GREECE.

SCARCELY sixty years have passed since Greece regained her liberty. During the servile period of her history the status of women was alike precarious and miserable. Man was indeed a slave; but woman was the slave of a slave. So ancient tradition decreed, which even to-day underlies the manners of the Greeks, strengthened by Mussulman influences which have left their impress upon the subjugated generations.

Even now, in the country and the smaller provincial towns, woman is regarded as an inferior being. In the enumeration of his children, the father ignores the females. Women are not privileged to sit at meat with guests; while in the rural districts they are subjected to the .severest labors, cultivating the soil and bowing beneath the weight of grievous burdens of wood and water, brought from a distance. In the villages they remain in-doors, and are seldom seen abroad. In the evening they sit upon their balconies, and on Sunday they offer their prayers within the space reserved for them in the sanctuary. An active participation in affairs is the prerogative of men only, who read the papers, learn the condition of the markets, and make all the purchases for the household.

This rigor is somewhat relaxed in the larger cities, where greater liberty and consideration are accorded to women. Yet even here their tasks are limited to the education of children and the management of domestic affairs. They have no special occupation, no industry to follow, unless it be that of a servant or governess, or perhaps occasionally the trade of a seamstress or modiste, or an operative in one of the few cotton or silk factories.

This degraded condition of Greek women is readily understood, since Greece, during the centuries preceding her proclamation of independence, subject to Turkish rule, and, as it were, isolated from the rest of the world, failed to participate in the great movement of the Renaissance which awakened the civilization of Europe. Roused by her heroic struggle for liberty, she at last recovered the position lost in submission to the yoke of foreign invasion; yet rising from the ruins of her glory, it was necessary, before

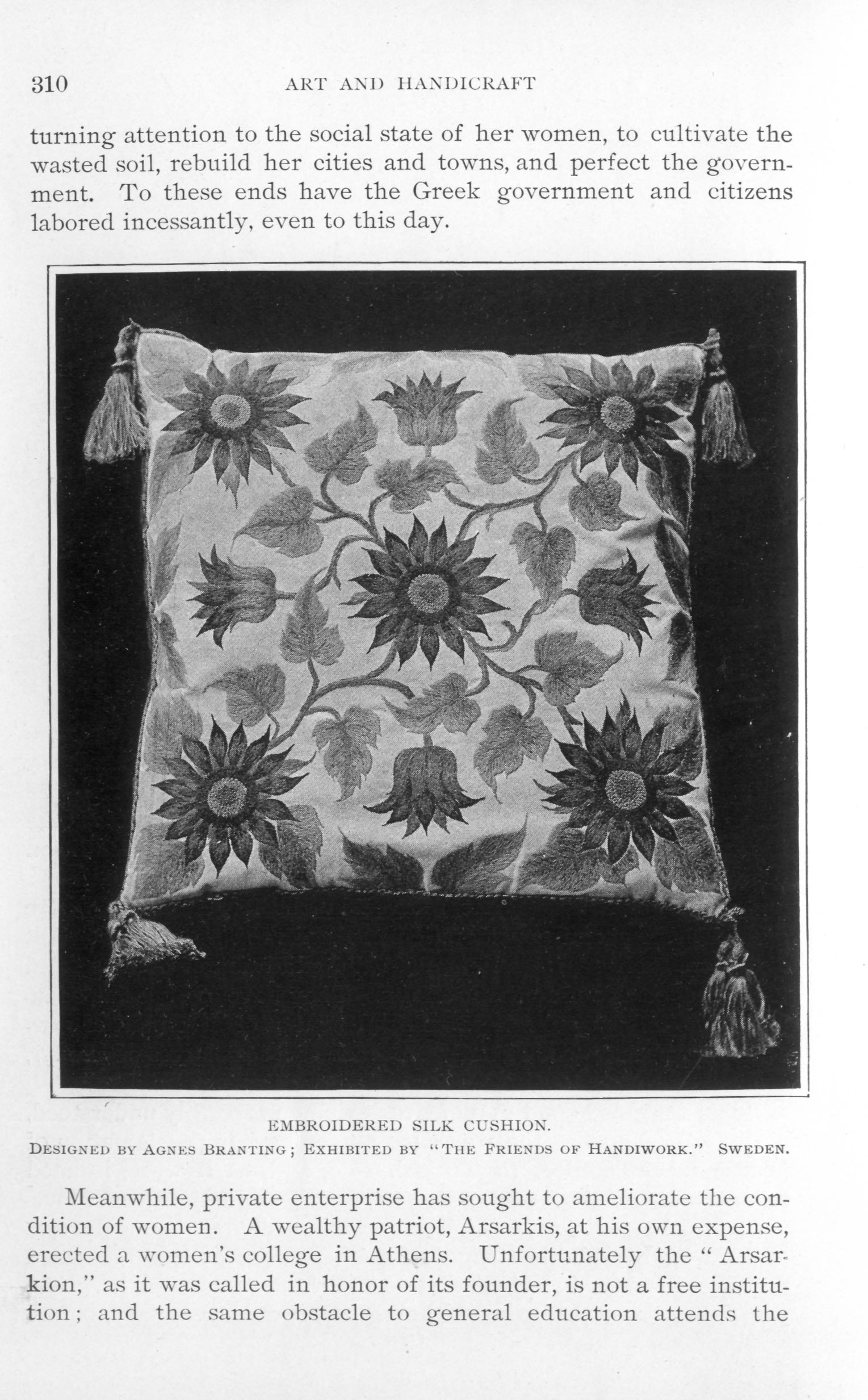

EMBROIDERED SILK CUSHION.

DESIGNED BY AGNES BRANTING; EXHIBITED BY "THE FRIENDS OF HANDIWORK."

SWEDEN.

turning attention to the social state of her women, to cultivate the wasted soil, rebuild her cities and towns, and perfect the government. To these ends have the Greek government and citizens labored incessantly, even to this day.

Meanwhile, private enterprise has sought to ameliorate the condition of women. A wealthy patriot, Arsarkis, at his own expense, erected a women's college in Athens. Unfortunately the "Arsarkion," as it was called in honor of its founder, is not a free institution; and the same obstacle to general education attends the

establishment of three private schools in Athens, which, together with four or five others in the entire kingdom and the "Arsarkion," are the only means afforded to young women of receiving anything more than a primary education.

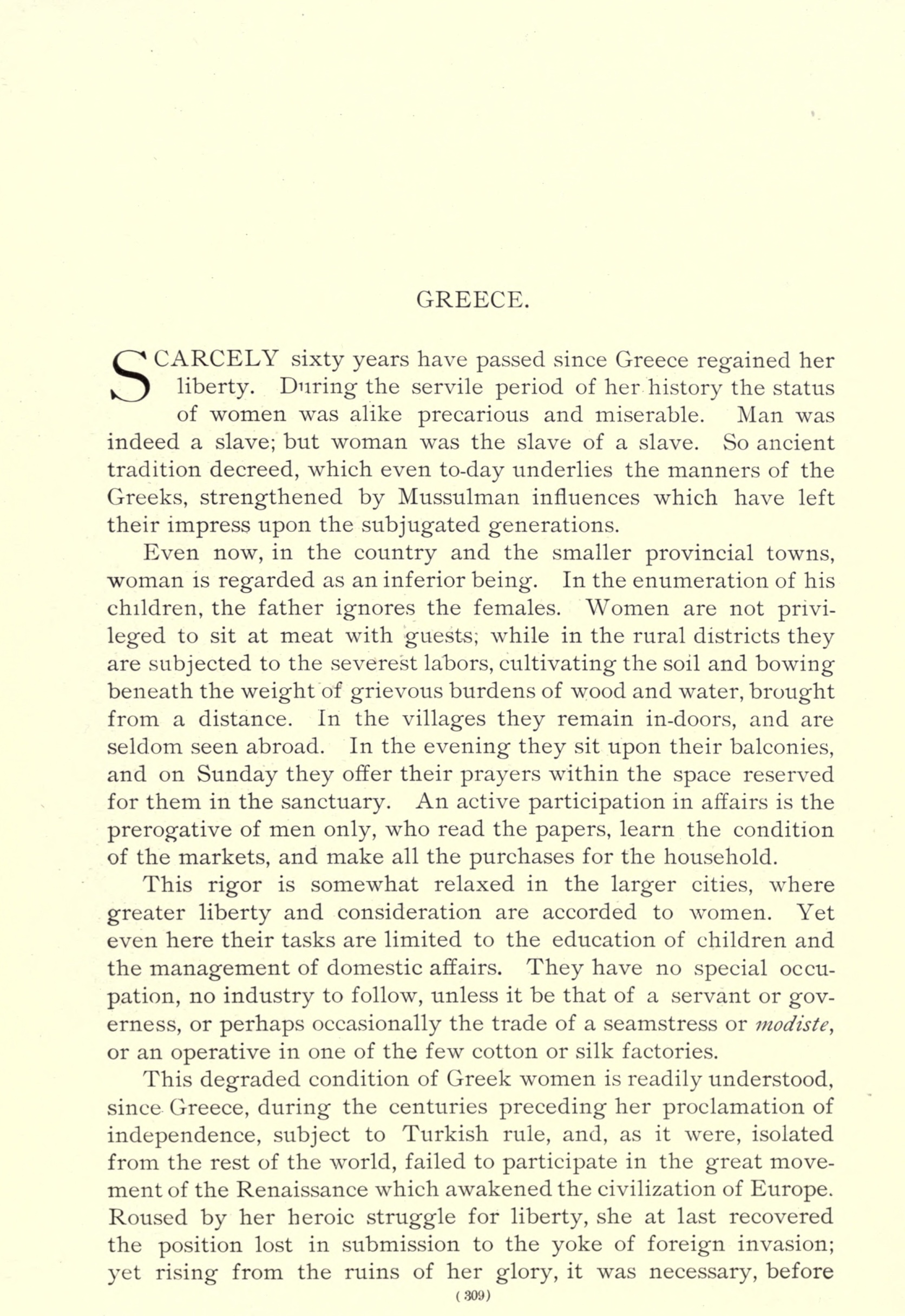

Under such conditions it is easy to understand that art among women is but little developed in Greece, being apparent only in weaving and embroidery. From earliest times the Greek women have spun wool, flax, and silk—as in the Homeric portraiture of Penelope—yet this industry remained comparatively uncultivated until the "Society for the Advancement of Women," under the patronage of Her Majesty Queen Olga, with Madame Skouses as president, established an industrial school for poor women.

This school, where 450 women and girls are employed, has become a source of supply, providing not only the most beautiful models and patterns of weaving and embroidery executed in the style native to the country, but the most exquisite needlework in European fashion.

Moreover, the institution is a philanthropic one, furnishing work for 450 needy women, giving them elementary instruction and providing dinners at a cost of from two to four cents. All labor is piece-work, at prices determined by the superintendent of the society, and all the articles sent to the Exposition are the product of the above institution in Athens.

In the Hellenic provinces women execute similar work. At Tripoli and Leonidi, in the Peloponnesus, and at Arachona and Atlanta, in Locris, carpets are woven; at Kalamata, in Messenia, and at Aghia and Ambelakia, in Thessaly, silk-stuffs are made; at Tripoli, Argos, Missolonghi, and Levadia cotton goods are manufactured; and at Tyrnavo, in Thessaly, printed cottons are prepared. Besides these manufactures, like fabrics are made in almost every home, and in a large proportion of houses we find a loom.

It is in the execution of these textile articles that the taste of the Greek women is displayed. Their work possesses, moreover, a quality of original design and of simplicity, without sacrifice of delicate detail, which augurs favorably for the future development of women's industries in Greece.

MADAME QUELLENEC.