WOMAN IN LITERATURE.

IN this great review of ours, each company in turn steps to the front, shows its colors, salutes, and passes on to make room for the next. Painters, sculptors, needlewomen, have gone by, and now the woman of letters must raise her banner (sable, a pen rampant by two ink-pots couchant, on a white ground; motto, "Legion!"), must come forward, and give an account of herself.

She is notoriously modest, yet she thinks she has a pretty good account to render, and points with gentle pride to her well-ordered ranks; while, to convince the world of her advance, she refers the public to the literary women of half a century ago, and challenges a comparison. Though she boasts of no higher attainment than her sisters of other professions, yet she may say that she comes of an older family; for woman began to write before she thought of taking prominence in other arts. Was not Anne Bradstreet, wife of Simon the Governor, the first American poet? She died in 1672. She was called the Tenth Muse, and the grim Puritans wept over her poems. One reads them to-day with respect, but feels no keen desire for her Parnassus. Next in order, perhaps, comes Miss Hannah Adams, a gentle and lovely soul, who lived into our own century, and, dying, was the first person buried in Mount Auburn. The family of Sedgwick gives us two writers in the same generation, though one of them held the name by marriage only, having been a Livingston by birth. This latter was Susan, author of several novels and tales, of which one, "Walter Thornly," was written when she was over seventy years of age. Better known than this persevering lady was her sister-in-law, Miss Catherine Sedgwick, whose moral tales attained a wide popularity. She might be called the American Miss Edgeworth, and some of her titles, "The Poor Rich Man and the Rich Poor Man," "Means and Ends," etc., remind us forcibly of that sprightly moralist.

Next we must mention Mrs. Sigourney, a writer of wide repute, though little read to-day. "Pocahontas and Other Poems," "Lays of the Heart," "Tales in Prose and Verse," the very titles breathe of bygone days and thoughts; yet Mrs. Sigourney was a noble and

WALL HANGING REPRESENTING THE GODDESS BONOMIE.

FIGURE BY BURNE-JONES, BELONGING TO THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF ART NEEDLEWORK.

ENGLAND.

lovely woman, and one might spend an hour much less profitably than in making or renewing acquaintance with her writings.

In looking back at these early lights, we must not forget the Davidson sisters, Lucretia and Margaret, that lovely pair whose story was so touchingly and beautifully told by Washington Irving. It is a sad little story of too early development, hectic beauty and blossoming, and death by consumption almost before womanhood was attained. Lucretia, poor child, wrote 278 poems, and died at seventeen. Margaret's record is scarcely less startling and painful.

LOUIS XV. TABLE.

DECORATIONS BY MME. G. NIETER.

FRANCE.

PORTFOLIO CONTAINING PORTRAITS OF DISTINGUISHED

SWEDISH WOMEN.

One wishes they might have lived to-day, and have had some chance of rounding out their gentle lives.

Next we have Mrs. Frances Osgood, author of "A Wreath of Flowers from New England," and other volumes of poetry; and, contemporary with her, the commanding figure of Margaret Fuller. It would be pleasant to dwell at some length on the life of this amazing woman, who began to write Latin verses at eight years old, and whose powers were at their height when the fatal storm of July 16, 1850, hurried her, with all she loved, to her ocean grave; but this brief record can do little more than mention names and dates, and those who do not know Queen Margaret's story are prayed to read it, in Mrs. Howe's memoir of her.

Lydia Maria Child was older than either of the two last-named

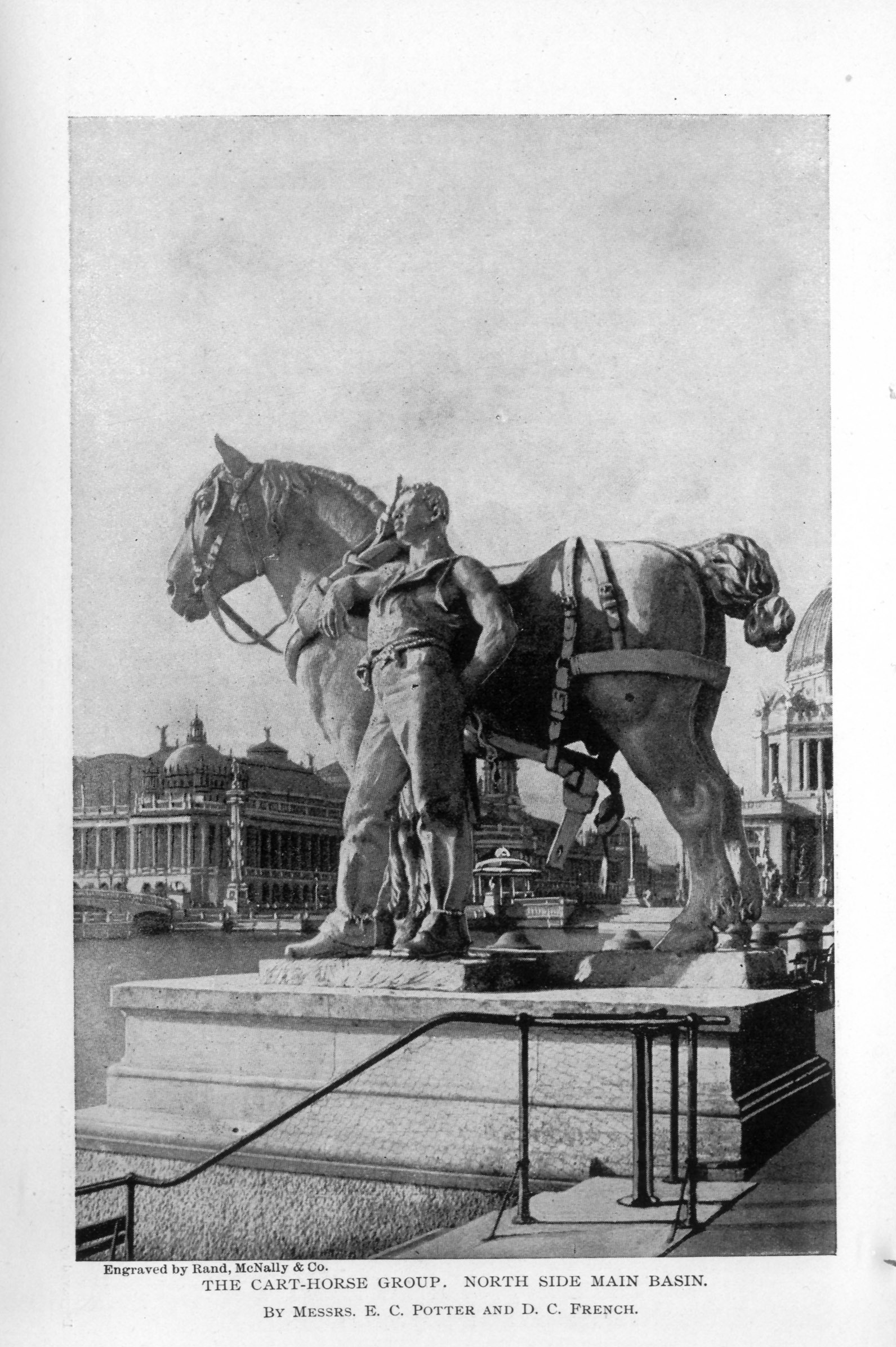

Engraved by Rand, McNally & Co.

THE CART-HORSE GROUP,

NORTH SIDE MAIN BASIN.

BY MESSRS. E. C. POTTER AND D. C. FRENCH.

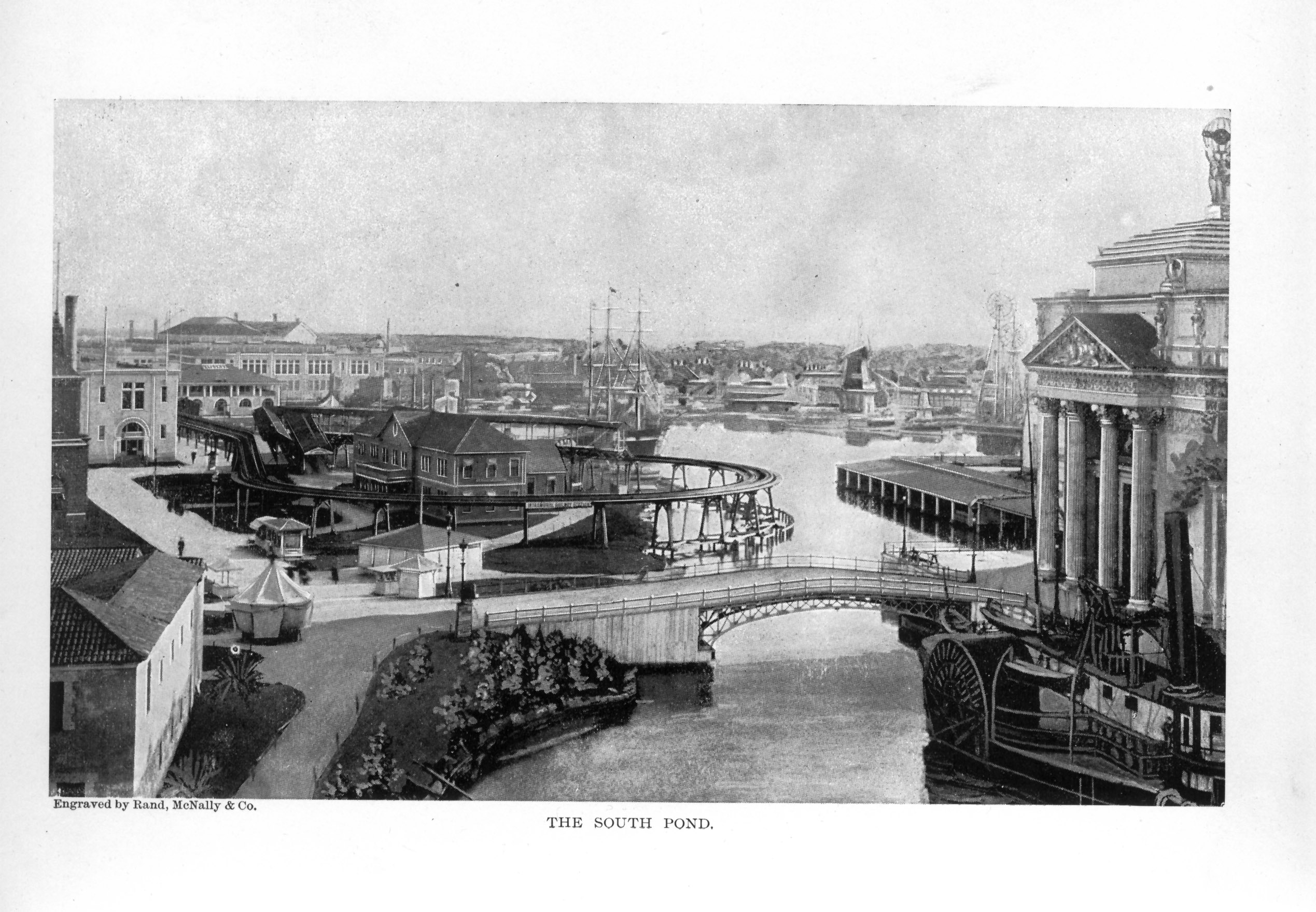

Engraved by Rand, McNally & Co.

THE SOUTH POND.

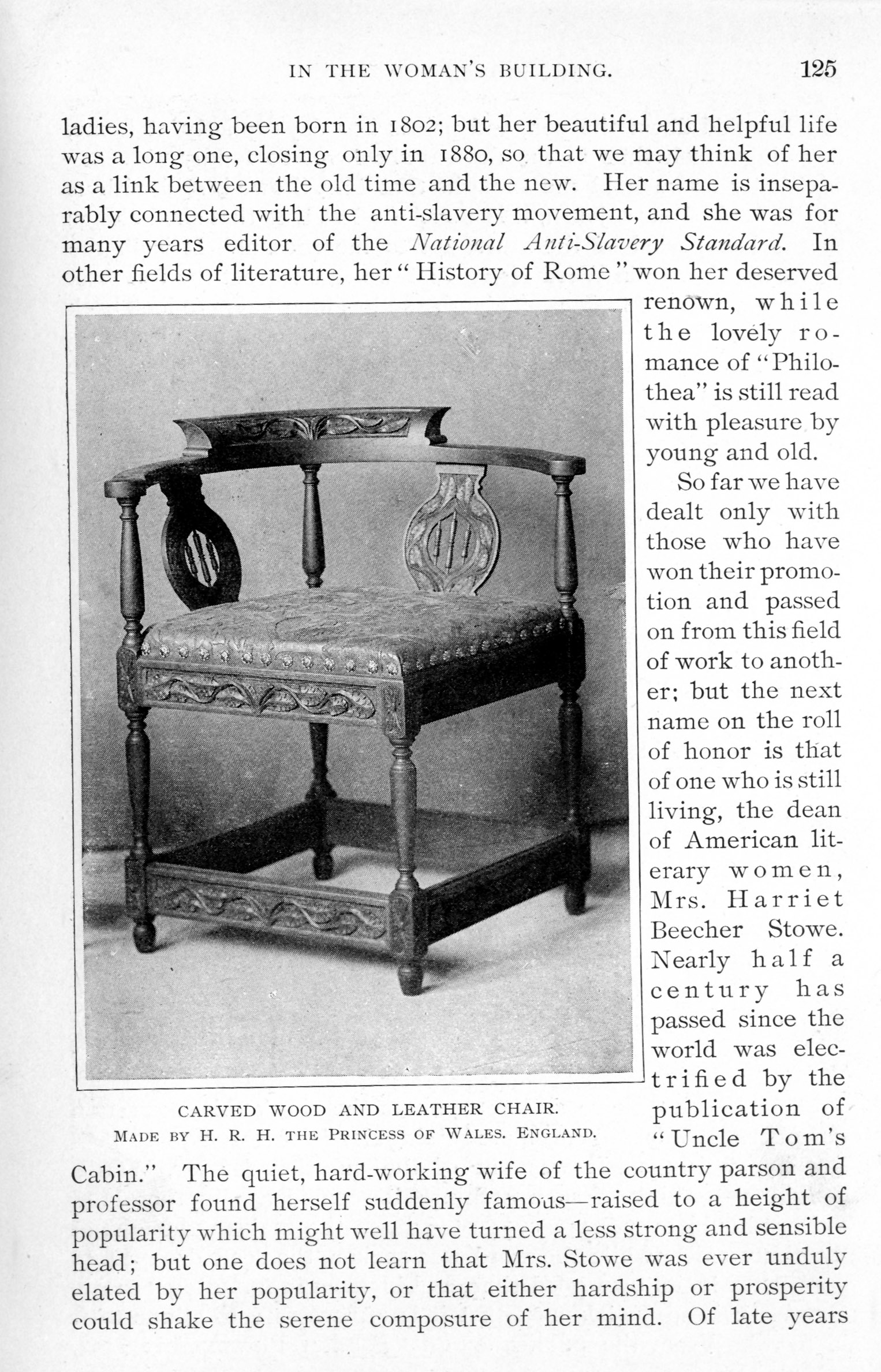

CARVED WOOD AND LEATHER CHAIR.

MADE BY H. R. H. THE PRINCESS OF WALES. ENGLAND.

ladies, having been born in 1802; but her beautiful and helpful life was a long one, closing only in 1880, so that we may think of her as a link between the old time and the new. Her name is inseparably connected with the anti-slavery movement, and she was for many years editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard. In other fields of literature, her "History of Rome" won her deserved renown, while the lovely romance of "Philothea" is still read with pleasure by young and old.

So far we have dealt only with those who have won their promotion and passed on from this field of work to another; but the next name on the roll of honor is that of one who is still living, the dean of American literary women, Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe. Nearly half a century has passed since the world was electrified by the publication of "Uncle Tom's Cabin." The quiet, hard-working wife of the country parson and professor found herself suddenly famous—raised to a height of popularity which might well have turned a less strong and sensible head; but one does not learn that Mrs. Stowe was ever unduly elated by her popularity, or that either hardship or prosperity could shake the serene composure of her mind. Of late years

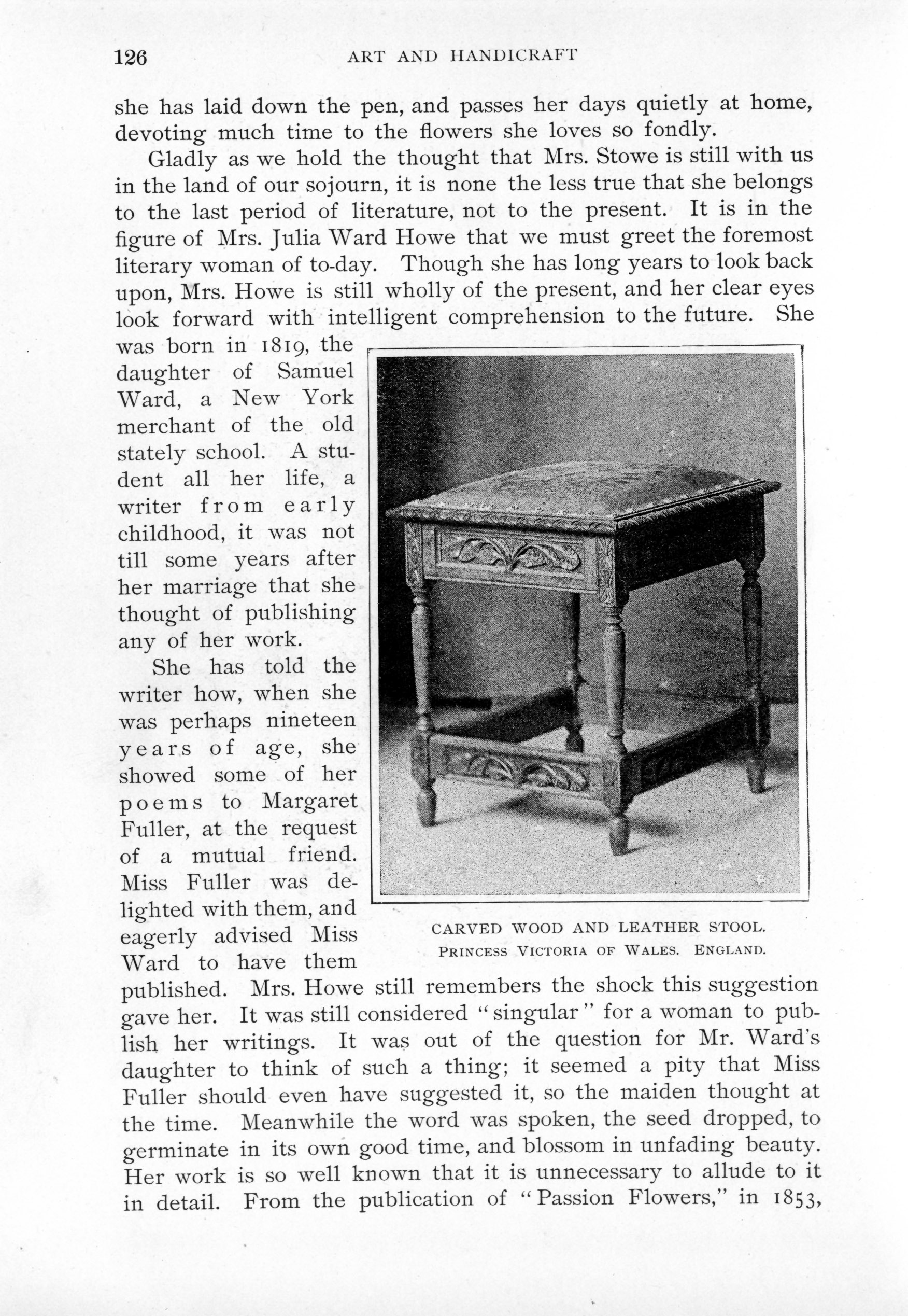

CARVED WOOD AND LEATHER STOOL.

PRINCESS VICTORIA OF WALES. ENGLAND.

she has laid down the pen, and passes her days quietly at home, devoting much time to the flowers she loves so fondly.

Gladly as we hold the thought that Mrs. Stowe is still with us in the land of our sojourn, it is none the less true that she belongs to the last period of literature, not to the present. It is in the figure of Mrs. Julia Ward Howe that we must greet the foremost literary woman of to-day. Though she has long years to look back upon, Mrs. Howe is still wholly of the present, and her clear eyes look forward with intelligent comprehension to the future. She was born in 1819, the daughter of Samuel Ward, a New York merchant of the old stately school. A student all her life, a writer from early childhood, it was not till some years after her marriage that she thought of publishing any of her work.

She has told the writer how, when she was perhaps nineteen years of age, she showed some of her poems to Margaret Fuller, at the request of a mutual friend. Miss Fuller was delighted with them, and eagerly advised Miss Ward to have them published. Mrs. Howe still remembers the shock this suggestion gave her. It was still considered "singular" for a woman to publish her writings. It was out of the question for Mr. Ward's daughter to think of such a thing; it seemed a pity that Miss Fuller should even have suggested it, so the maiden thought at the time. Meanwhile the word was spoken, the seed dropped, to germinate in its own good time, and blossom in unfading beauty. Her work is so well known that it is unnecessary to allude to it in detail. From the publication of "Passion Flowers," in 1853,

SEAT OF STOOL IN LEATHER WORK.

PRINCESS VICTORIA OF WALES. ENGLAND.

down to the present day, her pen has never been idle, her voice never silent in the cause of progress and of practical Christianity. May it be long before we cease to follow the course of that active pen, to listen to that silver voice!

In her own generation Mrs. Howe stands nearly alone among literary women in this country. Fanny Kemble was of her time, and, though not of us, was for so many years with us that we may perhaps place her name upon our roll. Mrs. Kemble's "Records of a Girlhood" and "Records of Later Life" will always be read with delight; and she has also given us some tender and graceful poems. That brilliant and eventful life ended, as is well known, but a few weeks ago. Another contemporary of Mrs. Howe's is Mrs. Edna D. Cheney, whose work will be spoken of later.

First among that great feminine army of translators who trans-

CARVED WOOD AND LEATHER STOOL.

PRINCESS MAUD OF WALES. ENGLAND.

plant the flowers of foreign thought into the garden of our literature, stands Miss Katherine Wormly, whose admirable translations of Balzac have introduced the great French novelist to a new world of readers.

Mrs. James T. Fields has written all too little, to speak from the standpoint of our wishes, yet we have some delightful things from her pen—a volume of poems, "Under the Olives"; "Asphodel," a romance, and the charming reminiscences of famous men, which have appeared from time to time in the magazines, are enough to make us all cry for more; yet we are glad and grateful for these. Mrs. Fields is a prominent figure of literary Boston, and there is no house more delightful than hers.

But now the plot thickens. There came a day when it no longer was singular for women to write. Suddenly it came, one hardly knew how; the windows of the house of Woman were thrown open, and instead of here and there a single lonely watcher on the roof was a crowd of women leaning out, greeting the fresh air with rapture, eager to see, to hear, and more especially to tell. From this moment I drop all attempt at chronological arrangement as invidious, indeed, I can do little more than mention the names that come thronging to my mind. The living must give place to those who have passed from our knowledge.

Helen Hunt, a name beloved by all, has slept for many years beneath her cairn in the West; Emily Dickinson, dying unknown, left us the afterglow of her strange, secluded, seething life. Even as I write, the bells are tolling for the sweet New England poetess

SEAT OF STOOL IN LEATHER WORK.

PRINCESS MAUD OF WALES. ENGLAND.

and noble woman, Lucy Larcom, whose peaceful life has ended peacefully not many months after that of her friend, John Greenleaf Whittier. Her "New England Girlhood" gives us glimpses of a life that it is good to know about, to remember, in these days when luxury and the love of it grow too fast upon us; and some of her poems find an honored place in every anthology of American poets.

How long is it since Louisa Alcott died? four years, or four weeks? Her memory is so fresh in our minds it is hard to realize the flight of time. One seldom sees a fresh copy of her works; they are always read to pieces, thumbed by eager schoolgirls, marked with enthusiastic pencilings, which the guardians of libraries try in vain to prevent. But widely popular as her stories are, we feel that the woman herself was finer than anything she wrote; and the heroic figure pictured so ably and so lovingly in Mrs. Cheney's admirable life of Miss Alcott is but feebly shadowed forth in her own writings.

Mrs. Louise Chandler Moulton has given us several volumes of poems and some charming stories, of which one set in particular,

the "Nightcap" series, is recalled by the writer with tender affection. Mrs. Rebecca Harding Davis has written little of late years, but her powerful novels have won her an enduring place in literature. Miss Constance Fenimore Woolson, to whom we owe the joy of "East Angels," not to be forgotten; Mrs. Whitney, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Gail Hamilton, Celia Thaxter, Harriet Prescott Spofford, Elizabeth Stoddard—this is degenerating into a mere catalogue; but what is a poor scribe to do, who is limited to so many words, and who sees ever new files passing before her, pen in hand, laurel on brow, waving the foolscap banner? I would fain dwell on each of these honored names, but must pass on to others no less worthy of honor. Mrs. Burnett, to whom the crown of the children's love has been given since Miss Alcott laid it down; Mrs. Van Rensselaer, Mrs. Burton Harrison, "Susan Coolidge," Kate Douglas Wiggin, Mary Hallock Foote, and those sweet singers, Edith Thomas and Helen Gray Cone. A step further and we greet Mrs. Deland, "Charles Egbert Craddock," and those three who string jewels on a golden thread, the queens of the short story, Miss Jewett, Miss Wilkins, and Octave Thanet.

Following these come Maud Howe Elliott and Louise Imogen Guiney, Amelie Rives, Agnes Repplier, and Chicago's poetess, Harriet Monroe.

But now I can no more; and I feel as the hostess does who has tried to invite all her acquaintance to an entertainment. If it is only in this last breath that I speak of Mary Hartwell Catherwood and Elizabeth Cavazza; if it is only now that I greet the sweet memory of Emma Lazarus, that flower of Israel—it is not because I honor them less, but because the human brain has limits, while the number of women of letters to-day has none.

Greeting to one and all, and love, and honor; those whom I have left out, sitting at the world's great feast, will not miss the spoonful of victuals that I unwittingly deny them; those of whom I have spoken will pardon the brief and insufficient mention.

And so, roll-call being over, the Literary Brigade shoulders pens, raises the banner once more, and passes on.

LAURA E. RICHARDS.

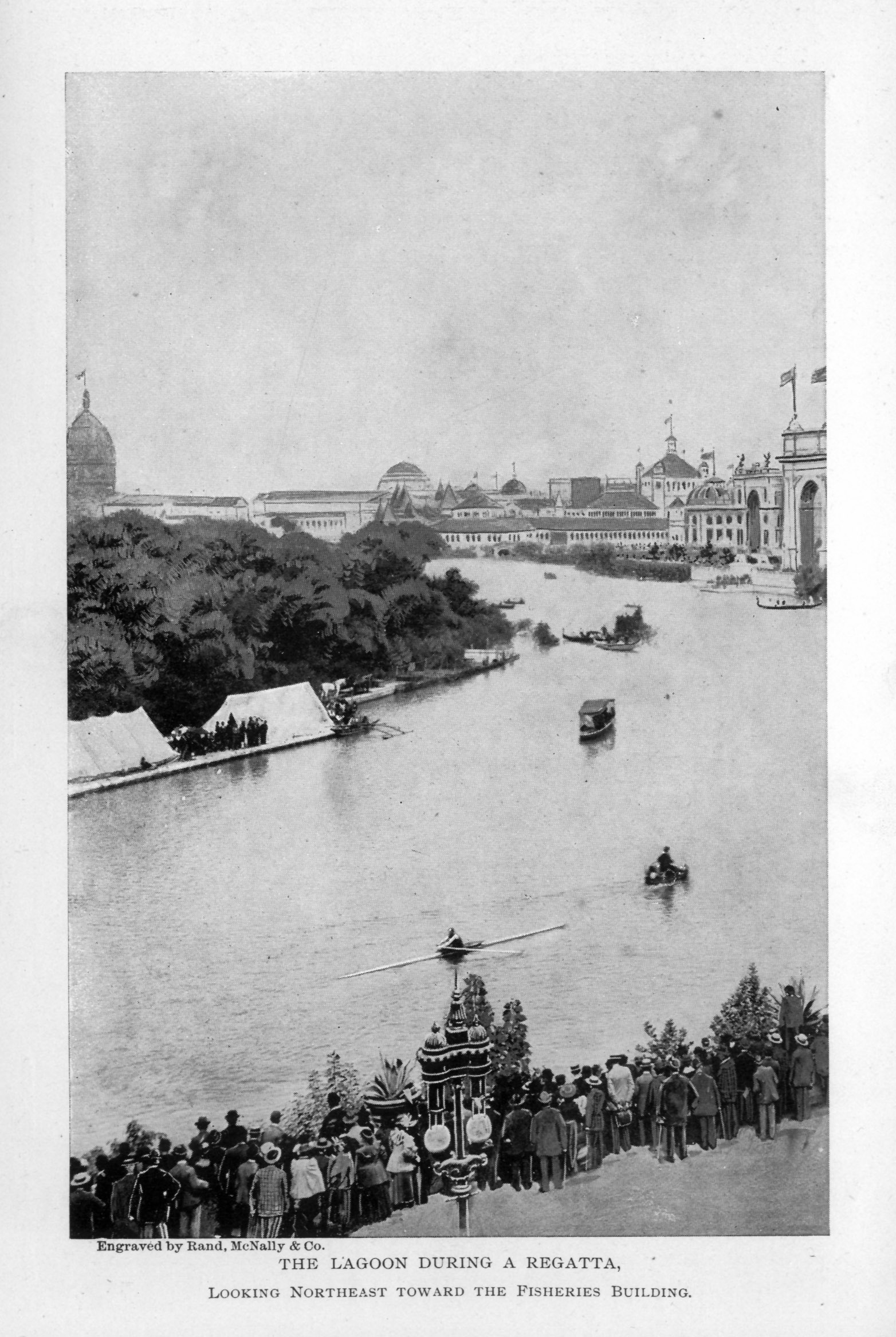

Engraved by Rand, McNally & Co.

THE LAGOON DURING A REGATTA.

LOOKING NORTHEAST TOWARD THE FISHERIES BUILDING.

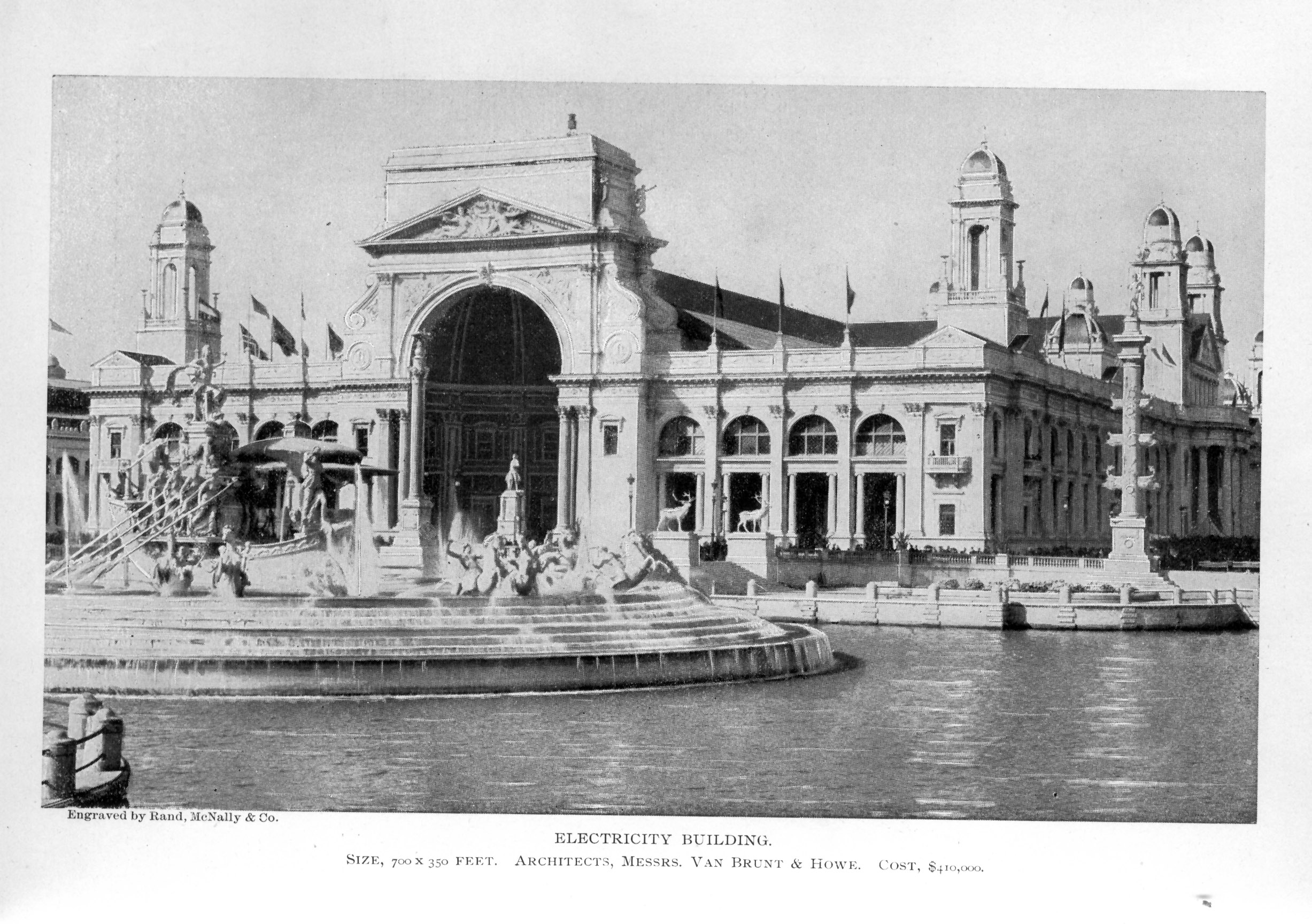

Engraved by Rand, McNally & Co.

ELECTRICITY BUILDING.

SIZE, 700 X 350 FEET. ARCHITECTS, MESSRS. VAN BRUNT & HOWE. COST, $410,000.