JULIA WARD HOWE

JULIA WARD HOWE

CHAPTER I

EUROPE REVISITED

1877; aet. 58

A MOMENT'S MEDITATION IN COLOGNE CATHEDRAL

|

Enter Life's high cathedral With reverential heart, Its lofty oppositions Matched with divinest art. Thought with its other climbing To meet and blend on high; Man's mortal and immortal Wed for eternity. When noon's high mass is over, Muse in the silent aisles; Wait for the coming vespers In which new promise smiles. When from the dome height echoes An "Ite, missa est," Whisper thy last thanksgiving, Depart, and take thy rest. J. W. H. |

FROM the time of the Doctor's death till her marriage in 1887, the youngest daughter was her mother's companion and yoke-fellow. In all records of travel, of cheer, of merriment, she can say thankfully: "Et ego in Arcadia vixi."

The spring of 1877 found the elder comrade weary with much lecturing and presiding, the younger somewhat out of health. Change of air and scene was prescribed, and the two sailed for Europe early in May.

Throughout the journeyings which followed, our mother had two objects in view: to see her own kind of people, the seekers, the students, the reformers, and their works; and to give Maud the most vivid first impression of all that would be interesting and valuable to her. These objects were not always easy to combine.

After a few days at Chester (where she laments the "restoration" of the fine old oak of the cathedral, "now shining like new, after a boiling in potash") and a glimpse of Hawarden and Warwick, they proceeded to London and took lodgings in Bloomsbury (a quarter of high fashion when she first knew London, now given over to lodgings). Once settled, she lost no time in establishing relations with friends old and new. The Unitarian Association was holding its annual conference; one of the first entries in the Journal tells of her attending the Unitarian breakfast where she spoke about "the poor children and the Sunday schools."

Among her earliest visitors was Charles Stewart Parnell, of whom she says:—

"Mrs. Delia Stewart Parnell, whom I had known in America, had given me a letter of introduction to her son, Charles, who was already conspicuous as an advocate of Home Rule for Ireland. He called upon me and appointed a day when I should go with him to the House of Commons. He came in his brougham and saw me safely deposited in the ladies' gallery. He was then at the outset of his stormy career, and his sister Fanny told me that he had in Parliament but one supporter of his views, 'a man named Biggar.' He certainly had admirers elsewhere, for I remember having met a disciple of his, O'Connor by name, at a 'rout' given by Mrs. Justin McCarthy. I asked this lady if her husband agreed with Mr. Parnell. She replied with warmth, 'Of course; we are all Home Rulers here.'"

"May 26. To Floral Hall concert, where heard Patti — and many others — a good concert. In the evening to Lord Houghton's, where made acquaintance of Augustus Hare, author of 'Memorials of a Quiet Life,' etc., with Mrs. Proctor, Mrs. Singleton [Violet Fane], Dr. and Mrs. Schliemann, and others, among them Edmund Yates. Lord Houghton was most polite and attentive. Robert Browning was there."

Whistler was of the party that evening. His hair was then quite black, and the curious white forelock which he wore combed high like a feather, together with his striking dress, made him one of the most conspicuous figures in the London of that day. Henry Irving came in late: "A rather awkward man, whose performance of 'Hamlet' was much talked of at that time." She met the Schliemanns often, and heard Mrs. Schliemann speak before the Royal Geographical Society, where she made a plea for the modern pronunciation of Greek. In order to help her husband in his work, Mrs. Schliemann told her, she had committed to memory long passages from Homer which proved of great use to him in his researches at Mycenæ and Tiryns.

"May 27.... Met Mr. and Mrs. Wood — he has excavated the ruins at Ephesus, and has found the site of the Temple of Diana. His wife has helped him in his work, and having some practical experience in the use of remedies, she gave much relief to the sick men and women of the country."

"June 2. Westminster Abbey at 2 P.M.... I enjoyed the service, Mendelssohn's 'Hymn of Praise,' Dean Stanley's sermon, and so on, very unusually. Edward Twisleton seemed to come back to me, and so did dear Chev, and a spiritual host of blessed ones who have passed within the veil..."

"June 14. Breakfast with Mr. Gladstone. Grosvenor Gallery with the Seeleys. Prayer meeting at Lady Gainsborough's.

"We were a little early, for Mrs. Gladstone complained that the flowers ordered from her country seat had but just arrived. A daughter of the house proceeded to arrange them. Breakfast was served at two round tables, exactly alike.

"I was glad to find myself seated between the great man and the Greek minister, John Gennadius. The talk ran a good deal upon Hellenics, and I spoke of the influence of the Greek in the formation of the Italian language, to which Mr. Gladstone did not agree. I know that scholars differ on the point, but I still retain the opinion I expressed. I ventured a timid remark regarding the number of Greek derivatives used in our common English speech. Mr. Gladstone said very abruptly, 'How? What? English words derived from Greek?' and almost

"'Frightened Miss Muffet away.'

"He is said to be habitually disputatious, and I thought that this must certainly be the case; for he surely knew better than most people how largely and familiarly we incorporate the words of Plato, Aristotle, and Xenophon in our everyday talk."1

Mr. Gladstone was still playing the first rôle on the stage of London life. Our mother notes hearing him open the discussion that followed Mrs. Schliemann's address before the Royal Geographical Society. Lord Rosebery, who was at that time Mr. Gladstone's private secretary, talked much of his chief, for whom he expressed impassioned devotion. Rosebery, though he must have been a man past thirty at the time, looked a mere boy. His affection for "Uncle Sam" Ward was as loyal as that for his chief, and it was on his account that he paid our mother some attention when she was in London.

She always remembered this visit as one of the most interesting of the many she made to the "province in brick." She was driving three horses abreast, — her own life, Maud's life, the life of London. She often spoke of the great interest of seeing so many different circles of London society; likening it to a layer cake, which a fortunate stranger is able to cut through, enjoying a little of each. Her modest Bloomsbury lodgings were often crowded by the leaders of the world of letters, philanthropy, and art, and some even of the world of fashion. The little lodging-house "slavey" was often awed by the titles on the cards she invariably presented between a work-worn thumb and finger. It is curious to contrast the brief record of these days with that of the Peace Crusade.

"June 10. To morning service at the Foundling Hospital — very touching. To luncheon with M.G.D. where met the George Howards."

"June 15.... 'Robert' [opera] with Richard Mansfield."

"June 18. Synagogue."

"June 19. Lord Mayor's Mansion House. I am to speak there concerning Laura Bridgman. Henry James may come to take me to St. Bart.'s Hospital."

"June 25. 'Messiah.' Miss Bryce."

"June 26. Dined with Capt. Ward. Theatre. Justin McCarthy."

"June 28. Meeting in Lambeth Library."

"June 29. Russell Gurney's garden party.

"Miss Marston's, Onslow Sq., 4 P.M. Anti-vivisection. Met Dudley Campbell. A day of rest, indeed. I wrote out my anti-vivisection argument for to-morrow, and finished the second letter to the Chicago 'Tribune.' Was thus alone nearly all day. Dined at Brentini's in my old fashion, chop, tea, and beer, costing one shilling and fivepence."

She remembered with pleasure an evening spent with the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire at Devonshire House. A ball at Mr. Goschen's was another evening of enchantment, as was also the dinner given for her at Greenwich by Edmund Yates, where she had a good talk with Mr. Mallock, whose "New Republic" was one of the books of that season. She managed, too, sometimes to be at home; among her visitors were William Black, John Richard Green, and Mr. Knowles, editor of the "Nineteenth Century."

The London visit lasted nearly two months; as the engagements multiply, its records grow briefer and briefer. There are many entries like the following:—

"Breakfast with Lord Houghton, where met Lord Granville and M. Waddington, late Minister of Education in France. Garden party at Chiswick in the afternoon. Prince of Wales there with his eldest son, Prince Albert Victor. Mrs. Julian Goldsmith's ball in the evening."

It is remembered that she bravely watched the dancers foot it through the livelong night, and drove home by daylight, with her "poor dancing Maud"!

Madame Waddington was formerly Miss King, the granddaughter of Mr. Ward's old partner. Our mother was always interested in meeting any descendants: of Prime, Ward & King.

With all this, she was writing letters for the Chicago "Tribune" and the "Woman's Journal." This year of 1877 saw the height of the Æsthetic movement. Mrs. Langtry, the "Jersey Lily," was the beauty and toast of the season. Gilbert and Sullivan's "Patience" was the dramatic hit of the year, and "Greenery yallery, Grosvenor Gallery" the most popular catch of the day.

She found it hard to tear herself away from England; the visit (which she likened to one at the house of an adored grandmother) was over all too soon. But July was almost gone; and the two travellers finally left the enchanted island for Holland, recalling Emerson's advice to one going abroad for the first time: "A year for England, and a year for the rest of the world!"

The much neglected Journal now takes up the story.

The great Franz Hals pictures delighted her beyond measure. She always bought the best reproductions she could afford, and valued highly an etching that she owned from his Bohémienne. She never waited for any authority to admire either a work of art or a person. She had much to say about the influence of the Dutch blood both in our own family and in our country, which was to her merely a larger family connection. All through Holland she was constantly noting customs and traditions which we seemed to have inherited; and she felt a great likeness and sympathy between herself and some of the Dutch people she knew.

"The Hague. To the old prison where the instruments of torture are preserved. The prison itself is so dark and bare that to stay therein was a living death. To this was often added the most cruel torture. The poor wretch was stretched on a cross, on which revolving wheels, turned by a crank, agonized and destroyed his spinal column — or, by another machine, his head and feet were drawn in opposite directions — or, his limbs were stretched out and every bone broken with an iron bar. Tortures of fire and water were added. Through all these horrors, I saw the splendors of faith and conscience which illuminated these dungeons, and which enabled frail humanity to bear these inflictions without flinching."

She always wanted to see the torture chambers. She listened to all the detailed explanations and looked at all the dreadful instruments, buoyed up by the thought of the splendors she speaks of, when mere shrinking flesh-and-blood creatures like her companion, who only thought of the poor tortured bodies, could not bear the strain of it.

From The Hague they went to Amsterdam, where they "worked hard at seeing the rich museum, which contains some of the largest and best of Rembrandt's pictures, and much else of interest"; thence to Antwerp. Here she writes:—

"To the Museum, where saw the glorious Rubens and Van Dycks, together with the Quentin Matsys triptych. Went to the Cathedral, and saw the dear Rubens pictures — my Christ in the Elevation of the Cross seemed to me as wonderful as ever. The face asks, 'Why hast thou forsaken me?' but seems also to reflect the answer, from the very countenance of the Father. Education of the Virgin by Rubens — angels hold a garland above the studious head of the young Madonna. This would be a good picture for Vassar."

"Sunday, July 29. Up betimes — to high mass at the Cathedral. Had a seat near the Descent, and saw it better than ever before. Could not see the Elevation so well, but feasted my eyes on both. Went later to the church of St. Paul where Rubens's Flagellation is. Found it very beautiful. At 4 P.M. M. Félu2 came to take us to the Zoo, which is uncommonly good. The collection of beasts from Africa is very rich. They are also successful in raising wild beasts, having two elephants, a tiger, and three giraffes which have been born in the cages — some young lions also. The captive lioness always destroyed her young, and these were saved by being given to a dog to nurse...."

August found the travellers in Prussia.

"Passed the day in Berlin.... At night took railroad for Czerwinsk, travelling second-class. After securing our seats, as we supposed, we left the cars to get some refreshments, when a man and a woman displaced our effects, and took our places. The woman refused to give me my place, and annoyed me by pushing and crowding me."

The brutality of this couple was almost beyond belief. She was always so gracious to fellow-travellers that they usually "made haste to be kind" in return. She made it a point to converse with the intelligent-looking people she met, either in the train or at the tables d'hôte then still in vogue. She talked with these chance acquaintances of their country or their profession. It was never mere idle conversation.

This journey across Europe was undertaken solely for the pleasure of seeing her sister, always her first object in visiting Europe. The bond between them was very strong, spite of the wide difference of their natures and the dissimilarity of their interests. Mrs. Terry was now visiting her eldest daughter, Annie Crawford, married to Baron Eric von Rabé and living at Lesnian in German Poland. Baron Eric had served in the Franco-Prussian War with distinction, had been seriously wounded, and obliged to retire from active service. Here was an entirely new social atmosphere, the most conservative in Europe. Even before the travellers arrived, the shadow of formality had fallen upon them; for Mrs. Terry had written begging that they would arrive by "first-class"! At that time the saying was, "Only princes, Americans, and fools travel first-class," and our mother's rule had been to travel second. The journey was already a great expense, and the added cost seemed to her useless. Accordingly, she bought second-class tickets to a neighboring station and first-class ones from there to Czerwinsk. This entailed turning out in the middle of the night and waiting an hour for the splendid express carrying the stiff and magnificently upholstered first-class carriages, whose red plush seats and cushions were nothing like so comfortable as the old grey, cloth-lined, second-class carriages!

Still, the travellers arrived looking as proud as they could, wearing their best frocks and bonnets. They travelled with the Englishwoman's outfit. "Three suits. Hightum, tightum, and scrub." "Hightum" was for any chance festivity, "tightum" for the table d'hôte, "scrub" for everyday travelling. The question of the three degrees was anxiously discussed on this occasion; it was finally decided that only "hightum" would come up to the Von Rabé standard.

"August 4. Arrived at Czerwinsk, where sister L. and Baron von Rabé met us. He kissed my hand in a courtly manner. My sister looks well, but has had a hard time. We drove to Lesnian where Annie von R. and her mother-in-law made us welcome."

"August 9, Lesnian. A quiet day at home, writing and some work. Tea with Sister L. in the open air. Then went with Baron von Rabé to visit his farm buildings, which are very extensive; not so nicely finished as would be the case in America. We got many fleas in our clothes.... In the evening the Baron began to dispute with me concerning the French and the use and excellence of war, etc...."

"August 12. Up early — to Czerwinsk and thence by Dirschau to Marienburg to see the famous Ritterschloss of the Teutonic Knights.... Marien-Kirch.... Angel Michael weighing the souls, a triptych — the good in right wing received by St. Peter and clothed by angels, the wicked in the other wing going down. The beautiful sheen of the Archangel — like peacock brightness — a devil with butterfly wings."

"August 14. In the church yesterday we were shown five holes in a flat tombstone. They say that a parricide was buried beneath this stone, and the fingers of his hand forced themselves through these holes. They showed us this hand, dried, and hung up in a chapel. Here also we saw a piece of embroidery in fine pearls, formerly belonging to the Catholic service, and worth thousands of dollars. Some very ancient priests' garments, with Arabic designs, were said to have been brought from the East by the Crusaders. An astronomic clock is shown in the church. The man who made it set about making another, but was made blind lest he should do so. By and by, pretending that he must repair or regulate something in the clock, he so puts it out of order that it never goes again.

"The amber-merchant — the felt shoes — views of America — the lecture — the Baltic."

She was enchanted with Dantzig. The ancient Polish Jews in their long cloth gabardines, with their hair dressed in two curls worn in front of the ear and hanging down on either side of the face, showed her how Shylock must have looked. She was far more interested in the relics of the old Polish civilization than in the crude, brand-new Prussian régime which was replacing it; but this did not suit her hosts. The peasants who worked on the estate were all Poles; the relations between them and their employer smacked strongly of serfdom. One very intelligent man, who often drove her, was called Zalinski. It struck her that this man might be related to her friend Lieutenant Zalinski, of the United States Army. She asked him if he had any relatives in America. He replied that a brother of his had gone to America many years before. He seemed deeply interested in the conversation and tried once or twice to renew it. One of the family, who was driving with our mother at the time, managed to prevent any more talk about the American Zalinski, and when the drive was over she was seriously called to account.

"Can you not see that it would be extremely unfortunate if one of our servants should learn that any relative of his could possibly be a friend of one of our guests?"

She was never allowed to see Zalinski again; on inquiring for him, she learned that he had been sent to a fair with horses to sell. He did not return to Lesnian during the remainder of her stay.

One of the picturesque features of the visit was the celebration of Baron Eric's birthday. It was a general holiday, and no work was done on the estate. After breakfast family and guests assembled in front of the old château; the baron, a fine, soldierly-looking man, his wife, the most graceful of women, and the only daughter, a lovely little girl with the well-chiselled Crawford features. The peasants, dressed in their best, assembled in procession in the driveway; one by one, in order of their age or position, they came up the steps, presented the Baroness with a bouquet, bent the knee and kissed the hand of Baron and Baroness. To most of the guests the picture was full of Old-World romance and charm. To one it was an offence. That the granddaughter of her father, the child of her adored sister, should have been placed by fate in this feudal relationship to the men and women by whose labor she lived outraged her democratic soul.

The Journal thus describes the days at Lesnian:—

"The Baron talked much last evening, first about his crops, then about other matters. He believes duelling to be the most efficient agency in promoting a polite state of society. Would kill any one whom he suspected of great wrong much sooner than bring him to justice. The law, he says, is slow and uncertain — the decision of the sword much more effectual. The present Government favors duelling. If he should kill some one in a duel, he would have two months of imprisonment only. He despises the English as a nation of merchants. The old German knights seem to be his models. With these barbarous opinions, he seems to be personally an amiable and estimable man. Despises University education, in whose course he might have come in contact with the son of a carpenter, or small shopkeeper — he himself went to a Gymnase, with sons of gentlemen...."

"Everything in the Junkerschaft3 bristles for another war. Oscar von Rabé's room, in which I now write, contains only books of military drill.

"This day we visited the schoolhouse — session over, air of the room perfectly fetid. Schoolmaster, whom we did not see, a Pole — his sister could speak no German. Tattered primers in German. Visited the Jew, who keeps the only shop in Lesnian. Found a regular country assortment. He very civil. Gasthaus opposite, a shanty, with a beer-glass, coffee-cup and saucer rudely painted on its whitewashed boards. Shoemaker in a damp hovel, with mahogany furniture, quite handsome. He made me a salaam with both hands raised to his head."

"We went to call upon Herr von Rohr, at Schenskowkhan — an extensive estate. I had put on my Cheney silk and my bonnet as a great parade. Our host showed us his house, his books and engravings — he has several etchings by Rembrandt. Herr von Mechlenberg, public librarian of Königsberg, a learned little old man, trotted round with us. We had coffee and waffles. Mechlenberg considers the German tongue a very ancient one, an original language, not patched up like French and English, of native dialects mingled with Latin."

In one of her letters to the Chicago "Tribune" is a significant passage written from Lesnian:—

"Having seen in one of the Dantzig papers the announcement that a certain Professor Blank would soon deliver a lecture upon America, showing the folly of headlong emigration thither and the ill fortune which many have wrought for themselves thereby, one of us remarked to a Dantziger that in such a lecture many untruths would probably be uttered. Our friend replied, with a self-gratulatory laugh, 'Ah, Madame! We Germans know all about the women of America. A German woman is devoted to her household, its care and management; but the American women all force their husbands to live in hotels in order that they may have no trouble in housekeeping.'"

She was as sensitive to criticism of her country as some people are to criticism of their friends. Throughout her stay in Germany she suffered from the captious and provoking tone of the Prussian press about things American.

Even in the churches she met this note of unfriendliness. She took the trouble to transcribe in her Journal an absurd newspaper story.

"An American Woman of Business

"Some little time since, a man living near Niagara Falls had the misfortune to fall from the bridge leading to Goat's Island. [Berlin paper says Grat Island.] He was immediately hurried to the edge of the fearful precipice. Here, he was able to cling to a ledge of rock, and to support himself for half an hour, until his unavoidable fate overtook him. A compassionate and excited multitude rushed to the shore, and into the house, where the unhappy wife was forced to behold the death struggle of her husband, lost beyond all rescue, this spot yielding the best view of the scene of horror. The 'excellent' wife had too much coolness to allow this opportunity of making money to escape her, but collected from every person present one dollar for window rent. (Berliner Fremdenblatt, Sunday, August 26, 1877.)"

The stab was from a two-edged sword; she loved profoundly the great German writers and composers. She was ever conscious of the debt she owed to Germany's poets, philosophers, and musicians. Goethe had been one of her earliest sources of inspiration, Kant her guide through many troublous years; Beethoven was like some great friend whose hand had led her along the heights, when her feet were bleeding from the stones of the valley. These were the Germans she knew; her Germany was theirs. Now she came in contact with this new Junker Germany, this harsh, military, unlovely country where Bismarck was the ruling spirit, and Von Moltke the idol of the hour. It was a rough awakening for one who had lived in the gentler Fatherland of Schiller and of Schubert.

"August 31, Berlin. Up early, and with carriage to see the review.... A great military display. The Emperor punctual at 10. 'Guten Morgen!' shouted the troops when he came. The Crown Princess on horseback with a blue badge, Hussar cap. The kettle-drum man had his reins hitched, one on either foot, guiding his horse in this way, and beating his drums with both hands...."

The Crown Princess, later the Empress Frederick, daughter of Queen Victoria, and mother of the present German Emperor, was the honorary colonel of the hussar regiment whose uniform she wore, with the addition of a plain black riding-skirt. Civilization owes this lady a debt that cannot be paid save in grateful remembrance. During the Franco-Prussian War she frequently telegraphed to the German officers commanding in France, urging them to spare the works of art in the conquered country. Through her efforts the studios of Rosa Bonheur and other famous painters escaped destruction.

The early part of September was spent in Switzerland. Chamounix filled the travellers with delight. They walked up the Brevant, rode to the Mer de Glace on muleback. The great feature, however, of this visit to Switzerland was the Geneva Congress, called by Mrs. Josephine Butler to protest against the legalizing of vice in England.

"At the Congress to-day — spoke in French.... I spoke of the two sides, active and passive, of human nature, and of the tendency of the education given to women to exaggerate the passive side of their character, whereby they easily fall victims to temptation. Spoke of the exercise of the intellectual faculties as correcting these tendencies — education of women in America — progress made. Coeducation and the worthier relations it induces between young men and women. Said, where society thinks little of women, it teaches them to think little of themselves. Said of marriage, that Milton's doctrine, 'He for God only, she for God in him,' was partial and unjust. 'Ce Dieu, il faut le mettre entre les deux, de manière que chacun des deux appartienne premièrement à Dieu, puis tous les deux l'un à l'autre.'"

"Wish to take up what Blank said to-day of the superiority of man. Woman being created second. That is no mark of inferiority. Shall say, this doctrine of inequality very dangerous. Inferior position, inferior education, legal status, etc. Doctrine of morality quite opposite. If wife patient and husband not, wife superior — if wife chaste, husband not, wife superior. Each indispensable to each other, and to the whole. Gentlemen, where would you have been if we had not cradled and tended you?"

"Congress.... Just before the end of the meeting Mr. Stuart came to me and said that Mrs. Butler wished me to speak for five minutes. After some hesitation I said that I would try. Felt much annoyed at being asked so late. Went up to the platform and did pretty well in French. The audience applauded, laughing a little at some points. In fact, my little speech was a decided success with the French-speaking part of the audience. Two or three Englishwomen who understood very little of it found fault with me for occasioning laughter. To the banquet...."

"September 23. This morning Mrs. Sheldon Ames and her brother came to ask whether I would go to Germany on a special mission. Miss Bolte also wished me to go to Baden Baden to see the Empress of Germany."

"September 24. A conference of Swiss and English women at 11 A.M. A sister of John Stuart Mill spoke, like the other English ladies, in very bad French. 'Nous femmes' said she repeatedly. She seemed a good woman, but travelled far from the subject of the meeting, which was the work to be done to carry out what the Congress had suggested. Mrs. Blank, of Bristol, read a paper in the worst French I ever heard. 'Ouvrager' for 'travailler' was one of her mistakes."

In spite of some slight criticisms on the management of this Congress, she was heart and soul in sympathy with its object; and until the last day of her life, never ceased to battle for the higher morality which at all costs protests against the legalizing of vice.

Before leaving Geneva she writes:—

"To Ferney in omnibus. The little church with its inscription 'Deo erexit Voltaire,' and the date.... I remember visiting Ferney with dear Chev; remember that he did not wish me to see the model [of Madame Du Châtelet's monument] lest it should give me gloomy thoughts about my condition — she died in childbirth, and the design represents her with her infant bursting the tomb."

October found the travellers in Paris, the elder still intent on affairs of study and reform, the younger grasping eagerly at each new wonder or beauty.

There were meetings of the Academy of Fine Arts, the Institute of France, the Court of Assizes: teachers' meetings, too, and dinners with deaconesses (whom she found a pleasant combination of cheerfulness and gravity), and with friends who took her to the theatre.

"To Palais de Justice. Court of Assizes — a young man to be condemned for an offence against a girl of ten or twelve, and then to be tried for attempt to kill his brother and brother-in-law....

"We were obliged to leave before the conclusion of the trial, but learned that its duration was short, ending in a verdict of guilty, and sentence of death. In the days that followed our thoughts often visited this unfortunate man in his cell, so young, apparently without friends — his nearest relatives giving evidence against him, and, in fact, bringing the suit that cost his life. It seems less than Mosaic justice to put a man to death for a murder which, though attempted, was not actually committed. A life for a life is the old doctrine. This is a life for an attempt upon a life."

An essay on Paris, written soon after, recalls further memories. She visited the French Parliament, and was surprised at the noise and excitement which prevailed.

"The presiding officer agitates his bell again and again, to no purpose. He constantly cries, in piteous tone: 'Gentlemen, a little silence, if you please.'"

She tells how "one of the ushers with great pride pointed out Victor Hugo in his seat," and says further:

"I have seen this venerable man of letters several times, — once in his own house.... We were first shown into an anteroom, and presently into a small drawing-room. The venerable viscount kissed my hand...with the courtesy belonging to other times. He was of middle height, reasonably stout. His eyes were dark and expressive, and his hair and beard were snow-white. Several guests were present.... Victor Hugo seated himself alone upon a sofa, and talked to no one. While the rest of the company kept up a desultory conversation, a servant announced M. Louis Blanc, and our expectations were raised only to be immediately lowered, for at this announcement Victor Hugo arose and withdrew into another room, from which we were able to hear the two voices in earnest conversation...."

"November 27. Packing to leave Paris to-night for Turin. The blanks left in my diary do not mark idle days. I have been exceedingly busy.... have written at least five newspaper letters, and some other correspondence. Grieved this morning over the time wasted at shop windows, in desiring foolish articles which I could not afford to buy, especially diamonds, which I do not need for my way of life. Yet I have had more good from my stay in Paris than this empty Journal would indicate. Have seen many earnest men and women — have delivered a lecture in French — have started a club of English and American women students, for which Deo gratias! Farewell, dear Paris, God keep and save thee!"

She mentions this club in the "Reminiscences." "I found in Paris a number of young women, students of art and medicine, who appeared to lead very isolated lives and to have little or no acquaintance with one another. The need of a point of social union for these young people appearing to me very great, I invited a few of them to meet me at my lodgings. After some discussion we succeeded in organizing a small club, which, I am told, still exists.... [If we are not mistaken, this small club was a mustard seed which in time grew into the goodly tree of the American Girls' Club.] I was invited several times to speak while in Paris.... I spoke in French without notes.... Before leaving Paris I was invited to take part in a congress of woman's rights. It was deemed proper to elect two presidents for this occasion, and I had the honor of being chosen as one of them....

"Somewhat in contrast with these sober doings was a ball given by the artist Healy at his residence. I had told Mrs. Healy in jest that I should insist upon dancing with her husband. Soon after my entrance she said to me, 'Mrs. Howe, your quadrille is ready for you. See what company you are to have.' I looked and beheld General Grant and M. Gambetta, who led out Mrs. Grant, while her husband had Mrs. Healy for his partner in the quadrille of honor.... Marshal MacMahon was at this time President of the French Republic. I attended an evening reception given by him in honor of General and Mrs. Grant. Our host was supposed to be at the head of the Bonapartist faction, and I heard some rumors of an intended coup d'état which should bring back imperialism and place Plon-Plon [the nickname for Prince Napoleon] on the throne.... I remember Marshal MacMahon as a man of medium height, with no very distinguishing feature. He was dressed in uniform and wore many decorations."

During this visit to Paris, our mother consorted largely with the men and women she had met at the Geneva Congress. She takes leave of Paris with these words: "Better than the filled trunk and empty purse, which usually mark a return from Paris, will be a full heart and a hand clasping across the water another hand pure and resolute as itself."

The two comrades journeyed southward by way of Turin, Milan, and Verona. Of the last place the Journal says:—

"Busy in Verona — first, amphitheatre, with its numerous cells, those of the wild beasts wholesomely lighted and aired, those of the prisoners, dark and noisome and often without light of any kind.... Then to the tombs of the Scaligers — grim and beautiful. Can Signoria who killed his brother was the last. Can Grande, Dante's host."

In Verona she was full of visions of the great poet whose exile she describes in the poem called, "The Price of the Divina Commedia." One who met her there remembers the extraordinary vividness of her impressions. It was as if she had seen and talked with Dante, had heard from his own lips how hard it was to eat the salt and go up and down the stairs of others.

From Verona to Venice, thence to Bologna. Venice was an old friend always revisited with delight. Bologna was new to her; here she found traces of the notable women of its past. In the University she was shown the recitation room where the beautiful female professor of anatomy is said to have given her lectures from behind a curtain, in order that the students' attention should not be distracted from her words of wisdom by her beauty. In the picture gallery she found out the work of Elisabetta Sirani, one of the good painters of the Bolognese school.

And now, after twenty-seven years, her road led once more to Rome.

CHAPTER II

A ROMAN WINTER

1878-1879; aet. 59-60

JANUARY 9, 1878

|

A voice of sorrow shakes the solemn pines Within the borders of the Apennines; A sombre vision veils the evening red, A shuddering whisper says: the King is dead. Low lies he near the throne That strange desert and fortune made his own; And at his life's completion, from his birth In one fair record, men recount his worth. Chief of the Vatican! Heir of the Peter who his Lord denied, Not of the faith which that offence might hide, Boast not, "I live, while he is coldly laid." Say rather, in the jostling mortal race He first doth look on the All-father's face. Life's triple crown absolvèd weareth he, Clear Past, sad Present, fond Futurity. J. W. H. |

THE travellers arrived in Rome in good time for the Christmas dinner at Palazzo Odescalchi, where they found the Terrys and Marion Crawford. On December 31 our mother writes:—

"The last day of a year whose beginning found me full of work and fatigue. Beginning for me in a Western railway car, it ends in a Roman palace — a long stretch of travel lying between. Let me here record that this year has brought me much good and pleasure, as well as some regrets. My European tour was undertaken for dear Maud's sake. It took me away from the dear ones at home, and from opportunities of work which I should have prized highly. I was President of the Woman's Congress, and to be absent not only from its meeting, but also from its preparatory work, caused me great regret. On the other hand, I saw delightful people in England, and have seen, besides the old remembered delights, many places which I never visited before.... I am now with my dear sister, around whom the shadows of existence deepen. I am glad to be with her; though I can do so little for her, she is doing very much for me."

This was a season of extraordinary interest to one who had always loved Italy and pleaded for a generous policy toward her. Early in January it became known that King Victor Emanuel was dying. At the Vatican his life-long adversary Pius IX was wasting away with a mortal disease. It was a time of suspense. The two had fought a long and obstinate duel: which of them, people asked, would yield first to the conqueror on the pale horse? There were those among the "Blacks" of Rome who would have denied the last sacrament to the dying King. "No!" said Pio Nono; "he has always been a good Catholic; he shall not die without the sacrament!" On the 9th of January the King died, and "the ransomed land mourned its sovereign as with one heart."4

"January 12. Have just been to see the new King [Umberto I] review the troops, and receive the oath of allegiance from the army. The King's horse was a fine light sorrel — he in full uniform, with light blue trousers. In Piazza del Independenza. We at the American Consulate. Much acclamation and waving of handkerchiefs. Went at 5 in the afternoon to see the dead King lying in state. His body was shown set on an inclined plane, the foreshortening disfigured his poor face dreadfully, making his heavy moustache to look as if it were his eyebrows. Behind him a beautiful ermine canopy reached nearly to the ceiling — below him the crown and sceptre on a cushion. Castellani's beautiful gold crown is to be buried with him."

She says of the funeral:—

"The monarch's remains were borne in a crimson coach of state, drawn by six horses. His own favorite war-horse followed, veiled in crape, the stirrups holding the King's boots and spurs, turned backward. Nobles and servants of great houses in brilliant costumes, bareheaded, carrying in their hands lighted torches of wax.... As the cortège swept by, I dropped my tribute of flowers5..."

"January 19. To Parliament, to see the mutual taking of oaths between the new King and the Parliament. Had difficulty in getting in. Sat on carpeted stair near Mrs. Carson. Queen came at two in the afternoon. Sat in a loggia ornamented with red velvet and gold. Her entrance much applauded. With her the little Prince of Naples,6 her son; the Queen of Portugal, her sister-in-law; and Prince of Portugal, son of the latter. The King entered soon after two — he took the oath standing bareheaded, then signed some record of it. The oath was then administered to Prince Amadeo and Prince de Carignan, then in alphabetical order to the Senate and afterwards to the Deputies."

A month later, Pio Nono laid down the burden of his years. She says of this:—

"Pope Pius IX had reigned too long to be deeply mourned by his spiritual subjects, one of whom remarked in answer to condolence, 'I should think he had lived long enough!"'

The winter passed swift as a dream, though not without anxieties. Roman fever was then the bane of American travellers, and while she herself suffered only from a slight indisposition, Maud was seriously ill. There was no time for her Journal, but some of the impressions of that memorable season are recorded in verse.

|

Sea, sky, and moon-crowned mountain, one fair world, Past, Present, Future, one Eternity. Divine and human and informing soul, The mystic Trine thought never can resolve. |

One of the great pleasures of this Roman visit was the presence of her nephew Francis Marion Crawford. He was then twenty-three years old, and extremely handsome; some people thought him like the famous bas-relief of Antinous at the Villa Albano. The most genial and companionable of men, he devoted himself to his aunt and was her guide to the trattoria where Goethe used to dine, to Tasso's Oak, to the innumerable haunts dedicated to the poets of every age, who have left their impress on the Eternal City.

Our mother always loved acting. Her nearest approach to a professional appearance took place this winter. Madame Ristori was in Rome, and had promised to read at an entertainment in aid of some charity. She chose for her selection the scene from "Maria Stuart" where the unhappy Queen of Scots meets Elizabeth and after a fierce altercation triumphs over her. At the last moment the lady who was to impersonate Elizabeth fell ill. What was to be done? Some one suggested, "Mrs. Howe!" The "Reminiscences" tell how she was "pressed into the service, and how the last rehearsal was held while the musical part of the entertainment was going on. "Madame Ristori made me repeat my part several times, insisting that my manner was too reserved and would make hers appear extravagant. I did my best to conform to her wishes, and the reading was duly applauded."7

Another performance was arranged in which Madame Ristori gave the sleep-walking scene from "Macbeth." The question arose as to who should take the part of the attendant.

"Why not your sister?" said Ristori to Mrs. Terry. "No one could do it better!"

In the spring, the travellers made a short tour in southern Italy. One memory of it is given in the following verses:—

NEAR AMALFI

|

Hurry, hurry, little town, With thy labor up and down. Clang the forge and roll the wheels, Spring the shuttle, twirl the reels. Hunger comes. Every woman with her hand Shares the labor of the land; Every child the burthen bears, And the soil of labor wears. Hunger comes. In the shops of wine and oil For the scanty house of toil; Give just measure, housewife grave, Thrifty shouldst thou be, and brave. Hunger comes. Only here the blind man lags, Here the cripple, clothed with rags. Such a motley Lazarus Shakes his piteous cap at us. Hunger comes. Oh! could Jesus pass this way Ye should have no need to pray. He would go on foot to see All your depths of misery. Succor comes. He would smooth your frowzled hair, He would lay your ulcers bare, He would heal as only can Soul of God in heart of man. Jesus comes. Ah! my Jesus! still thy breath Thrills the world untouched of death. Thy dear doctrine showeth me Here, God's loved humanity Whose kingdom comes. |

The summer was spent in France; in November they sailed for Egypt.

"November 27, Egypt. Land early this morning — a long flat strip at first visible. Then Arabs in a boat came on board. Then began a scene of unparalleled confusion, in the midst of which Cook's Arabian agent found me and got my baggage — helping us all through quietly, and with great saving of trouble.... A drive to see Pompey's Pillar and obelisk. A walk through the bazaar. Heat very oppressive. Delightful drive in the afternoon to the Antonayades garden and villa.... Mr. Antonayades was most hospitable, gave us great bouquets, and a basket of fruit."

"Cairo. Walked out. A woman swung up and down in a box is brown-washing the wall of the hotel. She was drawn up to the top, quite a height, and gradually let down. Her dress was a dirty blue cotton gown, and under that a breech-cloth of dirty sackcloth. We were to have had an audience from the third Princess8 this afternoon, and were nearly dressed for the palace when we were informed that the reception would take place to-morrow, when there will be a general reception, it being the first day of Bairam. Visit on donkey-back to the bazaars, and gallop; sunset most beautiful."

"Up early, and all agog for the palace. I wore my black velvet and all my [few] diamonds, also a white bonnet made by Julia McAllister9 and trimmed with her lace and Miss Irwin's white lilacs. General Stone sent his carriage with sais richly dressed. Reception was at Abdin Palace — row of black eunuchs outside, very grimy in aspect. Only women inside — dresses of bright pink and yellow satin, of orange silk, blue, lilac, white satin. Lady in waiting in blue silk and diamonds. In the hall they made us sit down, and brought us cigarettes in gilt saucers. We took a whiff, then went to the lady in waiting who took us into the room where the three princesses were waiting to receive us. They shook hands with us and made us sit down, seating themselves also. First and second Princesses on a sofa, I at their right in a fauteuil, on my left the third Princess. First in white brocaded satin, pattern very bright, pink flowers with green leaves. Second wore a Worth dress of corn brocade, trimmed with claret velvet; third in blue silk. All in stupendous diamonds. Chibouks brought which reached to the floor. We smoke, I poorly, — mine was badly lighted, — an attendant in satin brought a fresh coal and then the third Princess told me it was all right. Coffee in porcelain cups, the stands all studded with diamonds. Conversation rather awkward. Carried on by myself and the third Princess, who interpreted to the others. Where should we go from Cairo? Up the Nile, in January to Constantinople."

"Achmed took me to see the women dance, in a house where a wedding is soon to take place. Dancing done by a one-eyed woman in purple and gold brocade — house large, but grimy with dirt and neglect. Men all in one room, women in another — several of them one-eyed, the singer blind — only instruments the earthenware drum and castanets worn like rings on the upper joints of the fingers. Arab café — the story-teller, the one-stringed violin...."

"To the ball at the Abdin Palace. The girls looked charmingly. Maud danced all the night. The Khedive10 made me quite a speech. He is a short, thickset man, looking about fifty, with grizzled hair and beard. He wore a fez, Frank dress, and a star on his breast. Tewfik Pasha, his son and heir, was similarly dressed. Consul Farman presented me to both of them. The suite of rooms is very handsome, but this is not the finest of the Khedive's palaces. Did not get home much before four in the morning. In the afternoon had visited the mosque of Sultan Abdul Hassan...."

After Cairo came a trip up the Nile, with all its glories and discomforts. Beiween marvel and marvel she read Herodotus and Mariette Bey assiduously.

"Christmas Day. Cool wind. Native reis of the boat has a brown woollen capote over his blue cotton gown, the hood drawn over his turban. A Christmas service. Rev. Mr. Stovin, English, read the lessons for the day and the litany. We sang 'Nearer, my God, to Thee,' and 'Hark, the herald angels sing.' It was a good little time. My thoughts flew back to Theodore Parker, who loved this [first] hymn, and in whose 'meeting' I first heard it. Upper deck dressed with palms — waiters in their best clothes...."

"To-day visited Assiout, where we arrived soon after ten in the morning. Donkey-ride delightful, visit to the bazaar. Two very nice youths found us out, pupils of the American Mission. One of these said, 'I also am Christianity.' Christian pupils more than one hundred. Several Moslem pupils have embraced Christianity.... This morning had a very sober season, lying awake before dawn, and thinking over this extravagant journey, which threatens to cause me serious embarrassment."

And again:—

"The last day of a year in which I have enjoyed many things, wonderful new sights and impressions, new friends. I have not been able to do much useful work, but hope to do better work hereafter for what this year has shown me. Still, I have spoken four times in public, each time with labor and preparation — and have advocated the causes of woman's education, equal rights and equal laws for men and women. My heart greatly regrets that I have not done better, during these twelve months. Must always hope for the new year.

The record of the new year (1879) begins with the usual aspirations:—

"May every minute of this year be improved by me! This is too much to hope, but not too much to pray for. And I determine this year to pass no day without actual prayer, the want of which I have felt during the year just past. Busy all day, writing, washing handkerchiefs, and reading Herodotus."

On January 2, she "visited Blind School with General Stone — Osny Effendi, Principal. Many trades and handicrafts — straw matting, boys — boys and girls weaving at hand loom — girls spinning wool and flax, crochet and knitting — a lesson in geography. Turning lathe — bought a cup of rhinoceros horn."

On January 4 she is "sad to leave Egypt — dear beautiful country!"

"Jerusalem, January 5. I write in view of the Mount of Olives, which glows in the softest sunset light, the pale moon showing high in the sky. Christ has been here — here — has looked with his bodily eyes on this fair prospect. The thought ought to be overpowering — is inconceivable."

"January 9. In the saddle by half past eight in the morning. Rode two hours, to Bethlehem. Convent — Catholic. Children at the school. Boy with a fine head, Abib. In the afternoon mounted again and rode in sight of the Dead Sea. Mountains inexpressibly desolate and grand. Route very rough, and in some places rather dangerous... Grotto of the Nativity — place of the birth — manger where the little Christ was laid. Tomb of St. Jerome. Tombs of two ladies who were friends of the Saint. Later the plains of Boaz, which also [is] that where the shepherds heard the angels. Encamped at Marsaba. Greek convent near by receives men only. An old monk brought some of the handiwork of the brethren for sale. I bought a stamp for flat cakes, curiously cut in wood. We dined luxuriously, having a saloon tent and an excellent cook.... Good beds, but I lay awake a good deal with visions of death from the morrow's ride."

"January 10. [In camp in the desert near Jericho.] 'Shoo-fly'11 waked us at half past five banging on a tin pan and singing 'Shoo-fly.' We rose at once and I felt my terrors subside. Felt that only prayer and trust in God could carry me through. We were in the saddle by seven o'clock and began our perilous crossing of the hills which lead to the Dead Sea. Scenery inexpressibly grand and desolate. Some frightful bits of way — narrow bridle paths up and down very steep places, in one place a very narrow ridge to cross, with precipices on either side. I prayed constantly and so felt uplifted from the abjectness of animal fear. After a while we began to have glimpses of the Dead Sea, which is beautifully situated, shut in by high hills, quite blue in color. After much mental suffering and bodily fatigue on my part we arrived at the shores of the sea. Here we rested for half an hour, and I lay stretched on the sands which were very clean and warm! Remounted and rode to Jordan. Here, I had to be assisted by two men [they lifted her bodily out of the saddle and laid her on the ground] and lay on my shawl, eating my luncheon in this attitude. Fell asleep here. Could not stop long enough to touch the water. We rested in the shade of a clump of bushes, near the place where the baptism of Christ is supposed to have taken place. Our cans were filled with water from this sacred stream, and I picked up a little bit of hollow reed, the only souvenir I could find. Remounted and rode to Jericho. Near the banks of the Jordan we met a storm of locusts, four-winged creatures which annoyed our horses and flew in our faces. John the Baptist probably ate such creatures. Afternoon ride much better as to safety, but very fatiguing. Reached Jericho just after sunset, a beautiful camping-ground. After dinner, a Bedouin dance, very strange and fierce. Men and women stood in a semicircle, lighted by a fire of dry thorns. They clapped their hands and sang, or rather murmured, in a rhythm which changed from time to time. A chief danced before them, very gracefully, threatening them with his sword, with which he played very skilfully. They sometimes went on their knees as if imploring him to spare them. He came twice to our tent and waved the sword close to our heads, saying, 'Taih backsheesh.' The dance was like an Indian war-dance — the chief made a noise just like the war-whoop of our Indians. The dance lasted half an hour. The chief got his backsheesh and the whole troop departed. Lay down and rested in peace, knowing that the dangerous part of our journey was over."

"In Camp in the Desert. January 11. In the saddle by half past seven. Rode round the site of ancient Jericho, of which nothing remains but some portions of the king's highway. Ruins of a caravanserai, which is said to be the inn where the good Samaritan lodged his patient. Stopped for rest and luncheon, at Beth — and proceeded to Bethany, where we visited the tomb of Lazarus. I did not go in — then rode round the Mount of Olives and round the walls of Jerusalem, arriving at half past three in the afternoon. I became very stiff in my knees, could hardly be mounted on my horse, and suffered much pain from my knee and abrasions of the skin caused by the saddle. Did not get down at the tomb of Lazarus because I could not have descended the steps which led to it, and could not have got on my horse again. When we reached our hotel, I could not step without help, and my strength was quite exhausted. I say to all tourists, avoid Cook's dreadful hurry, and to all women, avoid Marsaba! This last day, we often met little troops of Bedouins travelling on donkeys — sometimes carrying with them their cattle and household goods. I saw a beautiful white and black lamb carried on a donkey. Met three Bedouin horsemen with long spears. One of these stretched his spear across the way almost touching my face, for a joke."

"Jerusalem. Sunday, January 12. English service. Communion, interesting here where the rite was instituted. I was very thankful for this interesting opportunity."

"January 15. Mission hospital and schools in the morning. Also Saladin's horse. Wailing place of the Jews and some ancient synagogues. In the afternoon walked to Gethsemane and ascended the Mount of Olives. In the first-named place, sang one verse of our hymn, 'Go to dark Gethsemane.' Got some flowers and olive leaves...."

After Jerusalem came Jaffa, where she delivered an address to a "circle" at a private house. She says:—

"In Jaffa of the Crusaders, Joppa of Peter and Paul, I find an American Mission School, kept by a worthy lady from Rhode Island. Prominent among its points of discipline is the clean-washed face, which is so enthroned in the prejudices of Western civilization. One of her scholars, a youth of unusual intelligence, finding himself clean, observes himself to be in strong contrast with his mother's hovel, in which filth is just kept clear of fever point. 'Why this dirt?' quoth he; 'that which has made me clean will cleanse this also.' So without more ado, the process of scrubbing is applied to the floor, without regard to the danger of so great a novelty. This simple fact has its own significance, for if the innovation of soap and water can find its way to a Jaffa hut, where can the ancient, respectable, conservative dirt-devil feel himself secure?"

Apropos of mission work (in which she was a firm believer), she loved to tell how one day in Jerusalem she was surrounded by a mob of beggars, unwashed and unsavory, clamoring for money, till she was wellnigh bewildered. Suddenly there appeared a beautiful youth in spotless white, who scattered the mob, took her horse's bridle, and in good English offered to lead her to her hotel. It was as if an angel had stepped into the narrow street.

"Who are you, dear youth?" she cried.

"I am a Christian!" was the reply.

In parting she says, "Farewell, Holy Land! Thank God that I have seen and felt it! All good come to it!"

From Palestine the way led to Cyprus ("the town very muddy and bare of all interest") and Smyrna, thence to Constantinople. Here she visited Robert College with great delight. Returning, she saw the "Sultan going to Friday's prayers. A melancholy, frightened-looking man, pale, with a large, face-absorbing nose...."

"February 3. Early at Piræus. Kalopothakis12 met us there, coming on board.... To Athens by carriage. Acropolis as beautiful as ever. It looks small after the Egyptian temples, and of course more modern — still very impressive...."

Athens, with its welcoming faces of friends, seemed almost homelike after the Eastern journeyings. The Journal tells of sight-seeing for the benefit of the younger traveller, and of other things beside.

"Called on the Grande Maîtresse at the Palace in order to have cards for the ball. Saw the Schliemann relics from Mycenæ, and the wonderful marbles gathered in the Museum. Have been writing something about these. To ball at the palace in my usual sober rig, black velvet and so forth. Queen very gracious to us.... Home by three in the morning."

"February 12. At ten in the morning came a committee of Cretan officers of the late insurrection, presenting a letter through Mr. Rainieri, himself a Cretan, expressing the gratitude of the Cretans to dear Papa for his efforts in their behalf.... Mr. Rainieri made a suitable address in French — to which I replied in the same tongue. Coffee and cordial were served. The occasion was of great interest.... In the afternoon spoke at Mrs. Felton's of the Advancement of Women as promoted by association. An American dinner of perhaps forty, nearly all women, Greek, but understanding English. A good occasion. To party at Madame Schliemann's."

"February 15. Miserable with a cold. A confused day in which nothing seemed to go right. Kept losing sight of papers and other things. Felt as if God could not have made so bad a day — my day after all; I made it."

"February 18. To ball at the Palace. King took Maud out in the German."

"February 21. The day for eating the roast lamb with the Cretan chiefs. Went down to the Piræus warmly wrapped up.... Occasion most interesting. Much speech-making and toasting. I mentioned Felton."

"February 22. Dreadful day of departure. Packed steadily but with constant interruptions. The Cretans called upon me to present their photographs and take leave. Tried a poem, failed. Had black coffee — tried another — succeeded...."

"February 23. Sir Henry Layard, late English minister to the Porte, is on board. Talked Greek at dinner — beautiful evening — night as rough as it could well be. Little sleep for any of us. Glad to see that Lord Hartington has spoken in favor of the Greeks, censuring the English Government."

"February 26.... Sir Henry Layard and I tête-à-tête on deck, looking at the prospect — he coveting it, no doubt, for his rapacious country, I coveting it for liberty and true civilization."

The spring was spent in Italy. In May they came to London.

"May 29. Met Mr. William Speare.... He told me of his son's death, and of that of William Lloyd Garrison. Gallant old man, unique and enviable in reputation and character. Who, oh! who can take his place? 'Show us the Father.'"

The last weeks of the London visit were again too full for any adequate account of them to find its way into her letters or journals. She visited London once more in later years, but this was her last long stay. She never forgot the friends she made there, and it was one of the many day-dreams she enjoyed that she should return for another London season. Sometimes after reading the account of the gay doings chronicled in the London "World," which Edmund Yates sent her as long as he lived, she would cry out, "O! for a whiff of London!" or, "My dear, we must have another London season before I die!"

CHAPTER II

NEWPORT

1879-1882; aet. 60-63

A THOUGHT FOR WASHING DAY

|

The clothes-line is a Rosary Of household help and care; Each little saint the Mother loves Is represented there. And when across her garden plot She walks, with thoughtful heed. I should not wonder if she told Each garment for a bead. . . . . . . . A stranger passing, I salute The Household in its wear, And smile to think how near of kin Are love and toil and prayer. J. W. H. |

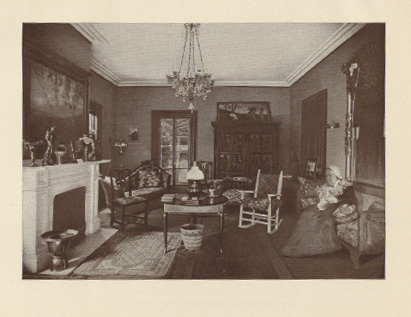

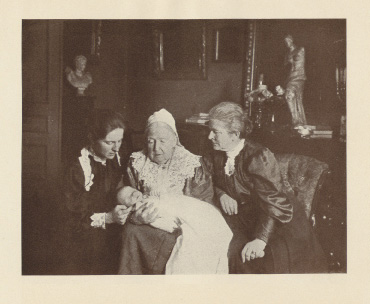

JULY, 1879, found our mother at home at Oak Glen, unpacking trunks and reading a book on the Talmud. She had met the three married daughters in Boston ("We talked incessantly for seven hours," says the Journal), and Florence and Maud accompanied her to Newport, where Florence had established her summer nursery. There were three Hall grandchildren now, and they became an important factor in the life at Oak Glen. All through the records of these summer days runs the patter of children's feet.

HALL FOUR GENERATIONS

MRS. HOWE, MRS. HALL, HENRY MARION HALL,

JULIA WARD HOWE HALL

From a photograph, 1903

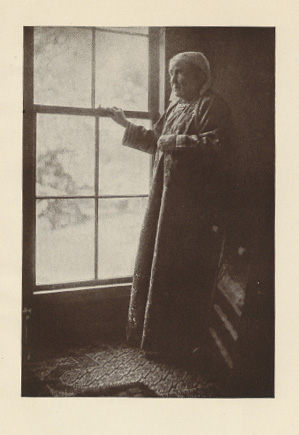

She kept only one corner of the house for her private use; a room with the north light which she then thought essential. This was at once bedroom and workroom: she never had a separate study or library. Here, as in Green Peace days, she worked quietly and steadily. Children and grandchildren might fill the house, might have everything it contained: she asked only for her "precious time." When she could not have an hour she took half an hour, a quarter, ten minutes. No fragment of time was too small for her to save, to invest in study or in work; and as her mind concentrated instantly on the subject in hand, no such fragment was wasted. The rule of mind over body was relentless: sick or well, she must finish her stint before the day closed.

This summer of 1879 was a happy one. After the feverish months of travel and pleasure, her delight in the soft Newport climate was deeper than ever. She always felt the change from the air of the mainland to that of the island, and never crossed the bridge from Tiverton to Bristol Ferry without an exclamation of pleasure. She used to say that the soft, cool air of Newport smoothed out the tired, tangled nerves "like a silver comb"!

"July 29. To my Club, where, better than any ovation, an affectionate greeting awaited me.... Thucydides is very difficult."

This was the Town and Country Club, for some years a great interest to her. In her "Reminiscences" she tells how in a summer of the late sixties or early seventies, when Bret Harte and Dr. J. G. Holland, Professors Lane and Goodwin of Harvard were spending the season at Newport: "A little band of us combined to improve the beautiful summer season by picnics, sailing parties, and household soirées, in all of which these brilliant literary lights took part. Helen Hunt and Kate Field were often of our company, and Colonel Higginson was always with us."

. . . . . . . .

Among the frolics of that summer was the mock Commencement, arranged by her and Professor Lane.

"I acted as President, Colonel Higginson as my aide; we both marched up the aisle in Oxford caps and gowns. I opened the proceedings by an address in Latin, Greek, and English; and when I turned to Colonel Higginson and called him 'fili mihi dilectissime,' he wickedly replied with three bows of such comic gravity that I almost gave way to unbecoming laughter. Not long before this he had published a paper on the Greek goddesses. I therefore assigned as his theme the problem, 'How to sacrifice an Irish bull to a Greek goddess.' Colonel George Waring, the well-known engineer, being at that time in charge of a valuable farm in the neighborhood, was invited to discuss 'Social small potatoes: how to enlarge their eyes.' An essay on rhinoscopy was given by Fanny Fern, the which I, chalk in hand, illustrated on the blackboard by the following equation:—

"Nose+nose+nose=proboscis.

Nose-nose-nose=snub.

"A class was called upon for recitations from Mother Goose in seven different languages. At the head of this Professor Goodwin honored us with a Greek version of the 'Man in the Moon.' A recent Harvard graduate, Dr. Gorham Bacon, recited the following, also of her composition:—

"'Heu iterum didulum,

Felis cum fidulum,

Vacca transiluit lunam,

Caniculus ridet,

Quum tale videt,

Et dish ambulavit cum spoonam.'

"The question being asked whether this last line was in strict accordance with grammar, the scholar gave the following rule: 'The conditions of grammar should always give way to the exigencies of rhyme.'

"The delicious fooling of that unique summer was never repeated. Out of it came, however, the more serious and permanent association known as the Town and Country Club of Newport. I felt the need of upholding the higher social ideals and of not leaving true culture unrepresented, even in a summer watering-place."

With the help and advice of Professor and Mrs. William B. Rogers, Colonel Higginson and Mr. Samuel Powell, a number of friends were called together in the early summer of 1874 and she laid before them the plan of the proposed club. After speaking of the growing predominance of the gay and fashionable element in Newport society, she said:—

"But some things can be done as well as others. Newport... has also treasures which are still unexplored....

"The milliner and the mantua-maker bring here their costly goods and tempt the eye with forms and colors. But the great artist, Nature, has here merchandise far more precious, whose value and beauty are understood by few of us. I remember once meeting a philosopher in a jeweller's shop. The master of the establishment exhibited to us his choicest wares, among others a costly diamond ornament. The philosopher [we think it was Emerson] said, 'A violet is more beautiful.' I cannot forget the disgust expressed in the jeweller's face at this remark."

She then outlined the course laid out by the "Friends in Council," lectures on astronomy, botany, natural history, all by eminent persons. They would not expect the Club to meet them on their own ground. They would come to that of their hearers, and would unfold to them what they were able to understand.

Accordingly, Weir Mitchell discoursed to them on the Poison of Serpents, John La Farge on the South Sea Islands, Alexander Agassiz on Deep-Sea Dredging and the Panama Canal; while Mark Twain and "Hans Breitmann" made merry, each in his own inimitable fashion.

The Town and Country Club had a long and happy career. No matter what heavy work she might have on hand for the summer, no sooner arrived at Newport than our mother called together her Governing Committee and planned out the season's meetings.

It may have been for this Club that she wrote her "Parlor Macbeth," an extravaganza in which she appeared as "the impersonation of the whole Macbeth family."

In the prologue she says:—

"As it is often said and supposed that a woman is at the bottom of all the mischief that is done under the sun, I appear and say that I am she, that woman, the female fate of the Macbeth family."

In the monologue that follows, Lady Macbeth fairly lives before the audience, and in amazing travesty relates the course of the drama.

She thus describes the visit of the weird sisters (the three Misses Macbeth) who have been asked to contribute some of "their excellent hell-broth and devilled articles" for her party.

"At 12 M., a rushing and bustling was heard, and down the kitchen chimney tumbled the three weird sisters, finding everything ready for their midnight operations.... 'That hussy of a Macbeth's wife leaves us nothing to work with,' cried one. 'She makes double trouble for us.' 'Double trouble, double trouble,' they all cried and groaned in chorus, and presently fell into a sort of trilogy of mingled prose and verse which was enough to drive one mad.

| Where hast thou been? Sticking pigs. And where hast thou? Why, curling wigs Fit for a shake in German jigs And hoo! carew! carew!' . . . . . . . . |

"'We must have Hecate now, can't do without her. Throw the beans over the broomstick and say boo!' And lo, Hecate comes, much like the others, only rather more so....

"Now they began to work in good earnest. And they had brought with them whole bottles of sunophon, and sozodont, and rypophagon, and hyperbolism and consternaculum, and a few others. And in the whole went. And one stirred the great pot over the fire, while the others danced around and sang —

| Black pepper and red, White pepper and grey, Tingle, tingle, tingle, tingle, Till it smarts all day.' |

"'Here's dyspepsia! Here's your racking headache of a morning. Here's podagra, and jaundice, and a few fits. And now it's done to a turn, and the weird sisters have done what they could for the family.'

"A rumbling and tumbling and foaming was now heard in the chimney — the bricks opened, and He-cat and She-cat and all the rest of them went up. And I knew that my supper would be first-rate."

The time came when some of the other officers of the Town and Country Club felt unable to keep the pace set by her. She would still press forward, but they hung back, feeling the burden of the advancing years which sat so lightly on her shoulders. The Club was disbanded; its fund of one thousand dollars, so honorably earned, was given to the Redwood Library, one of the old institutions of Newport.

The Town and Country Club was succeeded by the Papéterie, a smaller club of ladies only, more intimate in its character. The exchange of "paper novels" furnished its name and its raison d'être. The members were expected to describe the books taken home from the previous meeting. "What have you to tell us of the novel you have been reading?" the president would demand. Then followed a report, serious or comic, as the character of the volume or the mood of the meeting suggested. A series of abbreviated criticisms was made and a glossary prepared: for example, —

| B. P. — By the pound. M. A. S. — May amuse somebody. P. B. — Pot-boiler. F. W. B. — For waste-basket. U. I. — Uplifting influence. W. D. — Wholly delightful. U. T. — Utter trash." |

The officers consisted of the Glossarian, the Penologist, whose duty it was to invent penalties for delinquents, the Cor. Sec. and the Rec. Sec. (corresponding and recording secretaries) and the Archivist, who had charge of the archives. During its early years a novel was written by the Club, each member writing one chapter. It still exists, and part of the initiation of a new member consists in reading the manuscript. The "delicious fooling" that marked the first year of the Town and Country Club's existence was the animating spirit of the Papéterie. A friend christened it "Mrs. Howe's Vaudeville." Merrymaking was her safety-valve. Brain fag and nervous prostration were practically unknown to her. When she had worked to the point of exhaustion, she turned to play. Fun and frolic went along with labor and prayer; the power of combining these kept her steadily at her task till the end of her life. The last time she left her house, six days before her death, it was to preside at the Papéterie, where she was as usual the life of the meeting! The Club still lives, and, like the New England Woman's Club, seems still pervaded by her spirit.

The Clubs did not have all the fun. The Newport "Evening Express" of September 2, 1881, says: "Mrs. Julia Ward Howe has astonished Newport by her acting in 'False Colors.' But she always was a surprising woman."

Another newspaper says: "The interest of the Newport world has been divided this week between the amateur theatricals at the Casino and the lawn tennis tournament. Two representations of the comedy of 'False Colors' were given on Tuesday and Wednesday evenings.... The stars were undoubtedly Mrs. Julia Ward Howe and Mr. Peter Marié, who brought down the house by their brightness and originality.... Mr. Peter Marié gave a supper on the last night of the performance, during which he proposed the health of Mrs. Julia Ward Howe and the thanks of the company for her valuable assistance. Mrs. Howe's reply was very bright and apt, and her playful warnings of the dangers of sailing under false colors were fully appreciated."

It is remembered that of all the gay company she was the only one who was letter-perfect in her part.

To return to 1879. She preached many times this summer in and around Newport.

"Sunday, September 28. Hard at work. Could not look at my sermon until this day. Corrected my reply to Parkman.13 Had a very large audience for the place — all seats full and benches put in."

"My sermon at the Unitarian Church in Newport. A most unexpected crowd to hear me."

"September 29. Busy with preparing the dialogue in 'Alice in Wonderland' for the Town and Country Club occasion...."

Many entries begin with "hard at work," or "very busy all day."

This summer was made delightful by a visit from her sister Louisa, with her husband14 and daughter. Music formed a large part of the summer's pleasure. The Journal tells of a visit from Timothée Adamowski which was greatly enjoyed.

"October 11. Much delightful music. Adamowski has made a pleasant impression upon all of us."

"October12, Sunday. Sorry to say we made music all day. Looked hard for Uncle Sam, who came not."

"October 13. Our delightful matinée. Adamowski and Daisy played finely, he making a great sensation. I had the pleasure of accompanying Adamowski in a Nocturne of Chopin's for violin and piano. All went well. Our pleasure and fatigue were both great. The house looked charming."

In the autumn came a lecture tour, designed to recoup the heavy expenses of the Eastern trip. Never skilful in matters of money-making, this tour was undertaken with less preparation than the modern lecturer could well imagine. She corresponded with one and another Unitarian clergyman and arranged her lectures largely through them. Though she did not bring back so much money as many less popular speakers, she was, after all, her own mistress, and was not rushed through the country like a letter by ambitious managers.

The Journal gives some glimpses of this trip.

"Twenty minutes to dress, sup, and get to the hall. Swallowed a cup of tea and nibbled a biscuit as I dressed myself."

"Found the miserablest railroad hotel, where I waited all day for trunk, in distress!... Had to lecture without either dress or manuscript. Mrs. Blank hastily arrayed me in her black silk, and I had fortunately a few notes."

She never forgot this lesson, and in all the thirty-odd years of speaking and lecturing that remained, made it an invariable rule to travel with her lecture and her cap and laces in her handbag. As she grew older, the satchel grew lighter. She disliked all personal service, and always wanted to carry her hand-luggage herself. The light palm-leaf knapsack she brought from Santo Domingo was at the end replaced by a net, the lightest thing she could find.

The Unitarian Church in Newport was second in her heart only to the Church of the Disciples. The Reverend Charles T. Brooks, the pastor, was her dear friend. In the spring of 1880 a Channing memorial celebration was held in Newport, for which she wrote a poem. She sat on the platform near Mr. Emerson, heard Dr. Bellows's discourse on Channing, "which was exhaustive, and as it lasted two hours, exhausting." The exercises, W. H. Channing's eulogium, etc., etc., lasted through the day and evening, and in the intervals between addresses she was "still retouching" her poem, which came last of all. "A great day!" says the Journal.

"July 23. Very busy all day. Rainy weather. In the evening I had a mock meeting, with burlesque papers, etc. I lectured on Ism-Is-not-m, on Asm-spasm-plasm."

"July 24. Working hard, as usual. Marionettes at home in the evening. Laura had written the text. Maud was Julius Caesar; Flossy, Cassius; Daisy, Brutus."

"July 28. Read my lecture on 'Modern Society' in the Hillside Chapel at Concord.... The comments of Messrs. Alcott and W. H. Channing were quite enough to turn a sober head."

"To the poorhouse and to Jacob Chase's with Joseph Coggeshall. Old Elsteth, whom I remember these many years, died a few weeks ago. One of the pauper women who has been there a long time told me that Elsteth cried out that she was going to Heaven, and that she gave her, as a last gift, a red handkerchief. Mrs. Anna Brown, whom I saw last year, died recently. Her relatives are people in good position and ought to have provided for her in her declining years. They came, in force, to her funeral and had a very nice coffin for her. Took her body away for burial. Such meanness needs no comment.

"Jacob was glad to see me. Asked after Maud and doubted whether she was as handsome as I was when he first saw me (thirty or more years ago). His wife said to me in those days: 'Jacob thinks thee's the only good-looking woman in these parts.' She was herself a handsome woman and a very sweet one. I wish I had known I was so good-looking."

Of the writing of letters there was no end. Correspondence was rather a burden than a delight to her; yet, when all the "duty letters" were written, she loved to take a fresh sheet and frolic with some one of her absent children. Laura, being the furthest removed, received perhaps more than her share of these letters; yet, as will appear from them, she never had enough.

To Laura

OAK GLEN, October 10, 1880.

DEAREST, DEAREST L. E. R., —