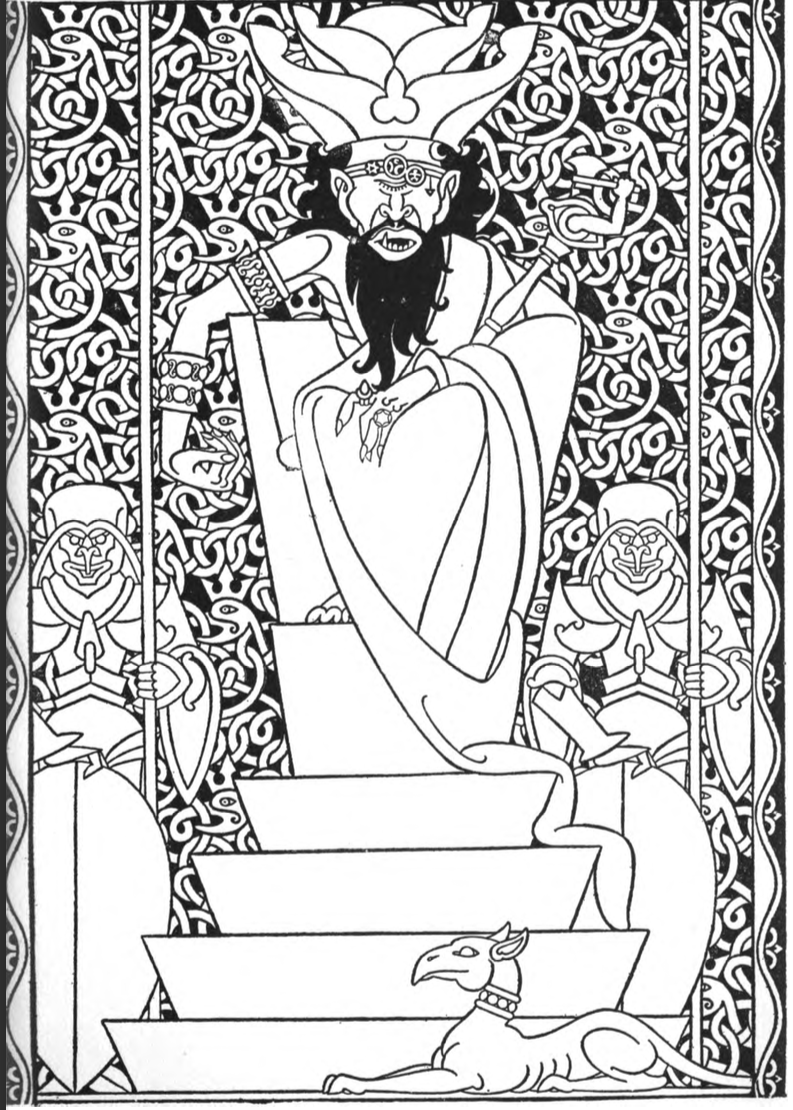

Balor's devastating eye was close shut. Hugely the eyelid weighed upon it, fleshy and sullen. Runes and spells and charms and incantations were on that lid to keep it shut. Balor's face was a blankness. His voice whipped the ears like sleet.

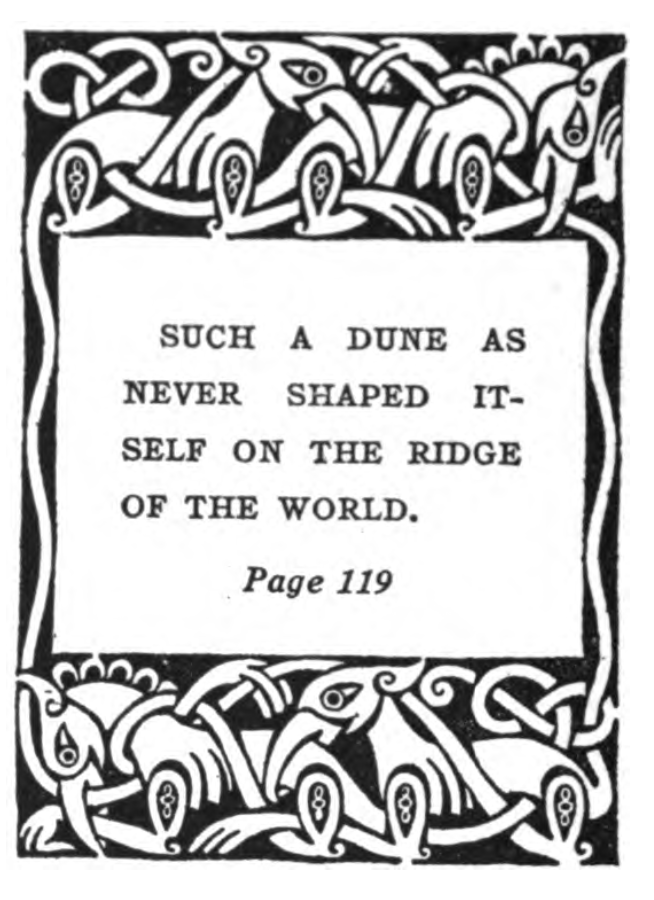

"Build me a dune," he said, "strong as the foundations of the earth; a dune with courts and passages and secret chambers; with carvings on the walls of it and carved monsters in the crevices of it; a dune that climbs and blossoms in spires and twists and flame-like billowing curves and fantasies; such a dune as never from the beginning of days shaped itself on the ridge of the world. Gold ye shall have in plenty, and rich jewels and cloaks of honour. Ye shall stagger under the load of your riches. I, Balor, have said it."

"Such a dune," said the Gubbaun, "I can rear."

The Gubbaun and his Son set to work. They had djinns, and dwarfs, and giants, and goat-footed men, and demons of the air, and fabulous animals, and monstrous beings, and strange beasts to help them. The dune took shape, it grew. There was great delight on the Son of the Gubbaun. He wished with all his heart for a reed flute, but Balor's country was bare of reeds. At length he fashioned a flute of metal, and as he played on it in an idle hour, a woman of Fomor drew close to him. She was poor. She had known hardship. Wrapped in her mantle she held a young child. It was a little while before she spoke. She said:

"For my little son I pray your good will with the music you make. There is a wasting sickness on him and he has no delight in life."

"I will make a Music of Delight for him," said the Gubbaun's Son.

The child put his mother's cloak away from him and peered out. His face was dusky; he had prick ears like a faun; his hair was a black tangled bush standing up

"WYE-HOO! WYE-HOO! WYE-HOO! BAL-A-LOO! BAL-A-LOO! AI! AI! AI!"

Page 147

on his head; his eyes were golden-yellow and very bright, like the eyes a goat has. His eyes pleased the Son of the Gubbaun Saor.

"I will play Strength and Joy," he said.

Every day after that the Son of the Gubbaun made music for the Fomor woman and her child. He played away the sickness. He played till the child laughed and danced and tumbled over himself with delight. One day the woman was troubled.

"You have given life and delight to my child," she said. "To-day he can repay you. My son has one gift from his birth–he can hear the stir of a bird's wing at the other end of the world! No walls can shut a whisper from him: and he has heard a whisper about you. Balor will put you and your father to death when ye have made an end of building the dune, lest a dune the like of it be reared for another. Take counsel therefore with what wisdom is in you and go unharmed from this country."

The Son of the Gubbaun took that news to his father.

"I must think," said the Gubbaun, and he sat down.

The djinns sat down. The goat-footed ones sat down. The fabulous animals stretched themselves and licked their paws. There was a marvellous, munificent, soul-gratifying cessation of labour.

Balor's voice split the stillness.

"Let the Gubbaun come before me," he cried.

The Gubbaun came.

"The work has stopped," roared Balor. "Wherefore?"

"The work has stopped," said the Gubbaun, "because I am short of a tool that is lying under seven locks in my treasure-chest at home."

"Give the tokens and signs of that tool," said Balor, "my swiftest messenger shall speed for it!"

"I trust no hand but my own on the tools of my trade."

"Trust your own hand: my messenger shall bring the treasure-chest."

"The chest is bedded with the foundations of the house: it cannot be moved!"

"If the house holds to the chest," said Balor, "my messenger will haul it hither as a net hauls the dog-fish with the salmon."

He called to one of his most powerful djinns.

"Go," he said, "and bring the treasure-chest of the Wonder-Smith hither, though you should bring the ribs of the earth with it!"

"Live for ever, Magnificence," said the djinn, and was gone.

"He will not come back," said the Gubbaun Saor.

Balor writhed his lips in a scornful smile.

HOW THE DJINN OUT OF

BALOR'S COUNTRY BROUGHT

A MESSAGE TO AUNYA

HOW THE DJINN OUT OF BALOR'S COUNTRY BROUGHT A MESSAGE TO AUNYA

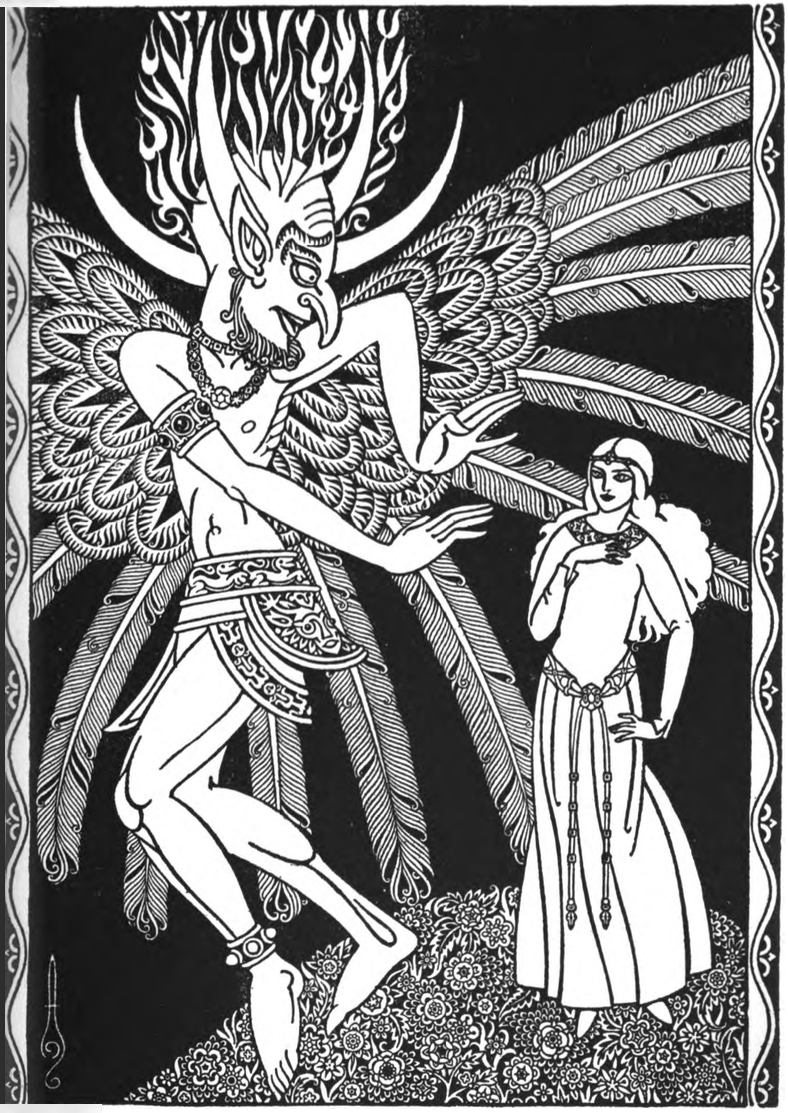

![[illuminated capital] C with standing boy](C.png) LOAKED in gold and vermilion, the sun was stepping into the western sea. The fragrant, amber-coloured air had stillness that was more than music. Aunya stood by the door of the Gubbaun's house. There was stillness and beauty in her face. She watched the sunset. Close to the threshold-stone a furry caterpillar clambered, picking his steps with solemnity and precision. He was a hairy-oubit to delight the heart; his skin was like powdered velvet of a dusky purple colour, his hair-tufts carmined and dusted with silver. His head, like an ebon mirror, gave back the sunlight.

LOAKED in gold and vermilion, the sun was stepping into the western sea. The fragrant, amber-coloured air had stillness that was more than music. Aunya stood by the door of the Gubbaun's house. There was stillness and beauty in her face. She watched the sunset. Close to the threshold-stone a furry caterpillar clambered, picking his steps with solemnity and precision. He was a hairy-oubit to delight the heart; his skin was like powdered velvet of a dusky purple colour, his hair-tufts carmined and dusted with silver. His head, like an ebon mirror, gave back the sunlight.

Suddenly a murk of blackness caught the sky; blackness, myriad-plumed, multitudinously twisting and gyrating upon itself; a rushing, roaring, monstrous, devouring blackness that neared in leaps, and bounds; and contortions; and cataclysms.

It was Balor's djinn.

Quick as thought, Aunya put a shape of magic power on herself. She made herself a spear-point of light against that blackness. The blackness split on it and passed on either side of the house.

"Messenger of Balor," said Aunya, "you overshot the goal!"

The djinn was angered. He turned: he made himself a raging fire, a tongue of flame against Aunya. He writhed and licked devouringly.

Aunya raised herself in a thunderous-sounding, green, over-toppling wave of the sea. Hiss-s-s-rt!!! The fire was quenched.

The djinn shook himself clear. He rose up, an icy scimitar-edged relentless-smiting wind of the desert. He smote the smoking sea-wave, he ripped it to shreds of foam: he flung himself flat-edged upon it: he leaned his weight in the thrust of an avalanche: his strokes were hammer-blows, his strokes were lightning flashes. He howled outrageously, he tied himself into knots. Aunya made herself a drop of water and slid into the earth. The djinn collected himself and drew breath a moment–the wave had gone, no wetness of it glittered!

"Victory," shouted the djinn. "A great and utter destruction! I have been too strong."

Laughter set his ears on edge. Aunya had taken her own shape again and was standing just out of hand-grip.

The djinn made himself an enormous, death-dealing, sickle-clawed, sabre-toothed, tigerish atrocity, and sprang for her! As he leaped, Aunya became a hawk crested with red gold and feathered with white silver. She hung motionless out of reach. She fluttered moth-like about his head: moth-like she slid between his frantic paws: her talons gripped his shoulder: her wings buffeted him: she tweaked his tail: she pinched his ears: she tickled his nose: she was on both sides of him: she was above him, and below him, and beyond him, all at once. She was everywhere and nowhere.

At last the great beast rolled exhausted, with the foam of fruitless endeavour clogging and bitter in his mouth.

"Victory leans towards me," said Aunya.

"Nay," said the djinn, "we are too evenly matched to contend thus. We waste time. Let us show each to the other in rivalry what power we are masters of. My power will out-bid yours."

"So be it," said Aunya. "Wit is nimble-footed!"

"Cunning is more deep-rooted," said the djinn.

"More to a thick skull suited," said Aunya.

"Strength gives to wit the lie," said the djinn.

"Only while strength is by," said Aunya.

"Strength's claws are sharp and crooked," said the djinn.

"But wit has wings to fly," said Aunya.

"Let's leave this rhyming," said the djinn. "It is fit only for women. Show me a wonder-feat."

"LET US LEAVE THIS RHYMING," SAID THE DJINN. "IT IS FIT ONLY FOR WOMEN. SHOW ME A WONDER-FEAT."

Page 135

"I think," said Aunya, "that tree-splitting would delight you."

"It would," said the djinn.

Close to them was a giant yew-tree. It was older than the oldest ancestor of the eagle: old as the roots of the earth. A tough-knit, mighty-girthed, many-twisted trunk that tree had. Aunya struck it lightly with her hand. The yew-tree split from top to bottom: the redness at its heart was like the redness in a cleft pomegranate.

"Make the tree whole, O djinn," said Aunya.

"I am a Force of Destruction and Ravage," said the djinn; "make it whole yourself!"

Aunya put her hand on the wound–the tree was whole as before.

"Split the tree," said Aunya.

The djinn bent himself to the work. He made himself a flash of lightning–and slid through the leaves of the tree! He made himself a devastating whirlwind–and drew a singing note from the tree! He made himself a toothed weapon–he blunted, he shivered himself–and there was not a scratch on the tree!

"Does it out-task you, Son of Destruction?" asked Aunya.

"I could split a small branch," said the djinn, "if I tried!"

"You have not enough strength,” said Aunya, "to hold two branches apart if you perched in a fork of the tree to get your breath again!”

The djinn made a leap for the tree and sat himself in a fork of it.

"Close! branches," said Aunya.

They closed and nipped the djinn: tighter and tighter they nipped him.

"My grief and my destruction," cried the djinn: "I am lost! Take victory, Aunya, and let me out."

"I will give you room to sit at your ease," said Aunya, "but no more. Sit there till the Gubbaun Saor and his Son come home. When their feet cross the house-threshold I will give you freedom: and more than that, the length of your ears in two gold earrings for luck."

"A swift home-coming to the Gubbaun Saor and his Son!" said the djinn:

"May the Earth hasten their footsteps,

May water smooth the paths for them,

May the wind hustle them forward."

"My own wish," said Aunya: "Sit there: you will see the sunrise: you will see the young crescent moon: you will see the greenness of grass."

She left him.

"I'll put ears on me a mile long," said the djinn to himself as he braced his shoulders in the fork of the bough, and took deliberately and with care the position of greatest ease.

THE EMBASSY OF

BALOR'S SON

THE EMBASSY OF BALOR'S SON

![[illuminated capital] B with birds](B.png) ALOR'S country awaited the return of the djinn. The hours and days went by. A fury of expectancy wasted Balor. The Gubbaun Saor was calm.

ALOR'S country awaited the return of the djinn. The hours and days went by. A fury of expectancy wasted Balor. The Gubbaun Saor was calm.

"'Twould be well for myself and my son to lose no more time," said he; "it would be well for us to set out now, for the bringing back of the tool."

"My dignity would be lessened," said Balor, "if the compulsion of that errand were on you. I will send an embassy: like a conquering potentate, like a royal personage, that Tool shall enter my dominions!"

"To your son alone," said the Gubbaun Saor, "will I give the tokens of my Wonder-Tool: with him shall go the chief Vizier of your kingdom."

"So be it," said Balor; "I will send my son: Powers and Principalities shall accompany him."

The Gubbaun Saor gave the master-word to Balor's son.

"The name of the tool is:

Balor's son said it over, nine times, to himself. He was satisfied then that he had it. He called for his robes of embassy, he marshalled the Powers and Principalities: he arranged their ranks for the White Unicorns and the Kyelins with tufted ears: he saw that the Green Dragons and the Scarlet and Purple Chimaeras were linked with chains of silver. Boastful were his words to the Fomorian Lords: "Candles of Valour," he said, "do not grudge your transcendency to a country ignorant of Balor. Ye shall cast lustre upon it."

With an earth-shaking sound of trumpets, that ranked magnificence set forth.

Day rounded day till its return. Its return was an amazement. A sound of ullagoning went before it.

"Wye-hoo! Wye-hoo! Wye-hoo!

Bal-a-loo! Bal-a-loo!

Ai! Ai! Ai!

Ul-a-loo! Ul-a-loo!

Ul-a-loo!

Kye-u-belick!"

Way-side folk, hearing that lamentation, hastened to prostrate themselves and to cover their faces lest they might see how great lords of the Fomor beat their breasts and tore their hair, casting dust on their foreheads. Like a slow, wounded snake the procession dragged itself onward.

"Wye-hoo! Wye-hoo! Wye-hoo!

Bal-a-loo! Bal-a-loo!

That lamentation filled the courts of Balor. Laggard footsteps followed it. Balor's hand groped spearwards. He could not see the grief-dishevelled lords or the anguished abandonment of their prostrations. He dared not open that solitary, terrible eye!

"Speak!" he thundered.

The Most Distinguished Personage in that distinguished train raised a dust-grimed head.

"O Balor, O Lord of Life," he began, "have pity on us! Misfortune has overwhelmed us: grief eats and gnaws upon us. Your Son, the Light of our Countenances, is in captivity. and the great Vizier likewise. Say the word, O Magnificence, that will rescue them from strait and bitter bondage, and from the terrible country of Ireland–a country where the mind is bewildered: a country where the eyes find no rest: for the earth is a glittering emerald and the sky a blinding sapphire, the sun is a scorching fire and the moon a blistering whiteness. A country where there is no solace for the heart!"

"Cease your lamentations," said Balor, "and tell what has befallen."

"We came, O Dispenser of Fate, to the house of the Gubbaun. The woman of the house received us. The most illustrious and splendid Prince, your Son, recited to her the tokens of the Tool:

SUCH A DUNE AS NEVER SHAPED ITSELF ON THE RIDGE OF THE WORLD.

Page 119

"'True is the token,' said the woman of the house; 'I will unbar the treasury for you and the seven locks of the treasure-chest. Enter, Son of Balor; enter, Vizier of Balor.'

"They entered, but they came not forth. The woman came forth.

"'Go hence,' she said, 'and tell your king that in the treasure-chest of the Gubbaun his son is shut–a grip that will not loosen! With him is the Vizier, fastened down with seven locks. There they will measure time by the heart-beat and the shadow and fraction of a heart-beat till the Gubbaun Saor and his Son cross the threshold-stone of this house: whole and sound as they set out from it.'

"O Balor, O Mountain of Munificence, say the word. Let the Gubbaun Saor and his Son go for their Tool!"

The Most Distinguished Personage prostrated himself afresh.

"Wye-hoo! Wye-hoo! Wye-hoo!" sobbed the Unicorns and Chimaeras.

"Balor," said the Gubbaun, "the lid of my treasure-chest is heavy, the sides of it are straight and narrow. Let me and my son go for the tool."

Balor made a frantic gesture with his hands. "Go!" he cried.

Lords of the Fomor ushered forth the Gubbaun and his Son. Carefully they ushered them, like folk who guard a treasure, yet with an urgency of speed. Soon they stood on the terraced height of Balor's fortress. A sky pale as an ice-field was above their heads: a thousand fathoms below, a river pooled itself blackly. About them towered a wilderness of mountain-peaks; peaks, one-footed, craning upward, blind and insatiable; peaks like contorted monsters, huddled abashed upon themselves; peaks like a gigantic menace, dizzied to the fantasy of a nightmare–arid and hostile.

"Bring steeds for us!" said the Gubbaun.

Hrut, the son of Sruth, the son of Sru, the son of Nar, stepped forward. He flung his voice into the air in a shrill ringing cry–like colour spilt on ice it shivered on those monstrous pinnacles. The sky blackened. The air swirled and eddied to an impact.

Biting, clawing, tangled together, THEY descended.

"Bridle them!" said the Gubbaun.

Lords of the Fomor put bridles on them.

"Health and Prosperity be with you!" said the Gubbaun, his hand on a bridled neck.

"Health and Prosperity!" said the Son.

THEY rose, shaking storm from their wings, cavorting and hurtling, plunging and rearing through the steeps of air.

"Snails!" cried the Gubbaun, "have ye no swiftness?"

It was thus that the Gubbaun Saor and his Son returned to Ireland.

THE

GUBBAUN SAOR'S

FEAST

THE GUBBAUN SAOR'S FEAST

![[illuminated capital] W with kneeling woman](W.png) HEN

the Gubbaun Saor and his Son set foot again in Ireland, the earth was glad at their coming: a Wave in the North reared itself and fell with a sound of clangorous bells and loud-voiced trumpets: a Wave in the East reared itself and fell with a sound of clashing cymbals and shrill-voiced flutes: a Wave in the South reared itself and fell with a sound of sweet singing voices mingling with and overmastering the sound of timpaun and cruit and bell-branch: and all along the islands of the West and the rocky inlets went a singing reedy whisper, "Mananaun! Mananaun!"

HEN

the Gubbaun Saor and his Son set foot again in Ireland, the earth was glad at their coming: a Wave in the North reared itself and fell with a sound of clangorous bells and loud-voiced trumpets: a Wave in the East reared itself and fell with a sound of clashing cymbals and shrill-voiced flutes: a Wave in the South reared itself and fell with a sound of sweet singing voices mingling with and overmastering the sound of timpaun and cruit and bell-branch: and all along the islands of the West and the rocky inlets went a singing reedy whisper, "Mananaun! Mananaun!"

The rhythm of that welcoming music was a pulse of joy in the flowering grasses: the strong oaks knew it: the white bulls of the forest moved to it, tossing their moon-curved horns: it set the sea-hawks sliding down the wind, stooping in circles: it was a hand-clapping and a shout of laughter in the mountain torrents.

"A noble land and a good, is Ireland," said the Gubbaun, "my thousand blessings on it!"

Aunya made a great Feast of Welcome for them. From the four corners of the world folk came to the Feast: some that had praise-mouthed names and a proud lineage, and some that had a virtue in them of such a strange and subtle essence that it escaped a clamorous recognition. Harpers came, and sweet-voiced women, and men of learning. Kings' sons came to it riding upon white stallions with bells and apples of gold on their bridle reins and the tails and manes of the stallions dyed a crimson-purple; the workers in brass and copper, the proud makers of beautiful things came to it, and simple poor folk came with good-will in their hearts.

The Chief-Poet of Ireland came, with thirty princes in his train, a slender dark-visaged man, his hair wound upon and bound with twists of gold, his singing-robe on his shoulders that only the Chief-Poet might wear: curiously wrought it was of the feathers of bright-coloured birds. There was a king from the North, blue-eyed and huge of limb, he that was lord of dragon-prowed ships. There was a queen from the South, a woman that many poets had loved; she had a face radiant and pale like magnolia blossom, and eyes the colour of the sky when dusk enpurples it–and everywhere she was the one Rose of Delight.

And there came from the Faery Hills three Cup-Bearers, clad in raiment redder than carbuncle, so beautiful it was a heart-ache to look upon them. They had unwithering youth: beautiful as the light behind the sea-wave–beautiful as the apple-bough beyond our reach!

Light-hearted and impish, in their companies and multitudes, the Sheeoga came–they the Small Folk of the mountain and the bog-land, the Good People who put mortals astray at the fading of the light: or, mindful of new-querned meal heaped in porringers for them and oblations of sweet milk, conduct wayfarers by sure paths across the marshes and craggy sea-frowning precipices–with laughter the Sheeoga came. They joined hands and danced round the house. Aunya sent them out a silver bowl brimmed with wine. Fast as they emptied it, it filled itself again. From hand to hand, from lip to lip they passed it, dancing–their laughter rang like silver bells about the house.

Within the Gubbaun's house the candles of a king's feast were lighted. The djinn was there–he had measured the length of his ears by the height of the door-lintel. The Great Vizier was there, uncobwebbed of the treasure-chest. Balor's Son was there, splendid in his robes of embassy. The Hound Failinis was there, and a Phoenix-Bird that came out of Tir-nan-oge.

The feast began: it went from lavishness to lavishness, it was jewelled with strangeness, as a daggerhilt is crusted with gems. Towards the close, the Gubbaun raised a great Cup of crystal in his hands. The wine in it shone like a ruby: it was wine of Moy-Mell.

"Drink!" he cried. "Let each one drink to the measure of his thirst: the Cup is a well of plenty, it renews itself."

The Cup went from guest to guest, and each one that held that Marvel in his hands drank to the thing he desired to honour. When the Cup came to Balor's Son he rose up and said:

"To Balor the Munificent, and to the noble dune that is a-building!”

The Cup flew into a thousand splinters. The wine ran down like blood.

"Dragon of Death!" cried Balor's Son, "what evil omen is this?"

"The venom of untruth has shattered the Cup," said the Gubbaun. "Balor's munificence was treachery. But not for this thing shall the Cup be destroyed." He gathered the fragments in his hand. "Let truth make it whole:

Balor plotted my death and the death of my Son when the dune was finished."

"SNAILS!" CRIED THE GUBBAUN, "HAVE YE NO SWIFTNESS?"

Page 156

The Cup became whole in the Gubbaun's hand.

"But," said Balor's Son, "in the presence of the lords and chiefs of the Fomor you named the Tool: you gave the Master-Word."

"I named my Tool," said the Gubbaun.

"The Crooked–against crookedness.

The Twist–against a twist: and

The Twist–against treachery.

That Tool I needed: that Tool my hands can handle now. I drink to the time when Balor will know that gods are not jealous of godhead!"

The Gubbaun drank till not a drop remained in the Cup.

"Tell Balor," he said, "that the envious heart drips poison on its own wounds, but munificence begets munificence. His mind imagined a palace: let him build it–he has the multitudinous centuries for leisure! But this one night is ours for joy and song. Let music sound, and let the jugglers now toss up the glittering balls."

Tulkinna the Peerless One stepped forward. He had nine golden apples and nine feathers of white silver and nine discs of findruiney. He tossed them up: they leaped like a plume of sea-spray, they shone like wind-stirred flame, they whirled like leaves rising and falling. He wove them into patterns. They danced like gauze-winged flies on a summer's eve. They gyrated like motes of dust. They tangled the mind in a web of light and darkness till at last it seemed that Tulkinna was tossing the stars.

Then came a burst of light-hearted music.

The djinn danced with the Phoenix-Bird.

Aunya danced with Balor's Son.

The Chief Vizier danced with a woman out of Tir-nan-oge.

The Gubbaun Saor's Son danced with the queen from the South.

The sun and moon, the stars and constellations, danced to the measure of that dancing. The memory of it was honey in the mind of poets for a thousand years: for a thousand years it was riotous heady mead, it was wine in the veins of warriors–and to this hour it is laughter in the heart of the hills.

HOW THE

GUBBAUN SAOR WENT INTO

THE COUNTRY OF THE

EVER-YOUNG

HOW THE GUBBAUN SAOR WENT INTO THE COUNTRY OF THE EVER-YOUNG

![[illuminated capital] N with knotwork beast](N.png) OT

a wind stirred.

OT

a wind stirred.

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor leaned his elbows on a gray wave-worn rock, and his face on his hands.

The sea lay basking on a slant of ivory sand, spreading and stretching itself like a huge dragon that feels the sun; drawing long breaths, lazily conscious of its own bulk and the strength it had. It was of a wonderful colour, like the sky at dawn, like a lapis-stone bathed in honey.

"Heart of my Life," cried the Son of the Gubbaun Saor, "it is not enough to be blue: if you could see the light filtering through the young leaves in a beechwood–that greenness as of fire, that motion, that pulse of colour, you would not bask so easily. Stir yourself, Heart of my Life!"

The huge bulk of the sea responded with an almost imperceptible gesture: it was as if the dragon winked, or stretched out in lazy supercilious recognition a handful of curved claws and drew them back, as a lazy, friendly cat stretches and withdraws them.

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor laughed, and as he laughed two waves ran in like dancers on tiptoe: they were like butterflies that feign to alight, but rise again fluttering upward, poising themselves, swaying rhythmically: they were light as thistledown in a wind: they were tenuous and curved and delicate like the petal of a rose–against the marvel of that blueness they were of an incredible green.

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor clapped his hands: he cried aloud: "My Love of Loves you are! My Feathered Bird you are! Bright Pulse of Flame you are! My Branch with Silver Blossoms! My One Choice!"

His eyes caressed the sea: he stretched his hands to it, but as he stood breathless with joy, a voice came faintly over the grassy sward to him, a distant voice calling him by name. He turned from the rock and saw that Aunya was coming towards him over the short grass that had so many little purple and white flowers in it, low-growing, close-woven in it. She walked as he had seen her walk on that first day when he came through the wind-swept gap suddenly on the plain with crimson blossoms. Her heavy hair was like spun gold. He thought the time long till he could change words with her. She did not speak till she was close to him.

"You must hasten back," she said; "the House-Father has need of us both."

"Is it a blossoming of luck, or misfortune?" asked the Son.

"I know not," she said. "He slept through the sunrise, he slept through the bright whiteness of the day: 'tis but a little while since he wakened with a great cry–a vision, a portent from beyond the world had come to him: he would have us both together for the telling of it."

Aunya took her husband's hand: she did not need to hasten the home-coming.

The Gubbaun was seated in his carved chair. He had clothed himself as though he would speak with kings. His face was like a mask on one that is dead. He moved his hands feebly, they did not know whether in explanation or entreaty, but he did not speak.

"You had a word for us," said the Son.

"I had the Master-Word," said the Gubbaun. "I had knowledge enough to make a sky of stars. Now it is gone from me."

"You know the talk of the birds," said the Son, "and the talk of the beasts, and the talk of the grasses. Is that not enough?"

"I knew the joy that is in the heart of the sun! I knew the secret of life. Now it is gone."

He said no more. He sat day-long like a stone. He lay night-long like a stone; like a sea-crag when the water ebbs from it. For the length of time the moon takes to broaden and grow slender he was like that: strength ebbed from him.

"My thousand griefs!" cried the Son, "he will die: he will not leave behind him the wisdom of his craft!"

"Go to him," said Aunya, "when day whitens. Ask him what tree is king of the forest. It may be that the brightness of his mind will come back to him: if it comes back, cry out that the Dune of Angus is fallen!"

The Son of the Gubbaun rose early. He kindled a fire with boughs of the blackthorn. He dipped the palms of his hands in clear cold well-water. He wrapped himself in a cloak the colour of an amethyst stone.

He went and stood before the Gubbaun.

"O Wonder-Smith, O Master-Builder," he cried, "The Sun is mirrored in the Sacred Well. What Tree is King of the Forest?"

"I know a Forest," said the Gubbaun,

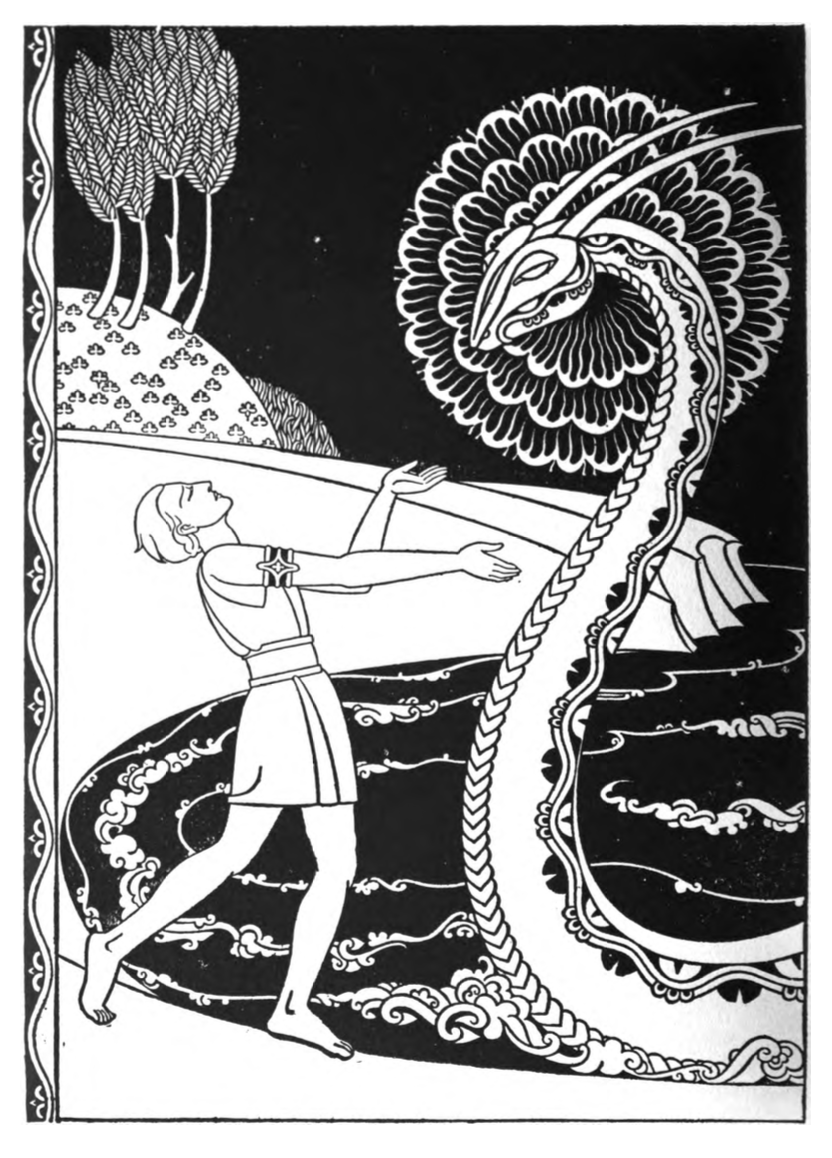

HE SAW THAT IT WAS THE GREAT PIAST HERSELF, DRAWN FOLD ON FOLD FROM THE DEEP.

Page 193

"the roots of it go down deep, deep into the heart of the earth: the branches of it spread among the stars: the stars are fruit upon its branches. The leaves of it make a singing in my mind–singing and sleep."

The Son came forth from the chamber.

"His mind is tangled in dreams," he said.

"Go to him," said Aunya, "when to-morrow whitens."

The Son of the Gubbaun rose early. He kindled a fire with boughs of the yew. He dipped the palms of his hands in clear cold well-water. He wrapped himself in a cloak the colour of embers.

He went and stood before the Gubbaun.

"O Wonder-Smith, O Master-Builder," he cried, "The Moon moves whitely in the Sacred Wood. What Tree is King of the Forest?"

"I know a Forest," said the Gubbaun, "a dark Forest–the leaves of it are days and years, the twisted boughs of it are centuries and millenniums–and I am tangled in its dark and crooked ways: I am caught in its thorny branches: I am lost."

The Son came forth from the chamber.

"His mind is tangled in dreams," he said.

"Go to him," said Aunya, "at the whitening of to-morrow."

The Son of the Gubbaun rose early. He kindled a fire with boughs of the hazel. He dipped the palms of his hands in clear cold well-water. He wrapped himself in a cloak that was spun from threads of white silver and wrought upon with red gold.

He went and stood before the Gubbaun.

"O Wonder-Smith, O Master-builder," he said, "The Sun beholds his image in the Moon. What Tree is King of the Forest?"

The Gubbaun opened his eyes and looked steadily at him.

"Son," he said, "that is soon told. The King of the Forest Trees is the wise gentle Holly."

The Son knew that but a moment remained in which to surprise the secret of his father's craft. He beat his hands together, he beat his forehead, he cried aloud in a voice of lamentation: "Ochone, Ochone, for the Dune of Angus: it is fallen–fallen!"

The Gubbaun raised himself on the bed.

"The Dune of Angus has not fallen," he said, "I built it: it could not fall. It has the strength of rocks. It has the strength of adamant. Storm cannot shake it. It will blunt the teeth of gnawing centuries."

"Tell your Son, O Master-Builder, how you built it. How did you lay the stones of it together?"

"I built it," said the Gubbaun, "with a caid on a caid, a caid over a caid, and a caid between two caids. The Dune of Angus stands!"

"It stands," cried the Son.

The Gubbaun fell back upon the bed, his face was the colour of wax.

"Son," he said, "make a music for me: my hands are done with labour."

The Son of the Gubbaun took up his flute. He played a music from the Faery Hills. Thin and faint at first and of an unearthly sweetness it filled the mind as with a heaven of stars. It had the sound of every instrument and the sound of singing voices in it. Slow rhythms moved through it like sea-waves: light, fierce rhythms leaped like flame: it turned and twisted on itself in intricate mazes and dances of delight. It rose and swelled till it filled the tent of the sky. It slid away into hollows and secret caverns of the earth–chilled and drenched with sweetness. It ebbed and ebbed, withdrawing itself as Cleena's Wave withdraws–a ripple of foam on the void–an echo–a soundless abysm.

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor laid down his flute. No one spoke: but a sudden wind shook the house, and on it there drifted out of a clear sky, petals of snow–white as blossoms shaken from the Silver Branch.

The Gubbaun Saor was dead.

THE GREAT PIAST

![[illuminated capital] T flanked by horses](T.png) HE house of the Gubbaun Saor was so silent that it seemed to listen to itself. Outside there was a sound of multitudinous voices lamenting; thin, reedy voices; sweet, high, singing voices; deep, sorrowful voices; voices like thunderous bells.

HE house of the Gubbaun Saor was so silent that it seemed to listen to itself. Outside there was a sound of multitudinous voices lamenting; thin, reedy voices; sweet, high, singing voices; deep, sorrowful voices; voices like thunderous bells.

The Son of the Gubbaun Saor flung wide the door. He thought at first that the sea had taken the land up to the very threshold. Then he saw that it was the Great Piast herself, drawn fold on fold from the Deep. Writhing and glittering she lay there, scale on scale, and every scale was like a wave that is curved and crested. Like the green light in a sea-hollow was the hooded light about her head.

"O Mighty One, O Piast of the Deep," said the Gubbaun Saor's Son, "why do you lament with so great a lamentation?”

"It is the question," said the Great Piast, "that I came to ask of you."